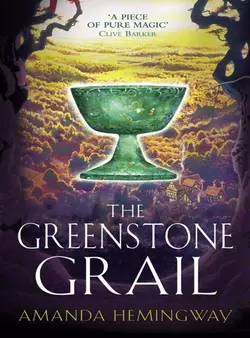

The Greenstone Grail: The Sangreal Trilogy One

Jan Siegel

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 152.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The first book in a brand new trilogy from the author of Prospero’s Children.Bartlemy Goodman, is one of the Gifted. An albino of Greek parentage, he was born in Byzantium amidst the decline of the Roman Empire. He now resides at Thornyhill house, England, with his dog, Hoover.One warm evening, a young homeless woman holding a baby turns up on Bartlemy′s doorstep, and sensing destiny at work, he lets them stay. Annie and her son Nathan thrive in the small community of Thornyhill, but when more strangers arrive in the village, sinister happenings begin to occur.