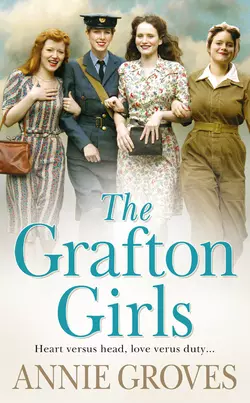

The Grafton Girls

Annie Groves

The new Liverpool-based World War Two saga from the author of Goodnight Sweetheart is a tale of four very different young women thrown together by war. A unique bond is formed as the hostilities take their toll on Britain.When Diane Wilson leaves Cambridge for Liverpool, destined for Derby House and war work as a teleprint operator, she is intent on mending her broken heart. But will hundreds of miles ease the pain of her betrayal?From the moment she first lays eyes on Myra Stone in the Wavertree terrace she is billeted to, Diane senses she's bad news. But does Myra's bitterness and caustic wit belie a secret heartache?Ruthie starts work at the munitions factory, enduring terrible conditions in order to put food on the table for herself and her widowed mother. But Ruthie is befriended by lively and vivacious Jess Hunt who injects colour and fun into the drab surroundings.All four women are brought together at The Grafton, the local dance hall favoured by American GIs as well as the local girls. In this heady, uncertain time, infatuation and passion blossom. But has each girl found true love – or true trouble?

ANNIE GROVES

The Grafton Girls

COPYRIGHT (#u9da74828-f8af-5d5a-bbec-37a31e0e7ac2)

This novel is entirely a work of fiction.

The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

This paperback edition 2007

1

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2007

Copyright © Annie Groves 2007

Annie Groves asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Set in Sabon by Palimpsest Book Production Limited, Grangemouth, Stirlingshire

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Source ISBN-13: 9780007209675

Ebook Edition © September 2008 ISBN:9780007279517

Version: 2017-09-12

Epigraph

To the readers for their generous reception to the first of my World War Two books. I hope they will enjoy this one as much.

Annie Groves

CONTENTS

TITLE PAGE (#ud751dd3c-76ca-5dc3-9b7a-9cc193715d24)

COPYRIGHT

EPIGRAPH

PART ONE

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

PART TWO

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

NINETEEN

TWENTY

PART THREE

TWENTY-ONE

TWENTY-TWO

TWENTY-THREE

TWENTY-FOUR

TWENTY-FIVE

TWENTY-SIX

TWENTY-SEVEN

TWENTY-EIGHT

TWENTY-NINE

THIRTY

THIRTY-ONE

EPILOGUE

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

PART ONE

ONE

‘My station’s coming up next, and then it’ll be Lime Street, luv, tek it from me. Done this ruddy train journey that many times, I have, since this bloomin’ war began, I can tell the stops practically in me sleep. That is, of course, if a person could manage to get any sleep with the trains being that full and noisy. Not that I’m complaining, like, not about the overcrowding nor about all the place names being teken down from the stations so as to confuse any of Hitler’s spies wot manage to land. Aye, and if I were your age, I’d be in uniform too. WAAF isn’t it?’ Diane Wilson’s new-found friend said knowingly, referring to the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, studying Diane’s airforce-blue-clad frame admiringly.

‘That’s right.’ Diane smiled politely enough to be pleasant but not so warmly that she would be encouraging the woman to ask her too many questions.

‘A right ’andsome lot them fly boys are. By, if I had me time again…’ the older woman chuckled.

Now it was harder for Diane to force a responsive smile. Automatically, and despite the fact that she was wearing gloves, she placed her right hand over the bare place on her ring finger. The pain she thought she had under control could sneak up on her to catch her unawares and stab her with such agonising sharpness. She ought to be over it by now. After all, it had been three months. Three months, two days and ten hours, an inner voice tormented her. Resolutely Diane ignored it. She had known other girls, any number of them, who had been stationed with her at Upwood, Cambridgeshire, who had gone from being desperately in love with one chap to clinging happily to the arm of another when they had lost him. So there was no reason why she shouldn’t be doing the same. Only she wouldn’t be clinging – not to any man – not ever again. There was no danger of her repeating that mistake. Sometimes, when she was at her lowest ebb, the horrid thought wouldn’t go away, the thought that it might have been easier to accept things if Kit had been killed instead of…

‘You’ll be heading for that Derby House, then, like as not?’ the woman leaned towards her to whisper, interrupting her reverie. ‘Saw Mr Churchill himself standing outside of it one morning, I did. Smiled at me, an’ all. Hitler might have ’is ruddy SS but just so long as we’ve got our Mr Churchill we’ll be sound, mark my words,’ she added stoutly.

She was a good sort, Diane recognised, a bit shabbily dressed, but then who wasn’t these days, with the war in its third year and new clothes only available if one had enough coupons with which to purchase them. Luckily she had joined the WAAF before clothing coupons had come in, and so she had not had to part with any of her own precious coupons in exchange for her obligatory WAAF uniform of black lace-up shoes, grey lisle stockings, which none of the girls wore during the summer months if they could help it, a skirt, a tunic, a peaked cap – which the girls loved as much as they hated the lisle stockings –an overcoat, which came in jolly useful in the winter, and even regulation underwear, with its horrid bubble-gum-pink ‘foundation garments’, although none of the girls wore these either if they could get away with wearing their own underwear instead.

More seriously, the whole country was now feeling the effect of the food rationing that had been brought in at the beginning of the war, but if Hitler had hoped to destroy the fighting spirit of the British by attempting to sink the ships struggling across the Atlantic to bring in the supplies on which the country depended, he had omitted to take into account the sturdiness of the nation’s spirit, Diane recognised proudly.

Her recent request for a transfer was responsible for Diane’s presence on this train to Liverpool and her new post at Derby House, the headquarters of the combined forces protecting the convoys coming into the port. Her life in Liverpool would be very different from that in Cambridgeshire, she knew. Several of the pals she had been leaving behind had expressed doubts about the wisdom of what she was doing.

‘Liverpool!’ more than one of them had exclaimed, pulling a face. ‘You wouldn’t catch me wanting to transfer up there. Not for anything.’

Diane had affected not to notice the sharp nudge another of her friends had given the speaker, knowing that the warning was kindly meant and intended to protect her feelings. Her broken heart.

She could feel the burning threat of tears at the back of her eyes, and was thankful for the diversion of the sudden hiss of the train’s brakes and the noise of escaping steam, plus the bustle of her travelling companion getting ready to leave the train.

‘Well, here’s my station.’

Diane forced herself to return the woman’s smile.

‘Good luck, lass,’ the older woman said, giving Diane a grateful look as she helped her out of the compartment with her bags. ‘You’ll like Liverpool once you get to know it. Of course, it’s not the place it was, not since that ruddy May bombing back in ’forty-one. A whole week of it, we had, and it ripped the heart out of the city, and no mistake. There was hardly a family in the city that didn’t lose someone, and there were thousands evacuated who didn’t come back. But it takes more than a few bombs to knock the stuffing out of Liverpudlians, as you’ll soon find out.’

The bright summer sunshine was surely enough of an excuse for her to blink, Diane reassured herself as the train pulled out of the station. And if she was also blinking away those threatening tears then who was to know but her? No one here knew anything about her or her situation. That alone was enough to make her glad that the transfer she had begged for had brought her here.

‘HQ Western Approaches won’t be what you’re used to here, Wilson,’ she had been warned when she had been called to the office to receive her new orders from her commanding officer.

‘But I’ll still be working as a teleprinter operator, won’t I, ma’am?’ she had asked, uncertainly.

‘Well, as to that, I dare say that yes, you will. But Derby House is a joint effort run principally by the Senior Service,’ she told Diane, referring to the British Navy, ‘unlike here, where it’s all RAF. It will be part of your duty as a WAAF to make sure that you create the right impression on those you’ll be working with.’ When her CO had added, straight-faced, ‘The Senior Service takes a pretty dim view of flighty behaviour,’ Diane hadn’t known whether or not she was cracking a joke.

‘The CO joke?’ one of her pals had scoffed when she had related the incident to her. ‘That’ll be the day!’

Diane hadn’t really needed her CO’s warning. Everyone in uniform knew about the rivalries between the various services, and that the Senior Service in particular tended to look down somewhat on the upstart RAF.

She could practically hear Kit’s voice now -strong and filled with good humour as he laughed, ‘The trouble with those Senior Service lot is that they’re jealous of our success.’

‘You mean because of the Battle of Britain?’ Diane had asked, thinking he had meant that the navy men envied the victory the RAF had had over the Luftwaffe in the summer of 1940, when men like Kit had driven back the incoming German fighters.

‘No,’ she remembered Kit had told her, his eyes – fighter pilot’s far-seeing eyes – crinkling up at the corners with amusement as he had leaned forward and told her boldly, ‘I meant because of our success with the fairer sex.’

She had pretended to be dismissive, tossing her head as they stood together at the small bar of the packed Cambridgeshire pub on that breathlessly hot summer night, but when a careless airman, overeager to get to the bar before the beer ran out, had accidentally bumped into her, she hadn’t complained when Kit had made a grab for her waist. ‘To protect you,’ he had assured her guilelessly, but he hadn’t been in any hurry to release her, and the truth was that by that stage she had been too entranced by him to want him to. With Kit, over six foot tall, broad-shouldered, with a shock of thick wavy dark hair, and the kind of good looks and easy charm that had already got him a nine out of ten rating in the WAAF canteen, there was barely a girl Diane knew who wouldn’t have fallen for his charms.

But there had been another side to him, or so she had believed. A side that…

The sudden jerk of the train’s brakes brought her back to the present. Already the corridor outside her carriage was packed with passengers wanting to get off. Diane reached up to the overhead luggage rack to remove her kitbag, ready to join the stream of people disembarking at Lime Street.

So this was Liverpool. The voices she could hear all around her certainly had very different accents from those in Cambridgeshire, although the Liverpool accent wasn’t the only one swelling the noise in the busy station, and Diane’s eyes widened a little when she saw – and heard – how many Americans there were clustered around in large groups.

They would, of course, be the ‘Yanks’ from the American base at Burtonwood, which her fellow traveller had mentioned. American bases were being established in Lincolnshire, and at Bomber Command, in High Wycombe, and there had been American personnel at the Cambridgeshire base as well. Diane had heard from some of the other girls about the attractions of the American male and the American PX – as the stores on the newly established American supply bases were named -both generous providers of much that was unavailable or rationed, including chocolate and stockings.

The station platforms were busy with men in uniform, with the distinctively dressed women of the Women’s Voluntary Service also very much in evidence with their tea urns. Diane would not have said no to a cuppa herself, but it had already gone five in the evening and she still had to find her way to her billet near Wavertree.

One of the friendly WVS women was happy to explain to Diane how to get to her billet on Chestnut Close, which was in what she described approvingly as ‘a respectable part of the city’.

‘It’s a fair walk, but you could take the bus.’

‘No, I’d prefer the walk,’ Diane assured her.

The summer sunshine had enough warmth in it to make her walk a pleasant one, and to allow her to pause to stare in shocked compassion at the blitzed and bombed-out centre of the city. She could see huge gaps where it looked as though whole streets had disappeared, and smaller ones, where only a single house had gone, leaving the rest of the street intact.

The city was very different from the pretty Hertfordshire village where she had grown up, Diane acknowledged. Her parents were far from well off, but their semi was one of several on a quiet leafy lane opposite the village green and duck pond. Diane had grown up knowing virtually everyone else who lived in the village. She couldn’t help contrasting the pretty comfortable calm of her home village with the devastation of this powerful northern port city. Her parents had been proud but anxious when she had announced her intention of doing her bit and joining up, and they had been even more anxious when she had told them that she was seeing an airman, insisting that she took him home with her so that they could meet him. Although at first they had been cool towards him, by the time Diane and Kit’s forty-eight-hour pass was up, Kit had completely charmed them. Diane had been so thrilled and proud, both of him and her parents. Of course, the minute her mother had discovered that he was virtually an orphan, having lost his mother shortly after his birth, she had taken to fussing over him. They had laughed about it together later, Kit teasing Diane that once they were married she would never be able to run home to her mother because she would always take his side. She had laughed too, telling him with the assurance that falling in love brought that she would never ever want to run anywhere other than to him.

She had been so deliriously happy, living in a world coloured by her hopes and dreams for the future, even if her heart had been in her mouth during every mission Kit flew, her fear always that he might not make it back. Too happy, she knew now. And her fear should not just have been for Kit’s survival but for the survival of their love.

She had been so busy with her own thoughts whilst she was walking that she hadn’t really observed very much of her surroundings, and it came as a surprise when she realised that she must have passed the hospital she had been told to look out for and that she could now see the Picton Clock landmark she had been warned meant that she had gone too far and missed her turning.

An elderly woman, obviously having noticed her looking around, came over to her.

‘Lost your way, have you?’ she enquired.

‘I’ve been billeted to Chestnut Close,’ Diane explained, ‘but I think I’ve missed my turning.’

‘Well, as to that,’ the other woman sniffed, ‘you have, yes. This is Wavertree, not Edge Hill.’ The way she stressed what she obviously considered to be the superiority of ‘Wavertree’ would normally have made Diane smile. A similarly petty type of snobbery existed in Melham on the Green, the village where she had grown up, with one end of it being considered ‘better’ than the other. Kit had enjoyed teasing her about her mother’s pride in the fact that their well-cared-for semi was just over the invisible border that separated the ‘better’ end of the village from the ‘other’ end. ‘And, of course, we aren’t supposed to give out directions to strangers,’ the elderly lady added pompously.

‘No, indeed,’ Diane responded with suitable gravity. ‘Actually, I do have the directions, but I’ve wandered off track. I believe that I should have turned off left for Chestnut Close before I got here.’

‘There’s some folks that live there that like to claim that it’s in Wavertree, on account of it being on the border, but even if they are right, the better part of Wavertree is further up the road, past the tennis club and that. I expect you play tennis, do you? I used to play myself when I was younger.’

Diane made her excuses as tactfully as she could. The older woman’s question had brought a fresh wave of painful memories. The previous summer she and Kit had just managed to snatch the mixed doubles trophy from the previous year’s winners at the Cambridgeshire courts where they and other members of the RAF squadrons based locally played.

It had been at the tennis club, on a warm September night just after the Battle of Britain, not yet two years ago, that Kit had proposed to her.

If they had got married straight away then, instead of deciding to wait, would things have been any different?

It didn’t take Diane long to retrace her steps and find the turning into Chestnut Close, which turned out to be a neat collection of small semidetached homes and terraces of four interlinked red-brick houses, with low red-brick front garden walls and privet hedges.

Number 24 was about a quarter of the way down Chestnut Close, and Diane suspected that she saw several sets of net curtains twitching as she walked up its tidy gravel path.

The front door was opened the moment she knocked.

‘Come in, dear,’ she was instructed by the small, plump woman in her fifties who greeted her, whom Diane assumed to be her landlady. ‘I’ve bin expecting you. Tired, are you, and parched too, I’m sure? I’ll put the kettle on and then I’ll take you up and show you the room. You’ll be sharing, did they tell you that? Another young lady who’s working at Derby House. I told them when they asked me if I’d have some lodgers that with me being a widow and liking things just so, I’d only take young ladies. Not that some of them I’ve had have been what I’d call “ladies”, but then I can tell that you’re a decent sort. I’m Mrs Lawson, by the way. It’s a good-size room, the largest in the house. It was me and my Herbert’s room but seein’ as I’m on me own now I moved out of it, like, and I got rid of the double, had a pair of single beds put in – there was that many young couples wanting to have it, what with the furniture shortage an’ all, and there’s much more space in the back room now with only a single in it. It’s funny, isn’t it, some folks don’t like sleeping in a single after they’ve shared, but me, I don’t mind at all. I like me own space, you see, and men and marriage -well, they aren’t allus what they’re made out to be, take it from me. It’s this way,’ she continued without pausing for breath, as she started up the stairs, leaving Diane to follow her.

‘Now I’m very fussy about the state of me bathroom – I won’t have no makeup nor any of that fake leg stuff all over everything. Baths are once a week, unless you want to pay for extra. You’ll get your breakfast, and a meal before you go out when you do your night shift. But there’s to be no food taken upstairs to your room. And no followers neither,’ she added firmly. ‘I won’t have no truck with any of that kind of goings-on.’

They had reached the landing and Diane reflected ruefully that beneath Mrs Lawson’s soft outer plumpness lay a core of pure steel.

‘The lady wot you’ll be sharing with is married. Only bin here a couple of weeks herself, she has.’

‘This is the room.’ She gave a small knock on the door and called out, ‘It’s only me, Mrs Stone, duck, bringing up the new lady.’

Diane heard the sound of the door lock being pulled back, and then the door opened.

‘I’ll leave you two to get to know one another whilst I make you both a cuppa,’ Mrs Lawson announced.

‘Not for me, thanks, Mrs L. I’ve got to go soon,’ said the room’s occupant.

‘Right you are, duck,’ said the landlady, leaving Diane and the girl now seated on one of the room’s two narrow single beds to study one another surreptitiously in the slightly awkward silence that followed her exit.

‘I’m Diane – Di,’ Diane introduced herself.

‘Myra Stone,’ the other girl responded.

Diane had never seen a more stunningly beautiful nor sensuously voluptuous-looking young woman. She had the kind of looks that would have turned men’s heads in the street. She had glossy brown curls, and brown eyes that should have looked warm but which instead held an expression of cynical brittleness that both shocked Diane and made her feel wary. Somehow that voluptuous body and those cold eyes just did not match up with one another.

‘You’d better come in and shut the door. I’ve already bagsied this bed,’ Myra told her, indicating the better positioned of the two beds. ‘And I’d better warn you now that there’s next to no wardrobe or drawer space left.’

‘I dare say I’ll be able to manage,’ Diane responded lightly. ‘It can’t be worse than we had at camp. I haven’t lived out before.’

‘Well, you won’t have to bother about curfews or anything like that,’ Myra told her, ‘and the social life’s pretty good up here, especially now that the Yanks have arrived. Have you dated any Yanks yet?’

Diane stiffened. Already a certain amount of competitive hostility had developed between the RAF flyers and the newly arrived Americans. The readiness of some girls to accept ‘dates’, as the Americans called them, from the newcomers had resulted in them being branded as ‘disloyal’, and there had even been incidents of outright hostility, with them being accused of favouring the Americans because of the luxuries they could provide.

‘You’ll be working at Derby House, I expect?’

‘Yes,’ Diane agreed, as she removed her gloves and her jacket, and then lifted her hand to make sure that her blonde hair was still smoothed neatly into its chignon. Her fingers were slender and fine-boned, her wrist blue-veined under creamy skin. Her colouring was more Nordic than English rose, and her father had always teased her that her blonde hair and blue eyes, together with her height and slender frame, were a throwback to some Viking ancestor on her mother’s side of the family. Diane had learned young that her looks made her stand out from the crowd and that sometimes other girls could be wary of her because of them. That in turn had led to her developing an initial defensive calm coolness of manner with people. ‘My Ice Princess’, Kit had called her. Diane knew that she did tend to hide her own shyness away behind a protective front with new people.

‘So what happened to him, then?’

Myra’s question caught her off guard, causing the colour to rise in her face. ‘What happened to who?’ she responded as soon as she had recovered her equilibrium.

‘The chap who gave you the ring you’ve taken off.’ Myra gestured towards Diane’s left hand and then waggled her own ring finger. ‘See, I’ve got the same telltale white mark. I always check out other girls’ ring fingers. It takes one to know one,’ she told Diane drily. ‘Husbands, eh…’

‘We weren’t married, only engaged,’ Diane told her sharply.

‘Lucky you,’ Myra drawled. ‘I just wish I could say the same. But, more fool me, I went and married mine, and you know what they say about marrying in haste? Well, take it from me it’s true.’ She paused and gave Diane a speculative look before demanding, ‘So what happened to him, then? Bought it, did he?’

Diane could hardly believe her ears. For sheer callousness Myra’s question couldn’t be beaten. If Kit had lost his life – or ‘bought it’, as Myra had so casually enquired – Diane knew she would have been overwhelmed with grief by Myra’s nosy probing. She looked angrily across and saw that Myra was waiting almost eagerly for her response. Diane had met women like Myra before, women who were so unhappy in their own lives that they fed off the misery of others. She had always taken care to avoid such types and her heart sank at the realisation that being billeted here meant she was not going to be able to now. Well, she might have to share a room with her, but she certainly wasn’t going to play along and give Myra the satisfaction of seeing her upset, Diane decided firmly.

Lifting her head she told her crisply, ‘No, actually, if anything, it was our relationship that “bought it”.’ Diane forced herself to give a small dismissive shrug. ‘These things happen in wartime.’ Not for the world was she going to allow Myra to guess at the pain that lay beneath her casual dismissal of her broken engagement.

Even so, she was surprised when Myra immediately pounced on her words and told her openly, ‘Don’t they just. Like I said, you want to be thankful that all you did was get engaged. An engagement’s easily got out of, not like marriage. I can’t believe now that I was such a fool. If I had my time over again, I’d know better. Three years I’ve been married, and I knew within three months I’d made a mistake. I told him last time he was on leave that I wanted to end it, but he wouldn’t agree, so it looks like I’m going to have to hope that the war does the job for me.’

Diane couldn’t conceal her shocked revulsion.

‘You needn’t look at me like that,’ Myra told her sharply. ‘You don’t know what it’s like. Worst mistake I’ve ever made – not that it doesn’t come in handy sometimes, like when a chap at a dance gets a bit too forward. I just tell him I’m married and that my hubby is serving abroad, and nine times out of ten that’s enough to make ’em back off. Not of course that I always want to say “no”. Not now we’ve got all these Yanks over here. Really know how to treat a girl, they do, not like our own lads. You should see them – tall, they are, and that handsome in those uniforms of theirs…What’s wrong?’ she demanded, obviously sensing Diane’s disapproval.

‘Nothing,’ Diane lied, and then admitted, ‘Well, if you must know, I think it’s a pretty poor thing for you to be praising American men. It seems disloyal to our own boys.’

‘Oh, I see, you’re one of them, are you? Have you ever met any Yanks?’ she challenged Diane.

‘As a matter of fact, yes I have,’ Diane told her coolly. It didn’t do to give away information, even to a colleague in uniform, so she wasn’t going to tell Myra that she had been based in Cambridgeshire and so had had any amount of opportunity to observe ‘Yanks’.

‘Oh, hoity-toity now, is it!’ Myra mocked her. ‘Well, you can do as you please because I certainly intend to, and when it comes to a handsome chap wanting to take me dancing and offering me nylons and other little treats, I know where my loyalty is going to lie, and that is to meself! You can disapprove all you like,’ she added determinedly. ‘I’ve had enough of this ruddy war, and I want to have a bit of a good time whilst I still can. If you had any sense you’d do the same. After all, what have you got to lose? Anyway, I’m going now. I’m on duty at eight.’ She pulled on her jacket and crammed her cap down onto her curls, then headed for the door.

Diane watched her go, relieved but feeling sorry that they had not got off to a better start. How many weeks of Myra’s carping could she stand?

When she reached the door, Myra stopped and turned round. ‘Look, there’s no sense in you and me not getting on,’ she announced, making Diane warm to her more. ‘There’s a dance on at the Grafton Ballroom Saturday night. It’s the best ballroom in Liverpool and they have some smashing bands playing there. Why don’t you come along with me and see for yourself how much fun you can have?’

Diane was about to refuse when Myra added perceptively, ‘If this chap of yours has broken things off, then there’s no sense in coming here and moping about, if you want my opinion. What you should do is show him what you’re made of and have a darn good time. That’s certainly what I’d do. There’s no point looking back over your shoulder for a chap who doesn’t want you when there’s plenty around who would.’

‘What make you think that he was the one who broke the engagement?’ Diane demanded, her pride stung by Myra’s caustic words. ‘As a matter of fact, having a good time is exactly what I do intend to do,’ she added nonchalantly.

‘Good. You’ll be on for the dance, then?’

‘Of course.’ The acceptance was out of her mouth before Diane could summon the good sense to refuse.

‘Wait until you see them Yanks. You won’t be moping over your chap then, I can tell you, not if you’ve any sense,’ Myra told her enthusiastically as she opened the door.

‘I’m not moping…’ Diane began but it was too late, Myra had gone, clattering down the stairs.

Half an hour later, having thanked Mrs Lawson for her cup of tea and the Spam sandwiches she had made her, Diane dutifully listened whilst her landlady went through her house rules.

‘You’ll be well fed, or as good as I can manage,’ Mrs Lawson assured her. ‘All the chaps round here have allotments and, knowing I’m widowed and that I’m doing me bit having you girls here, they mek sure that I get me fresh veggies and fruit. Mind you, you’ll get some of your meals at the Derby House canteen, as well, so you won’t be going without.’ She gave a small sniff that wasn’t quite a criticism, but Diane took the hint.

‘If there’s anything going spare, I’ll make sure I bring it back with me, Mrs Lawson.’

She was rewarded with an approving smile.

‘You’re a sensible type, I can see that,’ the landlady told her. ‘Now, I’ll give you a key, ’cos I know you’ll be working shifts. I’m off out in a few minutes, once I’ve washed up, as it’s me WVS meeting night.’

‘I’ll give you a hand with the washing-up, shall I?’ Diane offered dutifully, earning herself another approving smile. She realised she would have to adapt so that she could get on well with both Mrs Lawson and Myra Stone if she was going to cope with life at number 24.

TWO

Left to her own devices, Diane decided that she might as well explore her new surroundings rather than stay cooped up in the room she was sharing with Myra.

She changed out of her uniform, taking care to hang it up neatly, before unpinning her hair. The trouble with being a natural blonde was that there were so many unnatural blondes around who had taken the maxim that blondes have more fun so enthusiastically to heart that one was judged automatically as being the same. It was part of the reason why she preferred to wear her hair up instead of down. But only part, Diane admitted. The other part was the fact that Kit had loved to smooth her hair back off her face and run his fingers through it, and now she just couldn’t bear to look in the mirror and see it falling softly down onto her shoulders. It was horrid to love someone so much when they no longer loved you back. Diane had never imagined she would feel like this. She had grown up in a happy loving environment, with parents married nearly thirty years now, and from the moment Kit had proposed to her she had simply accepted that he loved her and that he always would do.

She wasn’t to think about him any more, she reminded herself fiercely. He wasn’t worthy of her tears or her thoughts, and she had had a lucky escape. Better to have found out now what he was really like…

She had said these words to herself so often these last few weeks that they had become a litany that ran ceaselessly through her head. It had been very hard to maintain the pretence of their deciding on a mutual end to their engagement in front of her colleagues, especially those young women who, like her, had RAF boyfriends and with whom she and Kit had often socialised.

Not letting the side down had become not letting herself down, just as keeping a stiff upper lip in the face of the hardships of war had become making sure that she didn’t let others see how she really felt.

It wasn’t unknown for engagements to be broken, and though the ending of hers had been greeted with a few raised eyebrows, the camp was a large one and everyone there knew young women who had lost fiancés and husbands to the war, and who because of that were far more deserving of sympathy than Diane.

Out of Kit’s squadron only just over half of the original young pilots were still flying. One of Kit’s closest pals in the squadron had been shot down and killed, leaving a distraught young widow, so distraught in fact that she had tried to take her own life. Diane shivered, remembering poor little Amy. But it didn’t do to dwell on such things -the war taught everyone that. Amongst those pilots who weren’t flying were the dead, the injured and those who were presumed to be prisoners of war. Diane gave another shiver. She must not think about that now, nor about the nights she had lain awake, wondering if Kit would make it back safely. That life was over now. This was meant to be a fresh start for her here in Liverpool, where no one knew her or her history.

She looked down at her left hand and her bare ring finger. When Kit had broken their engagement she had taken off her ring and handed it back to him. He had shrugged dismissively, telling her that she might as well keep it, plainly unconcerned about either it or her any more. The following weekend, having given in to a friend’s suggestion that she join them at a dance, she had had the heart-stopping experience of seeing Kit dancing with another girl, holding her close as he crooned in her ear. But she couldn’t think about that again. The familiar pain was building up. She must not let it take hold of her. And she would not. Girls like Myra, with her cynical determination to make the most of the opportunities the war offered, had a far better time of it than girls like her, and if she had any sense she would model herself on Myra and have a good time herself. What, after all, had she got to lose now that she had lost Kit? He plainly was enjoying himself without her, and now that she had no heart left to break she would not be in any danger of having hers broken a second time, would she? It was all very well being good and loyal, and loving one man and one alone, but when that man said he didn’t want you any more where did that leave you? Diane took a deep breath. After all, hadn’t she already told herself that from now on things were going to be different and that she herself was going to be different? Sharing with someone like Myra was going to make it easy for her to keep that promise to herself. From now on she was going to go out and dance and laugh, and take all the fun that life was prepared to offer her. She reached up and tugged the pins out of her hair…

Ten minutes later, freshly dressed in ‘mufti’, as those in the forces referred to their non-uniform clothes, she let herself out of the house.

She might as well walk back into the city and find out the best way to reach Derby House, she decided when she had walked as far as Edge Hill Road. It was a light evening with a pleasant breeze, and she set off briskly in the direction she had come earlier.

The bombed buildings looked no less shocking this time than they had done earlier. Instinctively she wanted to look away. People had lived in those houses and worked in those buildings. Where were they now? Rehoused safely somewhere else, or had their lives been destroyed along with their homes, Diane wondered sadly, standing uncertainly at the crossroads she had come to and wondering which way she should take.

‘Summat up, is there, lass?’ a woman with a chirpy Liverpudlian accent asked her.

‘I’m just trying to get my bearings,’ Diane told her. ‘I’ve only just arrived…’

‘Aye, well, with that blonde hair of yours you’d better take care no one mistakes you for a German spy,’ the woman told her forthrightly. ‘I don’t hold wi’ bleaching, I don’t…’

Diane forced herself to smile, rather than correct her.

‘So what is it yer looking for then? If it’s them Yanks, yer won’t have to go far; they’ll find you soon enough. Not that I’d let any daughters of mine tek up wi’ one, not for all the fags and nylons in the world,’ the woman avowed firmly.

‘Actually, I was trying to make my way to Derby House,’ Diane told her.

‘Derby House, is it? Got business there, have yer?’

Diane had had enough. Out of the corner of her eye she could see a policeman walking towards her. Excusing herself, she hurried over to him, asking him determinedly, ‘I wonder if you could point me in the right direction for Derby House. I’m in the WAAF and I’m on duty there tomorrow.’

‘Got your papers with you, have you?’ he asked her.

Diane dutifully produced her identity documents for him to see.

‘Come with me. I’ll show you the way,’ he told her once he had studied them and handed them back to her.

Derby House turned out to be a disappointingly dull-looking new office block behind the town hall, but as Diane had learned from her briefing before leaving Cambridgeshire, the government knew that Hitler would seek to target the place that was the headquarters of the Western Approaches Command, so they had protected the real heart of the operation by building it underground.

The policeman had returned to his duties, leaving Diane to study the building on her own. Liverpool was so very different from the airfield where she had worked before, but then her whole life was going to be different from now on, without Kit and their plans for the future. A huge lump formed in her throat as desolation swept over her. She forced herself to swallow back the threatening emotions. There was no point feeling sorry for herself. She had to meet this head on and stiffen her spine against her own weakness. After all, she had asked for her transfer so that she could have a fresh start away from people who had known her and Kit, away from the whispered conversations and sidelong looks to which she had become so sensitive.

She took a deep breath and straightened her shoulders. On the other side of the road she could see and hear a group of girls giggling as they linked arms. Diane watched them, envying their happiness as they strolled out of sight.

And then, just as she was about to cross the road and make her way back to her billet, out of nowhere – or so it seemed – an army Jeep filled with American soldiers came roaring down the road.

‘Hey, guys,’ Diane heard one of them, who was hanging out of the window, yell, ‘I see dames…’

The girls Diane had been watching made their escape, breaking ranks to run off up an alleyway, laughing and squealing, whilst the Jeep skidded to a halt, then did an abrupt U-turn. Immediately Diane stepped back into the shadows. She had seen enough of the kind of high-spirited behaviour indulged in by young servicemen desperate for female company in their off-duty hours, and did not want to draw attention to herself. But it was too late: they had seen her and, deprived of their original prey, the driver of the Jeep pulled it up across the pavement, blocking off Diane’s exit.

‘Hey, pretty girl, how about we have some fun together?’ one of the men called out to her. ‘We got nylons, we got chocolate, we got gum…’

‘Yeah, and we got jackass hard ons like you’ve never seen…’

Somehow Diane managed to stop herself from going bright red as she heard the explicit description yelled out by one of the other men.

‘Hey, Polanski, leave it out, will ya?’ another voice joined in, before its owner urged Diane, ‘Come on, blondie, we could have a good time together. What d’ya say?’

Things were threatening to get out of hand, Diane recognised. She could smell the alcohol on their breath from where she was standing, and she was now alone in the street with them.

She forced herself to remain calm as she said as firmly as she could, ‘I say that you boys are going to get in big trouble if your military police find you in this state.’

‘Hey, will ya listen to that?’ another of the men drawled admiringly. ‘A ballsy dame. I like that…’

‘But not as much as you’d like it if it was your balls she was playing with, eh, Dwight?’ another man laughed.

Whilst it wasn’t true to say that she was scared, Diane knew she was feeling apprehensive. She was a sensible young woman who had no intention of reacting in the kind of silly way that would cause the situation to escalate but she was also aware that she was out of uniform and thus could not command the same kind of respect wearing it would have gained her. She decided she had to get away from these men.

‘If you’ll excuse me…’ she told them, stepping forward so that she could skirt past them.

But they wouldn’t let her go, and to her shock one of them jumped down from the Jeep and started to walk towards her.

Now she was scared, Diane admitted as another GI jumped down onto the road.

‘Come on, sweet stuff,’ the first one coaxed. ‘All we want is a bit of fun. We won’t hurt you, will we, guys?’ As he spoke he was reaching out to grab hold of her arm.

It was foolish to panic, Diane knew, but she couldn’t help it. Backing off from them, her voice high-pitched with tension, she demanded, ‘Stop this and let me go.’

‘Sure we’ll let you go, honey, once we’ve had our fun…’

She could hear them laughing as they started to crowd her, her fear giving them the power to be more insolent. Anger and shocked disbelief fought for supremacy inside her. This could not be happening. Not in broad daylight in the middle of the city.

‘Come on, blondie. You’ll enjoy it…’

‘What the hell’s going on here?’ The authoritative voice of the uniformed officer who had suddenly appeared out of nowhere acted on them like a physical barrage, making them fall back and suddenly look more like scared boys than young men.

‘Sorry, Major…’

‘Gee, Major…’

Muttering apologies and excuses, the men piled back into the Jeep, leaving Diane facing the tall, broad-shouldered and obviously furious officer.

‘Now, I don’t know who you are, but if you’ll take my advice, you’ll think yourself lucky that I came by when I did, and maybe next time you’ll think twice about encouraging my men to—’

Diane’s self-control snapped. ‘Encouraging them? I’ll have you know, Major, that I was doing no such thing. Your men were behaving in a way that would have got them court-martialled had they been British,’ Diane told him bitingly.

‘You must have encouraged them—’

‘I did no such thing! Their behaviour was inexcusable and it’s no wonder that parents are telling their daughters to keep away from Americans. Your men were behaving more like some kind of occupying force than allies.’ Diane had the bit between her teeth now and all the bitterness and misery of the last few weeks, as well as the fright she had had, were fuelling her fury.

The major was equally incensed. He took a step towards her, and Diane had a momentary impression of reined-in temper and sheer male physical strength as he towered over her. His hair was thick and very dark, and his eyes, she noticed, were a brilliantly intense shade of blue.

He could quite easily have been a film star, and the uniform he was wearing, so much smarter than the uniforms of the British forces, only served to add to that impression. For some reason that infuriated Diane almost as much as his accusations had done.

‘My men—’

‘Your men behaved like wild animals and you should be ashamed of them, not defending them. All I was doing was simply standing here.’

‘Oh, yeah? Then you can’t blame them for thinking you were waiting for business, can you?’

It took several seconds for his meaning to sink in through her anger, but once it had she drew herself up to her full height and told him icily, ‘I suppose I shouldn’t be shocked in view of the behaviour of your men, but somehow I am. You see, in this country, Major, we expect our officers to know better. Now if you’ll excuse me I need to return to my billet. I’m on duty at eight, and by on duty,’ she told him pointedly, ‘I mean that I shall be serving my country – in uniform, just so there isn’t any misunderstanding.’

Diane had the satisfaction of seeing the slow burn of colour creeping up under his skin.

‘OK, my boys may have made a mistake—’ he began grudgingly.

‘There was no “may” about it, Major. Perhaps you should invite them to tell you about the group of girls they were pursuing and lost when they charged down here in their Jeep – or maybe that’s acceptable behaviour for American servicemen?’

Without giving him the opportunity to respond, Diane stepped past him, keeping her head held high as she virtually marched up the street, away from him. Outwardly she might look fully in control but inwardly she was quaking in her shoes, she admitted, as she refused to give in to the temptation to turn round and see if he was watching her. It made her feel physically sick to think of what could have happened to her if he hadn’t turned up when he had, and it made her feel even more nauseous to recognise what he had thought of her and how he had condemned her without bothering to check his facts. She knew that there was already a lot of antagonism in some quarters towards the American soldiers who had arrived in the country, but until now she had felt that they were being treated a bit unfairly. Feeling superior because they had better uniforms and equipment was one thing, but behaving as they had towards her was something else again, Diane decided angrily. Did they really think they were so important that they could get away with treating decent British women like that? By the time she had reached Edge Hill Road, she had walked off some of her temper and was feeling calmer, but it wasn’t until she had closed the door of her bedroom behind her and dropped down onto her narrow bed that she realised how shaky the incident had left her feeling.

‘Oh, Kit,’ she whispered, wishing he could take her in his arms and comfort her. But it was no use crying for her ex-fiancé. He had made it plain that she meant nothing to him any more.

THREE

‘Come on, girls, we’d better get back to work. We’ve overrun our break by five minutes as it is.’

‘Another few minutes won’t do anyone any harm, Janet,’ Myra protested. ‘I haven’t finished my ciggy yet.’

‘Huh, you’re lucky to have any ciggies to finish,’ sniffed the third Waaf gathered round the canteen table in the Navy, Army, and Air Force Institute – or the Naafi as all the canteen facilities provided for the armed forces were affectionately nicknamed. ‘I suppose you’ve been cadging some off them Yanks again, have you? I saw you talking to that handsome corporal earlier on.’

‘He’s only a bit of a kid and he looked half scared to death,’ Janet Warner, the most senior member of their small group, said drily, adding under her breath, ‘Watch out – here comes Sergeant Riley.’

‘What’s this then, a mothers’ meeting? Haven’t you lot got any work to do?’

There was a sudden clatter and the scrape of chairs being pushed back as all the girls apart from Myra reacted to the sharp voice and hurried to the exit.

‘We’re just on our way, Sarge,’ Janet assured the thickset, sharp-eyed RAF sergeant who was surveying them before turning away to head for the counter.

‘Come on, Myra,’ Janet urged in a hissed whisper from the doorway as Myra took her time crushing out her cigarette before starting to stroll insolently towards her friends. ‘Sometimes I think you go out of your way to wind up Sergeant Riley I really do,’ Janet muttered crossly.

‘It gets on my nerves the way he throws his weight around and thinks he can tell us what to do.’

‘He’s a sergeant, Myra; he doesn’t “think” he can tell us what to do, he knows he can.’

‘Stone, over here.’

Myra hesitated just long enough to make the anxiety sharpen further in Janet’s eyes and to have the satisfaction of seeing the red tide of anger starting to burn up the sergeant’s face, before obeying his summons.

‘It’s your kind that give women in the services a bad name,’ he told her when she eventually reached him. ‘And if I had my way—’

‘But you don’t, do you, Sarge?’ Myra taunted him. ‘Have your way, I mean. We all heard about that little Wren turning you down. Shame. She’s dating an American now, I hear. And who can blame her? Good-looking lot, they are, and generous.’

‘You’ve got a husband who’s away fighting for his country.’

‘So I have.’

‘It hasn’t gone unnoticed that you’ve been carrying on like you are single.’

‘Hasn’t it?’ Myra gave a shrug. ‘So what?’

‘You ought to be ruddy well ashamed of yourself.’

‘Jealous, are you, Sarge, ’cos other people are having a good time and you aren’t? Well, I’ll tell you something, shall I? I don’t blame your little Wren for turning you down in favour of her Yank, not one little bit. In her shoes, I’d have done the same.’

‘Sarge, your tea’s going cold,’ the Naafi manageress called out.

The sergeant turned his head, giving Myra the opportunity to escape.

She and the sergeant had clashed from the moment they had set eyes on one another. He reminded her in many ways of her father. A small shadow darkened Myra’s eyes. How her mother had stuck him for so many years Myra didn’t know. Part of the reason she had married so quickly had been to escape her home. She hadn’t known then, of course, that her father would have a seizure in the middle of one of his furious outbursts of temper and die three months after the wedding.

Men! Once you let them get the upper hand they thought they could treat you how they liked. That was why she was determined that no man would ever control her life the way her father had controlled her mother’s and had tried to control hers. She wished passionately now that she had not been stupid enough to get married and land herself with a husband hanging around her neck and thinking he could tell her what to do. Well, he could write as many letters as he liked telling her he did not want her going out whilst he was away. They weren’t going to stop her doing a single thing that she wanted to do.

FOUR

Ruthie tensed as she opened the front door, her shoes gripped tightly in her free hand as she glanced fearfully over her shoulder into the blackout-shrouded darkness of the silent house, terrified of making the slightest sound that might wake her sleeping mother. If that happened…but no, she mustn’t think about that.

Once she was safely outside in the cold dawn air she slipped on her pair of Mary Jane shoes, polished over and over again to make them last as long as they could. It was summer now, but in the winter, wet shoes had to be stuffed with paper and left to dry out, not always successfully. Mothers did their best, warming their children’s thick hand-knitted socks on fire guards in an attempt to send them to school with warm dry feet, whilst young women submitted to the sensible habit of wearing thick lisle stockings, even though they itched dreadfully…

All Ruthie had to do now was make sure she reached the appointed place in time.

Her mother would never forgive her for this; she would tell her truthfully how shocked and upset her father would have been.

Her father! Ruthie paused outside the gate of the neat red-brick semi, not daring to risk putting the gate on the latch just in case the noise might alert her mother to her departure. It hurt so much to think about the way Dad had died, crushed beneath the masonry blown apart by the German bomb that had devastated the Durning Road Technical College in the autumn of 1940. He had been on duty there as an air-raid warden. Her mother, Ruthie knew, would never recover from his loss; it hung over the small house like the pall of smoke and dust that had hung over the destroyed college. When the news had come her mother had insisted on them going down there, even though she had been advised not to do so. The rescue work had still been going on when they had arrived – what could be salvaged of once living, breathing human beings, tenderly and respectfully brought out of the carnage. Ruthie knew she would never forget what she had seen that night: a human hand and wrist – thankfully not her father’s – the watch on it still going, a baby’s rattle, a woman’s torso, images too horrible for her to want to recall.

Ruthie had reached the Edge Hill Road now and she continued down into the area of terraced streets that lay below it, once filled with people’s homes but now ravaged by Hitler’s bombers’ assault on the city during the first week of May 1941, when Liverpool had endured a week-long blitz that had destroyed hundreds of buildings and killed so many people.

Had she come to the right place? She wasn’t sure and she started to fret, her hazel eyes darkening with anxiety as she pushed a nervous hand into her soft mousy brown hair. How long would she have to wait? She stared into the half-light, her heart thudding. She still couldn’t believe she was actually doing this. Her mother would be so shocked and so unforgiving. She could almost see the sad, gentle look her father would have given her if he knew.

She could hear the sound of a bus coming up the road towards her. Automatically she stiffened. She flagged down the driver and it pulled to a halt.

‘Is this the bus for the munitions factory?’ she asked anxiously as she stepped onto it.

The interior of the bus was packed with women, and one of them called up sarcastically, ‘Course it bloody is. What does it look like – a ruddy chara trip to Blackpool?’

Ruthie blushed bright red as the women burst out laughing. A pretty redhead with a mass of curls and smiling eyes looked Ruthie over and then said determinedly, ‘Give over, Mel. The poor kid looks half scared to death. Just starting, are you, love?’ she asked Ruthie, making room for her on the seat next to her.

Ruthie nodded, feeling tongue-tied and uncomfortable.

A lot of people said that it was only the poorer sort of women who signed on to work at the munitions factory at Kirby, and Ruthie suspected from the coarse language and dress of those on the bus that it was probably true. But she needed a job, and not just because now that she was nineteen it was compulsory for her to do war work. She and her mother needed the money, and she had heard that the munitions factory paid good wages, even to unskilled, untrained workers like her.

‘I must be daft in me head tekin’ on a ruddy job like this,’ the woman who had mocked Ruthie grumbled. ‘Up at four and working ruddy long shifts, and tekin’ me life into my hands every day.’

‘Come on, Mel, it isn’t as bad as that,’ the redhead that had offered Ruthie a seat objected. ‘The wages are good, and then there’s them concerts that the management put on for us, and these buses…’

‘Oh, trust you to say that, Jess Hunt. A right little ray of ruddy sunshine, you are. What about the danger then? There was that girl last week had all of her fingers blown off, she did. You could hear her screaming three sheds away,’ Mel announced with relish, whilst Ruthie sucked in her breath and fought back the nausea cramping her stomach.

It had been three days before they had found her father in all the rubble. Her mother had been too distraught to identify his body so Ruthie had had to do it. There hadn’t been a mark on his face – he looked like he was asleep – but where his feet should have been there had been nothing. Ruthie’s had been a innocent childhood, her parents loving and protective, but that single act of identifying her father’s body had stripped that innocence from her.

‘So what’s your name then,’ the redhead asked.

‘Ruthie Philpott,’ she responded.

‘Well, I’m Jess Hunt, and that there is Mel, and sitting next to her there is Leah, and behind her, Emily.’

‘Tell you what to expect, did they, when you went up for your interview?’ Mel asked.

Ruthie nodded her head.

‘Aye, well, it won’t be owt like that,’ Mel told her sourly. ‘A right rough lot some of them as works there are. I know of girls who’ve had to walk home in their bare feet on account of having their shoes pinched from them bags they give you to put your stuff in. That lot you’re wearing won’t be there when you go looking for it at the end of your shift,’ she warned Ruthie unkindly. ‘That’s why we allus wear our oldest stuff.’

‘I’m sorry, I don’t understand,’ Ruthie faltered.

‘Stop scaring her, Mel,’ Jess chipped in. ‘It’s all right, Ruthie, it’s just that when you have to get changed into the coveralls they make you wear, you have to put your own stuff in this bag they give you and then you hang it up on a peg, next to the locker they give you for your purse and that. Most of the time your things are safe enough until you come off shift but there’s a few there that aren’t as honest as they should be and it has been known for someone to find their bag’s empty. That’s why we all wear our oldest things.’

Ruthie was too shocked to be able to conceal her feelings.

‘Gawd, just look at her face,’ Mel said derisively. ‘A right know-nothing, this one is and no mistake. Green as grass, she is. You might as well get off the bus now ’cos you won’t last a day.’ Turning her back on Ruthie she added to one of the other girls in a voice easily loud enough for Ruthie to hear, ‘If you ask me they shouldn’t be tekin’ on folk like her, and time was when they wouldn’t have. She’s the kind that would have turned up her nose at our kind of work. There’s too many of her sort coming wanting jobs in munitions now on account of them having heard that the pay is good.’ She gave a derisive sniff. ‘Seems to me that whilst her sort thinks they’re too good to mix with the likes of us, as soon as there’s a sniff of a bit of money to be had they can’t wait to change their tune.’

Ruthie tried to pretend she hadn’t heard what Mel was saying and to look unaffected by it, but she could see from the quick look Jess was giving her that she hadn’t succeeded.

‘Come on, Mel, there’s a war on, remember,’ Jess broke into her complaint. ‘We’ve all got to do our duty.’

‘Oh, aye, but I’m not daft, and if you ask me it isn’t just doing their duty that’s bringing her sort into munitions. Like I just said, she wouldn’t be wanting to work wi’ the likes of us if it weren’t for the good wages.’

Ruthie could feel her face burning with self-consciousness and guilt. It was true that the only reason she had been able to steel herself to apply for a job at the munitions factory was because of the high rate of pay and because it would mean that she didn’t have to leave her mother living on her own, like she would have had to do if she had joined the ATS or one of the other women’s services. To her relief she realised that the bus was pulling up to the factory gates.

‘Come on,’ Jess said. ‘We all have to get off here.’ A little uncertainly Ruthie followed the other girls towards the small opening in the factory gates. Her instructions were that she was to present herself at the factory as a new worker, but as she watched the women, who all seemed to know exactly what they were doing, streaming towards the gates from the buses, Ruthie began to panic. She had lost sight of the girls she had been on the bus with already, and even though she had only known them half an hour and had not exactly been welcomed amongst them, she would have liked the comfort of their presence. She looked desperately towards the gate, trying to remember what exactly she was supposed to do and where she was supposed to go. Why had she done this? Mel was right: she did not fit in here with these girls, she was an outsider amongst them – and right now she felt sick with nerves and misery. She tensed as she felt a quick tug on her sleeve, remembering Mel’s warning and half fearing that her top was going to be torn from her, but when she turned round it was Jess, her eyes crinkled up with a reassuring smile.

‘It’s bloody bedlam here this morning,’ she puffed as she managed to stop them from being parted by the press of girls making for the gate. ‘I just came back to tell you that you’ll have to tell them on the gate that you’re new. There’ll be other girls who’ll be starting today and they’ll keep you back and then get you sorted out. Ta-ra, now, and good luck.’ Jess wriggled back through the crowd.

‘Wait, please…’ Ruthie begged her. There was so much she didn’t know, and Jess’s jolly manner had been comforting in the alien surroundings of this frightening new world. But it was too late: Jess had already disappeared into the mass of women milling around.

‘Here, you. New, are you?’ a brisk voice demanded sharply, as a stern-looking woman gave Ruthie a sharp dig in her arm.

‘Yes. Yes, I am,’ Ruthie confirmed.

‘Name?’ the official demanded, making ready to write it down on the clipboard she was holding.

‘Ruthie…’ Ruthie answered her, flushing when the woman demanded witheringly, ‘Ruthie what? Lord save us, my cat’s got more nous than this one,’ she announced to no one in particular. Some of the other women, waiting by the gate, laughed.

‘Ruthie Philpott.’

‘Right. Next…?’

‘OK, are you? Only I heard her over there mekin’ fun of you, when we was waiting to be let in.’ Ruthie blinked away the tears that were threatening, to focus on the young woman who had just addressed her. She was a well-built girl with small pale eyes, and a sharp glance that seemed to be looking everywhere but directly at her, as though she was looking around for someone or something more interesting, but Ruthie was too grateful for her kindness to be critical.

‘Not giving her my surname was such a stupid thing to do.’

‘Aye, well, we all do daft stuff at times and anyone can see that you’re a bit out of yer depth, like. Couldn’t get into any of the services, like, could yer not? Same here. Tried for the ATS, I did, but they wouldn’t have me on account of me having flat feet.’

‘I needed work that would let me stay at home. It’s my mother, you see,’ Ruthie heard herself explaining.

‘Wanted yer to tip up at home and give her wot you was earning, did she? My mam’s like that, an’ all. Seems to me like you and me ’ave got summat in common and we should stick together.’ She gave a disparaging sniff. ‘There’s some right common sorts working here. Thieving and Lord knows what goes on, so I’ve heard.’

Ruthie could only nod her head. She wasn’t used to having her friendship courted. Suddenly her new life didn’t seem as threatening as it had done. ‘I’d like that,’ she offered shyly.

‘Aye, well, my name’s Maureen, Maureen Smith.’

‘Ruthie…’ Ruthie began, but Maureen snickered and shook her head.

‘Aye, I know I heard you telling it to her wot’s in charge, didn’t I? Live on Chestnut Close, you told her. So where’s that when it’s at home?’

‘It’s between Edge Hill and Wavertree.’

‘Oh ho, you’ll be a bit posh then, will yer, living up there?’

‘No, of course not,’ Ruthie denied. There was something about the way Maureen was looking at her that made her feel slightly uncomfortable.

‘Course you are. Anyone can tell just by looking at yer. Them nice clothes you’re wearing. Got much family, ’ave yer?’

‘No. It’s just me and my mother.’

‘Well, you’re the lucky one then and no mistake. Our house is that full wi’ me mam and da, and me and me sisters, two of them with kiddies of their own, living in it, a person doesn’t have room to breathe. I’m going to be looking for a new billet just as soon as I’ve got a bit of money together from working here.’

‘Right you lot, this way…’

‘Let them others go first,’ Maureen advised Ruthie with a warning nudge as she prepared to obey the overseer’s command. ‘Then we can tag on at the end, like. It don’t do to get yerself too much noticed by them wot’s in charge. Yer don’t want ter seem too eager.’

Ruthie allowed her new friend to take the lead. She gulped as she took her first step into her new world, wondering what on earth she had let herself in for. Far from being exciting, right now this new life of hers threatened to be alien and frightening.

FIVE

Her presence on the streets of Liverpool was certainly being treated with a good deal more respect this morning than it had been last night, Diane admitted, as she walked briskly past the town hall, heading for Derby House. No doubt the fact that she was wearing her uniform had something to do with that. It was a sunny morning but cool enough for her not to feel uncomfortable in her tailored skirt and jacket. Her hair was rolled into a neat French pleat and, unlike some of the girls she knew, she was wearing her cap at the correct angle and not some jaunty and flirtatious version designed to attract male attention.

As she reached the building, the night shift was just coming out, their faces stiff and pallid from the long hours of concentration.

‘Keen, aren’t you? The next shift doesn’t start for another half-hour yet.’

Diane stopped in mid-step when she realised that the question had come from Myra, who was leaning back against the wall of the building, lighting up a cigarette.

‘Yes. I thought I’d get here a bit earlier, just to be on the safe side. I’ve got to report to a Group Captain Barker.’

‘Nanny Barker. She’s OK but a bit of a fusspot. You’ll have to watch out for her sidekick, though, Warrant Officer Whiteley – hates good-looking girls, she does.’ Myra pulled a face. ‘She’s got a real down on me.’ She stifled a yawn. ‘I’m for my bed. I’ve got a hot date with a GI this afternoon. He’s taking me to a matinée. He should be good for a box of nylons if I play my cards right.’

Diane smiled noncommittally.

‘I could fix us up with a double date for later in the week, if you fancy it?’

‘No, thanks.’ Diane refused, adding when she saw Myra’s expression begin to darken, ‘I’m up for going dancing and having a bit of fun, but I don’t plan to date.’

‘Well, it’s your loss,’ Myra shrugged. ‘And it means more men for me!’

‘Glad to have you on board, Wilson. Know much about our ops here, do you?’

‘Nanny Barker’ had turned out to be a sturdy-looking woman in her early forties, with a hearty no-nonsense manner. Without waiting for Diane to reply she continued, ‘According to your previous CO, you’re a quick learner, so I’m going to put you on one of the new teams we’ve set up. I’ll show you round first and explain to you what we’re doing.

‘In January of this year Captain Gilbert Roberts established the Western Approaches Tactical Unit here. It’s based officially on the top floor of the Exchange Building, which is close to here. Captain Roberts and his team study U-boat tactics and then develop effective countermeasures. The unit runs six-day training courses for Allied naval officers to help them improve the tactics they use in their escort groups.

‘Over here in Derby House the Senior Service and the RAF work together on joint Atlantic ops along with some of our American allies to protect the convoys crossing the Atlantic. Senior Service has overall control, but we have an important part to play. It’s our RAF reconnaissance planes that provide vital forward information – as a Waaf you’ll be involved in working on that info. Follow me,’ Group Captain Barker instructed Diane, leading the way to a flight of stairs.

‘Down here is the nerve centre of the ops. It’s bomband gas-proof,’ she told Diane with evident pride as she led her down to what Diane guessed must be a large basement area. ‘We’ve got all the regulation emergency areas, just in case – dorms, ablutions, the Commander-in-Chief’s private quarters, in addition to the telecommunications room, and a couple of off-duty areas.’ She paused to return the salute of a pair of naval ratings on guard duty in front of a large door.

‘You won’t be permitted to come down here without your pass, so don’t forget to carry it with you whenever you are on duty,’ she warned Diane as the guards opened the doors for them.

Diane had, of course, seen operations rooms before and was familiar with their set-up, but the sheer size of this one took her aback. A huge map of the North Atlantic dominated one wall, whilst filling the centre of the room was a massive table holding an enormous situation map. Around it Wrens were busily moving models of the various convoys to show their deployment. There must have been nearly fifty Wrens working in the room, as well as a good-size bunch of Waafs, Diane calculated as she watched them for a few seconds before switching her attention to the wall bearing a map of the waters around Britain. More Wrens were perched on ladders, updating the maps and the reports chalked on large blackboards.

‘Over there is the Aircraft State Board,’ the Group Captain told Diane, nodding to the rear of the room, where a board showed the readiness of all the RAF stations displayed, as well as up-to-the-minute information about on-going air operations, brought in from the teleprinter rooms close at hand. There was also a weather board, and the noise from the different orders being called out was so deafening that at first it made Diane wince. It would take some concentration to learn to listen only to her own instructions and blot out the rest, she acknowledged, as she watched the control room’s busyness.

‘We’ve just lost a couple of our ops room operatives, so you’ll be working down here to start with, instead of going into the teleprinter communications room, which is where we usually put the new girls to start off with. Normally we don’t put girls down here until we’ve had time to assess them, but since the powers that be have seen fit to poach some of our best girls we don’t have much option. I’m prepared to take a chance on you.’

Diane tried to look suitably gratified, but the truth was that she was feeling slightly intimidated by the activity of the ops room and would have welcomed a more gradual introduction to it.

‘One of your duties will be to show our training groups how the system works. We’re getting a lot of American service personnel coming along to see how we do things here at the moment. Any questions?’

‘No, ma’am.’

‘Good-oh. I’ll hand you over to Corporal Bennett, then. She’s in charge of the team you’re going to be on.’

To Diane’s relief the young woman the captain introduced her to looked a sensible sort, around her own age, Diane guessed, although the light in ‘the Dungeon’ – as Myra had informed her the ops room was nicknamed – didn’t do her pale skin any favours. She was also, Diane saw with a sharp pang, wearing a gleaming wedding ring. Lucky her. Her chap hadn’t changed his mind, then.

‘Good to have you with us, Wilson,’ the other young woman welcomed her after the Group Captain had introduced them. ‘Done much of this sort of thing before, have you?’

‘No, I’m afraid not, Corporal Bennett,’ Diane admitted. ‘I was working as a teleprinter before I came here.’

Out of the corner of her eye Diane caught the resigned looks exchanged by the other four girls making up the team of which she was now to be part. Instantly she pulled herself up to her full height and said firmly, ‘I’m willing to learn, though.’

‘You’re going to need a keen eye and be quick off the mark. Men’s lives will depend on you. We can’t afford any mistakes, not with so much at stake,’ Corporal Bennett warned her. ‘You’d better partner me so that I can show you what we do and keep an eye on you. I’m Susan, by the way.’

‘Diane.’

Diane carefully memorised the names of the other girls on the team as they were introduced to her. Liz, Jean, Pauline and another Susan, this one to be addressed as Sue, she reminded herself as she mentally catalogued them all. Liz was the one with the serious, almost mournful expression and the short dark straight hair. Jean was tall and thin, and rather earnest-looking, with prominent blue eyes, and she was wearing an engagement ring. Pauline was small with brown curls. Sue was also engaged. Diane promised herself that she would remember them all. She sensed that these young women took their work very seriously and that they would be quick to consider her less than able if she couldn’t manage to do something as simple as remember their names.

Three hours later, despite her initial reservations, when Susan gave an approving nod of her head and told her crisply, ‘You’ll do,’ Diane felt a real glow of pride. Kit would laugh when she told him…Just in time she caught herself up, the small thrill of her success obliterated. Just for a few minutes she had been so engrossed in what she was doing she had forgotten that her engagement was over, her heart was broken. She instinctively reached for the place on her left hand where she had worn Kit’s ring.

‘Ooh, look who’s just walked in,’ she heard Pauline announcing happily in a soft whisper, ‘and he’s coming over here.’

‘Stow it, Pauline,’ Susan advised firmly. ‘We all know you think a certain American major is the best thing since Clark Gable, but there’s a war on, remember.’

‘No, I don’t. Major Saunders is ten times better-looking than Clark Gable,’ Pauline replied, unabashed. The others laughed. Diane joined in, willing to be a part of the little group, and then turned her head to get a better look at the subject of the conversation. A tall, dark-haired man in the distinctive uniform of the United States Army was striding determinedly towards them, accompanied by a rather youthful-looking RAF flight lieutenant. An unpleasantly familiar tall, dark-haired man, Diane acknowledged, her heart sinking as she recognised that the major was the man she had crossed verbal swords with the previous evening. Instinctively she shrank back into the shadows, trying to conceal herself behind the other girls. It was unlikely, surely, that the major would recognise her. She had the advantage over him of having seen him last night in uniform whereas he had only seen her in mufti. However, although she tried to make herself as unnoticeable as possible, Diane could feel the major’s sharp-eyed gaze falling and resting on her. Her face started to burn.

It was the flight lieutenant who broke the tension, saying cheerily, ‘Thought I’d bring the major across so he can take a look at how we keep tabs on things. Major, you’ll—’ He broke off as he saw Diane and exclaimed admiringly, ‘You’ve got a new recruit to your team, I see, Susan. Aren’t you going to introduce me?’

The major had recognised her, Diane realised, as she was subjected to a second and very chilling visual assessment, which, unlike that of the young flight lieutenant, did not contain any scrap of male approval.

‘I’m sorry, Flight Lieutenant,’ Susan began formally, but to Diane’s astonishment the young officer burst out laughing and then said cheerfully, ‘Oh, I say, sis, give a chap a chance, won’t you, and introduce me to this lovely girl?’

‘Wilson, I apologise for my brother,’ Susan told Diane ruefully. ‘Teddy, I am sure that Diane does not want to have some barely-out-of-short-pants and still-wet-behind-the-ears, just-made-up flight lieutenant pestering her.’

‘Oh, I say, that’s not fair, is it, Diane? I’m sure you’re just the kind of girl who is kind enough to take pity of a poor young officer.’

Blond-haired, with laughing blue eyes and an engaging smile, he was very amusing, Diane acknowledged, and a type she knew very well from Cambridgeshire. Helplessly young and brave, hopelessly full of high spirits and idealism, he couldn’t be a day over twenty-one, Diane guessed. She had seen so many of them, and seen them too after the reality of war had driven the youth from their eyes and replaced it with desperate bleakness. Her own Kit had been one – once.

Susan rolled her eyes. ‘Diane, once again, I do apologise for my ridiculous little brother.’

Diane laughed and shook her head, exchanging an understanding look with Susan. ‘I know all about younger brothers from my time in my previous posting,’ she assured her, deliberately not naming her previous post, in accordance with wartime regulations. As the posters had it, ‘Careless Talk Costs Lives.’ Not, she suspected, that there were likely to be any German spies here.

‘You promised the folks you’d take care of me and here you are refusing to introduce me to the most stunning girl I’ve ever seen.’

‘What happened to that redheaded Wren you were raving about last week?’ Susan teased him, relaxing when she saw that Diane was neither going to take offence nor read anything into his flattery.

‘What Wren?’ he demanded, looking injured.

‘I don’t want to break up the party, Flight Lieutenant, but if you don’t mind .. .’ The major’s voice had a hard edge to it for all the softness of his American accent. Susan looked uncomfortable and her brother crestfallen, whilst Diane was conscious of the condemning look the major was giving her. Well, let him think what he liked. She didn’t care. She knew the truth about herself. Diane lifted her chin and returned his look with one of her own – the kind she used to make it plain to overeager young men that she was not interested.

To her satisfaction she could see first disbelief, then incredulity followed by anger in the major’s eyes. That would teach him to look down on an Englishwoman, she decided sturdily.

‘Thanks for letting my wretched brother down lightly, Diane.’ They were in the canteen, having their break. Susan offered Diane a cigarette, which she refused. Diane had been horridly sick the first time she had smoked a cigarette – illicitly, of course, behind the church after Sunday school – and she hadn’t really smoked very much since apart from the odd social cigarette.