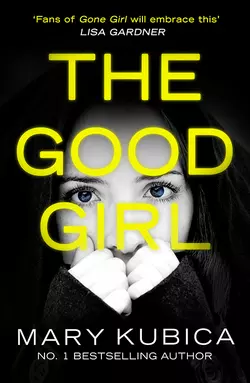

The Good Girl: An addictively suspenseful and gripping thriller

Mary Kubica

‘A tremendous read’ - The SunNow optioned for a major movie by the company behind Winter’s Bone, Babel, Being John Malkovich and the TV series True Detective.A compulsive debut that reveals how, even in the perfect family, nothing is as it seems…I've been following her for the past few days. I know where she buys her groceries, where she has her dry cleaning done, where she works. I don't know the colour of her eyes or what they look like when they're scared. But I will.Mia Dennett can't resist a one-night stand with the enigmatic stranger she meets in a bar.But going home with him might turn out to be the worst mistake of Mia's life…

“I’ve been following her for the past few days. I know where she buys her groceries, where she has her dry cleaning done, where she works. I don’t know the color of her eyes or what they look like when she’s scared. But I will.”

Born to a prominent Chicago judge and his stifled socialite wife, Mia Dennett moves against the grain as a young inner-city art teacher. One night, Mia enters a bar to meet her on-again, off-again boyfriend. But when he doesn’t show, she unwisely leaves with an enigmatic stranger. With his smooth moves and modest wit, at first Colin Thatcher seems like a safe one-night stand. But following Colin home will turn out to be the worst mistake of Mia’s life.

Colin’s job was to abduct Mia as part of a wild extortion plot and deliver her to his employers. But the plan takes an unexpected turn when Colin suddenly decides to hide Mia in a secluded cabin in rural Minnesota, evading the police and his deadly superiors. Mia’s mother, Eve, and detective Gabe Hoffman will stop at nothing to find them, but no one could have predicted the emotional entanglements that eventually cause this family’s world to shatter.

An addictively suspenseful and tautly written thriller, The Good Girl is a propulsive debut that reveals how even in the perfect family, nothing is as it seems….

MARY KUBICA holds a Bachelor of Arts degree from Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, in History and American Literature. She lives outside of Chicago with her husband and two children and enjoys photography, gardening and caring for the animals at a local shelter. The Good Girl is her first novel. Visit her website, www.MaryKubica.com (http://www.MaryKubica.com).

Mary Kubica

ISBN: 978-1-472-07472-0

THE GOOD GIRL

© 2014 Mary Kubica

Published in Great Britain 2014

by HQ, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. This edition is published by arrangement with Harlequin Books S.A.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, locations and incidents are purely fictional and bear no relationship to any real life individuals, living or dead, or to any actual places, business establishments, locations, events or incidents. Any resemblance is entirely coincidental.

By payment of the required fees, you are granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right and licence to download and install this e-book on your personal computer, tablet computer, smart phone or other electronic reading device only (each a “Licensed Device”) and to access, display and read the text of this e-book on-screen on your Licensed Device. Except to the extent any of these acts shall be permitted pursuant to any mandatory provision of applicable law but no further, no part of this e-book or its text or images may be reproduced, transmitted, distributed, translated, converted or adapted for use on another file format, communicated to the public, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of publisher.

Version: 2018-07-10

For A & A

Contents

Cover (#u307b5cda-a46e-5e2f-a593-88d2a17854c4)

Back Cover Text (#u9b666e6b-8be0-5472-b38c-5fecccbfd550)

Title Page (#ud040f003-b94a-505c-8982-51368a57789e)

Copyright (#u7ac28835-f793-5746-b314-2407cb09cd0d)

Dedication (#ud8701405-59a7-520f-8ed7-1754f9d268cc)

Eve Before (#u6a3e0297-f0d7-5373-96c7-f7c4b6d13123)

Gabe Before (#uf82175b9-9fa8-580a-a533-c775b95f97d2)

Eve After (#u0f3b7741-d2a9-5d31-b7ca-d8bb4c571b95)

Gabe Before (#uba420164-7286-5816-99b7-4ff2a295a254)

Eve After (#u40a1cb44-01bf-58b1-a960-ade8b42edd97)

Gabe Before (#u822a71d1-716f-5043-9340-2ff4e9c7a748)

Colin Before (#u7902f5fb-49f2-5095-9834-65b3fa602c4c)

Eve After (#u081dbfea-d82a-545c-973a-c82929a333e6)

Colin Before (#u12078259-ac9a-5315-9c72-2d064c831273)

Gabe After (#uef97d630-43a5-543f-8501-4542c61b1b9e)

Colin Before (#u4c34bb88-a564-5bba-a229-72900d680b05)

Eve After (#u0799700e-18d1-520f-81fa-6b219a1bf665)

Colin Before (#u69ee1728-ebca-516d-a7eb-3657a4e6ae5d)

Eve After (#u5ced7670-f152-5f2e-a36a-ed2f1c5b5eb4)

Colin Before (#uce92e8a9-314e-5141-a554-3cd1ec625368)

Gabe Before (#uf968fac8-d5f5-55b7-8bad-fd4b2d022a6a)

Colin Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Eve Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Colin Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Gabe Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Colin Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Eve Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Colin Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Gabe Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Colin Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Eve After (#litres_trial_promo)

Colin Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Gabe Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Colin Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Eve Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Colin Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Gabe Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Colin Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Eve Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Colin Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Gabe Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Colin Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Eve After (#litres_trial_promo)

Colin Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Eve After (#litres_trial_promo)

Colin Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Gabe Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Colin Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Gabe Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Colin Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Eve Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Colin Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Gabe After (#litres_trial_promo)

Colin Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Eve After (#litres_trial_promo)

Colin Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Eve After (#litres_trial_promo)

Colin Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Gabe Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Colin Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Gabe After (#litres_trial_promo)

Colin Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Eve Christmas Eve (#litres_trial_promo)

Colin Before (#litres_trial_promo)

Eve After (#litres_trial_promo)

Gabe Christmas Eve (#litres_trial_promo)

Colin Christmas Eve (#litres_trial_promo)

Eve After (#litres_trial_promo)

Colin Christmas Eve (#litres_trial_promo)

Gabe Christmas Eve (#litres_trial_promo)

Eve After (#litres_trial_promo)

Gabe Christmas Eve (#litres_trial_promo)

Gabe After (#litres_trial_promo)

Eve After (#litres_trial_promo)

Gabe After (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publishers (#litres_trial_promo)

Eve

Before

I’m sitting at the breakfast nook sipping from a mug of cocoa when the phone rings. I’m lost in thought, staring out the back window at the lawn that now, in the throes of an early fall, abounds with leaves. They’re dead mostly, some still clinging lifelessly to the trees. It’s late afternoon. The sky is overcast, the temperatures doing a nosedive into the forties and fifties. I’m not ready for this, I think, wondering where in the world the time has gone. Seems like just yesterday we were welcoming spring and then, moments later, summer.

The phone startles me and I’m certain it’s a telemarketer, so I don’t initially bother to rise from my perch. I relish the last few hours of silence I have before James comes thundering through the front doors and intrudes upon my world, and the last thing I want to do is waste precious minutes on some telemarketer’s sales pitch that I’m certain to refuse.

The irritating noise of the phone stops and then starts again. I answer it for no other reason than to make it stop.

“Hello?” I ask in a vexed tone, standing now in the center of the kitchen, one hip pressed against the island.

“Mrs. Dennett?” the woman asks. I consider for a moment telling her that she’s got the wrong number, or ending her pitch right there with a simple not interested.

“This is she.”

“Mrs. Dennett, this is Ayanna Jackson.” I’ve heard the name before. I’ve never met her, but she’s been a constant in Mia’s life for over a year now. How many times have I heard Mia say her name: Ayanna and I did this...Ayanna and I did that.... She is explaining how she knows Mia, how the two of them teach together at the alternative high school in the city. “I hope I’m not interrupting anything,” she says.

I catch my breath. “Oh, no, Ayanna, I just walked in the door,” I lie.

Mia will be twenty-five in just a month: October 31st. She was born on Halloween and so I assume Ayanna has called about this. She wants to plan a party—a surprise party?—for my daughter.

“Mrs. Dennett, Mia didn’t show up for work today,” she says.

This isn’t what I expect to hear. It takes a moment to regroup. “Well, she must be sick,” I respond. My first thought is to cover for my daughter; she must have a viable explanation why she didn’t go to work or call in her absence. My daughter is a free spirit, yes, but also reliable.

“You haven’t heard from her?”

“No,” I say, but this isn’t unusual. We go days, sometimes weeks, without speaking. Since the invention of email, our best form of communication has become passing along trivial forwards.

“I tried calling her at home but there’s no answer.”

“Did you leave a message?”

“Several.”

“And she hasn’t called back?”

“No.”

I’m listening only halfheartedly to the woman on the other end of the line. I stare out the window, watching the neighbors’ children shake a flimsy tree so that the remaining leaves fall down upon them. The children are my clock; when they appear in the backyard I know that it’s late afternoon, school is through. When they disappear inside again it’s time to start dinner.

“Her cell phone?”

“It goes straight to voice mail.”

“Did you—”

“I left a message.”

“You’re certain she didn’t call in today?”

“Administration never heard from her.”

I’m worried that Mia will get in trouble. I’m worried that she will be fired. The fact that she might already be in trouble has yet to cross my mind.

“I hope this hasn’t caused too much of a problem.”

Ayanna explains that Mia’s first-period students didn’t inform anyone of the teacher’s absence and it wasn’t until second period that word finally leaked out: Ms. Dennett wasn’t here today and there wasn’t a sub. The principal went down to keep order until a substitute could be called in; he found gang graffiti scribbled across the walls with Mia’s overpriced art supplies, the ones she bought herself when the administration said no.

“Mrs. Dennett, don’t you think it’s odd?” she asks. “This isn’t like Mia.”

“Oh, Ayanna, I’m certain she has a good excuse.”

“Such as?” she asks.

“I’ll call the hospitals. There’s a number in her area—”

“I’ve done that.”

“Then her friends,” I say, but I don’t know any of Mia’s friends. I’ve heard names in passing, such as Ayanna and Lauren and I know there’s a Zimbabwean on a student visa who’s about to be sent back and Mia thinks it’s completely unfair. But I don’t know them, and last names or contact information are hard to find.

“I’ve done that.”

“She’ll show up, Ayanna. This is all just a misunderstanding. There could be a million reasons for this.”

“Mrs. Dennett,” Ayanna says and it’s then that it hits me: something is wrong. It hits me in the stomach and the first thought I have is myself seven or eight months pregnant with Mia and her stalwart limbs kicking and punching so hard that tiny feet and hands emerge in shapes through my skin. I pull out a barstool and sit at the kitchen island and think to myself that before I know it, Mia will be twenty-five and I haven’t so much as thought of a gift. I haven’t proposed a party or suggested that all of us, James and Grace and Mia and me, make reservations for an elegant dinner in the city.

“What do you suggest we do, then?” I ask.

There’s a sigh on the other end of the line. “I was hoping you’d tell me Mia was with you,” she says.

Gabe

Before

It’s dark by the time I pull up to the house. Light pours from the windows of the English Tudor home and onto the tree-lined street. I can see a collection of people hovering inside, waiting for me. There’s the judge, pacing, and Mrs. Dennett perched on the edge of an upholstered seat, sipping from a glass of something that appears to be alcoholic. There are uniformed officers and another woman, a brunette, who peers out the front window as I come to a sluggish halt in the street, delaying my grand entrance.

The Dennetts are like any other family along Chicago’s North Shore, a string of suburbs that lines Lake Michigan to the north of the city. They’re filthy rich. It’s no wonder that I’m procrastinating in the front seat of my car when I should be making my way up to the massive home with the clout I’ve been led to believe I carry.

I think of the sergeant’s words before assigning the case to me: Don’t fuck this one up.

I eye the stately home from the safety and warmth of my dilapidated car. From the outside it’s not as colossal as I envision the interior to be. It has all the old-world charm an English Tudor has to offer: half-timbering and narrow windows and a steep sloping roof. It reminds me of a medieval castle.

Though I’ve been strictly warned to keep it under wraps, I’m supposed to feel privileged that the sergeant assigned this high-profile case to me. And yet, for some reason, I don’t.

I make my way up to the front door, cutting across the lawn to the sidewalk that leads me up two steps, and knock. It’s cold. I thrust my hands into my pockets to keep them warm while I wait. I feel ridiculously underdressed in my street clothes—khaki pants and a polo shirt that I’ve hidden beneath a leather jacket—when I’m greeted by one of the most influential justices of the peace in the county.

“Judge Dennett,” I say, allowing myself inside. I conduct myself with more authority than I feel I have, displaying traces of self-confidence that I must keep stored somewhere safe for moments like this. Judge Dennett is a considerable man in size and power. Screw this one up and I’ll be out of a job, best-case scenario. Mrs. Dennett rises from the chair. I tell her in my most refined voice, “Please, sit,” and the other woman, Grace Dennett, I assume, from my preliminary research—a younger woman, likely in her twenties or early thirties—meets Judge Dennett and me in the place where the foyer ends and the living room begins.

“Detective Gabe Hoffman,” I say, without the pleasantries an introduction might expect. I don’t smile; I don’t offer to shake hands. The girl says that she is in fact Grace, whom I know from my earlier legwork to be a senior associate at the law firm of Dalton & Meyers. But it takes nothing more than intuition to know from the get-go that I don’t like her; there’s an air of superiority that surrounds her, a looking down on my blue-collar clothing and a cynicism in her voice that gives me the willies.

Mrs. Dennett speaks, her voice still carrying a strong British accent, though I know, from my previous fact-finding expedition, that she’s been in the United States since she was eighteen. She seems panicked. That’s my first inclination. Her voice is high-pitched, her fingers fidgeting with anything that comes within reach. “My daughter is missing, Detective,” she sputters. “Her friends haven’t seen her. Haven’t spoken to her. I’ve been calling her cell phone, leaving messages.” She chokes on her words, trying desperately not to cry. “I went to her apartment to see if she was there,” she says, then admits, “I drove all the way there and the landlord wouldn’t let me in.”

Mrs. Dennett is a breathtaking woman. I can’t help but stare at the way her long blond hair falls clumsily over the conspicuous hint of cleavage that pokes through her blouse, where she’s left the top button undone. I’ve seen pictures before of Mrs. Dennett, standing beside her husband on the courthouse steps. But the photos do nothing compared to seeing Eve Dennett in the flesh.

“When is the last time you spoke to her?” I ask.

“Last week,” the judge says.

“Not last week, James,” Eve says. She pauses, aware of the annoyed look on her husband’s face because of the interruption, before continuing. “The week before. Maybe even the one before that. That’s the way our relationship is with Mia—we go for weeks sometimes without speaking.”

“So this isn’t unusual then?” I ask. “To not hear from her for a while?”

“No,” Mrs. Dennett concedes.

“And what about you, Grace?”

“We spoke last week. Just a quick call. Wednesday, I believe. Maybe Thursday. Yes, it was Thursday because she called as I was walking into the courthouse for a hearing on a motion to suppress.” She throws that in, just so I know she’s an attorney, as if the pin-striped blazer and leather briefcase beside her feet didn’t already give that away.

“Anything out of the ordinary?”

“Just Mia being Mia.”

“And that means?”

“Gabe,” the judge interrupts.

“Detective Hoffman,” I assert authoritatively. If I have to call him Judge he can certainly call me Detective.

“Mia is very independent. She moves to the beat of her own drum, so to speak.”

“So hypothetically your daughter has been gone since Thursday?”

“A friend spoke to her yesterday, saw her at work.”

“What time?”

“I don’t know... 3:00 p.m.”

I glance at my watch. “So, she’s been missing for twenty-seven hours?”

“Is it true that she’s not considered missing until she’s been gone for forty-eight hours?” Mrs. Dennett asks.

“Of course not, Eve,” her husband replies in a degrading tone.

“No, ma’am,” I say. I try to be extracordial. I don’t like the way her husband demeans her. “In fact, the first forty-eight hours are often the most critical in missing-persons cases.”

The judge jumps in. “My daughter is not a missing person. She’s misplaced. She’s doing something rash and negligent, something irresponsible. But she’s not missing.”

“Your Honor, who was the last one to see your daughter then, before she was—” I’m a smart-ass and so I have to say it “—misplaced?”

It’s Mrs. Dennett who responds. “A woman named Ayanna Jackson. She and Mia are co-workers.”

“Do you have a contact number?”

“On a sheet of paper. In the kitchen.” I nod toward one of the officers, who heads into the kitchen to get it.

“Is this something Mia has done before?”

“No, absolutely not.”

But the body language of Judge and Grace Dennett says otherwise.

“That’s not true, Mom,” Grace chides. I watch her expectantly. Lawyers just love to hear themselves speak. “On five or six different occasions Mia disappeared from the house. Spent the night doing God knows what with God knows whom.”

Yes, I think to myself, Grace Dennett is a bitch. Grace has dark hair like her dad’s. She’s got her mother’s height and her father’s shape. Not a good mix. Some people might call it an hourglass figure; I probably would, too, if I liked her. But instead, I call it plump.

“That’s completely different. She was in high school. She was a little naive and mischievous, but...”

“Eve, don’t read more into this than there is,” Judge Dennett says.

“Does Mia drink?” I ask.

“Not much,” Mrs. Dennett says.

“How do you know what Mia does, Eve? You two rarely speak.”

She puts her hand to her face to blot a runny nose and for a moment I am so taken aback by the size of the rock on her finger that I don’t hear James Dennett rambling on about how his wife had put in the call to Eddie—mind you, I’m struck here by the fact that not only is the judge on a first-name basis with my boss, but he’s also on a nickname basis—before he got home. Judge Dennett seems convinced that his daughter is out for a good time, and that there’s no need for any official involvement.

“You don’t think this is a case for the police?” I ask.

“Absolutely not. This is an issue for the family to handle.”

“How is Mia’s work ethic?”

“Excuse me?” the judge retorts as wrinkles form across his forehead and he rubs them away with an aggravated hand.

“Her work ethic. Does she have a good employment history? Has she ever skipped work before? Does she call in often, claim she’s sick when she’s not?”

“I don’t know. She has a job. She gets paid. She supports herself. I don’t ask questions.”

“Mrs. Dennett?”

“She loves her job. She just loves it. Teaching is what she always wanted to do.”

Mia is an art teacher. High school. I jot this down in my notes as a reminder.

The judge wants to know if I think that’s important. “Might be,” I respond.

“And why’s that?”

“Your Honor, I’m just trying to understand your daughter. Understand who she is. That’s all.”

Mrs. Dennett is now on the verge of tears. Her blue eyes begin to swell and redden as she pathetically attempts to suppress the tiny drips. “You think something has happened to Mia?”

I’m thinking to myself: isn’t that why you called me here? You think something has happened to Mia, but instead I say, “I think we act now and thank God later when this all turns out to be a big misunderstanding. I’m certain she’s fine, I am, but I’d hate to overlook this whole thing without at least looking into it.” I’d kick myself if—if—it turned out everything wasn’t fine.

“How long has Mia been living on her own?” I ask.

“It’ll be seven years in thirty days,” Mrs. Dennett states point-blank.

I’m taken aback. “You keep count? Down to the day?”

“It was her eighteenth birthday. She couldn’t wait to get out of here.”

“I won’t pry,” I say, but the truth is, I don’t have to. I can’t wait to get out of here, too. “Where does she live now?”

The judge responds. “An apartment in the city. Close to Clark and Addison.”

I’m an avid Chicago Cubs fan and so this is thrilling for me. Just mention the words Clark or Addison and my ears perk up like a hungry puppy. “Wrigleyville. That’s a nice neighborhood. Safe.”

“I’ll get you the address,” Mrs. Dennett offers.

“I would like to check it out, if you don’t mind. See if any windows are broken, signs of forced entry.”

Mrs. Dennett’s voice quavers as she asks, “You think someone broke into Mia’s apartment?”

I try to be reassuring. “I just want to check. Mrs. Dennett, does the building have a doorman?”

“No.”

“A security system? Cameras?”

“How are we supposed to know that?” the judge growls.

“Don’t you visit?” I ask before I can stop myself. I wait for an answer, but it doesn’t come.

Eve

After

I zip her coat for her and pull a hood over her head, and we walk out into the uncompromising Chicago wind. “We need to hurry now,” I say, and she nods though she doesn’t ask why. The gusts nearly knock us over as we make our way to James’s SUV, parked a half-dozen feet away, and as I reach for her elbow, the only thing I’m certain of is that if one of us falls, we are both going down. The parking lot is a sheet of ice four days after Christmas. I do my best to shield her from the cold and the relentless wind, pulling her into me and wrapping an arm around her waist to keep her warm, though my own petite figure is quite smaller than her own and I’m certain I fail miserably at the task.

“We go back next week,” I say to Mia as she climbs into the passenger seat, my voice loud over the clatter of doors slamming and seat belts locking. The radio shouts at us, the car’s engine on the verge of death on this bitter day. Mia flinches and I ask James to please turn the radio off. In the backseat, Mia is quiet, staring out the window and watching the cars, three of them, as they encircle us like a shiver of hungry sharks, their drivers meddlesome and ravenous. One lifts a camera to his eye and the flash all but blinds us.

“Where the hell are the cops when you need them?” James asks no one in particular, and then blares the horn until Mia’s hands rise up to cover her ears from the horrible sound. The cameras flash again. The cars loiter in the parking lot, their engines running, vivid smoke discharging from the exhaust pipes and into the gray day.

Mia looks up and sees me watching her. “Did you hear me, Mia?” I ask, my voice kind. She shakes her head, and I can all but hear the bothersome thought that runs through her mind: Chloe. My name is Chloe. Her blue eyes are glued to my own, which are red and watery from holding back tears, something that has become commonplace since Mia’s return, though as always James is there, reminding me to keep quiet. I try hard to make sense of it all, affixing a smile to my face, forced and yet entirely honest, and the unspoken words ramble through my mind: I just can’t believe you’re home. I’m careful to give Mia elbow room, not quite certain how much she needs, but absolutely certain I don’t want to overstep. I see her malady in every gesture and expression, in the way she stands, no longer brimming with self-confidence as the Mia I know used to be. I understand that something dreadful has happened to her.

I wonder, though, does she sense that something has happened to me?

Mia looks away. “We go back to see Dr. Rhodes next week,” I say and she nods in response. “Tuesday.”

“What time?” James asks.

“One o’clock.”

He consults his smartphone with a single hand, and then tells me that I will have to take Mia to the appointment alone. He says there is a trial, which he cannot miss. And besides, he says, he’s sure I can handle this alone. I tell him that of course I can handle it, but I lean in and whisper into his ear, “She needs you now. You’re her father.” I remind him that this is something we discussed and agreed to and how he promised. He says that he will see what he can do but the doubt weighs heavily on my mind. I can tell that he believes his unwavering work schedule does not allow time for family crises such as this.

In the backseat, Mia stares out the window watching the world fly by as we soar down I-94 and out of the city. It’s approaching three-thirty on a Friday afternoon, the weekend of the New Year, and so traffic is an ungodly mess. We come to a stop and wait and then inch forward at a snail’s pace, no more than thirty miles per hour on the expressway. James hasn’t the patience for it. He stares into the rearview mirror, waiting for the paparazzi to reappear.

“So, Mia,” James says, trying to pass the time. “That shrink says you have amnesia.”

“Oh, James,” I beg, “please, not now.”

My husband is not willing to wait. He wants to get to the bottom of this. It’s been barely a week since Mia has been home, living with James and me since she’s not fit to be on her own. I think of Christmas day, when the tired maroon car pulled sluggishly into the drive with Mia in tow. I remember the way James, nearly always detached, nearly always blasé, forced himself through the front door and was the first to greet her, to gather the emaciated woman in his arms on our snow-covered drive as if it had been him, rather than me, who spent those long, fearful months in mourning.

But since then, I’ve watched as that momentary relief shriveled away, as Mia, in her oblivion, became tiresome to James, just another one of the cases on his ever growing caseload rather than our daughter.

“Then when?”

“Later, please. And besides, that woman is a professional, James,” I insist. “A psychiatrist. She is not a shrink.”

“Fine then, Mia, that psychiatrist says you have amnesia,” he repeats, but Mia doesn’t respond. He watches her in the rearview mirror, these dark brown eyes that hold her captive. For a fleeting moment, she does her best to stare back, but then her eyes find their way to her hands, where she becomes absorbed in a small scab. “Do you wish to comment?” he asks.

“That’s what she told me, too,” she says, and I remember the doctor’s words as she sat across from James and me in the unhappy office—Mia having been excused and sent to the waiting room to browse through outdated fashion magazines—and gave us, verbatim, the textbook definition of acute stress disorder, and all I could think of were those poor Vietnam veterans.

He sighs. I can tell that James finds this implausible, the fact that her memory could vanish into thin air. “So, how does it work, then? You remember I’m your father and this is your mother, but you think your name is Chloe. You know how old you are and where you live and that you have a sister, but you don’t have a clue about Colin Thatcher? You honestly don’t know where you’ve been for the past three months?”

I jump in, to Mia’s defense, and say, “It’s called selective amnesia, James.”

“You’re telling me she picks and chooses things she wants to remember?”

“Mia doesn’t do it—her subconscious or unconscious or something like that is doing it. Putting painful thoughts where she can’t find them. It’s not something she’s decided to do. It’s her body’s way of helping her cope.”

“Cope with what?”

“The whole thing, James. Everything that happened.”

He wants to know how we fix it. This, I don’t know for certain, but I suggest, “Time, I suppose. Therapy. Drugs. Hypnosis.”

He scoffs at this, finding hypnosis as bona fide as amnesia. “What kind of drugs?”

“Antidepressants, James,” I respond. I turn around and, with a pat on Mia’s hand, say, “Maybe her memory will never come back and that will be okay, too.” I admire her for a moment, a near mirror image of myself, though taller and younger and, unlike me, years and years away from wrinkles and the white locks of hair that are beginning to intrude upon my mass of dirty blond.

“How will antidepressants help her remember?”

“They’ll make her feel better.”

He is always entirely candid. This is one of James’s flaws. “Well hell, Eve, if she can’t remember then what’s there to feel bad about?” he asks and our eyes stray out the windows at the passing traffic, the conversation considered through.

Gabe

Before

The high school where Mia Dennett teaches is located on the northwest side of Chicago in an area known as North Center. It’s a relatively good neighborhood, close to her home, a mostly Caucasian population with an average monthly rent over a thousand dollars. This all bodes well for her. If she was working in Englewood I wouldn’t be so sure. The purpose of the school is to provide an education to high school dropouts. They offer vocational training, computer training, life skills, et cetera, in small settings. Enter Mia Dennett, the art teacher, whose purpose is to add the nontraditional flair that’s been taken out of traditional high schools, those needing more time for math and science and to bore the hell out of sixteen-year-old misfits who couldn’t give a damn.

Ayanna Jackson meets me in the office. I have to wait a good fifteen minutes for her because she’s in the middle of class, and so I squeeze my body onto one of those small emasculating plastic school chairs and wait. This is something that certainly does not come easy to me. I’m far from the six-pack of my former days, though I like to think I wear the extra weight well. The secretary keeps her eyes locked on me the entire time as if I’m a student sent down to have a chat with the principal. This is a scene with which I’m sadly accustomed, many of my high school days spent in this very predicament.

“You’re trying to find Mia,” she says as I introduce myself as Detective Gabe Hoffman. I tell her that I am. It’s been nearly four days since anyone has seen or spoken to the woman and so she’s been officially designated as missing, much to the judge’s chagrin. It’s been in the papers, on the news, and every morning when I roll out of bed I tell myself that today will be the day I find Mia Dennett and become a hero.

“When’s the last time you saw Mia?”

“Tuesday.”

“Where?”

“Here.”

We make our way into the classroom and Ayanna—she begs me not to call her Ms. Jackson—invites me to sit down on one of those plastic chairs attached to the broken, graffiti-covered desk.

“How long have you known Mia?”

She sits at her desk in a comfy leather chair and I feel like a kid, though in reality, I top her by a good foot. She crosses her long legs, the slit of a black skirt falling open and exposing flesh. “Three years. As long as Mia’s been teaching.”

“Does Mia get along with everyone? The students? Staff?”

She’s solemn. “There’s no one Mia doesn’t get along with.”

Ayanna goes on to tell me about Mia. About how, when she first arrived at the alternative school, there was a natural grace about her, about how she empathized with the students and behaved as if she, too, had grown up on the streets of Chicago. About how Mia organized fundraisers for the school to pay for needy students’ supplies. “You never would have known she was a Dennett.”

According to Ms. Jackson, most new teachers don’t last long in this type of educational setting. With the market the way it is these days, sometimes an alternative school is the only place hiring and so college grads accept the position until something else comes along. But not Mia. “This was where she wanted to be.

“Let me show you something,” she says and she pulls a stack of papers from a letter tray on her desk. She walks closer and sits down on one of the student desks beside me. She sets the mound of paper before me and what I see first is a scribble of bad penmanship, worse than my own. “This morning the students worked on their journal entries for the week,” she explains and as my eyes peruse the work, I see the name Ms. Dennett more times than I can count.

“We do journal entries each week. The assignment this week,” she explains, “was to tell me what they wanted to do with themselves after high school.” I mull this over for a minute, seeing the words Ms. Dennett splattered over almost every sheet of paper. “But ninety-nine percent of the students are thinking of nothing but Mia,” she concludes, and I can hear, by the dejection in her voice, that she, too, can think of little but Mia.

“Did Mia have trouble with any of the students?” I ask, just to be sure. But I know what her answer is going to be before she shakes her head.

“What about a boyfriend?” I ask.

“I guess,” she says, “if you could call him that. Jason something-or-other. I don’t know his last name. Nothing serious. They’ve only been dating a few weeks, maybe a month, but no more.” I jot this down. The Dennetts made no reference to a boyfriend. Is it possible they don’t know? Of course it’s possible. With the Dennett family, I’m beginning to learn, anything is possible.

“Do you know how to get in touch with him?”

“He’s an architect,” she says. “Some firm off Wabash. She meets him there most Friday nights for happy hour. Wabash and...I don’t know, maybe Wacker? Somewhere along the river.” Sounds like a wild-goose chase to me, but I’m up for it. I make note of this information in my yellow pad.

The fact that Mia Dennett has an elusive boyfriend is great news for me. In cases like this, it’s always the boyfriend. Find Jason and I’m sure to find Mia as well, or what’s left of her. Considering she’s been gone for four days, I’m starting to think this story might have an unhappy ending. Jason works by the Chicago River: bad news. God knows how many bodies are pulled out of that river every year. He’s an architect, so he’s smart, good at solving problems, like how to discard a hundred-and-twenty-pound body without anyone noticing.

“If Mia and Jason were dating,” I ask, “is it odd that he isn’t trying to find her?”

“You think Jason might be involved?”

I shrug. “I know if I had a girlfriend and I hadn’t spoken to her in four days, I might be a little concerned.”

“I guess,” she agrees. She stands from the desk and begins to erase the chalkboard. It leaves tiny remnants of dust on her black skirt. “He didn’t call the Dennetts?”

“Mr. and Mrs. Dennett have no idea that there’s a boyfriend in the picture. As far as they’re concerned, Mia is single.”

“Mia and her parents aren’t close. They have certain...ideological differences.”

“I gather that.”

“I don’t think it’s the kind of thing she’d tell them.”

The topic is drifting, so I try to reel Ayanna back in. “You and Mia are close, though.” She says that they are. “Would you say that Mia tells you everything?”

“As far as I know.”

“What does she tell you about Jason?”

Ayanna sits back down, this time on the edge of her desk. She peers at a clock on the wall, dusts off her hands. She considers my question. “It wasn’t going to last,” she tells me, trying to find the right words to explain. “Mia doesn’t become involved too often, never anything serious. She doesn’t like to be tied down. Committed. She’s markedly independent, perhaps to a fault.”

“And Jason is...clingy? Needy?”

She shakes her head. “No, it’s not that, it’s just, he’s not the one. She didn’t glow when she spoke of him. She didn’t gossip like girls do when they’ve met the one. I always had to force her to tell me about him and then, it was like listening to a documentary: we went to dinner, we saw a movie.... And I know his hours were bad, which irritated Mia—he was always missing dates or showing up late. Mia hated to be tied down to his schedule. You have that many issues in the first month and it’s never going to last.”

“So it was possible Mia was planning to break up with him?”

“I don’t know.”

“But she wasn’t entirely happy.”

“I wouldn’t say Mia wasn’t happy,” Ayanna responds. “I just don’t think she cared one way or the other.”

“From what you know, did Jason feel the same?” She says that she doesn’t know. Mia was rather aloof when she spoke of Jason. The conversations were nondescript: a checklist of things they had done that day, details of the man’s statistics—height, weight, hair and eye color—though remarkably, no last name. But Mia never mentioned if they kissed and there was no reference to that tingly feeling in the pit of your stomach—Ayanna’s words, not mine—when you’ve met the man of your dreams. She seemed upset when Jason stood her up—which, by Ayanna’s account, happened often—and yet she didn’t seem particularly excited on the nights they planned a late-night rendezvous down by the Chicago River.

“And you’d characterize this as disinterest?” I ask. “In Jason? The relationship? The whole thing?”

“Mia was passing time until something better came along.”

“Did they fight?”

“Not that I know of.”

“But if there was a problem, Mia would have told you,” I suggest.

“I’d like to think she would have,” the woman responds, her dark eyes becoming sad.

A bell rings in the distance, followed by the clatter of footsteps in the hall. Ayanna Jackson rises to her feet, which I take as my cue. I say that I’ll be in touch and leave her with my card, asking that she call if anything comes to mind.

Eve

After

I’m halfway down the stairs when I see them, a news crew on the sidewalk before our home. They stand, shivering, with cameras and microphones; Tammy Palmer from the local news in a tan trench coat and knee-high boots on my front lawn. Her back is toward me, a man counting down on his fingers—three...two...—and as he points at Tammy I all but hear her broadcast begin. I’m standing here at the home of Mia Dennett....

This isn’t the first time they’ve been here. Their numbers have begun to dwindle now, their reporters moving onto other stories: same-sex marriage laws and the dismal state of the economy. But in the days after Mia’s return they were camped outside, desperate for a glimpse of the damaged woman, for any morsel of information to turn into a headline. They followed us around town in their cars until we all but locked Mia inside.

There have been mysterious cars parked outside, photographers for those trashy magazines peering out of car windows with their telephoto lenses, trying to turn Mia into a cash cow. I pull the drapes closed.

I spot Mia sitting at the kitchen table. I descend the stairs in silence, to watch my daughter in her own world before I intrude upon it. She’s dressed in a pair of ripped jeans and a snug navy turtleneck that I bet makes her eyes look just amazing. Her hair is damp from an earlier shower, drying in waves down her back. I’m addled by the thick wool socks that blanket her feet, that and the mug of coffee her hands are united around.

She hears me approach and turns to look. Yes, I think to myself, the turtleneck makes her eyes look amazing.

“You’re drinking coffee,” I say, and it’s the vague expression on her face that makes me certain I’ve said the wrong thing.

“I don’t drink coffee?”

I’ve been treading carefully for over a week now, always trying to say the right thing, going over-the-top—ridiculously so—to make her feel at home. I’ve been on edge to compensate for James’s apathy and Mia’s disarray. And then, when least expected, a seemingly benign conversation, and I slip up.

Mia doesn’t drink coffee. She doesn’t drink much caffeine at all. It makes her nervous. But I watch her sip from the mug, completely stagnant and sluggish, and think—wish—that maybe a little caffeine will do the trick. Who is this limp woman before me, I wonder, recognizing the face but having no knowledge of the body language or tone of voice or the disturbing silence that encompasses her like a bubble.

There are a million things I want to ask her. But I don’t. I’ve vowed to just let her be. James has pried more than enough for the both of us. I’ll leave the questions to the professionals, Dr. Rhodes and Detective Hoffman, and to those who just never know when to quit—James. She’s my daughter, but she’s not my daughter. She’s Mia, but she’s not Mia. She looks like her, but she wears socks and drinks coffee and wakes up sobbing in the middle of the night. She’s quicker to respond if I call her Chloe than when I call her by her given name. She looks empty, appears asleep when she’s awake, lies awake when she should be asleep. She nearly flew three feet from her seat when I turned on the garbage disposal last night and then retreated to her room. We didn’t see her for hours and when I asked how she passed the time all she could say was I don’t know. The Mia I know can’t sit still for that long.

“It looks like a nice day,” I offer but she doesn’t respond. It does look like a nice day; it’s sunny. But the sun in January is deceiving and I’m certain the earth will warm to no more than twenty degrees.

“I want to show you something,” I say and I lead her from the kitchen to the adjoining dining room, where I’ve replaced a limited edition print with one of Mia’s works of art, back in November when I was certain she was dead. Mia’s painting is done in oil pastels, this picturesque Tuscan village she drew from a photograph after we visited the area years ago. She layered the oil pastels, creating a dramatic representation of the village, a moment in time trapped behind this sheet of glass. I watch Mia eye the piece and think to myself: If only everything could be preserved that way. “You made that,” I say.

She knows. This she remembers. She recalls the day she set herself down at the dining room table with the oil pastels and the photograph. She had begged her father to purchase the poster-board for her and he agreed, though he was certain her newfound love of art was only a passing phase. When she was finished we all oohed and ahhed and then it was tucked away somewhere with old Halloween costumes and roller skates only to be stumbled upon later on a scavenger hunt for photographs of Mia that the detective asked us to collect.

“Do you remember our trip to Tuscany?” I ask.

She steps forward to run her lovely fingers over the work of art. She stands inches above me, but in the dining room she is a child—a fledgling not yet sure how to stand on her own two feet.

“It rained,” Mia responds without removing her eyes from the drawing.

I nod. “It did. It rained,” I say, glad that she remembered. But it rained only one day and the rest of the days were a godsend.

I want to tell her that I hung the drawing because I was so worried about her. I was terrified. I lay awake night after night for months on end just wondering, What if? What if she wasn’t okay? What if she was okay but we never found her? What if she was dead and we never knew? What if she was dead and we did know, the detective asking us to identify decaying remains?

I want to tell Mia that I hung her Christmas stocking just in case and that I bought her presents and wrapped them and put them under the tree. I want her to know that I left the porch light on every night and that I must have called her cell phone a thousand times just in case. Just in case one time it didn’t go straight to the voice mail. But I listened to the message over and over again, the same words, the same tone—Hi, this is Mia. Please leave a message—allowing myself to savor the sound of her voice for a while. I wondered: what if those were the last words I ever heard from my daughter? What if?

Her eyes are hollow, her expression vacant. She has the most unflawed peaches-and-cream complexion I believe I’ve ever seen, but the peaches seemed to have disappeared and now she is all cream, white as a ghost. She doesn’t look at me when we speak; she looks past me or through me, but never at me. She looks down much of the time, at her feet, her hands, anything to avoid another’s gaze.

And then, standing there in the dining room, her face drains of every last bit of color. It happens in an instant, the light seeping through the open drapes highlighting that way Mia’s body lurches upright and then sags at the shoulders, her hand falling from the image of Tuscany to her abdomen in one swift movement. Her chin drops to her chest, her breathing becomes hoarse. I lay a hand on her skinny—too skinny, I can feel bones—back and wait. But I don’t wait long; I’m impatient. “Mia, honey,” I say, but she’s already telling me that she’s okay, she’s fine, and I’m certain it’s the coffee.

“What happened?”

She shrugs. Her hand is glued to the abdomen and I know she doesn’t feel well. Her body has begun a retreat from the dining room. “I’m tired, that’s all. I just need to go lie down,” she says and I make a mental note to rid the house of all traces of caffeine before she wakes up from her nap.

Gabe

Before

“You’re not an easy man to find,” I say as he welcomes me into his work space. It’s more of a cubicle than an office, but with higher walls than normal, offering a minimal amount of privacy. There’s only one chair—his—and so I stand at the entrance to the cube, cocked at an angle against the pliable wall.

“I didn’t know someone was trying to find me.”

My first impression is he’s a pompous ass, much like myself years ago, before I realized I was more full of myself than I should be. He’s a big man, husky, though not necessarily tall. I’m certain he works out, drinks protein shakes, maybe uses steroids? I’ll jot this down in my notes, but for now, I’d hate to have him catch me making these assumptions. I might get my ass kicked.

“You know Mia Dennett?” I ask.

“That depends.” He turns around in his swivel chair, finishes typing an email with his back to me.

“On what?”

“On who wants to know.”

I’m not too eager to play this game. “I do,” I say, saving my trump card until later.

“And you are?”

“Looking for Mia Dennett,” I respond.

I can see myself in this guy, though he can barely be twenty-four or twenty-five years old, just out of college, still believing the world rotates around him. “If you say so.” I, however, am on the cusp of fifty, and just this morning noticed the first few strands of gray hair. I’m certain I have Judge Dennett to thank for them.

He continues the email. What the hell, I think. He couldn’t care less that I’m standing here, waiting to talk to him. I peer over his shoulder to have a look. It’s about college football, sent to a recipient by the user name dago82. My mother is Italian—hence the dark hair and eyes I’m certain all women are wooed by—and so I take the derogatory name as an insult against my people, though I’ve never been to Italy and don’t know a single word in Italian. I’m just looking for another reason not to like this guy. “Must be a busy day,” I comment and he seems peeved that I’m reading his email. He minimizes the screen.

“Who the hell are you?” he asks again.

I reach into my back pocket and pull out that shiny badge I adore so much. “Detective Gabe Hoffman.” He’s visibly knocked down a notch or two. I smile. God, do I love my job.

He plays dumb. “Is there a problem with Mia?”

“Yeah, I guess you can say that.”

He waits for me to continue. I don’t, just to piss him off. “What did she do?”

“When’s the last time you saw Mia?”

“It’s been a while. A week or so.”

“And the last time you spoke to her?”

“I don’t know. Last week. Tuesday night, I think.”

“You think?” I ask. He confirms on his calendar. Yes, it was Tuesday night. “But you didn’t see her Tuesday?”

“No. I was supposed to, but I had to cancel. You know, work.”

“Sure.”

“What happened to Mia?”

“So you haven’t spoken to her since Tuesday?”

“No.”

“Is that normal? To go nearly a week without speaking?”

“I called her,” he confesses. “Wednesday, maybe Thursday. She never called back. I just assumed she was pissed off.”

“And why would that be? Did she have a reason to be pissed off?”

He shrugs. He reaches for a bottle of water on the desk and takes a sip. “I canceled our date Tuesday night. I had to work. She was kind of short with me on the phone, you know? I could tell she was mad. But I had to work. So I thought she was holding a grudge and not calling back...I don’t know.”

“What were your plans?”

“Tuesday night?”

“Yeah.”

“Meet in a bar in Uptown. Mia was already there when I called. I was late. I told her I wasn’t going to make it.”

“And she was mad?”

“She wasn’t happy.”

“So you were here, working, Tuesday night?”

“Until like 3:00 a.m.”

“Anyone who can vouch for that?”

“Um, yeah. My boss. We were putting some designs together for a client meeting on Thursday. I met with her on and off half the night. Am I in trouble?”

“We’ll get to that,” I answer flatly, transcribing the conversation in my own shorthand that no one but me can decipher. “Where’d you go after you left work?”

“Home, man. It was the middle of the night.”

“You have an alibi?”

“An alibi?” He’s getting uncomfortable, squirming in his chair. “I don’t know. I took a cab home.”

“Get a receipt?”

“No.”

“You have a doorman in your building? Someone who can tell us you made it home safe?”

“Cameras,” he says, and then asks, “Where the fuck is Mia?”

I had pulled Mia’s phone records after my meeting with Ayanna Jackson. I found calls almost daily to a Jason Becker, who I tracked down to an architectural firm in the Chicago Loop. I paid this guy a visit to see what he knew about the girl’s disappearance, and saw the evident perception on his face when I said her name. “Yeah, I know Mia,” he said, leading me back to his cube. I saw it in the first instant: jealousy. He had himself convinced that I was the other guy.

“She’s missing,” I say, trying to read his response.

“Missing?”

“Yeah. Gone. No one has seen her since Tuesday.”

“And you think I had something to do with it?”

It irritates me that he’s more concerned with his culpability than Mia’s life. “Yeah,” I lie, “I think you might have something to do with it.” Though the truth is that if his alibi is as airtight as he’s making it out to be, I’m back to square one.

“Do I need a lawyer?”

“Do you think you need a lawyer?”

“I told you, I was working. I didn’t see Mia Tuesday night. Ask my boss.”

“I will,” I assure him, though the look that crosses his face begs me not to.

Jason’s co-workers eavesdrop on the interrogation. They walk slower as they pass his cube; they linger outside and pretend to carry on conversations. I don’t mind. He does. It’s driving him nuts. He’s worried about his reputation. I like to watch him squirm in his chair, becoming antsy. “Do you need anything else?” he asks to speed things along. He wants me out of his hair.

“I need to know your plans Tuesday night. Where Mia was when you called. What time it was. Check your phone records. I need to speak to your boss and make sure you were here, and with security to see what time you left. I’ll need the footage from your apartment cameras to verify you got home okay. If you’re comfortable providing me with that, then we’re all set. If you’d rather I get a warrant...”

“Are you threatening me?”

“No,” I lie, “just giving you your options.”

He agrees to provide me with the information I need, including an introduction to his boss, a middle-aged woman in an office ridiculously larger than his, with floor-to-ceiling windows that face out onto the Chicago River, before I leave.

“Jason,” I declare, after having been assured by the boss that he was working his ass off all night, “we’re going to do everything we can to find Mia,” just to see the expression of apathy on his face before I leave.

Colin

Before

It doesn’t take much. I pay off some guy to stay at work a couple hours later than he’d like to. I follow her to the bar and sit where I can watch her without being seen. I wait for the call to come and when she knows she’s been stood up, I move in.

I don’t know much about her. I’ve seen a snapshot. It’s a blurry photo of her stepping off the “L” platform, taken by a car parked a dozen or so feet away. There are about ten people between the photographer and the girl and so her face has been circled with a red pen. On the back of the photograph are the words Mia Dennett and an address. It was handed to me a week or so ago. I’ve never done anything like this before. Larceny, yes. Harassment, yes. Not kidnapping. But I need the money.

I’ve been following her for the last few days. I know where she buys her groceries, where she has her dry cleaning done, where she works. I’ve never spoken to her. I wouldn’t recognize the sound of her voice. I don’t know the color of her eyes or what they look like when she’s scared. But I will.

I carry a beer but I don’t drink it. I can’t risk getting drunk. Not tonight. But I don’t want to draw attention to myself and so I order the beer so I’m not empty-handed. She’s fed up when the call comes in on her cell phone. She steps outside to take the call and when she comes back she’s frustrated. She thinks about leaving, but decides to finish her drink. She finds a pen in her purse and doodles on a bar napkin, listening to some asshole read poetry on stage.

I try not to think about it. I try not to think about the fact that she’s pretty. I remind myself of the money. I need the money. This can’t be that hard. In a couple hours it will all be through.

“It’s good,” I say, nodding at the napkin. It’s the best I can come up with. I know nothing about art.

She gives me the cold shoulder when I first approach. She doesn’t want a thing to do with me. That makes it easier. She barely lifts her eyes from the napkin, even when I praise the candle she’s drawn. She wants me to leave her alone.

“Thanks.” She doesn’t look at me.

“Kind of abstract.”

This is apparently the wrong thing to say. “You think it looks like shit?”

Another man would laugh. He’d say he was kidding and kill her with compliments. But not me. Not with her.

I slide into the booth. Any other girl, any other day, I’d walk away. Any other day I wouldn’t have approached her table in the first place, not the table of some bitchy-looking, pissed-off girl. I leave small talk and flirting and all that other crap to someone else. “I didn’t say it looked like shit.”

She sets her hand on her coat. “I was about to leave,” she says. She swallows the rest of her drink and sets the glass on the table. “The booth is all yours.”

“Like Monet,” I say. “Monet does that abstract stuff, doesn’t he?”

I say it on purpose.

She looks at me. I’m sure it’s the first time. I smile. I wonder if what she sees is enough to lift her hand from the coat. Her tone softens and she knows she’s been abrupt. Maybe not so bitchy after all. Maybe just pissed off. “Monet is an impressionist painter,” she says. “Picasso, that’s abstract art. Kandinsky. Jackson Pollock.” I’ve never heard of them. She still plans to leave. I’m not worried. If she decides to leave, I’ll follow her home. I know where she lives. And I have plenty of time.

But I try anyway.

I reach for the napkin that she’s crumpled and set in an ashtray. I dust off the ashes and unfold it. “It doesn’t look like shit,” I say to her as I fold it and slide it into the back pocket of my jeans.

This is enough to send her eyes roving the bar for the waitress; she thinks she’ll have another drink. “You’re keeping that?” she asks.

“Yes.”

She laughs. “In case I’m famous one day?”

People like to feel as if they’re important. She lets it get the best of her.

She tells me that her name is Mia. I say that mine is Owen. I pause long enough when she asks my name for her to say, “I didn’t realize it was a hard question.” I tell her that my parents live in Toledo and that I’m a bank teller. None of it is the truth. She doesn’t offer much about herself. We talk about things that aren’t personal: a car crash on the Dan Ryan, a freight train derailing, the upcoming World Series. She suggests we talk about something that isn’t depressing. It’s hard to do. She orders one drink and then another. The more she drinks, the more open she becomes. She admits that her boyfriend stood her up. She tells me about him, that they’ve been dating since the end of August and she could count the number of dates he’s actually kept on one hand. She’s fishing for sympathy I don’t offer. It’s not me.

At some point I scoot closer to her in the booth. At times we touch, our legs brushing against one another without intent beneath the table.

I try not to think about it. About later. I try not to think about forcing her into the car or handing her over to Dalmar. I listen to her go on and on, about what, I don’t really know, because what I’m thinking about is the money. About how far cash like that will go. This—sitting with some lady in a bar I bet my life I’d never step foot in, taking hostages for ransom—isn’t my thing. But I smile when she looks at me, and when her hand touches mine, I let it stay because I know one thing: this girl might just change my life.

Eve

After

I’m looking through Mia’s baby book when it hits me: in second grade she had an imaginary friend named Chloe.

It’s there in the yellowing pages of the album, written in my own cursive in blue ink somewhere along the margin, sandwiched between a first broken bone and a wicked case of the flu that landed her in the emergency room. Her third-grade picture covers part of the name Chloe, but I can make it out.

I gaze at the third-grade picture, this portrait of a happy-go-lucky girl still years away from braces and acne and Colin Thatcher. She flashes this toothless grin with a mop of flaxen hair engulfing her head like flames. She’s splattered with freckles, something that has disappeared over time, and her hair is shades lighter than it will eventually be. The collar of her blouse is unfolded and I’m certain her scrawny legs are cloaked in a pair of hot pink leggings, likely a hand-me-down from Grace.

There are snapshots lining the pages of the baby book: Christmas morning when Mia was two and Grace seven, sporting their matching pajamas while James’s greasy hair stood on end. First days of school. Birthday parties.

I’m seated at the breakfast nook with the baby book spread open before me, eyeing cloth diapers and baby bottles and wanting it all back. I put in a call to Dr. Rhodes. To my surprise, she answers.

When I tell her about the imaginary friend, Dr. Rhodes takes off in psychological analysis. “Oftentimes, Mrs. Dennett, children create imaginary friends to compensate for loneliness or a lack of real friends in their lives. They often give these imaginary friends characteristics that they long for in their own lives, making them outgoing if the child is shy, for example, or a great athlete if a child is clumsy. Having an imaginary friend isn’t necessarily a physiological problem, assuming the friend disappears as the child matures.”

“Dr. Rhodes,” I respond, “Mia named her imaginary friend Chloe.”

She grows quiet. “That is interesting,” she says and I go numb.

I become obsessed with the name Chloe. I spend the morning on the internet trying to learn everything there is to know about this name. It’s a Greek name that means blooming...or blossoming or verdant or growth, depending on what website I search, but regardless, the words are synonymous with one another. This year it’s one of the more popular names, but back in 1990 it ranked 212th among all American baby names, slipped in between Alejandra and Marie. There are approximately 10,500 people in the United States right now with the name Chloe. Sometimes you find the name with an umlaut over the e (nearly twenty minutes is lost trying to find the meaning of those two dots over the vowel, and when I do—its purpose simply to differentiate between the o and e sounds at the end of the name—I realize it’s been a waste of time), sometimes without. I wonder how Mia spells it, though I won’t dare ask. Where would Mia have come up with a name like Chloe? Perhaps it was on the birth certificate of one of Mia’s prized Cabbage Patch Kids, flown in from Babyland General Hospital. I go to the website. I’m astounded to find new skin tones for this year’s babies—mocha and cream and latte—but no reference to a doll named Chloe. Maybe another child in Mia’s second-grade class...

I research famous people named Chloe: both Candice Bergen and Olivia Newton-John named their daughters Chloe. It’s the real first name of author Toni Morrison, though I highly doubt Mia was reading Beloved in the second grade. There’s Chloë Sevigney (with the umlaut) and Chloe Webb (without), though I’m certain the first is too young and the second too old for Mia to have paid any attention to when she was eight.

I could ask her. I could climb the steps and knock on the door of her bedroom and ask her. That’s what James would do. He’d get to the bottom of this. I want to get to the bottom of this, but I don’t want to violate Mia’s trust. Years ago I’d seek James’s advice, his help. But that was years ago.

I pick up the telephone, dial the numbers. The voice that greets me is kind, informal.

“Eve,” he says and I feel myself relax.

“Hello, Gabe.”

Colin

Before

I lead her to a high-rise apartment building on Kenmore. We take the elevator to the seventh floor. Loud music pours out of another apartment as we make our way down the piss-stained carpeting to a door at the end of the hall. I open the door as she stands by. It’s dark in the apartment. Only the stove light is on. I cross the parquet floors and flip on a lamp beside the sofa. The shadows disappear and are replaced with the contents of my meager living: Sports Illustrated magazines, a collection of shoes barricading the closet door, a half-eaten bagel on a paper plate on the coffee table. I watch silently as she judges me. It’s quiet. A neighbor has made Indian food tonight and the scent of curry chokes her.

“You okay?” she asks because she hates the uncomfortable silence. She’s probably thinking this was all a mistake, that she should leave.

I walk to her and run a hand down the length of her hair, grasping the strands at the base of her skull. I stare at her, placing her upon a pedestal, and see in her eyes how she wishes, if only for a moment, to stay there. It’s a place she hasn’t been for quite some time. She forgot how it felt to have someone stare that way. She kisses me and forgets altogether about leaving.

I press my lips against hers in a way that’s new and familiar all at the same time. My touch is assertive. I’ve done this a thousand times. It puts her at ease. If I were awkward, refusing to make the first move, she’d have time to reconsider. But as it is, it happens too fast.

And then, as quickly as it began, it’s over. I change my mind, pull away, and she asks, “What?” short of breath. “What’s wrong?” she begs, trying to pull me back to her. Her hands drop to my waistband, her drunken fingers clumsily work my belt.

“It’s a bad idea,” I say as I turn away from her.

“Why?” her voice begs. She grasps at my shirt in desperation. I move away, out of reach. And then, it sinks in slowly—the rejection. She’s embarrassed. She presses her hands to her face like she’s hot, clammy.

She drops onto the arm of a chair and tries to catch her breath. Around her, the room spins. I can see it in her expression: she isn’t used to hearing the word no. She rearranges a crumpled shirt, runs sweaty hands through her hair, ashamed.

I don’t know how long we stay like that.

“It’s just a bad idea,” I say then, suddenly inspired to pick up my shoes. I throw them in the closet, one pair at a time. They smack the back wall. They fall into a messy pile behind the closet door. And then I close the door, leaving the mess where I can’t see it.

And then the resentment creeps in and she asks, “Why did you bring me here? Why did you bring me here, if only to humiliate me?”

I picture us at the bar. I imagine my own greedy eyes when I leaned in and suggested, “Let’s get out of here.” I told her my apartment was just down the street. We all but ran the entire way.

I stare at her. “It’s not a good idea,” I say again. She stands and reaches for her purse. Someone passes in the hallway, their laughter like a thousand knives. She tries walking, loses her balance.

“Where are you going?” I ask, my body blocking the front door. She can’t leave now.

“Home,” she says.

“You’re wasted.”

“So?” she challenges. She reaches for the chair to steady herself.

“You can’t go,” I insist. Not when I’m this close, I think, but what I say is “Not like this.”

She smiles and says that’s sweet. She thinks I’m worried about her. Little does she know.

I couldn’t care less.

Gabe

After

Grace and Mia Dennett are sitting at my desk when I arrive, their backs turned in my direction. Grace couldn’t look more uncomfortable. She plucks a pen from my desk and removes the chewed-up cap with a sleeve of her shirt. I smooth a paisley tie against my shirt, and as I make my way to them, I hear Grace muttering the words “slovenly appearance” and “unbecoming” and “Spartan skin.” I assume she’s talking about me, and then I hear her say that Mia’s corkscrew locks haven’t seen a hair dryer in weeks; there are neglected bags beneath her eyes. Her clothes are rumpled and look like they should be cloaking the body of someone in junior high, a prepubescent boy no less. She doesn’t smile. “Ironic, isn’t it,” Grace says, “how I wish you’d snap at me—call me a bitch, a narcissist, any of those unpleasant nicknames you had for me in the days before Colin Thatcher.”

But instead Mia just stares.

“Good morning,” I say, and Grace interrupts me curtly with “Think we can get started? I have things to do today.”

“Of course,” I say, and then empty sugar packets into my coffee as slowly as I possibly can. “I was hoping to talk to Mia, see if I can get some information from her.”

“I don’t see how she can help,” Grace says. She reminds me of the amnesia. “She doesn’t remember what happened.”

I’ve asked Mia down this morning to see if we can jog her memory, see if Colin Thatcher told her anything inside that cabin that might be of value to the ongoing investigation. Since her mother wasn’t feeling well, she sent Grace in her place, as Mia’s chaperone, and I can see, in Grace’s eyes, that she’d rather be having dental work than sit here with Mia and me.

“I’d like to try and jog her memory. See if some pictures help.”

She rolls her eyes and says, “God, Detective, mug shots? We all know what Colin Thatcher looks like. We’ve seen the pictures. Mia has seen the pictures. Do you think she’s not going to identify him?”

“Not mug shots,” I assure her, reaching into a desk drawer to yank something from beneath a stash of legal pads. She peers around the desk to get the first glimpse and is stumped by the 11x14 sketch pad I produce. It’s a spiral-bound book; her eyes peruse the cover for clues, but the words recycled paper give nothing away. Mia, however, is briefly cognizant, of what neither she nor I know, but something passes through her—a wave of recollection—and then it’s gone as soon as it came. I see it in her body language—posture straightening, leaning forward, hands reaching out blindly for the pad, drawing it into her. “You recognize this?” I ask, voicing the words that were on the tip of Grace’s tongue.

Mia holds it in her hands. She doesn’t open it, but rather runs a hand over the textured cover. She doesn’t say anything and then, after a minute or so, she shakes her head. It’s gone. She slouches back into her chair and her fingers let go of the pad, allowing it to rest on her lap.

Grace snatches it from her. She opens the book and is greeted by an influx of Mia’s sketches. Eve told me once that Mia takes a sketch pad with her everywhere she goes, drawing anything from homeless men on the “L” to a car parked at the train station. It’s her way of keeping a journal: places she went, things she saw. Take this recycled sketch pad, for example: trees, and lots of them; a lake surrounded by trees; a homely little log cabin that, of course, we’ve all seen in the photos; a scrawny little tabby cat sleeping in a smattering of sun. None of this seems to surprise Grace, not until she comes to the illustration of Colin Thatcher that literally jumps off the page to greet her, snuck in the middle of the sketch pad amidst trees and the snow-covered cabin.

His appearance is bedraggled, his curly hair in complete disarray. The facial hair and tattered jeans and hooded sweatshirt surpass grunge and go straight to dirty. Mia had drawn a man, sturdy and tall. She applied herself to the eyes, shadowing and layering and darkening the pencil around them until these deep, leering headlights nearly force Grace to look away from the page.

“You drew this, you know,” she states, compelling Mia to have a look at the page. She thrusts it into her hands to see. He’s perched before a wood-burning stove, sitting cross-legged on the floor with his back to the flame. Mia runs her hand over the page and smudges the pencil a tad. She peers down at her fingertips and sees the remnants of lead, rubbing it between a thumb and forefinger.

“Does anything ring a bell?” I ask, sipping from my mug of coffee.

“Is this—” Mia hesitates “—him?”

“If by him you mean the creep who kidnapped you, then, yeah,” Grace says, “that’s him.”

I sigh. “That’s Colin Thatcher.” I show her a photograph. Not a mug shot, like she’s used to seeing, but a nice photo of him in his Sunday best. Mia’s eyes go back and forth, making the connection. The curly hair. The hardy build. The dark eyes. The bristly beige skin. The way his arms are crossed before him, his face appearing to do anything to conceal a smile. “You’re quite an artist,” I offer.

Mia asks, “And I drew this?”

I nod. “They found the sketch pad at the cabin with your and Colin’s things. I assume it belongs to you.”

“You brought it with you to Minnesota?” Grace asks.

Mia shrugs. Her eyes are locked on the images of Colin Thatcher. Of course she doesn’t know. Grace knows she doesn’t know, but she asks anyway. She’s thinking the same thing as me: here this creep is whisking her off to some abandoned cabin in Minnesota and she has the wherewithal to bring her sketch pad, of all things?

“What else did you bring?”

“I don’t know,” she says, her voice on the verge of being inaudible.

“Well, what else did you find?” Grace demands of me this time.

I watch Mia, recording her nonverbal communication: the way her fingers keep reaching out to touch the images before her, the frustration that is slowly, silently taking over. Every time she tries to give up and push the images away, she goes back to them, as if begging of her mind: think, just think. “Nothing out of the ordinary.”

Grace gets mad. “What does that mean? Clothes, food, weapons—guns, bombs, knives—an artists’ easel and a watercolor set? You ask me,” she says, pilfering the sketch pad from Mia’s hands, “this is out of the ordinary. A kidnapper doesn’t normally allow his abductee to draw the evidence on a cheap, recycled sketch pad.” She turns to Mia and presents the obvious. “If he sat still this long, Mia, long enough for you to draw this, then why didn’t you run?”

She stares at Grace with a stark expression on her face. Grace sighs, completely exasperated, and looks at Mia like she should be locked up in a loony ward. Like she has no grasp on reality, where she is or why she’s here. Like she wants to bang her over the head with a blunt object and knock some sense in her.

I come to her defense and say, “Maybe she was scared. Maybe there was nowhere to run. The cabin was in the middle of a vast wilderness, and northern Minnesota in the winter verges on a ghost town. There would have been nowhere to go. He might have found her, caught her and then what? Then what would have happened?”

Grace sulks into her chair and flips through the pages of the sketch pad, seeing the barren trees and the never-ending snow, this picturesque lake surrounded by dense woodland and...she nearly passes by it altogether and then flips back, ripping the page from its spiral binding, “Is that a Christmas tree?” she implores, gawking at the nostalgic image on the inner corner of a page. The tearing of the paper makes Mia leap from her seat.

I watch Mia startle and then lay a hand briefly on hers to put her at ease. “Oh, yeah,” I laugh, though there’s no amusement in it. “Yeah, I guess that would be considered out of the ordinary, wouldn’t it? We found a Christmas tree. Charming really, if you ask me.”

Colin

Before

She’s fighting the urge to fall asleep when the call comes in. She’s said about a thousand times that she needs to go. I’ve assured her that she doesn’t.

It took every bit of self-control to pull away from her. To turn my back to her pleading eyes and force myself to forget it. There’s just something wrong with screwing the girl you’re about to snatch.

But somehow or other I convinced her to stay. She thinks it’s for her own good. When she’s sober, I said, I’d walk her down for a cab. Apparently she bought it.

The phone rings. She doesn’t jump. She looks at me with the implication that it must be a girl. Who else would call in the middle of the night? It’s approaching 2:00 a.m. and as I move into the kitchen to take the call, I see her rise from the couch. She tries to fight the lethargy that’s taken over.

“Everything set?” Dalmar wants to know. I know nothing about Dalmar other than he just hopped off a boat and is blacker than anything I’ve ever seen. I’ve done jobs for Dalmar before: larceny and harassment. Never kidnapping.

“Un-huh.” I peek out at the girl who’s standing awkwardly in the living room. She’s waiting for me to finish up the call. Then she’ll split. I move away. I get as far away as I can. I carefully slide a semiautomatic from the drawer.

“Two-fifteen,” he says. I know where to meet: some dark corner of the underground where only homeless men wander at this time of night. I check my watch. I’m supposed to pull up behind a gray minivan. They grab the girl and leave the cash behind. That easy. I don’t even have to get out of the car.

“Two-fifteen,” I say. The Dennett girl is all but a hundred and twenty pounds. She’s lost in the midst of insobriety and a splitting headache. This will be easy.

She’s already saying that she’s gonna go when I come back into the living room. She’s headed to the front door. I stop her with a single arm around her waist. I draw her away from the door, my arm touching flesh. “You’re not going anywhere.”

“No, really,” she says. “I have to work in the morning.”

She giggles. Like maybe this is funny. Some kind of come-on.

But there’s the gun. She sees it. And in that moment, things change. There’s a moment of recognition. Of her mind registering the gun, of her figuring out what the fuck is about to happen. Her mouth parts and out comes a word: “Oh.” And it’s almost an afterthought, really, when she sees the gun and says, “What are you doing with that?” She backs away from me, bumping into the couch.

“You need to come with me.” I step forward, closing the gap.

“Where?” she asks. When my hands come down on her, she jerks away. I unknot the arms and reel her in.

“Don’t make this harder than it has to be.”

“What are you doing with that gun?” she snaps. She’s calmer than I expect her to be. She’s concerned. But not screaming. Not crying. She’s got her eyes bound to the gun.

“You just need to come with me.” I reach out and grasp her arm. She’s trembling. She slips away. But I hold her tight, twisting her arm. She cries out in pain. She shoots me a dirty look—hurt and unexpected. She tells me to let go, to keep my hands off her. There’s a superiority in her voice that pisses me off. Like she’s the one running this show.

She tries to rip free but finds she can’t. I won’t let her.