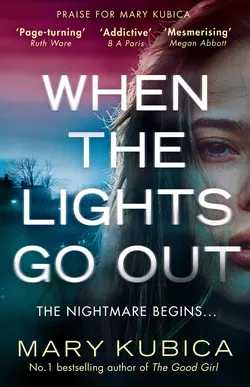

When The Lights Go Out: The addictive new thriller from the bestselling author of The Good Girl

Mary Kubica

‘Creepy and oh so clever, with a brilliant twist I did not see coming!’ ALICE FEENEY‘A captivating edge-of-your-seat read.’ MEGAN MIRANDAMary Kubica is back with a bang in this compulsively gripping tale of obsession and desperation.***As far as the world’s concerned, she’s already deadJessie Sloane is getting her life back on track after caring for her sick mother. But she’s stopped short when she discovers, that according to official records, ‘Jessie Sloane’ died seventeen years ago.So why does she still feel in danger? Thrown into turmoil and questioning everything she’s ever known, Jessie’s confusion is exacerbated by a relentless lack of sleep. Stuck in a waking nightmare and convinced she’s in danger, she can no longer tell what’s real and what she’s imagined.The truth lies in the past…Twenty years ago, another woman’s split-second decision may hold the key to Jessie’s secret history. Has her whole life been a lie? The truth will shock her to the core…if she lives long enough to discover it.Why readers love Mary Kubica:‘One of the very best thrillers I’ve read – ever.’‘Kept me guessing the whole way through. Sheer genius.’‘Messed with my mind (in a good way). I want more!’‘Totally riveting and all-consuming’‘The ending is a real twist of the knife – it doesn’t get much better than this.’‘A very fast paced story which keeps you guessing till the end and what a twist!’‘Omg! This is one of the best books that I have ever read! Great thriller, love it!’

A woman is forced to question her own identity in this riveting and emotionally charged thriller by the blockbuster bestselling author of The Good Girl, Mary Kubica

Jessie Sloane is on the path to rebuilding her life after years of caring for her ailing mother. She rents a new apartment and applies for college. But when the college informs her that her social security number has raised a red flag, Jessie discovers a shocking detail that causes her to doubt everything she’s ever known.

Finding herself suddenly at the center of a bizarre mystery, Jessie tumbles down a rabbit hole, which is only exacerbated by grief and a relentless lack of sleep. As days pass and the insomnia worsens, it plays with Jessie’s mind. Her judgment is blurred, her thoughts are hampered by fatigue. Jessie begins to see things until she can no longer tell the difference between what’s real and what she’s only imagined.

Meanwhile, twenty years earlier and two hundred and fifty miles away, another woman’s split-second decision may hold the key to Jessie’s secret past. Has Jessie’s whole life been a lie or have her delusions gotten the best of her?

MARY KUBICA holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in History and American Literature from Miami University in Oxford, Ohio. She lives near Chicago with her husband and two children.

Also by Mary Kubica (#u298352a8-6366-5809-abab-2dbb2eb6f5bc)

The Good Girl

Pretty Baby

Don’t You Cry

Every Last Lie

Copyright (#u298352a8-6366-5809-abab-2dbb2eb6f5bc)

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2018

Copyright © Mary Kyrychenko 2018

Mary Kyrychenko asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © August 2018 ISBN: 9781474057622

Praise for Mary Kubica (#u298352a8-6366-5809-abab-2dbb2eb6f5bc)

‘Brilliant, intense, and utterly addictive. Be prepared to run a gauntlet of emotions!’

B A Paris

‘Grabs you from the moment it starts’

Daily Mail

‘Gets right under your skin and leaves its mark. A tremendous read’

The Sun

‘Sensational’

Metro

‘Perfect suspense’

BuzzFeed

‘Fans of Gone Girl will embrace this’

Lisa Gardner

‘An utterly mesmerising tale of marriage and secrets… it’ll have you rapt until its final pages’

Megan Abbott

‘Single White Female on steroids’

Lisa Scottoline

For

Dick & Eloise

Rudy & Myrtle

Contents

Cover (#ue076ce60-1bf5-5f2c-b045-75906a310f8c)

Back Cover Text (#ua863adec-f5b4-5ef1-8c8f-94ce3f77d112)

About the Author (#uff92868e-d172-5ddb-8372-31c99f2cda60)

Booklist (#ua5ee61d3-91cc-5154-ace5-76356ef02f9c)

Title Page (#u158142d1-ef67-5ac7-a3ce-eeaf00bcbdbf)

Copyright (#u07bce27a-28d3-55a8-9be3-bf6057f62575)

Praise (#ubdf2a732-f26e-51b8-840b-627a94fb68ac)

Dedication (#ub54fcd9d-9d68-5cfc-81df-83d427dd3d3c)

prologue (#ua2f52e87-c490-56fd-9f79-6c03bc62d44f)

jessie (#u4c555a3d-f740-56ce-be5d-adfbdf8c65e8)

eden (#u7e79cc18-da90-5656-8093-4eed9ec1c2ad)

jessie (#udc55183c-ed71-5809-8b64-f94949c892b8)

eden (#ucf724d9f-5815-5c56-af60-1607b43c3f81)

jessie (#u7fa41f4f-fec7-5915-bee1-c75528979895)

eden (#uc783e266-844b-5076-90e9-407d84a36bb9)

jessie (#u8a81de3a-d2c9-55a5-a7c3-68c0da87bfe0)

eden (#u7f141315-1356-55b2-909c-99099e8fb624)

jessie (#u291fba67-6762-52a0-b609-3ca7f1d5cebf)

eden (#litres_trial_promo)

jessie (#litres_trial_promo)

eden (#litres_trial_promo)

jessie (#litres_trial_promo)

eden (#litres_trial_promo)

jessie (#litres_trial_promo)

eden (#litres_trial_promo)

jessie (#litres_trial_promo)

eden (#litres_trial_promo)

jessie (#litres_trial_promo)

eden (#litres_trial_promo)

jessie (#litres_trial_promo)

eden (#litres_trial_promo)

jessie (#litres_trial_promo)

eden (#litres_trial_promo)

jessie (#litres_trial_promo)

eden (#litres_trial_promo)

jessie (#litres_trial_promo)

eden (#litres_trial_promo)

jessie (#litres_trial_promo)

eden (#litres_trial_promo)

jessie (#litres_trial_promo)

eden (#litres_trial_promo)

jessie (#litres_trial_promo)

eden (#litres_trial_promo)

eden (#litres_trial_promo)

jessie (#litres_trial_promo)

eden (#litres_trial_promo)

jessie (#litres_trial_promo)

eden (#litres_trial_promo)

acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

prologue (#u298352a8-6366-5809-abab-2dbb2eb6f5bc)

The city surrounds me. A panorama. With arms outstretched, I can’t help but spin, taking it all in. Enjoying the view, knowing fully well this may be the last thing my eyes ever see.

I stare at the four metal steps before me, aware of how frail and broken-down they look. They’re orange with rust, paint flaking, some of the slats loose so that when I press my foot to the first step, it buckles beneath me and I fall.

Still, I have no choice but to climb.

I pull myself back up, set my hands on the rails and scale the steps. The sweat bleeds from my palms so that the metal beneath them is slippery, slick. I can’t hold tight. I slip from the second step, try again. I call out, voice cracking, a voice that doesn’t sound like mine.

As I reach the roof’s ledge, my knees give. It takes everything I have not to topple over the edge of the building and onto the street below. Seventeen floors.

I’m so high I could touch the clouds, I think. The sense of vertigo is overpowering. The ground whooshes up and at me, the skyscrapers, the trees starting to sway until I no longer know what’s moving: them or me. Little yellow matchbooks soar up and down the city streets. Cabs.

If I was standing at street level, the ledge would feel plenty wide. But up here it’s not. Up here it’s a thread and on it, I’m trying to balance my two wobbly feet.

I’m scared. But I’ve come this far. I can’t go back.

There’s a moment of calm that comes and goes so quickly I almost don’t notice it. For one split second the world is still. I’m at peace. The sun moves higher and higher into the sky, yellow-orange glaring at me through the buildings, making me peaceful and warm. My hands rise beside me as a bird goes soaring by. As if my hands are wings, I think in that moment what it would be like to fly.

And then it comes rushing back to me.

I’m hopelessly alone. Everything hurts. I can no longer think straight; I can no longer see straight; I can no longer speak. I don’t know who I am anymore. If I am anyone.

And I know in that moment for certain: I am no one.

I think what it would feel like to fall. The weightlessness of the plunge, of gravity taking over, of relinquishing control. Giving up, surrendering to the universe.

There’s a flicker of movement beneath me. A flash of brown, and I know that if I wait any longer, it will be too late. The decision will no longer be mine. I cry out one more time.

And then I go.

jessie (#u298352a8-6366-5809-abab-2dbb2eb6f5bc)

I don’t have to see myself to know what I look like.

My eyes are fat and bloated, so bloodshot the sclera is bereft of white. The skin around them is red and raw from rubbing. They’ve been like this for days. Ever since Mom’s body began shutting down, her hands and feet cold, blood no longer circulating there. Since she began to drift in and out of consciousness, refusing to eat. Since she became delirious, speaking of things that aren’t real.

Over the last few days, her breathing has changed too, becoming noisier and unstable, developing what the doctor called Cheyne-Stokes respiration where, for many seconds at a time, she didn’t breathe. Short, shallow breaths followed by no breaths at all. When she didn’t breathe, I didn’t breathe. Her nails are blue now, the skin of her arms and legs blotchy and gray. “It’s a sign of imminent death,”the doctor said only yesterday as he set a firm hand on my shoulder and asked if there was someone they could call, someone who could come sit with me until she passed.

“It won’t be long now,” he’d said.

I had shaken my head, refusing to cry. It wasn’t like me to cry. I’ve sat in the same armchair for nearly a week now, in the same rumpled clothes, leaving only to collect coffee from the hospital cafeteria. “There’s no one,” I said to the doctor. “It’s only Mom and me.”

Only Mom and me as it’s always been. If I have a father somewhere out there in the world, I don’t know a thing about him. Mom didn’t want me to know anything about him.

And now this evening, Mom’s doctor stands before me again, taking in my bloated eyes, staring at me in concern. This time offering up a pill. He tells me to take it, to go lie down in the empty bed beside Mom’s and sleep.

“When’s the last time you’ve slept, Jessie?” he asks, standing there in his starch white smock, tacking on, “I mean, really slept,” before I can lie. Before I can claim that I slept last night. Because I did, for a whole thirty minutes, at best.

He tells me the longest anyone has gone without sleep. He tells me that people can die without sleep. He says to me, “Sleep deprivation is a serious matter. You need to sleep,” though he’s not my doctor but Mom’s. I don’t know why he cares.

But for whatever reason, he goes on to list for me the consequences of not sleeping. Emotional instability. Crying and laughing for no sound reason at all. Behaving erratically. Losing concept of time. Seeing things. Hallucinating. Losing the ability to speak.

And then there are the physical effects of insomnia: heart attack, hypothermia, stroke.

“Sleeping pills don’t work for me,” I tell him, but he shakes his head, tells me that it’s not a sleeping pill. Rather a tranquilizer of some sort, used for anxiety and seizures. “It has a sedative effect,” he says. “Calming. It will help you sleep without all the ugly side effects of a sleeping pill.”

But I don’t need to sleep. What I need instead is to stay awake, to be with Mom until she makes the decision to leave.

I push myself from my chair, strut past the doctor standing in the doorway. “Jessie,” he says, a hand falling gently to my arm to try and stop me before I can go. His smile is fake.

“I don’t need a pill,” I tell him briskly, plucking my arm away. My eyes catch sight of the nurse standing in the hallway beside the nurses’ station, her eyes conveying only one thing: pity. “What I need is coffee,” I say, not meeting her eye as I slog down the hallway, feet heavy with fatigue.

* * *

There’s a guy I see in the cafeteria every now and then, a little bit like me. A weak frame lost inside crumpled-up clothes; tired, red eyes but doped up on caffeine. Like me, he’s twitchy. On edge. He has a square face; dark, shaggy hair; and thick eyebrows that are sometimes hidden behind a pair of sunglasses so that the rest of us can’t see he’s been crying. He sits in the cafeteria with his feet perched on a plastic chair, a red sweatshirt hood pulled over his head, sipping his coffee.

I’ve never talked to him before. I’m not the kind of girl that cute guys talk to.

But tonight, for whatever reason, after I get my cup of coffee, I drop down into the chair beside him, knowing that under any other circumstance, I wouldn’t have the nerve to do it. To talk to him. But tonight I do, mostly, I think, to delay going back to Mom’s room, to give the doctor his chance to examine her and leave.

“Want to talk about it?” I ask, and at first his look is surprised. Incredulous, even. His gaze rises up from his own coffee cup and he stares at me, his eyes as blue as a blue morpho butterfly’s wings.

“The coffee,” he says after some time, pushing his cup away. “It tastes like shit,” he tells me, as though that’s the thing that’s bothering him. The only thing. Though I see well enough inside the cup to know that he drank it down to the dregs, so it couldn’t have been that bad.

“What’s wrong with it?” I ask, sipping from my cup. It’s hot and so I peel back the plastic lid and blow on it. Steam rises to greet me as I try again and take another sip. This time, I don’t burn my mouth.

There’s nothing wrong with the hospital’s coffee. It’s just the way I like it. Nothing fancy. Just plain old coffee. But still, I dump four packets of Equal in and swirl it around because I don’t have a stir stick or spoon.

“It’s weak and there are grounds in it,” he tells me, giving his abandoned cup the stink eye. “I don’t know,” he says, shrugging. “Guess I just like my coffee stronger than this.”

And yet, he reaches again for the cup before remembering there’s nothing left in it.

There’s an anger in his demeanor. A sadness. It doesn’t have anything to do with the coffee. He just needs something to take his anger out on. I see it in his blue eyes, how he wishes he was somewhere else, anywhere else but here.

I too want to be anywhere else but here.

“My mother’s dying,” I tell him, looking away because I can’t stand to stare into his eyes when I say the words aloud. Instead I gaze toward a window where outside the world has gone black. “She’s going to die.”

Silence follows. Not an awkward silence, but just silence. He doesn’t say he’s sorry because he knows, like me, that sorry doesn’t mean a thing. Instead, after a minute or two, he says that his brother’s been in a motorcycle accident. That a car cut him off and he went flying off the bike, headfirst, into a utility pole.

“There’s no saying if he’ll make it,” he says, talking in euphemisms because it’s easier that way than just saying there’s a chance he’ll die. Kick the bucket. Croak. “Odds are good we’ll have to pull the plug sometime soon. The brain damage.” He shakes his head, picks at the skin around his fingernails. “It’s not looking good,” he tells me, and I say, “That sucks,” because it does.

I rub at my eyes and he changes topics. “You look tired,” he tells me, and I admit that I can’t sleep. That I haven’t been sleeping. Not for more than thirty minutes at a time, and even that’s being generous. “But it’s fine,” I say, because my lack of sleep is the least of my concerns.

He knows what I’m thinking.

“There’s nothing more you can do for your mom,” he says. “Now you’ve got to take care of you. You’ve got to be ready for what comes next. You ever try melatonin?” he asks, but I shake my head and tell him the same thing I told Mom’s doctor.

“Sleeping pills don’t work for me.”

“It’s not a sleeping pill,” he says as he reaches into his jeans pocket and pulls out a handful of pills. He slips two tablets into the palm of my hand. “It’ll help,” he says to me, but any idiot can see that his own eyes are bloodshot and tired. It’s obvious this melatonin didn’t help him worth shit. But I don’t want to be rude. I slip the tablets into the pocket of my own jeans and say thanks.

He stands from the table, chair skidding out from beneath him, and says he’ll be right back. I think that it’s an excuse and that he’s going to take the opportunity to split. “Sure thing,” I say, looking the other way as he leaves. Trying not to feel sorry for myself as I’m hit with that sudden sense of being alone. Trying not to think about my future, knowing that when Mom finally dies, I’ll be alone forever.

He’s gone now and I watch other people in the cafeteria. New grandparents. A group of people sitting at a round table, laughing. Talking about old times, sharing memories. Some sort of hospital technician in blue scrubs eating alone. I reach for my now-empty cup of coffee, thinking that I too should split. Knowing that the doctor is no doubt done with Mom by now, and so I should get back to her.

But then the guy comes back. In his hands are two fresh cups of coffee. He returns to his chair and states the obvious. “Caffeine is the last thing either of us needs,” he tells me, saying that it’s decaf, and it occurs to me then that this has nothing to do with the coffee, but rather the company.

He digs into his pocket and pulls out four rumpled packets of Equal, dropping them to the table beside my cup. I manage a thanks, flat and mumbled to hide my surprise. He was watching me. He was paying attention. No one ever pays attention to me, aside from Mom.

Beside me he hoists his feet back onto the empty seat across from him, crosses them at the ankles. Drapes the red hood over his head.

I wonder what he’d be doing right now if he wasn’t here. If his brother hadn’t been in that motorcycle accident. If he wasn’t close to dying.

I think that if he had a girlfriend, she’d be here, holding his hand, keeping him company. Wouldn’t she?

I tell him things. Things I’ve never told anyone else. I don’t know why. Things about Mom. He doesn’t look at me as I talk, but at some imaginary spot on the wall. But I know he’s listening.

He tells me things too, about his brother, and for the first time in a while, I think how nice it is to have someone to talk to, or to just share a table with as the conversation in time drifts to quiet and we sit together, drinking our coffees in silence.

* * *

Later, after I return to Mom’s room, I think about him. The guy from the cafeteria. After the hospital’s hallway lights are dimmed and all is quiet—well, mostly quiet save for the ping of the EKG in Mom’s room and the rattle of saliva in the back of her throat since she can no longer swallow—I think about him sitting beside his dying brother, also unable to sleep.

In the hospital, Mom sleeps beside me in a drug-induced daze, thanks to the steady drip, drip, drip of lorazepam and morphine into her veins, a solution that keeps her both pain-free and fast asleep at the same time.

Sometime after nine o’clock, the nurse stops by to turn Mom one last time before signing off for the night. She checks her skin for bedsores, running a hand up and down Mom’s legs. I’ve got the TV in the room turned on, anything to drown out that mechanical, metallic sound of Mom’s EKG, one that will haunt me for the rest of my life. It’s one of those newsmagazine shows—Dateline, 60 Minutes, I don’t know which—the one thing that was on when I flipped on the TV. I didn’t bother channel surfing; I don’t care what I watch. It could be home shopping or cartoons, for all I care. It’s just the noise I need to help me forget that Mom is dying. Though, of course, it isn’t as easy as that. There isn’t a thing in the world that can make me forget. But for a few minutes at least, the news anchors make me feel less alone.

“What are you watching?” the nurse asks, examining Mom’s skin, and I say, “I don’t even know.”

But then we both listen together as the anchors tell the story of some guy who’d assumed the identity of a dead man. He lived for years posing as him, until he got caught.

Leave it to me to watch a show about dead people as a means of forgetting that Mom is dying.

My eyes veer away from the TV and to Mom. I mute the show. Maybe the repetitive ping of the EKG isn’t so bad after all. What it says to me is that Mom is still alive. For now.

Ulcers have already formed on her heels and so she lies with feet floating on air, a pillow beneath her calves so they can’t touch the bed. “Feeling tired?” the nurse asks, standing in the space between Mom and me. I am, of course, feeling tired. My head hurts, one of those dull headaches that creeps up the nape of the neck. There’s a stinging pain behind my eyes too, the kind that makes everything blur. I dig my palms into my sockets to make it go away, but it doesn’t quit. My muscles ache, my legs restless. There’s the constant urge to move them, to not sit still. It gnaws at me until it’s all I can think about: moving my legs. I uncross them, stretch them out before me, recross my legs. For a whole thirty seconds it works. The restlessness stops.

And then it begins again. That prickly urge to move my legs.

If I let it, it’ll go on all night until, like last night, when I finally stood and paced the room. All night long. Because it was easier than sitting still.

I think then about what the guy in the cafeteria said. About taking care of myself, about getting ready for what comes next. I think about what comes next, about Mom’s and my house, vacant but for me. I wonder if I’ll ever sleep again.

“Doc left some clonazepam for you,” the nurse says now, as if she knows what I’m thinking. “In case you changed your mind.” She says that it could be our little secret, hers and mine. She tells me Mom is in good hands. That I need to take care of myself now, again just like the guy in the cafeteria said.

I relent. If only to make my legs relax. She steps from the room to retrieve the pills. When she returns, I climb onto the empty bed beside Mom and swallow a single clonazepam with a glass of water and sink beneath the covers of the hospital bed. The nurse stays in the room, watching me. She doesn’t leave.

“I’m sure you have better things to do than keep me company,” I tell her, but she says she doesn’t.

“I lost my daughter a long time ago,” she says, “and my husband’s gone. There’s no one at home waiting for me. None other than the cat. If it’s all right with you, I’d rather just stay. We can keep each other company, if you don’t mind,” she says, and I tell her I don’t mind.

There’s an unearthly quality to her, ghostlike, as if maybe she’s one of Mom’s friends from her dying delusions, come to visit me. Mom had begun to talk to them the last time she was awake, people in the room who weren’t in the room, but who were already dead. It was as if Mom’s mind had already crossed over to the other side.

The nurse’s smile is kind. Not a pity smile, but authentic. “The waiting is the hardest part,” she tells me, and I don’t know what she means by it—waiting for the pill to kick in or waiting for Mom to die.

I read something once about something called terminal lucidity. I didn’t know if it’s real or not, a fact—scientifically proven—or just some superstition a quack thought up. But I’m hoping it’s real. Terminal lucidity: a final moment of lucidity before a person dies. A final surge of brainpower and awareness. Where they stir from a coma and speak one last time. Or when an Alzheimer’s patient who’s so far gone he doesn’t know his own wife anymore wakes up suddenly and remembers. People who have been catatonic for decades get up and for a few moments, they’re normal. All is good.

Except that it’s not.

It doesn’t last long, that period of lucidity. Five minutes, maybe more, maybe less. No one knows for sure. It doesn’t happen for everyone.

But deep inside I’m hoping for five more lucid moments with Mom.

For her to sit up, for her to speak.

“I’m not tired yet,”I confess to the nurse after a few minutes, sure this is a waste of time. I can’t sleep. I won’t sleep. The restlessness of my legs is persistent, until I have no choice but to dig the melatonin out of my pocket when the nurse turns her back and swallow those too.

The hospital bed is pitted, the blankets abrasive. I’m cold. Beside me, Mom’s breathing is dry and uneven, her mouth gaping open like a robin hatchling. Scabs have formed around her lips. She jerks and twitches in her sleep. “What’s happening?” I ask the nurse, and she tells me Mom is dreaming.

“Bad dreams?” I ask, worried that nightmares might torment her sleep.

“I can’t say for sure,” the nurse says. She repositions Mom on her right side, tucking a rolled-up blanket beneath her hip, checking the color of her hands and feet. “No one even knows for sure why we dream,” the nurse tells me, adding an extra blanket to my bed in case I catch a draft in my sleep. “Did you know that?” she asks, but I shake my head and tell her no. “Some people think that dreams serve no purpose,” she adds, winking. “But I think they do. They’re the mind’s way of coping, of thinking through a problem. Things we saw, felt, heard. What we’re worried about. What we want to achieve. You want to know what I think?” she asks, and without waiting for me to answer, she says, “I think your mom is getting ready to go in that dream of hers. Packing her bags and saying goodbye. Finding her purse and her keys.”

I can’t remember the last time I’d dreamed.

“It can take up to an hour to kick in,”the nurse says, and this time I know she means the medicine.

The nurse catches me staring at Mom. “You can talk to her, you know?” she asks. “She can hear you,” she says, but it’s awkward then. Talking to Mom while the nurse is in the room. And anyway, I’m not convinced that Mom can really hear me, so I say to the nurse, “I know,” but to Mom, I say nothing. I’ll say all the things I need to say if we’re ever alone. The nurses play Mom’s records some of the time because, as they’ve told me, hearing is the last thing to go. The last of the senses to leave. And because they think it might put her at ease, as if the soulful voice of Gladys Knight & the Pips can penetrate the state of unconsciousness where she’s at, and become part of her dreams. The familiar sound of her music, those records I used to hate when I was a kid but now know I’ll spend the rest of my life listening to on repeat.

“This must be hard on you,” the nurse says, watching me as I stare mournfully at Mom, taking in the shape of her face, her eyes, for what might be the last time. Then she confesses, “I know what it’s like to lose someone you love.” I don’t ask the nurse who, but she tells me anyway, admitting to the little girl she lost nearly two decades ago. Her daughter, only three years old when she died. “We were on vacation,” she says. “My husband and me with our little girl.” He’s her ex-husband now because, as she tells me, their marriage died that day too, same day as their little girl. She tells me how there was nothing Madison loved more than playing in the sand, searching for seashells along the seashore. They’d taken her to the beach that summer. “My last good memories are of the three of us at the beach. I still see her sometimes when I close my eyes. Even after all these years. Bent at the waist in her purple swimsuit, digging fat fingers into the sand for seashells. Funny thing is that I have a hard time remembering her face, but clear as day I see the ruffles of that purple tulle skirt moving in the air.”

I don’t know what to say. I know I should say something, something empathetic. I should commiserate. But instead I ask, “How did she die?” because I can’t help myself. I want to know, and there’s a part of me convinced she wants me to ask.

“A hit-and-run,” she admits while dropping into an empty armchair in the corner of the room. Same one that I’ve spent the last few days in. She tells me how the girl wandered into the street when she and her husband weren’t paying attention. It was a four-lane road with a speed limit of just twenty-five as it twisted through the small seaside town. The driver rounded a bend at nearly twice that speed, not seeing the little girl before he hit her, before he fled.

“He,” she says then. “He.” And this time, she laughs, a jaded laugh. “I’ll never know one way or the other if the driver was male or female, but to me it’s always been he because for the life of me I can’t see a woman running her car into a child and then fleeing. It goes against our every instinct, to nurture, to protect,” she says.

“It’s so easy to blame someone else. My husband, the driver of the car. Even Madison herself. But the truth is that it was my fault. I was the one not paying attention. I was the one who let my little girl waddle off into the middle of the street.”

And then she shakes her head with the weariness of someone who’s replayed the same scene in her life for many years, trying to pinpoint the moment when it all went wrong. When Madison’s hand slipped from hers, when she fell from view.

I don’t mean for them to, but still, my eyes fill with tears as I picture her little girl in her purple swimsuit, lying in the middle of the road. One minute gathering seashells in the palm of a hand, and the next minute dead. It seems so tragic, so catastrophic, that my own tragedy somehow pales in comparison to hers. Suddenly cancer doesn’t seem so bad.

“I’m sorry,” I say. “I’m so sorry,” but she shoos me off and says no, that she’s the one who should be sorry. “I didn’t mean to make you sad,” she says, seeing my watery eyes. “Just wanted you to know that I can empathize. That I can relate. It’s never easy losing someone you love,” she says again, and then stands quickly from the armchair, gets back to tending to Mom. She tries to change the subject. “Feeling tired yet?” she asks again, and this time I tell her I don’t know. My body feels heavy. That’s as much as I knew. But heavy and tired are two different things.

She suggests then, “Why don’t I tell you a story while we wait? I tell stories to all my patients to help them sleep.”

Mom used to tell me stories. We’d lie together under the covers of my twin-size bed and she’d tell me about her childhood. Her upbringing. Her own mom and dad. But she told it like a fairy tale, like a once upon a time kind of story, and it wasn’t Mom’s story at all, but rather the story of a girl who grew up to marry a prince and become queen.

But then the prince left her. Except she always left that part out. I never knew if he did or if he didn’t, or if he was never there to begin with.

“I’m not your patient,” I remind the nurse but she says, “Close enough,” while dimming the overhead lights so that I can sleep. She sits down on the edge of my bed, pulling the blanket clear up to my neck with warm, competent hands so that for one second I envy Mom her care.

The nurse’s voice is low, her tone flat so she doesn’t wake Mom from her deathbed. Her story begins somewhere just outside of Moab, though it doesn’t go far.

Almost at once, my eyelids grow heavy; my body becomes numb. My mind fills with fog. I become weightless, sinking into the pitted hospital bed so that I become one with it, the bed and me. The nurse’s voice floats away, her words themselves defying gravity and levitating in the air, out of reach but somehow still there, filling my unconscious mind. I close my eyes.

It’s there, under the heavy weight of two thermal blankets and at the sound of the woman’s hypnotic voice, that I fall asleep. The last thing I remember is hearing about the snarling paths and the sandstone walls of someplace known as the Great Wall.

When I wake up in the morning, Mom is dead.

I slept right through it.

eden (#u298352a8-6366-5809-abab-2dbb2eb6f5bc)

May 16, 1996 Egg Harbor

Aaron showed me the house today. I’m in love with it already—a cornflower blue cottage perched on a forty-five-foot cliff that overlooks the bay. Pine floors and whitewashed walls. A screened-in porch. A long wooden staircase that leads down to the dock at the water’s edge where the Realtor promised majestic sunsets and fleets of sailboats floating by. Quaint, charming and serene. Those are the words the Realtor used. Aaron, as always, didn’t say much of anything, just stood on the balding lawn with his hands in the pockets of his jeans, staring out at the bay, thinking. He’s recently taken a job as a line cook at one of the restaurants in town, a chophouse in Ephraim. The cottage will more than cut his commute time in half. It’s also a steal compared to our current mortgage, and set on two acres of waterfront land that spans the heavily wooded backcountry to the rocky shores of Green Bay.

And there’s a garden. A ten-by-twenty-or thirty-foot space overrun with brambles and weeds. It’s in need of work, but already Aaron has promised raised beds. There is a greenhouse, a sorry sight if I’ve ever seen one, set in a sunnier patch of the yard where the grass still grows. Small, shedlike, with aged glass windows and some sort of clear, corrugated roof meant to attract the sun. The door hangs cockeyed, one of its hinges broken. Aaron took a look and said that he can fix it, which comes as no surprise to me. There isn’t a thing in this world that Aaron can’t fix. Cobwebs cling to the corners of the room like lace. Already I’m imagining rows and rows of peat pots of soil and seed soaking up the sun, waiting to be transported into the garden.

Nearby, a swing hangs from the mighty branch of a burr oak tree. It was the tree that cinched it for me. Or maybe not the tree itself, but the promise of the tree, the notion of children one day causing ruckus and mayhem on the tree’s swing, three feet of lumber fastened to the branch with a sturdy rope. I envision them climbing deep into the divots of the tree’s trunk and laughing. I can hear them already, Aaron’s and my unborn children. Laughing and screaming in delight.

Aaron asked if I loved it as much as him, and I didn’t know if he meant whether I loved the cottage as much as I love him, or if I loved the cottage as much as he loves the cottage, but either way I told him I did.

Aaron left the Realtor with our bid. It’s a buyer’s market, he said, trying to finagle the asking price down a good 10 percent. Me, I would have paid asking price, too afraid to lose the cottage otherwise. Tomorrow we’ll know if it’s ours.

Tonight I won’t sleep. How is it possible to love something so much, to want something so badly, when only hours ago I didn’t know it existed?

July 1, 1996Egg Harbor

The boxes are plentiful. There is no end to the number of cardboard boxes the movers carry through the front door, delivering them to their marked rooms—living room, bedroom, master bath—stomping across our home in dusty work boots. Sixteen hundred square feet of space needing to be filled as Aaron and I divvied up our gender-appropriate tasks, he directing the movers with couches and beds while I unpacked and washed the dishes by hand and placed them in the cabinets. I watched the many laps they took, each man’s head beginning to glimmer with sweat. Aaron’s too, though he hardly carried a thing, and yet the authority in his voice, the obvious clout as grown men trailed him through our home, heeding his every word, was enough to catch my eye. I watched him round the home time and again, wondering how I was so lucky to have him all to my own.

It wasn’t like me to be lucky in love. Not until I met Aaron. The men who came before him were deadbeats and drifters, bottom-feeders. But not Aaron. We dated for a year before he proposed. Tomorrow we celebrate two years. Soon there will be kids, a whole gaggle of little ones spinning circles at our feet. As soon as we’re settled, Aaron always said, and now, as my eyes assess the new home, the sprawling landscape, the sixteen hundred square feet of space, three bedrooms—two vacant and left to fill—I realize the time has come and like clockwork, something inside me starts to tick.

When the movers’ backs were turned, Aaron kissed me in the kitchen, pinning me against the cabinets, hands gripping my hips. It was unasked for and yet very much wanted as he kissed with his eyes closed, whispering that all of our dreams were finally coming true. Aaron isn’t one to be sentimental or romantic, and yet it was true: the cottage, his job, leaving the city. We’d both wanted to get away from Green Bay since the day we were married, his hometown and my hometown, so that two sets of parents couldn’t show up at our door on any given day, unsolicited, waging a secret battle as to which in-law could occupy the most of our time. We hadn’t gone far, sixty-seven miles to be precise, but enough that visits would be preempted with a simple phone call.

Tonight we made love on the living room floor to the glow of candlelight. The electricity had yet to be turned on and so, other than the dance of candlelight on the whitewashed walls, the house was dark.

Aaron was the first to suggest it, discontinuing my birth control pill, as if he knew what I was thinking, as if he could read my mind. It was as we lay together on the wide wooden floorboards staring out the open windows at the stars, Aaron’s prowling hand moving across my thigh, contemplating a second go. That’s when he said it. I told him yes! that I am ready for a family. That we are ready. Aaron is twenty-nine. I am twenty-eight. His paycheck isn’t extravagant, and yet it’s enough. We aren’t spendthrifts; we’ve been saving for years.

And even though I knew it wasn’t possible yet, the pill in my system nipped any possibility of pregnancy in the bud, I still imagined a creature no bigger than a speck starting to take form as Aaron again let himself inside me.

July 9, 1996Egg Harbor

Our days begin with coffee on the dock, bare feet dangling over the edge, downward toward the bay. The water is cold, and our feet don’t reach anyway. But as promised, there are sailboats. Aaron and I spend hours watching them pass by, as well as sandpipers and other shorebirds that come to call, their long legs wading through the shallow water for a meal. We stare at the birds and the sailboats, watching the sun rise higher into the sky, warming our skin, burning off the early-morning fog. Heaven on earth, Aaron says.

As we sit on the dock, Aaron tells me about his nights at the chophouse that steals him from me for ten hours at a time. About the heat of the kitchen, and the persistent noise. The rumble of voices calling out orders in sync. The sputter of boneless rib eye on the grill, the dicing and hashing of vegetables.

His voice is placid. He doesn’t complain because Aaron, ever easygoing Aaron, isn’t one to complain. Rather he tells me about it, describing it for me so that I can see in my mind’s eye what he’s doing when he’s away from me for half the day. He wears a white chef jacket and black chef pants and a cap, something along the lines of a beanie that is also white. Aaron’s been assigned the role of saucier, or sauce chef, one that’s new to him, but no doubt comes with ease. Because this is the way it is with Aaron. No matter what he tries his hand at, things always come with ease.

Our property is fringed by trees so that as we sit on the deck’s edge, Aaron and me, it feels as if we’re all alone, partitioned from society by the lake and the trees. If we have neighbors, we’ve never seen them. Never laid eyes on them. Never spied another home through the canopy of trees. Never are we disturbed by the sound of voices, but only the colloquy of birds as they perch in the trees and yammer back and forth about whatever it is birds talk about. On occasion the helmsmen will wave a hearty hello from behind the steering wheel of their sailboats, but more often than not they’re too far away to see Aaron and me at the dock’s edge, feet dangling southward, holding hands, sitting in silence, listening to the breeze through the trees.

We’re marooned on an island, stranded and shipwrecked, but we don’t mind. It’s just the way it should be.

Aaron’s work shift begins at two in the afternoon and ends when the last customer leaves and the kitchen is clean, most nights stumbling into bed around midnight or after, smelling of sweat and grease.

But the days are ours to do with as we please.

Last week, Aaron repaired the greenhouse door and we stripped it of cobwebs and bugs. We spent days cultivating the garden and Aaron made good on his promise of raised beds, three feet by five feet by ten inches deep, made of white cedar that will one day house cucumbers and zucchini. But not this year. It’s far too late in the season to grow produce this year and so for now, we buy it from any number of tatty roadside farm stands. We live two miles from town and even though the population around here expands sevenfold in the summer months thanks to a healthy tourist population, outside town it’s still mainly rural, long stretches of open country roads that intersect with nothing but sky.

Instead of planting produce this year, Aaron and I sowed perennial seeds to enjoy next year: baby’s breath and lavender and hollyhocks because all the fences and cottages around here, it seems, are flanked with hollyhocks. We placed them in peat pots of gardening soil in the greenhouse and set them in the sunniest spot we could find. In a month or so, we’ll transplant them to the garden. They won’t bloom for some time, not until next spring. But still, I stand hopeful in the greenhouse, staring at the peat pots, imagining what might be happening beneath the soil’s surface, whether the seeds’ roots are taking hold, pushing down into the soil to anchor the seedling to this world, or if the seed has merely shriveled up and died in there, a dead embryo in its mother’s womb.

As I clear out the last of my birth control pills and run a hand across what I imagine to be my uterus, I wonder what is happening inside there too.

jessie (#u298352a8-6366-5809-abab-2dbb2eb6f5bc)

I had Mom cremated at her request. I carry her around now in a rhubarb-glazed clay urn with a cork in the top, one she bought for herself when the cancer spread. It’s cylindrical and inconspicuous, the cork stuck on with an ample amount of Gorilla Glue so I don’t lose Mom by chance.

Mom had two wishes when she died, ones she let slip in the last brief moments of consciousness before she drifted off to sleep, a sleep from which she would never wake up. One, that she be cremated and lobbed from the back end of the Washington Island Ferry and into Death’s Door. And two, that I find myself and figure out who I am. The second hinged on the esoteric and didn’t make obvious sense. I blamed the drugs for it, that and the imminence of death.

I’m nowhere near accomplishing either, though I filled out a college application online. But I have no plans of parting with Mom’s remains anytime soon. She’s the only thing of value I have left.

I haven’t slept in four days, not since some doctor took pity on me and offered me a pill. Three if you count the one where I nearly nodded off at the laundromat waiting for clothes to dry, anesthetized by the sound of sweaters tumbling around a dryer. The effects are obnoxious. I’m tired. I’m grumpy. I can focus on nothing and my reaction time is slow. I’ve lost the ability to think.

Yesterday, a package arrived from UPS and the driver asked me to sign for it. He stood before me, shoving a pen and a slip of paper up under my nose and I could only stare, unable to put two and two together. He said it again. Can you sign for it? He forced the pen into my hand. He pointed at the signature line. For a third time, he asked me to sign.

And even then I scribbled with the cap still on the pen. The man had to snatch it from my hand and uncap it.

I’m pretty sure I’ve begun to see things too. Things that might not be real, that might not be there. A millipede dashing across the tabletop, an ant on the kitchen floor. Sudden movements, immediate and quick, but the minute I turn, they’re gone.

I keep track of the sleepless nights in the notched lines beneath my eyes, like the annual rings of a tree. One wrinkle for each night that I don’t sleep. I stare at myself in the mirror each day, counting them all. This morning there were four. The surface effects of insomnia are even worse than what’s going on on the inside. My eyes are red and swollen. My eyelids droop. Overnight, wrinkles appear by the masses, while I lie in bed counting sheep. I could go to the clinic and request something else to help me sleep. Some more of the clonazepam. But with the pills in my system, I slept right on through Mom’s death. I don’t want to think about what else I’d miss.

At McDonald’s, I’m asked if I want ketchup with my fries, but I can only stare at the worker dumbly because what I heard was It’s messed up when boats capsize, and I nod lamely because it is disastrous and sad, and yet so out of left field I can’t respond with words.

It’s only when he drops a stack of ketchup packets on my tray that my brain makes the translation, too late it seems because I hate ketchup. I dump them on the table when I go, the mother lode for someone who likes it. On the way out the door I trip, because coordination is also affected by a lack of sleep.

Two hours ago I dragged my heavy body from bed after another sleepless night, and now I stand in the center of Mom’s and my house, deciding which of our belongings to take and which to leave. I can’t stand to stay here much longer, a decision I’ve come to quickly over the last four days. I’ve spoken to a Realtor already, figured out next steps. First I’m to pack up what I want to keep, and then everything else will be sold in an estate sale before some junk removal service tosses the rest of our stuff in the trash.

Then some other family will move in to the only home I’ve ever known.

I’m eyeing the sofa, wondering if I should take it or leave it,when the phone rings. “Hello?” I ask.

A voice on the other end informs me that she’s calling from the financial aid office at the college. “There’s a problem with your application,” she says to me.

“What problem?” I ask the woman on the phone, afraid I’m about to be cited for tax evasion. It’s a likely possibility; I’d left blank every question on the FAFSA form that asked about adjusted gross income and tax returns. I might have lied on the application too. There was a question that asked if both of my parents were deceased. I said yes to that, though I don’t know if it’s true.

Is my father dead?

On the other end of the line, the woman asks me to verify my social security number for her and I do. “That’s what I have,” she says, and I ask, “Then what’s the problem? Has my application been denied?” My heart sinks. How can that be? It’s only a community college. It’s not like I registered for Yale or Harvard.

“I’m sure it’s just a weird mix-up with vital statistics,” she says.

“What mix-up?” I ask, feeling relieved for a mix-up as opposed to a denied application. A mix-up can be fixed.

“It’s the strangest thing,” she says. “There was a death certificate on file for a Jessica Sloane, from seventeen years ago. With your birth date and your social security number. By the looks of this, Ms. Sloane,” she says, and I amend Jessie, because Ms. Sloane is Mom. “By the looks of this, Jessie,” she says, and the words that follow punch me so hard in the gut they make it almost impossible to breathe. “By the looks of this, you’re already dead.”

And then she laughs as if somehow or other this is funny.

* * *

Today I’m looking for a new place to live. Staying in our old home is no longer a viable option because of the residual ghosts of Mom that remain in every corner of the home. The smell of her Crabtree & Evelyn hand cream that fills the bathroom. The feel of the velvet-lined compartments in the mahogany dresser. The chemo caps. The cartons of Ensure on the refrigerator shelf.

I perch in the back seat of a Kia Soul, trying hard not to think too much about the call from the financial aid office. This is easier said than done. Just thinking about it makes my stomach hurt. A mix-up, the woman claimed, but still, it’s hard to grapple with the words you and dead in the same sentence. Though I try to, I can’t push them from my mind. The way she and I left things, I’m to provide a copy of my social security card to the college before they’ll take another look at my application for a loan, which is a problem because I don’t have the first clue where the card is. But it’s more than that too. Because the woman also told me about some death index my name was found on. A death index. My name on a database maintained by the Social Security Administration of millions of people who have died, nullifying their social security numbers so that no one else can use them, so that I can’t use my own social security number. Because, according to the Social Security Administration, I’m dead.

You might want to look into that,she’d suggested before ending our call, and I couldn’t help but feel shaken up by it even now, hours later. My name on a death database. Though it’s a mistake, of course.

But still I pray this isn’t some sort of foresight. A prophecy of what’s to come.

I gaze out the window as some woman sits behind the wheel of the Kia, steering us through the streets of Chicago. Her name is Lily and she calls herself an apartment finder. The first I’d heard of Lily was days ago, when I’d come home from a cleaning job—hating the feeling of coming home to Mom’s and my empty house alone, wishing she was there but knowing she would never be again, making a flip decision to sell the home and leave. I came home, leaving my bike on the sidewalk, and there, hanging on the handle of our front door, was an ad for Lily’s efficient and cost-free services. An apartment finder. I’d never heard of such a thing, and yet she was just the thing I needed. The door hanger was in-your-face marketing, the kind I couldn’t recycle with the rest of the junk mail. And so I called Lily and we made an appointment to meet.

Lily’s parallel parking skills are second to none, though it seems easy enough for someone like me who’s never driven a car before. Growing up in an old brick bungalow in Albany Park, there was never a need to drive a car. We didn’t have one. The Brown Line or the bus took us everywhere we needed to go. Either that or our own two feet. I also have my Schwinn, Old Faithful, which is surprisingly resilient in even the worst weather, except for, of course, three feet of snow.

I was fifteen when Mom was diagnosed with cancer, which meant that for the time being, my life was on hold, anything that wasn’t essential set aside. I went to school. I worked. I helped with the mortgage and saved as much as I could. And I held Mom’s hair for her when she puked.

She found the lump herself, slim fingers palpating her own breast because she knew sooner or later this would happen. She didn’t tell me about the lump until after she’d been diagnosed with cancer, one mammogram and a biopsy later. She didn’t want to worry me. They removed the breast first, followed by months of chemotherapy. But it wasn’t long before the cancer returned, in the chest and in the bones this time. The lungs. Back for vengeance.

Jessie, I’m dying. I’m going to die, she had said to me then. We were sitting on the front porch, hand in hand, the day she learned the cancer was back. At that point, her five-year survival rate took a nosedive. She only lived for two more, and none of them great.

The cancer, it’s hereditary. Some aberrant gene that runs through our family line, red pegs lined up in my battleship already. Like Mom and her mom before her, it’s only a matter of time before I too will sink.

I claimed the back seat of the Kia after Lily dropped her purse into the passenger’s chair. She drives with one hand on the horn at all times, so she can scare pedestrians out of the way, those she hollers at from behind safety glass to shake a leg and scoot your boot. I have no credit history and no bank account, which I’ve confessed to Lily, and instead carry a pocketful of cash. Her eyes grew wide when I showed her my money, thirty hundred-dollar bills folded in half and stuck inside a wristlet.

“This might be a problem,” Lily said, shrugging her shoulders not at the cash but rather the shortage of credit, the absence of a bank account, “but we’ll see.”

She suggested I offer a landlord more up front to offset the fact that I’m one of those people who keeps all my money in a fireproof safe box beneath my bed. The checks I earn cleaning houses get cashed at Walmart for a three-dollar service fee, and then deposited into my trusty box. I considered signing on with a temp agency once, but thought better of it. There are perks to my job I won’t find anywhere else. Because I’m cleaning houses, I don’t have to pay taxes to Uncle Sam. I’m an independent contractor. At least that’s the way I’ve always rationalized it in my head, though, for all I know, IRS agents are hot on my heels, planning to nab me for tax evasion.

And still, I load my cleaning supplies into a basket on the back end of Old Faithfuleach day and pedal off to work, earning as much as two hundred dollars some days by cleaning someone else’s home. I do it in peace with my headphones on. I don’t have to make small talk. No one supervises me. It’s the best job in the world.

“Either that,” said Lily as she easily navigated the streets of Chicago, pulling in to an alley behind a high-rise on Sheridan and putting the car in Park, “or you’ll need to find someone to cosign on the loan,” which isn’t an option for me. I have no one to cosign on the loan.

The apartment search is nearly an abject failure.

Lily shows me apartment after apartment. A third-floor unit in a high-rise in Edgewater. A mid-rise on Ashland, newly rehabbed, in my price range though at the high end of it. Unit after unit of boxlike rooms enclosed by four thin gypsum walls, foggy windows that inhibit the light from coming in. The window screens are torn, one stuffed full with an air-conditioning unit, which is supposed to make me happy because, as Lily points out, renters usually have to buy them themselves, those repulsive window units that bar any natural light from entering the room.

The kitchens are tight. The stoves are old and electric. Freckles of mold grow in the showers’ grout. The closets smell like urine. Lightbulbs have burned out.

But it isn’t the mold or the windows that bother me. It’s the noise and the neighbors—strange people just on the other side of drywall, their domestic life partitioned from mine by a paltry combination of plaster and paper. The sense of claustrophobia that settles under my skin as I pretend to listen to Lily as she goes on and on about the two hundred and eighty square feet in the unit. The laundry facilities. The high-speed internet. But all I hear is the noise of someone’s hair dryer. Women laughing. Men upstairs screaming at a ball game on TV. A phone conversation streaming through the walls. The ding of a microwave, the smell of someone’s lunch.

Four days without sleep. My body is tired, my mind like soup. I lean against the wall, feeling the force of gravity as it threatens to tug my heavy body to the ground.

“What do you think?” Lily asks over the noise of the hair dryer, and I can’t help myself.

“I hate it,” I say, for the eighth or ninth time in a row, one for as many apartments as we’ve seen. Insomnia does that too. It keeps us honest because we don’t have the energy to manufacture a lie.

“How come?” she asks, and I tell her about the hair dryer next door. How it’s loud.

Lily keeps composed, though inside her patience with me must be wearing thin. “Then we keep looking,” she says as I follow her out the door. I’d love to believe that she wants me to be happy, that she wants me to find the perfect place to live. But ultimately it comes down to one thing: my signature on a dotted line. What a lease agreement means for Lily is that an afternoon with me isn’t a complete waste of time.

“I have one more to show you,” she says, promising something different from the last umpteen apartments we’ve seen. We return to the Kia and I buckle up in the back seat, behind the purse that’s already riding shotgun. We drive. Minutes later the car pulls to a sluggish stop before a greystone on Cornelia, gliding easily into a parking spot. The street is residential, lacking completely in communal living structures. No apartments. No condominiums. No high-rises with elevators that overlook crappy convenient marts. No strangers milling around on street corners.

The house is easily a hundred years old, beautiful and yet overwhelming for its grandeur. It’s three stories tall and steep, with wide steps that lead to a front porch. A bank of windows lines each floor. There’s a flat-as-a-pancake roof. Beneath the first floor there’s a garden apartment, peeking up from beneath concrete.

“This is a three flat?” I ask as we step from the car, envisioning stacks of independent units filling the home, all united by a common front door. I expect Lily to say yes.

But instead she laughs at me, saying, “No, this is a private residential home. It’s not for sale, not that you could afford it if it was. Easily a million and a half,” she says. “Dollars, that is,” and I pause beneath a tree to ask what we’re doing here. The day is warm, one of those September days that holds autumn at bay. What we want is to climb into sweaters and jeans, sip cocoa, wrap ourselves in blankets and watch the falling leaves. But instead we drip with sweat. The nights grow cold, but the days are hot, thirty-degree variants from morning to night. It won’t last long. According to the weatherman, a change is coming, and it’s coming soon. But for now, I stand in shorts and a T-shirt, a sweatshirt wrapped around my waist. When the sun goes down, the temperature will too.

“This way,” Lily says with a slight nod of the head. I hurry along after her, but before we round the side of the greystone, something catches my eye. A woman walking down the sidewalk in our direction. She’s a good thirty feet away, but moving closer to us. I don’t see her face at first because of the force of the wind pushing her dark hair forward and into her eyes. But it doesn’t matter. It’s the posture that does it for me. That and the tiny feet as they shuffle along. It’s the unassuming way she holds herself upright, curved at the shoulders just so. It’s her shape, the height and width of it. The shade and texture of a periwinkle coat, a parka, midthigh length with a drawstring waist and a hood, though it’s much too warm for a coat with a hood.

The coat is the same one as Mom had.

I feel my heart start to beat. My mouth opens and a single word forms there on my lips. Mom. Because that’s exactly who it is. It’s her; it’s Mom. She’s here, alive, in the flesh, coming to see me. My arm lifts involuntarily and I start to wave, but with the hair in her eyes, she can’t see me standing there on the sidewalk six feet away, waving.

Mom doesn’t look at me as she passes by. She doesn’t see me. She thinks I’m someone else. I call to her, my voice catching as the word comes out, so that it doesn’t come out. Instead it gets trapped somewhere in my throat. Tears pool in my eyes and I think that I’m going to lose her, that she’s going to keep walking by. And so my hand reaches out and latches on to her arm. A knee-jerk reaction. To stop her from walking past. To prevent her from leaving.

My hand grabs a hold of her forearm, clamping down. But just as it does, the woman frees her face of the hair and casts a glance at me. And I see then what I failed to see before, that this woman is barely thirty years old, much too young to be my mother. And that her face is covered in an enormity of makeup, unlike Mom, who wore her face bare.

Her coat is not periwinkle at all but darker, more like eggplant or wine. And it has no hood. As she nears, I see more clearly. It isn’t a coat after all, but a dress.

She looks nothing like Mom.

For a second I feel like I can’t breathe, the wind knocked out of me. The woman tugs her arm free. She gives me a dirty look, scooting past me as I slip from the sidewalk, my feet falling on grass.

“I’m sorry,” I whisper as she skirts eye contact, avoids my stare. She moves to the far edge of the sidewalk where she’ll be two feet away, where I can’t reach her. “I thought you were someone else,” I breathe as my eyes turn to find Lily with her arms folded, trying to pretend that this didn’t just happen.

Of course it’s not Mom, I tell myself as I watch the woman in the eggplant dress move on—faster now, no longer shuffling along but now walking at a clipped pace to get away from me.

Of course it’s not Mom, because Mom is dead.

“You coming?” Lily asks, and I say yes.

I follow Lily as we sneak along a brick paver patio and into the backyard. My heart still beats hard. My nerves are rattled. The backyard opens up to reveal a patio and a yard, and behind that, a red brick garage with a jade green door. “This is why we’re here,” says Lily, gesturing to the garage, and I stop where I am and ask, “You want me to live in a garage?”

“It’s a carriage house,” she says, explaining how there’s living space up above, as is apparently evidenced by a window or two on the second and third floors. “These are quite the find. Some people love them. The minute they come on the market, they’re usually gone. This listing just came in this morning,” she says, telling me how carriage houses used to be just that in the olden days, a place to park a horse and buggy and for the carriage driver to live. Servants’ quarters. They’re tucked away on an alley, camouflaged behind a far less humble house, living in the shadows of something bigger and better than them.

Which seems to me to be just the thing I need. To be camouflaged, to live hermit-like in seclusion, in the shadows of something grand.

“Can we see?” I ask, meaning the inside, and Lily lets us in through a tall, tapered front door and immediately up a flight of rickety stairs.

It’s larger than anything we’ve yet seen, nearly five hundred square feet of living space that is dilapidated and old, everything painted a hideous brown. The wooden floors have taken a beating. The boards are squeaky and uneven, with square-cut nails that lift right up out of the floorboards to a toe-stubbing height. The kitchen lines a living room wall, if it can even be called a kitchen. An old stove, an old refrigerator and a small bank of cabinets lined in a row beside where a TV should go. The lighting fixtures are archaic, giving off a scant amount of light. The place is minimally furnished; just a couple pieces of furniture that look to be about as decrepit as the home.

The bathroom appears to have had minor renovations. The fixtures, the paint are new, but the floor tile looks to be older than me. “You won’t hear a neighbor’s hair dryer from here,” Lily says. The so-called bedroom is up a second flight of precarious stairs, a loftlike space with an arched ceiling that follows the low roofline.

On the top floor I can’t stand upright. I have to hunch.

“This is hardly suitable living space,” says Lily, bent at the neck so she doesn’t hit her head. Her wedge sandals struggle down the wooden steps, her hand clinging to the banister lest she fall. She doesn’t think I will like it, but I do.

Carriage homes like these, Lily says, don’t follow the same rules as prescribed in the city’s landlord-tenant ordinance. I wouldn’t be protected in the same way. They’re overlooked when it comes to regular safety inspections. There’s only one door, which generally goes against fire codes that require two. Because garbage bins are relegated to the alley that abuts this home, it can be loud. The smell, especially in the summer months, can be sickening, she says.

“Rats are bent on eating from garbage bins, which means...” she begins, but I hold up a hand and stop her there. She doesn’t need to tell me. I know exactly what she means.

“What do you think?” Lily asks.

I listen for the sound of women’s laughter. For rowdy men screaming at a TV. There are none.

“How do I apply?” I ask.

Lily takes care of the paperwork. The landlord is a woman by the name of Ms. Geissler, a widow who lives alone in the greystone. We never meet, though Lily provides her with my completed application, a list of references—ladies whose homes I clean—and a letter of recommendation from a former high school guidance counselor. I kiss three grand goodbye, enough to cover first and last months’ rent, plus two more for good measure. As they say, money speaks.

At Lily’s suggestion, I wait in the car while she goes inside to meet with the landlord. I hold my breath, knowing it’s liable the landlord will soon discover the same slipup as the college’s financial aid office. That my social security number belongs to a dead girl. And she’ll deny my application.

But, to my great relief, she doesn’t. It takes less than fifteen minutes for Lily to emerge through the front door of the greystone, a key ring in hand. The keys to the carriage home. I breathe a sigh of relief. As it turns out, Lily let on about my mom and for that reason, Ms. Geissler approved the application without vetting me first. Out of sympathy and pity. Because she felt sorry for me, which is fine by me, so long as I have a place to live. A place that doesn’t remind me of Mom.

As we pull away, I stare out the window and toward the imposing home. It’s masked in shadows now, the sun slipping down on the opposite side of the street, burying the greystone in shade. The house is dignified but solemn. Sad. The house itself is sad.

From the third story, I watch the window shade slowly peel back, though what’s on the other side I can’t see because it’s shadowy and dim. But I imagine a woman, a widow, standing on the other side, watching until our car disappears from view.

eden (#u298352a8-6366-5809-abab-2dbb2eb6f5bc)

July 26, 1996 Egg Harbor

It just so happens that we do have neighbors.

They came this afternoon after Aaron had gone off to work, a pregnant Miranda and her two boys, five-year-old Jack and two-year-old Paul. They came trudging down our gravel drive, Miranda pulling both boys in a red Radio Flyer wagon so that by the time they arrived she was sweaty and spent. She’d come to deliver a welcoming gift.

It was the sound of wheels on gravel that caught my attention as I stood on a ladder, painting the living room walls a pale gray, the windows and doors open to expel chemical scents from the air. This is how I now spend my days when Aaron is away. Unpacking boxes of belongings. Cleaning the insides of closets and cabinets. Painting the home.

I saw them through the window first, heard the tired woman growl at the boys to stop crying and to behave, her cheeks flushed red from the heat and the pregnancy and, I guessed, the desire to impress. Her blond hair blew around her face and into her eyes as she walked. Her body was cemented with a short maternity dress, fastened to her with sweat. On her feet were Birkenstocks. In her eyes, exhaustion and discontent. From the moment I first spied her out the open window I knew one thing: motherhood did not suit her well.

I set down my painting supplies and met them on the porch. Dropping the wagon’s handle, Miranda introduced herself first and then the kids, neither of whom said hello, for they were far too busy clawing their way out of the wagon, elbowing one another for room on the porch step. I didn’t mind. They had blond hair like their mother, and if it weren’t for the apparent age difference could have easily been twins. They fought one another, vying for the right to their mother’s free hand. The bigger of the two won out in the end and as he slipped his hand inside Miranda’s, the little guy fell to the ground in a puddle of tears. “Get up,”Miranda commanded, her sharp voice jabbing through the placid air, apologizing to me for their manners as she tried hard to raise Paul from the ground. But Paul was a deadweight and wouldn’t stand, and as she tugged on his underarms he cried out in pain that she’d hurt him. Tears came pouring from his eyes.

“Damn it, Paul,” she said, pulling again roughly on those underarms. “Get up.”

What she saw were naughty children making a fuss, embarrassing her, making her feel humiliated and ashamed. But not me. I saw something else entirely. I dropped down beside little Paul and held out a hand to him. “There’s a tree swing in the backyard. Let’s go have a ride on it, and let Mommy rest awhile?”I said. His pale green eyes rose to mine, snot gathering along his nostrils, running downward toward his lips. He wiped at his nose with the back of a dirty hand and nodded his sweet little head.

Miranda had walked far to bring us a blueberry loaf, more than a block in the heat. The pits of her dress were damp with sweat, the cotton pulled taut across the baby bump. When she spoke, her voice was breathless, exhausted, burned-out from the energy it took to raise two boys on her own, and she confessed to me that this time—while running a hand over that baby—she was hoping for a girl.

She sat on a patio chair, kicking off her Birkenstocks and resting her swollen ankles on another seat as I poured us each a glass of lemonade, conscious of the dried paint on the backs of my hands.

Miranda’s husband, she told me, is employed by the Department of Public Works. She stays at home with Jack and Paul, though what she always wanted to be—what she used to be in her life before kids—was a medical malpractice attorney. She asked how long Aaron and I have been married and when I told her, her eyebrows rose up in curiosity and she asked about kids.

Do we have them?

Do we plan to have them?

It seemed an intimate conversation to have with someone I hardly knew, and yet there was a great thrill at saying the words aloud, as if cementing them to reality. I felt my cheeks redden as I thought of that morning before dawn when Aaron rose, dreamlike, above me, lifting my nightgown up over my head. Outside it was dark, just after four o’clock in the morning, and our eyes were still drowsy, heavy with sleep, our minds not yet preoccupied by the thoughts that arrive with daylight. We moved together there on the bed, sinking into the aging mattress. And then later, while grinning at each other over mugs of coffee on the dock, watching as the fleets of sailboats went floating by on the bay, I had to wonder if it happened at all, or if it was only a dream.

When Miranda asked, I told her that we’re trying. Trying to have a child, trying to start a family. An odd choice of words for creating a baby, if you ask me. Trying is how one learns to ride a bike. To knit, to sew. To write poetry.

And yet it was exactly what we were doing as Aaron and I made love with reckless abandon, and then followed it up a week or two later with a home pregnancy test. The tests were all negative thus far, that lone pink line on the display screen notifying me again and again that I wasn’t yet pregnant. I tried not to let it get the best of me, and yet it was hard to do. It wasn’t as though Aaron and I minded the time spent trying; in fact, we enjoyed it quite a bit, but with every passing month I yearned exponentially more for a baby. For a baby to have, a baby to hold.

I never mentioned to Aaron that I was taking the pregnancy tests.

I took them while he was at work, watching out the cottage window as his car slipped from view and then, when he was out of sight, rushing to the bathroom, where I closed and locked the door in case he mistakenly left something behind and had to return for it.

And then, when the single pink line appeared on the display screen as it always did, I wrapped the negative pregnancy test sticks up in tissue and discarded them discreetly in the garbage bins.

Miranda beamed when I told her that we’re trying. “How exciting!”she told me, her smile mirroring the one on my own face.

And then, helping herself to a slice of her own blueberry loaf and running a hand over her bump for a second time, she said that her baby and my baby could one day go to school together.

That they could one day be friends.

And it was a thought that filled me with consummate joy. I grinned.

I’d been a lone wolf for much of my life. An introvert. The kind of woman who never felt comfortable in her own skin. Aaron changed that for me.

The idea thrilled me to bits and, in turn, I instinctively stroked my own empty womb and thought how much I wanted my baby to have a friend.

jessie (#u298352a8-6366-5809-abab-2dbb2eb6f5bc)

Tonight makes five days since I’ve been asleep. It’s my first night in my new place. I spend it not sleeping, but rather imagining myself dead. I think of what it must be like for Mom, being dead. Is there blackness all around her, a pit of nothingness, the blackest of the black holes? Or has time simply stopped for her, and there’s no such thing anymore as the living and the dead? Sometimes I wonder if she’s not dead at all but rather alive in the clay urn of hers, screaming to get out. I wonder if there’s enough oxygen in the urn. Can Mom breathe? But then I remember it doesn’t matter anyway.

Mom is dead.

I wonder if it hurts when you die. If it hurt when Mom died. And I think, in frightening detail, what it feels like when you can’t breathe. I find myself holding my breath until my lungs begin to hurt, to burn. It’s a prickling pain that stretches from my throat to my torso. It’s reflexive, automatic when my mouth gapes open, and I suck in all the oxygen I can to soothe the burn.

It hurts, I decide. It hurts to die.

There’s a clock on the wall, one that came with the house. Tick, tock, tick, tock, it goes all night long, keeping track of the minutes I don’t sleep. Keeping count for me. It’s loud, a conga drum pounding in my ear, and though I try and remove the batteries, the tick, tock doesn’t go away. It stays.

I feel out of place in this strange place. The house smells different than what I’m used to, an earthy smell like pine. It’s older than Mom’s and my old home, where I lived my entire life. One of the windows doesn’t close tight so that when the wind whips its way around the house as it does tonight, air sneaks in. I can’t feel it but I hear it, the hiss of the wind forcing its way in through a gap.

I lie there in bed, trying hard to catch my breath, to not think about dying, to will myself to do the impossible and sleep. Beside me, on the floor, are four boxes, the only ones I brought from the old home. Some clothes, a few picture frames, and a box of random paperwork Mom kept, just an old white bankers box, kept closed with a string and button. It seemed important enough for Mom to keep, and so I kept it. A thought comes to me now: Could my social security card be in that box, tucked away with Mom’s financial paperwork?

I climb out of bed and turn on a light, dropping to the floor beside the box. I loosen the string and lift the lid, meeting reams of paper head-on. If there’s any sort of method to the madness, I don’t see it.

I search through the paperwork for my social security card, to be sure the numbers I dashed off on the FAFSA form weren’t incorrect. That I didn’t write the wrong ones down by mistake. Because never in my life have I been asked to give my social security number, and so it’s conceivable, I think, that I have the numbers mixed-up. I look for the card itself, grabbing stacks of paper by the handful and flipping through them one sheet at a time, hoping the card falls out. But instead I find the deed to our home, an old checkbook ledger. Gas and electric bills. Years’ worth of tax returns that gives me pause, because if I know one thing, it’s that Uncle Sam isn’t about to pay out tax refunds without a social security number.

I set everything else aside except for the tax returns. My eyes go straight to the exemptions, the spot where someone would list their dependents and their dependents’ social security numbers, meaning me and my social security number. Except that when I come to it, I find the line blank. Mom didn’t list me as a dependent and, though I double-check the year of the form to be sure I was alive at the time, I see that I was. That I was eleven years old at the time the form was completed.

And though I don’t know much about income taxes, I do know it would have saved Mom a buck or two if she had thought to use me as a tax deduction. A baby gift from Uncle Sam.

I wonder why Mom, who was frugal to a fault, didn’t claim me as a dependent that year.

It was a mistake, I think. An oversight only. I dig through to find another 1040 in the tower of paperwork—this one older, when I was four years old—and search there for my name and social security number, finding it nowhere. Another year that Mom didn’t claim me.

I sift through them all, six tax return forms that I can find—my movements becoming faster, more frantic as I dig—and discover that never once did Mom claim me as a dependent. Not one single time.