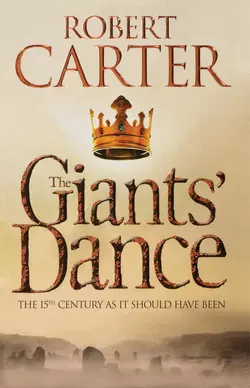

The Giants’ Dance

Robert Carter

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Фэнтези про драконов

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 619.36 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A rich and evocative tale set in a mythic 15th century Britain, to rival the work of Bernard Cornwell.