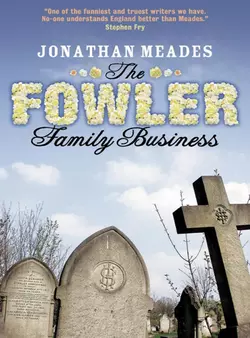

The Fowler Family Business

Jonathan Meades

‘One of the funniest and truest writers we have. No one understands England better than Meades.’ Stephen FryAn inventively nasty, gruesomely comic paean to the sylvan heights of Forest Hill and Upper Norwood, a warped map of the death trade’s quotidian strangeness.Henry Fowler was twice, long ago, runner-up in the Oil Fuels Guild-sponsored Young Funeral Director of the Year competition. His intense loyalties are to his parents, to his wife and children, to the family firm and the trade it practises, to his native south-east London and to his best friend Curly, traffic wonk and surviving brother of his former best friend who fell to his death at Norwood Junction. Well into middle age, and Henry’s life is running smoothly as he always hoped it would. But then: his wife’s tennis partner, a celebrity florist and BBC2 star is accidentally beheaded by his electric hedgecutter while crimping a three metre high topiary poodle; Curly, newly married and eager for a child is diagnosed as suffering ‘waterworks problems’; and Henry, suddenly doubtful of his wife’s fidelity, cuts a lock of his sleeping daughter’s hair. The foundations of a world, a family and an identity begin to rock.

The Fowler Family Business

Jonathan Meades

Dedication (#ulink_6afaa2b6-8214-5bab-b528-9803be6fd9c7)

For: H, R, L, C – and C

Contents

Cover (#u0f81d0bb-1ea1-56fe-bf1c-8b3fb9bcd272)

Title Page (#u0f109bd5-24a3-50be-a6df-2b66d6ebd96c)

Dedication (#u72a90b6e-aa3f-5293-a64e-dc126639c822)

Chapter One (#uaf9ace85-9f40-5768-ac2d-19d5b57cb607)

Chapter Two (#uff04b40b-e191-55f0-b620-ad8ace5c2cdd)

Chapter Three (#uf2bbcc8b-3727-5158-85da-20ebbceb8c9e)

Chapter Four (#uadfee7aa-1cc1-5c7c-b06f-7026b8e9baaa)

Chapter Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Other Works (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#ulink_54326e64-e2dd-5fd1-8e98-ef7457155a2c)

Once it had been Henry and Stanley, Stanley and Henry. Stanley was the card, not Henry. Stanley was a caution, Henry wasn’t, Henry was cautious. Stanley was his da’s boy – all chat, and then some, such a tongue in his mouth. Henry’s tongue was fixed in the prison of his teeth whose incisor accretions, plaque, molar holes and food coves were his friendly familiars. You chum up with those ravines and contours if you’re tongue-tied. You go in for interior potholing. You have friends inside, three dozen of them, each with its tidemark of salts from forgotten meals, from grazes taken with Stanley, from wads shared on the way to school, from midnight feasts when they stayed over at each other’s.

It was always Henry and Stanley. Stanley was such a one. It was always the two of them together, Stanley taking the lead, Henry gingering along behind whilst Stanley got into scrapes and scrumped and larked about and scaled the old Victoria plum tree which Mr Fowler called ‘Her Majesty’. Mr Fowler watched in trepidation as Henry clambered about the lower boughs (Stanley was already at the top, his head poking through the leaves). He feared that his precious son might tumble and crack his crown and so be taken from him and Mrs Fowler – though, heaven knows, it was Stanley’s da who had more cause to harbour such a fear for he and Mrs Croney had lost an infant girl to diphtheria the winter before the war ended. Stanley was the hasty replacement, born less than a year after Wendy, poor mite, had perished.

Mr and Mrs Fowler were paranoiacally protective of Henry who reciprocated with a dutiful obedience which masked his timidity: he never ventured out of his depth, he never ran across the road, he was a responsible cyclist. Henry was irreplaceable.

In their family they were, all three of them, fans of Charlie Drake, the squeaky knockabout comic. Knockabout! He surely put himself through it. His weekly television show was a self-inflicted assault course. They howled with laughter in the curtained room lit by cathode blue. Mr Fowler with his Saturday bottle of Bass, Mrs Fowler with her fifty-two-weeks-a-year Christmas knitting, Henry in his raglan and pressed flannels, the three of them wondering what the irrepressible little trouper would get up to next. He tumbled, our Charlie fell. He crashed through walls. He went A over T into porridge vats. He’d better watch out for himself – Mr Fowler said as much. ‘Ooh he’s going to come a cropper Mother!’

Then he added, he always added, he put down his tankard and added gravely: ‘Don’t ever – don’t you ever – you listening Henry my boy – don’t you ever think of trying that. Don’t you ever.’

Pearl one, stitch one, take one in. ‘And don’t,’ Mrs Fowler joined in, ‘ever do what Stanley was doing up Her Majesty either. I don’t know …’

Henry Fowler didn’t require such warnings. He was a watcher. He anticipated the worst. He observed Stanley’s clinging limbs as he did Charlie Drake’s flying ones. He observed them with contained blood-lust – the ability to put the limbs together again, nicely, for the relatives, was, after all, the family trade. When Charlie Drake crashed about Henry rocked to and fro on the settee, with his tongue in his teeth, rooting out the rotten holes, laughing with his mouth shut. He got eager, he got agitated. He willed injury on Charlie who lived nearby in Lawrie Park Road – he dreamed of being the one who would make Charlie, our Charlie, look more like Charlie, in death, than he had ever looked in life, so like Charlie that his kith’n’kin would hardly notice he’d passed over. He wanted Charlie to hurt himself that badly so that he might practise the trade passed down to him by his father and his father’s father who had founded the business in 1901 when he was just a young undertaker and Her Majesty the Queen and Empress Victoria had only lately died. He dreamed too that Stanley might one day be thrown from weak, ungrippable branches by a high gust and so leave the tree for the ground. The sky would be dazzling lactic grey.

Stanley was his friend, he was such a friend he was a brother – he implored his parents to give him a real brother but they disobliged. Stanley was so much a brother he loved him, he loved him so much that he wanted to break him, the way that adored toys are dismembered. They put toy boxes beneath the carpet in Henry’s bedroom to simulate B- Western canyons. The Sioux would ambush the cowboys. The transgressors, defeated, would be beheaded by Henry’s fretsaw. When the change from lead to plastic models was made, towards the end of their Indian wars, a penknife sufficed. After he had cut the head off Henry always wanted to reattach it, he always regretted what he had done.

Head wounds were Mr Fowler’s speciality. He had the good fortune to work in the golden age of head wounds. Health and Safety legislation was something he gloried in as an employer. He was a grateful beneficiary of its loopholes and of the laxity of its implementation. He had followed a war, in the company of an army padre, burying the still helmeted at Arromanches, in a wood near Rouen where ‘the chalk was like concrete’, and all around Caen (‘Canadian lads – hardly got their bum-fluff some of ’em’). In that war he had risen to sergeant-major, and after it he had dropped the sergeant part. And after it, too, he had revelled in the automotive potency of the age. Cars might not have been as routinely quick as they are today but they still got up a fair lick on roads that were built for old legions, horses, first-generation internal combustion. He had served in a war for his King and he believed from the very bottom of his still undicky ticker that mortal risk was the prerogative of everyone – save Henry, who was precious and irreplaceable.

Mr Fowler was happiest with A-roads, with arterial roads with central flower displays. He loved road-houses which men drove to with their bit on the side to get tight in, to adulterate marriage in a private room secured with a wink and a tip, to drink more after, to exit into the path of an oncoming vehicle. The metalled pelt of roads outside road-houses was frosted in winter, soft in summer (the season of minor mirages). The whole year through it was constellated with the evidence: red glass, rubber, chromium, cloth, Naugahyde, oil, body tissue, blood, especially blood. Every road-house had a bloody road in front of it. There were deaths galore. Racing drivers set an example to the male nation. They led short fast lives: Collins, Hawthorn, Lewis-Evans, Scott-Brown with his two names and one arm. They expected nothing more. In their mortal insouciance and dashing dress they aped The Few. They drove to die in flames and glory. After them young death would be delivered by the pharmacopoeia: no head wounds there.

And there were no seat-belts then, no collapsible steering columns, no impact-triggered air bolsters fighting for space like naked fatties. There was no obligation on motorcyclists to wear helmets. The first British motorways – the very name acknowledges the unsuitability of previous roads – were being dug and levelled when Mr Fowler was in his prime. In his old age he was sad but philosophical about the diminution in road deaths effected by motorways and about the decline of ‘random culling’, an epithet which, as a child, Henry believed to be in general use rather than specific to his father. ‘It’s Nature’s way. Nature always finds a way. War, disease, pogroms, the South Circular, a faulty earth. You make the place too safe and, well – it’s not just the trade that’s going to feel it. The world’ll be full of old ’uns. Miserable old parties like yours truly … Life was meant to be a banana skin. Look at the Bible, my lad.’

The week the Ml opened Mr Croney took Stanley and Henry for a drive up it. He couldn’t get the hang of the lanes, but neither could the rest of the grockles – this road was not a utility but a site to see, a novelty attraction to participate in. Every car was filled with children agape at the infantile simplicity of the enterprise, children who recognised that their solemnly playful way of making a road had been borrowed by grown-ups. Here was a model road whose scale had been multiplied by giants. It was so obvious, it was so uncompromising in its totalitarian certainty. It had started from zero. It was the road to the future which was already here, in Herts and Bucks. In the future there were picnickers on a December hard shoulder. They were scudding along part of the apparatus that would take them to the moon. Stanley, who dreamed of becoming a pilot, would by 1980 be an old moon hand, a veteran of weekly trips. Henry, who never considered any trade other than the family’s, would by 1980 be burying people on the moon, if, by 1980, people didn’t live for ever. Tomorrow: monorails. The day after tomorrow: the defeat of gravity. All mankind will be happy and there will be no lapels. Our shoes will shine for ever. The Queen’s means of transport will allow her to visit every one of her subjects each year for a cup of rehydre and a chat.

Mr Croney couldn’t wait to leave the future behind and get back to the roads of the present. He slowed in the outside lane indicating right (he was not the only one to do so). It was obvious to the boys, who had never driven, how to exit from the most exciting road they had seen. By the time he had veered across to the nearside lane complaining of a life sentence on this bloody road he was sweating and tetchy. At last he succeeded in getting off it. They crossed a bridge where children stood waving Union flags at the adventurers below. Mr Croney unscrewed the top of his pigskin-covered flask and swigged, relieved, steering with one hand, muttering: ‘Now this is what I call a road. The MI’ll never catch on you know.’

Stanley and Henry knew that overhanging bushes and muddy verges and drunken curves would be eliminated by their generation. Mr Croney drove down labyrinthine lanes and parked on the gravel outside a pub with a red sign and plenty of two-tone cars (baby blue and cream, carmine and tan). ‘Church,’ announced Mr Croney and went inside. The boys knew the form. He soon reappeared with crisps and ginger beer for them to share in the car. ‘I want real beer, Dad – this is for kids.’

Henry was shocked by Stanley’s brashness. He’d never dare make such a demand of his father. He was puzzled too by Mr Croney’s resigned acquiescence: he returned a few minutes later with two bottles of beer and a couple of pork pies. Stanley, enthused by the motorway and comparing it to American highways, hardly thanked his father but took the bottles and said to Henry: ‘I’ll have yours. You don’t want it do you?’ Stanley put his new grey winkle-pickers on the dashboard and lounged with proprietorial abandon listing the attractions of America which is where he would live when he was a pilot: ‘They all go on the first date … fantastic money even before you’ve finished training … square watches … record-players in cars … open-plan houses …’ Henry sat on the back seat masticating the pie’s pink meat. Stanley lobbed his from the window: ‘Electric windows … amazing jeans. It’s the country of the foreseeable future,’ he said, repeating a magazine headline.

Henry’s foreseeable future was already mapped out within a three-mile radius of the old Crystal Palace which his father had watched burn down in 1936, ‘a tragic night for Sydenham, son.’ But then Stanley had no family business to take over, so had to make amends. Besides, for Henry America was the country of the past, of Custer and Wyatt Earp and Jesse James and William Bonney whose head he had cut off more than a dozen times and whose photograph – was he left-handed or had the print been made back to front? – he had shown to his father who told him: ‘That’s an Irish face. A bad Irish face, a wicked face. Never trust that sort of face, Henry – bad blood, bad genes.’

When Mr Croney came out of the pub he smelled of whisky. His friend Maureen smelled of perfume made from boiled sweets.

‘I’m more of a Mo than a Maureen.’ She squeezed on to the front bench seat between Stanley and Mr Croney. She smiled at Henry. She was no oil painting, more a distemper job. She had a puffy pub-diet complexion but was thin with it. There were the ghosts of bruises round her eyes. Her lipstick didn’t confine itself to her lips.

‘Just giving Maureen a lift home, fellers. Her mum’s come over bad.’

‘Mo.’

Henry watched her gnawed, knotted fur collar ride high over the seat back as she twisted to touch Mr Croney’s thigh. Stanley turned to Henry and winked. Mr Croney reciprocated her gesture, close to where the gear lever would have been had it not been on the steering column. Mo giggled. Henry had her straight off as a disrespectful daughter, out cavorting whilst her mother suffered stomach cramps or whatever, whilst the old lady hawked and spluttered and gasped for breath. The car crunched gravel. They were off on their mercy mission.

Mo’s way of showing proper concern for her mother seemed inappropriate to Henry. He considered that it lacked decorum. She sang. She knew all the songs. Her songbook memory stretched back to Henry’s earliest memory of what Mr Fowler called the Light Pogrom. Her voice was true, fluid, banal. She could do husky too. She loved a big, powerful, meaningful ballad. She was more herself when she was Denis Lotis or Lisa Rosa or David Whitfield than when she was Maureen nicknamed Mo.

When she was Mo she was a pub belter, so loud that Mr Croney told her to go easy for the sake of their eardrums, whereupon she exposed a wedge of slimy grey-pink mucous membrane and wiped his ear with its tip. She withdrew it into her mouth and sang ‘Que sera sera’ with a giggle. Stanley joined in: Henry felt left out, in the back – he wasn’t part of the party. He felt that even before Mo called him ‘a quiet one’ in a testily admonitory tone and Stanley neglected to speak up for him. Later, as they drove through a town with a swollen river and formal public gardens, Stanley listed for Mo what he aspired to wear: Aqua Velva, a burnt-in parting, almond-toe Densons, Cambridge-blue trousers with a fourteen-inch cuff.

‘And he wants a white mac don’t you, Stanny … That’ll turn the birds’ heads. What you think Mo?’

‘Oh it’d suit him ever so.’

Henry wondered where such sartorial licence would end. He knew, because his father had told him so, that the sort of clothes Stanley would be wearing after Christmas were wrong – which is why he kept his copy of the Denson shoes catalogue with his copies of Kamera and QT and Spick, hidden beneath toys he’d grown out of. He didn’t want to own that catalogue any more than he wanted to own those corrupting photographs – but both shoes and flesh shared a lubriciousness, both belonged to the forbidden world of sleek sinuousness. He was ashamed of his thraldom to it, of how it might taint him, of how those possessions debased him, of how they represented the threshold of sinfulness, of how they made him betray the trust of his parents. He was used to the complicity between Stanley and Mr Croney, to their familiarity: it was so unlike the proper relationship he enjoyed with his father. He envied Stanley, yet despised Mr Croney’s laxity.

It took Mr Croney a while to see Mo home once they’d stopped in a lay-by next to the woods. Her mother must have lived in a cottage in a clearing, with a little curl of smoke from its fairy-tale chimney and no road to it. Mr Croney had taken Mo’s arm as they set out on a worn path between the trees. He had held her arm to prevent her slipping on the leaves and the bony roots exhumed by years of feet. As they had vanished from view Henry had seen Mr Croney take her by the waist: he needed to support her because she was wearing stilettos and a hobble skirt like a regular piece of homework. It wasn’t the kit for a hike.

Stanley grinned: ‘That’s my mac taken care of I’d say.’ He took his father’s flask from the glove compartment. ‘Just so long as I don’t split on him to Mum … I saw a beaut with leather buttons in Wakeling’s. Swig?’

Henry shook his head. He leafed through a leatherette-bound guide to hostelries, hotels, inns, the entries annotated in Mr Croney’s hand. He was a commercial who sought bargain beds and bargain bed mates. He travelled in hosiery and jocular smut. He preyed on what Mr Fowler called the Holy Order of the Sisters of the Optics. He was a saloon-bar flatterer who gave his samples to floozies, in hope. He referred to himself as Knight of the Road.

‘He’d buy you a tie if you wanted.’ Stanley was already a future man, already drawn into men’s deceits and duplicities.

Henry replied, lamely: ‘I’ve got enough ties at the moment.’ It had not occurred to him, till Stanley made it plain, that Mr Croney was doing anything other than see the girl back to her infirm mother. To have accepted a tie would have made Henry tacitly complicit. In Henry’s family, the universe of three, bribes were not offered because there was no need, there were no secrets shared between two parties to the exclusion of the third.

Mr Croney did not possess his son’s candour. Henry saw him returning, saw him brush himself down, trying to divest himself of hanks of earth and moss and leaf meal and clinging twigs. When he realised that Henry had been watching him he said: ‘Had a fall … Slippery way … Don’t want to dirty the car.’ He was breathless, he was panting. He had to refuel with air between each lie. He gulped gusts bearing fungal spores and intimations of winter. His trouser knees were wet. His welts were encrusted. His improvisational fluency was polished: ‘Hasn’t been herself, Maureen’s mother, not since she lost her husband. Gets very browned off, it seems, down in the dumps. Takes a lot of ladies that way, their loved one passing on – your dad’d know about that … They feel at a loss – it’s rotten luck on them. And what with the winter …’ He shook his head in grave sympathy. ‘Maureen’s a good girl I’d say, tries to help the old dear keep her pecker up but the old dear’s lost her will. It’s a horrible sight lads, seeing someone wanting to do away with theirself. Tragic. Tragic. I tell you one thing Stanny – I don’t want Mum to hear about any of this. She gets most upset by any talk of suicide. It’s a woman thing and us men got to protect the womenfolk. You can bet that Henry’s dad doesn’t bring his work home, in a manner of speaking. Am I right Henry? Wouldn’t be quite nice. Not on. Mum’s touchy Stanny … They say that women never get over losing a kiddie. A little bit of them dies inside.’

They drove into the early dusk of a thick sky. The fields were flat, the earth was heavy and laden with moisture, mist hung over dully lustrous cabbage rows.

‘What,’ asked Stanley, idly, as though curiosity was merely an alleviation of boredom, ‘did she use? How did she do it? Gas oven, sleeping pills? Barbiturates? Razor in the bath Dad?’

‘You’re well up on it. You been reading a Teach Yourself? Barbiturates – I hadn’t even heard of barbiturates when I was your age. Does Mum know you know about barbiturates?’

‘Is that what it was then Dad?’ he asked sweetly.

‘Yes … Or something like them. Neighbour come by for a natter and saw her through the window. Thought she was asleep till she noticed the bottle. Had an ambulance there quick as a flash.’

‘Didn’t they take her to hospital then?’

‘She’s a veterinary nurse the neighbour. Knew the form. Fist down the neck – brought up the entire stomach contents.’

‘Must have smelled.’

‘They’re walking her round and round her little lounge – stop her nodding off. Very shaky. Keeps bumping into the furniture. And tripping over, oh what-d’you-call – hassocks. Kneelers. She embroiders them.’

Henry watched Mr Croney’s scrawny pomaded nape. He marvelled at his off-the-cuff inventiveness. It didn’t sound like a story that he was making up … it sounded plausible, credible: he wasn’t the sort to conjure veterinary nurses and embroidered hassocks out of nowhere.

Could it be that Stanley was ascribing adulterous wickedness to his father to glamorise him, to lend him a raciness that he didn’t possess? Was Stanley creating his own father, supplying him with moral deficiencies which Stanley himself hoped one day to manifest and which in the meantime gave him something to boast of in the want of anything else, such as a family business, in which to take filial pride?

Henry said nothing to his parents about the near tragedy that he had so nearly witnessed. He was loyal to Stanley and to Mr Croney and, besides, he knew the embarrassment that suicides occasioned at Fowler & Son. Their burials were grudgingly prosecuted. The specific grief prompted by such willed deaths was more than usually infected by remorseful guilt. It was the denial of fate that took the kith’n’kin so bad – that was Mr Fowler’s opinion, and he’d put on his philosophical hat to ponder the rank arrant presumption of cheating on chance. And he’d put on another hat, a black topper that shone like metal, to complain of the practical problems of a suicide’s funeral. No one enjoys them. That was trade wisdom in those days when shame and disgrace attached to the nears and dears and the welcome death stained the name of all who bore it and the deceased was a skeleton to be buried deep in the family closet and will not, please God, set a familial precedent for we know that it does run in families whether through genetic command or exemplary licence. Not that, Mr Fowler insisted to Henry, it was merely the trade which abhorred such self-abnegation but the entire Commonwealth of Her Majesty’s (the Queen’s, not the tree’s) subjects. Funeral directors do not lead the nation in matters of moral choice. They follow. That is why the state of undertaking perfectly reflects the state of society at a given moment, that is why Mr Fowler considered himself and his peers social barometers. Each year at conference, which Henry would attend from the age of fifteen, speakers would emphasise this point and append the corollary that should the day come when bodies were piled into limeless pits or left by roadsides it would be a mark of society’s decomposition and anarchy’s abominable triumph rather than a mark of the trade’s failure to resolve industrial disputes or to attract the right quality of digger. Henry didn’t know then that every trade flatters itself thus; engineers, shopkeepers, bricklayers, quantity surveyors – the state of Denmark is reflected in the state of Danish quantity surveying, now.

Chapter Two (#ulink_e62e9261-21cc-533d-8cbc-ef3fa5683bc3)

On Monday 28 October 1968 Henry Fowler, just twenty-three, twice a runner-up in the Oil Fuels Guild-sponsored Young Funeral Director of the Year competition and recently the proud bridegroom of Naomi Lewis, stood beside a Greek revival mausoleum close by the entrance to West Norwood Cemetery sniffing autumn in a pseudoacacia’s yellow leaves, musing on the greenhouse potential of the seeds in its leathery pods, never forgetting to remember that this was the eighth anniversary of Stanley Croney’s death, reflecting thereon, whistling beneath his breath a tune of his far-off teenage when he had been immature, and knew it.

Now he was a married man with hopes of fatherhood, a house with underfloor heating and a picture window which framed the gables and cupolas of houses whose inhabitants his grandfather had buried and beyond them the ordered Kentish fields where his grandfather’s father had picked hops and pears before the creation of the family business and liberation from such seasonal slavery.

Henry stood there waiting to direct a procession of Fowler & Son’s (he wasn’t the initial son in that name, that was his father, when he’d been the son – but it had passed down, and when he, Henry, had a son and his father had retired, he would be the father and so it would remain in mutating constancy). The procession of vehicles, of Rolls-Royces and Austin Sheerlines, was held up because of a traffic fatality on Beulah Hill. The deceased – the one in the coffin, not the headless motorcyclist – had been something in show business. A manager or agent or promoter – it wasn’t a world Henry Fowler was acquainted with. Though when he had visited the bereaved and the brittle bespectacled daughter who was attending her at the big house on Auckland Road he had been impressed by the number of photographs signed by stars he recognised. Charlie Drake was there, and Maureen Swanson who’d married a toff, and Al Bowlly whose death in the Blitz while Mr Fowler was stationed on the Isle of Wight denied him the opportunity of posthumously brilliantining the only crooner he’d ever met.

Henry considered mentioning this to the bereaved but the daughter would keep butting in, talking for her and, anyway, he was not certain where he stood in the debate between formality and friendliness that had riven his trade, the two sides denouncing each other as Robots and Mateys. He knew that with his blond hair, black suit and martial bearing he looked like a Robot but that his gravely worn concern for the grieving might mark him as a Matey. He kept quiet rather than risk what might be considered an unseemly disclosure.

He did suggest, however, that the cortège leaving Auckland Road should best process by way of Annerley Hill, Westow Hill and Central Hill because of the long-term roadworks and temporary traffic lights on Beulah Hill (it was these which were thought to have caused the fatal accident). But the bereaved had insisted on Beulah Hill: ‘Cyril loved it. He just loved it. He used to stand there you know and look out across Thornton Heath and Croydon and say thank God I don’t live there. You can see all the way to the downs. No, he wants to go along Beulah Hill.’

That was the Thursday.

The Sunday, Henry did his potting – black tulips (a family tradition), narcissi, three sorts of daffodil. Naomi spent the day inside acting on the precepts laid down by Consultant Jilly Morgan in an article called ‘An End To Maquillage Monotony’. When they snuggled up together on their tufty fabric sofa she was wearing oyster-pink lip gloss and Qite-A-Nite mascara. The news was cast by his favourite, though not hers, Corbett Woodall: ‘More than forty police officers, including five mounted …’

They gaped at the scenes of Grosvenor Square. There were longhairs, moustaches, police macs, police truncheons, police horses, wobbly film frames, inchoate grunts, faces of terror and hatred.

‘Vandals,’ said Henry.

‘Goths and vandals,’ said Naomi.

They agreed that should any of the Vietcong who had thrown themselves beneath the ironclad hooves of Emperor, Berty, Throckmorton, Monty and Rex II die in a South London hospital Fowler & Son would not undertake to undertake. They laughed, two as one. And that’s how undertake to undertake became a catch-phrase in their family: they were to teach it to the children, when they came along. They cuddled and they thanked each other for each other’s love and blessed presence which would endure till one of them was undertaken with due ceremony by their first-born boy, one far-off day at the other end of a fulfilling half century – at least.

Henry Fowler waited patiently as the gatehouse attendant at West Norwood Crematorium Mr Scrivenson listened agitatedly to the phone’s earpiece and plaited his nostril hair and gurned and pointed with a Capstan-strength forefinger to the handset and repeated: ‘If that’s the best ETA … if that’s the best you can do … if that’s your ETA we’re looking at a log-jam – it’s going to be Piccadi—they what? … Right you are then … Okey-dokey.’

He put down the phone, flicked at his collar and its icing of seborrhoea, the dandruff with the larger flake, rubbed his hands to say chilly, twirled a tuft of hair protruding from his phone ear, dimped a butt from his great wheel of an ashtray and said: ‘No disrespect to your dad Henry – but … Beulah Hill, I mean to say …’

‘That’s what they wanted, insisted on. Nothing to do with Dad Mr Scrivenson. Me – me. Mrs Ross has got this idea – you know, it’s a road he loved.’

‘Henry. Henry. You’re a funeral director. You direct the funeral. I dunno. Your grandad wouldn’t have stood for it. Even the best of times you got problems along Beulah Hill – there’s mineral wells there. Tarmacadam’s worst enemy. It’s why it’s always erupting. And all that subsidence in them twinky-dinky new houses. You got to learn to put your foot down – A Generation Out of Control.’

‘What?’

‘That’s what it said in the paper this morning. That’s you lot. My God.’ Mr Scrivenson stood and gaped through the dust-blasted panes. ‘You got a crow. Who’s this feller?’

‘Uh?’

‘The deceased.’

‘Mr Cyril Ross he was called. Lived in—’

‘What line?’ Mr Scrivenson looked at Henry looking blank against the dun wall of this tiny home-from-home. ‘What did he do?’

‘Some sort of show business. Agent, you know … produ—’

‘Could have told you. It’s only the theatre and the military you get crows with nowadays.’

Crow was old funerary trade slang for a mourner who dressed the part, who outdid the funeral directors in their bespokes from Kidderminster, who turned mourning into black dandyism. The blacker the garb the deeper the feeling – it’s like the paint on a Sheerline. A score of coats of jet enamel signals solemnity. Black – figurative and ceremonial uses of. That’s an area of Henry’s expertise. Henry hurried out of Scrivenson’s fug to warn the crow of the delay, inform him of its cause, apologise: ‘Excuse me sir,’ he called to the man who had his back to Henry and was scrutinising an art-nouveau headstone in the form of an escutcheon. He half turned, raising his toppered head. The crow’s garb – black barathea, black satin facings, black frogging, black moiré jabot – subjugated all individuality in the cause of ostentatious or, as Mr Fowler would have it, boastful grief. Henry was addressing a man playing a role, a machine for mourning who thanked him for the information with a nod and a tight-lipped smile. Henry turned back towards Scrivenson’s lodge. He had walked a couple of steps before he realised whom he had been talking to. Henry hurried after the crow who was alarmed by the heavy footfalls on the metalled drive.

‘I just wanted,’ Henry panted, ‘to say, if I might, how much “Teresa” meant to me you know. Well, still means to me. It’s difficult to explain – my great mucker was called Stanley.’

The crow looked even more alarmed, as though he feared Henry might assault him. ‘Stanley?’

‘Yes,’ confirmed Henry, ‘it was today he died.’

‘Today,’ echoed the crow.

‘Well, not today, today.’

‘Ah.’

‘See – I always think of you when I think of Stanley because of “Teresa”. And Jesse-Hughes.’

The crow surveyed Henry with appalled distaste: ‘Jesse-Hughes? The murderer?’

‘Oh I thought you’d have known … His last request – you must have known. I knew because of my dad but it was in the papers. Someone must have told you.’

A shake of the toppered head, a black gloved hand raised as if to silence Henry: ‘I’m sorry – I have absolutely no idea what you’re talking about.’ He tried to put a laugh in his voice.

Henry grinned come off it, mock reproachfully, wagged a conspiratorial finger. He failed to recognise that the crow regarded him as a nuisance, or worse.

‘It’s all right,’ Henry assured him, ‘it’s just we don’t get so many celebrities here – it’s not Golders Green or Putney Vale.’

‘Of course not.’

‘I just wanted to tell you, when I saw you, tell you to your face how important “Teresa” has been in my life …’

The trade never reckoned crows to be anything more than vanity and fancy cuffs. Crows were not considered to be thoughtful mourners. Nor were they reckoned passionate. No tears, no throwing themselves into the oblong hole, lest they muddy their precious clothes (not hired).

The fourth time Henry mentioned “Teresa” this one, all cold corvine politesse, turned sibilant. Every S was a venomous dart. ‘This Teresa, this woman, who is this woman?’

Henry enjoyed a spot of the old joshing. Taking the Michael (thus) was the family way. It was the lime in the mortar that bound the Fowlers. Henry would normally have reckoned the crow to be a misogynist queen because of the way he uttered woman, with contempt. But Henry knew a piss-taking joker when he met one, and he respected the ruseful stratagem, admired the implicit knowledge of the game’s rules, warmed to the deadpan performance, resolved to play along with it but could not stem his giggling as he mocked: ‘So you don’t know the handbag shop on Holloway Road then?’

The crow’s jaw plummeted on puppeteer’s wires.

‘Erherch – you didn’t know I knew about it did you urchaf? Go on – tell me that Heinz is fifty-seven varieties.’

‘Heinz? Heinz … Holloway Road … hand, handbags?’

‘That’s you,’ Henry winked, archly.

‘That’s me?’ He grimaced, a first try at a grin.

Henry was getting through. He twinkled.

But the crow shook his head in pitiful incomprehension. He turned and strode with his metal heels clicking towards the cemetery chapel.

Henry caught up with him, grasped him by the upper arm: ‘Fair’s fair, I only wanted …’

The crow jerked his arm to secure its release. And then, in an eliding gesture, he briskly flicked at Henry’s face. Henry had not been slapped since haughty Miss Gordon had grown exasperated with his inability to memorise his three-times table when he was three times three, equals nine. The crow’s black glove stung. Henry clung to his hot jowl, gaped at his antagonist like a hurt animal.

After the ceremony whilst the mourners queued in the foggy late afternoon to shake the hands of the immediately bereaved, to kiss and hug them, Mr Fowler growled from a miserly slit at one end of his mouth: ‘I want to talk to you Henry. Later.’

Henry watched dusk crêpe the headstones and the balding branches. He looked out for the crow but didn’t see him among the people who by the time they reached the two weeping ashes had ceased to be mourners and were themselves again, free once more to exclude death from their quotidian routine, a freedom which Henry rarely enjoyed, he was born to death, it was his crust. It was death that paid for the ruggedly chunky gold earrings Naomi was wearing when she said: ‘You shouldn’t put up with him Henry. Why do you put up with him?’

Mr Fowler had just left.

‘He’s my father.’

‘So what. That doesn’t mean he can just talk to you like …’

Henry looked at her so angrily. She’d never seen that before, in all their months of marriage. Henry had never tried to make her cry and now here he was, doing it with his eyes and his tight jaw when all she wanted to do was to comfort him, cuddle him better after the protracted rebukes he had received. She’d heard every word through the thin walls of their first home where there were no secrets. They lived as one. They had lived as one till he made that face at her, till he told her it was none of her business, till he accused her of eavesdropping, of spying, of covert intrusion into a private matter. It was family business.

‘I am your family too.’

That is going too far, thought Henry. That is above and beyond. ‘In a different sense,’ he sneered.

Naomi sobbed. She spoke his name, lengthened it imploringly. ‘I’m your wife Henry – that’s family.’

‘Yes, yes.’

‘And when someone speaks to you like that …’

‘Someone? Someone? You call my father someone … like, like he’d wandered in off the street. God.’

‘Henry you’re not a child. They may treat you like you’re still ten …’

‘He was right. That’s all there is to it. Nothing to do with being treated like a child. He was right. I fucked up. I am his son, and Fowler & Son does not fuck up. I was out of line. No question. He was right. So he gives me a bollocking and that’s that. I can take it. No big deal,’ he lied, stretching to save lost face with front rather than conviction. She had heard them. She had heard her husband repeat: ‘Bobby Camino … Bobby Camino … Bobby Camino …’

And she heard her father-in-law: ‘Even if he had been this Bob, Bobby … What sort of name’s that? Camino.’

‘Not his real name, Dad – Doug Truss s’matter of—’

‘I don’t care if he’s calling himself Dr Crippen and Ethel le Neve.’

‘Dad. You used to hum along to it. “Teresa, Tayrasor, Trasor, Tayrayayaysoar.” You used to sing along with me. I still got it – Top Rank.’

‘What? Henry – you’ve got to take control. He gave me his card. Norman Idmiston.’

‘It’s b’cause he was a one-hit wonder – he’s changed his name. Again.’

‘He’s a barrister. LLB, MA Oxon. Rope Court, Middle Temple.’

She heard nothing. Henry did not reply. He must have stood there with his mouth open.

‘We reflect society,’ Mr Fowler told him. ‘And I’m afraid my boy that the only section of society your behaviour this afternoon reflected was our friends the unwashed jackanapes, the great unwashed, the ingrates. The United States is our ally. You don’t burn your ally’s flag. We’d be speaking Germ—what I mean is we’ve got a lot to thank Uncle Sam for.’

‘I couldn’t agree more Dad.’

‘You’re not there as Henry Fowler, Henry. You’re there in a ritual role. Like the Queen … We have to preserve our mystery. That’ll be what shocked Mr Idmiston – not that you’d got him mixed up with this Bobby chap but that you broke the spell. That’s what it is – I’ve thought long and deep about our calling as you know Henry. And the one thing you cannot do under any circumstances is reveal what I like to call the human beneath the hat. If you were anyone else Henry you’d be looking at probation. And I’d dock your wages if you weren’t a newly married man. It’s not just Fowler & Son, it’s the whole profession – we’re butlers to the dead, we’re a caste and we stand together, abide by the caste’s code.’

‘It was wishful thinking – you know, I let it get the better of me. I suppose I must have wanted him to be Bobby Camino.’

‘You haven’t been listening have you Henry. What I’m saying is, even if this Bobby Camino does attend a funeral where you’re there in an official capacity you do not on any account go running after him asking for his autograph. Not if it’s Warren Mitchell or Dick Emery or Gerald Harper or Ted Moult you do not even if you are right about who it is. Do you read me? There’s no place for Mateys in Fowler & Son, no place whatsoever.’

‘Yeah, of course – but I wouldn’t with them anyway – it’s just that “Teresa” … It’s about Stanley. That’s what it’s about.’ And Henry Fowler hangs his head.

‘Teresa’, written by Doug Truss, Joe Meek and Mike Penny, was recorded by Joe Meek at his makeshift studio above Messrs Kaplan’s handbag-and-suitcase shop at 417 Holloway Road N7 in June 1961. Roger Laverne (né Jackson) and Heinz (Burt) played organ and bass. The record’s release on the Top Rank label was delayed because of Truss’s (Bobby Camino’s) contractual obligations to Pye.

The first time Henry Fowler and Stanley Croney heard it was shortly before noon on 28 October 1961 on the BBC Light Programme’s ‘Saturday Club’. Henry persistently opened the breakfast-room window and flapped at the air with a tooled-leather magazine holder to remove the smell of Stanley’s cigarettes – his current and last brand of choice was Kent. Henry kept an eye on where Stanley was putting his feet, shod today in mock-croc almond-toed slip-ons with a rugged buckle. He feared for the cushion tied to a ladder-back chair, he feared what his parents might say if they saw the heeled depressions in the oat fabric and if they detected the sweetish odour of the tobacco. Stanley feigned oblivion to Henry’s concern, observed that the song was ‘for kids’ even though he’d keenly beaten the table in time to the repetitive scat wail.

When the programme ended Stanley went to the toilet, so he never heard the name Jesse-Hughes. Henry, plumping the cushion flattened over two and a half decades by his father’s weight, listened to the midday news bulletin: at a special sitting of St Alban’s magistrates court a forty-three-year-old grocery company representative had been remanded in custody in connection with the murder of five women. Dudley Jesse Hughes (there was no indication that the name was primped with a hyphen) spoke only to confirm that name.

When seven months later at the Old Bailey he pronounced the sentence of death by hanging on Jesse-Hughes Lord Justice Killick ejaculated as was his wont and because it was his wont his marshal had a spare pair of slightly too-tight trousers at the ready so that when His Lordship went to dine at his club, a hank of white shirt protruded from beneath his waistcoat, from the top of his flies, prompting murmurs of approval from novice members such as Norman Idmiston.

Jesse-Hughes asked in his death cell to hear ‘Teresa’ by Bobby Camino. Teresa was the name of his poliomyelitis-stricken wife for whose sake he had polygamously married five widows in the counties of Hertfordshire, Northamptonshire (two), the Soke of Peterborough and Suffolk, had had them amend their wills in his favour and had then over twelve years killed them with atropine, in a dometic accident (shiny stair treads), by drowning (a bath, a river), and by tying a fifth, a jabbering Alzheimer, to a chair in a frosty garden for the night. It was the variety of method which according to former Reynold’s News crime reporter Claude Vange in ‘The Last Gentleman Murderer’ kept the police off his trail for so long.

Henry Fowler was to follow the case with scrupulous attention. His father joked that the judge’s black cap should be replaced by a topper because the name was a better fit! Not that Mr Fowler was pro hanging. There is, tragically, little that the embalmer can do with a roped throat. The contusions will always show through. They are the brand the hanged take to the other side. The hanged are marked with a blue-black thyroid beyond eternity – no wonder, then, that suicide in the cell the night before is so favoured an option. Henry was never sure whether Jesse-Hughes’s request to hear ‘Teresa’ was granted. He was not sure whether Jesse-Hughes had really asked for it or whether that was a journalistic fabrication. Indeed he was not even sure if he had read it or had been told it by some schoolmate (sychophant? tease?) who knew of his fondness for both case and record. He wondered how the request would have been granted. Was there an electric socket for a portable record-player in the death cell? Did Jesse-Hughes, a non-smoker with a horror of nicotine-stained fingers, succumb and smoke his first and last whilst he listened to Bobby Camino’s song about the imaginary girl who shared his crippled wife’s name?

The last cigarette that Stanley Croney smoked was an Olivier, one of a handful he had helped himself to from Mr Fowler’s EPNS cigarette box on the way back from the toilet and put in his flip-top Kent pack. He had also swallowed a draught of White & Mackay’s whisky from the bottle’s neck. When he returned to the breakfast room with one arm into a sleeve of his bronze mac Henry had switched off the radio and was wiping invisible ash from the table with his sleeve before casting his eye about the room to ensure that there was nothing for his parents to complain of. Then Henry checked his hand-me-down wallet’s contents of ten pounds, his aggregate sixteenth birthday present from three weeks previously. They left the house at 12.09 to catch a train into central London. They walked down the hill where the big Victorian mansions glared through dripping laurels and rhododendrons. Stanley, anxious about his shoes, walked on the road rather than on the pavement whose drift of wet leaves might conceal a surprise gift from a dog. They passed the forlorn park and the pavilion surrounded by scaffolding and the malnourished trees. A Kent-bound train rattled past the allotment strip where old men hid from life in huts made of doors and iron and wire and string, smoking copious weights of shag. The smoke from their makeshift chimneys was hardly distinguishable from the glary white sky. The road curved after a terrace of railway cottages, and there was the rusty old girder bridge.

Chapter Three (#ulink_0a391568-3f4c-523c-b347-57f58f917a43)

It was going on fifty feet that Stanley Croney fell. It was a seventy-foot drop to the rain-glossed cinders beside the shiny tracks that stretched into oblivion. It was almost a hundred feet high, that rusty old girder bridge. The representatives of the emergency services casually disagreed about how far the tragic lad had fallen – but who, naked eyed, can estimate height or distance with anything more than a well-meant guess when a young life has been lost and there are procedures to follow and the dense nettles on the embankment sting through uniform trousers and speed is vital because all train services have been halted. It was high, that rusty old girder bridge.

The coroner noted but did not question the disparities. He scratched at his eczematous wrists that cuffs couldn’t quite hide and listened with sterling patience to the policeman, to the ambulancemen, to the doctor, to the firemen who had surely overestimated the distance because of the duration and difficulty of their haul of the unbruised, uncut body up the steep embankment. And he had heard evidence from PC 1078 Grady in two previous cases and considered him to be a cocky smart alec and careless of details.

Thus he assumed (wrongly, as it happens) that the bridge was seventy feet above the tracks. He heard evidence from Henry Fowler; from the hairdresser Jimmy Scirea whose salon Giovanni of Mayfair Henry Fowler had run into, ‘all agitated’, asking to use the phone; from Janet Cherry who had talked to the two youths before they turned on to the bridge and who described Stanley as being ‘in a definitely frisky mood, you know, sort of excitable … show-offy – he was often like that. He was a character.’ He had performed ‘this funny bow, old-fashioned, sort of like in the olden days if you follow my meaning’. His friend, whom she knew only by sight, had merely nodded curtly and looked ostentatiously at his watch whilst she talked briefly to Stanley about a party they might both attend that night. She had been surprised not to see Stanley there because he had asked twice whether Melodie Jones would be going. ‘He was very direct. He wasn’t shy.’

Of course he wasn’t. He was a one, a daredevil, a cheeky monkey. This wasn’t the first time. Everyone can remember the early hours of New Year’s Day 1960 when after being ejected from the Man Friday Club (under age, over the limit, we’ve our licence to think of sonny) he had run up a drainpipe and had scaled a roof of the Stanley Halls and had stood silhouetted against the full-scale map of the heavens shouting to the stumbling revellers in the street below: ‘I am Stanley and this is my hall.’

He had offered variations on that boast to Henry for so long as Henry could recall. Henry’s memories of it were in his ribs. That’s where Stanley would elbow him when they walked past the Stanley Halls and Stanley Technical Trade Schools. They walked past so often that Henry suffered costal bruising from his quasi-brother’s joshing prods and proud jabs. Stanley’s identification with W.R.F. Stanley might have been founded in nothing more than the coincidence of a common name but it had grown from that frail beginning into heroic idolatry. W.R.F. was the odd one out in Stanley’s personal pantheon of sideburned rock and rollers, quiffed balladeers, d.a.’d teen idols, bostoned film actors, Brylcreemed footballers. W.R.F. was old, dead, from long ago when they wore the wrong haircuts. But, as Stanley persistently reminded Henry, he was his own creation: he had had no family business to enter, he had started from nothing and had gone so far that he had been able to buy the land and to design and build the loud structures at the bottom of South Norwood Hill. That his philanthropy was boastful is unquestionable – why else make buildings of such striking gracelessness and coarse materials if not to clamour for attention for oneself and one’s inventions.

The most celebrated of W.R.F.’s inventions was the Stanley Knife, the sine qua non of a particular sort of South London conversation. Although the plump bulk of the handle militated against the achievement of the bella figura that Stanley Croney was keen to exhibit, he invariably carried a Stanley Knife: a natty dresser needs protection against the sartorial hun. His knife was his daily link to W.R.F., to the self-made man Stanley longed to be. Stanley Croney was going to emulate him. He too would have a house like Stanleybury, he too would endow a clock tower in his native suburb to commemorate his wedding, he too was on the way to being his own man, and that meant having a way with what Mr Croney called ‘the ladies’. Henry despised Stanley’s ingratiating charm, his flimsy slimy stratagems.

He knew Janet Cherry by her loose reputation. And he despised her, and her kind, for their susceptibility to Stanley who was never at a loss for a quip. How could they fail to see through his corny ploys? How could they like someone who had no respect for them as people? Did they not realise that he was an apprentice wolf, preying? Stanley greeted her with lavish rolls of his right hand and a balletically extended leg as though he were a peruked fop, Sir Grossly Flatterwell making the first step in the immemorial dance which culminates horizontally. They had, Stanley hinted when he had observed Henry pointing to his watch and she had gone her stilettoed beehived way, already culminated. That anyway was how the virgin Henry interpreted Stanley’s ‘It’ll have to be another bite at the cherry if Melodie J doesn’t come across. Not that she won’t – she’s just rampant for it.’ It was a foreign country, yet unvisited by Henry who’d never been on a Continental holiday either.

‘And,’ Stanley went on, confidential, man of the world to a mere boy, ‘they say she gobbles.’

Henry, morose, didn’t know what Stanley meant. He was ashamed that he had not entered the carnal world of which Stanley was now a citizen. Stanley was less than six months his senior: he told himself, without conviction, that six months hence he, too, might … might what? Do wrong, that’s what he knew it to be. Premarital intercourse, as it was then known, was as wicked as electric guitars and didn’t happen to nice people, to responsible people, to people called Fowler who attended church. It was for gravediggers, not for funeral directors. It was not for those who respected their mothers, their mothers’ sex, the primacy of Christian marriage, the sanctity of the family, the notion of true love as explained by Tab Hunter who wore neither hair cream nor sideburns: ‘They say for every girl and boy in this whole world there’s just one love …’Just one love. Wait till she comes along. You’ll know it’s her. And it is invariably attended by God’s revenges of pregnancy, gonorrhoea, syphilis, gonorrhoea and syphilis (‘a royal flush’ according to sailors, and they know), social disgrace: ‘She’s had to go away’ was what Mrs Fowler said of more than one office help. If the fallen one was a cleaner who couldn’t type and wasn’t allowed to answer the phone because of her common accent she eschewed euphemism: ‘She’s gone to have an illegit. No one’ll want her now.’

This carnal world was fraught with such dangers – social, moral, irreligious, medical – that Henry Fowler was not sure he wished to enter it. Yet he was achingly jealous of Stanley who was so confident in his new knowledge, so easy with it. And he broached the subject of that evening with trepidation and with a resentment at what he knew would be Stanley’s response.

‘You … you’re going to a party then?’

‘Dave Kesteven’s sister, Sheila. Parents are away so …’

‘I thought we were going to the flicks.’

‘Yeah … look sorry. But we can go any time. Can’t we? Eh? You can come. Have a crack at the cherry – never knowingly says no.’

‘I’ll think about it,’ said Henry, meaning ‘no’.

‘Your choice.’

And here Stanley did one of his party tricks. He put his hands in his jacket pockets and turned a standing somersault. A man, obediently pushing his bicycle from the end of the pedestrians-only rusty old girder bridge gaped in astonishment then scooted with one foot on a pedal before mounting the black Hercules with calliper brakes. He has never been traced.

Henry Fowler, the only living person to have seen him, described him as ‘quite old, wearing an old man’s cap, sort of unhealthy looking, and he had this kitbag thing which was all mixed up with his cape – he had a cape like a tarpaulin and it was all bunched and sticking out funny because of the kitbag; he had cycle clips, and very big feet’.

Unhealthy, how? A sort of creamy yellow complexion. Waxy, you might say, very like some laid-out corpses. Henry Fowler, who often helped out around the family business which he would enter when he left school next summer, was well acquainted with such.

Stanley clapped his hands in self-applause, grinned madly, made Charles Atlas gestures and saluted the horizontal cape which was now astride its saddle and peddling unsteadily in the direction of the allotments. He marched from the pavement on to the rusty old girder bridge with Henry (as usual) trailing behind him. The bridge was just wide enough for three persons to walk side by side without brushing its sides, which were sheer metal sheets – those of average height had to jump to get a sight of the distant track below, a sight which would thus be retinally fixed. The bridge was lavishly riveted, the rivet heads stood proud of the metal like dugs. Each side was topped by a horizontal parapet, eight inches wide, also sewn with rivets. The flaked paint was a history of the Southern Railway’s and the Southern Region’s liveries – dun, cow brown, algae green, cream, battleship. There were crisp islets of rust, ginger Sporades which shed flakes among the puddles on the threadbare macadam of the walkway.

This is where flowers would be left for Stanley, for years to come, left to die.

The Croney family never forgot their Stanley who, larky as ever, climbed on to the parapet and walked like a tightrope artist until his smooth heel slipped on a rounded rivet head, until he stubbed his foot against an uneven joint, until he overcompensated when the friable rusty surface had him stumble, until he dropped those fifty-five or seventy or hundred feet to the cinders beside the shiny tracks below.

‘You ought,’ Stanley is now speaking his penultimate words, to the top of Henry’s head which is at the same level as his feet, ‘you really ought to come. You don’t want to worry about your wols. Everyone gets them.’ Henry’s acne, miniature crimson aureola with milk-white nipples, were his shameful secret. They were for the whole world to snigger at when his back was turned but they were, nonetheless, still a secret because they had never been mentioned – not by parents, not by brusque Dr Oxgang, not by bullies. Their existence was confined to the bathroom mirror. Now Stanley had lifted them from that plane. He had ruptured the compact between Henry and his reflection. Henry was overwhelmed by hurt.

‘Just squeeze them. That’s what I did,’ counselled Stanley, picking his way among the rivets.

Henry’s cutaneous ignominy turned to destabilising anger, to a rage as red as those aureola (let’s count them: how long have you got? No, let’s not bother), to a churning indignation. By what right? The words ‘wols’ and ‘squeeze’ echoed in his head. Friendship was suspended, blotted out. He felt a momentary resistance to his hand, he walked on, not noticing the depth of the puddles, aware of a bronze streak across the perimeter of his sinistral vision like a light flaw, deaf to the mortal howl because of the thudding clamour in his head. At the end of that moment he became aware of the absence of Stanley’s feet a few inches above him. He had gone from A (the bridge’s mid-point) to, say, D (the worn metal steps at its end) and arriving there had realised that he had no memory of B and C.

That’s when he ran, with his coat inflated by the wind. He ran to the parade of single-storey shops. He noticed how the pediment above the middle shop had lost some of its dirty white tiles, how it was an incomplete puzzle. That shop was a florist’s. There was a queue of macs and handbags which turned in unison to gesturing Henry. He stepped out as soon as he had stepped in, his nostrils gorged by funeral perfumes.

The next shop was all dead men’s clothes and their repulsive cracked shoes – you can never get the sweat out of leather, that’s undertaker lore, family wisdom. Closed, anyway, gone early for lunch, said a note taped to the door’s condensing glass. Which is why he hustled past two new hairdos with jowly flicks coming out the door of Giovanni of Mayfair and slithered down the chequered corridor flanked by the stunted cones on the heads of women who would be visitors from the Planet Kwuf. ‘Jimmy, Jimmy,’ he panted: Henry knew Jimmy Scirea because Jimmy advised the family business on dead hair and how to dress it.

Henry was all agitated. Jimmy had never seen him even mildly agitated, had always considered him a calm boy, so this was unusual. Even so Henry controlled himself enough to act with what his father counselled, with all due decorum: no ears were sheared by the sharpened scissors of the high-haired apprentices who augmented the numbers every Saturday.

They were not privy to Henry’s brief conversation with Jimmy, and Carolle the receptionist was used to Jimmy mouthing ‘Say goodbye’ and making a gesture with a flat hand across his throat when he needed the phone. There was no panic. She told her new love Salvador that she had to go and handed the apparatus to Jimmy and to the pimply boy whom she had thought at first must be the son of one of the ladies under the driers. She couldn’t help but hear the name of Stanley Croney, the beautiful boy, the cynosure of every hairdresser’s receptionist’s eyes.

Henry’s face was puffy, sweaty, tearful. There was a film of salty moisture all over its manifold eruptions, there were greasy rivulets between them like the beginnings of brooks just sprung from the earth. He rapped impatiently on the phone’s ivory-coloured handset and glared at it as though it might be faulty. He took against a fancifully framed, pertly coloured photograph of a hairdo like a chrysanthemum. He spoke, at last, in urgent bursts as though his breathing was asthmatically impaired. There was a flawed bellows in his chest.

He declined the receptionist’s offer of water. He detailed the circumstances with cursory precision. He listened intently, told the ambulance how to get to the bridge. He was calmer when he made his next call, to the police. He used the words ‘larking about, having a bit of a laugh’. He rather impertinently added: ‘Remember the traffic lights are out by the station there.’ He put down the phone, sighed, wiped his face with a paisley handkerchief, thanked the receptionist for the use of the phone and thanked Jimmy Scirea who was putting on an overcoat. Henry seemed surprised that the hairdresser should follow him from the salon. The hairdreser was in turn surprised that Henry, instead of hurrying back to the site of the accident, should amble across the road to Peattie’s bakery to buy a bag of greasy doughnuts which he began to eat with absorption as he made his way back to the bridge. He covered his face with sugar. He inspected the dense white paste. He thrust his tongue into the jammy centre. He ate as if for solace or distraction just as a smoker might draw extra keenly on a cigarette. When they reached the bridge Jimmy Scirea hauled himself on to the top of the side to look down at the body below. Then he tried to loosen a cracked fence pale to gain access to the embankment. Henry shook his head and said, with his mouth full, extruding dough, ‘Don’ rye it. Don’ bother. Bleave it to them. Too steep.’ He stuck a hand in his mouth to release his tongue from his palate. ‘Ooph – bit like having glue in your mouth but they’re very tasty. Think I’ll get some more later. Yeah definitely.’

Chapter Four (#ulink_0821d601-6334-5440-a401-65209e75d35c)

When Henry Fowler married Naomi Lewis his best man was Stanley Croney’s brother.

No, Curly didn’t forget the ring though for a moment he searched his pockets in the pretence that he had!

No, he didn’t embarrass the guests by telling off-colour gags – though he suggested that he was about to do so by talking about the day that Henry hid the salami! This, however, was merely the introduction to an anecdote about Henry removing a pork product from the table on one of Naomi’s early visits, before he realised that her family’s assimilation was such that they ignored dietary proscriptions.

‘My dad’s motto,’ Naomi never tired of explaining, ‘is – the best of both worlds, salt beef and bacon, Jewish when it suits!’ Not all of Naomi’s family and friends were as blithely indifferent to observances as she and her father were. Curly Croney was, even then, at the age of eighteen, canny enough not to stir things between the bride’s two factions. Having felt the coolness with which that allusion to the Lewises’ casual apostasy was received he made no further mention of it.

He spoke instead, with the persuasive humility which was to stand him in such favourable stead in his professional life, about his debt to his friend, the bridegroom Henry Fowler, his brother and comforter Henry Fowler, who had taken the place of his real brother Stanley. Irreplaceable Stanley – save that Henry had replaced him, as much as anyone ever could.

It was Henry who despite the almost five years’ difference in their ages had guided him through the bewilderment and grief that they had both suffered. It was Henry who had been his guiding light and mentor; he had become, as a result of a silly accident, an only child in a shattered family. And it was through Henry’s belief in the integrity and sanctity of family that the Croney family had been able to repair itself. (At this juncture Curly smiled with radiant gratitude towards the grey mutton-chop sideburns covering his father’s face and to the white miniskirt exposing his mother’s blue-veined thighs.) Henry, not least because of his own parents’ example, understood the strength of family and the importance of its perpetuation whatever losses it might suffer: a strong family is an entity which can recover from anything, and Henry had shown the way.

Curly didn’t know that Naomi’s mother had only returned to the family home in Hatch End fourteen months previously after a three-year liaison with a wallpaper salesman in Cape Town which ended when Louis died in the bedroom of a client’s house during a demonstration of new gingham prints and Louis’s daughters brought an action to remove Naomi’s mother from the green-pantiled Constantia bungalow which was now theirs. Nor did he know that fourteen of Naomi’s mother’s aunts, uncles and first cousins had died at Sobibor and Treblinka and that there is no familial recovery from such thorough murder.

But those in the Classic Rooms of the Harrow Weald Hotel that squally afternoon of 25 August 1968 who had evaded or who had survived industrial genocide were in no mood to oppose the patently decent, patently grateful young man and were inclined, too, to conjoin with him in his celebration of the tanned blond undertaker whom Naomi so obviously loved and had chosen to make her own family with far away, on the corresponding south-eastern heights of the Thames Basin – there, see them there, through the rolls of weather, places we’ve never been to, goyland, where the JC means Jesus Christ, where yarmulkes are rarely seen, where it may not even be safe to practise psychiatry, where a vocabulary of hateful epithets is nonchalantly spoken, unreproached, in the salons and golf clubs. There are sixty-five synagogues north of the Thames; there are five south of it, and about as many delis. No ritual circumcisers, either – a lack which had not even occurred to Curly Croney, which duly went unmentioned although in later years Naomi’s father, Jack Lewis, would sometimes jocularly greet Henry as ‘the man the mohel missed’. Henry took this in good spirit and was unfazed by the overintimate coarseness, because it was so obviously true – no one would expect a strapping, big-boned blond with almost Scandinavian features to have been circumcised, and, besides, his exaggerated respect for his parents extended to his parents-in-law. It was a respect which Curly illustrated by referring to an incident Naomi had mentioned to him.

On their third date, one Sunday in May, Henry had called for Naomi in his sports car and had driven her first to the Air Forces Memorial at Runnymede to admire ‘a properly tended garden of remembrance – tidiness equals respect’, then to see the brash rhododendron cliffs at Virginia Water, and on to a riverside restaurant where they ate a chateaubriand steak because it was to share and by such gestures would they unite themselves. They gazed at each other oblivious to river, weir, swans, pleasure craft, laburnums, magnolias (past their best in any case). Henry was explaining the massage procedure that must be applied to a body to alleviate rigor mortis in order to make it pliable for embalming. Naomi leaned across the table, clasped his hands and asked, poutingly, ‘Who’s your ideal woman?’

Henry was puzzled by this question. And whilst Naomi’s pose – eyes fluttering and index finger tracing the line of her lips – might have encouraged most young men to achieve the correct answer Henry contorted his face in effortful recall as though the quarry were some irrefutable slug of information like the chemical formula for formaldehyde CH

0 rather than a softly smiling ‘You’ or ‘You are’. If Henry realised that he was being asked to provide proof of the compact between them he was too shy to acknowledge it.

Suddenly his face cleared. He’s got it, she thought to herself, warm with the anticipation of an exclusive compliment. He reached inside his jacket, withdrew his wallet and removed from it a photograph which he handed to her. It showed a middle-aged woman, her face partly obscured by the hair blown across it by a gust. Naomi looked at it, as though this was some sort of trick. Then she waited for the clever pay-off.

‘That’s my mother,’ said Henry. ‘My ideal woman.’

Curly, whom Naomi regarded as a child, was blind to Naomi’s hurt when she told him of that day. He supposed that this vignette was an affirmation of her pride in her future husband’s filial loyalty and he recounted it thus, causing his audience to wonder why he should wish to slight the bride at the expense of her mother-in-law. Was he trying to ingratiate himself, in the belief that to be Jewish is to be mother fixated? Was this an expression of covert anti-Semitism? No, it was just gaucheness tempered with Curly’s steadfast idolatry of Henry. Do you know what Henry did the day after they got engaged?

The guests awaited the revelation of a passionate gesture, of some act characterised by irrationality and violins. With his father’s permission, since it was his father who had bought it for him on his twenty-first birthday, Henry traded in his two-seater, open-topped, wire-wheeled MGB for a four-seater Rover 2000 saloon ‘because we’re going to be a family and a sports car’s not suitable. Not safe either.’

‘I really liked the MG, Henry,’ murmured the bride, nuzzling her husband of an hour’s neck, ‘all that fresh air can get a girl quite excited.’

‘The Rover’s got a sun-roof,’ he replied, tersely. ‘All you’ve got to do is wind it.’

Henry had, anyway, made the right car choice in the opinion of Curly’s audience. Every one of them was beaming at him. He might not have made a theatrically romantic gesture but he had expressed a long-term commitment by buying, by investing in, a vehicle renowned for its craftsmanship and reliability, a vehicle with two extra seats to fill, in time and with God’s blessing, two extra seats which seemed to predict a nursery gurgling.

Curly finished his speech with the wish that: ‘Next time I offer a toast to these two I hope it will actually be to these three – but, for the moment, I give you Naomi and Henry.’ Naomi and Henry – their names were multiplied in the gaily decorated Classic Rooms. Curly sat down and Henry gripped him around the arm, patting his shoulder, nodding in satisfaction, a trainer whose dog has had its day. That speech had cemented their brotherhood. Naomi’s mother said what others must have thought when she muttered: ‘Who’s getting married here I want to know? Henry, ob-vi-ous-ly, but who to? I’d never heard it was the best man’s role to declare his love for the groom. What did he mean by these three? Is he expecting them to adopt him?’ And so on.

Curly would not, at that time, have admitted to loving Henry. Affection, respect, gratitude, guilt – these were the sentiments he allowed. And a sort of relief, an inchoate conviction that without someone whom he could take for granted he would not have recovered from the loss of Stanley. He did not delude himself: Henry was more of a brother to him than Stanley could ever have been, while they were young, at least, and the age gap told. He knew that had Stanley lived, reckless, selfish, apple of his father’s wandering eye, Henry would not have been his brother and that Henry would have taken no notice of him, that Henry would forever have been trailing Stanley. His guilt sprang from his having been blessed by Stanley’s death, from having been liberated by it, from having been dragged from the shadows by a true soulmate. It was as it was meant to be, according to fortuity and fatidic law. He was thankful that Henry had stuck with Stanley for all of Stanley’s life for otherwise he would not have inherited Henry. But why had Henry stuck by his childhood friend? Is friendship, too, merely a matter of habit? Was Henry so desperate that he was prepared to suffer Stanley’s routine disloyalty and infidelity? Henry was a loner, unquestionably, and not by choice: his parents’ age was, no doubt, one of the causes – they were not quite of the generation of his contemporaries’ grandparents, but they were of a generation whose children had been born before the war; Henry’s father was eighteen years older than Mr Croney whose laments for Stanley included the one that ‘we grew up alongside him’.

No mention there of Curly who had come along only five years later. Curly considered himself an afterthought. His father, besotted by Stanley who was made in his image, loved Curly when he remembered to, and when he was reminded to by his wife who clawed the smoky air as though punch drunk when she tried to beat him for his hopelessly disguised infidelities.

She wasn’t punch drunk, Mr Croney didn’t hit her, she was merely drunk, gin and sweet vermouth, so drunk that she left meat in the oven to turn to charcoal, so drunk that she lost the hang of clock time and would wake Stanley to go to school at 3 a.m. and run a bath for his little brother as soon as she had packed him out the door into the freezing fog and obfuscated sodium light, so drunk that Mr Croney grew neglectful of his excuses. He saw the error of that particular way when he returned one night to find her sober because there was no more credit at the off-licence. Her fury when in that state was focused, hurtful, shaming; he felt he had no right to be alive. So first thing in the morning he hurried to the off-licence, paid her debt and advanced the shop £30, in cash, with a wink. An investment, he said to himself, an investment – and alcoholic oblivion is a blessing to her, it helps her to forget the terrible loss of her baby and should thus be encouraged. No amount of alcohol could inhibit her breakfast screams at yet another boiled wasp preserved in a jar of plum jam.

The Fowlers’ old-fashioned house was Curly’s refuge from home, his home from home. He first came by one frosty morning six weeks after his brother’s funeral (directed by Fowler & Son) having shyly phoned to ask if he could sort through Stanley’s electric model train set which Stanley had pooled with Henry’s because the Fowler house was big enough to accommodate a permanent layout in an unheated semi-attic bedroom. The 00 ctagon of track matted with dust rested on a trestle-table along with a streaky grey aluminium control box, carriages with greasy celluloid windows, an A-4 Gresley Pacific, a Merchant Navy class locomotive, a shunter with a broken wheel, an EDL17 0–6–2 still in its royal-blue-and-white pinstriped box because by the time Stanley had been given it he was past playing with model trains. Mrs Fowler suspected that Curly, too, was past that age. She had a feeling in her waters that Curly was, though he might not know it, in search of something other than metal Dubio and plastic Tri-ang. Mrs Fowler dusted around the track, excusing her negligence, watching Curly as he picked through toys he was interested in only as souvenirs of his brother. He picked up a cream metal footbridge, fondled it with puzzled familiarity, held it out to show her.

‘That’s the bridge. It’s just like the bridge,’ he said before he wept.

She comforted him. She made him hot chocolate. She made him drop scones with honey. She held his reticent hands and hugged him. When Henry came in from work experience (at Fowler & Son) she told her son that she and Curly had just been having a little talk. Henry was startled, and it showed. They sat, the three of them, at the breakfast-room table where he had so often sat with Stanley. Mrs Fowler made a gesture to Henry, the sort of gesture a different mother might have made to her son in the presence of a girl, a nodding smile of connivance which implied more than approval, which implied a duty to go for it. So Henry suggested to Curly that they have a kick-about on the lawn. It was frosty all that day, and the ground was slippy. Neither the sixteen-year-old nor the eleven-year-old could control the old sodden ball on the crunchy grass but they played happily, in earnest, straining to tackle, diving to save, deflecting the ball off Her Majesty’s trunk, getting up a sweat and blowing white fire from their throats. When the dark came down on the garden they went inside for a tea of anchovy toast and lemon barley water.

That evening’s panel on Juke Box Jury was Jack Good, Johnny Tillotson, Helen Shapiro and, making his only appearance on the show, Bobby Camino. Curly was also a fan, and hung on every word he had to say about the Dovells’ ‘Bristol Stomp’ before he was shut out by Mr Fowler’s chortling joke that ‘They’re more like the Bristol Zoo than the Bristol Stomp. That’s hungry animals crying out to their keepers, that’s what that is.’ And Henry and Curly longed for the day when they would agree with him, without equivocation, without even a frisson of excitement at the wailing which defied propriety. That was the teatime when the Fowlers taught Curly canasta.