The Forever Whale

The Forever Whale

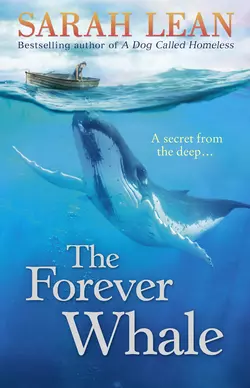

Sarah Lean

A family secret waiting to be discovered… from bestselling author of A Dog Called Homeless.A shared story can last forever.Hannah’s grandad loves telling stories from his past, but there’s one that he can’t remember… one that Hannah knows is important.When a whale appears off the coast, clues to Grandad’s secret begin to surface. Hannah is determined to solve the mystery but, as she gets closer to the truth, Grandad’s story is more extraordinary than she imagined.Includes beautiful inside artwork from hugely talented illustrator, Gary Blythe.

Praise for Sarah Lean (#ub126c2e3-acec-50b3-a8c7-c7005abc29e1)

“Sarah Lean weaves magic and emotion into beautiful stories.”

Cathy Cassidy

“Touching, reflective and lyrical.” Culture supplement,

The Sunday Times

“… beautifully written and moving. A talent to watch.”

The Bookseller

“Sarah Lean’s graceful, miraculous writing will have you weeping one moment and rejoicing the next.”

Katherine Applegate, author of The One and Only Ivan

For Edward, who filmed our home and showed me his point of view … and the cat’s

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u674d538f-d523-591a-bb97-ff920fe6e2fd)

Praise for Sarah Lean

Dedication (#uc8365edd-63da-581d-b868-5b0f87e3e92d)

Chapter 1 (#u7383cd6e-4fac-58ef-9a6c-7a469d92cebe)

Chapter 2 (#u3bfed8d5-04d9-5147-83b4-7b5560e276a2)

Chapter 3 (#ufe5e7a8b-3ce2-52e5-bda3-369429b5882f)

Chapter 4 (#ude8ac76e-27c3-5c02-bf47-77188ef03b53)

Chapter 5 (#u84293276-6f16-562a-a1dc-24dad5a3c0e0)

Chapter 6 (#u42039b23-d271-5f16-a435-b97e323a190e)

Chapter 7 (#u5edcca30-ac86-5a6e-ba5c-a291e7b8c589)

Chapter 8 (#u8afc03a1-2a26-5ed7-bd99-2a3c5a288f95)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Books by Sarah Lean (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1.

GRANDAD DRAWS THE OARS INTO THE BOAT as we coast on the glassy water until we nudge into the bank. We both have our fingers over our lips, not to tell each other to be quiet, because we are, but because we think alike. I don’t know what Grandad has seen, I only know to trust him.

“Can you see it, Hannah?” Grandad whispers.

The dappled and striped shadows are barely moving in the golden September evening and I can’t see anything in the jumble of grasses and reeds. I shake my head.

“Keep looking,” Grandad whispers.

I follow his eyes, but it takes me a long while to spot the fawn, curled up and waiting. Its skin is hardly any different from the landscape around it. I can see the glisten of its black nose, but it knows to stay still, to be safe. Once I see it, it stands out a mile.

I whisper, “Is the fawn all right on its own, Grandad?”

He nods his head towards another curve of the bank. A deer is looking at us, anxious because she doesn’t want to draw attention to her fawn, who is separated from her by a channel of water.

Grandad smiles to himself. “Will you stay or will you swim across?” He says it as if he and the deer have a history together. We’ve seen deer here many times, but he’s never said that before.

“I didn’t know deer could swim,” I say, keeping my voice low and soft like his.

“That’s how they came to live on …” Grandad hesitates and looks over his shoulder. His eyebrows are crushed into a frown. He’s looking towards the island in the middle of the huge harbour, even though we can barely see it from here. But I’m not sure why.

“Furze Island?” I ask.

“Furze Island,” he repeats. “A long time ago a herd of deer swam over from the mainland and settled on the island.”

Grandad is still looking far away towards the harbour entrance, maybe for the billow of sails, to see if any broad and magnificent ships have blown in today.

We are quiet for a few minutes until Grandad speaks again. “It’s your turn to row now,” he says.

We change places in the boat. I see him stumble. He must be tired today. Grandad and I have taken a thousand journeys like this out in the quiet inlets of the harbour. Here we are just specks, tiny people marvelling at the changing sea and all the ordinary everyday things. These are my favourite days. I feel the familiar tug in my middle as the oars knock in their sockets and I row, pulling, rolling and lifting like Grandad taught me. The paddles splash like a slow-ticking clock.

“Hannah, I want you to remember something for me,” Grandad says. “Something important, in case I forget.”

I wonder why he would ever forget something important, but I want him to tell me.

“Anything for you,” I say.

“August the eighteenth,” he says. “You’ll remind me, won’t you?”

“That’s a long time away, nearly a year. Are you going somewhere?”

I only ask because I know that Grandad has spent all his life here in Hambourne, working with wood, rowing the inlets with me, and watching from his bedroom window for schooners and square-riggers in the harbour.

Grandad leans against the side of the boat and scratches his white beard and the bristles crackle under his fingernails. His eyes are warm and brown like oiled wood.

“Some journeys need us to travel great distances. But others are closer to home, like today when our eyes see more than what’s in front of us.”

“You mean like finding the fawn in the grass?” I see his face folding like worn origami paper into the peaceful shape I’ve always known.

Grandad slowly puts his gnarly old hand on the bench between us. My hand is still smooth like a map without journeys and I put it on top of his. We pile our hands over each other, his then mine, his then mine, like we always have. He pulls his huge hands out and gathers mine like an apple in his. And, just like always, that feeling is too big to keep inside me and bursts out and makes me laugh.

“Yes, great journeys like this,” he says. “Those great days that live in our memories and make us who we are.”

I’m not sure I exactly understand what he means. I just see something in him and I want to be like him too. Somewhere there in his sun-baked skin is a map of everything that made him who he is.

“Can I come with you on August the eighteenth, Grandad? I want to see what you’ve seen.”

Grandad’s ancient smile fills his cheeks and his eyes and I think of his face as a whole life-full of memories.

“It’s all right here.” His huge hand is over his chest. “The greatest power on earth. Remember, you have to think big, Hannah, and when things are good, think bigger.”

Grandad moved in with us after Grandma died ten years ago. I wasn’t exactly here then, still wriggling and growing into a baby inside my mum, but our home was his before it was mine. Grandad hadn’t liked to live alone and Mum hadn’t wanted him to live alone either. Grandma, who I never met, had done everything for him. She’d pressed his shirts and cooked his tea and put a cushion behind his head when he fell asleep in the chair. Even though he could have done all of these things for himself, she’d thought of him before she did anything.

I’m named after her. She was Hannah Jenkins, I’m Hannah Gray, and in lots of ways I’m like her.

Just then a voice calls across the water. Dad is waiting for us on the slope at Gorbreen slipway. It’s late, he’s saying; he’s telling us to come ashore.

I pull on one oar to steer us in.

Dad steadies Grandad as he climbs out and tells Grandad he should sit in the car, but he stays by the slipway and stares out to the harbour again. Dad and I roll the trailer under the boat. We pull it up the slipway and I leave Dad to hitch it to the car.

I stand beside Grandad and wonder why he’s not getting in the car.

“I think it’s time to put the boat away for the winter, Hannah,” he says.

I know this means we won’t go out rowing again until next spring.

A curlew is singing, and it’s soft and eerie, filling the bay and my ears.

“Grandad, tell me more about the deer,” I say.

Grandad nods and smiles, but he’s looking at the footprints of seabirds pressed in the soft muddy bank. They’ll be washed away when the tide comes in and draws out again.

“Come on, you two,” Dad calls. “Time to go.”

There’s a long moment before we go, when I see into Grandad’s warm eyes and he says, “I have quite a story I’m saving to tell you about the deer.” He says it quietly so only I hear his deep voice through the curlew’s song.

“Remember August the eighteenth,” he says again. “And one day, I hope you’ll go on the journey and see what I saw.”

2.

“READY FOR SOME TOAST, GRANDAD?”

Grandad likes his toast cooked under the gas grill so it’s dark brown with charcoal around the edge.

“I’ve got it,” I say because Grandad is staring blankly at the kitchen cupboards. I’ve already found the bread knife and cut an extra piece of bread as always.

“Watch the toast a minute,” I say and go outside to feed the birds.

Every morning I still try to do what Grandad and I have always done because it’s helping his memory stay alive. We haven’t been out in the boat again for nearly a year, but there are lots of other everyday things that we’ve always shared. Our early mornings are special, even though things are not exactly the same as they used to be.

Grandad has Alzheimer’s disease. One moment he is as he’s always been, wise and knowing and safe. Sometimes his memory fades like a ship disappearing into a sea mist.

Alzheimer’s usually picks on older people, but it’s not fussy about things like how big or bold a person is, or how important they are to their granddaughter. It’s taking all the things Grandad learned, all the things he saw and heard, all the things he loved. Alzheimer’s is a history thief, stealing his past and our future together.

The hedges shiver with excited twittering as I sprinkle the crusts on the lawn and as soon as I step back the sparrows get busy with the crumbs. I turn the earth with the garden fork that Grandad always leaves there. The robin comes and perches on the fork handle and watches the soil for the wriggle of a worm or centipede. Grandad once said that an ounce of brown and red feathers didn’t seem like much, but it’s the robin’s nature to be fierce like a tiger when it protects its territory. He likes the robin most of all.

I water our sunflowers. They’re taller than me, but the heads are still fresh and green. I can remember Grandad and I crouched in our wellies the first time we grew them. He’d shown me some small black and white striped seeds, shaped like miniature rowing boats.

“See this tiny little package?” he’d said, drawing away one of the seeds with his fingertip. “All it needs is water and the sun and in a few short months it will become a giant. And, when it’s a giant, it will have its own tiny seeds and each one can become a giant too.”

“Like it goes on forever?” I’d said.

“Just like that, only in a new plant.”

We’d pressed our seeds into pots of compost and I waited for them to grow. I hadn’t known what to expect and asked him every day when I came back from school where the giants were. Until I saw them for myself.

But even when the leaves turned dark and the stalks were thick with sap and towered over me, I still had to wait for the new seeds to ripen so that we could store them and then, the following spring, press them into the compost to grow once again.

Grandad follows me outside. I notice he doesn’t have his slippers on, but it doesn’t matter because the June summer ground is dry and warm.

I’ve asked Grandad the same question every day for years, even though I know the answer. I ask him again now: “When will the sunflower seeds be ready?” But this is the first morning he doesn’t reply. I say it for him: “When the hearts are golden,” so that one of us remembers.

Grandad nods towards the hard shadow of the fence in the far corner of our garden where a cat is twitching its tail. He struggles to remember the cat’s name.

“It’s Smokey,” I say, even though I’m sure Grandad will remember in a minute.

“Yes, that’s it,” he says. “We can try and keep the birds safe from him, but Smokey can’t help being a dog.”

I know Grandad meant to say cat not dog. Sometimes the Alzheimer’s makes him muddle things up, but I usually know what he means.

Smokey is a clever grey cat, and I’ve seen him catch baby sparrows before. Even though Mrs Simm gives him plenty of food, Smokey will take a bird if he wants to. I think of Smokey like he’s Alzheimer’s disease, creeping in and stealing things that don’t belong to him.

I hiss and Smokey scrabbles over the fence.

Grandad opens the garage door and he’s trying to untie the tarpaulin over his boat.

“Fair and fine today,” he smiles. “Shall we launch at Gorbreen?”

I don’t remind him we haven’t been in the boat since we put it away at the end of last September. I don’t tell him Dad won’t let us go out any more. “I’ll sort the boat out, Grandad. We could go and see the deer again.” And I lead him away, back into the garden.

“Grandad? Remember you were going to tell me a story?” I say. He doesn’t reply. An ocean of nothing washes into his eyes. “A story about the deer? About a journey?”

This isn’t the first time I’ve asked him. It isn’t the first time I’ve reminded him of the months passing. August 18th is now only eight weeks away.

“Journey?” he says. “Where are we going?”

Suddenly the smoke alarm shrills from the kitchen.

“Grandad, the toast!”

I run back inside. Smoke curls out of the grill and rolls up to the ceiling. I turn off the gas, climb on to the kitchen table and jump up to try to turn the alarm off before anyone else comes down for breakfast, but I’m not tall enough to reach.

Mum runs down the stairs. She stands on a chair and pokes at the alarm with a broom handle until it stops shrieking.

“Watch what Grandad’s doing, please,” Mum whispers as we try to wave the smoke away with tea towels.

“It was just an accident,” I say when Dad comes in.

Dad looks out at Grandad in the garden and I know what he’s thinking.

“It’s my fault,” I say. “I was feeding the birds and chasing Smokey away and watering the sunflowers and I forgot about the breakfast.”

“Sounds like you’ve had a busy morning,” Dad says.

He opens the fridge to get some juice and finds his car keys in there. He takes them out and bounces them up and down in his hand.

“Will you put those boxes by the front door into the car?” Mum says to Dad. “I’ll be along in a minute.” He and Mum share a long look before Mum says to him, “We’ll talk later.”

“Save some energy for school, Hannah,” Dad says on his way out.

Grandad comes into the kitchen. He opens the cupboard under the sink and pulls out a bag of birdseed. He doesn’t say anything about the smoke and the toast, he doesn’t close the cupboard door and the bag of seed is tipping from his hands.

“Grandad,” Mum says, “they’re spilling and going everywhere!” Dots of seed bounce up from the tiled floor around his feet. “Grandad?”

Grandad doesn’t seem to hear her and shuffles back outside, leaving a trail of seeds behind him. I hear the sparrows twittering, waiting for him.

“How is he this morning?” Mum says, sniffing at the bitter smell of burnt toast on her sleeve.

“He’s fine,” I say. “I heard him get up in the night so he’s probably just tired.” Mum frowns. “I can sweep that up,” I say, jumping down and reaching for the broom.

Mum holds on to the handle for a moment. “Hannah …” she says, but I don’t want her to say what everybody in our house has been saying recently, that they’re worried about the way Grandad is behaving.

“He’s fine,” I say again. “I forgot about the toast. It’s my fault.”

Mum sighs a little and says, “Go and help Grandad, love.”

“Mum!” I point to the toast on fire in the cooker behind her.

Mum steps down from the chair and uses the barbecue tongs to pick up the flaming toast and fling it out of the back door, and while she isn’t looking I close the door to the cupboard under the sink because I’ve noticed that there are things inside it that shouldn’t be there.

3.

“WHAT WAS THAT ALL ABOUT?” MY SISTER JODIE says, when Mum has gone to work. “And what’s that disgusting smell?”

I’m on the floor with a brush, but the seeds keep bouncing back out of the dustpan.

“I forgot to watch the toast,” I mutter.

Jodie pretends she doesn’t see me sweep some of the seeds under the doormat.

“Why don’t you just use the toaster like everyone else?” she says, painting gloss on her lips.

I bite my teeth together. “Why can’t Grandad have it how he likes it?”

Jodie doesn’t say anything. She’s more interested in smudging her lips and watching her reflection on the edge of the cooker.

“Why are you putting on lipgloss before you’ve had your breakfast?” I say.

She rolls her eyes and pours some cereal and milk and mutters to herself, “Where’s he put the sugar bowl now?”

Jodie sighs and goes out of the kitchen because the last time the bowl wasn’t by the kettle we eventually found it in a drawer in the sitting room. These things are Alzheimer’s fault, not Grandad’s.

I crawl across the floor and open the cupboard under the sink. It smells of damp. The sugar bowl is there, but it has tipped over the bags and bags of birdseed stuffed inside. I think about putting the bowl over by the kettle, but Jodie has come back and is watching me.

“What’s that in there?” she says.

I close the door, but Jodie comes over, so I push her away and sit with my back against the cupboard door with my arms folded and my legs crossed.

“Actually, this is my place for hiding private things,” I tell her, “so leave them alone.”

She stands with her legs either side of me and I make myself go all stiff, but it doesn’t work because she’s fifteen and five years bigger and stronger than me.

“Don’t be a baby,” Jodie says.

She holds my elbows, pulls me away and opens the door. She finds an old tube of sparkly lipstick, Grandad’s slippers and one of her books that went missing a few weeks ago. She leaves the cupboard door open and slides down to the floor, wiping sticky sugar crystals from her lipstick.

“I put those things in there when I was sweeping,” I say.

She holds the book in front of my face. The damp pages bulge.

“Sure you did.” Jodie twitches her mouth to the side. “I know what you’re trying to do, but it’s not like we don’t all know Grandad’s getting worse.”

I grit my teeth again and then take a minute because I want Jodie on my side. “I notice things more than anyone else. He’s tired today, that’s all. Can’t he just have a bad day like everyone else? He’ll be fine later, you’ll see.”

Jodie twiddles with her hair and we sit in silence with my words still echoing in my own ears because I know they’re not true. It’s what I want to believe though.

Jodie reaches inside the cupboard and finds four bars of chocolate.

“Grandad’s still hiding his chocolate, like a squirrel hides nuts for the winter,” she says. She doesn’t want to fight either. “Even before he got Alzheimer’s he’d forget where he put it.”

“Remember that time I ate so much of Grandad’s chocolate that I was sick?” I say.

We laugh quietly together.

I remember that night when Jodie and I had snuck around the house with a torch to look for Grandad’s hidden chocolate. We’d found loads and then hidden under the kitchen table. I ate far too much. Jodie knocked on Grandad’s bedroom door because we knew Mum and Dad would make a fuss, but Grandad would just put things right. He’d sent Jodie to bed and sat me on his lap in his high-backed chair with a bowl and a towel until I felt better.

“Did you know your grandma liked chocolate when she was a little girl?” he’d asked me as he wrapped us both in a blanket and took the bowl away from under my chin.

I shook my head through my tears. He smiled and his eyes crinkled.

“She had a sweet tooth like you, that’s why I’ve always had to hide my chocolate.”

“Did you marry her when she was a little girl?” I sniffed.

He chuckled quietly. “No, but even then I knew she was the girl for me.”

“How did you know?” I’d asked. He rubbed my back and I felt the sickness going and sleep on its way.

“How did I know? Well, that’s simple. Because something great put us together, bound us together forever, and it will never be undone.”

I remember tucking my head into his shoulder.

“What was the great thing?”

I remember feeling his wide chest heave as he took in a giant breath. I remember the dark and the quiet and the glimmer of light from the hall. I remember him saying, “Another time. Go to sleep now, little Hannah.”

4.

JODIE NUDGES ME. “HELLO? WHERE WERE YOU?”

I was thinking about the story Grandad had been meaning to tell me, wondering if it had anything to do with Grandma. I want him to remember because August 18th is getting closer, but no matter how many times I’ve said it, he doesn’t know why he asked me to remind him. None of us have birthdays on that day, no anniversaries, nothing like that, I checked. I think it must be to do with a memory Grandad has, something important that scoops him up and takes him back to another time so he can feel those things that happened all over again.

I think of how important it is for all of us, but especially for Grandad, to remember the bright things from the past. There must have been so many of them to make him so special, or maybe just one extraordinary thing. I hate that Alzheimer’s doesn’t always let him go back to times and places he loved the most, when I can, just like that, if I want to.

I’m still on the kitchen floor with Jodie.

“Do you remember Grandma?” I ask her.

“Not much.” Jodie looks disappointed with herself for a moment. “She had soft cheeks, that’s what I remember, and she always had toffees in her cardigan pocket. You could hear the papers rustling.” She pinches my cheek and pushes a chocolate bar into my hands. “You’re little and soft like Grandma was,” she smiles.

Grandad comes into the kitchen. “Time for breakfast,” he says.

“I’ll make you some more toast, Grandad,” I say.

I cut some more bread, put it in the toaster this time and turn the timer up high.

“My class is going on a field trip down to the quay today,” I tell him as we sit to eat our toast. “The mayor is unveiling a statue of a lifeboat. They’ve put a big cover over it so nobody can see it until today. Would you like to go down at the weekend and see it too?”

Slowly Grandad turns towards me. “We’ll hide my boat at Hambourne where nobody will find it.”

Right then I feel as if I’m on my own in the boat at sea, and I can’t see solid land on the horizon, and there’s nowhere safe to go. I’m about to tell Grandad that his boat is in the garage, but sometimes when I correct what he says he gets confused and I don’t want to upset him.

The dark edges of his toast crumble and fall into his lap. He doesn’t notice.

“Hannah,” Jodie says, breaking the uncomfortable silence, “we’d better get going.”

She picks up her bulging book and some photographs fall out from between the pages and scatter on the table. Three are of my grandma, Hannah Jenkins, who I never knew; three are of me, Hannah Gray. All of the photos are rippled and flaking from the dampness in the cupboard.

Grandad’s eyebrows furrow as we all look at the photos.

“Where’s Hannah?” he says. “I haven’t seen her this morning.”

Jodie stares at me, chewing the pad of her thumb. I try to hide what feels like a stone dropping in my stomach. She doesn’t say what I know she’s thinking, that neither of us knows whether he’s forgotten that Grandma died over ten years ago or if he’s now starting to forget me.

Jodie goes to the front door, but I can’t leave, not yet. I want to believe that when I come back this afternoon Grandad will be as he always was. I lean my hand on the table and kiss the white beard on his cheek.

“We’re going to school now,” I say.

His eyes brighten for a moment and he doesn’t know what he’s just said, but I see something unfamiliar in his face.

“Grandad, please remember the story you were going to tell me. About the deer, about a journey. It’ll be August the eighteenth soon.”

His eyes flicker as if he’s searching for something. He rubs his beard and I hear the bristles. I see brightness in his eyes, as if he’s found something.

“Hannah!” Jodie calls. “We’re going to be late!”

Grandad moves his hand and mine disappears underneath his.

“It’s quite a story, Hannah, about the greatest power on earth.”

I’m not sure if we can wait until August.

“Hannah, you have to come now!” Jodie shouts.

“Tell me about it after school, Grandad,” I say and kiss him again. “Today!”

“Today, after school, I’ll be waiting,” he says. “Let’s see if we can find that whale.”

“A whale?” I say, but Jodie has come back in and is dragging me away. “A whale, Grandad?” I call.

“Don’t forget,” I hear him say.

5.

THE MAYOR’S GOLD CHAIN LOOKS HEAVY, AND AT last he stops talking to the crowd and holds up a huge pair of scissors to cut the red ribbon around the statue. Four people are behind him, holding the corners of a big shiny black sheet so nobody can see what’s underneath.

Josh Beale makes a noise like he’s dying for some unknown reason, so our teacher tells him to shush, but he carries on gargling. I want to blank him out because I’m trying to think about what Grandad said this morning. I thought he wanted to tell me an important story about the deer, but he said we were going to find a whale. I don’t understand. I’m thinking about how Alzheimer’s disease is making me confused too.

A photographer from the local paper tells the mayor to wait a minute.

“Can we have some kids from the local school up there as well?” he says. “And a teacher.”

I am one of the children who get picked and we line up either side of the mayor and pretend we’re helping to hold the ribbon.

Everyone counts down, three, two, one. The scissors snip.

The four people let go of the cover and it billows above our heads, puffed up by the sea breeze. I feel the cool shadow over me as it ripples over our heads, falls and shrouds us. For a second the world goes dark and I smell something metallic. The people who were holding on to the cover drag it away again and everything seems just as it was. The crowd gasp then clap, but I have a funny feeling, like someone is standing behind me.

I turn round. The life-size statue is of a smooth golden-bronze figure, with no nose or eyes or mouth. It is leaning over the bow of a boat and reaching an arm to someone who is in the sea who doesn’t have a proper face either.

“Hey, you, little girl,” the photographer says, “look this way. Everyone smile.”

I can’t stop looking at the statue of the people with no faces. I see how hard the person in the boat is reaching for the one lost at sea.

I nudge Linus Drew who is standing next to me.

“Who is it?” I ask him.

“Who’s who?” he says.

“The statues. How are we supposed to know who they are if they don’t have faces?”

Linus shrugs, which is what he does a lot of the time. Our teacher hears me.

“They represent anyone,” Mrs Gooch says. “We’ll be talking about it later in class and reflecting on what we feel about the statue.”

I think of Grandad and how this morning he looked at me but didn’t see me. It feels like the shadow of the black cover is still over me.

“Anyone?” I say, catching Mrs Gooch’s arm. “How can a person be anyone? Surely they have to be someone?”

“Well, yes, that’s a good question, but this is art, Hannah, so there might be lots of possible meanings. Maybe we can find something of ourselves in it.” Mrs Gooch waits for me to say something. “Is everything all right?” she asks.

I nod. But it’s not true. Everything isn’t all right and I want to talk about it, but I’ve not told anyone that my grandad has Alzheimer’s. All my friends know him because of all the years he used to take me to and from school. He was the BFG at the school gates who lifted us up high in his arms and asked us to tell him what we’d been doing that day. I had told my friends Grandad didn’t come any more because we’d got too big and because I could walk to school on my own now.

Alzheimer’s isn’t like a broken leg or the flu; it’s buried in someone’s brain. You can’t see it. You just notice what’s missing. People don’t like it when it’s something to do with brains and not being normal.

We line up to go back to school and I’m partnered with my friend Megan. Mrs Gooch walks beside us.

“Megan?” Mrs Gooch says. “What did you think of the statue?”

“I thought it was nice because it’s to remember all the people who helped save lives at sea,” Megan says.

“Yes, it is. And how does it make you feel?”

I’m listening, but I don’t really want to join in now.

“I feel … like it’s good that we have people who will help us if we need them. And,” Megan continues, “it reminds me that I have to wear a life jacket when we go out in my uncle’s boat.”

“So it also reminds you of something to do with yourself. What about you, Hannah?” Mrs Gooch says. I look back at the statue, at the people who could be anyone.

“I don’t like that they don’t have names,” I say. “I want to know who they are.”

Is it just my name that Grandad is forgetting? Or is it much more than that? What about all our journeys in his boat, all our thousands of mornings, our talks, all the things that tie us together? Will he remember the story? Will he remember me when I get home?

6.

“GRANDAD?” I CALL AFTER SCHOOL, WHILE I FLICK on the kettle for him. I’m still thinking about the statue on the quay. Mrs Gooch said we could all try and find something of ourselves in the statue, but I’m thinking of Grandad instead.

The back door is open. At first I think I see ashes outside on the patio, and I remember the burnt toast from this morning. But they aren’t ashes. They’re tiny red and brown feathers.

My stomach turns to stone. I call Grandad’s name and run upstairs and look in all the rooms, but I’m already thinking that Smokey wouldn’t dare come so close to the house to take a bird if Grandad was here.

I come back to the kitchen. Grandad’s newspaper isn’t on the table.

Grandad doesn’t walk as well as he did, but most days he used to go as far as the shop down Southbrook Hill to get a bar of chocolate and a newspaper and some birdseed. On the way to the shop he’d stop to talk to Mr Howard who clips his box hedges with tiny shears into Christmas puddings and cones and clouds.

I run down the street. Mr Howard is clipping his hedge as usual.

“Have you seen my grandad today?” I call.

“Yes, he was headed thataway.” Mr Howard points with his sharp snippers towards Southbrook Hill. “I wished him a good afternoon, but he walked past without so much as a friendly word. I told him he looked a little peaky, but … well, that was nearly an hour ago.”

I am already running towards the hill.

Grandad isn’t at the shop. Suddenly my mind is racing, thinking of how he was when I left this morning. Had he heard me after all? Would he have gone to see the statue at the quay by himself? I take the road that leads down to the old town.

Papers rustle and tumble along the cobbled street, blown by the sea breeze coming through an alleyway between the shops. At the end of the alleyway I stop to catch my breath and look both ways. I hear boat masts clanking along the quay like alarms. In the distance I see Grandad shuffling unsteadily away from the new statue towards Hambourne slipway. I keep running.

Coming towards Grandad from the opposite direction I see Megan, Josh and Linus, who is on his scooter. As they pass Grandad, they speak to him. Megan watches over her shoulder, but Grandad doesn’t turn round so she stops and walks back to him. He looks down at the slipway, then out to sea.

“Grandad?” I call as I reach him. “What are you doing here?”

I hook my arm through his. He looks down at his other clenched hand. The ocean of nothing is in his eyes.

“Come on,” I say. “You’ve walked all the way to Hambourne slipway. Let’s go home now.”

I try to lead him away, but his arm is heavy. Megan, Josh and Linus stand uncomfortably nearby. “What’s wrong with him?” I hear Josh say to Linus.

“Grandad?” I say. “Let’s walk home together.”

“Do you want us to go?” Megan says.

But they don’t go and I can’t think what to do.

“Mr Jenkins,” Linus says. “Hannah and me will walk you home.”

Linus lays down his scooter and tries to take Grandad’s other arm.

“This way,” he says, but Grandad trembles.

“Grandad, please, it’s me, Hannah,” I say as a tear falls from his eye. “You’re safe.”

“Shall I get someone to help?” Megan says.

He’s fine, I want to say. But I see the unstoppable grey-green tide rushing away from the slipway steps, in the same way that Alzheimer’s is dragging Grandad away from me. Grandad doesn’t know who I am.

“Grandad, it’s me, Hannah. Remember, we’re going to go on a journey?”

I see a flicker in Grandad’s eyes. “The whale … it’s coming,” he says. He tries to speak again, but a sore groan comes from his lopsided mouth. He opens his hand.

Josh jumps back and falls over Linus’s scooter, tearing his knees on the pavement. Megan gasps and backs away. Only Linus stays beside me and stares at the robin, at the ounce of lifeless feathers in Grandad’s hands.

7.

“HOW LONG WILL GRANDAD BE IN HOSPITAL?” Jodie says that night.

It was a stroke that took a whole chunk more of Grandad away from us. The blood supply to his brain had been interrupted and more brain cells had died. It made the symptoms of Alzheimer’s worse, like he’d jumped down a whole staircase instead of taking the disease step by step.

Mum shakes her head. “We don’t know, love. He’s going to need some help to get him back on his feet again.”

“And then he’s coming home,” I say, “so that I can look after him.”

Mum and Dad glance sideways at each other.

“We’re not sure what the process is just yet,” Dad says. “Grandad is going to need a lot of therapy over the next few months—”

“Months?” I ask. He can’t be in hospital for months. I have to remind him of August 18th. I have to know what the story is so that we can go on our journey together.

“Weeks,” Mum says, “it might only be weeks.” Again she glances at Dad.

“Did Grandad say anything?” I ask. “Anything about me or anything at all?”

Mum shakes her head. “I don’t know if he knew it was me,” she says quietly. “I don’t think he recognised either of us.”

I push between Mum and Dad on the sofa, the only space I can see that feels safe.

“Can we visit him?” Jodie says, squeezing on the other side of Mum.

“Not just yet,” Dad says.

Mum touches Dad’s arm. “He’s very confused and weak at the moment,” she says. “I’ll go in tomorrow to check how he is and let you all know. Then we’ll see when he’s up to having more visitors.”

We know that nobody gets better from Alzheimer’s, but the doctor said it’s possible Grandad can recover from some of the symptoms of the stroke. But the way Mum described him sounded all wrong, like it was someone else in hospital, not my grandad. I keep thinking he’s still here, somewhere, only I can’t find him.

I get up from the sofa.

“I don’t want to see him in hospital,” I say. “But when he comes home, there’s something we have to do.”

“What’s that?” asks Dad.

They all look at me and I’m not sure now how to say what I’m thinking. Our journeys were about being together and discovering things, and seeing the world in front of us with bright eyes and open ears. I was going to take him out in the boat again. We wouldn’t go far – we’d stay in the inlets and quiet harbour waters. Because I’m sure, if we did, he’d remember everything he wanted to tell me.

“We’re going to take a journey together,” I say, but don’t wait for them to ask questions because I can’t explain anything more. How can I tell them that I think we’re going to find a whale?

I go out to the kitchen and rummage through the cupboards until I find the spray gun. I fill the bottle with cold water from the tap. I go out to the garden and shout into the night shadows, “Just you wait until Grandad gets back, Smokey! I know it was you that killed the robin.”

8.

“DID YOU THINK SOMETHING WAS WRONG WITH Grandad yesterday morning?” Jodie says when I meet her on the quay the next day on the way home from school.

I feel guilty because I’ve been trying to cover up some of the things he did, and maybe I shouldn’t have done that.

“Yes, but most of the time he was fine,” I say. It’s an effort to lie and makes my stomach hurt. “I wanted him to be fine,” I say quietly.

Jodie knows I feel bad and I can trust her not to make me feel worse.

We stare at the statue of the faceless people.

“It’s weird how they didn’t give them faces,” Jodie says.

“Mrs Gooch said it’s so we can all see something of ourselves in them.”

Jodie pulls a face and I know what she’s thinking. Nobody’s faces are the same – they have different shapes and colours and ways that they are put together.

“It’s not like a mirror or anything,” I say. “It’s just that it’s supposed to remind us of things like being safe or rescued or people we know, something like that.”

I see Grandad and me in the statue. He’s the big brave figure in the boat reaching for the small one, to carry them safely back to shore.

“What’s the greatest power on earth, Jodie?”

“That sounds like something Grandad would say.”

“It is something he said, ages ago. He was going to tell me a story … about a journey.”

Jodie screws up her face and tips her head to the side. “Maybe the greatest power on earth is Art,” she says, taking a long look at the statue. “But not this bit of art. It’s weird.”

I notice Jodie has black eyeliner and mascara and her lips are glossy and pink.

“Have you got a boyfriend?” I say.

“No!” she says, far too strongly.

“Thought so. You don’t normally wear so much make-up. What’s your boyfriend’s name?”

“He’s not my boyfriend,” she says, “I just like him.”

“How much?”

Jodie’s painted eyes open wider.

“Loads,” she says which makes us smile, but our faces drop again straight away. Even that can’t stop us thinking about Grandad.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/sarah-lean/the-forever-whale/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Sarah Lean

A family secret waiting to be discovered… from bestselling author of A Dog Called Homeless.A shared story can last forever.Hannah’s grandad loves telling stories from his past, but there’s one that he can’t remember… one that Hannah knows is important.When a whale appears off the coast, clues to Grandad’s secret begin to surface. Hannah is determined to solve the mystery but, as she gets closer to the truth, Grandad’s story is more extraordinary than she imagined.Includes beautiful inside artwork from hugely talented illustrator, Gary Blythe.

Praise for Sarah Lean (#ub126c2e3-acec-50b3-a8c7-c7005abc29e1)

“Sarah Lean weaves magic and emotion into beautiful stories.”

Cathy Cassidy

“Touching, reflective and lyrical.” Culture supplement,

The Sunday Times

“… beautifully written and moving. A talent to watch.”

The Bookseller

“Sarah Lean’s graceful, miraculous writing will have you weeping one moment and rejoicing the next.”

Katherine Applegate, author of The One and Only Ivan

For Edward, who filmed our home and showed me his point of view … and the cat’s

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u674d538f-d523-591a-bb97-ff920fe6e2fd)

Praise for Sarah Lean

Dedication (#uc8365edd-63da-581d-b868-5b0f87e3e92d)

Chapter 1 (#u7383cd6e-4fac-58ef-9a6c-7a469d92cebe)

Chapter 2 (#u3bfed8d5-04d9-5147-83b4-7b5560e276a2)

Chapter 3 (#ufe5e7a8b-3ce2-52e5-bda3-369429b5882f)

Chapter 4 (#ude8ac76e-27c3-5c02-bf47-77188ef03b53)

Chapter 5 (#u84293276-6f16-562a-a1dc-24dad5a3c0e0)

Chapter 6 (#u42039b23-d271-5f16-a435-b97e323a190e)

Chapter 7 (#u5edcca30-ac86-5a6e-ba5c-a291e7b8c589)

Chapter 8 (#u8afc03a1-2a26-5ed7-bd99-2a3c5a288f95)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Books by Sarah Lean (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1.

GRANDAD DRAWS THE OARS INTO THE BOAT as we coast on the glassy water until we nudge into the bank. We both have our fingers over our lips, not to tell each other to be quiet, because we are, but because we think alike. I don’t know what Grandad has seen, I only know to trust him.

“Can you see it, Hannah?” Grandad whispers.

The dappled and striped shadows are barely moving in the golden September evening and I can’t see anything in the jumble of grasses and reeds. I shake my head.

“Keep looking,” Grandad whispers.

I follow his eyes, but it takes me a long while to spot the fawn, curled up and waiting. Its skin is hardly any different from the landscape around it. I can see the glisten of its black nose, but it knows to stay still, to be safe. Once I see it, it stands out a mile.

I whisper, “Is the fawn all right on its own, Grandad?”

He nods his head towards another curve of the bank. A deer is looking at us, anxious because she doesn’t want to draw attention to her fawn, who is separated from her by a channel of water.

Grandad smiles to himself. “Will you stay or will you swim across?” He says it as if he and the deer have a history together. We’ve seen deer here many times, but he’s never said that before.

“I didn’t know deer could swim,” I say, keeping my voice low and soft like his.

“That’s how they came to live on …” Grandad hesitates and looks over his shoulder. His eyebrows are crushed into a frown. He’s looking towards the island in the middle of the huge harbour, even though we can barely see it from here. But I’m not sure why.

“Furze Island?” I ask.

“Furze Island,” he repeats. “A long time ago a herd of deer swam over from the mainland and settled on the island.”

Grandad is still looking far away towards the harbour entrance, maybe for the billow of sails, to see if any broad and magnificent ships have blown in today.

We are quiet for a few minutes until Grandad speaks again. “It’s your turn to row now,” he says.

We change places in the boat. I see him stumble. He must be tired today. Grandad and I have taken a thousand journeys like this out in the quiet inlets of the harbour. Here we are just specks, tiny people marvelling at the changing sea and all the ordinary everyday things. These are my favourite days. I feel the familiar tug in my middle as the oars knock in their sockets and I row, pulling, rolling and lifting like Grandad taught me. The paddles splash like a slow-ticking clock.

“Hannah, I want you to remember something for me,” Grandad says. “Something important, in case I forget.”

I wonder why he would ever forget something important, but I want him to tell me.

“Anything for you,” I say.

“August the eighteenth,” he says. “You’ll remind me, won’t you?”

“That’s a long time away, nearly a year. Are you going somewhere?”

I only ask because I know that Grandad has spent all his life here in Hambourne, working with wood, rowing the inlets with me, and watching from his bedroom window for schooners and square-riggers in the harbour.

Grandad leans against the side of the boat and scratches his white beard and the bristles crackle under his fingernails. His eyes are warm and brown like oiled wood.

“Some journeys need us to travel great distances. But others are closer to home, like today when our eyes see more than what’s in front of us.”

“You mean like finding the fawn in the grass?” I see his face folding like worn origami paper into the peaceful shape I’ve always known.

Grandad slowly puts his gnarly old hand on the bench between us. My hand is still smooth like a map without journeys and I put it on top of his. We pile our hands over each other, his then mine, his then mine, like we always have. He pulls his huge hands out and gathers mine like an apple in his. And, just like always, that feeling is too big to keep inside me and bursts out and makes me laugh.

“Yes, great journeys like this,” he says. “Those great days that live in our memories and make us who we are.”

I’m not sure I exactly understand what he means. I just see something in him and I want to be like him too. Somewhere there in his sun-baked skin is a map of everything that made him who he is.

“Can I come with you on August the eighteenth, Grandad? I want to see what you’ve seen.”

Grandad’s ancient smile fills his cheeks and his eyes and I think of his face as a whole life-full of memories.

“It’s all right here.” His huge hand is over his chest. “The greatest power on earth. Remember, you have to think big, Hannah, and when things are good, think bigger.”

Grandad moved in with us after Grandma died ten years ago. I wasn’t exactly here then, still wriggling and growing into a baby inside my mum, but our home was his before it was mine. Grandad hadn’t liked to live alone and Mum hadn’t wanted him to live alone either. Grandma, who I never met, had done everything for him. She’d pressed his shirts and cooked his tea and put a cushion behind his head when he fell asleep in the chair. Even though he could have done all of these things for himself, she’d thought of him before she did anything.

I’m named after her. She was Hannah Jenkins, I’m Hannah Gray, and in lots of ways I’m like her.

Just then a voice calls across the water. Dad is waiting for us on the slope at Gorbreen slipway. It’s late, he’s saying; he’s telling us to come ashore.

I pull on one oar to steer us in.

Dad steadies Grandad as he climbs out and tells Grandad he should sit in the car, but he stays by the slipway and stares out to the harbour again. Dad and I roll the trailer under the boat. We pull it up the slipway and I leave Dad to hitch it to the car.

I stand beside Grandad and wonder why he’s not getting in the car.

“I think it’s time to put the boat away for the winter, Hannah,” he says.

I know this means we won’t go out rowing again until next spring.

A curlew is singing, and it’s soft and eerie, filling the bay and my ears.

“Grandad, tell me more about the deer,” I say.

Grandad nods and smiles, but he’s looking at the footprints of seabirds pressed in the soft muddy bank. They’ll be washed away when the tide comes in and draws out again.

“Come on, you two,” Dad calls. “Time to go.”

There’s a long moment before we go, when I see into Grandad’s warm eyes and he says, “I have quite a story I’m saving to tell you about the deer.” He says it quietly so only I hear his deep voice through the curlew’s song.

“Remember August the eighteenth,” he says again. “And one day, I hope you’ll go on the journey and see what I saw.”

2.

“READY FOR SOME TOAST, GRANDAD?”

Grandad likes his toast cooked under the gas grill so it’s dark brown with charcoal around the edge.

“I’ve got it,” I say because Grandad is staring blankly at the kitchen cupboards. I’ve already found the bread knife and cut an extra piece of bread as always.

“Watch the toast a minute,” I say and go outside to feed the birds.

Every morning I still try to do what Grandad and I have always done because it’s helping his memory stay alive. We haven’t been out in the boat again for nearly a year, but there are lots of other everyday things that we’ve always shared. Our early mornings are special, even though things are not exactly the same as they used to be.

Grandad has Alzheimer’s disease. One moment he is as he’s always been, wise and knowing and safe. Sometimes his memory fades like a ship disappearing into a sea mist.

Alzheimer’s usually picks on older people, but it’s not fussy about things like how big or bold a person is, or how important they are to their granddaughter. It’s taking all the things Grandad learned, all the things he saw and heard, all the things he loved. Alzheimer’s is a history thief, stealing his past and our future together.

The hedges shiver with excited twittering as I sprinkle the crusts on the lawn and as soon as I step back the sparrows get busy with the crumbs. I turn the earth with the garden fork that Grandad always leaves there. The robin comes and perches on the fork handle and watches the soil for the wriggle of a worm or centipede. Grandad once said that an ounce of brown and red feathers didn’t seem like much, but it’s the robin’s nature to be fierce like a tiger when it protects its territory. He likes the robin most of all.

I water our sunflowers. They’re taller than me, but the heads are still fresh and green. I can remember Grandad and I crouched in our wellies the first time we grew them. He’d shown me some small black and white striped seeds, shaped like miniature rowing boats.

“See this tiny little package?” he’d said, drawing away one of the seeds with his fingertip. “All it needs is water and the sun and in a few short months it will become a giant. And, when it’s a giant, it will have its own tiny seeds and each one can become a giant too.”

“Like it goes on forever?” I’d said.

“Just like that, only in a new plant.”

We’d pressed our seeds into pots of compost and I waited for them to grow. I hadn’t known what to expect and asked him every day when I came back from school where the giants were. Until I saw them for myself.

But even when the leaves turned dark and the stalks were thick with sap and towered over me, I still had to wait for the new seeds to ripen so that we could store them and then, the following spring, press them into the compost to grow once again.

Grandad follows me outside. I notice he doesn’t have his slippers on, but it doesn’t matter because the June summer ground is dry and warm.

I’ve asked Grandad the same question every day for years, even though I know the answer. I ask him again now: “When will the sunflower seeds be ready?” But this is the first morning he doesn’t reply. I say it for him: “When the hearts are golden,” so that one of us remembers.

Grandad nods towards the hard shadow of the fence in the far corner of our garden where a cat is twitching its tail. He struggles to remember the cat’s name.

“It’s Smokey,” I say, even though I’m sure Grandad will remember in a minute.

“Yes, that’s it,” he says. “We can try and keep the birds safe from him, but Smokey can’t help being a dog.”

I know Grandad meant to say cat not dog. Sometimes the Alzheimer’s makes him muddle things up, but I usually know what he means.

Smokey is a clever grey cat, and I’ve seen him catch baby sparrows before. Even though Mrs Simm gives him plenty of food, Smokey will take a bird if he wants to. I think of Smokey like he’s Alzheimer’s disease, creeping in and stealing things that don’t belong to him.

I hiss and Smokey scrabbles over the fence.

Grandad opens the garage door and he’s trying to untie the tarpaulin over his boat.

“Fair and fine today,” he smiles. “Shall we launch at Gorbreen?”

I don’t remind him we haven’t been in the boat since we put it away at the end of last September. I don’t tell him Dad won’t let us go out any more. “I’ll sort the boat out, Grandad. We could go and see the deer again.” And I lead him away, back into the garden.

“Grandad? Remember you were going to tell me a story?” I say. He doesn’t reply. An ocean of nothing washes into his eyes. “A story about the deer? About a journey?”

This isn’t the first time I’ve asked him. It isn’t the first time I’ve reminded him of the months passing. August 18th is now only eight weeks away.

“Journey?” he says. “Where are we going?”

Suddenly the smoke alarm shrills from the kitchen.

“Grandad, the toast!”

I run back inside. Smoke curls out of the grill and rolls up to the ceiling. I turn off the gas, climb on to the kitchen table and jump up to try to turn the alarm off before anyone else comes down for breakfast, but I’m not tall enough to reach.

Mum runs down the stairs. She stands on a chair and pokes at the alarm with a broom handle until it stops shrieking.

“Watch what Grandad’s doing, please,” Mum whispers as we try to wave the smoke away with tea towels.

“It was just an accident,” I say when Dad comes in.

Dad looks out at Grandad in the garden and I know what he’s thinking.

“It’s my fault,” I say. “I was feeding the birds and chasing Smokey away and watering the sunflowers and I forgot about the breakfast.”

“Sounds like you’ve had a busy morning,” Dad says.

He opens the fridge to get some juice and finds his car keys in there. He takes them out and bounces them up and down in his hand.

“Will you put those boxes by the front door into the car?” Mum says to Dad. “I’ll be along in a minute.” He and Mum share a long look before Mum says to him, “We’ll talk later.”

“Save some energy for school, Hannah,” Dad says on his way out.

Grandad comes into the kitchen. He opens the cupboard under the sink and pulls out a bag of birdseed. He doesn’t say anything about the smoke and the toast, he doesn’t close the cupboard door and the bag of seed is tipping from his hands.

“Grandad,” Mum says, “they’re spilling and going everywhere!” Dots of seed bounce up from the tiled floor around his feet. “Grandad?”

Grandad doesn’t seem to hear her and shuffles back outside, leaving a trail of seeds behind him. I hear the sparrows twittering, waiting for him.

“How is he this morning?” Mum says, sniffing at the bitter smell of burnt toast on her sleeve.

“He’s fine,” I say. “I heard him get up in the night so he’s probably just tired.” Mum frowns. “I can sweep that up,” I say, jumping down and reaching for the broom.

Mum holds on to the handle for a moment. “Hannah …” she says, but I don’t want her to say what everybody in our house has been saying recently, that they’re worried about the way Grandad is behaving.

“He’s fine,” I say again. “I forgot about the toast. It’s my fault.”

Mum sighs a little and says, “Go and help Grandad, love.”

“Mum!” I point to the toast on fire in the cooker behind her.

Mum steps down from the chair and uses the barbecue tongs to pick up the flaming toast and fling it out of the back door, and while she isn’t looking I close the door to the cupboard under the sink because I’ve noticed that there are things inside it that shouldn’t be there.

3.

“WHAT WAS THAT ALL ABOUT?” MY SISTER JODIE says, when Mum has gone to work. “And what’s that disgusting smell?”

I’m on the floor with a brush, but the seeds keep bouncing back out of the dustpan.

“I forgot to watch the toast,” I mutter.

Jodie pretends she doesn’t see me sweep some of the seeds under the doormat.

“Why don’t you just use the toaster like everyone else?” she says, painting gloss on her lips.

I bite my teeth together. “Why can’t Grandad have it how he likes it?”

Jodie doesn’t say anything. She’s more interested in smudging her lips and watching her reflection on the edge of the cooker.

“Why are you putting on lipgloss before you’ve had your breakfast?” I say.

She rolls her eyes and pours some cereal and milk and mutters to herself, “Where’s he put the sugar bowl now?”

Jodie sighs and goes out of the kitchen because the last time the bowl wasn’t by the kettle we eventually found it in a drawer in the sitting room. These things are Alzheimer’s fault, not Grandad’s.

I crawl across the floor and open the cupboard under the sink. It smells of damp. The sugar bowl is there, but it has tipped over the bags and bags of birdseed stuffed inside. I think about putting the bowl over by the kettle, but Jodie has come back and is watching me.

“What’s that in there?” she says.

I close the door, but Jodie comes over, so I push her away and sit with my back against the cupboard door with my arms folded and my legs crossed.

“Actually, this is my place for hiding private things,” I tell her, “so leave them alone.”

She stands with her legs either side of me and I make myself go all stiff, but it doesn’t work because she’s fifteen and five years bigger and stronger than me.

“Don’t be a baby,” Jodie says.

She holds my elbows, pulls me away and opens the door. She finds an old tube of sparkly lipstick, Grandad’s slippers and one of her books that went missing a few weeks ago. She leaves the cupboard door open and slides down to the floor, wiping sticky sugar crystals from her lipstick.

“I put those things in there when I was sweeping,” I say.

She holds the book in front of my face. The damp pages bulge.

“Sure you did.” Jodie twitches her mouth to the side. “I know what you’re trying to do, but it’s not like we don’t all know Grandad’s getting worse.”

I grit my teeth again and then take a minute because I want Jodie on my side. “I notice things more than anyone else. He’s tired today, that’s all. Can’t he just have a bad day like everyone else? He’ll be fine later, you’ll see.”

Jodie twiddles with her hair and we sit in silence with my words still echoing in my own ears because I know they’re not true. It’s what I want to believe though.

Jodie reaches inside the cupboard and finds four bars of chocolate.

“Grandad’s still hiding his chocolate, like a squirrel hides nuts for the winter,” she says. She doesn’t want to fight either. “Even before he got Alzheimer’s he’d forget where he put it.”

“Remember that time I ate so much of Grandad’s chocolate that I was sick?” I say.

We laugh quietly together.

I remember that night when Jodie and I had snuck around the house with a torch to look for Grandad’s hidden chocolate. We’d found loads and then hidden under the kitchen table. I ate far too much. Jodie knocked on Grandad’s bedroom door because we knew Mum and Dad would make a fuss, but Grandad would just put things right. He’d sent Jodie to bed and sat me on his lap in his high-backed chair with a bowl and a towel until I felt better.

“Did you know your grandma liked chocolate when she was a little girl?” he’d asked me as he wrapped us both in a blanket and took the bowl away from under my chin.

I shook my head through my tears. He smiled and his eyes crinkled.

“She had a sweet tooth like you, that’s why I’ve always had to hide my chocolate.”

“Did you marry her when she was a little girl?” I sniffed.

He chuckled quietly. “No, but even then I knew she was the girl for me.”

“How did you know?” I’d asked. He rubbed my back and I felt the sickness going and sleep on its way.

“How did I know? Well, that’s simple. Because something great put us together, bound us together forever, and it will never be undone.”

I remember tucking my head into his shoulder.

“What was the great thing?”

I remember feeling his wide chest heave as he took in a giant breath. I remember the dark and the quiet and the glimmer of light from the hall. I remember him saying, “Another time. Go to sleep now, little Hannah.”

4.

JODIE NUDGES ME. “HELLO? WHERE WERE YOU?”

I was thinking about the story Grandad had been meaning to tell me, wondering if it had anything to do with Grandma. I want him to remember because August 18th is getting closer, but no matter how many times I’ve said it, he doesn’t know why he asked me to remind him. None of us have birthdays on that day, no anniversaries, nothing like that, I checked. I think it must be to do with a memory Grandad has, something important that scoops him up and takes him back to another time so he can feel those things that happened all over again.

I think of how important it is for all of us, but especially for Grandad, to remember the bright things from the past. There must have been so many of them to make him so special, or maybe just one extraordinary thing. I hate that Alzheimer’s doesn’t always let him go back to times and places he loved the most, when I can, just like that, if I want to.

I’m still on the kitchen floor with Jodie.

“Do you remember Grandma?” I ask her.

“Not much.” Jodie looks disappointed with herself for a moment. “She had soft cheeks, that’s what I remember, and she always had toffees in her cardigan pocket. You could hear the papers rustling.” She pinches my cheek and pushes a chocolate bar into my hands. “You’re little and soft like Grandma was,” she smiles.

Grandad comes into the kitchen. “Time for breakfast,” he says.

“I’ll make you some more toast, Grandad,” I say.

I cut some more bread, put it in the toaster this time and turn the timer up high.

“My class is going on a field trip down to the quay today,” I tell him as we sit to eat our toast. “The mayor is unveiling a statue of a lifeboat. They’ve put a big cover over it so nobody can see it until today. Would you like to go down at the weekend and see it too?”

Slowly Grandad turns towards me. “We’ll hide my boat at Hambourne where nobody will find it.”

Right then I feel as if I’m on my own in the boat at sea, and I can’t see solid land on the horizon, and there’s nowhere safe to go. I’m about to tell Grandad that his boat is in the garage, but sometimes when I correct what he says he gets confused and I don’t want to upset him.

The dark edges of his toast crumble and fall into his lap. He doesn’t notice.

“Hannah,” Jodie says, breaking the uncomfortable silence, “we’d better get going.”

She picks up her bulging book and some photographs fall out from between the pages and scatter on the table. Three are of my grandma, Hannah Jenkins, who I never knew; three are of me, Hannah Gray. All of the photos are rippled and flaking from the dampness in the cupboard.

Grandad’s eyebrows furrow as we all look at the photos.

“Where’s Hannah?” he says. “I haven’t seen her this morning.”

Jodie stares at me, chewing the pad of her thumb. I try to hide what feels like a stone dropping in my stomach. She doesn’t say what I know she’s thinking, that neither of us knows whether he’s forgotten that Grandma died over ten years ago or if he’s now starting to forget me.

Jodie goes to the front door, but I can’t leave, not yet. I want to believe that when I come back this afternoon Grandad will be as he always was. I lean my hand on the table and kiss the white beard on his cheek.

“We’re going to school now,” I say.

His eyes brighten for a moment and he doesn’t know what he’s just said, but I see something unfamiliar in his face.

“Grandad, please remember the story you were going to tell me. About the deer, about a journey. It’ll be August the eighteenth soon.”

His eyes flicker as if he’s searching for something. He rubs his beard and I hear the bristles. I see brightness in his eyes, as if he’s found something.

“Hannah!” Jodie calls. “We’re going to be late!”

Grandad moves his hand and mine disappears underneath his.

“It’s quite a story, Hannah, about the greatest power on earth.”

I’m not sure if we can wait until August.

“Hannah, you have to come now!” Jodie shouts.

“Tell me about it after school, Grandad,” I say and kiss him again. “Today!”

“Today, after school, I’ll be waiting,” he says. “Let’s see if we can find that whale.”

“A whale?” I say, but Jodie has come back in and is dragging me away. “A whale, Grandad?” I call.

“Don’t forget,” I hear him say.

5.

THE MAYOR’S GOLD CHAIN LOOKS HEAVY, AND AT last he stops talking to the crowd and holds up a huge pair of scissors to cut the red ribbon around the statue. Four people are behind him, holding the corners of a big shiny black sheet so nobody can see what’s underneath.

Josh Beale makes a noise like he’s dying for some unknown reason, so our teacher tells him to shush, but he carries on gargling. I want to blank him out because I’m trying to think about what Grandad said this morning. I thought he wanted to tell me an important story about the deer, but he said we were going to find a whale. I don’t understand. I’m thinking about how Alzheimer’s disease is making me confused too.

A photographer from the local paper tells the mayor to wait a minute.

“Can we have some kids from the local school up there as well?” he says. “And a teacher.”

I am one of the children who get picked and we line up either side of the mayor and pretend we’re helping to hold the ribbon.

Everyone counts down, three, two, one. The scissors snip.

The four people let go of the cover and it billows above our heads, puffed up by the sea breeze. I feel the cool shadow over me as it ripples over our heads, falls and shrouds us. For a second the world goes dark and I smell something metallic. The people who were holding on to the cover drag it away again and everything seems just as it was. The crowd gasp then clap, but I have a funny feeling, like someone is standing behind me.

I turn round. The life-size statue is of a smooth golden-bronze figure, with no nose or eyes or mouth. It is leaning over the bow of a boat and reaching an arm to someone who is in the sea who doesn’t have a proper face either.

“Hey, you, little girl,” the photographer says, “look this way. Everyone smile.”

I can’t stop looking at the statue of the people with no faces. I see how hard the person in the boat is reaching for the one lost at sea.

I nudge Linus Drew who is standing next to me.

“Who is it?” I ask him.

“Who’s who?” he says.

“The statues. How are we supposed to know who they are if they don’t have faces?”

Linus shrugs, which is what he does a lot of the time. Our teacher hears me.

“They represent anyone,” Mrs Gooch says. “We’ll be talking about it later in class and reflecting on what we feel about the statue.”

I think of Grandad and how this morning he looked at me but didn’t see me. It feels like the shadow of the black cover is still over me.

“Anyone?” I say, catching Mrs Gooch’s arm. “How can a person be anyone? Surely they have to be someone?”

“Well, yes, that’s a good question, but this is art, Hannah, so there might be lots of possible meanings. Maybe we can find something of ourselves in it.” Mrs Gooch waits for me to say something. “Is everything all right?” she asks.

I nod. But it’s not true. Everything isn’t all right and I want to talk about it, but I’ve not told anyone that my grandad has Alzheimer’s. All my friends know him because of all the years he used to take me to and from school. He was the BFG at the school gates who lifted us up high in his arms and asked us to tell him what we’d been doing that day. I had told my friends Grandad didn’t come any more because we’d got too big and because I could walk to school on my own now.

Alzheimer’s isn’t like a broken leg or the flu; it’s buried in someone’s brain. You can’t see it. You just notice what’s missing. People don’t like it when it’s something to do with brains and not being normal.

We line up to go back to school and I’m partnered with my friend Megan. Mrs Gooch walks beside us.

“Megan?” Mrs Gooch says. “What did you think of the statue?”

“I thought it was nice because it’s to remember all the people who helped save lives at sea,” Megan says.

“Yes, it is. And how does it make you feel?”

I’m listening, but I don’t really want to join in now.

“I feel … like it’s good that we have people who will help us if we need them. And,” Megan continues, “it reminds me that I have to wear a life jacket when we go out in my uncle’s boat.”

“So it also reminds you of something to do with yourself. What about you, Hannah?” Mrs Gooch says. I look back at the statue, at the people who could be anyone.

“I don’t like that they don’t have names,” I say. “I want to know who they are.”

Is it just my name that Grandad is forgetting? Or is it much more than that? What about all our journeys in his boat, all our thousands of mornings, our talks, all the things that tie us together? Will he remember the story? Will he remember me when I get home?

6.

“GRANDAD?” I CALL AFTER SCHOOL, WHILE I FLICK on the kettle for him. I’m still thinking about the statue on the quay. Mrs Gooch said we could all try and find something of ourselves in the statue, but I’m thinking of Grandad instead.

The back door is open. At first I think I see ashes outside on the patio, and I remember the burnt toast from this morning. But they aren’t ashes. They’re tiny red and brown feathers.

My stomach turns to stone. I call Grandad’s name and run upstairs and look in all the rooms, but I’m already thinking that Smokey wouldn’t dare come so close to the house to take a bird if Grandad was here.

I come back to the kitchen. Grandad’s newspaper isn’t on the table.

Grandad doesn’t walk as well as he did, but most days he used to go as far as the shop down Southbrook Hill to get a bar of chocolate and a newspaper and some birdseed. On the way to the shop he’d stop to talk to Mr Howard who clips his box hedges with tiny shears into Christmas puddings and cones and clouds.

I run down the street. Mr Howard is clipping his hedge as usual.

“Have you seen my grandad today?” I call.

“Yes, he was headed thataway.” Mr Howard points with his sharp snippers towards Southbrook Hill. “I wished him a good afternoon, but he walked past without so much as a friendly word. I told him he looked a little peaky, but … well, that was nearly an hour ago.”

I am already running towards the hill.

Grandad isn’t at the shop. Suddenly my mind is racing, thinking of how he was when I left this morning. Had he heard me after all? Would he have gone to see the statue at the quay by himself? I take the road that leads down to the old town.

Papers rustle and tumble along the cobbled street, blown by the sea breeze coming through an alleyway between the shops. At the end of the alleyway I stop to catch my breath and look both ways. I hear boat masts clanking along the quay like alarms. In the distance I see Grandad shuffling unsteadily away from the new statue towards Hambourne slipway. I keep running.

Coming towards Grandad from the opposite direction I see Megan, Josh and Linus, who is on his scooter. As they pass Grandad, they speak to him. Megan watches over her shoulder, but Grandad doesn’t turn round so she stops and walks back to him. He looks down at the slipway, then out to sea.

“Grandad?” I call as I reach him. “What are you doing here?”

I hook my arm through his. He looks down at his other clenched hand. The ocean of nothing is in his eyes.

“Come on,” I say. “You’ve walked all the way to Hambourne slipway. Let’s go home now.”

I try to lead him away, but his arm is heavy. Megan, Josh and Linus stand uncomfortably nearby. “What’s wrong with him?” I hear Josh say to Linus.

“Grandad?” I say. “Let’s walk home together.”

“Do you want us to go?” Megan says.

But they don’t go and I can’t think what to do.

“Mr Jenkins,” Linus says. “Hannah and me will walk you home.”

Linus lays down his scooter and tries to take Grandad’s other arm.

“This way,” he says, but Grandad trembles.

“Grandad, please, it’s me, Hannah,” I say as a tear falls from his eye. “You’re safe.”

“Shall I get someone to help?” Megan says.

He’s fine, I want to say. But I see the unstoppable grey-green tide rushing away from the slipway steps, in the same way that Alzheimer’s is dragging Grandad away from me. Grandad doesn’t know who I am.

“Grandad, it’s me, Hannah. Remember, we’re going to go on a journey?”

I see a flicker in Grandad’s eyes. “The whale … it’s coming,” he says. He tries to speak again, but a sore groan comes from his lopsided mouth. He opens his hand.

Josh jumps back and falls over Linus’s scooter, tearing his knees on the pavement. Megan gasps and backs away. Only Linus stays beside me and stares at the robin, at the ounce of lifeless feathers in Grandad’s hands.

7.

“HOW LONG WILL GRANDAD BE IN HOSPITAL?” Jodie says that night.

It was a stroke that took a whole chunk more of Grandad away from us. The blood supply to his brain had been interrupted and more brain cells had died. It made the symptoms of Alzheimer’s worse, like he’d jumped down a whole staircase instead of taking the disease step by step.

Mum shakes her head. “We don’t know, love. He’s going to need some help to get him back on his feet again.”

“And then he’s coming home,” I say, “so that I can look after him.”

Mum and Dad glance sideways at each other.

“We’re not sure what the process is just yet,” Dad says. “Grandad is going to need a lot of therapy over the next few months—”

“Months?” I ask. He can’t be in hospital for months. I have to remind him of August 18th. I have to know what the story is so that we can go on our journey together.

“Weeks,” Mum says, “it might only be weeks.” Again she glances at Dad.

“Did Grandad say anything?” I ask. “Anything about me or anything at all?”

Mum shakes her head. “I don’t know if he knew it was me,” she says quietly. “I don’t think he recognised either of us.”

I push between Mum and Dad on the sofa, the only space I can see that feels safe.

“Can we visit him?” Jodie says, squeezing on the other side of Mum.

“Not just yet,” Dad says.

Mum touches Dad’s arm. “He’s very confused and weak at the moment,” she says. “I’ll go in tomorrow to check how he is and let you all know. Then we’ll see when he’s up to having more visitors.”

We know that nobody gets better from Alzheimer’s, but the doctor said it’s possible Grandad can recover from some of the symptoms of the stroke. But the way Mum described him sounded all wrong, like it was someone else in hospital, not my grandad. I keep thinking he’s still here, somewhere, only I can’t find him.

I get up from the sofa.

“I don’t want to see him in hospital,” I say. “But when he comes home, there’s something we have to do.”

“What’s that?” asks Dad.

They all look at me and I’m not sure now how to say what I’m thinking. Our journeys were about being together and discovering things, and seeing the world in front of us with bright eyes and open ears. I was going to take him out in the boat again. We wouldn’t go far – we’d stay in the inlets and quiet harbour waters. Because I’m sure, if we did, he’d remember everything he wanted to tell me.

“We’re going to take a journey together,” I say, but don’t wait for them to ask questions because I can’t explain anything more. How can I tell them that I think we’re going to find a whale?

I go out to the kitchen and rummage through the cupboards until I find the spray gun. I fill the bottle with cold water from the tap. I go out to the garden and shout into the night shadows, “Just you wait until Grandad gets back, Smokey! I know it was you that killed the robin.”

8.

“DID YOU THINK SOMETHING WAS WRONG WITH Grandad yesterday morning?” Jodie says when I meet her on the quay the next day on the way home from school.

I feel guilty because I’ve been trying to cover up some of the things he did, and maybe I shouldn’t have done that.

“Yes, but most of the time he was fine,” I say. It’s an effort to lie and makes my stomach hurt. “I wanted him to be fine,” I say quietly.

Jodie knows I feel bad and I can trust her not to make me feel worse.

We stare at the statue of the faceless people.

“It’s weird how they didn’t give them faces,” Jodie says.

“Mrs Gooch said it’s so we can all see something of ourselves in them.”