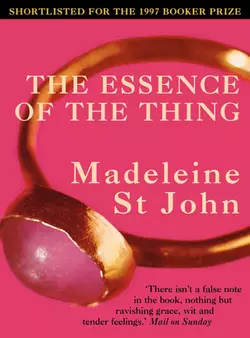

The Essence of the Thing

Madeleine John

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 152.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: An exciting new talent, shortlisted for the 1997 Booker Prize, hailed as ‘a triumph’ by The Times, and a poignant observer of human hearts, foibles and follies. ‘’There isn’t a false note in the book, nothing but ravishing grace, wit and tender feelings.’ Mail on SundayNicola’s problems began when she is finally told by her partner, Jonathan, ‘that we should part…’. She nips out to the off-licence to buy cigarettes and returns to find a stranger in her living room. The stranger looks like Jonathan, talks like Jonathan, yet Nicola did not recognise him as the man he was before. Jonathan had always been predictable, but now Nicola wondered where was the man she loved? How did he become such a mystery all of a sudden? Since when did a solicitor have hidden depths? Friends gather round, always ready to offer encouragement or insult her ex-husband, yet Nicola must face up to the adjustments of Life After Jonathan. It is not the experience of liberation, empowerment and excitement it is meant to be. Madeleine St John’s third novel is haunting and hilarious. St John is at her bittersweet best writing of the things women will do to hold on to love and the things men will do to escape it .