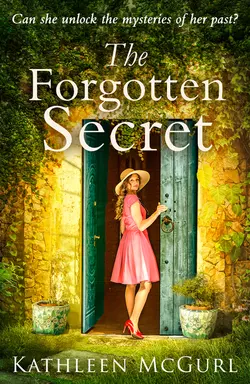

The Forgotten Secret: A heartbreaking and gripping historical novel for fans of Kate Morton

The Forgotten Secret: A heartbreaking and gripping historical novel for fans of Kate Morton

Kathleen McGurl

The brilliant new historical novel from the author of The Girl from Ballymor, Kathleen McGurl.Pre-order your copy now!

About the Author (#ud9152a44-4942-5a50-a667-fdb71a4c9a39)

KATHLEEN MCGURL lives near the sea in Bournemouth, UK, with her husband and elderly tabby cat. She has two sons who are now grown-up and have left home. She began her writing career creating short stories, and sold dozens to women’s magazines in the UK and Australia. Then she got side-tracked onto family history research – which led eventually to writing novels with genealogy themes. She has always been fascinated by the past, and the ways in which the past can influence the present, and enjoys exploring these links in her novels.

You can find out more at her website: http://kathleenmcgurl.com/ (https://kathleenmcgurl.com), or follow her on Twitter: @KathMcGurl (https://twitter.com/kathmcgurl?lang=en), Instagram: @KathleenMcGurl (https://www.instagram.com/kathleenmcgurl/) or Facebook (https://en-gb.facebook.com/KathleenMcGurl/).

Also by Kathleen McGurl (#ud9152a44-4942-5a50-a667-fdb71a4c9a39)

The Emerald Comb

The Pearl Locket

The Daughters of Red Hill Hall

The Girl from Ballymor

The Drowned Village

The Forgotten Secret

KATHLEEN MCGURL

HQ

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2019

Copyright © Kathleen McGurl 2019

Kathleen McGurl asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

E-book Edition © March 2019 ISBN: 9780008236991

Version: 2019-01-11

Table of Contents

Cover (#udeb7b2cc-9c33-58fb-ba1e-5ce488eb784f)

About the Author (#u2e23e6f8-7d41-50a6-8cae-9c7fb8723545)

Also by Kathleen McGurl (#u8174889d-0137-5b73-87a0-f814abe5f472)

Title Page (#uc9a250c3-8785-525c-bcb8-fd4d97249aa0)

Copyright (#ue28697a4-7198-5b1a-91a3-a20a9dfa46fe)

Dedication (#u9fdc8573-e646-564a-adc2-db6962c5e747)

Historical Note (#ud1fec3f3-a78f-5adb-8523-e9a11db588b2)

Chapter 1 (#uaba3967c-48d9-53ec-b271-9cd1a458c09b)

Chapter 2 (#u9c19c91c-a924-525c-8bed-d6e97a7fcfb9)

Chapter 3 (#ubdebeda8-cbdc-5d33-8bae-9b5ae1fe5c21)

Chapter 4 (#u46bc39ff-f602-52f7-a26e-a1eeed54bcb3)

Chapter 5 (#ud0c5d86d-ad79-598a-9a80-7dcb2f2ec79c)

Chapter 6 (#ueb8398dd-cefa-57ef-8a34-d4b0ed3e5a04)

Chapter 7 (#u267c4b1a-a60f-5406-b80f-0ed74a28a2a4)

Chapter 8 (#u55401e55-4565-537f-b1a8-c0e363ad473a)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

Dear Reader (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

To all my Irish in-laws

– this one’s for you

Historical Note (#ud9152a44-4942-5a50-a667-fdb71a4c9a39)

If you were educated in Ireland you’ll probably know all this already, in which case feel free to skip this section. Everyone else – please read on. I hope this will help provide some context for the novel. I’ll keep it as short as possible!

By the early twentieth century, Ireland had been ruled by England since Norman times. Over the years there had been various uprisings: notably Wolfe Tone’s United Irishmen rebellion of 1798. In response to this, the British Parliament passed the Acts of Union in 1800, formalising Ireland’s status as part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

Many Irish were still unhappy under British rule. Harsh penal laws against Catholics and the aftermath of the Great Famine of the 1840s led to ever greater hostility against English landlords. In the late 1800s and early 1900s there was much discussion in parliament about the possibility of ‘Home Rule’ for Ireland. By 1914 a Government of Ireland bill was making its way through the British parliament system when the First World War broke out. It was put on hold.

But Irish nationalists weren’t prepared to wait for the end of the war for discussion to resume. At Easter 1916 various Irish nationalist forces combined in an uprising, taking control of parts of Dublin. The Proclamation of the Republic was read out from the steps of the General Post Office, declaring Ireland’s independence. British troops soon quashed the uprising, and most of its leaders were executed.

In the parliamentary elections of 1918 just after the end of the war, Ireland’s primary nationalist party Sinn Fein won a large majority of the Irish seats in parliament. However, they refused to swear the required oath of allegiance to the King, and instead set up the first Dáil Éireann (Irish Council), declaring Ireland to be an independent nation. Thus, Ireland slid into war against Britain. (One Sinn Fein MP was Constance Markievicz, the first woman to be elected to the UK Parliament. She was in jail at the time, for her part in the 1916 uprising. Constance was also the founder of the Fianna Éireann, ‘Warriors of Ireland’, a kind of military boy scouts, whose alumni went on to join the Republican army.)

In the cities, British troops kept control but in provincial areas it was the paramilitary police force – the Royal Irish Constabulary – that was left fighting against the nationalist Irish Volunteers. The RIC was reinforced by the undisciplined Black and Tans, named for their mismatched ex-army and police uniforms.

The War of Independence was largely a guerrilla war, with atrocities committed by both sides. It was characterised by attacks and counter-attacks, shootings and reprisal actions, often against civilians. Towns were looted, homes and businesses were burned, and people executed.

In 1921 the British prime minister offered a truce: the terms of which divided Ireland, forming the Irish Free State but with six counties of Ulster remaining part of the United Kingdom. The Irish leadership were split over whether to agree, but eventually signed the treaty. This disagreement led inevitably to civil war, between those who were pro- and anti-treaty, that lasted from 1922 until a ceasefire in spring 1923.

During World War II Ireland remained neutral, and it was after ‘the Emergency’ (as it was termed in Ireland) that the Republic of Ireland was formally inaugurated in 1948.

The anti-treaty nationalist forces combined as the Irish Republican Army, and remained active on and off throughout the decades, fighting for Ireland to be once more united. Their campaigns escalated during the 1970s and 80s, a period known as ‘the Troubles’, and only came to an end with the signing of the Good Friday Agreement of 1998.

In this novel, the historical chapters start in 1919, just as the War of Independence was escalating in intensity. I’ve referred to Irish nationalist forces during the War of Independence as ‘Volunteers’ throughout, though there were various groups involved. Volunteers from this period are often known now as the ‘old IRA’. Blackstown is a fictional place.

Chapter 1 (#ulink_70d9f763-28f6-5c40-8a50-335a34b6a572)

Clare, February 2016

We rounded a corner, turned off the narrow country lane and onto a gravel track, drove past a little copse of birch trees and there it was. Clonamurty Farm, County Meath, Ireland. Old, tired, dilapidated and in urgent need of repair. But it was mine. All mine, and only mine, or soon would be. A little shudder of excitement ran through me, and I turned my face away so that Paul, my husband, would not see the smile that had crept onto my face.

I think it was in that moment that I first realised my life could change, for the better. If only I was brave enough to seize the day.

‘What a godforsaken mess of a place. Good job this is a hire car. That track’ll be trashing the tyres,’ Paul grumbled, as he parked the car beside a rusty old piece of farm machinery that had waist-high thistles growing up through it.

‘I expect it could be renovated, with a bit of money and a lot of effort,’ I said. Already I could see its potential. With the weeds cleared, the stonework repointed, the rotten windowsills replaced and painted, and a new porch built around the front door it would be beautiful. A lazy Labrador sunning himself in the yard and a couple of cats nonchalantly strolling around owning the place would complete the picture.

As if I’d conjured them up, two tabbies appeared around the corner, mewing loudly, tails held high, coming to see who we were and whether we had any food for them, I suspected. I smiled to see them, and bent down, hand outstretched, to make their acquaintance.

‘Clare, for God’s sake don’t touch them. They’ll be ridden with fleas and Lord knows what else.’

‘Aw, they’re fine. Aren’t you, my pretties? Who’s been looking after you then, since your daddy died?’ I felt a pang of worry for these poor, beautiful creatures. Though they weren’t especially thin, and their coats seemed in good condition.

‘Their daddy. Oh grow up, will you?’ Paul stomped away from me, towards the front door, and fished in his pocket for the key we’d picked up from the solicitor in nearby Blackstown. Actually the solicitor, Mr Greve, had handed the key to me. It was my uncle Pádraig who’d left me the farm in his will, after all. But Paul had reached out and snatched the key before I’d had the chance to take it. The farm wasn’t quite mine yet. I needed to wait for probate to be completed, but we’d had the chance to come over to Ireland for a weekend to view the property and make a decision about what to do with it.

I followed Paul across the weed-infested gravel to the peeling, blue-painted front door, and watched as he wrestled with the lock. ‘Damn key doesn’t fit. That idiot solicitor’s given us the wrong one.’

I peered through a filthy window beside the front door. ‘Paul, there are boxes and stuff leaning against this door. I reckon Uncle Pádraig didn’t use it. Maybe that key’s for another door, round the back, perhaps?’

‘The solicitor would have told us if it was,’ Paul said, continuing to try to force the key into the lock. I left him to it and walked around the side of the house to the back of the building. There was a door at the side, which looked well used. A pair of wellington boots, filled with rain water, stood beside the step. I called Paul, and he came around the house, his lips pinched thin. He never liked to be proved wrong.

The key fitted this door and we entered the house. It smelled musty and unaired. It had been last decorated at some point in the 1970s, I’d say. I tried to bring to mind my memories of the house, from visits to Uncle Pádraig and Aunt Lily when I was a child, but it was a long time ago and I’d been very young then. My maternal grandmother – Granny Irish as I called her – lived here too in those days. I have clear memories of one of my cousins: David (or Daithí as he renamed himself after he became a committed Republican), hazy memories of his two older brothers but only vague impressions of a large rambling house. I have better memories of the barn where I used to love playing hide-and-seek with David among the bales of straw. Sadly, David and his brothers had all died young, which was why the farmhouse had been passed down to me.

The door led into a corridor, with a grubby kitchen off to the right and a boot-room to the left. Straight ahead a wedged-open door led to the main hallway, which in turn led to the blocked-off front door, the sitting room and dining room. This area looked familiar. There’d been a grandfather clock – I looked around and yes, it was still there! – standing in the hallway. A memory surfaced of listening to it chiming the hour when I was supposed to be asleep upstairs. I’d count the chimes, willing it to chime thirteen like the clock in my favourite book – Tom’s Midnight Garden – and was always disappointed when it stopped at twelve.

We peered into each room. Upstairs there were four bedrooms, a box-room and a bathroom. All felt a little damp, as though it had been months since they’d been aired or heated. As with the downstairs rooms, the decor was horribly dated. I expected Paul to make sneering comments about the state of the place – and to be fair, it was in a total mess – but he surprised me by commenting favourably on the layout, the size of the rooms, the amount of light that flooded through the large front windows. ‘It could be quite a house, this,’ he said.

‘It certainly could,’ I replied. ‘And we could come for holidays, let the boys use it and perhaps rent it as a holiday home in between, after we’ve done it up.’ I could see it now. Long, lazy weeks, using this house as a base to explore this part of Ireland. It was within easy reach of Dublin and the east coast, and the surrounding countryside of rolling farmland was peacefully attractive.

‘Don’t be ridiculous. We can’t do this place up. We live in London. And why on earth would anyone want to come here for a holiday? There’s nothing to do. No. Like I said earlier, we’ll sell it to some developer or other, and I have plans for what to do with the money.’

‘Can we at least discuss it?’ I couldn’t believe he was dismissing the idea of keeping the farm, just like that.

‘What’s to discuss? I’ve made up my mind. As soon as probate comes through, I’ll put it on the market. We can find suitable estate agents to handle it for us while we’re here.’ He smiled at me – a smile that did not reach his eyes but which told me the matter was closed. ‘Come on. Let’s go and find somewhere we can have a cup of tea. I’ve got to get out of this depressing house.’ Paul turned and walked along the passage towards the back door. Somewhere upstairs a door banged, as though the farmhouse was voicing its own disapproval of his words.

As I followed Paul out, knowing there was no point arguing with him when he was in this kind of mood, I realised that he would not be able to do anything without my say-so. The house and all its outbuildings, Uncle Pádraig’s entire estate, had been left to me. Not to Paul, just to me. So if I wanted, I could refuse to sell it, and there’d be nothing Paul could do about it. Except to moan and snipe and make my life a misery, of course.

It hadn’t always been like this. We’d been married twenty-five years. He swept me off my feet when I first met him. I was fresh out of university with a degree in textile design but not enough talent to make it as a designer, and was working in a shoe shop by day and a pub by night to make ends meet. It was not what I’d dreamed of for myself.

Then one day, the best-looking man I’d ever set eyes on came into the pub and ordered himself a gin and tonic, and ‘whatever you’re having, love’. Usually I turned down these offers – the bar staff were not allowed to drink alcohol while on shift although we were allowed to accept soft drinks from customers. But this time, something about his sparkly eyes that seemed to look deep into the heart of me, something about his melodious voice and cultivated manner, something about his sharp suit and immaculate shirt made me accept, and then spend the rest of the evening between customers (it was a quiet night) leaning on the bar chatting to him.

He was in the area for a work conference, staying in a hotel just up the road, but couldn’t stand the company of his colleagues another moment so had escaped from the hotel bar and into the nearest pub. By the end of the evening we’d swapped phone numbers and agreed to meet up the following day when I wasn’t working, for a drink. He turned up that second night with a gift of the best box of chocolates I’d ever had, and a perfect single stem red rose in a plastic tube. My previous boyfriends had all been impoverished arts students. No one had ever treated me like that before.

He used to sing that Human League song to me – you know the one: ‘Don’t You Want Me, Baby’. I wasn’t exactly working as a waitress in a cocktail bar when he met me, but pretty close. And he liked to tell people he’d pulled me up, out of the gutter. ‘Who knows where she’d have ended up without me, eh?’ he’d say, patting my arm while I grimaced and tried not to wonder the same thing.

Paul had been kind in those early days. Thoughtful, considerate, and nothing was too much trouble for him. He was always planning extravagant little treats for me – a surprise picnic on the banks of the Thames, a hamper complete with bright white linen napkins all packed and ready in his car; tickets to Wimbledon centre court on the ladies’ final day; a night away in the Manoir aux Quat’Saisons. All would be sprung on me as a surprise.

It was exciting, but looking back, perhaps slightly unnerving in the way that it left me with no control over my life. I’d have to cancel any plans I had made myself, to go along with his surprises. And any twinge of resentment I felt would turn quickly into guilt – how could I resent him doing such lovely things for me? When I told my friends of his latest surprise treat, they’d all sigh and tell me how lucky I was, and ask could I clone him for them.

Gradually I’d stopped making my own plans, at least not without checking with Paul that it’d be all right for me to see my parents, or spend a day shopping with a girlfriend, in case he had something up his sleeve for us. And so as Paul and I became closer, my old friends had drifted away as I’d rarely seemed to have time to see them and had cancelled on them too many times.

We left the farm in silence, and got back in the car to return to Blackstown in search of a café. I spent the journey wondering what plans Paul had made for the money if we sold the farm. Perhaps he’d surprise me, the way he so often used to, and present me with round-the-world cruise tickets, or keys to a luxury holiday home in Tuscany.

It was the sort of thing he might have done in the early days of our relationship. He’d stopped the surprises after the boys were born – it wasn’t so easy to swan off on weekends away with toddlers in tow. But the boys were in their twenties now and had left home – Matt had a job and Jon was a student. Perhaps Paul did want to rekindle the spirit of our early relationship. I resolved to try to keep an open mind about the farm, but I would certainly want to know his plans before I agreed to sell it.

There’s something funny about being at my stage of life. OK, spare the jokes about the big change, but being 49 and having the big five-oh looming on the horizon does make you re-evaluate who you are, what your life is like, and whether you’ve achieved your life’s dreams or not. Ever since my last birthday I’d been doing a lot of navel-gazing. What had I done with my life? I’d brought up two wonderful sons. That had to count as my greatest achievement.

I say ‘I’ had brought them up although of course it was both of us. Paul wasn’t as hands-on as I was – it was always me who took them to Scouts, attended school sports day, sat with them overnight when they were ill. But then, Paul would always say his role was to be the breadwinner, mine was to be the mother and homemaker.

I’ve tried to list more achievements beyond being the mother of well-adjusted, fabulous young men, but frankly I can’t think of any. We have a beautiful house – that’s down to me. Maybe that can count? I decorated it from top to bottom, made all the curtains, renovated beautiful old furniture for it. I did several years of upholstery evening classes and have reupholstered chairs, sofas and a chaise longue. But all this doesn’t feel like something that could go on my gravestone, does it? Here lies Clare Farrell, mourned by husband, sons and several overstuffed armchairs.

We arrived in Blackstown, and Paul reversed the car into a parking space outside a cosy-looking tea shop. I shook myself out of my thoughts. They were only making me bitter. Who knew, perhaps he did have plans for the proceeds of the sale of the farm that would help rekindle our relationship. Surely a marriage of over twenty-five years was worth fighting for? I should give him a chance.

‘Well? Does this place look OK to you?’ he asked, as he unclipped his seatbelt.

I smiled back as we entered the café. ‘Perfect. I fancy tea and a cake. That chocolate fudge cake looks to die for.’ Huge slices, thick and gooey, just how I liked it. I was salivating already.

‘Not watching your figure then? You used to be so slim,’ Paul replied. He approached the counter and ordered two teas and one slice of carrot cake – his favourite, but something I can’t stand. ‘No, love, that’s all,’ he said, when the waitress asked if he wanted anything else. ‘The wife’s on a diet.’

I opened my mouth to protest but Paul gave me a warning look. I realised if I said anything he’d grab me by the arm and drag me back to the car, where we’d have a row followed by stony silence for the rest of the day. And I wouldn’t get my cup of tea. Easier, as on so many other occasions, to stay quiet, accept the tea and put up with the lack of cake.

It was so often like this. Once more I wondered whether I’d ever have the courage to leave him. But was this kind of treatment grounds enough for a separation? It sounded so trivial, didn’t it – I’m leaving him because he won’t let me eat cake and I’ve had enough of it. Well, today wasn’t the day I’d be leaving him, that was for certain, so I smiled sweetly, sat at a table by the window, meekly drank my cup of tea and watched Paul eat his carrot cake with a fork, commenting occasionally on how good it was.

Chapter 2 (#ulink_d63b914b-026b-579b-be1b-88d853550226)

Ellen, July 1919

Three good things had happened that day, Ellen O’Brien thought, as she walked home to the cottage she shared with her father. Firstly, she’d found a sixpence on the road leading out of Blackstown. Sixpence was the perfect amount of money to find. A penny wouldn’t buy much, and a shilling or more she’d feel obliged to hand in somewhere, or give it to Da to buy food. But a sixpence she felt she could keep. It hadn’t lasted long though, as she’d called in at O’Flanaghan’s sweetshop and bought a bag of barley-drops. She’d always had a sweet tooth and even though she was now a grown woman of eighteen she still could not resist the velvety feel of melting sugar in her mouth.

The second good thing was the one that most people would say was the most important of the three. She’d got herself a job, as upstairs maid for Mrs Emily Carlton, in the big house. Da had been nagging her to get a job and bring in some money to help. There was only the two of them now in the cottage since one by one her brothers had gone across the seas to America, Canada and England. Da was getting old and appeared less able (or less willing, as Ellen sometimes thought, uncharitably) to work, and had said he needed Ellen to start earning. She’d been keeping house for him for five years now, since Mammy had died during that long, cold winter when the whole of Europe had been at war.

But it was the third good thing to happen that Ellen rated as the best and most exciting; the event she’d been looking forward to for months. It was the news that at long last Jimmy Gallagher was home from school. For good, this time. He was the same age as her, just two months older, and had been away at a boarding school for years, coming home only for the long summer holidays.

It was Mrs O’Flanaghan at the sweetshop who’d told her the news. The old woman remembered how Ellen and Jimmy would call in for a pennyworth of sweets on a Friday after school, back in those long-ago childhood days when they both attended the National School and had been best friends. Jimmy had passed his exams now, and finished high school. ‘Set to become a lawyer, if he goes off to university and studies some more, so he is,’ said Mrs O’Flanaghan. ‘But first he’ll help his daddy with the harvest. And maybe he’ll decide to stay on and become a farmer. Those Gallaghers have such high hopes for him, but I’m after thinking he’s a simple soul at heart, and will be content to stay here in Blackstown now.’

Ellen certainly hoped so. She calculated when would be the soonest that she could go over to Clonamurty Farm to see Jimmy. Not today – it was already late for her to be getting home to cook the tea. Tomorrow, then. Sunday, after church, if she didn’t see him in church. She was not due to start at Mrs Carlton’s until Monday.

Ellen rounded the corner and turned off the lane, up the rutted track that led to her home. It was looking more and more dilapidated, she thought, sadly. Back when Mammy was alive, Da would never have let the thatch get into such a state, sagging in the middle and letting water in over the kitchen. The gate was hanging off its hinges, and the front door was waterlogged and swollen, its paint long since peeled away.

‘Hello, boy,’ Ellen said to Digger, the elderly wolfhound who had hauled himself to his feet, wagging his tail at her approach. She fondled his ears. ‘Daddy in, is he? I’ve news for him, so I have.’

Digger pushed his muzzle into her hand, and she remembered the pack of barley sugars. She gave him one, which he ate with a crunch, and then she pushed open the door to the cottage.

‘Da? I’m back.’ Mr O’Brien was sitting in his worn-out armchair beside the kitchen range, his head lolling back, mouth open, snoring loudly.

‘I’ll make you a cup of tea, will I?’ Ellen didn’t wait for an answer, but began setting the kettle to boil, clattering around a little so as to wake him naturally.

It worked. ‘Eh, what?’ he said, sitting upright and blinking to focus on her. ‘Ah, tis you, Mary-Ellen. Late, aren’t you?’

‘Not really. I have good news, Da. I’m after getting myself a job, up at Carlton House. I’m to start on Monday. Ten shillings a week.’

‘Ah, that’s grand, lass. Keep two yourself and the rest towards the housekeeping. You’ll be back each day to cook for me?’

Ellen shook her head. ‘The job’s live-in, Da. I’ll get a day off every Sunday and will come home then.’

Her father pursed his lips. ‘Who’ll cook for me, then?’

Ellen was silent for a moment. ‘I’ll make you pies on Sunday that’ll last the week.’

‘And what of potatoes? I’ll have to cook my own, will I?’

‘Da, you wanted me to find a job. And now I have. You’ll be grand.’

Seamus O’Brien grunted. ‘Cooking me own tea. Women’s work, that is.’

Ellen ignored him. She was used to his grumps, and knew he was more than capable of boiling a few potatoes. She poured water into the teapot. Should she tell Da about Jimmy being home? A smile played about her lips as she thought of Jimmy, and imagined meeting up with him tomorrow.

‘What’s that you’re so pleased about, girl? Your new job?’

‘Aye, that, and the fact that Jimmy Gallagher’s home, so I heard.’ The words slipped out unbidden.

‘Michael Gallagher’s lad, from Clonamurty?’

‘That’s him, Da. I was at the National with him, remember?’

Seamus O’Brien shook his head. ‘Don’t be getting ideas. Them Gallaghers are too good for the likes of us. They’ll be looking for a lass with money for their Jimmy. Not a kitchen maid, like you.’

‘Upstairs maid,’ Ellen said quietly. But her father’s words stung. Was she really too lowly for Jimmy? Not that she thought of him as a potential suitor, or at least, she tried not to. These last few years they’d only seen each other a half-dozen times each summer and Christmas, when he’d come home for school holidays. She’d thought their friendship was strong, and that Jimmy liked her company as much as she liked his, but what now? Now they were both grown, both adults, would he still like her? Or was she just a childhood friend, someone to think back on fondly?

She didn’t know. She wouldn’t know until she saw him again and had the chance to judge his reaction on seeing her. She hoped if nothing else they would still be friends, still share a few easy-going, laughter-filled days together like they always had. One day, she supposed, he would find himself a sweetheart and that would be hard for Ellen to deal with, but she would smile and wish him well. Occasionally she had dared fantasise that she would become his sweetheart, but her father was probably right. His parents would want someone better for him, and who could blame them?

He’d almost certainly be at Mass tomorrow. She’d find out then, for better or for worse, whether his last year at school had changed him or not.

Jimmy was indeed at Mass. She saw him walk in with his parents and younger brother, so tall now, so handsome! His dark-blond hair, too long across his forehead so that he had to keep flicking it back. A smattering of freckles across his nose – faded now compared to what he’d had as a child. His broad chest and long, elegant hands. She felt a flutter in her stomach. Would he want to know her any more? She tried to catch his eye, carefully, as she didn’t want her father to see her doing it. But he didn’t notice her, or if he did, he made no sign.

The service, led by Father O’Riordan, was interminably long. The priest was getting on in years, and Ellen often thought he was simply going through the motions rather than truly finding joy in the presence of God. His sermon, as it did so often, rambled on, touching on several topics but not fully exploring any. Ten seconds after it was over Ellen could not have said what it was about. The only thing for certain was that she had learned nothing from it, despite listening intently.

When she went up to receive the Holy Sacrament, she once more tried to catch Jimmy’s eye, but he was at the far end of a pew on the other side of church, and did not go up for communion. That was odd. To be in church and not receive communion? He must have something on his mind he wished to confess to the priest, and had not had the chance to do so before Mass, she thought.

At last the service was over. She walked out with her father, feeling a strange mixture of delight at having seen Jimmy again but disappointment that he had not acknowledged her in any way. At the door of the church her father stopped to say a few words to the priest, and she caught sight of Jimmy once more, over the priest’s shoulder, standing a little way off.

He was looking right at her, smiling slightly, and making a surreptitious hand signal, fingers splayed then closed, not raising his hand at all. Anyone watching would have thought he was just stretching his finger joints.

But Ellen knew different, and the sight of that gesture filled her with joy. It was part of their old childhood sign language – a set of signs they’d made up so they could signal to each other in class without the teacher realising. There were signs for ‘see you after school by the old oak’, ‘watch out, the teacher’s coming’, ‘I have sweets, want to share them?’ Jimmy had made the sign for ‘see you after school’. She was puzzled for a moment but quickly realised he must mean ‘after church’. She signalled back ‘yes’ (a waggling thumb) and had to suppress a snort of laughter when he replied with the sign for ‘want to share my sweets?’ accompanied by a lopsided cheeky grin.

As soon as her father had finished speaking to the priest, she made some excuse about having left something in the church. ‘I’ll see you back at home, Da,’ she said. ‘Couple of things I need to do, then I’ll be back to cook the Sunday dinner.’

‘Aye, well, don’t be long, girl,’ he replied, his mouth downturned as it so often was these days. He walked off, not looking back, and as soon as he’d turned the corner and was out of sight Ellen darted off through the churchyard in the opposite direction, to the old oak that stood on the edge of a field beside the river. It was near the National School, and had been the place where she and Jimmy always met up after school when they were children.

He was there now, waiting for her. ‘Well! Here we are, then,’ he said, smiling broadly. She was not sure whether to hug him, kiss his cheek, or shake his hand. In the past she’d have thrown herself at him, arms round his neck, legs around his waist if her skirts were loose enough and she was sure he could take her weight. But they were grown-up now, and surely that wasn’t seemly behaviour? She was still dithering when he resolved the issue for her – holding out his arms and taking her two hands in his. ‘Well,’ he said again, ‘you’re all grown-up now, Mary-Ellen, so you are!’

‘Still just Ellen, to you, though,’ she replied. There were altogether too many Marys around the place without adding to them by using her full name.

‘The lovely Ellen,’ Jimmy said, bringing a blush to her cheek. ‘You’ve changed.’

‘How?’

‘More beautiful than ever,’ he said, so quietly she wondered if perhaps she hadn’t heard him properly. When she didn’t reply, he let go of her hands, took her arm and began walking through the park. ‘Aren’t you going to ask me how my last year in school was?’

‘How was it?’

‘Boring as all hell.’

Ellen gasped to hear him use such a word, and Jimmy laughed. ‘The teachers taught me nothing. Nothing at all. But I studied enough to pass my exams, so the old man’s pleased with me. Now I’ve the whole summer at home to help with the harvest and decide whether I want to go on to university and become a lawyer, or stay here and become a farmer. Wildly different choices, aren’t they?’

Ellen nodded, willing him to say he wanted to stay in Blackstown. ‘What will you do?’

‘Ah, my sweet Ellen. Sometimes fate has a way of deciding things for us. Sometimes something becomes so important to a person that they actually have no choice. They just have to follow where their heart leads them, no matter what.’ He gazed at her as he said these last words. For a moment she thought he was going to pull her into his arms and kiss her, right there, in the middle of the park, where other folk were strolling and might see, and might recognise them and tell her father! But she’d take that risk. Her heart surged. Surely he was saying that she was the most important thing in his life, the thing his heart would insist he follow?

But his next words changed everything. ‘Ellen, let me tell you what happened this year at school. The teachers taught me nothing but I learned plenty, anyway. One of the old boys organised a club, called the Dunnersby Debaters. But we weren’t a debating society. We were there to learn Irish history, the real history, not the English version the masters taught. We learned the Irish language. We heard all about Wolfe Tone, and the 1798 rebellion, and all the other attempts to rise up against our oppressors. We learned exactly what happened in the 1916 Easter uprising, and why we must not let those efforts die in vain. Ireland must have home rule. One way or another, we must find a way to achieve it. I joined the Fianna Éireann too, and learned to shoot, so when the time comes I’ll be ready.’

His eyes were blazing as he made this speech. She could see the passion surging through him like wildfire. They’d spoken before, a year or two ago, about the prospect of Irish independence, but had mostly been repeating what they’d heard their parents say. Ellen had never been sure whether it would be good for Ireland or not – would the country not be worse off if it threw off its connections to its powerful, wealthy neighbour and branched out on its own? Was it not better to be a little part of a bigger nation, than a small, poor nation that was independent?

But clearly Jimmy had made up his mind the other way. What would that mean for him? What would it mean for her, and the future she hardly dared dream about, a future with Jimmy at her side?

Chapter 3 (#ulink_d4093ca8-f46b-5ce3-85e5-c6df15bd7bb0)

Clare, February 2016

‘So, how was the house, Mum?’ my son Matt asked, when I met up with him for our regular weekly coffee a few days after coming back from Ireland. Matt had graduated from university a couple of years ago, and now worked for an IT consultancy based in London, which meant we could easily meet up.

I sipped my Americano before answering, trying to decide how best to describe Clonamurty Farm. ‘Hmm. Dilapidated,’ was the word I picked in the end.

‘But with potential?’ Matt was studying me carefully. ‘Mum, there’s a twinkle in your eye. You can’t disguise it.’

I smiled. He probably knew me better than anyone, Paul included. ‘Yes, it certainly has potential.’

‘So?’

‘So what?’

‘So are you going to move there, do it up, get in touch with your Irish heritage and all that?’

‘Your dad doesn’t want to. He wants to sell it to a developer as soon as possible.’

Matt frowned. ‘It’s not his to sell though, is it? What do you want to do with it?’

I picked up a teaspoon and stirred my coffee, which didn’t need stirring, before answering. When I looked up Matt was still frowning slightly. I wanted to tell him to stop before the lines became permanent. I wanted to rub my thumb between his eyes to smooth them out. ‘Well. How do I answer that?’ I said, still playing for time.

‘Truthfully? Come on, Mum. You can tell me anything – you know that. I won’t tell Dad.’

‘OK. The truth is, I don’t really know what I want. Part of me says yes, your dad is right, we should sell it, take the money, invest it for the future, give some to you and Jon.’

‘And the other part?’

I took a deep breath. ‘Says I should move to Ireland, no matter what.’

‘With or without Dad?’

‘It’d probably be … without him, I think. He wouldn’t want to look for a new job in Ireland. Perhaps he’d come over at weekends, or …’

‘… or you’d use this as a chance to leave him?’

There they were. The words. Out there, in the wild. Matt had said it, not me, but I needed to answer. It felt like the point of no return. I took yet another deep breath, this one shuddering. ‘Ye-es. I suppose so.’

I don’t know what reaction I expected from him. But it wasn’t this. He leapt up, grinning, came round the table and leaned over me to hug me. ‘Oh, Mum. At last! You’re doing the right thing. You know you are. It’s time for you to have a life of your own, not dictated by Dad. He’s always putting you down and trying to stop you doing anything for yourself. I know you stayed together for me and Jon, which is lovely of you, but we’re grown-up now and if you two separate, we won’t mind at all. It won’t hurt us. Jon feels the same – I know because we’ve discussed it.’

I picked up a napkin and dabbed at my eyes, which had sprung a leak. It was a weird feeling, knowing our two sons had discussed their parents’ relationship and come to the conclusion I should leave my husband. Very weird. ‘We’ve been married twenty-five years, Matt. It’s a lot to throw away and I need to think it through carefully before doing anything.’

‘You’re not throwing anything away. You’re just moving on to a new phase in your life. It’s the perfect opportunity, Mum. You’ll have somewhere to live and money of your own, so you won’t be dependent on him or any divorce settlement. You’ll be far enough from Dad to stop him interfering. Because you know he’ll try to.’

I nodded. Yes, he would try to interfere. He’d try to stop me. ‘But I’d also be far from you and Jon.’

‘Ryanair fly to Dublin for about fifty quid return. We could come over to see you for weekends every couple of months. I’d love to see my great-grandparents’ farm.’ Matt sat down again opposite me, but kept hold of my hand across the table. I loved that my sons were so tactile and affectionate.

I felt a tear form in the corner of my eye. ‘Can’t help but wonder what your grandparents would have thought, if they’d still been here. Marriage is supposed to be for life.’

Matt smiled. ‘They’d feel the same way Jon and I do, I’m sure. They’d want what’s best for you, and it’s been obvious for ages that staying with Dad isn’t doing you any good. You know, Grandma used to pull me to one side and ask me on the quiet if I thought you were happy with Dad. I used to say yes of course you were, as I didn’t want to worry her, not when she was so ill at the end.’

‘Oh, sweetheart.’ I had to wipe away another tear at that. Mum had been in such pain in her final days as the cancer ate away at her. She’d been in a hospice, in a private room, with Dad at her bedside and the boys and me visiting as often as we could. I went every day at the end. Paul only came once, stayed five minutes then announced he had too much to do. I’d told myself it wasn’t his mum, and he was feeling uncomfortable not being part of her direct family. But the truth was he had never really wanted much to do with my parents. Dad had died only a year after Mum. But before he’d gone, he’d gifted me his car – a three-year-old Ford Mondeo that Paul had immediately appropriated as his own, trading in our elderly BMW. Until Uncle Pádraig’s legacy, the car was the only thing I owned outright, under my own name.

‘So, you going to do it, Mum?’ Matt said, dragging me back into the present.

‘I don’t know yet. I’m going to have a good long think about it.’

‘You do that.’ He was thoughtful for a moment, then looked at me with a smile. ‘Do you remember that poem Grandma used to quote? I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree. That’s what you should do.’

‘Go to Innisfree?’ I said.

‘Or whatever the farm in Ireland is called. Arise and go now. That’s my point.’ He pulled out his wallet to pay for our coffees. ‘This one’s on me. And don’t forget you can ring me any time if you want to discuss it more. Jon and I will do all we can to help you.’

‘Not if it puts your dad against you. I don’t want you to ruin your relationship with him on account of me.’

‘Mum, I don’t have much of a relationship with him anyway. Don’t think Jon does either. It was always you, when we were kids. You were the one who walked us to school, took us to swimming lessons, helped us with homework, played endless games of Monopoly with us on rainy days and all the rest of it. A proper parent. Dad was just a shadowy figure in the background.’

‘On holidays though, he played with you then?’

‘Did he? I don’t remember. When I think of family holidays, I picture you digging sandcastles or helping us fly kites. I suppose Dad was there, but he just doesn’t figure in my memories.’

Matt got up to pay our bill. Those last words had made me kind of sad and lost in my reminiscences again. I’d always thought that our family holidays were the best times, when Paul had been a proper dad for once.

We hadn’t been married long when I became pregnant with Matt. Paul was delighted when I showed him the blue line on the pregnancy test, and immediately took me out to a swanky restaurant for dinner. Bit wasted on me though, as I had developed an odd metallic taste in my mouth (which continued for the whole first trimester) and nothing tasted right. But I was happy that he was happy, and excited about the prospect of motherhood.

Paul insisted I gave up working in the shoe shop when I was six months gone. ‘You can’t be bending down over people’s feet with that huge bump,’ he’d reasoned.

‘But what about maternity pay?’ I’d said. ‘I need to work a bit longer to qualify.’

‘You won’t be going back to work after the baby’s born, Clare,’ he’d said. ‘You wouldn’t want someone else bringing up our child, would you? Anyway, a decent nanny would cost us more than you earn anyway.’

There’d been no arguing with him, and while I was sad to give up having my own little bit of income, he was right about the cost of childcare. I could always find something part-time later on, when our child or children reached school age.

It was an easy pregnancy. I spent the last three months getting a nursery ready for the baby, decorating the room in palest yellow with a stencilled frieze of farm animals around the walls, painting an old chest of drawers and adding more animals to it, making curtains and a matching floor cushion, and re-covering a fireside chair that would be my seat for night-time feeds. That was the first chair I re-covered, and I enjoyed it so much I vowed to learn how to do upholstery properly.

When Matt was born, Paul showered me with gifts. Flowers, chocolates, champagne, pretty white shawls to wrap the baby in, a gorgeous bracelet with a baby charm. No expense spared. I felt like a queen. I felt loved and cherished.

Paul proved to be a hands-off dad. I don’t think he changed a single nappy. I told myself he worked hard all day and deserved a break in the evenings and at weekends, and baby-minding was my job, but to tell the truth, I would have appreciated a bit of help now and again, and maybe a few lie-ins. It would have helped Paul bond with Matt.

I tried to encourage him to do more. But he’d just sigh and say some things were best left to women. I told myself that once we were out of the baby stage, he’d be more interested. When he could take Matt to the park, kick a football, ride bikes – that’s when Paul would come into his own as a father.

Little Jon came along when Matt was nearly three, and here, I thought, was the opportunity for Paul to do more with Matt, leaving me free to look after Jon. Matt was potty trained and a very biddable child, easy to handle. But there was no change. Paul kept a distance from both boys. He’d occasionally accompany us on a trip to the park or the swimming pool, to the boys’ delight. Family holidays were fun too, when Paul would act like a real dad for once, being relaxed and playful, the way I remember my own dad being all the time. I always put it down to Paul’s stressful job in telecom sales, and assumed he could only properly relax when he was away from it all on holiday. At least that’s how I remembered it, but Matt seemed to have different recollections.

It was probably the holidays and the way the boys worshipped him when he did spend time with them, that kept me with Paul all those years. Looking back, I’d probably fallen out of love with him by the time Jon was a year old. I just told myself everyone found the baby and toddler years hard. And he still bought me surprise gifts and treats every now and again. I knew he must love me. I was just being ungrateful and somehow dissatisfied with life. I had a husband who from the outside appeared to dote on me, two gorgeous little boys, a lovely house. What more did I want?

Now, as I left the café with Matt, I realised that after so many years I was at last beginning to work out what I wanted. A little bit of independence and the freedom to make my own decisions, such as whether I wanted cake with my cuppa or not.

I had a phone call that night from Jon. He rang at eight p.m. – the time when Paul goes out to his regular twice-a-week gym class. Whenever the boys ring at this time it’s because they know they can talk to me without their dad listening in.

‘Hey, Mum. I had a call from Matt. He told me what you and he were talking about today. Just wanted to let you know that if you decide to go for it, and leave Dad, that’s all right by me. Actually, more than all right. I think it’d be great for you.’

‘Aw, Jon.’ I felt tears well up again. Maybe it was the menopause coming on, or maybe just the stresses of making such a big decision, but I seemed to be constantly weepy.

‘Hope you don’t mind that he told me,’ Jon said, sounding a little unsure.

‘Of course not. I know you two are close and tell each other everything.’

‘Ahem, not quite everything. He doesn’t know about my dangerous liaison with the fire-eating circus acrobat who tied my legs in knots during a three-day tantric sex session …’

‘Jon!’

‘Joking! Course he knows about that!’

You never knew with Jon, when he was being serious and when not. But he never failed to lighten the mood and make me smile. My tears were gone already.

It took a few weeks more, and a lot of soul-searching, and some long chats with Matt and Jon, before I finally came to a decision. Yes, I would do it. I would leave Paul. I would arise and go now. Perhaps I should have done it years ago, but it would be easier now – less messy as I could simply move to Ireland and leave him the UK house. I just needed to wait for probate to be completed so that the inheritance was mine, and then I could go. Oh, and I needed to tell Paul, of course. How, I wasn’t sure. I decided to wait for the right moment. Whenever that would be.

Uncle Pádraig’s solicitor, Mr Greve, called me one day, while Paul was at work and I was in the middle of going through my wardrobe, throwing out clothes I knew I’d never wear again and wouldn’t want in Ireland. I was in the habit of doing this once a year anyway, so it wouldn’t rouse Paul’s suspicions.

‘Mrs Farrell? I have good news for you. Probate is almost complete. I need your bank account details to pay the money into.’

‘Money? I thought there was just the farm in Ireland.’

‘Ah no. There’s a fair amount of money in the estate as well. Not a huge fortune mind, but enough. So I need your bank name, account number and sort code. Do you have them to hand?’

I felt a wave of panic wash over me. The only bank account I had access to was a joint account. If the money was paid into that, Paul would be able to get at it. He’d notice it immediately – he got alerts on his phone whenever there was any activity on his account – and he’d quite possibly move it out and invest it somewhere else where I couldn’t touch it. He might be my husband of twenty-five years, but I couldn’t trust him with this. It was my money.

‘Er, no. Sorry, I don’t have them right here. Can I call you back later with them?’

‘Yes of course, but the sooner the better so we can get this all neatly tied up. You have my number, I think.’

‘I do, yes.’

‘Good. I’ll wait to hear.’ Mr Greve hung up. He’d sounded vaguely irritated that I wasn’t the sort of organised woman who had bank details to hand.

I grabbed a jacket and my handbag, and rushed out of the house. Paul had the car at work, but it was only a forty-minute walk into the town centre and if I hurried I could get there, see to my business and get home again in time to cook Paul’s tea. Yes, I was the type of housewife who always had her husband’s dinner on the table when he came home from work. A throwback to the 1950s. Sometimes I despised myself for it. Though not for much longer.

There were three banks with branches in our small town, and I nipped into the first one I came across – Nationwide.

‘I need to open a bank account,’ I told the clerk, slightly breathless from my fast walk to town.

‘All right, what kind of account did you want? And do you already have any accounts with us?’ she asked.

‘Just a regular account. And no, I don’t.’

‘OK. Wait there, I’ll see if someone’s available to talk you through the options.’

I was lucky. Someone was available and I was ushered to a desk behind a partition, where a smart young man with ‘Dan’ on his name badge sat opposite me with a pile of leaflets. I was blushing with embarrassment that a woman of my age – almost 50 – did not have her own bank account, and did not know the difference between a SIPP and an ISA, a current account and a savings account. I’d had my own account before Paul, of course, but I’d closed it on his advice when I stopped working when Matt came along, and had just used our joint account for the twenty-four years since then. Dan was patient and gentle with me, but I could tell he thought I was an oddity.

‘Well, Mrs Farrell, as you’re wanting to pay in an inheritance but still have instant access to the money, I would recommend our Flexclusive Saver account. Decent interest rates yet fully flexible. We can open that now for you, if you have some proof of ID and proof of address.’

I hadn’t for a moment thought I’d need anything like that. I’d been so far removed from all this sort of thing – Paul of course handled all our finances and paid all the bills. But thankfully I had my driving licence on me, and at the bottom of my handbag was a water bill with a shopping list scribbled on the back. Dan accepted those.

Twenty minutes later I left, grinning like a cat with cream, clutching a piece of paper with my bank account numbers on it. A card would arrive by post in a couple of days, Dan said. Our post arrived around midday so I’d be able to pick it up before Paul saw it.

Back home I called Mr Greve, passed on the bank details, and made myself some tea in an attempt to calm myself down a little. I’d done it. I’d taken the first step towards independence.

Next step, tell Paul.

Chapter 4 (#ulink_ddf07be4-b4a5-52d8-a779-df64568bab2e)

Ellen, July 1919

Ellen set off to start work at her new job the next day with a spring in her step. She’d packed a few things in a holdall – even though Mrs Carlton’s big house was only a couple of miles away from her father’s cottage, her job was live-in as she had to be up at six to set the fires in the bedrooms, bring hot water upstairs in ewers and then fetch the mistress’s breakfast, which she always took in her room.

She was looking forward to starting the job, a new life away from her increasingly morose father. She felt a pang of guilt that he’d have to fend for himself during the week, but she’d baked two large mutton pies the previous day and stored them in the pantry, and she’d made enough soda bread for a few days, and a fruit cake, and stocked up on general groceries. He’d manage, she told herself.

And Jimmy was home. Jimmy was home! When they’d parted the day before, he’d promised to meet her this morning to walk with her as far as the gates to Carlton House. She had to pass his home, Clonamurty Farm, on her way anyway.

Sure enough, there he was, leaning against the gate post as she approached. The low morning sun was behind him, shining like a halo around his floppy blond hair. Such a contrast to her own dark curls. Ellen smiled as he greeted her and began walking alongside her.

‘So, all ready for your new job?’ he asked.

‘Yes, all ready. I’ve my things packed in this bag. They’ll give me a maid’s uniform up at the house. My room will be right up in the attic. I hope there’s a window with a view.’

‘Maybe a view back to Clonamurty, and if you’re unhappy you can signal me from the window. One lit candle means all’s well, two means come and rescue me.’ There was a mischievous glint in Jimmy’s eyes as he said this.

Ellen giggled, but a little part of her wondered whether Jimmy would really ‘rescue’ her if she was in need. It was an enticing thought. She felt herself blushing so turned her face away.

They chatted and bantered as they walked the short distance to Carlton House. Jimmy did not say anything more about his political beliefs or his desire for an independent Ireland, for which Ellen was grateful. Their time together would be all too limited now that she was working six days a week, plus cooking for her father on the seventh, and she did not want to spend time talking politics.

At the end of the long drive lined with elegant poplar trees that led up to the big house, Jimmy stopped. ‘You probably oughtn’t to be seen walking with me on your first day, so I’ll leave you here. Good luck!’

‘Will I see you on Sunday?’ Ellen asked, turning to face him. ‘It’s my day off. I’ll be at Mass, of course, and have to see Da, but …’

‘I’ll meet you here and walk you home. Then I can see you after church if you’ve time, and walk you back here in the evening. If you like.’

Her eyes shone. ‘Yes. Yes, all that would be lovely, so it would.’ Something to look forward to, all week. Six days until she’d see him again.

‘I’ll be away, then. Hope all goes well. They’ll love you, sure they will.’

He took a step towards her and for a moment she thought he was going to take her in his arms and kiss her goodbye, but he just picked a loose hair off her shoulder and then raised his hand to wave farewell.

She watched him walk back the way they’d come for a moment, then turned and began making her way up the long gravel driveway towards the big house. She’d only been there once before – the previous week when she’d attended an interview with Mrs Carlton. She’d expected to meet a housekeeper, but it was the lady of the house herself who conducted the interview. There’d been an odd question about Ellen’s family background, and she’d found herself talking about her great-grandfather who’d fought alongside Wolfe Tone in the old rebellion. Mrs Carlton had pronounced herself pleased, and asked Ellen to begin work.

And now it was time to start her new life. When she’d reached the house, she went around to the kitchen door, knocked, and was shown in by a scowling housemaid.

‘You’ll be the new maid, then,’ the girl said. It was a statement not a question. ‘I was after wanting that job upstairs. Easier than downstairs. Don’t know why the mistress didn’t give it to me.’

Maybe because you’re so grumpy, Ellen thought, but she smiled sweetly and held out her hand. ‘I’m sorry if I got the job you wanted. I hope it won’t stop us being friends. My name’s Mary-Ellen, but everyone calls me Ellen.’

‘I’m Siobhan,’ the other girl said, ‘and you’ll be sharing my bedroom.’ She did not shake Ellen’s hand.

Siobhan took her through the kitchen and along a corridor to an office, where Mrs Carlton was sitting doing the household accounts.

‘Ah, Ellen. Thank you, Siobhan. You may return to your duties. I’ll show Ellen where her bedroom is and what her tasks are to be.’

Siobhan bobbed a curtsey and left the room, but not before she’d thrown another scowl in Ellen’s direction. Ellen suppressed a sigh. She’d hoped she’d make friends here at the Hall, not enemies. And she’d be sharing a room with Siobhan. She resolved to work harder at being friendly towards the other girl. Siobhan was probably just jealous, but it wasn’t Ellen’s fault she’d got the job.

‘I really should employ a housekeeper,’ Mrs Carlton said, as she led Ellen upstairs, along a corridor and up a second flight to the attic rooms. ‘I suppose I just enjoy retaining control of the household too much. Anyway, here’s your room. That’s Siobhan’s bed, so you have this one under the window.’ She opened the door onto a small room, with a dormer window that looked out across gently rolling farmland. In the distance was a ribbon of silver – the Boyne. Ellen crossed to the window and peered out. Yes, she could just about make out a farmhouse not far from the river. Clonamurty Farm, and in it, Jimmy.

‘This is perfect, thank you, ma’am,’ she said, placing her holdall on the bed. ‘Should I change now or get straight to work?’

‘Ah, your uniform. Just a moment, I’ll call Siobhan to fetch it. Oh, and call me Madame. Not ma’am, and not Mrs. Those forms of address are just too … English, I suppose.’ She smiled. ‘Just my little idiosyncrasy.’ And then she left the room.

Ellen took the opportunity while she was alone to have a look around. Besides the two narrow beds there was a washstand, basin and ewer, a chest with four drawers, two bentwood chairs and a small mirror hanging on the wall. There was a neat little fireplace with a bucket of sweet-smelling turf to burn beside it.

A worn-out hearthrug was on the floor, and a sampler hung over the fireplace with the words ‘Many suffer so that some day all Irish people may know justice and peace –Wolfe Tone’ embroidered upon it, signed with the initials E.C. Mrs Carlton’s first name was Emily, Ellen knew. Was it Mrs, sorry, Madame Carlton herself who’d embroidered the sampler? The words were so patriotic, so Irish, and yet Madame Carlton was English – at least, she was one of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy. She was a widow, but her husband had been a Member of Parliament, spending most of his time in London.

Ellen had always thought the desire for Irish independence was something only the poor wanted and fought for: the downtrodden, those whose ancestors had perished during the Great Famine, those who had nothing to lose and everything to gain. But here was the widow of a British MP, embroidering quotes like that and hanging them in her servants’ rooms, and asking not to be called Mrs because it was too English-sounding.

She was still standing in front of the fireplace pondering this when Madame Carlton arrived back in the room, carrying a neat black dress, white apron and cap. ‘Your uniform, Ellen. I have guessed at the size, but it should be about right.’ Her gaze followed Ellen’s to the sampler. ‘And are you a patriot, my dear?’

Ellen gaped for a moment, not sure how to answer or what she was expected to say. Madame watched her for a moment and then her eyes softened. ‘I am sorry. That was wrong of me to ask such a thing on your first day, when I barely know you. Suffice to say that all here are Fenians and true Irish patriots. I would employ none other. We believe in the Cause. Irish independence must be won at all costs. I know something of your family, Ellen, and feel that you will fit in perfectly.’

She handed Ellen the uniform. ‘So, put this on, and report downstairs to me. You’ll find me in the housekeeper’s office.’

Madame Carlton left the room, closing the door behind her, to allow Ellen to get changed. She did so, quickly, her mind reviewing all that she had heard. Between Jimmy’s declaration of support for the Cause and now her employer’s, she seemed to be surrounded by people who wanted a free and independent Ireland. But her own thoughts on the matter were still unresolved.

The week passed quickly. Although she was an upstairs maid, with easier work than the downstairs and scullery maids had, she found it exhausting and crawled into bed each night aching all over. She was on her feet from six a.m., running up and down stairs, setting the fires, fetching fuel, jugs of warm water to wash, bringing breakfast trays up and clearing them away after. Later she had to make the beds, change sheets, clean bedrooms, sweep the stairs and landings, clear out grates and set the fires ready for the evening.

Besides Madame Carlton there was a succession of visitors using the many guest rooms on the first floor. Ellen rarely glimpsed the guests, and was often instructed to leave their breakfast trays outside the door. Madame seemed endlessly busy, running her household, entertaining her guests and conducting serious-looking meetings either in the library or the dining room. When these were in progress, the servants were instructed to keep well out of sight at all times. Madame herself would emerge to fetch a tray of refreshments if needed.

Siobhan had softened towards her a little, as Ellen had displayed relentless friendliness towards the other girl. She’d got the impression Siobhan was most miffed about having to share a bedroom, so Ellen had tried to be as easy-going a room-mate as possible. They’d begun chatting for a few minutes at bedtime, exchanging little stories about their work, speculating on who Madame’s latest visitors had been.

‘Something to do with the fight for independence,’ Siobhan said one night. ‘Our Madame’s really tied up in all that, you know. She’ll suck us into it as well, if we’re not careful, so.’

‘Do you want to be part of the fight?’ Ellen asked.

Siobhan was quiet, as though she was mulling over her answer. ‘Not sure. What about you?’

‘I’m not sure either,’ Ellen had whispered in reply. Even as she said the words, she wondered how she’d have answered if it had been Jimmy asking her. She knew she’d do anything for him.

At last it was Saturday evening, and Ellen was free to leave Carlton House for twenty-four hours. She’d arranged to meet Jimmy at the end of the drive, and had time to go for a walk with him before returning to her father.

She walked down the drive carrying half a ham wrapped in muslin that the cook had given her. ‘The mistress said to give it to the dogs but it’s still perfectly good, so you take it home for your daddy, now,’ the cook had said, handing it to Ellen with a smile. She had so much to tell Jimmy. Not least her growing realisation that Madame Carlton seemed to be deeply involved with the fight for independence.

Jimmy was leaning against the gate post, hands in pockets and a thoughtful expression on his face.

‘All right, Jimmy?’ Ellen said as she approached, and Jimmy hauled himself upright with a shrug.

‘Yes, sure I am. How’re you? How was your first week?’

They fell into step, walking down the lane towards Clonamurty Farm. Ellen told him of her duties, of her room-mate Siobhan and her less-than-friendly welcome, of the other staff.

‘And your mistress, Mrs Carlton? How do you get on with her?’ Jimmy asked. There was an odd tone to his voice.

‘She seems very nice,’ Ellen said, guardedly. She still wasn’t sure whether she should voice her suspicions about Mrs Carlton. Even to Jimmy.

‘Just nice?’

‘There’s something odd. She wants to be called Madame and not Mrs. I think she’s … well, I think she’s involved with the Irish Volunteers, so I do.’ There. It was out in the open. ‘Jimmy, you won’t say it to anyone, will you? I’d hate for her to get in any trouble because of me.’

To her surprise Jimmy laughed, and then flung an arm about her shoulders. ‘Ah, my sweet Ellen. Of course she is involved! She runs a branch of the Cumann na mBan. You’ve heard of that, haven’t you?’

She had. It was the Irishwomen’s Council – an auxiliary branch of the Irish Volunteers, fighting for Irish independence. ‘So you know what she does? There are always people coming and going, having meetings and all sorts.’

‘Yes, there would be. She’s quite senior in the organisation. She’s important to the Cause.’ Jimmy nodded knowledgeably.

Ellen wanted to ask how he knew so much about it, but Jimmy had withdrawn into himself again, with that serious, thoughtful expression he’d had when they met. She wanted to snatch away his hat, run off with it, have him chase her, laughing, the way they used to when they were children. But something told her it wouldn’t work now; he’d just be annoyed at her. They were adults now, and Jimmy clearly had something serious on his mind.

‘What are you thinking about?’ she asked, quietly, after they’d walked in silence for a few minutes. They weren’t far now from his parents’ farm, and he might leave her there, and they’d have no more chance to talk until after Mass tomorrow.

He smiled at her, and stopped walking. There was a wooden fence lining the road, and he pulled her over to sit with him on the top rail.

‘I’m thinking about my future. And Ireland’s future. And how the two are intertwined.’

She frowned. ‘Of course they are, since you live in Ireland.’

He shook his head. ‘I mean in a more profound way than that. I’ve made my decision, Ellen, about what I’m going to do now that I’ve left school. I’ve been thinking long and hard about it this week, and I realise now what’s the most important thing to me.’

She watched him, a little spark of hope in her heart that he would tell her the most important thing in his life was her, and that he had decided he wanted to be with her, now and always. But as soon as the thoughts crossed her mind, she dismissed them. Something in his expression, in his distant gaze across the fields, told her he cared more for something else. ‘What is it?’ she whispered, hardly wanting to hear the answer. It would change everything – she knew it.

‘Ireland, Ellen. Ireland’s future, Ireland’s freedom. Ireland’s independence. That’s it, Ellen. That’s the most important thing, the thing my heart says I must follow, no matter what. I’ve joined up. I’m a Volunteer. The Cause, Ireland’s independence, that’s what’s calling to me. I’ll be neither a lawyer nor a farmer. I’ll be a soldier for Ireland, till the day I die or the day Ireland is free, whichever comes first.’

He jumped down from the fence as he made this speech, and wheeled around to face her. She’d never heard so much passion in his voice. Tears sprung to her eyes as she realised two things simultaneously – first that she loved him with all her heart and would never love anyone else as much, and second that she was losing him.

‘Ah, Ellen, what has you crying?’ His expression was softer now, the fire in his eyes dimmer but still there, smouldering.

‘The thought of you fighting and maybe dying for the Cause. Surely it’s not worth it?’ She dashed the tears away with the back of her hand.

‘It is worth it. One man’s life is a small sacrifice to make for a country’s future. I love my country, Ellen. I have to do this. I have to fight the British. You are not to worry. I’ll be all right. I’ll do my part, but I’m young and fit, canny and clever, and I’ll not get caught and I’ll not be killed. You wait and see! You’ll be proud of me yet, and we’ll be able to tell our grandchildren that I fought for their future.’

Ellen was once again left speechless, still trying to process what she’d heard about grandchildren, when Jimmy grabbed her suddenly, pulling her off her perch on the fence. He squeezed her against him and landed a huge, passionate kiss on her lips. It wasn’t quite how she’d imagined their first kiss would be – she’d pictured a more tender moment – but it was still a kiss and it was intense.

‘Ah, Ellen,’ Jimmy said, holding her tightly and burying his face in her hair. ‘It has me all fired up. And you, my love – believe me, you mean just as much to me as Ireland does.’ He kissed her again, gently this time, his lips warm against hers, the fire within him spreading into her and with it the certain knowledge that he loved her. And she loved him, and together they would build a future.

If the Cause didn’t claim Jimmy first.

Chapter 5 (#ulink_2a9b071c-9b13-54af-8df8-87ee71c44f2e)

Clare, April 2016

In the end I waited till probate was complete, the money was in my account and Clonamurty Farm was in my name. I didn’t mean to wait that long to tell Paul; I was just weak and couldn’t seem to find the right moment. Or the courage.

He’d had his dinner – fish pie, and a glass of Sauvignon Blanc. I’d eaten almost none of mine, having made up my mind that tonight was the night we’d have the conversation. My stomach was churning. ‘Not eating?’ he’d asked, and I’d grunted and shrugged, then forced down a mouthful or two.

I’d cleared up. He’d gone to the sitting room and put the TV on in the background while he read a magazine. Something to do with cars, I noted. Well he’d need to read up on car recommendations. ‘Our’ car was actually my car – Dad had given it to me when he gave up driving, and I was going to use it to take my stuff to Ireland.

I stood in the doorway of the sitting room, breathing deeply and summoning up the courage to speak. Paul looked up and frowned. ‘Well, either come in or go out. Don’t stand there like some kind of zombie.’

‘Sorry. I’m coming in. Just – we need to talk.’ I took a few steps forward. I could feel my heart pounding.

‘Hmm? What about?’ Paul had returned his attention to his magazine.

I took a deep breath. ‘Probate on Uncle Pádraig’s will is complete. The money’s in my bank account.’

‘Ah, right. That’s good. I’ll get online and invest it later. Got my eye on a couple of safe retail bonds.’

‘Er, no. I mean it’s in my bank account. My private one, not our joint one.’

He put down his magazine and looked at me over the top of his reading glasses. ‘You don’t have a bank account.’

‘I do now.’ Oh why could I not just come out and say it? Paul, I’m leaving you.

‘Why is the money in there? I can’t access it if it’s only in your name.’

That’s the point, I wanted to say, but stopped myself. ‘Paul, the money’s in there because it’s mine, not yours. And the farm is mine.’

‘But we decided to sell it, didn’t we? What are you getting at, Clare?’

This was it. This was the moment. ‘I’ve decided to keep the farm. I want to live there.’

‘What? But it’s uninhabitable!’

‘Just a bit dirty. I’ll soon sort it out.’

‘Clare, you are mad. It’s revolting. It’ll take more than a bit of Vim and a quick hoover round, you know. Not something you can do in a few weekend visits.’

‘I’ll have longer than that. I’m going to live there permanently.’

‘Well I’m bloody not!’ He stood up and crossed the room, towering over me.

‘No. I’m not expecting you to. Paul, I think … I want … I think we should separate.’ There. Said it. The words were out there and there was no clawing them back. To give myself strength I imagined Matt and Jon standing at my side, holding my hands and lending me support. And Mum, behind me, whispering in my ear, arise and go now.

‘Separate? What? Why? Don’t be ridiculous. Aren’t you happy? You have this beautiful house, all the time in the world to get your hair done or whatever it is you do with your days. Get this stupid notion about the farm out of your head, Clare. I don’t want to hear any more of it. We’ll get it on the market as soon as possible, and use some of the money to go on a cruise. How does that sound?’

‘I don’t want to go on a cruise. I want to live at the farm in Ireland. On my own. I’m sorry, Paul, but this is it. No, I’m not happy. I need things to change.’

‘You’re menopausal, aren’t you? That’s what this is about. Your hormones. Can’t you see a doctor and get some tablets or something?’

That did it. ‘I’m not fucking menopausal, Paul. You’re not listening to me. I’m saying I want to leave you. I have had enough of you controlling everything and telling me what to do. I want to be independent, to be in control of my own life, and now I have the money to do it. I’ll be gone in a few days’ time, and till then I’ll sleep in Matt’s old room.’

‘Is this about Angie?’

I stared at Paul. Angie was a woman he’d worked with for a while. He’d invited her round for dinner once or twice, and she’d brought a different date each time. He’d slept with her at a conference, I’d found out. He’d apologised and swore it’d never happen again. And I’d believed him and stayed with him. For the sake of the boys, who’d been under 10 at the time.

‘Angie?’

‘Because if it is, remember that all happened ages ago. Been over for years and there’s been no one else since.’

‘No, it’s not about Angie,’ I said, coldly. ‘As you say, that’s all in the past.’ To tell the truth, I’d pretty much forgotten about it.

He shrugged. ‘What is it about, then?’

‘Me. It’s about me, and what I want, for a change. And what I want is to be far away from you right now.’

I turned to leave the room but Paul caught my arm. ‘Not so fast. How can you want to throw away twenty-five years of marriage just like that? I thought we had a good, strong marriage!’

‘It was good in parts, Paul. I’m not throwing the past away. I’m just moving on. It feels like the right thing to do. For me.’

‘Not bloody right for me though, is it? Who’ll cook my dinner if you’re not here? Who’ll clean the house?’

‘Buy ready-meals and employ a cleaner,’ I replied, yanking my arm out of his grasp. That confirmed it. All he wanted me to stay for was to be his housekeeper. The sooner I left the better. I ran out of the room and upstairs, and began moving my things into the spare room. Paul hollered up the stairs after me, something about I’d regret it and come back with my tail between my legs, but I ignored it.

In the spare room I sat on the bed and let the tears come for a while. Paul did not come upstairs. I heard the TV being turned up. After a while I pulled myself together, took out my phone and texted the boys – It’s done. Told him. He’s not happy.

Jon texted back within minutes – Well done. Xxx. Love you.

And Matt rang me. ‘You OK?’

I sniffed. ‘Yes, I suppose so. I’ll be moving to Ireland as soon as I can.’

‘You can stay with me if you need to. I can sleep on my sofa.’

‘It’s OK. I need to be here to pack anyway.’

‘Here if you need me,’ he said, and once more I rejoiced in my strong, supportive and loving sons.

Next day I booked a car-ferry crossing from Holyhead to Dublin for Friday morning, then spent the rest of the day packing. Paul had been silent in the morning before work, barely acknowledging my presence. I knew it had been a shock for him, and I understood that he was hurting, but I had to do this. It’d be better for both of us in the long run. He’d find another Angie, sooner or later. As I thought this, I realised I didn’t care if he did. In fact, if it helped him let me go, it’d be better if he did take up with someone new quickly.

I came upstairs in the evening with a basket of clean washing, and caught Paul standing at the door to the spare room, looking at the half-packed boxes and suitcases I had strewn all over the floor.

‘You’re really doing this, then?’ he said, his voice flat and tight.

‘Yes.’