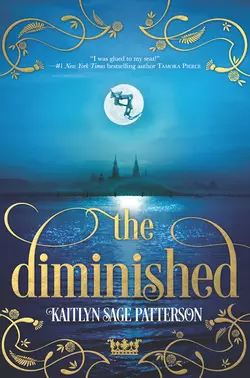

The Diminished

Kaitlyn Patterson

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Книги для подростков

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 697.37 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: In the Alskad Empire, nearly all are born with a twin, two halves to form one whole… yet some face the world alone.The singleborn.A rare few are singleborn in each generation, and therefore given the right to rule by the gods and goddesses. Bo Trousillion is one of these few, born into the royal line and destined to rule. Though he has been chosen to succeed his great-aunt, Queen Runa, as the leader of the Alskad Empire, Bo has never felt equal to the grand future before him.The diminishedWhen one twin dies, the other usually follows, unable to face the world without their other half. Those who survive are considered diminished, doomed to succumb to the violent grief that inevitably destroys everyone whose twin has died. Such is the fate of Vi Abernathy, whose twin sister died in infancy. Raised by the anchorites of the temple after her family cast her off, Vi has spent her whole life scheming for a way to escape and live out what’s left of her life in peace.As their sixteenth birthdays approach, Bo and Vi face very different futures—one a life of luxury as the heir to the throne, the other years of backbreaking work as a temple servant. But a long-held secret and the fate of the empire are destined to bring them together in a way they never could have imagined.