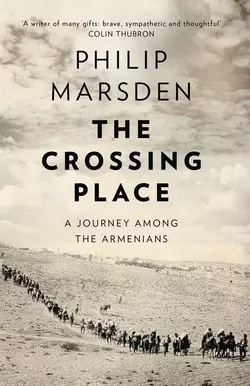

The Crossing Place: A Journey among the Armenians

Philip Marsden

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Отдых, туризм

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 866.61 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 17.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Ebook edition of Philip Marsden’s classic travel book, published to coincide with the centenary of the Armenian massacres.After centuries of prominence as a world power, Armenia has withstood every attempt during the 20th century to destroy it. With a name redolent both of dim antiquity and of a modern world and its tensions, the Armenians founded a civilization and underwent a diaspora that brought many of the great ideas of the East to Western Europe.The Crossing Place is Philip Marsden’s gripping account of his remarkable journey through the Middle East, Eastern Europe and the Caucasus in a quest to discover the secret of one of the world’s most extraordinary peoples.Caught between opposing empires, between warring religions and ideologies – at the crossing place of history – the Armenians have somehow survived against the odds. This is their story – told by one of the finest travel writers at work today.