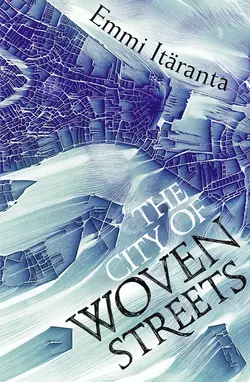

The City of Woven Streets

Emmi Itaranta

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 152.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ′Where itaranta shines is in her understated but compelling characters′ Red star review (for MEMORY OF WATER), Publishers Weekly.Emmi Itäranta’s prose combines the lyricism of Ishiguro’s NEVER LET ME GO. This is her second novel, following the award-winning MEMORY OF WATER.The tapestry of life may be more fragile than it seems: pull one thread, and all will unravel.In the City of Woven Streets, human life has little value. You practice a craft to keep you alive, or you are an outcast, unwanted and tainted. Eliana is a young weaver in the House of Webs, but secretly knows she doesn’t really belong there. She is hiding a shameful birth defect that would, if anyone knew about it, land her in the House of the Tainted, a prison for those whose very existence is considered a curse.When an unknown woman with her tongue cut off and Eliana’s name tattooed on her skin arrives at the House of Webs, Eliana discovers an invisible network of power behind the city’s facade. All the while, the sea is clawing the shores and the streets are slowly drowning.