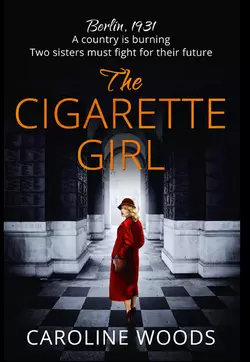

The Cigarette Girl

Caroline Woods

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 542.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: BERLIN, 1931: Sisters raised in a Catholic orphanage, Berni and Grete Metzger are each other’s whole world. That is, until life propels them to opposite sides of seedy, splendid, and violent Weimar Berlin.Berni becomes a cigarette girl, a denizen of the cabaret scene alongside her transgender best friend Anita, who is considering a risky gender reassignment surgery. Meanwhile Grete is hired as a maid to a Nazi family, and begins to form a complicated bond with their son whilst training as a nurse.As Germany barrels toward the Third Reich and ruin, both sisters eventually come to the same conclusion: they have to leave the country. And they will leave together. But nothing goes as planned as the sisters each make decisions that will change their lives, and their relationship, forever.SOUTH CAROLINA, 1970: With the recent death of her father, Janeen Moore yearns to know more about her family history, especially the closely guarded story of her mother’s youth in Germany. One day she intercepts a letter intended for her mother: a confession written by a German woman, a plea for forgiveness. What role does Janeen’s mother play in this story, and why does she seem so distressed by recent news that a former SS officer has resurfaced in America?