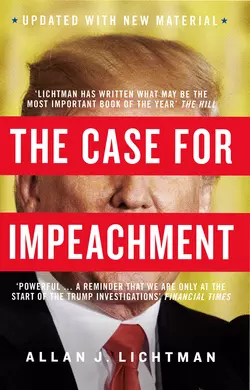

The Case for Impeachment

Allan J. Lichtman

Professor Allan J. Lichtman, who has correctly forecasted thirty years of presidential elections, makes the case for impeaching the 45th president of the United States, Donald J. Trump.Impeachment will ‘proceed from the misconduct of public men, or, in other words, from the abuse or violation of some public trust,’ and ‘they relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself. ’(Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist, 1788)In The Case for Impeachment, Professor Lichtman lays out the reasons why Congress removing Donald J. Trump has become a matter of ‘when’ not ‘if’. Shedding some light on the consequences of his ties with Russia before and after the election, complicated financial conflicts of interest at home and abroad and abuse of executive authority, this is an authoritative and comprehensive analysis of the most controversial presidency since Richard Nixon.

Copyright (#u02e1622b-9977-5a71-a43a-1d59df368cff)

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com (http://www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2017

First published in the United States by Dey Street Books in 2017

Copyright © Allan J. Lichtman 2017

Introduction © Allan J. Lichtman 2018

Cover photograph © Bloomberg/Getty Images

Cover design by Ploy Siripant

Allan J. Lichtman asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008292676

Ebook Edition 2018 © ISBN: 9780008257415

Version: 2018-05-23

Praise for The Case for Impeachment: (#u02e1622b-9977-5a71-a43a-1d59df368cff)

‘[Lichtman’s] book is a pretty substantial case for why Donald Trump should not have been president at all … A good backdrop for conversations that will likely remain a part of [the] national dialogue for some time’ New York Journal of Books

‘The US system takes a long time to gather speed. Once it does, it can be hard to stop’

Financial Times

Contents

Cover (#ub8d0e90d-3752-5805-8d31-c5a409d9c68d)

Title Page (#u72eeeabd-ab95-5567-a1f4-5c6d9b74b471)

Copyright

Praise for The Case for Impeachment

Author’s Note

Introduction

CHAPTER 1: High Crimes and Misdemeanors

CHAPTER 2: The Resignation of Richard Nixon: A Warning to Donald Trump

CHAPTER 3: Flouting the Law

CHAPTER 4: Conflicts of Interest

CHAPTER 5: Lies, Lies, and More Lies

CHAPTER 6: Trump’s War on Women

CHAPTER 7: A Crime Against Humanity

CHAPTER 8: The Russian Connections

CHAPTER 9: Abuse of Power

CHAPTER 10: The Unrestrained Trump

CHAPTER 11: Memo: The Way Out

CONCLUSION: The Peaceful Remedy of Impeachment

Notes

Acknowledgments

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Allan J. Lichtman (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher

Author’s Note (#u02e1622b-9977-5a71-a43a-1d59df368cff)

____________

Impeachment will “proceed from the misconduct of public men, or, in other words, from the abuse or violation of some public trust,” and “they relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself.”

—Alexander Hamilton, The Federalist, 1788

I began thinking about impeachment before the November 2016 election. For weeks, my students had been asking who I thought would be our next president, Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump. Finally, on a late evening in mid-September 2016, I leaned back in my chair and peered out into the hall at the mostly darkened offices of American University in Washington, D.C. I had just finished my analysis: Donald Trump would win the presidency. My forecast ignored polls, debates, advertising, tweets, news coverage, and campaign strategies—the usual grist for the punditry mills—that count for little or nothing on Election Day. I had used the same proven method that had led me to forecast accurately the outcomes of eight previous elections, and I’d kept my eye on the big picture—the strength and performance of the party holding the White House currently. After thirty-two years of correctly forecasting election results, even I was surprised by the outcome.

Among those who noticed my prediction was Donald J. Trump himself. Taking time out of preparing to become the world’s most powerful leader, he wrote me a personal note, saying, “Professor—Congrats—good call.” What Trump overlooked, however, was my “next big prediction:” that, after winning the presidency, he would be impeached.

Here I did not rely on my usual model, rather I used a deep analysis of Trump’s past and proven behavior, as well as the history of politics and impeachment in our country. In the short span of time between Trump’s election and this book’s publication in April 2017, his words and deeds have strengthened the case considerably. History is not geometry and historical parallels are never exact, yet a president who seems to have learned nothing from history is abusing and violating the public trust and setting the stage for a myriad of impeachable offenses that could get him removed from office.

America’s founders, who had so recently cast off the yoke of King George’s tyranny, granted their president awesome powers as the nation’s chief executive and commander-in-chief of its armed forces. Yet they understood the dangers of a runaway presidency. As James Madison warned during the Constitutional Convention, the president “might pervert his administration into a scheme of peculation or oppression” and “betray his trust to foreign powers,” with an outcome “fatal to the Republic.” To keep a rogue president in check, delegates separated constitutional powers into three independent branches of government. But knowing that a determined president could crash through these barriers, they also put in place impeachment as the rear guard of American democracy.

After exhaustive debate, the framers agreed on broad standards for impeachment and assigned this absolute power not to the judiciary, but to elected members of the U.S. House and Senate. By doing so they ensured that the fate of presidents would depend not on standards of law alone, but on the intertwined political, practical, moral, and legal judgment of elected officials. Hamilton explained that impeachments broadly cover “the abuse or violation of some public trust” and are properly “denominated POLITICAL.”

This book will escort you through the process and history of impeachment; as your warning about the dangers of Trump’s rogue presidency; and as your guide to the myriad transgressions that I predict will lead to his impeachment. I invite you to follow each chapter and decide for yourself when Trump has reached the critical mass of violations that triggers the implosion of his presidency.

In The Case for Impeachment, I’ll look beyond the daily news cycle of events which will have continued to evolve to focus on the big picture of the impeachment process and the Trump presidency. I’ll take you through constitutional debates and the gritty politics of past impeachments. I’ll explain how Trump threatens the institutions and traditions that have made America safe and free for 230 years, and I’ll make clear why a Republican Congress might impeach a president of its own party. I also include a personal memo to President Trump on how he might dispel the clouds of controversy overhanging his presidency and avoid impeachment. I am not calling here for a witch hunt against an unconventional presidency or for snaring Trump on some minor or technical violation. The point is to assess at what point impeachment becomes necessary to protect America’s constitutional liberties and the vital interests of the nation. An impeachment of a president need not imperil the institution of the presidency. “The genius of impeachment,” said historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. is “that it could punish the man without punishing the office.”

The impeachment of an American president is rare, but not exceptional. The U.S. House of Representatives has impeached two presidents, Andrew Johnson in 1868 and Bill Clinton in 1998; another, Richard Nixon, only averted impeachment with a timely resignation. Counting Nixon, one out of every fourteen U.S. presidents have faced impeachment. Gamblers have become rich betting on longer odds than that.

But forget historical odds. Trump has broken all the usual rules of politics and governing. Early in his term, he has stretched presidential authority nearly to the breaking point, appointed cabinet officials dedicated to destroying the institutions they are assigned to run, and pushed America toward legal and constitutional crises.

No previous president has entered the Oval Office without a shred of public service or with as egregious a record of enriching himself at the expense of others. Trump’s penchant for lying, disregard for the law, and conflicts of interests are lifelong habits that will permeate his entire presidency. He has a history of mistreating women and covering up his misdeeds. He could commit his crime against humanity, not directly through war, but indirectly by reversing the battle against catastrophic climate change, upon which humanity’s well-being will likely depend. His dubious connections to Russia could open him to a charge of treason. His disdain for constitutional restraints could lead to abuses of power that forfeit the trust of even a Republican Congress.

What are the ranges and limitations of presidential authority in a system of separated power? What are the standards of truthfulness that a president must uphold? Where should the line be drawn between public service and private gain? Can a free press continue to function in the United States? How can America guard against foreign manipulation of its politics? What responsibility does the president have to protect the earth and its people from catastrophic climate change? When should impeachment be invoked or restrained? These are timeless issues that will decide the future of American democracy. The case for impeaching Donald Trump must be situated in the history of past impeachments—but if you’re really anxious, you can jump ahead to chapter 3 and start right in on Donald Trump.

In his inaugural address, Trump slammed his favorite target, Washington politicians. “For too long,” he said, “a small group in our nation’s capital has reaped the rewards of government while the people have borne the costs.” Yet this small group holds in their hands the power to impeach and remove the forty-fifth president.

It is our responsibility to arm ourselves with the knowledge needed to protect our great nation and keep alive its most precious traditions. Already millions of Americans and many more people worldwide have risen in protest against the dangerous presidency of Donald Trump. His impeachment will be decided not just in the halls of Congress but in the streets of America.

Introduction (#u02e1622b-9977-5a71-a43a-1d59df368cff)

____________

The Trump administration is awash in investigations, by Special Counsel Robert Mueller, the U.S. House and Senate Intelligence Committees, and the Senate Judiciary Committee. There’s hope to be found in these inquiries. Still, it is past time for the investigation that matters most to President Donald Trump and the American people: an impeachment investigation by the House Judiciary Committee. This committee investigates potential impeachable offenses and decides whether to recommend articles of impeachment to the full House, which possesses the sole constitutional authority necessary for impeaching a president. If impeached, the U.S. Senate has the authority to remove the president from office by a two-thirds vote.

To date, in early November 2017, much new public evidence has emerged that points to collusion between the Trump team and the Russians. Meanwhile, President Trump has ignored nearly all my earlier advice on how to avoid impeachment, choosing instead to endeavor to obstruct the Russia investigation, exacerbate his conflicts of interest, edge closer to committing a crime against humanity on climate change, and continue his abuse of presidential power. Trump’s transgressions have reached the point where Congress must assess whether he poses a clear and present danger to America’s national security and the freedom and liberties of her people.

An impeachment investigation should not turn on disputes over the president’s style or policies, but only on what Alexander Hamilton termed “the abuse of violation of some public trust” that leads to “injuries done immediately to the society itself.” By placing the power to impeach in an elected body, the framers recognized that the assessment of impeachable offenses demands moral, legal, and political judgment.

THE RUSSIAN CONNECTION

The Russian sword of Damocles now hangs over this administration by the slenderest of threads. Despite repeated claims of innocence from Trump and his associates, they’ve engaged in a recurring pattern of deception concerning their ties to the Russians. They conceal and lie, and then when caught, claim that all contacts were innocuous. The publicly known evidence for collusion between the Trump team, and perhaps Trump himself, and the Russians is circumstantial, but powerful. Many Americans have been indicted and convicted of serious crimes based on circumstantial evidence.

The most compelling evidence of collusion comes from a previously undisclosed meeting between Kremlin-connected Russians and the highest echelons of the Trump campaign—son Donald Trump Jr., son-in-law Jared Kushner, and then–campaign manager Paul Manafort. According to email evidence, the meeting in question was set up by Rob Goldstone, the manager for pop singer Emin Agalarov, who is the son of Russian oligarch Aras Agalarov. Trump had previously sought to partner with the elder Agalarov—a close ally of President Vladimir Putin—on ambitious real estate deals in Russia.

GOLDSTONE TO TRUMP JR., JUNE 3, 2016

Emin just called and asked me to contact you with something very interesting.

The Crown prosecutor of Russia met with his father Aras this morning and in their meeting offered to provide the Trump campaign with some official documents and information that would incriminate Hillary and her dealings with Russia and would be very useful to your father.

This is obviously very high level and sensitive information but is part of Russia and its government’s support for Mr. Trump – helped along by Aras and Emin.

What do you think is the best way to handle this information and would you be able to speak to Emin about it directly?

I can also send this info to your father via Rhona, but it is ultra sensitive so wanted to send to you first.

TRUMP JR. TO GOLDSTONE, JUNE 3, 2016

Thanks Rob I appreciate that. I am on the road at the moment but perhaps I just speak to Emin first. Seems we have some time and if it’s what you say I love itespecially later in the summer. Could we do a call first thing next week when I am back?

GOLDSTONE TO TRUMP JR., JUNE 7, 2016

Emin asked that I schedule a meeting with you and The Russian government attorney who is flying over from Moscow for this Thursday.

TRUMP JR. TO GOLDSTONE, JUNE 7, 2016

Great. It will likely be Paul Manafort (campaign boss) my brother in law and me, 725 Fifth Ave 25th floor.

Based on this email chain and subsequent meeting, “it’s now established that the campaign was aware of, and involved in, Russian attempts to meddle in the election,” said Cornell University law professor Jens David Ohlin. “The only question now is whether President Trump was personally involved or not.” Another authority, Michigan law professor Samuel Gross, said, “This is beginning to look a lot like a criminal conspiracy … You can be indicted on less evidence than this.”

Donald Trump Jr. lied multiple times about the Russia meeting, both before and after its disclosure. In March 2017, Trump Jr. told the New York Times, “Did I meet with people that were Russian? I’m sure, I’m sure I did. But none that were set up. None that I can think of at the moment. And certainly none that I was representing the campaign in any way, shape or form.”

On July 8, after the Times broke the story of the June 9 meeting, Trump Jr. commented, “It was a short introductory meeting. I asked Jared and Paul to stop by. We primarily discussed a program about the adoption of Russian children that was active and popular with American families years ago and was since ended by the Russian government, but it was not a campaign issue at the time and there was no follow up.”

Then, after the Times indicated on July 10 that it had in its possession the email chain for the meeting, Trump Jr. again changed his story, this time issuing a tweet that said, “Obviously [not] the first person on a campaign to ever take a meeting to hear info about an opponent … went nowhere but had to listen.” Despite that claim, he never did cite any examples of other leaders of a presidential campaign meeting with representatives of a hostile foreign power to amass incriminating data on their opponent.

Moments before the Times reported on the existence of the emails, Trump Jr. preemptively released them, saying he was being “totally transparent”—this after months of dissembling. That same day, he told Sean Hannity of Fox News that nothing else of significance would emerge about the meeting. “This is everything,” Trump Jr. said. But “everything” it was not. The press discovered that several more Russians had attended the meeting than Trump Jr. had disclosed, including Irakly Kaveladze, who was well known for moving money into the United States for wealthy Russians. Kaveladze attended as a representative of Aras Agalarov, whom Goldstone had identified as having met with Russia’s “Crown prosecutor” and having received her offer to provide incriminating information about Clinton. Also present was Rinat Akhmetshin, a Russian immigrant to the States with connections to Russia’s oligarchs and the Kremlin.

Even Donald Trump Jr.’s best attempt at impersonating the naïve American ignorant of all things Russian wouldn’t have been enough to fool the American people. In 2008, he’d bragged that “Russians make up a pretty disproportionate cross-section of a lot of our assets,” and just months before the June 2016 meeting, the Trump Organization was in hot pursuit of a real estate deal in Moscow.

Donald Trump Jr. denied having participated in telephone calls about the meeting, but phone records revealed that several such calls were indeed held between him and Emin Agalarov. Trump Jr. insisted to Senate investigators that he had no recollection of the content of those conversations. He said that the meeting was so inconsequential that Manafort was on his phone for most of it. But Manafort was not making outside calls; he was using his phone to take meeting notes.

According to Donald Trump Jr., he’d maintained no more than a “casual relationship” with Goldstone since the two first met in 2014. Yet, in one of the most important but overlooked emails, Goldstone disclosed much deeper ties to the Trumps. Goldstone reveals that he had direct inside access to Donald Trump Sr. “via Rhona.” Rhona Graff is a multi-decade Trump loyalist and assistant, who, according to an article published in Politico well after the June 2016 meeting, was a conduit to Trump Sr. for “longtime friends and associates,” not casual acquaintances. Goldstone even addresses Trump’s gatekeeper by her first name only. This purported connection raises serious questions about direct collusion between candidate Trump and the Russians.

Donald Trump Jr. assured Hannity that he did not tell his father about the meeting. Yet White House press secretary Sarah Huckabee Sanders confirmed that three days before the Hannity interview, President Trump had “weighed in as any father would” on drafting Trump Jr.’s initial misleading account of the meeting. The Washington Post reported without contradiction from the White House that President Trump did more than just “weigh in”; he dictated the statement while aboard Air Force One, en route to Washington from a meeting in Germany. The big question is when Trump Sr. learned of the June 2016 meeting. If he learned about it only after the media broke the story more than a year later, his input on the misleading memo could still expose him to an obstruction of justice charge. If he knew about the meeting at the time it took place, then he could be subject to charges of collusion with the Russians as well.

Once more, Trump Jr. changed his story—this time in written testimony presented to the Senate Intelligence Committee. His latest explanation: “To the extent they [the Russians] had information concerning the fitness, character or qualifications of a presidential candidate, I believed that I should at least hear them out … Depending on what, if any, information they had, I could then consult with counsel to make an informed decision as to whether to give it further consideration.” He claimed, however, that the Russians provided “no useful information” about Clinton, adding that “at this time [June 2016] there was not the focus on Russian activities that there is today.” Trump Jr. denied any recollection of his father’s participation in drafting his initial statement on the June 9 meeting.

Regarding his exclamation of “I love it” in the flurry of emails exchanged with Goldstone, Trump Jr. explained that “it was simply a colloquial way of saying that I appreciated Rob’s gesture.” That Trump Jr. expected anyone to believe those words of enthusiasm were not a direct response to the Russian government’s offer to help elect his father and provide incriminating information on Clinton is really quite incredible. In his message to Goldstone, Trump Jr. had remarked that the information would be especially useful “later in the summer,” when he expected the Republican National Convention to nominate Trump as the party’s presidential candidate.

The questions raised by Trump Jr.’s series of ever-changing accounts are extensive and pressing. Who of sound mind could believe that the Russians were a reliable and objective source on “the fitness, character, or qualifications of a presidential candidate,” especially when the stated purpose of the meeting was to provide intel on Clinton so damning that it might sway the election in candidate Trump’s favor? And by what means other than illegal spying and thievery could the Russians have obtained such previously undisclosed dirt on Clinton?

If the meeting was of so little consequence, why did its participants shroud it in secrecy for so long? Why the rush to consult with lawyers after the fact if nothing about the meeting had a whiff of potential illegality? Why didn’t an email saying that the meeting invitation was “part of Russia and its government’s support for Mr. Trump” set off loud alarm bells for the candidate’s son? Why didn’t Trump Jr. immediately report this evidence of probable foreign meddling in the election to the FBI? Why did Donald J. Trump Sr. say in campaign rallies immediately after the meeting that damaging information on Clinton would be forthcoming? How did Trump Jr. forget about the president’s involvement, just a couple of months earlier, in drafting his critical first statement about the meeting? These lies are potentially relevant to Trump Sr.’s impeachment if Trump Jr. was protecting his father from contemporary knowledge of the June 2016 meeting.

Ask John Sipher and Steve Hall, two former CIA officials who served under Republican and Democratic administrations, and they’ll tell you that the June 9 meeting had all the hallmarks of a recruitment operation by Russian intelligence. Sipher and Hall posited that, once the Russians unearthed derogatory material by hacking into the emails of the Democratic National Committee, they “might then have seen an opportunity for a campaign to influence or disrupt the election.” When Trump Jr. responded with “I love it” to Goldstone’s “fishing” email, “the Russians might well have thought that they had found an inside source, an ally, a potential agent of influence on the election.”

In a standard pattern for Russian intelligence, they “employed a cover story—adoptions—to make it believable to the outside world that there was nothing amiss.” They used “cutouts, nonofficial Russians, for the actual meeting, enabling the Trump team to claim—truthfully—that there were no Russian government employees at the meeting and that it was just former business contacts of the Trump empire.” Thus, “when the Trump associates failed to do the right thing by informing the FBI, the Russians … knew what bait to use and had a plan to reel in the fish once it bit.” Sipher and Hall posit that while a Russian operation to disrupt American society and politics “is certainly plausible, it is not inconsistent with a much darker Russian goal: gaining an insider ally at the highest levels of the United States government.”

There are yet more new revelations in the never-ending Russia story. In July 2016, when the Russia story first heated up, Donald Trump Sr. flatly declared, “I have nothing to do with Russia—for anything.” He said this despite his business partnerships with Russia-connected interests, his lengthy quest to develop Trump-branded ventures in Russia, and the Trump trademarks in Russia, six of which the Russian government renewed in 2016 at then-candidate Trump’s request. Recently, the press discovered that Trump Sr. sought to complete a real estate deal in Moscow while campaigning for president, even signing a nonbinding letter of consent to pursue it.

Trump’s lawyer, Michael Cohen, and the ubiquitous Felix Sater were the prime movers of this ultimately failed deal—two of the three men who, according to the New York Times, presented a plan to lift the Ukrainian sanctions on Russia to then–National Security Advisor Michael Flynn. In a November 2015 email to Cohen, Sater bragged about the deal and how his ties to Putin would get Trump elected: “Michael I arranged for Ivanka to sit in Putins [sic] private chair at his desk and office in the Kremlin. I will get Putin on this program and we will get Donald elected … Buddy our boy can become President of the USA and we can engineer it. I will get all of Putins [sic] team to buy in on this [emphasis added].” It’s entirely possible that Sater was exaggerating his influence in the Kremlin; then again, the New York Times did report that Ivanka had indicated it was possible she’d sat in Mr. Putin’s chair during her Moscow trip in 2006, though she couldn’t recall. The eerie similarity, too, between Sater’s message to Cohen about Russians helping to elect Trump, and the message sent by Goldstone to Trump Jr. suggests that Sater’s claim may not have been the benign “puffery” that Cohen would later purport it to be.

We have since learned that during this transition period and his White House tenure, Kushner engaged in several other dubious activities that merit investigation. Kushner secretly met with Russian Ambassador Sergey Kislyak to explore establishing a back channel between the Trump transition team and the Kremlin using Russian facilities. He met with the head of a Russian state bank that was under U.S. sanctions. He met with the King of Jordon to promote a deal on providing nuclear reactors to Middle Eastern nations that included both American and Russian business interests. Russia’s involvement had apparently diminished over time, but was not necessarily eliminated at the time of the meeting according to news reports. And we first learned through a Politico report on September 24, 2017, that in December 2016 Kushner set up a private email account that he used for some official government business—this after Trump had spent more than a year excoriating Clinton for her use of a private email server, even encouraging chants of “lock her up!” Predictably, Kushner’s lawyer said that these email communications were few and innocuous. According to the New York Times, at least five other close Trump advisers, including Ivanka Trump and former chief strategist Steve Bannon, “occasionally used private email addresses to discuss White House matters.” Again, this is not nearly the complete story. New reporting indicates that Kushner and Ivanka Trump had another private email account that received hundreds of White House emails.

In July 2016, Manafort, in a series of email exchanges with an intermediary in Ukraine, offered privileged access to the Trump campaign to Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska, whom I identified in April as a former business partner of Manafort’s and one of Putin’s closest confidants. “If he needs private briefings we can accommodate,” Manafort wrote. Manafort spokesman, Jason Maloni, said that the email exchanges were “innocuous” and involved only an attempt by Manafort to collect on a debt owed to him by Deripaska. But press reports indicate it was Deripaska who believed that Manafort owed him payments from a failed business deal, which Manafort implicitly verified, saying, “How do we use to get whole?”—apparently from his obligations to Deripaska. Reporting by NBC News indicates that Deripaska transmitted some $60 million in loans to companies linked to Manafort. The Trump team has set the Guinness world record for undisclosed but allegedly “innocuous” activities involving a foreign adversary.

Like the June 9 meeting, this incident involving Manafort and Deripaska had the signs of a “classic intelligence operation being run by the Russians,” said Glenn Carle, who worked for more than twenty years in the Clandestine Services of the CIA. “Approach someone with access and influence, propose benign-seeming justifications, offer an enticement [like forgiving a debt], get benign-seeming favors done by the target in exchange (e.g., a meeting, a briefing, information that seems non-alarming), and use the meeting to entice down the primrose path.”

Some scholars and journalists have asserted that President Trump could not be charged with treason even if he colluded with the Russians, or charged with misprision of treason if he failed to report collusion, saying that treason can be charged “only during a state of war.” Yet the American intelligence community has established that Russia did engage in acts of war against America during the 2016 presidential campaign. This was a modern form of warfare, carried out not with bullets and bombs, but via a cyberattack on the foundations of American democracy. According to the Gerasimov Doctrine, a 2013 paper written by General Valery Gerasimov, chief of the general staff of Russia’s Armed Forces, “the very ‘rules of war’ have changed. The role of nonmilitary means of achieving political and strategic goals has grown, and, in many cases, they have exceeded the power of force of weapons in their effectiveness.”

If Trump did, in fact, collude with the Russians, he likely violated other federal criminal laws in addition to treason. These include, but may not be limited to, the Logan Act, which forbids private persons from negotiating with a foreign power; a federal election law that bans campaigns from knowingly soliciting or accepting anything of value from foreign nationals; and the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, which prohibits any aiding or abetting of illegal computer hacking.

The Russian attack on the U.S. presidential campaign turned out to be more widespread and nefarious than first believed. After an inexplicable eight-month delay, Trump’s Department of Homeland Security revealed in September 2017 that the Russians sought to hack into the registration rolls of twenty-one states, and in some cases, may have succeeded. They also ran thousands of paid, targeted political ads on Facebook. Investigators are probing whether the targeting insights they acted on came from the Trump campaign. Kushner, who took the lead in developing the campaign’s social media operation, is on the record as having said, “I called somebody who works for one of the technology companies that I work with, and I had them give me a tutorial on how to use Facebook micro-targeting.” Special Counsel Mueller has obtained a warrant for Facebook records, meaning he’s convinced a federal judge that there exists probable cause of criminal violations.

Beyond denying any collusion with the Russians, Trump also contradicted the findings of the American intelligence community—under both Obama’s and his presidency—with his claim that Russia did not meddle in the 2016 campaign on his behalf. On September 22, 2017, he said, “No, Russia did not help me, that I can tell you, OK?” Any claim to the contrary, he added, “was one great hoax.” This presidential denial carries fateful consequence for the country, in that the Trump administration is doing little or nothing to protect America from future attacks on its democracy by foreign adversaries. Rather than establishing an independent commission to recommend means for safeguarding our democracy, Trump instead set up a “fraud” commission to validate his bogus claim that between three and five million illegal voters denied him a popular vote victory.

On October 30, 2017, Special Counsel Mueller unsealed indictments of Manafort and his associate Rick Gates, and a guilty plea by former Trump campaign foreign policy advisor George Papadopoulos. Emails from the Papadopoulos plea showed an openness by top campaign officials to collude with the Russians. His testimony establishes that Trump was present at a meeting when Papadopoulos proposed using his Russian connections to set up a Trump-Putin meeting. Papadopoulos further testified that in April 2016, one of his Russian contacts told him, “They [the Russians] have dirt on her;” “the Russians had emails of Clinton;” “they have thousands of emails.” Along with the Goldstone and Sater emails, this is the third time that Russians communicated to Trump associates intending to help Trump win the election.

OBSTRUCTION OF JUSTICE

Among those who speak of scandal, there exists a popular mantra—“the cover-up is worse than the crime.” Catchy as it may sound, it’s a saying that risks trivializing the significance of possible collusion between Trump’s campaign and America’s Russian adversaries. It also plays into the hands of Trump and his backers, who’ve hinted that, even if collusion did transpire, its occurrence was not a serious matter. For example, referring to the June 9 meeting, Trump Sr. said, “Most people would have taken that meeting … it’s very standard.” If such conduct were ever to become standard, American democracy would suffer a grievous, perhaps even fatal blow.

Nonetheless, and based on publicly available information only, there is now at least as robust an obstruction of justice case against President Trump as there was against President Clinton. The difference is that, this time, it’s on a vastly more consequential matter than a consensual, personal affair. The cover-up began early in Trump’s term, when he delayed firing then–National Security Advisor Michael Flynn for eighteen days after the Acting Attorney General had warned that the Russians likely compromised Flynn. Since vacating his position, Flynn has said that he has “a story to tell,” a story that Trump likely hopes to keep untold.

To derail the House Intelligence Committee’s Russia investigation, Trump’s White House worked with Committee Chairman Devin Nunes, who served on Trump’s transition team. In private, Trump reportedly asked CIA Director Mike Pompeo to influence the FBI into backing off the Russia investigation. Former FBI Director James Comey testified under oath that Trump asked him for personal loyalty and to “let go” of the Flynn investigation. Trump then fired Comey, only admitting at a later point that he’d had “Russia on his mind” in doing so. He has since engaged in a campaign to discredit Comey, even breaching the separation between the White House and Justice Department by having his press secretary recommend that federal prosecutors consider indicting Comey—a potential witness against Trump—for using an FBI computer to type personal memos about these exchanges with the president. And, as already touched upon, Trump drafted or participated in drafting the misleading response to the June 9 meeting.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Trump has not merely failed to divest himself from his domestic and foreign business interests, he has enmeshed himself even further in arguably unconstitutional conflicts of interest. In likely violation of the Constitution’s Foreign Emoluments Clause, in June 2017 Trump gained preliminary approval from China for nine potentially lucrative Trump trademarks that it had previously rejected. The Trump International Hotel in Washington, D.C., has become a magnet for foreign interests, who rent rooms and hold events on its grounds. Trump has claimed that he will hand over to the U.S. Treasury any hotel profits from these foreign governments, but he failed to indicate how he will calculate revenue above costs.

In violation of Trump’s pledge to launch no new foreign ventures, his organization has partnered with billionaire Hussain Sajwani to develop the Trump Estates Park Residences in Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Ongoing projects also enmesh Trump in potentially serious conflicts of interest. In Azerbaijan, one of the world’s most corrupt countries, Trump has entered into a development deal with Anar Mammadov, the son of the nation’s transportation minister. A Trump residential building and an office tower, funded by unknown investors whose money came through banks in Cyprus and Mauritius, is scheduled for completion during the next five years in a suburb of New Delhi, India. In Indonesia, Trump has launched two projects: a resort near Jakarta, and Trump International Hotel and Tower Bali. Trump’s partner, the billionaire Hary Tanoesoedibjo, has founded a new political party in his country and expressed an interest in emulating Trump by running for president of his nation. In Scotland, meanwhile, Trump’s company is embroiled in a permit dispute with the environmental agency over the development of a second golf course near Aberdeen. These and other foreign ventures likely violate the constitution, whether through the direct or indirect involvement of foreign officials and their patronage of Trump properties, or through their granting of discretionary permits, tax breaks, complementary infrastructure development, regulatory easements, and other concessions.

A lawsuit, filed by the attorneys general of the District of Columbia and Maryland in June 2017, has called attention to President Trump’s violations of the Constitution’s Domestic Emoluments Clause. Recall, though, that the courts have no power to order impeachment, that authority rests solely with the U.S. House. According to Article 2, Section 1, Clause 7 of the Constitution, known as the Domestic Emoluments Clause, “The President shall, at stated Times, receive for his Services, a Compensation, which shall neither be increased nor diminished during the Period for which he shall have been elected, and he shall not receive within that Period any other Emolument from the United States, or any of them (emphasis added).” This means that, beyond his salary, the president cannot receive anything of value from the federal government or any state or local government.

The framers advisedly applied this prohibition only to the president. As Alexander Hamilton explained, the Domestic Emoluments Clause ensures that the federal and other governments “can neither weaken his fortitude by operating on his necessities, nor corrupt his integrity by appealing to his avarice.” Like the Foreign Emoluments Clause, its prohibition is absolute, with no quid pro quo specified.

As president, Donald Trump has received and continues to receive unconstitutional domestic emoluments. According to an investigation by Reuters, state and municipal pension funds in at least seven states have made substantial investments in the CIM Group, and pay the Group a few million dollars in quarterly fees to manage those investments, including the controversial Trump SoHo Hotel Condominium in Manhattan. In exchange for managing and marketing the property, says Reuters, “In 2015 and the first five months of 2016, Trump International Hotels Management LLC drew at least $3.1 million from the SoHo, and Trump received $3.3 million in income from the hotel management company, hotel records and campaign filings show.” Thus, “it’s a payment chain from state pension funds to President Trump,” said Jed Shugerman, Professor of Law at Fordham University. “This looks like an emolument to me.”

Trump built his business empire on concessions from local governments, and at least one of these emoluments, a New York City tax abatement for his Grand Hyatt Hotel, has persisted through his presidency. An analysis by the New York City Finance Department conducted for the New York Times found that in 2016, the tax break, which continues for another four years, netted Trump $17.8 million. That’s just one example of the tax breaks and lease arrangements from government that pose a constitutional violation. Trump has an application pending for a $32 million historic preservation tax credit for his Trump International Hotel in D.C., which he built on the bones of the famous Old Post Office building. The National Park Service, a federal agency under Trump’s control, must give final approval for this application.

Trump likely received another form of federal emolument when his appointed head of the General Services Administration (GSA) approved his continuing hold on a lease to the Old Post Office property, thereby maintaining his privilege to own, operate, and profit from the hotel. Yet the terms of the lease state, “No member or delegate to Congress, or elected official of the Government of the United States or the Government of the District of Columbia, shall be admitted to any share or part of this Lease, or to any benefit that may arise therefrom.” Designed to avoid conflicts of interest between the GSA, which administers the lease, and other government officials including the president, the provision is not gratuitous. In what could be viewed as a strategic maneuver, Trump appointed a former member of his transition team as the GSA’s Administrator. This Administrator then approved the lease arrangement, which effectively rendered the president the simultaneous tenant and landlord of the property.

When it comes to Trump’s conflicts with the Domestic Emolument Clause, some violations—like the direct payments made by the federal government to Trump-branded businesses—are especially glaring. The federal government has likely spent substantial sums at the Trump-branded golf resorts, for instance, that Trump has visited many times since his inauguration. The exact amount spent is unknown, because the administration has not responded to a request by congressional Democrats for an itemized accounting. In another textbook case of the types of conflict that framers sought to avoid, the Secret Service rented out space in Trump Tower. They’ve since withdrawn in early July, but only because of a dispute with management over the terms of their lease.

A CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY

Scientists have long warned that climate change poses a threat to humanity’s well-being and survival, and yet there are those who still insist on denying it. “There is no morally responsible way to downplay the dangers that negligent policies—expected to accelerate human-caused climate change—pose to humankind,” said Lawrence Torcello, an associate professor of moral and political philosophy at the University of Rochester. “There can be no greater crime against humanity than the foreseeable, and methodical, destruction of conditions that make human life possible … We will search in vain for a better reason to depose elected officials.”

I am not advocating impeachment over a policy difference, but rather saying that impeachment should take place only upon proof that President Trump’s retreat on climate change threatens the well-being and survival of humanity. As I previously explained, crimes against the environment as a form of genocide are well recognized in international law. Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria have inarguably brought the tragedies of climate change home to the American people, and yet, in their wakes, the statements issued by Trump have been contradictory. “Hurricane Irma is of epic proportion, perhaps bigger than we have ever seen,” Trump tweeted. But when asked to comment about recent storms and climate change, Trump contradicted himself, saying, “We’ve had bigger storms than this,” referring vaguely to storms that occurred in the 1930s and ’40s. Trump is “just not correct,” said meteorology professor Kerry Andrew Emanuel, an authority on hurricanes. Harvey soaked Texas and Louisiana with a record 51 inches of rainfall, and Irma was the most sustained Category 5 hurricane on record. The bill for these storms may top $200 billion, far exceeding the cost of any two storms in U.S. history. Following closely in their wake, Maria obliterated Puerto Rico and shattered historical precedent in the process. Never in recorded history had three Atlantic hurricanes of at least Category 4 force made landfall in a single year—until 2017.

It would be false to claim that climate change creates hurricanes, but warmer water temperatures do strengthen hurricanes, thereby increasing their intensity, and rising sea levels make for more severe storm surges. This toxic mix is a recipe for the perfect catastrophic storm. “The most dangerous myth that we have bought into as a society is not the myth that climate isn’t changing or that humans aren’t responsible,” said Katharine Hayhoe, director of the Climate Science Center at Texas Tech University. “It’s the myth that ‘It doesn’t matter to me.’ And that’s why this is absolutely the time to be talking about the way climate change amplifies or exacerbates these natural events. This brings it home.”

And the effects of climate change are not limited to destructive storms; they’ve also given us droughts, heat waves, record floods, and runaway wildfires like those that have claimed dozens of lives in California. New studies carry dire warnings for our future. A September 2017 study by NASA researchers found that warming Antarctica waters recently led to a tripling of the amount of ice loss. The greater the ice melt, the more that sea levels will rise. A July 2017 study by the Union of Concerned Scientists warned that 90 American communities already face chronic flooding and that this number will likely rise to 170 by 2035 and to 490 by 2100. At century’s end, chronic flooding will afflict “40 percent of all oceanfront communities on the East and Gulf Coast,” including Cambridge, Massachusetts; Oakland, California; Miami and St. Petersburg, Florida; and four of the five boroughs of New York City. If, however, the world met the emission reduction goals of the Paris Accord, which Trump has repudiated, the great majority of U.S. communities (380 of 490) could avoid this grim, watery fate.

In June 2017, Trump followed through on his promise to withdraw the United States from the Paris climate accord. Rumors circulating in September that Trump might be reconsidering his decision sparked hope among the environmentally minded, but the White House was quick to deny them. Climate Advisers has quantified the “Trump Effect” from his retreat on climate change as equaling by 2025 an enormous annual increase of nearly half a gigaton of new greenhouse gas pollution.

ABUSE OF POWER

In a 1987 decision, the Supreme Court recognized that judicial contempt vindicated the authority of the courts and protected the separation of powers: “Thus, although proceedings in response to out-of-court contempts are sufficiently criminal in nature to warrant the imposition of many procedural protections, this does not mean that their prosecution can be undertaken only by the Executive Branch, and it should not obscure the fact that the limited purpose of such proceedings is to vindicate judicial authority.”

Since assuming office, Trump has exploited his presidential power in flagrant disregard for this concern. Recall the contentious case of former Arizona sheriff Joe Arpaio, who was found guilty by a federal judge of criminal contempt for disregarding a court order to cease targeting and detaining suspected undocumented immigrants based on racial profiling—a violation of the constitutional rights of Hispanics. Trump asked his Justice Department to dismiss the case and then pardoned Arpaio, prior to sentencing and without the standard Justice Department review. In the history of our nation, no other president has ever fully pardoned someone convicted of criminal contempt prior to sentencing.

Trump has continued his assault on the free press, even retweeting and then deleting a violent image of a train smashing into a man with the CNN logo covering his face. At a campaign rally, he abused the power of the presidency to call on NFL owners to fire any players who exercised their right of peaceful protest by kneeling during the playing of the National Anthem. Bluntly put, President Trump had shattered precedent by using the power of his office to say that “those people,” whom he called “son[s] of bitch[es],” oblivious or maybe not to the slur on their mothers, should lose their livelihood for a nonviolent, principled protest.

To date, Republican indifference to revelations of President Trump’s transgressions have blocked prospects for an impeachment investigation. Yet there remain so many real possibilities for a change of direction that the odds still favor an impeachment investigation no later than the beginning of 2019, but likely sooner than that. Early January 2019 marks the seating of a new Congress. An impeachment investigation would quickly follow if Democrats recapture the U.S. House of Representative in the 2018 midterm elections. To date that remains a long-shot result, but political calculations are rapidly changing in the era of Trump, and the party holding the White House typically loses dozens of seats in midterm contests. Midterm voters usually turn out to register their opposition to an incumbent president, especially one with the dismal approval ratings of Donald Trump. It would take only a net gain of some two dozen seats for Democrats to regain the House majority they held until the 2010 elections.

Even barring such a political turnabout, the Mueller investigation, although not directly targeting impeachment, could issue findings damning enough to jolt the two dozen House Republicans into joining with Democrats for a majority vote on an impeachment investigation. Prosecutors use such pressure on underlings to cut immunity deals for testimony against the person at the top of the chain, in this case President Donald Trump. If Mueller flips high Trump officials, and their testimonies against Trump are damning enough, it could inspire public demands for an impeachment investigation and shock Republicans into action.

The president could pardon anyone subject to federal prosecution. However, such pardons pose the risk of making the obstruction of justice case against him compelling enough for many Republicans. “Unlike the pardon of Arpaio, which is a despicable blow to the rule of law,” said law professor Peter Shane of Ohio State University, “pardoning anyone who might have been a co-conspirator in misconduct involving Trump himself would much more plausibly be impeachable.”

Similarly, Mueller may uncover direct “smoking gun” evidence of collusion through intercepted conversations between members of the Trump team and the Russians. We know that American intelligence agents have wiretapped Manafort’s phones pursuant to a warrant from the U.S. Federal Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court, which requires probable cause that he was acting as a hostile foreign agent. Such evidence, like the Nixon tapes, could prove collusion from the mouths of the conspirators themselves and create unstoppable momentum for an impeachment investigation.

Lastly, Mueller could uncover proof of other felonies committed directly by Donald Trump. If he finds, for example, that the evidence supports allegations of obstruction of justice, money laundering, or tax evasion, even House Republicans would be hard-pressed to oppose an impeachment investigation. Mueller has been investigating obstruction and CNN has reported that “the IRS is now sharing information with special counsel Robert Mueller about key Trump campaign officials,” although it is unclear whether he has yet sought to obtain the president’s tax returns. The mills of special counsel investigations typically grind slowly, but Mueller seems intent on moving quickly. Bombshell revelations could occur by early 2018 or even sooner.

The final scenario turns on the self-interest of House Republicans. The first rule of politics for an incumbent officeholder is survival. If, by the summer of 2018, vulnerable Republicans come to believe that Trump threatens their reelection and see that the American people are demanding impeachment, enough of them could turn against the president and join with Democrats in support of an impeachment investigation.

Americans can only hope that, as in Watergate, patriotic Republicans will grasp the dire consequences of failing at least to investigate the impeachment of Donald Trump. Inaction would nullify constitutional safeguards against the corruption of presidential service through the pursuit of private profit. It would leave our democracy vulnerable to destruction by the undeterred foreign manipulation of elections abetted by the collusion of unscrupulous campaigns. Inaction would normalize the Orwellian doublethink of the Trump regime, in which reality no longer exists and lies become truth. It would validate the divisive politics that threaten America’s national unity by inflaming ethnic, racial, and religious prejudice.

There are yet deeper issues raised by Donald Trump’s impeachment. In his first speech to the United Nations, on September 19, 2017, Trump mentioned the words “sovereignty” or “sovereign” no less than twenty-one times. “President delivered a speech to his alt-right, anti-globalist base from the podium of the United Nations General Assembly,” warned David Rothkopf, a visiting professor of international relations at Columbia University. What Trump failed to deliver was any remark whatsoever on the gravest external threat of all to American sovereignty: Russia’s interference in the 2016 election.

But if Russia’s interference in the election poses the gravest external threat to our nation and all it stands for, then it’s Trump who poses the gravest threat domestically and existentially—though even many of Trump’s critics miss the deepest menace of his presidency. Trump is neither a modern liberal nor a conservative, but that is not to say he’s a blank slate ideologically. Rather, he is a true reactionary who would turn back the clock to an era of xenophobic nationalism, a vision shared by the most backward-looking of Americans, the neo-Nazis and the white supremacists. Like Trump, these reactionaries yearn for a return to an America dominated by white men and guided by a narrow conception of traditional culture, an America insulated from the world by tariff walls, restrictive immigration quotas, and isolationist policies. “We are determined to take our country back,” announced David Duke from the far-right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. “We are going to fulfill the promises of Donald Trump. That’s what we believed in. That’s why we voted for Donald Trump.”

At one point in time, extreme nationalism functioned as a foundation for building strong nation states across the world, but it cannot represent the future of the United States—not in our modern day. By the early twentieth century, unchecked insular nationalism had culminated in a worldwide depression, two catastrophic world wars, the collapse of multiple democracies, and the rise of dictatorships around the globe. In recognition of these tragedies, much of the world has moved toward the only viable future: one of gender and racial equality, global cooperation, free trade, common democratic values, and a united approach to fighting the catastrophic climate change that threatens human civilization. The number of worldwide democracies has soared—from just twelve in 1942 to more than one hundred by the end of the twentieth century—but democracy remains imperiled across the globe, endangered by the same reactionary forces that Trump now has unleashed in America.

Trump’s reactionary worldview is best symbolized by his commitment to erecting a wall along America’s southern borders—a throwback to the unsustainable walled cities of medieval times. People could not prosper or thrive in these conditions. They suffered due to polluted water, shortages of food and consumer goods, crumbling habitation, and deficient sanitation. They were ravaged by diseases, like smallpox, dysentery, and the catastrophic Black Death. For a short while, the walled cities may have provided protections, but as technology advanced—as it always does and will continue to do—the walls became useless for defense.

This vision of a walled-off nation is not populist, but profoundly elitist. It reeks of the fortress mentality of privileged Americans who, like Trump, have retreated into the shelter of gated enclaves—guarded versions of medieval castles. He hides out in Trump Tower, away from the very people who flock to his rallies. In the words of renowned late scholar Umberto Eco, “Such postmodern neomedieval Manhattan new castles as the Citicorp Center and Trump Tower [are] curious instances of a new feudalism, with their courts open to peasants and merchants and the well-protected high-level apartments reserved for lords.” In 1984, Trump even planned to build a literal “Trump Castle” in Manhattan, complete with battlements, a moat, and a drawbridge. The project’s architect said that the castle’s medieval-style defenses were “very Trumpish.” Potential tenants could buy into a castle residence for $1.5 million, but Trump’s dream project collapsed when the owners of the proposed site declined to participate.

Even if the president’s backers cannot access the upper reaches of Trump Tower, they can still hold out hope that his walled-off America will protect their threatened livelihoods and culture. “Protection,” Trump proclaimed in his inaugural address, with literal and figurative connotation, “will lead to great prosperity and strength.” Sadly, for the people who have bought into it as well as for those who have not, it’s an unfathomable vision. Trump cannot wall off the nation from the findings of science, from invasive pathogens like the Zika virus, or from the ravages of monster storms, chronic floods, runaway wildfires, and killer droughts. He cannot block out the technological advances that have rendered coal mines and old-style smokestack industries largely obsolete in the United States. He cannot insulate America from the global economy, or from progress that’s well underway. And Trump cannot re-create a culturally uniform, white “pioneer stock” America through any amount of immigration restrictions or mass deportations; already, the demographic die is cast for a pluralist future.

Trump’s reactionary impulse is inevitably authoritarian, and it explains much of his overreach as president. Reactionism cannot withstand a democratic process broadly open to all voters in an increasingly pluralistic nation; it cannot withstand challenges to autocratic control over the flow of information and ideas. Hence the obsession with alleged voter fraud, the free press, and internal “leakers.” The future of America cannot, will not, be that of a walled-in nation, either literally or figuratively.

CHAPTER 1 (#u02e1622b-9977-5a71-a43a-1d59df368cff)

High Crimes and Misdemeanors (#u02e1622b-9977-5a71-a43a-1d59df368cff)

____________

The President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.

—Article II, Section 4, Constitution of the United States of America

IMPEACHMENT 101

The first thing you need to know is how impeachment works: The impeachment and removal of a president begins under the Constitution in the United States House of Representatives. An impeachment typically begins with an investigation by the Judiciary Committee. If the committee decides to investigate, it may then by majority vote recommend articles of impeachment to the full House. Members then vote up or down on each article. The House may also proceed with impeachment regardless of the Committee’s recommendations. If a majority of the House ratifies one or more articles of impeachment, the case against the president proceeds to a trial by the Senate, presided over by the chief justice of the Supreme Court. A special prosecutor, a representative from either party, or even members of the public can request an investigation, although the Committee or the full House must agree to proceed with the inquiry.

At trial, the Senate acts as both jury and judge, with the power to subpoena witnesses, issue contempt rulings, dismiss charges, set trial procedures, and overturn rulings of the chief justice. Prosecutors appointed by the House present their case to the Senate, and the accused makes his choice of counsel for the defense. There is no requirement that the accused must appear in his own defense. At the end of the trial, the Senate has the power to convict and remove the president by a two-thirds vote of those present.

A president cannot pardon himself from impeachment, and if ousted by the Senate, he immediately sheds the protection of presidential immunity and becomes subject to arrest, prosecution, trial, and conviction under state or federal criminal law. By a separate vote, the Senate can bar a convicted president from holding any future federal office. Otherwise, an impeached president, if constitutionally eligible, could run again for White House. A president can run again if he was not elected twice or if elected once he did not serve for more than two years as an unelected president.

Decisions on whether to impeach a president turn on the wisdom of Congress and do not require proof of a specific indictable crime under either federal or state law. The verdict of the House and Senate is final. There is no right of appeal or judicial review of their decisions.

Impeachment covers not just presidents, but other federal officials, notably judges appointed for life. Since America’s founding, the House has impeached two presidents and fifteen judges. The Senate acquitted both presidents. It convicted eight of the judges.

AMERICA’S FOUNDERS STRUGGLE WITH IMPEACHMENT

After what George Washington called the “standing miracle” of his victory over British arms, the general retired to his Mount Vernon plantation. Bouts of smallpox, tuberculosis, malaria, and dysentery and years of tense warfare had racked his body, leaving him prey to debilitating aches and fevers and a “rheumatic complaint” so severe at times that he was “hardly able to raise my hand to my head, or turn myself in bed.” Yet in 1787, Washington donned his best breeches and frock coat, powdered his hair, and pushed his body to serve his country again: this time as the indispensable president of a constitutional convention in the sweltering Philadelphia summer.

In the span of just over a hundred days, the delegates created a radically new frame of government powerful enough to protect and preserve their fledging republic, but one with enough checks and balances to safeguard against the tyranny that Americans had endured under British rule. These learned but pragmatic politicians adhered to the later warning of John Adams that: “Men are not only ambitious, but their ambition is unbounded: they are not only avaricious, but their avarice is insatiable.” Therefore, “it is necessary to place checks upon them all.”

The framers adopted impeachment as a necessary check against tyranny. “Shall any man be above justice?” asked the influential Virginia delegate George Mason. He warned that it is the president “who can commit the most extensive injustice.”

Although they agreed on the need for impeachment, the delegates struggled with defining the grounds for indicting and removing federal officials. During the convention debates, to specify the criteria for removing a president, delegates used such disparate terms as “great crimes,” “malpractice or neglect of duty,” “corruption,” “incapacity,” “negligence,” and “maladministration.” They finally cast their vote for “high crimes and misdemeanors against the state,” then dropped the “state” qualifier, which both broadened and obfuscated the meaning of the impeachment.

POLITICS WITHOUT CRIME

In the election of 1800, after one of the nastiest campaigns in U.S. history, the nation experienced its first political upheaval when the Democratic-Republican Thomas Jefferson defeated the Federalist incumbent president John Adams. Federalists attacked Jefferson for his alleged atheism, radicalism, and lack of moral standards. One propagandist warned that with Jefferson as president, “murder, robbery, rape, adultery, and incest will be openly taught and practiced, the air will be rent with the cries of the distressed, the soil will be soaked with blood, and the nation black with crimes.”

The Jeffersonians fought back, charging Adams with scheming to extinguish the republic by marrying one of his sons to the daughter of the King of England and reestablishing British rule over America.

During this interregnum, John Adams pushed through the Judiciary Act of 1801, infuriating the victorious opponents. The act created sixteen new circuit court judgeships and reduced the size of the Supreme Court from six to five, thereby depriving Jefferson of an appointment. In the nineteen waning days of his presidency, Adams appointed so-called Midnight Judges to these new circuit court positions. When Oliver Ellsworth, the chief justice of the Supreme Court and an Adams loyalist, conveniently retired, Adams was quick to appoint the staunch Federalist John Marshall as his replacement. Marshall served as chief justice for more than thirty years.

Jefferson and his new partisan majority in Congress repealed the Judiciary Act and turned to impeachment for rectifying what they decried as the Federalists’ packing of the courts. They carefully picked as their first target the elderly Federalist district court judge John Pickering, whose advanced dementia and alcoholism led to erratic and sometimes bizarre behavior on the bench. The impeachment of one of many federal trial judges may not amount to very much, but Jefferson and his allies in Congress targeted Pickering as part of a larger plan: to breach the separation of powers and place the constitutionally independent judiciary under the heel of the president and his party. Ironically, it was Thomas Jefferson, who famously had written in his “Notes on the State of Virginia” that concentration of power “in the same hands is precisely the definition of despotic government,” who led this assault on the separation of powers.

Jefferson as party leader set in motion the House’s proceedings against Pickering by transmitting to Congress “letters and affidavits exhibiting matter of complaint against John Pickering, district judge of New Hampshire, which is not within executive cognizance.” Eventually, Jefferson’s loyalists in the House drafted four dense articles of impeachment. None charged a specific violation of law, instead merely citing Pickering’s poor judgment, intoxication, and rants from the bench as evidence that he lacked the “essential qualities in the character of a judge.”

The Senate convicted Pickering in a straight party vote, making him the first federal official removed from office under Article II, Section 4 of the Constitution. Senator William Giles of Virginia, the Jeffersonian leader in the Senate, said bluntly: “We want your offices, for the purpose of giving them to men who will fill them better.” Lynn W. Turner, the preeminent historian of the Pickering impeachment, wrote, “By confusing insanity with criminal misbehavior they [the Jeffersonians] also wiped out the line between good administration and politics and made any word or deed which a political majority might think objectionable the excuse for impeachment and removal from office.”

Emboldened by Pickering’s successful conviction, the Jeffersonians next targeted the United States Supreme Court by impeaching Federalist justice Samuel Chase. In 1804, the House voted along party lines to charge Chase with eight articles of impeachment; seven turned on his allegedly unjust and partisan judicial conduct and rulings. The final article cited “intemperate and inflammatory” and “indecent and unbecoming” remarks that Chase made while charging a Baltimore grand jury. None charged him with an indictable crime. The Senate acquitted Chase on all articles, which ended Jefferson’s war on the judiciary but did nothing to clarify the grounds for an impeachable offense or stop similar maneuvers in the future.

In his famed 1833 Commentaries, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story reflected on the constitutional history of impeachment and the examples of Pickering and Chase. Impeachment, he concluded is “of a political character” and reaches beyond crimes to “gross neglect, or usurpation, or habitual disregard of the public interests, in the discharge of the duties of political office. These are so various in their character, and so indefinable in their actual involutions, that it is almost impossible to provide systematically for them by positive law.”

The first impeachment of an American president, Andrew Johnson in 1868, would show just how prophetic Story’s words proved to be. Johnson’s impeachment raises three major issues that are still lively and controversial today: 1. What are the grounds for impeachment, 2. What is the scope of presidential authority and, 3. What is the president’s responsibility to obey the law?

THE MOST ACCIDENTAL OF PRESIDENTS

Like Donald Trump, hardly anyone expected Andrew Johnson to become president of the United States. If Trump seemed destined for stardom in business, young Andrew Johnson, born into poverty and apprenticed to a tailor at the age of ten, seemed destined to sew buttons and cut cloth for the rest of his days. What Johnson lacked in sophistication he compensated for in ambition, grit, and bravado. With help from his wife and customers at his shop, he first learned to read and eventually became a compelling speaker who had a say-anything style that confounded the conventional politicians of his time.

Johnson scratched his way up the sand hill of Tennessee politics as a Democrat in the early and middle years of the nineteenth century. He eventually became a United States senator in 1857. Johnson campaigned as the champion of the common people of America, who he said the political elites of his time had scorned and ignored.

Four years later, Johnson’s political career seemed over when the nation plunged into civil war. Seven southern states, threatened by the election of Republican president Abraham Lincoln on a platform opposed to the expansion of slavery, seceded from the Union before his inauguration. The Civil War began when Confederate batteries fired on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, and in June, Tennessee seceded, becoming the last of the eleven states of the Confederacy.

As a slaveholder who upheld the sanctity of the federal union, Johnson was the maverick of his time, and he was the only senator in a seceding state who refused to resign his seat and join the Confederacy. Although Union predictions of a quick victory proved false and the war would grind on for four bloody years, Johnson’s exile was short-lived. In February 1862, Union troops captured Nashville, Tennessee, making it the first Confederate state capital restored to the Union. Republican president Abraham Lincoln rewarded the loyal “war Democrat” Andrew Johnson by appointing him governor of Tennessee.

Two years later, Lincoln dumped his vice president, Hannibal Hamlin, and put his prized Democrat, Andrew Johnson, on his reelection ticket in a show of national unity. In his second inaugural address, Lincoln spoke of how the great and bloody war was a divine retribution for slavery, visited upon a guilty people both north and south. If the bloody war “continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk,” he declared, “and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said, ‘the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.’ ” His new vice president, Andrew Johnson, listened, but failed to comprehend the profound implications of Lincoln’s words.

THE WORST FATE THAT COULD BEFALL HIM

On April 15, 1865, just over a month after his inauguration, Lincoln died after the first presidential assassination in American history, and Johnson became the most accidental of presidents. In the wake of Lincoln’s death, Johnson showed a humility of the moment never seen in Donald Trump, commenting, “I feel incompetent to perform duties so important and responsible as those which have been so unexpectedly thrown upon me.” But Johnson’s humility did not last. His more enduring character traits inclined him to stubbornness, hasty action, disdain for cautious advice, and ill-tempered retorts against critics.

Johnson loved the Union but not the black people it had liberated from slavery. Although later in life a moderately wealthy slaveholder, Johnson rose from the lower ranks of white society, what some at the time called “mudsills,” the humble white farmers, laborers, tradesmen, and mechanics that, like Trump, he had championed in his political campaigns. He saw mudsills as threatened both by aristocrats from above and aspiring black people from below. At an outdoor rally, he told a crowd of cheering white men that he was their Moses who would lead “the emancipation of the white man” from their slavery under postwar Reconstruction. Johnson, declared the former slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass euphemistically, is “no friend of our race.”

Johnson was an odd man in his time. He was an apostate Democrat assuming the incumbency of a Republican president. He lacked allies in either party and prided himself as an outsider untethered to a capital city that he called “12 square miles bordered by reality.” By opposing efforts to reconstruct the nation and integrate newly freed slaves into American life, Johnson quickly fell afoul of a Congress controlled by Republicans with southern states still in limbo. He pardoned from the consequences of rebellion thousands of wealthy planters, some of whom with their wives had wined and dined him in Washington. With his humble roots and his penchant for spouting populism but privileging the rich, Johnson foreshadowed Trump.

Johnson pushed to restore southern states swiftly to the Union with no controls on race relations. He lambasted the “Radical Congress” for giving blacks privileges “torn from white men.” In a comment eerily similar to Trump’s denigration of a “so-called judge,” Johnson decried Congress as “a body called or which assumes to be the Congress of the United States.” He proclaimed to be protecting America, not from ex-Confederates, but from radical Republicans and their Negro allies. He forced Congress to override his vetoes on legislation aimed at protecting black rights and safety in the South and exploited his powers as president to evade and obstruct the enforcement of these laws.

Johnson’s conduct had tragic consequences for black people in the South. He restored to power, political and economic, much of the old slaveholding elite, who proceeded to keep their former slaves poor, controlled, and powerless. He forced his successor president and Congress to essentially begin anew much of the process of Reconstruction. Ultimately Reconstruction failed. The South remained mired in poverty, and the white supremacists who regained full control of southern governments imposed on African Americans the Jim Crow system of segregation and discrimination that endured for nearly a century. The failure of Reconstruction, “to a large degree,” wrote the historian Michael Les Benedict, “could be blamed alone on President Johnson’s abuse of his discretionary powers.”

In 1867, murmurings of impeachment began to circulate among exasperated, radical Republicans in Congress. In March, they had enacted over Johnson’s veto the Tenure of Office Act, a law that cut into his powers by prohibiting the president from replacing without consent of the Senate any federal official who had previously won Senate approval. To bait an impeachment trap, Congress inserted a clause that said any violation constituted a “high crime and misdemeanor.” And then, they waited.

JOHNSON STANDS HIS GROUND

Johnson was at the defining moment of his presidency. His response to Congress’s challenge would decide his own fate as president, with profound implications for every successor in the White House. He could battle Congress and risk impeachment or withdraw from the fray and count down passively the final days of his presidency. Or he could change his ways and reach an accord with the Reconstruction Congress.

Johnson stayed true to his notoriously pugnacious character and chose to fight. He taunted Congress by deliberately violating the Tenure of Office Act. “I have been advised by every member of my Cabinet that the entire Tenure-of-Office Act is unconstitutional,” he later said.