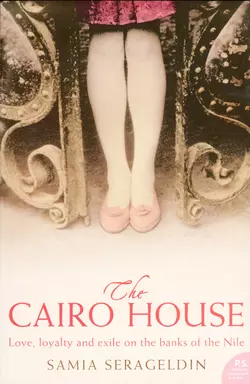

The Cairo House

Samia Serageldin

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 542.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A beguiling, entrancing novel that tells the story of a prominent Egyptian family’s struggle to survive the turmoil of post-World War II Cairo.Gigi grew up in a wonderful house in Cairo, a house that was home to a large, extended family. The men of the house were involved in politics and business, cotton and trading, and the women visited and gossiped, shopped and arranged marriages and other family matters. The house was always open to visitors, political associates, family: the traditional Egyptian hospitality mixed easily with a cosmopolitan style. It was an opulent world that seemed unchangeable.But the pashas’ time was ending. Many were forced into exile, and for those who remained there was an uneasy mix of new expectations and old traditions. Gigi, a modern woman from a patrician background, faced the conflicts between a traditional marriage and the loss of a family, between exile and the need to create a new life while striving to stay in touch with her roots.Samia Serageldin’s first novel is a brilliant, haunting and fascinating story of a woman, a family and a culture in transition.