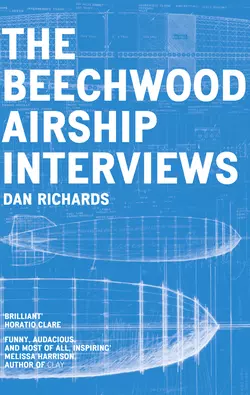

The Beechwood Airship Interviews

Dan Richards

A journey into the headspaces and workplaces of some of Britain’s most unique artists, from the co-author of the critically acclaimed Holloway.Bill Drummond. Richard Lawrence. Stanley Donwood. Jenny Saville. David Nash. Manic Street Preachers. Dame Judi Dench. Cally Callomon. Sheryl Garratt. Vaughan Oliver. Jane Bown. Steve Gullick. Stewart Lee. The Butcher of Common Sense. Robert Macfarlane.Artists. Writers. Photographers. Musicians. A comedian. An actor. A printer. An airship.The people interviewed in this book come from all corners of Britain’s cultural landscape but are united in their commitment to their craft.At the beginning of this extraordinary memoir, Dan Richards impulsively decides to build an airship in his art school bar, an act of opposition which leads him to meet and interview some of Britain’s most extraordinary artists, craftsmen and technicians in the spaces and environments in which they work.His search for what it is that compels both him and them to create becomes a profound examination of what it is to be an artist in 21st Century Britain, and an inspiring testament to the importance of making art for art’s sake.

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_e9067803-7740-535d-a3c2-b076b52ab5f0)

The Friday Project

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by The Friday Project in 2015

Copyright © Dan Richards 2015

Cover Layout Design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover by Stanley Donwood

Dan Richards asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008105211

Ebook Edition © March 2015 ISBN: 9780008105228

Version: 2015-09-11

For Jo

Many are prepared to suffer for their art. Few are prepared to learn to draw.

– Simon Munnery

CONTENTS

Cover (#u31052cc1-a4ee-5dca-9cb6-3c52ae944a82)

Title Page (#u2a405105-e0b5-5b87-b7d5-b583441d74e0)

Copyright (#ud56b7ed8-79df-5203-aff9-419748bf5f90)

Dedication (#u96ece47d-01fd-5f8f-ad68-d891f6f0de57)

Epigraph (#u9fa4e178-c387-5539-bc66-fa12d68863b5)

INTRODUCTION/LIMINAL SPACE (#ude592d8d-4dbd-585e-8021-975138d50fa5)

BILL DRUMMOND (#u4856c1e6-45b3-5a9e-a852-52ce08a378e8)

RICHARD LAWRENCE (#u25819e26-a8db-586c-9084-417a8ca85463)

STANLEY DONWOOD (#ubdef566d-7d43-5f10-b2dc-e8ec0ceabeb0)

JENNY SAVILLE (#ufc3aa49b-53da-5e1b-b3a9-9eb77f146b66)

DAVID NASH (#litres_trial_promo)

MANIC STREET PREACHERS (#litres_trial_promo)

DAME JUDI DENCH (#litres_trial_promo)

CALLY CALLOMON (#litres_trial_promo)

SHERYL GARRATT (#litres_trial_promo)

VAUGHAN OLIVER (#litres_trial_promo)

JANE BOWN (#litres_trial_promo)

STEVE GULLICK (#litres_trial_promo)

STEWART LEE (#litres_trial_promo)

THE BUTCHER OF COMMON SENSE (#litres_trial_promo)

ROBERT MACFARLANE (#litres_trial_promo)

EPILOGUE (#litres_trial_promo)

Footnotes (#litres_trial_promo)

The Butcher of Common Sense Footnotes (#litres_trial_promo)

Thanks (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Discography (#litres_trial_promo)

List of Illustrations (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Dan Richards (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

LIMINAL SPACE (#ulink_f10ba78a-0231-5d48-844b-acbde50b7213)

In the summer of 2006 I moved to Norwich from my family home in Bristol to begin a Creative Writing MA at the Art School.

It was a year since I’d graduated from an English Literature and Philosophy BA at the University of East Anglia. I had spent the intervening months working in a bookshop staffed entirely by graduates sheltering from an indifferent world, presided over by a weirdly ageless Brylcreemed man who, when he wasn’t smoking on the roof – arcing his dog-ends languidly into the yard of the adjacent church – would lock himself in his attic office or materialise at your elbow to relate how his father nursed the captive Rudolf Hess.

The shop had a very limited selection of Art books and an even meaner smattering of Photography and Transport.* (#litres_trial_promo) There was no demand, we were told, and it was this message that we passed on to any customer who enquired, taking great pleasure in directing them up to the ‘better stocked, less expensive shop’ at the top of the road (‘where we would much prefer to work’).

I had no idea what I was doing at the shop but day after day I’d be there, going through the motions of retail. I’d reached an impasse. It was relatively easy work and brought in a small wage, which I’d eke out during the week so I could catch a train to the South Coast to see my girlfriend at weekends. Sometimes I’d get to Brighton and she’d be happy to see me. Sometimes not. Sometimes she’d say, ‘I’m not sure how I feel about you being here … turning up like this …’ and I’d freeze there on the doorstep; tired and punctured, foolish – as if I’d spoilt the most simple of tasks: just turn up and don’t be shit.

Life in Barcelona-on-Sea unravelled as a mess of well-meant gestures and hissed upset. I was sure we had it in us to be happy but we weren’t; we really weren’t.

This went on for months.

I’d think about us all the week while stickering 3 for 2s or directing people up the road, but in my head she smiled more and shouted less.

In retrospect I’d been sleepwalking through many things. She left fairly suddenly. She had indeed been unhappy for a long time. I received a postcard quoting Virginia Woolf’s suicide note as an unequivocal gesture of severance.

That was it.

I moved up to Norwich earlier than planned and drank a lot of gin on my own in a conservatory.

Then I got a cat.

Then I got a night job washing dishes in a pub.

I’d return home in the small hours covered in sink dross, drink more gin and complain to the cat about love.

It became clear that I needed direction, to begin something new, or I’d go mad, fill my sink-drossed smock with bricks and throw myself into a pond.

I threw myself into the art school instead.

• • • • •

In the weeks before term started, I began working in the Student Union bar – a large timber-beamed hall above the canteen – a building which put me in mind of St Pancras Station, all mustard brickwork, corkscrew chimneys and gothic arches; an eccentric building which seemed to embody the idea of an art school.

Accessed up a spiral staircase in a turret tucked away, the bar had a welcoming, secret feel and it was always great to see freshers double-take on first discovery, as I had – caught out by the size of the space, drawn in by the warmth towards the silhouetted people clustered around long tables and stood at the bar while candle shadows flickered the roof joists high above.

Like a massive womb … with Jägermeister.

Hulking cast-iron radiators hugged the walls and creaked, their heat rippling the curtains. The hall was always warm, even on the dark mornings as I swept and served coffee to the few brave souls awake – or yet to go to sleep.

On quiet evenings, the staff would play Scrabble or perch at the bar and talk, and it was on one of these slow nights that Rob, the manager, and I hit upon the idea of an airship.

We were staring into space, I remember; talking about the bar.

At this point the bar was one of the few places in the school where students could exhibit their work, and the walls, ledges and large windowsills were crammed with sculptures and paintings. A huge canvas by Bill Drummond hung on one side of the hall which said GET YOUR HAIR CUT, one of a series of works the artist had lent to Rob to display in the bar. I think Rob and I were talking about this as we stared up into the eaves, discussing GET YOUR HAIR CUT, the student art on show, the roof – our conversation spinning off at intervals but always arcing back to large student work and the roof space.

That morning I had been exploring Norwich and discovered the brass plaques on the doors of City Hall which depict the history and trades of the town. One showed an engineer working with a propeller – a reference to the firm Boulton & Paul Ltd, a general manufacturing firm which built aircraft and airships among other things.* (#litres_trial_promo)

Talking to the art school caretakers about the doors later that week I was told how Boulton & Paul Ltd had won the contract to construct the frame of the fateful R101 airship in the 1920s, then the largest aircraft ever built.* (#litres_trial_promo) One old boy recalled being held aloft as the ship flew over Norwich on a test flight.

‘The whole city stopped to watch it circle and pass. Everyone was out in the streets.’* (#litres_trial_promo)

Maybe R101 was circling and passing through my mind that night because the conversation about GET YOUR HAIR CUT, student work, and the roof came to rest on me, suggesting the construction of a large-scale airship above the bar. That would be brilliant, we agreed; and then went back to staring into space.

• • • • •

A week passed. I knew Rob had probably forgotten about our conversation and I still had every opportunity to forget it too and walk away, but the seed was sown and the space was there, waiting. I couldn’t look up any more without seeing the negative space of a large, ominous airship hanging there, goading me.

• • • • •

A month into the winter term I had drawn and researched to a point where I’d some idea of the airship’s size. I wanted the balloon to loom in a big room and as such it would have to be large. Six metres long, perhaps; over a metre in diameter. Also, it would have to be light so as to hang from the trusses without causing damage and, most importantly, look right. If weighty and over-engineered it would look wrong, I knew – it had to appear to float. Wood and paper, then – flexible, strong woods covered in paper like a kite.

However, it became clear that there wasn’t the space for me to build it in the art school workshops. I remember I sought out a technician and we paced the airship out; too big. Not that there seemed a surfeit of students making massive wooden things; not that there seemed much being made at all – the wood workshops seemed principally employed to make canvas stretchers and the main wood of choice appeared to be ‘ply’.

My rough notes about the ‘springing/laminate potential of beech and birch’ were met with polite concern. I was pointed towards the birch ply and chipboard.

‘That’s not really wood, though, is it?’ I asked the technician.

I think he took that rather hard.

I decided to let it lie.

Within a week it wasn’t the woodwork which concerned me as much as the people coming out of it to ask why I, a student on a two-year part-time writing MA, wanted to build things at all.

• • • • •

I am writing this introduction a couple of years after the events I’m describing and it’s strange to think now but my idea of an art school can’t really exist any more. The new fee system introduced after my time in Norwich has brought an end to the idea of studying with an open mind ‘just to see what happens’. I don’t think you can really do that if you’re paying £30,000.

The notion of value has shifted and the vocational is king once more. To pay out so much ‘just to see what happens’ seems decadent; the fees will surely cost out those unsure of what they want to become, or looking for an adventure.

Jarvis Cocker expressed the idea well:

‘As much as I wanted to study something, I went to Saint Martin’s because I just wanted to get out of Sheffield. I just looked at the colleges and it said, “This one is on Charing Cross Road”, so I thought, “Great, three years in Soho. Summat’s going to happen.” And it did.’* (#litres_trial_promo)

To arrive in a space and be inspired to make art by its fabric and atmosphere – if I’d been asked what my ideal of an art school was before I arrived in Norwich, that would have been close … but maybe we’ve moved into a post-impulsive airship epoch.

Today, all government funding cut, I note the school has closed down my course and moved towards a more logical, verifiably employable roster of subjects – the abstruse hinterlands of Fine Art and Sculpture squeezed in favour of the more honest fare of Fashion, Graphic Design and Animation; a white sea of Macs sweeping all before it.

But let’s return to the winter of 2006 and the wood workshop where I’m not going to work and look around. There are tools here. The ones on show are old and battered. The better ones are locked away, we’re told, because otherwise they’d walk. Security is a problem and the technician cannot be everywhere at once, so the available kit walks and the rest is kept hidden.

Paranoia permeates the space and I feel bad for the technician, who’s doubtless doing his best but he’s under pressure and having to take on responsibilities beyond his original remit. In this context it’s reasonable to suppose that writers on part-time MAs talking about ambitious zeppelin projects would be given short shrift. He has to be there. He’s put upon. He’s busy. I bet he had people in there ‘talking’ all the time. Time wasters, charlatans, and opportunists – out to nick the shiny G-clamps, light-fingered magpies with asymmetric haircuts. Bastards to a man!

Now, it’s all very well writing this down with hindsight and retrospect and all the other tools available after the event – indulging in a bit of the third person to suggest a distance between now and then, the school and me, the technician and me – but it’s important to say that I didn’t help my cause.

I don’t like confrontation. Hate it. I felt plywood wasn’t the way to go and should have stood my ground, but it was much easier to smile along and nod and agree we should order a load of it and then run away; it was the hiding for the next two years which proved tricky, especially since the wood workshop stood at the entrance to one of the main buildings at the school and I knew I’d upset a man with a large collection of hammers.* (#litres_trial_promo)

• • • • •

In early 2007 I travelled down to Henley-on-Thames to ask a pair of boat builders how best to construct an airship.

En route to London, the previous week, I’d spoken to my father at length about the project and he’d suggested that to question received wisdom, to experiment, fail and learn, was the point of a degree. Better to fail on your own terms than be led astray and compromise:

‘You know, you’ll spend ages building it out of the wrong stuff to please someone else, it’ll go wrong and you’ll end up smashing it up with an axe, or something …’ he pronounced near Heston Services, adding, ‘You’ve made your bed now anyway.’ * (#litres_trial_promo)

• • • • •

Colin Henwood and Richard Way know about wood and their knowledge is deep. At our first meeting we sat in the shed at the heart of their yard and talked around the airship – unpacking each possible solution, weighing the ways it could be done. This took quite some time since it turned out I had many options – different woods, fixings, joints, glues; each with their own character and peculiarities.

Their enthusiasm for the project, my doodled sketches and the mooted materials spilled out along tangents and into stories about craft.

At that first meeting, Richard spoke of his work with wood and boats, his tools and concerns, with a love and mesmeric intensity that affected me deeply and has subsequently shaped this book. He put the idea in motion that people who love what they do, are immersed and consumed by their work, are wont to speak about it with an engaging and infectious generosity. There was no cynicism when he spoke, just a simple clarity of thought, of process and labour, and this was to set a pattern for many subsequent exchanges I was to have; in fact it’s largely due to Richard’s enthusiasm and lucidity that I went out and sought those exchanges at all. I’d taken along a rudimentary Dictaphone to record our chat – and it was to be a chat, a casual meeting for which I’d made no notes other than rough drawings and annotations in my journal. I suppose I imagined I’d be there an hour or two. But two hours turned into four, and lunch, and as dusk fell we three were still talking. I didn’t want it to end, it was such a pleasure. When I got home I transcribed the tape and happily listened to the day over again.* (#litres_trial_promo) Below is a little of our conversation, beginning with Richard describing his daily routine:

‘I start at half past seven during the week and finish at six o’clock. I used to work much longer. My first experience of boat building was working at a time when there was much too much work and not enough people so we used to work through till ten o’clock at night or one o’clock in the morning and that went on month after month so I got very used to terribly long hours. You can’t do that when you get to my age, it just becomes too exhausting.’

What age were you when you started?

‘I was twenty-one. It was tiring but at that age you can do enormous amounts of work and still get up the following morning and do it again. Young people are always half out of control anyway, aren’t they? (Laughs)

I discovered shortly after I started that I much preferred using tools that had been used before. It wasn’t a conscious decision to begin with but … I can feel a lot through my hands. I’ve got a very delicate sense of feeling and just felt that new tools were very sharp, all their edges were very sharp, and I much preferred buying old tools that were quite worn but still very usable.

You always buy some things new because you want the full length of a long paring chisel, for example, but gradually I’ve swapped over all the ones I bought new for older ones I’ve found. It didn’t become an obsession, thankfully, but I decided that I liked knowing about tools, so I read a lot of books and I used to buy tools when job-lots came up at local auctions, and sometimes I’d get them from people I knew, so that meant I’d tools that reminded me of the man who owned them before. I’ll pick a tool up and think, “Ah, that’s Pat Wheeler’s – the old boy who lived in the village.” It brings a picture up in my mind which is rather fine and it’s nice to know that your tools have done other work, you know; generations of work.

At home in my workshop, I’ve tools that are centuries old – Georgian chisels, things like that, and they’re absolutely magnificent. I’ve got Georgian wooden planes, braces, and drills, extraordinary things …’

At this point Colin pointed ruefully to Richard’s toolbox – a blanket box on caster wheels – a hefty laden chest:

‘As you can see, Dicky hasn’t brought very many tools with him today …’

And as we laughed I became aware that the scope of my project was opening out, alive in the room, after so many months of being closed down. I was engaged with people who knew what they were doing. The spectral airship flew here too – more than that – buoyed by enthusiasm, it lived.

For the next few months, every chance I got, I travelled home to Bristol to build the ship of my imagination – 200 miles from the art school bar as the crow flew.

The body of an airship is a collection of variously sized hoops fixed together with cross braces – dirigibles generally have a keel like a boat, their skeleton frame distinguishing them from blimps, which are essentially bags that use gas pressure to maintain their shape.

To start with I set about making twenty hoops of various sizes – each as thin and strong as possible, each formed of three or four layers of beechwood. Beech has a fine grain which lends it a strength and flexibility suited for shaping and moulding – for this reason it is used a great deal in furniture making. I built up a laminate sandwich of wood/glue/wood/glue/wood around circular template formers, each a slightly different diameter – clamping each complaining lath length tight until it set, before adding the next.* (#litres_trial_promo) My first efforts were fairly awful but gradually I learnt what I was doing and the hoops began to take a more uniform, circular shape.

Successful rings were laid out on the floor like ripples; pear-shaped failures were taken outside and burnt.

While laminates dried in their jigs, I moved on to the nose and tail. Again, this was trial and error and the thought that it was all going to fall apart or bow (and then fall apart) was never far from my mind; but I was fathoming the beech and coming to respect its toughness. Once layered up and glued into shape it was steadfast. The material didn’t lie. When I botched I couldn’t blame the beech, which often called my bluff; refusing to be undone – wood and glue having become a sturdy third thing – hoop or half-uncoiled mess.

Four tailplanes were measured and marked on board, sawn up, sanded and slotted together – aerofoil ribs fixed at regular intervals looking beaky and svelte.

The dust was flying from the bandsaw blade, sketched revisions and tea stains filled my notebooks, and solvents daubed my boiler suit and stunk out my hair. At the end of each day, on the train journey home, I’d peel PVA from my hands.

The nose cone went together fairly quickly with a similarly slot-oriented approach to the fins – the profile of the front dome built up in segments to form a pointy jelly mould, a hollow cupola built around the smallest of my beech hoops; a card skinned nib.

An assembly frame was made on which to build the kit of bits. Thin stringer laths were cut to fix across the hoops and form the rigid frame – skeleton cigar … late nights listening to the radio, sugary tea and pencil shavings – ticking off the parts lists until early summer, when I packed up the airship like a pasta tangram into a Volvo Estate.* (#litres_trial_promo)

My MA, meanwhile, was going well. I was writing strictly relevant pieces for my course and moonlighting with zeppelins the rest of the time.* (#litres_trial_promo) As the first year finished and the long summer break between the first and second year stretched ahead, I was setting out my kit in the union bar, ready for the build.

Up went the frame with its central jig. On went the hoops, held by spars. Everything was clamped and cable-tied at this point since nothing was straight or square.

This part of the project was time-lapse filmed for posterity and the early footage shows me deploying tape measure and spirit level with enthusiasm. Lying on my back beneath the fuselage, head scratching, wandering off, wandering back with tea and a pencil, losing and hunting for the pencil, making notes, fiddling with string; like Buster Keaton … that was week one.

Week two saw the keels* (#litres_trial_promo) glued into place and the tail cone taking shape.

Week three was a bit of a write-off since I spent much of it undoing laths stuck into place under the influence of Guinness Export. The wrong place. Wonkily.

The nose was fixed in week four and the rest of the stringers followed. Because of the ship’s size, lath strips had to be seamed together at intervals with scarf joints, the two lengths cut with a taper and joined to form a continuous span. The scarfs were positioned at intervals so as not to create weak spots in the frame.

Week five, the tail fins went on; the central spars were cut and removed. The ship was carried off the stage and hung from its top keel for the first time, swinging slightly on its new jib. The team of bar staff who’d helped me lift and relocate it stood back.

‘Bit big, isn’t it?’ said Rob, looking warily up at the beams, and it was true; away from the stage and out in the room the airship did look massive.

‘Don’t worry,’ I reassured him, ‘I’ve done some maths and it only weighs as much as your legs.’

This seemed to settle him down.* (#litres_trial_promo)

• • • • •

All the time I was building the airship, especially in those final weeks, I was distracted. A couple of years later, Stewart Lee nailed the feeling:

‘You often don’t realise that you’re working on something in your head until it’s formed – you might have had something that you thought you were doing for fun or was just interesting to you but suddenly you realise that it’s all adding up into the shape of an idea.’

Now built – out of my head and over there, causing Rob to fret about the beams – I saw the airship as a manifest preoccupation.

It wasn’t just an airship built on a whim; it was a reaction – an elephant in the room – everything the art school seemed to be turning away from;* (#litres_trial_promo) a large, ambitious, crafted wooden piece of work which mirrored and celebrated the building around it, inspired by the ghosts of the city. I believed in the fabric of the bar and school and wished to celebrate that. The building was benign, inspiring and positive; it was the people at the top who concerned me.

Looking down the beech laths at the scarf joints, I felt the calm assurance of the materials and saw the influence of Richard and Colin in Henley-on-Thames and my father back in Bristol. The airship had put me in touch with them and articulated their knowledge better than words. The process was a language, lucid and succinct. It had an integrity.

I had faith in the wood and glue.

On 15 August 2007 I made the following note in my diary:

Today the bar paid for a set of ropes and pulleys and hired a scaffold tower.

I keep finding notes I’ve written about ‘People who know what they’re doing.’

I work here, in this room. The airship is site-specific.

The room is the space I respond to.

Does this happen to other people?* (#litres_trial_promo)

• • • • •

The scaffolding tower was assembled one weekend shortly before the start of the new school year. From the top it was clear that the eaves were a lot higher than they seemed from the bar far below. Three of us scaled the gantry to hang ropes and thread the pulleys and shortly afterwards the airship was winched into the air for the first time accompanied by a blast of ‘When the Levee Breaks’.* (#litres_trial_promo)

It was up.

From beneath, its lines merged and intercut the wood of the roof, putting me in mind of Orozco’s Mobile Matrix, a suspended whale skeleton,* (#litres_trial_promo) and as the concentric graphite circles drawn on those bones radiated out, overlapped and distorted, so the beams moved through the cage of beechwood above our heads now. The few of us there in the moments after it was raised walked up and down below as the airship swam.

Later I sat on the stage at the back of the hall and looked at it for an hour or two, watching it settle in the ropes. It was up; unpapered and naked for now but that could be addressed over time.

But the important thing, as Rob pointed out, was that the stage was now freed up for the pool table because, say what you like about arty kids in an arty bar, they loved their pool: ‘You know, given the choice between an arty airship and pool …’

Luckily such a nightmarish choice was never forced upon them.

The new term started and I went back to my MA, papering the airship on Sunday mornings with tissue paper donated by Habitat.* (#litres_trial_promo) I was helped in this task by Virginie Mermet, a brilliant French girl.* (#litres_trial_promo)

We’d arrive early and open all the windows to ventilate the stale ale air before making tea and lowering the airship down. Tissue was cut into strips and applied with aircraft dope – a varnish that tautened and strengthened the paper as it dried while giving us headaches and mild hallucinations.

During these mornings we’d talk about ideas of artists and space and listen to Klaus Nomi.* (#litres_trial_promo) Virginie was of the opinion that all artists create and respond to a space, be it site-specific sculpture like the airship or an environment attuned to making work. We spoke about photographs we’d seen of Francis Bacon’s studio and Roald Dahl’s shed, concepts of theatre and atmosphere; the idea that a resonance of creativity can remain in a building long after the people have gone and the function altered.

Kitchens, boat yards, studios, halls, sheds, rehearsal rooms, cellars, theatres, roofs, gardens, landscapes, vehicles – inspiring and facilitating artistry.

Some spaces must bear witness to a process while others stimulate it – become steeped in it. While some buildings evolve over decades into a perfect working environment, others are built for that purpose from scratch, others will be a compromise; some permanent, some fleeting, some known about and public, some private, even hidden.

That night as an experiment, I wrote a few pages about the broadcaster John Peel. Under the heading ATMOSPHERE, I recalled my second-year house at university; Thursday night, a large cold bedroom where the living room should have been. A desk, a set of shelves, a dicey gas fire, a bed, a wardrobe.

I’m sat at the desk in a thick jumper, illuminated by a balanced-arm lamp and the flicker of a radio set handed down from my mother – bought during the three-day weeks of the seventies because it could take batteries.

I’m listening to John Peel.

Thursday was not a pub night, Thursday was the night John broadcast his programme direct from his Stowmarket home, Peel Acres. Thursdays were sacrosanct. I remember taping Mono, The Black Keys and Four Tet sessions, listening with my finger hovering over the red button on the deck.

My diary of 13 May 2004 records that John played four session tracks by The Izzys and I enjoyed them very much. He opened the show with the greeting ‘Hello, brothers and sisters, and welcome to Peel Acres’ – very much the spirit behind those Thursdays; he was welcoming the audience into his home, where he sat playing tracks he thought we might like to hear – something new. Something by Jazzfinger or The Fall, say; the jet-wash of Part Chimp or The Izzys in session covering Richard and Linda Thompson.

Amazing to think how intimate it all felt – a man in his house in conversation with the world but broadcasting to you. A public service.

I remember the quiet of my room then, the crackle of the radio and the feeling of connectivity.

John Peel died in October 2004.* (#litres_trial_promo)

In 2008 I wrote to his wife, Sheila Ravenscroft:

‘Perhaps the most interesting spaces grow up and around the person working within them. The longer this project* (#litres_trial_promo) goes on, the more I think of John’s programmes from Peel Acres and recall the way the atmosphere of his studio seemed to percolate out into my room; the wonderful conversational way he had of speaking, how it fostered a world and set of associations that continue to inform what I’m writing today.’

• • • • •

In his book Waterlog, Roger Deakin describes a seemingly impossible swan dive made by a market-worker in the 1920s from the copper turret of the Norwich art school, over Soane’s St George’s Street Bridge and into the River Wensum.

A friend lent me the book towards the end of my degree and I raced through it, drinking up the words on water, wild swimming and landscape. A few minutes after discovering the Norwich nosedive passage, I was stood on the same bridge, text in hand, eyes skyward, trying to join the dots – turret, bridge, river. Copper, sky, Wensum – but the orbit did not fit.

I went back to my work on the airship, disbelieving – imagining the lad Goodson arcing, plunging head first and arrow-like – aiming at the water, his eyes brim-full of bridge.

I returned at lunchtime but the bridge was no thinner than before.

Did Roger Deakin stand here too? I wondered. Did he weigh the thing up?

Waterlog and Deakin’s subsequent book, Wildwood: A Journey Through Trees, suggested a course beyond art school.

Writing in 2010, his friend Robert Macfarlane described him as

‘a film-maker, environmentalist and author who is most famous for his trilogy of books about nature: Waterlog, Wildwood and Notes from Walnut Tree Farm. I say “nature”, but his work can perhaps best be understood as the convergence of three deeply English traditions of rural writing: that of dissent tending to civil disobedience (William Cobbett, Colin Ward), that of labour on the land (Thomas Bewick, John Stewart Collis), and that of the gentle countryman or the country gentleman, of writer as watcher and phrenologist (Gilbert White, Ronald Blythe).’* (#litres_trial_promo)

I had a lot of questions, had gone off piste with my MA to fill gaps in my heuristic knowledge and in so doing become convinced that something was amiss and the answers lay elsewhere, in the heads and hands of people at work.

Roger Deakin walked out to meet the people who knew – who swam, worked wood, dwelt and engaged with the land. Meeting with people in the spaces where they worked and lived, he found communion and kinship. Perhaps I, in light of the Beechwood Airship, could do the same and find some resolution … because the postmodern doublethink of the art school seemed a very lonely thing – a vacuum occasioned to funnel and mould the kids in a system where talk of aesthetic judgement is muted and neutered, shrugged off as subjective.

Such a cheap trick! A spiteful closing down of the cosmos and, I couldn’t help but think now, having clashed against the axioms of the institution, that their dogma was self-serving and unfit to underpin a job of work in the world beyond their walls.

I knew of graduates turned out as graphic designers with almost no knowledge of its history – the roll-call: Brody, Beck, Oliver, Saville, Kare and Scher passing without a flicker – set up to be a caricature with no depth to their knowledge beyond a syllabus which ticked the school’s boxes – eggshell graduates who’d only been pressed top down.

But then, perhaps this does the tutors a disservice, perhaps it wasn’t their fault – maybe they were under pressure to deliver a certain sort of course – perhaps the onus should be on the student to broaden their knowledge. Shouldn’t a degree be all-consuming? The past and present insatiably mined out, the future dreamt, the vocation so pressing that each new contextual source is gorged? But I knew from my own encounters that students were being dissuaded from going too far away from their prescribed course remit. Peregrination was not encouraged, cross-course collaboration dissuaded – at an art school! Surely that was wrong or was I being unreasonable?

No. You need more. You need enough rope to either hang yourself or create something great. And sometimes you need to get out on the road and discover it, physically seek and experience it for yourself – whatever that is.

Take risks. Get your hands dirty.

Bill Drummond’s totemic GET YOUR HAIR CUT and the MAKE SOUP that replaced it seemed a good place to start.

Where did he work? I wondered.

The final weeks of art school found me serving rowdy intemperance to student types on weeknights while Sundays passed in quiet concentration, Virginie and I lying side by side on the floorboards of the SU bar: papering the airship, strung out on psychotropic varnish fumes, listening to Klaus Nomi.

BILL DRUMMOND (1953– ) is a Scottish artist, musician and writer who came to prominence in the 1980s with his band The KLF. He achieved notoriety after burning one million pounds in cash as part of his art project the K Foundation. He is the author of several books and is the founder of countless art, music and media projects as well as the writer of two solo albums.

BILL DRUMMOND (#ulink_751c92dc-26b3-5f93-947d-94ec88ecf8ea)

St Benedicts Street, Norwich

Summer 2007

I’m building my airship in the Student Union; a month to go before the autumn term and the hall is empty. It’s early and brilliant sunlight pours down from the cinquefoil windows above me, flooding the low stage where I work.

I enjoy being here out of hours. I have the run of the building from as early until as late as I like.

Most of the student art and canvases have been stored over the summer – to be hung up again once the bar reopens – so the white walls are bare except for one large red and yellow canvas which looms to my left as I look down the room: MAKE SOUP.* (#litres_trial_promo)

I like MAKE SOUP. It greets me every morning with bright clarity and purpose. The framed text beneath it reads:

NOTICE

Take a map of the British Isles. Draw a straight line diagonally across the map so that it cuts through Belfast and Nottingham. If your home is on this line, contact soupline@penkilnburn.com Arrangements will be made for Bill Drummond to visit and make one vat of soup for you, your family, and your close friends.

I appreciate the simplicity and generosity behind this venture. I like soup, for one, but also I like the sense of quest, the bold colours, the aesthetic of the large stark letters − four and four, MAKE SOUP – the fact Bill will rock up and physically make you literal soup with his actual hands.

I look on Bill’s Penkiln Burn website and find that there are many more canvases of the same size and style − PREPARE TO DIE, SILENCE, DRAW A LINE, 40 BUNCHES OF DAFFODILS, STAY − each with an attendant story and aim.

I ponder what a BLOODY GREAT AIRSHIP canvas would look like; three words, one above the other. I sketch it in my notebook.

• • • • •

March 2009

Bill’s workshop is a grey unit with a roll-shutter front, solid and anonymous on a ring road industrial estate … outside Norwich.* (#litres_trial_promo) As the shutter rises it reveals a stacked interior. I follow him into the space, stepping over piles of books and magazines, around walls of filing cabinets and heaped boxes into a clearing with a large canvas suspended upside down on a stretch of bare white wall −

. White on red. Bill rummages in a cupboard and emerges with a handful of bungee leads, picks the canvas up and makes his way back out to the Land Rover, before climbing onto the substantial roof rack to secure it there. I ask what happens to his older, redundant signs; Bill says he paints over them.

Rather than the portentous figure I’d been expecting, Bill seems a quiet, thoughtful man – far more tolerant and humorous than I’d imagined. On the drive back into town I think over the disparity between the Bill with the reputation for dark shenanigans that I’d read about in preparation for this meeting and Bill the enthusiastic instigator of spontaneous choir The17 because it’s the latter who’s sat beside me now, imagining aloud waking up tomorrow to find all recorded music had disappeared.

• • • • •

Later that day − Norwich Arts Centre

A dark hall. Set up on a stage at one end is The17 canvas collected this morning. On the floor down the middle of the room runs a white line, bisecting the eighty or so chairs on which people are starting to sit, filing into the gloom from the light outside. Shuffling to a seat while their eyes adjust.

Between the seats and the stage is a table.

On the table sit a laptop and an Anglepoise lamp. The lamp is the only light in the room and the room − once a church − is large, with a high black vault and pillars that mark out the nave and frame the stage and table.

More chairs fill, more shuffling, low whispers.

Bill appears and walks to the front to a scattered applause and sits down to face the audience.

‘Hello,’ he says, ‘my name is Bill Drummond and you are The17.’

Thereafter the audience, myself included, are told the story of The17, how it grew from the sounds in Bill’s head as a child and his lifelong love of choral music; how Bill tried to fight the music, which welled while he drove his Land Rover, tried to ignore it, but how he found it swirled and coalesced with other ideas he was having about the way music in the twentieth century − recorded, manufactured, sold and now ubiquitous − had lost touch with time, place, event and performance … how he’d sought to write these feelings out in under a hundred words; how he got it down to ninety:

Bill sells us the idea of The17, seduces the room. He sits in his circle of lamplight before the red canvas and reads out ALL RECORDED MUSIC and his sonorous Scots tones reverberate around the building, then he moves to another score, IMAGINE, and begins to form us into a choir − no previous musical experience necessary − to create a new music. Year zero now.

I can’t tell you much of what happened next because it would spoil the inherent mystery and magic of The17 as a uniquely immersive happening, but it’s enough to say that the choir, led by Bill, made sounds that swelled and filled the space, more moving and beautiful than I had ever expected and when we filed out of the building, blinking in the light, we were all grinning and buoyant and wanted to do it again.

• • • • •

Later still that day − Rob’s front room* (#litres_trial_promo)

There is only one chair in the room where we later convene to talk. Bill sits on it. I sit on the floor. At this angle he appears even taller than he is – which is very tall.

The room is full of Bill’s work. About ten framed posters lean or hang on the walls having migrated from the art school bar.* (#litres_trial_promo)

As we entered we passed two large canvases, GET YOUR HAIR CUT and MAKE SOUP. Since I last saw them in the union bar I’ve read, watched and researched the Drummond canon, spoken to fans, friends and collaborators and come to appreciate the extent of Bill’s range … and it’s fair to say MAKE SOUP is not the work that defines him in the public consciousness. No. That’d be THE MONEY;* (#litres_trial_promo) an event chronicled in a film titled The K Foundation Burn a Million Quid.

I begin by asking if being Bill Drummond is sometimes a hindrance to work like The17.

‘It is something that I think about. Not all the time but … and I’m not the only person this happens to, it happens to most people that have done certain things. It casts a long shadow. I can feel that stuff I’ve done in the past will cast a shadow over whatever I do from here on in and there are times when that can get to me and it has influenced, to an extent, the way that I work. I have evolved ways of working where my name might not be attached to something.

It just so happens that piece thing behind you there, 40 BUNCHES OF DAFFODILS, that very thing, I’ve been doing that for about nine years now − I did it last week in Southend − and it’s got nothing to do with me. I go out in the street, I’m just a man, I’ve got a box of daffodils and I hand them out. There is no explanation. I don’t go out there to explain what it’s about. I do it and some people say, “What’s this about? Is this some sort of promotional thing?” and I say, “No no, I just want to give out forty bunches of daffodils.”’

Do you like that anonymity?

‘Yes, I like that. When Penguin were going to be putting out a book of mine called Bad Wisdom, at that point I wanted to call myself “W.E. Drummond” in that tradition of writers having two initials and their surname − which goes back to a time when most businesses were like that, WH Smith or whatever − but Penguin weren’t having it.

Whereas, when I first started doing The17, the first place we did it in the UK was in Newcastle. I’d posters designed just saying “The17 − a choir, blah blah” and I thought, “Wow, this looks so good! Who wouldn’t want to come along to something called ‘The17’!?” Of course, tickets weren’t really selling and the guy said, “Look, Bill, we’re going to have to stick your name on this,” and I really didn’t want it to be but I realised that I had to. I do realise with The17, when I do it publicly here, I have to attach my name to it just to make it work. I still balance doing that with going into all sorts of places and doing The17 where they don’t know who I am. It doesn’t matter.’

Months later, when I mention this to Stanley Donwood, he laughs:

‘This is why I love Bill Drummond’s work; it’s a constant series of genuinely inspired and brilliant ideas that somehow always seem to go awry or sideways; a constant cycle of admitting he doesn’t know what he’s doing and is probably naive or an idiot; but so fired with it. I find that inspiring. You know, who wouldn’t want to go along to something called “The17” with a great red painted sign? I would.’

Do you think your media caricature as a money-burning pop star has hindered the message and impact of subsequent work?

‘I know what you’re saying. I don’t know. I think I live a pretty unsociable life so I don’t get into situations much where these conversations can happen. I’m usually so focused or wrapped up in what I’m doing at that moment … Even when I’m being interviewed by a journalist, they don’t seem to ask those questions or maybe they tip-toe around them but then, when they write up their piece … it’s there. Maybe the first third of the feature will be a potted history of Bill Drummond. They feel that, if they don’t put all that in, whoever is reading the piece won’t know who this person they’re writing about is and I don’t know if that’s because I’ve never particularly gone out to have a large profile as a personality, maybe they’ve got to give that history to say, “Look, this person has been working for quite a long time in some sort of way and there’s some sort of thread here that leads through to where he’s at now …” I don’t know.’

You’ve always pursued that thread with a strong work ethic; is that linked to your Scottishness?

‘It is that, it’s very much that; that’s the background I come from, that’s the attitude. I’ve never been drawn to decadence. I’ve never been drawn to that thing of “the wild artist”, it just doesn’t interest me. The work ethic is … it’s not work for work’s sake. I get wrapped up. I get driven. The big motivation is that “life is short”. I’ve got a lot of things I want to get done. I could die tonight, that’s always there; and I’m always excited by what I’m doing. Exploration. The next thing.’

Do you see a pattern or progression in your work?

‘Usually, I can look back on what I’ve done − or look into myself − and see a theme. It’s almost always like I’m gnawing at the same bone or scratching the same wound. The17 this afternoon and “Doctorin’ the Tardis” − in one sense they’re a million miles apart, in another sense they come from a very similar place.’* (#litres_trial_promo)

• • • • •

You often relate your ideas and journeys in a very characteristic first-person style when you write – often in retrospect, often in the form of a diary or log.

‘Yes, although some of the time I cheat. Sometimes I write in the present tense although it’s been written after the event and I’m aware, in the sense that all writing is lying, that I’m telling a story so I’m leaving out a percentage of things in order to tie a thing together so that it has a beginning, a middle and an end, and I will do that unconsciously. I don’t set out to do it but somehow I’ve learnt to do that. Sometimes I look back and think, “I’ve just learnt these tricks,” and sometimes I try to break free of that − I can see my own clichés.

I’d like to think I could write a proper book with one whole story, like a novelist does but I guess, for a successful novel and definitely a successful film, you have to have something that happens in the first ten minutes or the first X amount of pages in a novel that sets something up: Something has now happened that changes everything – you’ve got to get to the end for it to resolve itself, that’s what takes you through. That doesn’t really happen with my things.

You mentioned earlier that your writing is episodic, Dan. That’s what my stuff is and that’s what will stop it from ever crossing over commercially, I think. That’s the reason people can maybe get so far with one of my books and then go, “Okay, I get the picture,” you know? There’s no plot, it’s not going to go anywhere particularly.

‘When I was eighteen I read On the Road by Jack Kerouac − huge influence on me; that and Henry Miller is what got me wanting to write.

When they brought out the scroll of On the Road a couple of years ago I reread that and it was weird. I’m now, you know, quite a bit older than Jack Kerouac was when he died − he was young when he wrote it − and it’s only now that I realise “but there’s no story here, there’s nothing!” He could have cut that book off at any point, it has no conclusion.’

Has that influenced the way you see your role as a raconteur?

‘It was never a conscious thing; it wasn’t until me and Z, Mark Manning and I, went to New York to do Bad Wisdom* (#litres_trial_promo) and we became like a double act, reading and telling the story, that I started learning how to actually talk to an audience. I knew I didn’t want to do it with a microphone. I knew I wanted to keep it as intimate as possible but I was aware that a craft was being learnt − it was an act to a certain extent but I knew that it also had to be for real. I know that, every time I go out and tell a story, like with The17 this afternoon, which I’ve told who knows how many times, I’ve got to somehow reach down into myself and make it real, in the same way as an actor has. Now, the last thing I ever wanted to be was an actor, but I know that’s what I’ve got to do and that has now become a big part, to use a cliché, of my practice as an artist; to get out there and tell stories and make it work, draw people in.

‘There’s another thing to this too. My dad was a minister in the Church of Scotland and in 1963 we did an exchange. He took over a church in a small town in North Carolina and the minister from that church worked at my dad’s church in Scotland. We went and lived in their house for three months and they came and lived in ours. Then, in 1993, we went back. It was just for a week or so but my dad was asked to give the sermon in the church there. Now, I grew up seeing my dad give sermons every week, as a kid, and I didn’t think about it, you know? “He’s just my dad.” When I was very young I’d be off into Sunday School by the time he got to the sermon … anyway, my dad was asked by the regular minister to come up and give the sermon, “We have Reverend Jack Drummond here …” and he got up out of the pew and started walking backwards down the aisle and started talking straight away. He got to the front and started going into it and I thought, “My dad’s got an act!” It had never crossed my mind (snaps fingers) and he was really good at it! He had them in the palm of his hand and the guy afterwards, the minister, said, “God, if I could roll my Rs like you, I’d be able to charge X amount more as a visiting preacher!” (Laughs) Which in this country, especially in Scotland, would never be said but that’s how Americans think, and I really learnt something from that. It’s not that I’m trying to imitate my father at all …’

But it’s in you.

‘It’s in me. And I realised I must have taken that in from a very early age − to get up and stand in front of an audience, no amplification, no band. You know, you’re not hiding behind the loud sounds of your guitar or the drums, or everything else, it’s not even that you’re hiding behind a tune. It’s just you and those people there and you’ve got to communicate something and leave something behind.’

You don’t think of yourself as a writer, though?

‘No. I’ve written books but I’m not a writer. I’ve made records but I’m not a musician. I can pick up a guitar or sit down at a keyboard and play some things but I don’t think of myself as a musician, never have done. I don’t think of myself as a writer, don’t think of myself as a painter … I went to art school by accident and I fell in love with painting. I was pretty good at painting too. That’s what I thought I was going to do and then, while I was there, I rebelled against the whole thing. Maybe I realised I wasn’t the genius I hoped I would be but I also thought, and this is going to sound arrogant, “I don’t want to spend the rest of my life attempting to make things to sell to rich people.” You know, one-off things.

I was then beginning to read, as I said, Kerouac and Miller. I liked the idea that with writing you could buy the paperback, everybody could buy the paperback and it was the same everywhere; and the same with music − a seven-inch single. I wasn’t thinking of getting into pop music at that point but I thought − the example I gave myself at the time and remember writing about is that Andy Warhol’s seven-inch of “Penny Lane” by The Beatles is no better or worse than my version. I liked that democracy.

‘So, I walked out of art school, walked away from painting and thought, “Well, I’ll write. To do that, I’ll have to go and live life and do all sorts of jobs, go all over the place.” It’s not like I just wanted to sit down and write novels about relationships and all that kind of stuff. I wanted to get out there into the world and live a life but I realised after a while that I wasn’t really a writer. I don’t know at what point it dawned on me but I was actually doing everything with the head of somebody who’d gone through the British art school system circa early 1970s and that’s still the overriding thing. So the storytelling, doing the posters, coming up with a way of allowing myself to do the paintings all comes from that.’

You say ‘allowing myself to do the paintings’ and you do often seem to structure work around a dogma or set of rules − allowance and denial.

‘It’s not like I’m “into denial” like some sexual or perverse thing … It’s like when I was making three and a half minute pop records; there’s no point making them longer than three and a half minutes. The way that these things are communicated to people is via radio, initially, and radio stations don’t want to play anything longer than three and a half minutes. If it is, they start fading it or talking over it. Also, with a pop record, any record, any recorded music, you can only have it within so many megahertz − you can’t have really high sounds or really low sounds because it can’t exist on a piece of vinyl or an mp3.’

You see a beauty in restriction?

‘Yeah. Like, with oil paints – not that I use oil paints now – you know that this colour and that colour, they can’t mix chemically – so you’re always aware of it.

Doing the posters over the years, I always thought, “Trim it down. Trim it down.” Whereas they started off a lot wordier and there wasn’t much difference between the posters and the writing in the book.’

Are you happy with the term ‘artist’?

‘I’m never happy with that at heart, no, but anything else I try to come up with, it doesn’t work. There was a time when I thought, “No, I’m a poet, that’s what I am, just so happens I don’t use words …” and I tried to convince myself of that but I knew it was even more pretentious and would need even more explaining. There was a period when I was reading more poetry than I was looking at or thinking about art … I don’t know, saying you’re an artist has always had, maybe should have, that pretension. “Oh, you’re an artist are you? That what you think you are? You’re an artist now?” Pop record making was only (holds up thumb and index finger) that much of my life. There was a lot before and after that.’

The advent of The17 seemed to coincide with a shift in popular music away from the single voice to a more choral sound.

‘I think it’s a zeitgeist thing. I think I’m just part of a … this didn’t come into The17 book but I could have started from another point of view:

I buy an iPod. Theoretically, I can have every piece of music that I have ever wanted to listen to on there and I can listen to it when I want. So I get all these tracks and I start flicking through, this one, this one, this one − that’s just me though, jaded − but then I notice my thirteen-year-old doing the same thing, “flick, flick, flick, flick”, or she hears something on an advert, likes it, types it into Google, downloads it − whoosh, she has the band’s whole everything. She doesn’t know what decade they’re from, where they’re from but she’s got it all and maybe listens to it for a week and then it’s gone. Bang.

Next week it’s something else.

‘Something has vastly changed, really hugely changed. When I was a kid, to have an album cost you quite a bit of money. You invested in it. When you got it, if you didn’t like it, you accepted there were maybe only two tracks you liked but you worked at it and you ended up liking it, learnt to like it − that’s not going to happen now, it’s different and I’m not saying anything’s better or worse, it’s just changed. What’s happened since the whole downloading thing has kicked in big time is the live side − going to see the act live is far more important; last year with Leonard Cohen over here − whole generations said, “We’ve got to go and see Leonard Cohen.”

It doesn’t matter if they buy the album …’

It’s the event.

‘The event, yes. Look at the rise and rise of the amount of festivals. It may be a bubble that’s going to burst but it’s now about time, place and occasion – all of those things that I’m dealing with in a different way with The17 – that is what people are going for. It’s no longer contained within the recording.

Some people now, people more of your generation, fetishise vinyl and it’s young people who are buying into a want, a need for music to be more solid, the sleeves bigger …

So those are all reflections of that thing. Of course I hear Arcade Fire and Fleet Foxes and I love it but that’s just me, that’s because of my age and the way it reminds me of things from other times.

I didn’t bring it up this afternoon but I know, over the years, any time I’ve heard choral singing music my ears have gone out to it and that’ll be because I sang in choirs as a kid.’

Perhaps part of the magic of singing in church as a child is that you’re unaware of what you’re singing about.

‘It’s just the sounds, yes, and I’ve read recently how − I can’t remember the composer − he wanted less words, more long vowels and more harmonies because that’s what’s really being communicated. That’s what has the power in religious music. It’s not the words, it’s the sounds, it’s the voices.’

Are you finding that many members of The17 are being affected by the experience?

‘I don’t know. I don’t know enough people … I’ll go and do something like today but I don’t know what the long-term effect is. I’ve got no idea.’

• • • • •

Stoke Newington, London

March 2010

Bill is sitting on his roof − the roof where he writes, weather permitting.

It was here, surrounded by the ambient noise of outer London, that he wrote much of his book about The17* (#litres_trial_promo).

Earlier in the day, when I expressed concern that the portrait we’re here to take might look contrived, Bill patiently pointed out that, since he wasn’t in the habit of writing on his ledge with other people looming over him, it was contrived whether I liked it or not and we should probably just make the best of a contrived situation and not worry about it. So we do; Bill with his notebook and tea, Lucy and I teetering precariously above the guttering and the drop, trying to frame the shots.* (#litres_trial_promo)

We speak about Lady Gaga. Bill loves Lady Gaga; loves her complete ease and ownership of pop. She has compromised nothing, he says, she has created a whole universe and now straddles it, unsurpassed.

Bill tells us that, for a few weeks last year, he and fellow ex-KLFer Jimmy Cauty were in agreement that the only thing which would tempt them back to pop music would be to work with Lady Gaga.

‘Jimmy said he was surprised she’s not telephoned us yet.’

• • • • •

After leaving Bill’s house, I’m struck by the thought that the way he records and narrates his work, however unreliably, may be a stratagem to buttress and bolster its shape – for himself as much as the layman. His world of mad doings only lines up in retrospect when viewed from the justified headlands of 17, How To Be An Artist and the other written records of his work. His books are accepted histories of a lifetime of tangential missions into the unknown and he takes such care to define the narrative path because he knows the chaotic abyss that lurks either side of his stated methodology.

Even the story that there’s no story – no meaning behind a decision – ‘Nothing to see here’, is a sleight of hand way of working.

He generates the story and embodies it, but sometimes his stories are not enough, the wilfulness of his acts too great to be constrained within the books, films, music and statements he makes in their wake – as with THE MONEY – and long shadows threaten to swallow him up … but he writes and talks his way out of it, making something new from the fallout; forms a new plan; invokes a new dialectic and moves on.

RICHARD LAWRENCE (1958– ) is a British letterpress printer based in Oxford.

He started printing at school in 1970 and bought his first press (a Heidelberg platen) in 1976. As well as commercial printing work, he teaches letterpress and linocut courses at the St Bride Foundation in London.

RICHARD LAWRENCE (#ulink_02d67d69-6d97-55f9-b5af-7ce6e8890923)

Widcombe Studios, Bath

2008–2011

Returned home to Bristol from Norfolk, I found myself in a post-MA slump. Unsure of what to do next, I began working on a house renovation, returning life to a wreck, digging retrospective foundations where the Georgians hadn’t seen fit – claggy mud, army boots, two pairs of trousers, early dark starts, insipid rain … it wasn’t much like art school. ‘Well, at least I’m still working with my hands,’ I’d think, dubiously.

After a couple of months, around Christmas 2008, my father told me he’d met an interesting Bath-based letterpress printer who worked with a lot of old kit. I’d written nothing since talking to Bill (I’m not sure I’d even listened back to the tapes). Something about coming home had stumped me and I wasn’t sure where my idea for the book was headed. So I’d stopped. But something about the idea of talking to a printer brought thoughts of the brilliant time had in a Thames boat yard back to mind. I’d known very little about boat building but the craftsmanship and enthusiasm I’d discovered in Henley had inspired and re-energised the whole airship project – my MA too, perhaps – so I telephoned the printer, Richard Lawrence, and asked if I could talk to him about his work. He wasn’t keen, explaining it would likely be very disappointing and tedious for me since what he did was in no way arty, but we arranged to meet in any case after I’d explained that few things could be as disappointing as digging footings with a spade in the freezing cold.

Stood beside the River Avon, Richard’s workshop was a single-storey building with a pitched roof made of corrugated iron but held together with moss.

Mist from the river hung level with the gutters.

I remember the hefty padlock on the garage door was green and its long-term knocking had worn away a hollow in the wood behind it.

The first thing I saw once inside was a print of Fleet Street being consumed by fire and flood – one of a series of linocut visions by Stanley Donwood, an artist with whom Richard had worked for several years; the inky nous to the Donwood dash.* (#litres_trial_promo)

At the time of my visit they’d recently finished work on a project called Six Inch Records and remnants of the printed sleeves and card inners were piled up on the printshop’s central bench.

Once sat with coffee, Richard explained the division of labour:

‘I do this because I love the machinery and am fascinated by the process of squashing ink onto paper. It’s nice if what you end up producing looks nice but that’s not actually why I do it. (Laughs) I mean, obviously it’s a lot more satisfying to produce something that looks good; and it really doesn’t take any more effort to produce something that looks good than something that looks bad.

Against which it’s very interesting dealing with Stanley. (He points up to a drying rack of prints) Those posters are very obviously made up of broken old wood type. If I had my printer’s hat on I’d go through and replace all the letters that are wonky and fiddle until it all printed solid and so on but that’s not what he wants, he wants it to look like that. That’s why it’s printed on brown paper. (Laughs) It’s rubbish!’

You’re the technician and Stanley’s the artist, then, but where’s the tipping point do you think? What is the difference?

‘In my case, the difference is that I do not have the artistic skill to produce an image that looks nice. So the tipping point between art and straight printing is probably the ability to produce a printing surface that is considered a piece of art. Recently I’ve fallen back on this theory: “I am someone who knows how to put ink on paper” … but it’s very interesting, this distinction between craft and art.

Printing is a design skill, a practical application of common sense.’

Editorial common sense.

‘Exactly. It’s a very difficult dividing line and there’s an enormous amount of expediency in what I do which I don’t think people appreciate. That’s something that Stanley is very good about, actually – he’ll have a vague idea of what he wants but then quite happily bend it or, you might say, be inspired by what’s available. That’s the essence of all the typography that I do. I have an idea of what it would be nice to do and then I think, “Well, what have I actually got with which I could do it?”

‘Somewhere along the way I spent some time at Reading University doing a History of Printing, Design & Typography degree and one of the things that people there say – and it’s very much the way I feel, working with letterpress – is that letterpress is extremely good training for typography and design simply because of the number of things that you can’t easily do. You’re constrained in all sorts of ways and you’re made to work with what there is. It’s a very interesting exercise.

‘A few years ago I had the order of service to do for a funeral and there was a lot of copy in it, a lot of words, and I found I’d only enough of one typeface to typeset the whole thing. You’re then confronted with the problem of how to distinguish all the instructional headings for the congregation, delineate between hymns and pieces of text and, armed with one size of one typeface in roman and italic you can actually produce something that is extremely … I mean, “functional” makes it sound boring but you can produce something that works extremely well and looks good, having started with one option.

If I’d been doing it on a computer it would have been very easy to have as many sizes of type as I wanted and as many fonts but it would have been less thought out – that’s the other constraint with letterpress, if you’re typesetting a lot of material, doing it by hand, it takes a long time and you can’t, at the end of it, say, “Oh, I think it would look better if it was a half a point bigger,” and click a button. It doesn’t work like that. You have to decide before you start what you are doing. It inspires you to plan.’

• • • • •

There are three presses in the printshop proper. An Albion hand-press stands in a corner with an air of solid menace. Next to this a black and chrome press runs the length of the workshop wall – shrouded by a greenish tarp. ORIGINAL HEIDELBERG CYLINDER. 1958. Wheels, handles, dials and levers poke out at intervals, like Dalek punctuation.

To the right sits HEIDELBERG 1965, a smaller machine which Richard now starts and lets run. As the paper in the feed is fed up to the hinged ink jaw – the myriad movements are crisp and hypnotic – I realise the noise is taking me back to my childhood and the top-left-hand corner of Wales.

‘Pish ti’coo; Pish ti’coo; Pish ti’coo; Pish ti’coo …’

Ivor the Engine reincarnated as a press* (#litres_trial_promo) and, indeed, all the presses here are substantial, locomotive-like apparatuses – sat still and quiet now but potentially very loud and powerful. Richard resembles a lion tamer sat in their midst.

‘The thing that puts a lot of people off owning one of these is the sheer size – it weighs almost exactly a ton.

Like all letterpress machines, you need an inky surface and a piece of paper and you squash one against the other. That’s it. That’s printing.

This press achieves that by running ink rollers over the surface, and the really clever bit of this machine is the feed mechanism which, rather ingeniously, can suck just one piece of paper up, deliver it to the gripper-arms which then rotate, carrying the paper.’

He hands me a newly printed sheet, the slight indentations of the pressed type just visible if I hold it up at an angle to the light.

‘Most of the trick to running this is knowing how to make it pick up one sheet and not two and not none. What you get good at, after a while, is looking at the pile and listening to the noises the press makes so that, if it does do something wrong, you can very quickly figure out why. You can adjust the number of suckers turned on, you can adjust both the height and strength of the blow that comes through the pile, you can adjust the angle of attack of the suckers, you can adjust how fast the pile is driven upwards and, depending on the thickness of the paper, what height it’s picked from. By adjusting one or all of those things, you can get it to pick up one sheet of anything you want – from very thin paper right up to beer-mat board. Have you ever made balsa wood aeroplanes? They’re done on these, that’s how you print and cut out the pieces for the kits – die cutting. (Rummages through a box file on a shelf by the sink) That’s a cutting die and that’s what it does.’

Richard puts a rectangular piece of wood on the bench. A maze of metal blades project up from it, surrounded by small, close-fitting blocks of foam.

‘The important bit is the shaped cutting rule – it’s quite sharp. If you imagine pushing the die into a piece of card, it would tend to stick in it, so the foam is there to push it apart again.’

Are fold-lines made in the same way but with blunt rules?

‘Yes, the folding rules are rounded on top and very slightly lower than the ones which cut. These are made in Bristol. If you ask people, “What’s printed the most?” the bulk would say newspapers or books when, in fact, it’s packaging material. Cereal packets win hands-down. The vast majority of printing around the world is for packaging and along with packaging comes boxes and for those you need die cutting.’* (#litres_trial_promo)

Rooting through another box, Richard pulls out a block comprising two interlocking parts. A piece of paper or card placed between these matched male and female dies* (#litres_trial_promo) will emerge embossed – the design pressed through the page. This is blind embossing, he explains, ‘blind’ because it is an inkless process, the pressure of the press moulding the material into a relief – the definition wrought by the light.

The examples of the practice that he proffers have a wonderfully tactile quality. Fingertips trace the contours of a set of Stanley’s bears – stamped into a furrowed map for a Six Inch Record outer, a linear Braille-scape.

I hadn’t considered printing presses being put to work ‘dry’ in this way. The technique seems so elegant. I ask how Richard cleans his type and presses down.

‘White spirit. You can use paraffin but it leaves a slightly oily residue behind.

One thing I run into which irritates the hell out of me is that the whole letterpress printing thing has been taken over by “creative” people, artists and such, some of whom have, what I consider to be, absurd ideas about safety. There are aspects of this which are clearly very unsafe – don’t stick your head in a moving press; don’t take a handful of lead type and eat it, all that sort of thing – but a lot of people, particularly Americans, are terrified of solvents … and you can get inks that, instead of being based on linseed oil, are based on soya oil; you can use cooking oil or soya oil to clean down the machinery afterwards, you can … but it leaves it in the most foul, sticky, gunky condition – if you know what you’re doing, washing a machine up with white spirit, you’ll perhaps use two fluid ounces.’

Can you tell me a bit about your inks?

‘Oh, they’re all boring old linseed oil based inks – you take linseed oil and boil it, then grind pigment into it. I don’t personally do that, there’s an ink making company in South Wales who treat me extremely nicely. I started using them some while ago. I asked them, “Could you possibly, maybe … ?” and they said, “Oh yes, not a problem,” and now they produce six different pots of bespoke colours for about £20 apiece which was about a third of what I’d expected to have to pay. I subsequently looked them up on the internet and they turn out to be Britain’s major ink producers – they’re the people who supply Fleet Street – so what they’re doing piddling around producing pots of obscure colours for me I’ve no idea; but I love them for it.’

Richard crosses over to a shelf, takes a lid off a tin and holds it out. Inside the ink resembles emerald engine grease – sickly, fat and viscous.

‘Here is a tin of green that I bought the other day.’

He up-ends it. Nothing happens.

‘I could probably leave it upside down for an hour before any came out; but some inks are thinner than others. White is a problem.’

He opens a tin of white and lays it sideways on the bench. An ominous bulge begins to form, like angry custard.

‘As you can see, it’s almost able to flow. White is a notoriously difficult colour to work with because white, as a pigment, is lousy and getting enough of it into stuff is very difficult. That’s why, if you ever see white type on black in a magazine it was almost certainly printed black onto white paper rather than the other way round.’

How is white ink made?

‘It’s usually titanium and other stuff – aluminium oxide sometimes, depending upon what you want. Most of the pigments are inorganic chemicals.’

Gone are the days of beetles for blue and suchlike?

‘Um, mostly. (Laughs)

I don’t know what some of the pigments are that they use. Having said that, I bought all these tins of ink for the same price and some had noticeably less in than others because the pigments involved were just that bit more expensive. To this day, a kilogram of blue will cost you more than a kilogram of yellow.’

• • • • •

At this point we pause for more coffee and a Penguin biscuit. Richard sits framed by a stacked tower of drawers that rise floor to skylight, each one partitioned into myriad cells – packed with an unseen type, filed away; dormant words.

Tall, bearded, an L.S. Lowry figure in jumper and gilet, he seems quietly amused by most things – I suppose he’s what people would call diffident, but actually I think it’s another facet of his economy – he’s not one for small talk, reserves judgement. There’s nothing superfluous about him – he’s lean. A spare man.

‘It’s actually quite rare to find someone who is interested. As you’ve probably worked out by now, I’m interested in the technicalities of it. That’s what I get excited about.

The images are great and it’s nice working with people like Stan but it’s the whole business of “How does it work?” that actually excites me.’

Do many people track you down because you work with Stanley?

‘No, thankfully not, somehow it hasn’t happened. He’s very fair about giving me billings on things that I have helped him with but no one seems interested in me, for which I’m eternally grateful. But then, I’ve been to one or two of his launch events and he seems to have a habit of wandering around, not actually telling people who he is.* (#litres_trial_promo)

Having said fiercely that I’m not an artist, I’m actually a scientist by training. I spent the best part of twenty years working for a publisher in various editorial functions producing maths and science books. I like printing because I can understand how it works – if this bit doesn’t work it’s because that bit isn’t connected to the lever that makes it wiggle … and I can then do something about it. I’m very happy with this lot and if something goes wrong I can fix it.’

Where did you get your presses?

‘Well, the Albion in the corner came from an artist, a genuine artist, who made linocuts and worked at the art school at Banbury. He was getting on to retirement and needed to get rid of it so he advertised in the back of a magazine that I read and I bought it from him.’

Can it be taken apart?

‘It can to a certain extent, yes, but the main casting remains unfeasibly heavy and awkward to move; and while nobody knows what Gutenberg’s press looked like, it was probably very similar – except of course that his was made out of wood rather than metal.

While letterpress continued they were very useful, practical things – they made excellent proof-presses. So, rather than locking something up in a machine forme* (#litres_trial_promo) and all that – particularly on very large printing machines, terribly tedious – you could ink these by hand and print a sheet or proof very quickly.

‘The 1965 platen came from a printer in Oxford who was closing down. He’d made it to the age of eighty-something and his second replacement knee didn’t really take to it so he decided it was time to retire. I’d got to know him and, when it came time for the machine movers to come and take this away, he suggested that I had a word with them. They were essentially taking it away to recondition it and sell it on – probably for die cutting and blind embossing and that sort of thing. I think I gave them about £400 for it and they took it out of his workshop and dropped it at my house a mile up the road. £400!’

What is it worth now?

‘£400!’ (Laughs)

Really?