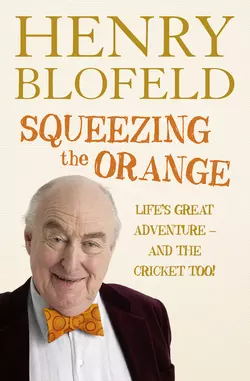

Squeezing the Orange

Henry Blofeld

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Хобби, увлечения

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 858.94 ₽

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 18.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The quintessentially English cricket commentator, writer, oenophile, bon viveur, collector and national treasure, fondly known as “Blowers”, tells his riveting life story.Born in Norfolk and educated at Eton and Cambridge, Henry Calthorpe Blofeld OBE, nicknamed “Blowers” by the late Brian Johnston, is best known as a cricket commentator for Test Match Special on BBC Radio 4 and BBC Radio 5 Live Sports Extra. His distinctively rich, cut glass voice and his vividly eccentric observations of life on and off the pitch, have made him a household name, not only in Britain but around the world, wherever cricket is played. Blowers has been close the the heart of the game for over fifty years and his career has taken him to the far corners of the earth. This autobiography, stuffed to the gunwhales with delicious anecdotes, brings his astonishingly colourful story bang up to date.