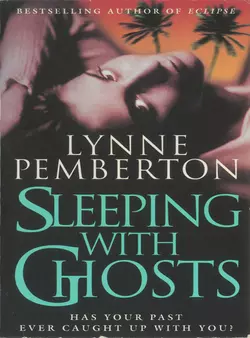

Sleeping With Ghosts

Lynne Pemberton

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 152.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A blockbuster novel of suspense, intrigue and revenge, from the celebrated author of Platinum Coast and EclipseKathryn de Moubray comes from a respectable English family. So when she discovers that her grandfather was a high-ranking Nazi and wanted war criminal who disappeared in 1944, she is devastated – and compelled to trace the family history that her mother, now dead, kept hidden for so many years.Adam Krantz, a New York art dealer whose family was wiped out in the Holocaust, is on a mission to find their legacy: an exquisite collection of paintings which vanished at the same time as Kathryn’s grandfather. Adam is convinced that the two are connected.They meet in St Lucia, and again in London when a priceless painting turns up mysteriously, amidst a storm of controversy. Despite the bitterness and betrayal of the past, the attraction between them grows stronger. But will it unite them or drive them apart as they unravel the extraordinary events that took place in wartime Berlin more than fifty years ago?