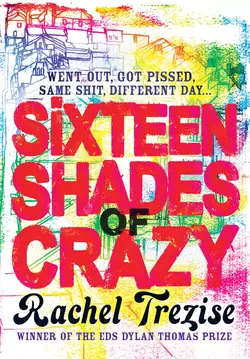

Sixteen Shades of Crazy

Rachel Trezise

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 152.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘Went out, got pissed. Same shit, different day.′Aberalaw, a tiny South Wales valley village where nobody ever arrives and nobody ever leaves. The new police chief has declared war on recreational drugs, resulting in an eighteen-month drought. The party-loving wives and girlfriends of local punk band, The Boobs, are getting desperate, both for drugs and thrills: Ellie, factory girl with dreams of a better life in New York; Rhiannon, hairdresser with a taste for violence and designer clothes and Siân, unappreciated, obsessive compulsive mother of three. Into their lives, enter the languid dark stranger, Johnny: Englishman, drug dealer and shameless seducer. In the space of just a few months, three women′s lives will be changed forever.Prize-winning writer, Rachel Trezise, dissects the morals and mores of a small Welsh village community with a scalpel-sharp pen and an incisive wit.