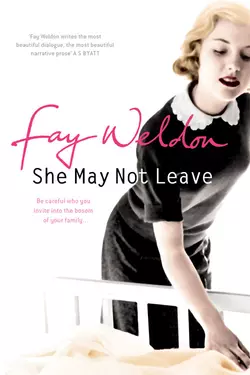

She May Not Leave

Fay Weldon

Be careful who you invite into the bosom of your home – she may never leave…A novel from Fay Weldon, the writer who knows women better than they know themselves.Hattie has a difficult if loving partner, Martyn, an absentee mother, Lallie, and a cynical if attentive grandmother Frances. She tries to do the right and moral thing in a tricky world, and always has. But she now has a baby, Kitty, which makes true morality rather harder to achieve. Somehow, money has to be earned. Into this household comes Agnieszka, from Poland, a domestic paragon. But is she friend or foe? And even if she is foe, and seems likely to bring the domestic world crashing down around their ears, can they afford to let her go? Well, no.Martyn works for a political magazine, Hattie for a literary agency. At work, too, integrity is suffering as the need for compromise becomes ever more pressing. And always in the background is Frances, tracing the family and social history. And not just family and society but the dwelling houses too; and all those girls and women (the au pairs, the child-minders, the cleaners) who've made Hattie what she is. Not to forget that hefty dollop of male genes which has also played its part – for Hattie's is a lively and none too respectable background – and now, finally, Agnieszka, come to claim her rightful heritage – which is, let's face it, everything. Will Hattie go to the wall? And poor little Kitty…Or will rescue come?

She May Not Leave

Fay Weldon

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#uc55df946-808a-58ce-a022-4cf7741572f7)

Title Page (#u1c62e168-d25f-5a96-a755-effb48a51f24)

Martyn And Hattie Have Employed An Au Pair (#uabddb7e3-4b19-507f-b3b8-3def049d79e8)

Frances Presents Some Authorial Background (#u71ec7936-fa09-5987-9914-532fd6892de7)

A Bit Iffy (#u44b559d8-2d4f-5a2c-9a59-437db7cecdd7)

Demotic Credentials (#u45789ba8-2fbd-5bd9-90e6-e4ef04fea56a)

Sebastian In Prison (#ud30d9610-c54f-5a74-8ea4-36e9c914c130)

A Further Ethical Discussion After Supper (#u86bd2f57-34bb-5970-971e-f310cb630120)

To The Left! (#ud2a4d403-d52d-594e-8f89-6880d1c51b44)

Acceptance (#u3a1cd007-c92f-5d81-bbea-79ddbdcf98e0)

Agnieszka Comes Into Hattie’s Home (#u37485eab-cec0-55ab-9200-86b7cb37e50c)

Frances Worries About Her Grand-daughter (#uddfa5213-84f1-5d44-9663-9872df4b312f)

The Effects Of Bricks And Mortar On Lives (#ufa3da690-f5f0-57f0-aac0-b837f7e06240)

Learned Characteristics (#u403d140f-5771-59c6-a0fb-343db858a51c)

Martyn On The Way Home From Work (#ud4c35939-23dc-5ab7-9fa5-bb2fbffc1a2b)

Martyn Comes Home To Agnieszka (#u42a9a849-6501-5920-8756-854503b2723a)

Au Pairs We Have Known (#u76b4ae24-df9e-5827-885a-fd95c60a3403)

Glossing Over Inconvenient Facts (#litres_trial_promo)

Child Support (#litres_trial_promo)

Martyn And Hattie Have A Tiff (#litres_trial_promo)

Men, Women, Art, And Employment (#litres_trial_promo)

George And Serena’s Household (#litres_trial_promo)

Hattie At Work (#litres_trial_promo)

A Good Au Pair And The Promise Of Life After Death (#litres_trial_promo)

Preserving The Peace Of The Home (#litres_trial_promo)

Dream On (#litres_trial_promo)

Martyn Is Alone With Agnieszka (#litres_trial_promo)

Another Country (#litres_trial_promo)

Agnieszka And Martyn Go Shopping (#litres_trial_promo)

Ordinary Women (#litres_trial_promo)

Chocolate-Covered Prunes (#litres_trial_promo)

Coming Over (#litres_trial_promo)

Suspicions (#litres_trial_promo)

Frances In Love (#litres_trial_promo)

Agnieszka’s Passport (#litres_trial_promo)

Animals (#litres_trial_promo)

The Christening (#litres_trial_promo)

Hurrying Men Away (#litres_trial_promo)

The Boss Comes To Dinner (#litres_trial_promo)

Cooking Disasters (#litres_trial_promo)

Agnieszka And The Internet (#litres_trial_promo)

Maternal Panics (#litres_trial_promo)

Churchyard Drama (#litres_trial_promo)

Mad Plans (#litres_trial_promo)

Martyn Confesses (#litres_trial_promo)

Hattie At The Cattery (#litres_trial_promo)

Hattie Gets Promotion (#litres_trial_promo)

Two Weddings And A Funeral (#litres_trial_promo)

Martyn And Agnieszka In Bed (#litres_trial_promo)

Two More Nights (#litres_trial_promo)

Other Books By (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About The Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Martyn And Hattie Have Employed An Au Pair (#ulink_59aa9302-832f-5ea2-8f98-dbd7d1c63130)

‘Agnieszka?’ asks Martyn. ‘Isn’t that far too long a name? If she wants to get on in this country she’ll have to shorten it. People are just not familiar with sshzk.’

‘But she won’t want to shorten it,’ says Hattie. ‘People have their pride, and a loyalty to the parents who named them.’ ‘If we pay her,’ says Martyn, ‘she may have to do more or less as we ask.’

Martyn is in conversation with Hattie in their economical, comfortable first-time-buyers’ house in London’s Kentish Town. Both are in their early thirties, handsome, healthy and educated, and for reasons of principle not lack of affection are not married but partnered. Baby Kitty, twenty-four weeks old, sleeps in her cot in the bedroom: Martyn and Hattie fear that she may not sleep for long. Martyn is just back from work. Hattie is ironing: she is unused to the task, and making a rotten job of it but she is, as ever, doing her best.

Hattie is my grandchild. I spent many years bringing her up and I am fond of her.

They have been talking about the possibility of employing an au pair, Agnieszka, recommended by Babs, a colleague of Hattie’s at Dinton & Seltz, Literary Agents. Hattie took maternity leave: now she wants to return to work, but Martyn is resistant. Not that he says so, but Hattie can tell because of his feeling that the girl’s name is too long. About Agnieszka they know very little, except that she has worked for Babs’s sister, the one with triplets, and left with good references.

In the circles in which Martyn and Hattie move as many babies are implanted as conceived, and so do often arrive in twos or threes. Kitty was an accident which served, after initial confusion and dismay, to make her the more precious to her parents. Fate had intervened, they felt, for the good. Man proposes, God disposes, and for once the result was satisfactory.

‘I don’t think it would be right to ask her to change her name on our account,’ says Hattie. ‘She might be offended.’ ‘I am not sure,’ says Martyn, ‘that we should define right as what does not offend.’

‘I don’t see why not,’ says Hattie. Her brow darkens as she comes to grips with what Martyn has just said. Surely not offending other people has a large part to play in what is defined as ‘right’? But since Kitty’s birth she is less sure than before about what is right and what is wrong. Her moral confidence is being eroded.

She can see it is ‘wrong’ to jam a comforter in baby Kitty’s mouth to stop the crying, as poorly educated mothers from the housing estates do. ‘Right’ would be searching for the cause of the crying and attending to that. If this is the case she chooses wrong over right at least five times a day. She can see she is also guilty of élitism, in not wanting to be numbered as one of the estate mothers. The family income may be currently below the national average, but even so the notion of her own superiority increasingly flits across her mind. Does she not read books about child-care, instead of waiting two weeks for the health visitor to turn up? Surely she is someone who controls her own destiny? But she has been so a-mush lately, so driven by hormonally based emotions, so much a prey to unaccustomed resentments and gratifications that she swings from conviction to doubt within minutes. She did wake this morning, leaning over to the crib beside the marital bed to put the comforter in Kitty’s mouth, with the comforting understanding that people are as moral as they can afford to be, no more nor less. She should not blame herself too much.

‘Then you should see why not,’ says Martyn. ‘Social justice can’t be achieved by simply letting everyone do what they want. A fox-hunter might well be offended if you pointed out that he was a cruel sadistic brute, but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t say it. We should all be working towards the greatest good of the greatest number and sometimes hard words and tough choices must be made.’

‘How would telling someone to shorten their name further social justice?’ asks Hattie.

She feels mean and petulant; she knows she’s being obstructive, but if Martyn can be so can she. Hattie has already asked Agnieszka to come round for an interview but hasn’t told Martyn. She has not yet quite brought him round to the idea, though the arrival of the electricity bill and the community charge, both in the morning’s post, has had its effects. Hattie must go back to work. Really there is no choice.

‘For one thing,’ he says, ‘think of the delays while the name was spellchecked. Agnieszka Wyszynska! Computer operators all over the country will be at their wits’ end. It would be a simple kindness to others to simplify it.’

‘What to?’ asks Hattie. ‘What do you suggest?’

‘Agnes Wilson? Kay Sky? Short and simple and co-operative. She can always change it back when she goes home to Poland.’

‘I have no problem spelling Agnieszka Wyszynska. You just have to get used to certain combinations of consonants and realise “y” is a vowel. But then I studied modern languages and I’m not bad at spelling.’

Hattie is indeed good at spelling, but when she talks about Agnieszka’s pride she may well be talking about her own. People tend to invest others with their own qualities be they desirable or otherwise. The generous believe others will be similarly generous: the liar accuses the other of lying: the selfish see selfishness in everyone else. If Hattie declines to use Microsoft’s Spell-check, preferring to use her own judgement, or call her great-aunt the writer if in doubt, it is because she too has her pride. She has a highly developed superego. This may well be why she and Martyn, a man from the working-class North with high social principles and well-developed class-consciousness, are joined together in committed partnership, if not holy matrimony.

Hattie comes from the bohemian South, from a family for whom morality tends to concern itself with the integrity of a particular art form and the authenticity of emotion. It is a family in which Hattie’s particular temperament is seen as something of an anomaly. There is something rigorous and nonconformist about her which echoes the same tendencies in Martyn. In this she is unlike her mother Lallie the flute player, or her grandmother Frances who is married to an artist currently in prison, let alone like her great-aunt Serena, the well-known writer. Heaven knows through which genetic route ‘the responsible tendency’, as Frances refers to it, has come. It may well be from Hattie’s father Bengt, a schoolboy at the time of Hattie’s conception. But who is to say? Bengt was so quickly whisked off to Sweden by his parents for a new and better start in life, that the details of his character were never fully apparent to Lallie’s family. We could only watch and observe Hattie as she grew to find out what she would be like.

Bengt was to become a pharmacist in Uppsala and live quietly and decorously with a wife and three children, so with time it was assumed that he had left responsible, competent, if possibly rather priggish genes behind. The single brief act which resulted in Hattie occurred in what was known as the Tranquility Hut at the progressive and very expensive school the two young people attended.

Once a year, if Lallie can find a window in her busy international schedule, Bengt will bring his family over from Uppsala to visit her and Hattie, his ill-begotten daughter. Everyone is most courteous on these occasions but can’t wait to get back to normality, which is to forget any of it ever happened.

Hattie is polite to her father but cannot be very interested in him. She found out and filled in details of his medical history to the researchers at the hospital where she went for antenatal care, but could find nothing but good health and non-event to report. If Hattie didn’t resemble Bengt other than in a certain heaviness of jaw and brusqueness of temperament, she would have thought her mother had made a mistake and somebody quite other was responsible for her, Hattie’s, existence. Like the rest of her family Hattie does like things to happen. Bengt is, frankly, dull.

But since she had Kitty it’s the wrong kind of things which seem to happen. The district nurse, who calls regularly because Hattie has declined to join the weekly mothers’ and babies’ club, and this goes down on her notes, complains that the baby’s motions are too loose and accuses Hattie of eating garlic. Hattie has not eaten garlic since Kitty was born. The district nurse does not even ask but just assumes Hattie is the kind of mother who would. Is this how she seems to others? Irresponsible, biddable, and dumb?

‘Anyway,’ says Martyn now, ‘it’s all hypothetical. We don’t need, want, let alone can afford an au pair. Forget it. It’s just an idea of Babs’s. I know she’s your friend but she has an odd idea of how the world works.’

Martyn is not too keen on Babs as a friend for Hattie and not without reason. Babs is married to a Conservative MP and although Babs declares herself scornful of her husband Alastair’s political opinions, Martyn has a feeling that something political must surely rub off in the marital bed, and that perhaps some essence of the amended Babs could in turn be transferred to Hattie. He feels that he has already personally osmosed a lot of Hattie’s being by virtue of sharing a bed with her, and is happy enough about this. Why should he not? He loves her. They have the same outlook on life. The arrival of Kitty, half him and half her, has bonded their beings more closely still.

Hattie has no choice now but to tell Martyn the truth. Not only has she already spoken to Agnieszka of the too long name, but she has told Neil Renfrew, executive director of Dinton & Seltz, that she would like to come back to work within the month, having sorted out her child-care arrangements. Martyn and Hattie had decided to opt for a year’s leave of absence: now Hattie, unilaterally, has halved that. Neil has found a space for her in Contracts, working opposite Hilary in the Foreign Rights Department. Hattie has lost some seniority as a result of taking maternity leave but it’s not too bad. She should be back on career course within the year. Hattie reads and speaks French, German and Italian; she is suited to the job, and the job to her.

She would perhaps rather be working at the more literary end of the agenting business – it’s more fun: you go out to lunches and talk to writers – but at least in foreign rights you go to the Frankfurt Book Fair and deal with overseas publishers. Eastern Europe is an important and expanding market in which Hattie will need to be active. The job is going free since Colleen Kelly, who has become pregnant after five years of IVF, is stopping work early to write a novel. It has occurred to Hattie that Agnieszka will help her to learn Polish.

‘But you haven’t even met her,’ says Martyn now as Hattie reveals truth after irritating truth. ‘You have no idea what’s she’s like. She could be part of some international baby-theft ring.’

‘She sounded very nice on the phone,’ says Hattie. ‘Wellspoken, quiet and calm and not at all from the criminal fringes. Agnieszka looked after Alice’s triplets until they moved to France last month. And Alice told Babs that she was a gift from heaven.’

‘A gift to you, perhaps,’ says Martyn. ‘But what about Kitty? Do you really mean to compromise our baby’s future in this way? Research shows that babies with full-time mothers in their first year are at an advantage intellectually and emotionally.’

‘It depends which research report you read,’ says Hattie, ‘and sorry about this, but I do tend to believe the ones that suit me. She’ll be fine. We’re living on nothing, I have to ask you for money as if I were a child, we are unable to pay the community charge so I have no choice but to use child-care for Kitty. You’ve already told me I’m mad. What use is it to Kitty to have a mad mother?’

‘You’re being childish,’ says Martyn, with some truth. ‘And “mad” is not a very helpful word to use. Let’s say you have been a little disturbed lately. But what’s the point of my saying anything; you’ve jumped ahead and taken my approval for granted.’

He slams the fridge door a little harder than is necessary or desirable. Indeed, so hard does he slam the door, that the floor shakes and in the next room baby Kitty stirs and lets out a cry, before fortunately falling asleep again.

One of the unspoken rules of engagement in the battle for the moral high ground waged so assiduously by Hattie and Martyn is that the weapons of bad temper – bangings, crashings and shoutings – should not be used.

‘Sorry,’ he says now. ‘I haven’t had all that brilliant a day. I know I’ve more or less turned over Kitty’s care to you, and I’d so much hoped we could do fifty-fifty parenting, but that’s because I have to, not because I want to. All the same, you could at least have called me at the office and warned me.’ ‘I didn’t want Agnieszka to get away,’ says Hattie. ‘Someone like her can pick and choose. As a fully qualified nanny in Kensington she could get £500 a week and her own maid.’ ‘That is revolting,’ says Martyn.

‘But she wouldn’t be happy doing that. She’s a real homebody, Babs says. She prefers to live as family, work in a real home, halfway between au pair and nanny.’

‘She’d better make up her mind,’ says Martyn. ‘Au pairs are covered by strict guidelines: nannies are not.’

‘We’ll sort that out when the time comes,’ says Hattie. ‘I took to her on the phone. You can tell so much from people’s voices. Babs says she’s exactly right for us. She got such a good reference from Alice that Alastair said it sounded as if Alice was trying to get rid of the girl.’

‘Ah, the Tory MP. And was she?’ asks Martyn.

‘Trying to get rid of her? Of course not,’ says Hattie. ‘Alastair was joking.’

‘Funny sort of joke,’ says Martyn.

Martyn is still cross. His blood sugar is low after a day in the office. Obviously he is right; it is not ethical to exploit another in this way, especially if they have little power in the labour market, but it would be kinder to everyone if he left the matter alone.

He can find precious little in the fridge. Since Hattie took maternity leave they have not been able to afford dinners out, take-aways or luxuries from the delicatessen. Supper tends to be chops if he’s lucky, with potatoes and vegetables and that’s it, and served in Hattie’s own good time, not his. He finds some cheese in the salad drawer and nibbles at it, but it is very hard. Hattie says she is saving it for grating.

Martyn feels Hattie rather overdoes what he refers to as her ‘frugal number’. Anything will do at the moment to make life bleaker for both of them. She hates spending money on food. Food is full of pollutants which if she eats might end up in Kitty via the breast milk. Since the birth, it seems to Martyn, Hattie has gone into rejection mode. Sex also has become a rare event – rather than the four or five lively times a week it used to be. He can see it might be a good idea if she did go back to work, but he does not like her organising their joint life behind his back. He is Kitty’s parent too.

Frances Presents Some Authorial Background (#ulink_0e887b42-4c10-5023-8386-1f6b9517a044)

Let me make clear who is speaking here, who it is who tells the tale of Hattie, Martyn and Agnieszka, reading their thoughts and judging their actions, offering them up for inspection. It is I, Frances Watt, aged seventy-two, née Hallsey-Coe, previously I think, but for a short time, Hammer: previously Lady Spargrove: previously – we would have got married but he died – O’Brien. I am Lallie’s bad mother, Hattie’s good grandmother – determined to get my money’s worth from my new laptop, bought for me by my sister Serena. Write, write, write I go, just like my sister. ‘Scribble, scribble!’ As the Duke of Gloucester said to Edward Gibbon, on receiving The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, a million and a half words long: ‘Always scribble, scribble, scribble! Eh! Mr Gibbon?’

Serena is the one with the reputation for writing: she has been writing steadily since she was thirty-odd, scarcely giving herself a minute’s time for reflection: she pays everyone – the household helps, the secretaries, taxi drivers, accountants, lawyers, the Inland Revenue, friends, grocers – just to make them go away so she can get on and write. But this doesn’t mean she has a monopoly on writing skill. I myself have finally found the time and courage to do it, while my husband Sebastian is in prison. The presence of a man in the house can be inhibiting to any endeavour which does not include him, such as writing a book. I run a little art gallery in Bath, but I choose not to open every day, so I have time and to spare.

Hattie, beloved only child of my only daughter Lallie, called me this evening to say she was going back to work, and had found an au pair for her baby, and Martyn was being a bit iffy about it. Is her return to work a good thing or not? What can I say? Speaking as the great-grandmother she has made me, she should sacrifice her life to the baby. Speaking as her grandmother, I want her to get back into the world and live a little and have affairs with men – life is for living, not just handing on. I am actually very fond of Martyn, but so far as I know he is only the second man she has been to bed with, and that does seem to me to be rather limiting.

Hattie will not settle easily to domesticity, that I do know. The Victorians used to pity girls like her, born too clever for their own good, never content as appendages to the Male – daughter, mother, sister, wife – forever striving for an identity which was theirs and theirs alone, whilst living in a society which forbade them to find it. Such girls made bad mothers and worse wives. That was the old world wisdom.

Martyn, I know, has romantic ideas about having a full-time wife and mother for his child, but I know he is being unrealistic. Couples today need two incomes to get by. And Hattie is bound to pay the new girl too much: she has her great-aunt Serena’s generosity but not the means to fund it. The guiltier the mother, the higher the au pair’s wages – or else it goes the other way and the mother, identifying, is furious that the girl expects any salary at all, let alone any free time, let alone boyfriends in the house. But Hattie will be the concerned kind, and that can come expensive.

My grand-daughter Hattie is thirty-three. She has a sharp nose, a square jaw, and a mass of striking red-gold Pre-Raphaelite hair, curly on some days, frizzy on others, which she keeps in a cloud around her face. I have the same hair, but mine has gone rather satisfactorily all-over white. It too is striking, and suits me. Hattie has very long legs: this she must get from her father, since her mother Lallie’s are rather short and plump of calf. Not that anyone has seen Bengt’s legs, other than Lallie (presumably) briefly, once, long ago and far away when Hattie was conceived. Lallie is a pouting, fleshy, sensuous beauty with a high colour, very different from her daughter’s lean, high-cheekboned, abstemious, long-fingered paleness. You would think from the look of them that the daughter, not the mother, would achieve world fame playing the flute but it is the other way round.

Hattie has what her great-aunt Serena calls ‘good bones’ and men can be guaranteed to turn and stare at her when she walks into a room: amazing what confidence this can give to a girl. But she is currently thin to the point of gauntness. The strain of looking after a new baby has told on her. Or perhaps it just is that some women do get pale and thin after having babies, just as some stay with the rounded pinkness of a good pregnancy. The body is wilful and usually goes the way a person very much hopes it won’t.

The trick with bodies, as with so much in life, is not to let the Fates know just how desperate you are about anything. You must look casual and act casually, play Grandmother’s Footsteps with life. Hattie and the cousins used to play it at Caldicott Square. One child stands in front of the group with her back turned. The others move forward stealthily. The one in front turns swiftly. Anyone who’s caught moving or giggling is out, and has to leave the game. So don’t move; don’t giggle; don’t show the Fates you care, and the less likely you are to develop a cold sore before the wedding, tonsillitis before the holiday, thrush before the dance, and your period won’t come on as you’re putting on your tennis skirt.

Hattie is really happy to be thinner than she was, but placates the Fates by saying aloud she doesn’t mind what size she is so long as she and Kitty are happy and healthy. Martyn – she likes to add – is certainly not one of those men who would be put off by a few extra pounds.

Likewise, Hattie does not show how she looks forward to going back to work, but murmurs to others that she might have to start earning again, since it’s such a problem managing on one salary. These sops thrown to destiny are working for the moment: she has got thin by sheer force of secret yearning, a job is waiting for her and now a kindly destiny has put Agnieszka her way. Hattie loves little Kitty, of course she does. Indeed, she is sometimes quite overwhelmed by love, and presses her face against the baby’s firm, soft, milky flesh, and thinks that is all she needs in life; but of course it is not. It’s just so dull at home. You listen to the radio, and struggle to stem a sea of disorder – the trouble with babies is that it’s all emergency: you keep having to stop whatever you’re doing. She craves gossip, infighting, the amphetamine effect of deadlines, and the swirling soap opera of office life. She misses conversation as much as her salary. Kitty lies around gurgling and disgorging the food that’s put into her and is not a valid source of entertainment, only of love, received and given. Songs and scriptures tell her that love is all she needs, but it is not true. Love is all she needs just for some of the time. So Martyn is being ‘a bit iffy’. I can imagine.

A Bit Iffy (#ulink_ebe8783d-11dc-5610-aa12-96ead191e555)

‘But Hattie,’ says Martyn, ‘we have a problem here.’

‘What’s that?’ Hattie asks.

‘Just how ethical is it to ask another woman to look after one’s child? Perhaps using child-care is in itself exploitative.

I know it’s convenient but is it right?’

‘It’s always been done,’ says Hattie, allowing a hint of irritation to enter her voice. ‘Those with the best education get the most money. I use my skills to earn: she uses her human instincts to earn. There are more women like her than there are women like me, so we get them to look after our babies.’

‘But in an equitable society,’ says Martyn, ‘the scale would be reversed and we would be paid to make up for the pain of our work, not rewarded for the pleasure we take in it.’

‘It isn’t an equitable society,’ says Hattie. ‘That’s it.’

‘You are so argumentative,’ he complains. But he is pleased at the return of her spirit.

Soon she may be back to normal, and their diet will improve. But he’s not finished yet.

‘We both agree that raising a child is the most important thing anyone can do, and it should be paid concomitantly.

And a nursery is probably the best option if you don’t want to look after your own child.’

But Hattie has won, and his voice fades away and she gives him a half kiss, half nibble on his ear to show there are no hard feelings. If there is to be better food in the fridge Hattie must go out to work, and when it comes to it Martyn would rather that his child was looked after in the home than be sent to a nursery. He has not liked to ask what age Agnieszka is, nor whether she will be a pleasure to look at or otherwise. He is above such enquiry. He has a stereotyped Polish girl in his head: she is pale, thin, high-cheekboned, small-breasted, attractive but out of bounds.

Hattie has it all arranged. Agnieszka is to live in. This unknown and untested person is to have the spare room, look after the baby as a priority and do such domestic work, cooking and laundry that she can find time to do: she is to have Saturday and Sunday off and three evenings a week to go to evening class. She will be paid a generous £200 a week, with of course full board and lodging. Babs, who is accustomed to employing staff, has been consulted on these matters and this is what she recommends.

Martyn points out that Hattie will have to earn at least £300 a week to break even on the deal – perhaps more if the girl is a big eater. Hattie says she will be paid £36,000 a year and Martyn complains that that is ridiculously low: Hattie explains that instead of taking statutory maternity leave she actually handed in her notice, so certain was she that she would never want to return to work, and though she expects rapid promotion, she will formally have to start work fairly low down the end of the pay scale.

‘With any luck,’ says Martyn, ‘this Agnieszka will be anorexic. That will save money on food. But hey, if she’s what you want, go ahead. Let’s share our evenings and our lives with a stranger. So be it. Only do be sure to ask for written references.’

Martyn loves Hattie. Dissension is just part of their life. He loves brushing up against her in the kitchen; he loves the warm roundness of her body, so different from his own angularity. He loves the ease of her conversation, her ready laugh, her lack of doubt, the way she didn’t hesitate when she found she was pregnant and just sighed and said it was fate, why fight it?

Martyn comes from an awkward, belligerent family who look for slights and insults and find them, and would root out an unwanted baby without a second thought. He had no idea, when he met Hattie at a peace demo, that people could be like this, that sheer affluence of good feeling, not a superfluity of rage, could drive them on the streets in protest. It was a destined encounter. Surging crowds pushed them into each other’s arms in an alley behind Centre Point. He had an erection, and deeply embarrassed, blushed and apologised when it would have been more fitting to overlook the matter, pretend it had never happened. She said, ‘Not at all, I take it as a compliment.’

In three weeks he had moved in with her, and now they have a house and a baby. He would like to marry her but she won’t do it. She says she has no respect for the institution, as indeed neither does he, at least in principle. Both look at marriages within their immediate families and decide it is not for them. The complexity of divorce, and also its likelihood, alarms them both. But he has less objection to being owned by her, than she does by him. That worries him. He loves her more than she loves him.

‘What’s for supper?’ asks Martyn, having abandoned any hope of finding something edible in the fridge, kissing the back of her neck, melting her wrath at once.

‘I must finish the ironing first,’ says Hattie. Her mother Lallie has hardly used an iron all her life long. It can hardly be in the genes. But then Lallie’s a creative artist and Hattie is avowedly not, and so the daughter must take the normal route to a satisfactory environment, not by filling the air with music, but by providing an easy background for others.

All the same Hattie stops ironing. She needs little incentive. She bought pure cotton, wool and linen fabrics, natural fibres dyed with organic dyes, to cover the baby’s back. Now she regrets it. Unnatural fibres dry faster than natural, don’t matt, shrink or discolour with washing. They were developed for very good reason. The cot is always damp because ecologically-sound terry nappies are less effective than disposable ones. It doesn’t make much difference to the baby what fabrics it regurgitates over. But Hattie is stuck with what she committed to, if only by virtue of the cost of replacement, and she does like things to look nice. There are still some few items left to iron but when were there ever not? Martyn may feel less stressed if he eats. She is not hungry herself. She opens a can of tuna and a jar of mayonnaise and heats up some frozen peas. Martyn once, rashly, said how much he liked frozen peas.

‘Babs and I will be in adjacent offices,’ she says, as the peas come to the boil and bob about at the top of the pan. ‘And we’ll be able to share a taxi home.’

‘A taxi!’ says Martyn. ‘If we’re to afford an au pair there won’t be much taking of taxis anywhere.’

He knows tuna is nutritious and with bread and peas makes a balanced meal, but that doesn’t mean the tinned fish doesn’t clog up the mouth. The peas are not even bright green petits pois (too expensive) but large, tough and pale green. The bread is sliced brown Hovis. In his mother’s household, meals were frequent, generous and on time, no matter how paranoiac and backbiting those who sat around the table were. The bread was fresh, crusty and white. But now in his own home the very concept of ‘meals’ has been abandoned. Since Kitty’s birth he and Hattie eat to assuage hunger, and the desire seldom strikes them simultaneously. Yes, it is time she went back to work.

Demotic Credentials (#ulink_683e100d-8984-5a89-9dac-3a0c2d1c3450)

‘Hattie,’ I say, ‘what I think about you going back to work or not going back to work is irrelevant. You will do what you will do, as ever.’

‘But I do like to have your permission, Great-Nan,’ she says. I know she does. It touches me but I have asked her not to call me Great-Nan. ‘Grandmother’ is best, ‘Gran’ will do, ‘Nan’ is vulgar and ‘Great-Nan’ ludicrous, but Hattie will do what she will do.

Since Kitty came along, she claims her right to set me yet more firmly in the past and advance me a generation in public disesteem. She called me Grandmother in a perfectly proper way until she met Martyn, after which she took to calling me Nan, presumably out of loyalty to her partner’s demotic origins. To possess a father who died in an electricians’ strike is a rare qualification in the political media circles in which Martyn works. Anyone who does may feel the urge to make the most of it. Grandmother or even Granny smacks of the middle class, and the young these days are desperate to be seen to belong to the workers.

But I daresay next time she sees me she will hold Kitty out to me and say, ‘Smile at Great-Nan,’ and the infant will bare its toothless gums at me, and I will smile back and be delighted. I am totally dedicated to my family, and to Hattie, and to Kitty, and even to Martyn though he is not always a bundle of laughs, but then neither is Hattie, certainly not since they had the baby.

Martyn is tall, over six foot, solidly built, sandy-haired, and hollow-cheeked but otherwise attractive enough. Girls like him. He has a First in politics and economics from Keele University, and is a member of Mensa. He tried to get Hattie to join but she declined, finding something distasteful about setting herself above others, intellectually. This may be because her mother also once belonged to Mensa, having joined in the days when you could send the qualifying questionnaire by post, so you could get your friends to supply the answers. Martyn has worn glasses since he was five. His shoulders are slightly rounded, from bending over so many computers, so many textbooks, so many reports and evaluations.

His mother Gloria, forty-three years old when Martyn was born, the youngest of five, had the same big-boned build, making twice of Martyn’s father Jack. The latter was slightly built, although like his son sandy-haired and hollow-cheeked. But Martyn looks healthy. Jack never did, certainly not by contemporary standards. Chip butties, fried fish, mushy peas and sixty cigarettes a day made sure that his arteries were clogged and his lungs black-lined. It was surprising he lasted as long as did. Gloria is still alive and in a nursing home in Tyneside. Martyn and Hattie visit her twice a year, but neither looks forward to the visits. She finds Hattie too fancy and strange-looking. The other siblings live closer to their mother, and visit more often.

Martyn is the only one who went to university. The others could have, but chose not to. They were like that: so sharp they cut themselves. Their father, Jack, joined the Communist Party as a boy in 1946, leaving when Russia invaded Hungary in 1968 to become a less extreme labour activist, but fighting as ever for the rights of the working class. He died of a heart attack when on the picket line during a strike. Waste of a good death, his friends said, better had it been from police brutality. Jack’s hair thinned and went in his thirties.

Martyn fears that the same thing will happen to him: he hates to see hairs in his comb when he gets to the mirror in the morning. The bathroom is small, and usually hung with wet, environmentally-friendly, slow-drying garments.

My own demotic credentials are rather good, these days. My husband Sebastian is in a Dutch prison serving a threeyear sentence for drug running. His name works against him. It is too posh. It attracts attention. I have suggested he calls himself Frank or Bill, but people are oddly loyal to the names that their parents gave them, as Hattie has observed to Martyn in relation to Agnieszka. Sebastian was, I believe but do not know, trying to supply the Glastonbury Festival with Ecstasy in yet another doomed attempt to solve our financial problems. These of course have become much worse as a result, but there are consolations. I have my new computer and a novel I can write in peace. I can sleep in all the bed, not a third of it; I can listen to the radio all I want, and now the panic fear, the anxiety as to how Sebastian is faring, and my own sense of social disgrace have faded, I can almost call myself happy. In other words, one can get used to anything.

And it’s surprising, even at my age, how suitors cluster round as soon as the man of the house is away. The newly divorced woman, the grass widow and the prison widow are as honey to the wasps of the passing male, in particular the best friends’ husbands. If there is no man to begin with, the attraction is not so great. Men want what other men have, not what they can have for the asking. So the lonely stay lonely, and the popular stay popular; the leap from one to the other is hard but not impossible. True widows do all right if they have come in to a great deal of life insurance. But otherwise their lot is hard: a grave too new for a headstone is disconcerting, and once it’s up it’s worse. Lose one husband, lose another. But the grass widow is in a good position, the promise of a short-term exercise in love and desire with a finite end is tempting. Age has little to do with it, in these days when a man of sixty seems old and a woman of sixty seems young. So I have suitors who do not interest me – they include a retired Professor of Philology from Nottingham, an art student who mistakenly thinks I have money and ‘likes older women’, and a television dramatist of the old school, largely unemployed, who thinks a connection with Serena would be a good idea. But like Penelope I encourage the suitors so far, and no further. I have no real intention of betraying Sebastian. I love him, in the old-fashioned, critical, but steadfast manner of my generation, we who loved first and thought afterwards. ‘Men have died from time to time, and worms have eaten them, but not for love,’ said Shakespeare, and that is true for women too today, if not for the women of my generation. We lot died for love, all right.

‘How am I really?’ I respond to Hattie’s question. ‘How I am really is angry with Sebastian.’

‘Oh, don’t be,’ she says, ‘I am sure he is suffering enough.’ ‘I am suffering too,’ I say, ‘I have suitors. But I must say I am faltering in my Penelope role. Three years is a long time.’ ‘Oh, don’t!’ she implores. ‘Just give up and behave like a grandmother and wait.’

‘He should have looked behind him,’ I say. ‘A police car followed them for forty miles and they didn’t even bother to look behind. In a car packed with illegal drugs!’

‘Perhaps he didn’t know they were in there. And he wasn’t driving.’

‘Oh, come off it,’ I say. ‘Don’t you start excusing him too.

Last time I saw him he said, “I did it for you.” That made me really cross. He committed the crime, not me.’

Hattie laughs and says it’s true, men have a knack of making their womenfolk responsible for everything that goes wrong. Martyn will open the front door and turn to her and say ‘but it’s raining’ as if it were her fault.

Sebastian is my third husband, fourth if I include Curran, so I like to think I have some knowledge of the ways of men, in the house and out of it. I regale her with tales of husbands who pat their pot bellies and smile and tell you it’s your fault because your cooking is so good, blame you for their adulteries (your fault I slept with her: you were too cold, snored too loudly, not there enough – anything). Your fault I lost my job, you did not iron my shirts. Your fault I am in prison, I did it for you. Serena’s previous husband George gave up painting pictures and in future years was of course to blame Serena for failing to dissuade him from doing so. You should never try to make a man do anything, Serena says, that he doesn’t want to. It always bounces back to you.

I love you, I love you, is the mating cry of the arriving male. All your fault, as he departs.

I met and married Sebastian when I was thirty-eight: he was forty. We had no children together: he had two by an earlier marriage: I had accumulated two along the way. I can only hope that imprisonment will not have the same effect on Sebastian as the heart attack had on George: that he will not, like George, encounter some therapist who will encourage him in the belief that it’s all the wife’s fault and the only way to survive is to leave her. To break the ties that bind. It is a fairly absurd worry. Fortunately counsellors are in short supply in Dutch prisons.

‘Codswallop,’ I say to my grand-daughter, ‘Sebastian just wanted some excitement.’ But I tell her I am only joking about the suitors, I will wait patiently for my husband’s return, and I will.

Miraculously, we have managed to keep Sebastian’s conviction from the press. He is Serena’s brother-in-law, and as such could attract attention. And though I tell her publicity is good for sales, she says she is never sure of that; the more people know about your feet of clay, the less they want to buy your books and she certainly does not want to be pitied on account of a feckless brother-in-law. At seventy-three she is still working – novels, plays, occasional journalism – if you are self-employed there is always last year’s tax to be paid.

When Sebastian went inside, Serena paid off our mortgage, so I can just about manage the bills. A small amount comes in from the gallery; in these days of conceptual art normal people still buy paintings in frames. Serena flies Club Class on a scheduled flight to Amsterdam every six weeks or so to visit Sebastian: Cranmer, her much younger husband – though at fifty-five he’s scarcely a toyboy – or some other family member goes with her. As a family we give each other what support we can. I mostly go on my own, on easyJet from Bristol airport at a quarter the cost.

I can feel Martyn in the background, thinking Hattie has been on the phone too long, chattering, and wanting her to pay more attention to him. His family don’t chatter, as Hattie’s does. I hear him putting on the radio in the background, clomping about. Well, why should he not? When the man works and earns and the woman does not, it is only meet and fitting that his interests should take precedence over hers. ‘I’d better go,’ I say. ‘Bless you for calling. I’m just fine and I think you should go back to work.’

‘Thanks for your permission, Gran,’ she says, but stays on the line. ‘Don’t worry about Sebastian; he’ll be all right. He has his art to keep him warm. I remember Great-Gran saying in the middle of the trial, just before she died, that at least prisons were comparatively draught-free. He should think himself lucky.’

Hattie’s great-grandmother Wanda had three daughters: Susan, Serena and Frances the youngest, that is to say myself. And Frances gave birth to Lallie, and Lallie gave birth to Hattie, and Hattie gave birth to Kitty. Wanda died the day Sebastian was sentenced to his three years – leaving her descendants, though distraught at her loss, at least now with time and energy to go prison visiting. I do not say she timed her death for Sebastian’s benefit, but it would not have been out of character if she had. She brought us up to be dutiful and attentive to family responsibilities at whatever cost to ourselves. Susan, our eldest sister, died of cancer in her late thirties. My mother was a stoical person, but ever since then, she complained, she felt the cold. Draughts loomed large in her later life.

Hattie has not been to visit Sebastian in prison, though she always asks after him, and writes. Well, she has been pregnant and now she has a small baby, and though of course he has not said so, Martyn would feel easier if she did not go. He has his position at the magazine to think about, and his political ambitions. He hopes to stand for Parliament at the next election, and does not want his position compromised by a step-grandfather in prison.

‘All right, darling,’ she says to Martyn. ‘I’m just coming. I think I left the car key under the nappies.’ And she says good-bye to me and is gone.

Sebastian In Prison (#ulink_b609aa11-54f1-5140-94bd-7052b6ac2f4e)

Sebastian is allowed two visitors once a week, if all goes smoothly at the Bijlmer prison, and so far it has. The authorities encourage him to paint. They changed his cell so that he could stand an easel up in it. They like their prisoners to be creative. They can hang his paintings on the walls of that bleak place. He is, after all, a Royal Academician. He cooks excellent curries for other prisoners in his block. No one has raped him or even sworn at him. The wardens address him as Mr Watt. Even so, the Bijlmer is a horrible, frightening, noisy, clanging, terrible place, but villains are villains only some of the time and if you are careful to be out of their way when they are in violent criminal mode, you can get by. So Sebastian tells us.

But I want him home where he’s safe, and can hear birdsong. I try not to think of him too much. He paints in oils: the house still smells of them, though the turps is drying up in the jam jars and the brushes stiffening: sometimes I catch a movement out of the corner of my eye and see what can only be his shadow through the open door of the attic. I never knew before now that the living could haunt a place. But Sebastian manages. It’s a kind of company but I would rather have the real thing. Sebastian became an RA twenty-five years ago; he had his name in the gossip columns and an exhibition at the Marlborough Gallery. He was once a member of the Arts Council, but no longer. He went on painting landscapes in frames long after everyone else had stopped. He is an idealist and a romantic. This is why he is in trouble.

Sebastian believes in the right of the artist to live in whatever state of mind they choose, natural or one that is chemically induced, drugs also being God-given. In the same way, he tells me, that women with pale lips choose to use lipstick to make them brighter. He denies the right of Government to deny choice to the individual. He is perfectly intelligent in other ways, and indeed charming, but he does not hear me when I say, in my mother Wanda’s voice, that a principle so convenient can hardly be counted as a principle, it is too laced with self-interest.

Sebastian, after the manner of men, tends to be deaf to uncomfortable truths. He believes himself to be a favourite of the God who gave him his artistic gift. His defence lawyer described him as paraphrenic – a person sane in all respects except one. His capacity for trust is pathological. He would meet up with his criminal associates in the Royal Academy restaurant, thinking that was perfect cover, though the ladies up from the provinces would look askance over their quiche and the white wine at the expensive, flashy suits and talk knowingly about ‘bling’. When he was in Holland and fingered by these friends of his, Sebastian was the only one surprised. That is my reading of the situation. He never told me the detail. He was ashamed.

A Further Ethical Discussion After Supper (#ulink_6764ee65-c2fc-5a7c-938b-32baa8aaef74)

‘With your Swedish background,’ says Martyn to Hattie, ‘I am surprised you take the view you do.’ He will not let up. He is no longer hungry but he is unsatisfied, and deprived of sensual pleasures. Baby Kitty still sleeps in a cot next to their bed. Martyn can see the sense of it, but wishes the baby slept in a separate room. Sometimes he wakes in the night and reaches out for his wife, which seems his natural right, and finds Hattie sitting up and feeding Kitty. (He knows she is not his wife but his partner, and thus ‘natural right’ is the more questionable: it is one of the subliminal reasons why he would marry her if he could.)

Hattie will look at the child with what Martyn hopes is adoration, but suspects it is something more like amazement. She feels uneasy about making love while dripping milk from her breasts. For someone who rather dislikes the thought of breast-feeding – so cowlike – she produces a remarkable amount of this sweetish, delicately scented liquid from her nipples. Martyn, too, is amazed. It puts him in mind of a film he saw as a child about the exploitation of workers in the Malaysian rubber plantations. Cuts were made in bark and a strange yellowish goo would seep out. He was revolted. He knows breast-feeding is natural and right but he wishes Kitty fed from a bottle. He preferred it when Hattie’s breasts were erotic signifiers rather than dedicated to feeding another, even though that other has sprung from his seed. Indeed, Martyn finds the processes of parturition so bizarre as to be almost beyond belief.

Since the birth, he, who was once so scientifically reluctant and talked about Nature in the same way as people once talked about God – as the source of all goodness – finds himself all for cloning, test tubes, stem cell research, artificial wombs, GM crops and the like. The further from Nature and the more subject to intelligence and contrivance, the better. It has crossed his mind that an au pair would take up the spare room, and that this postpones the baby having a room of its own, and makes the likelihood of any decent, noisy, bounce-around-the-house sex even more remote than before.

‘What has my Swedish father got to do with anything?’ asks Hattie. Martyn points out that a Swedish Prime Minister’s wife, a full-time working lawyer, was lately in trouble for employing a maid to clean their house. That she should do so was seen as demeaning to her, her husband and the maid. In Sweden, people are expected to clean up after themselves.

‘Now we, who are meant to be working for the New Jerusalem, are to have a servant?’ Martyn asks, ‘Where are our principles?’

Hattie almost giggles. Sometimes she thinks he is addressing a public meeting, not her, but he has a future as a politician so she forgives him: he has to get into practice.

‘She’s not a servant,’ says Hattie, firmly. ‘She is an au pair.

Or a nanny. I don’t know which she will prefer to be called.’ ‘Whatever – she will be doing our dirty work because we can afford to have her do it, and she can’t afford not to do it,’ says Martyn. ‘What’s that if not a servant? Get real, Hattie. By all means do what’s convenient, but understand what you’re doing.’

‘We are embarking on a fair and sensible division of labour,’ says Hattie haughtily, seeing that mirth will not distract him.

‘Have you thought about the consequences of being an employer?’ Martyn asks. ‘Are we doing it officially, paying for insurance stamps, taking tax at source and so on? I certainly hope so.’

‘If she’s working part-time and lives in, she doesn’t need stamps,’ says Hattie. ‘She counts as one of the family. I asked Babs.’

‘I assume you’ve seen her visa, and she’s entitled to be in this country?’

‘Agnieszka doesn’t need a visa. She’s from Poland,’ says Hattie. ‘We’re all Europeans now. We must be hospitable and do everything we can to make her welcome. It’s all rather exciting.’

She has a vague idea of Agnieszka as a simple farm girl, from a backward country, with a poor education, but welltrained by her mother in the traditional domestic arts. Hattie will be able to teach her, and enlighten her, and show her how forward-thinking people live.

‘I wouldn’t be too sure,’ says Martyn. ‘She’ll probably hate it here and leave within the week anyway.’

Both come from long lines of arguers and defenders of principle in the face of all opposition.

To The Left! (#ulink_67705bfc-d1b3-5c61-9227-e38cffb06b0a)

In 1897 Kitty’s great-great-great-great-grandfather, a musician, joined forces with Havelock Ellis the sexologist and wrote to the Archbishop of Canterbury urging him to acknowledge the entitlement of young women to free sex. He forthwith lost his job as Director of the Royal Academy of Music, and had to flee to San Francisco, but it was a sacrifice gladly made in the interest of early feminism and the onward march of humanity.

Kitty’s great-great-great-grandfather, a popular writer, went to the Soviet Union in the mid-thirties and came back to report a socialist and artistic paradise. Thereafter there was no stopping the left-footed march of the family, certainly on the female side.

When the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament began, Kitty’s great-great-grandmother Wanda walked from Aldermaston to London, her daughters Susan, Serena and Frances at her side. In 1968, Serena’s second husband George was arrested for his part in the Grosvenor Square demonstration against the Vietnam War. In the seventies Serena’s boys Oliver and Christopher put on balaclavas and threw aniseed balls over walls to distract guard dogs – though I can’t remember what that was about. Serena and George housed an anti-apartheid activist in their house in Caldicott Square. Susan’s children and grandchildren still turn up to march against the war in Iraq. It’s in the blood. Even Lallie signs petitions to save veal calves from export. Hattie has demonstrated against GM crops – that was probably the time she and Martyn met crammed up against one another in an alley. One way and another it is amazing that the world is not yet perfect. The forces of reaction must be strong indeed not to fall in the face of so much good feeling and hope for the future, over so many generations.

From Kitty’s father comes a different strain, a more orderly, stubborn, self-righteous kind of gene: oppressed and poor, the family rise up to demand their rights. Martyn, educated and sustained by the kindly State they have brought about, works as a commissioning editor for Devolution, a philosophical and cultural monthly. It runs articles about plenary targets, enablement, and the statistics of State control. These days Martyn feels he has the opportunity to change the world from the inside out, and no longer needs to go on demos, which are only for those who don’t know the inner story, as he does. He too is certain that he is helping the world towards a better future.

I wonder what Kitty will do with her life? If she takes after her father’s side, she will end up working for some NGO, I daresay, looking after the asbestos miners of Limpopo. If she favours her mother’s side, and all the mess and mayhem attendant on their particular talents, she will be a musician, a writer, a painter, or even a protesting playwright. You may think I’m obsessive about the gene thing, but I have watched it work out over generations. We are the sum of our ancestors and there is no escape. Baby Kitty looks at me with pre-conditioned eyes, even as she holds out her little arms and smiles.

Acceptance (#ulink_86dff24f-7c1c-5709-be85-fe3d2d4e3464)

Martyn cheers up, for no apparent reason, rolls the name around his tongue, and likes it. ‘Agnyeshh-kah,’ he says, savouring the syllables. ‘I suppose it is less gloomy than Agnes. And you’re quite right. It’s antisocial to have a room going spare at a time when there’s such a pressure upon housing. Tell you what, Hattie, I’m still hungry. Supposing I get some fish-and-chips?’

Hattie looks at him in no little alarm. Hasn’t he just eaten? Can he still be hungry? Is this why he wants the car keys? To buy fish and chips? A dozen thoughts flow through her mind, oddly disorganised. Fish fried in batter is unhealthy on many counts, not just for the individual but for the planet. Re-used oil has carcinogenic properties. The batter itself is fattening. The wheat used, unless organic, will have been sprayed many times with toxic chemicals. Batter can be removed before eating, true, but the seas are being denuded of fish and good citizens are cutting down on their consumption. And isn’t there something about dolphins? Don’t they get caught in the trawler nets and die horribly? Hattie seems to remember that though dolphins occasionally save swimmers from sharks, they also get a bad press these days: apparently the young males chase and gang-rape the females. On the other hand Martyn has often said that fish and chips remind him of his childhood in Newcastle and doesn’t she love him and want him to be happy?

‘You could get an Indian, I suppose,’ she concedes. ‘Though the District Nurse is against curry. It gets through into Kitty’s milk.’

From time to time Martyn goes into what Hattie calls ‘shaggy mode’: his sandy hair sticks up, the skin on his face seems too loose for its bones, his eyes are too large for their sockets. It happens when he is in despair but doesn’t know it. At such times Hattie feels both great affection and pity for him. She capitulates.

‘Oh all right,’ she says, ‘go out and get us some fish and chips.’

Agnieszka Comes Into Hattie’s Home (#ulink_8c9ab701-54b2-5006-a3bd-fde89605e4b2)

A week later and Agnieszka rings the doorbell of the little terrace house at 26 Pentridge Road. Hers are strong, practical hands, the skin rather blotchy and loose and much lined upon the palm. They are not her best feature. She is in her late twenties and wears a brown suede jacket, a knee-length black skirt and a white blouse. Her face is pleasant, broad, high-cheekboned, her demeanour quiet and restrained, her hair cut in a neat, thick, brown-to-mouse bob. Apart from the slightly sensuous air imparted by the short, full upper lip she seems to present no danger to marital harmony. She is far too serious for sexual hanky-panky.

The doorbell needs attention. There is a loose connection somewhere and the buzzer seems in danger of giving up completely. Agnieszka does not ring a second time but waits patiently for the door to open. She hears the sound of infant wailing growing nearer and Hattie opens the door. Hattie’s hair is uncombed and she is still in a blue velvet dressing-gown, with dribbles of porridge down the front and what looks like infant vomit on the shoulder. It needs to go in the washing machine.

Agnieszka holds out her arms for the baby, and Hattie hands the child over. Kitty is taken aback and stops crying, other than for a few more gulping sobs while she gets her breath back. She looks at Agnieszka and smiles divinely, revealing a tiny little pink tooth which Hattie sees for the first time. A tooth! A tooth! Agnieszka wraps the child more securely in its blanket and hands Hattie her bag to hold. Hattie takes it. It is a capacious black leather bag, old but well polished. Hattie thinks perhaps Kitty won’t like having her limbs constrained but Kitty doesn’t seem to mind. Indeed, Kitty exhales a deep breath of relief as if she had at last found her proper home, closes her eyes and goes to sleep.

Agnieszka follows Hattie through into the living room, and lays the baby on its side in the crib. She folds crumpled baby blankets neatly, holding them against her cheek to test for dampness, putting those that pass the test over the edge of the crib and gathering up the damp ones. ‘Where do we keep the laundry basket?’ she asks. Hattie stands gaping, and then points towards the bathroom. The ‘we’ is almost unendurably reassuring.

Hattie, dressing in the first-floor bedroom, catches a glimpse of Agnieszka in the landing bathroom, sorting the overflowing washing basket. Whites and coloureds, baby and non-baby. All get filed into plastic bags before being put back in the basket. Nothing overflows. Soiled nappies go into a covered pail.

Hattie remembers Martyn’s strictures about the necessity of checking references, but to do so would be insulting. She feels she is the one who should be giving references.

Agnieszka asks if she can see her room. Martyn has piled his suits onto the spare bed before setting out for work that morning, and Hattie has not yet found space for them elsewhere – she has had a bad morning with the baby. Agnieszka says she is satisfied with the accommodation, but perhaps she could have a small table to use as desk? Would Hattie like Kitty to sleep in her cot in the spare room with Agnieszka, or stay in the bedroom with her parents? She is sleeping through the night by now? Good. Then the former will be preferable, because then she, Agnieszka, can get Kitty up and dressed and having breakfast before Mr Martyn, as she already calls him, needs the bathroom. Early-morning routines are important, she says, if a household is to run smoothly. While Kitty sleeps she, Agnieszka, will get on with her studies.

Agnieszka now picks up and carries a chair to the front door, climbs on it, and does something to the wires that feed the bell. Hattie had never noticed those wires existed. It certainly has not occurred to her that the bell can be mended. Agnieszka tries the bell and lo! it rings firmly and clearly, no longer hesitant and hard to hear.

‘Don’t wake the baby,’ says Hattie. ‘Hush.’

‘It’s a good idea to get baby used to ordinary household sounds,’ says Agnieszka. ‘If Kitty knows what the sounds are about she won’t wake. Only unaccustomed noise wakes babies. I was told this in Lodz, where I studied child development for two years with the Ashoka Foundation, and it checks out.’

She gets down from the chair and replaces it in its original position, and takes the end of a damp cloth and removes a little wedge of encrusted baby food where it’s been stuck for some time.

Agnieszka tells Hattie that she is married to a screenwriter in Krakow, and plans to be a midwife, but must first perfect her English. Yes, it is difficult being away from her husband, whom she loves very much. She would like ten days off over the Christmas period to visit him, and her mother and her younger sister, who is not well. She is very close to her family. She produces photographs of all of them. The husband has a lean, dark, romantic face: the mother is dumpy and a little grim: the sister, who looks about sixteen, is fragile and sweet.

‘Ten days seems rather a short time,’ says Hattie. ‘Make it two weeks and we’ll manage somehow.’

Thus, without further argument or discussion, Agnieszka is engaged. But first she says she must put the damp washing into the machine. Plastic bags are invaluable for sorting laundry in an emergency, she says, but she will bring her own cotton ones for household use in future. Sorting prior to the wash makes sure mistakes are not made: white nappies do not pick up colour from black underpants, or cotton jerseys stretch in the boiling wash. Hattie might like to look into the local nappy laundry: this collection/delivery service can work out cheaper in electricity and soap powder than a home wash, and is less strain on the environment.

Still the baby sleeps, smiling gently. Hattie’s life slips into another, happier gear. While Agnieszka keeps an eye on the white wash – Agnieszka has put the machine on its ninetydegree cycle, she notices, something she, Hattie, never does in case the whole thing boils over and explodes, but Agnieszka is brave – she goes round the corner to the delicatessen, ignoring the common sense of the supermarket, and buys two large pots of their fake but convincing caviar, sour cream, blinis and champagne. She must stop being mean, rejecting and punishing. She can see this is what she has been doing. Not his fault the condom broke. She and Martyn will live happily ever after.

Frances Worries About Her Grand-daughter (#ulink_d96379f7-0d7a-5284-a7d6-c9e61821e0e1)

I hope Hattie understands the complexities of having an au pair in the house. For one thing Hattie is not married, only partnered, which in itself is rash. ‘Partnerships’ between men and women, as everyone knows, are more fragile even than certificated marriages, and the children of such unions likely to be left without two resident parents. Any disturbance to the delicate balance is unwise. If introducing a dog or a cat into a marriage can be difficult, how much more so a young woman? Some kind of female rivalry is bound to ensue. And if it all goes wrong the decisions are the more painful. Who takes the dog, who takes the cat, who takes the au pair when couples split? Forget the children.

Martyn is a good enough boy in his terrier fashion, never willing to let go, and as a couple they are affectionate – I have seen them go hand in hand – and he is a responsible father, having read any number of guide books to parenthood, but I am left with the feeling that he has not yet arrived at his final emotional destination, and neither has Hattie, and that makes me uneasy.

They have their shared political principles to fall back upon, of course, and I hope it helps them. I am an upright enough person myself and a socially conscious one, and in my youth, once the wild years were over, kept the company of kaftanclad hippie girlfriends and bearded boyfriends with flares and sang along with Joni Mitchell. There was a time when all the men one knew in the creative classes had Zapata moustaches: it is difficult to know what a person with such a moustache is thinking or feeling, which may be why they were so popular.

That was in the sixties when women and men hopped in and out of each other’s beds with alacrity, trusting to luck and the contraceptive pill to save them from the consequences of broken hearts and broken lives, and before venereal diseases (now called STDs to remove the sting and shame) put a blight on the whole enterprise – herpes, Aids, chlamydia and so on – but I never urgently sought after righteousness or thought the world could be much improved by the application of Marxist theory.

In any case I had too little time or energy left over from successive emotional, artistic and domestic crises to concern myself with political theory. The creative gene is strong in the Hallsey-Coe family, and we tend to marry others like us, so lives of quiet respectability amongst them are rare. We end up writers, painters, musicians, dancers – not metallurgists, marine biologists or solicitors. In other words we end up poor, not rich.

Hattie, a linguist and a girl of high principle and political awareness, is fortunate enough to be born without a creative spark in her, though this can sometimes flare up quite late, and there may yet be trouble ahead. Serena did not start writing until she was in her mid-thirties: Lallie on the other hand was an infant prodigy, performing a Mozart flute concerto for her school when she was ten.

The Effects Of Bricks And Mortar On Lives (#ulink_c0877ec3-4ee5-53ac-be9b-1f88e8374c2d)

Let me tell you more about Hattie’s and Martyn’s house. Houses are not neutral places. They are the sum of their past inhabitants. It is typical of the English of the aspiring classes that they prefer to live in old places rather than new. They crawl into someone else’s recently abandoned shell and then proceed to ignore whoever it was who went before. Tell them they’re behaving like hermit crabs, and they raise their eyebrows.

Pentridge Road was built towards the end of the nineteenth century, rooming houses for the working classes, few of whom ever grew to optimum size or lived beyond fifty-five. The young couple see themselves as somehow set apart from the heritage of bricks and mortar in which they live. They feel they have sprung into existence ready-formed and into a brand new world, blessed with more wisdom and sophistication than their predecessors. Tell them they inherit not only the genes of their forebears but the walls and ceilings of those socially and historically related, and they look at you blankly.

Some things do happen which are an improvement – facts are certainly easier to come by in the twenty-first century than in the age of the printed page. News of the outside world flows like chlorinated water from radio and television: houses are better warmed and food cupboards more easily filled, but those who live in them are as much as ever at the mercy of employers and whatever rules of current cultural etiquette apply, whether it’s the obligation to fear God or to own an iPod.

Tear off the old wallpaper – as Hattie and Martyn did when they bought the house – and find yellowed scraps of newspaper beneath – accounts of the Match Girls’ Strike, the force ten gale which brought down the Tay Bridge, the costumes worn at Edward VII’s coronation. Hattie and Martyn scrape them all ruthlessly into the bin, scarcely bothering to read. I think the otherness of the past disturbs them too much: they like everything new and fresh and startagain.

The plaster walls are painted cream, not papered dark green and brown, and the paint at least does not poison you with lead – though traffic pollution may serve you worse. But very little changes in essence. Other generations lay in this same room at night and stared at the same ceiling worrying what the next day held.

In my sister Serena’s solid early-Victorian house in a country town, the stone stairs from the basement are worn down in the middle from the tread of countless servants, up and down, up and down. You’d think their tired breath would haunt the place but it doesn’t seem to. Serena’s mother-in-law died in the room where Serena now has her office but the fact only very occasionally affects her, though she claims her ghost walks on Christmas Eve. That is to say she once saw the old lady cross the passage from spare room to bathroom, and looking twice there was no one there. Her mother-in-law left a benign presence behind her, Serena claims. When I say, ‘But I have seen the ghost of the living Sebastian in his studio,’ she does not want to believe me. She likes to be the only one in touch with the paranormal. She isn’t.

I live in a small farmhouse which has been a dwelling for the last thousand years at least. The hamlet, outside Corsham in Wiltshire, is mentioned in the Domesday Book. Its occupant would have been fairly low down the social scale: a sub-tenant perhaps. Originally it was a single room for family, animals and servants. Then an outside staircase was built and a couple of rooms above. The families moved upstairs, the servants and animals stayed below. Outhouses were built: animals were separated out from servants. The original barn was long ago converted to a dwelling. A studio was built out the back where Sebastian now paints, in ghostly form, and I hope will again, less spectrally.

Sometimes I wake in the middle of the night, seized by the fear that he will behave like an ageing man after a heart operation, and try to change his life, and the change will include separating out from those that love him. It happened to Serena and it could happen to me. In these wakeful nights the house creaks and groans and sighs, from sheer age or from the spirits of those who went before, including pigs, horses, sheep, servants, forget the masters and mistresses. Oh believe me, we are not alone. The central heating gurgles like a mad thing at night.

But back to the young, the loving, the breeding and the present, that is to say Hattie and Martyn. Martyn, to give him credit, is more conscious of the past than many, if only as a contrast to the benign Utopia he and his friends hope to achieve. Martyn has explained to Hattie, as she sits trapped in her nursing chair (an antique, which Serena bought her as a present) feeding Kitty, that the terrace house they live in – two up, two down – was designed for the wave of Irish navvies brought in to complete the earthworks for the great London stations which served the manufacturing North, the land of his roots. St Pancras, King’s Cross, Euston, Marylebone – every shovelful of earth and rock had to be moved by hand, and now forms Primrose Hill.

Hattie would like to live somewhere larger, even if less historical, but they cannot afford it and in any case, says Martyn, they should be grateful for what they have.

The navvies lived six to a room in what is now home for two grown-ups, one baby and now the maid. There is still an old coal fireplace in the top back bedroom where once, over coals scavenged from the King’s Cross mustering yards, meat and potatoes were cooked. A puny extension for the kitchen and bathroom was built in the 1930s and takes up nearly all the sunless yard. Agnieszka is to have the small back bedroom, next door to the one where currently Martyn, Hattie and Kitty sleep.

There is gas-fired central heating but the gas comes from under the North Sea and no longer from the coal mines. It’s cleaner, but it’s expensive and Martyn and Hattie dread the bills. Though at least everyone on the way from the oil rigs of the north to the man who reads the meter – or rather leaves his card and runs – is decently paid. Or so says Martyn. Martyn’s father, grandfather and great-grandfather fought for this prosperity and justice and achieved it. No one now who can’t afford a lottery ticket!

Martyn has recently been asked by his employers to write two articles explaining to a doubtful public that casinos are a good thing, bringing pleasure to the people, and he has, although he is not quite sure that he agrees. But he bites back argument as he writes. There is, as always, a case for both sides and it is not sensible to overturn too many apple carts in pursuit of a principle, this being a relativist age, and Hattie not earning, and so early in what he hopes eventually to be a parliamentary career.

Morality, as Hattie recently discovered, is a question of what one can afford. She can afford less than Martyn. Even so, putting the comforter in the baby’s mouth, plugging its distress, Hattie feels guilt. Guilt is to the soul as pain is to the body, a warning that harm is being done. Gender comparisons are odious, as Hattie would be the first to point out, but it is perhaps easier for men to override the emotion than it is for women.

Perhaps I shouldn’t have given Hattie permission to go back to work. Along with the child-care comes guilt, in the form of another pair of hands to soothe Kitty’s brow, another voice to lull her to sleep. Bad enough for Hattie to have bred a baby – and guilt is to motherhood as grapes are to wine – now she must worry about how Agnieszka will react to the baby and the baby to Agnieszka and both to Martyn and back again.

Hattie will have to develop the art of diplomacy fast. Wouldn’t it just be easier to put up with the boredom of motherhood and wait for Kitty to grow up? I feel like phoning Hattie and saying ‘Don’t, don’t!’ but I desist. The girl is not cut out for domesticity. But will Agnieszka influence Kitty’s character, mar her development in some way, teach her how to spit out food and use swear words? I am Kitty’s great-grandmother. I worry. The guilt outruns the generations.

Learned Characteristics (#ulink_28208267-f217-5be2-ac2d-df5591b5022a)

Back in the sixties when we were in our early thirties, living round the corner from each other in Caldicott Square, Serena and I passed au pairs around like hot cakes. Nearly all of them were good girls, just a few were very flawed. But they all made their mark. I am sure some traces of various learned characteristics remain in my children, and in Serena’s too, to this day.

Roseanna, Viera, Krysta, Maria, Svea, Raya, Saturday Sarah – all will have had some input into what they became. Ours may have been the predominant influence, but I’m sure my Jamie learned from Viera how to get his way by sulking and from Sarah how to love in vain. It was from Maria that Lallie the flautist learned to despise us all, but from Roseanne how to value and respect fabrics. Lallie may be falling into bed with a lover but she won’t fling her clothes on the floor. She will place them neatly on the back of a chair, or indeed on a clothes rail. She is prepared to spend hours washing by hand, while I just bung things in the washing machine and hope for the best.

In the days of the many au pairs, I was working in the Primrosetti Gallery for a pittance, Serena was beginning to earn well as an advertising person, and George her new husband had just started his antiques shop. Serena and George lived in a big house in Caldicott Square. The girls lived in the basement, for I had no spare room for them, and though the basement was in its raw early-Victorian state, all damp walls and loose plaster, they did not seem to mind.

I have never been jealous of Serena, she is too amiable and generous for that, and takes her own position in the world lightly, thus obviating envy. She is also, frankly, fat and maintains that this is what has enabled her to survive as well as she has in a competitive world. ‘Oh, Serena!’ people say, ‘Sure she seems to have everything: money of her own making, a nice home, an attentive husband, her name in the papers, creativity, reputation, children – but isn’t she fat!’ And they can’t be bothered even to throw the barbs.