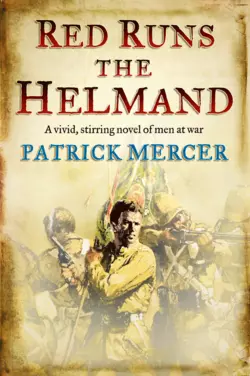

Red Runs the Helmand

Patrick Mercer

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 474.99 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Set in the 1870s, this is a gripping adventure in which Mercer brilliantly reenacts the lives of soldiers in the Second Anglo-Afghan War.Anthony Morgan, now just appointed as general, has two of his sons, one his legitimate heir, one his bastard, both fighting in the ranks.Morgan has arrived just as one of the rival princelings has begun to control Herat, and is determined to carve out some power for himself, and so embarks upon marching to Kandahar, determined to remove the British governor and take the city and province as his own kingdom.Morgan′s life is not made easier by problems with the other generals and in particular his own difficulties in dealing with the growing rivalry between his two sons.