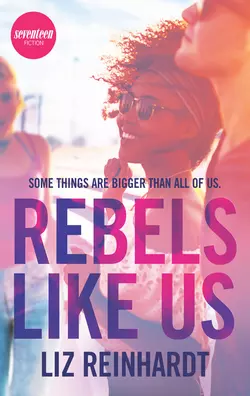

Rebels Like Us

Liz Reinhardt

‘It's not like I never thought about being mixed race. I guess it was just that, in Brooklyn, everyone was competing to be unique or surprising. By comparison, I was boring, seriously. Really boring.’Culture shock knocks city girl Agnes "Nes" Murphy-Pujols off-kilter when she's transplanted mid–senior year from Brooklyn to a small Southern town after her mother's relationship with a coworker self-destructs. On top of the move, Nes is nursing a broken heart and severe homesickness, so her plan is simple: keep her head down, graduate and get out. Too bad that flies out the window on day one, when she opens her smart mouth and pits herself against the school's reigning belle and the principal.Her rebellious streak attracts the attention of local golden boy Doyle Rahn, who teaches Nes the ropes at Ebenezer. As her friendship with Doyle sizzles into something more, Nes discovers the town she's learning to like has an insidious undercurrent of racism. The color of her skin was never something she thought about in Brooklyn, but after a frightening traffic stop on an isolated road, Nes starts to see signs everywhere – including at her own high school where, she learns, they hold proms. Two of them. One black, one white.Nes and Doyle band together with a ragtag team of classmates to plan an alternate prom. But when a lit cross is left burning in Nes's yard, the alterna-prommers realize that bucking tradition comes at a price. Maybe, though, that makes taking a stand more important than anything.

“It’s not like I never thought about being mixed race. I guess it was just that, in Brooklyn, everyone was competing to be unique or surprising. By comparison, I was boring, seriously. Really boring.”

Culture shock knocks city girl Agnes “Nes” Murphy-Pujols off-kilter when she’s transplanted mid–senior year from Brooklyn to a small Southern town after her mother’s relationship with a coworker self-destructs. On top of the move, Nes is nursing a broken heart and severe homesickness, so her plan is simple: keep her head down, graduate and get out. Too bad that flies out the window on day one, when she opens her smart mouth and pits herself against the school’s reigning belle and the principal.

Her rebellious streak attracts the attention of local golden boy Doyle Rahn, who teaches Nes the ropes at Ebenezer. As her friendship with Doyle sizzles into something more, Nes discovers the town she’s learning to like has an insidious undercurrent of racism. The color of her skin was never something she thought about in Brooklyn, but after a frightening traffic stop on an isolated road, Nes starts to see signs everywhere—including at her own high school where, she learns, they hold proms. Two of them. One black, one white.

Nes and Doyle band together with a ragtag team of classmates to plan an alternate prom. But when a lit cross is left burning in Nes’s yard, the alterna-prommers realize that bucking tradition comes at a price. Maybe, though, that makes taking a stand more important than anything.

Rebels Like Us

Liz Reinhardt

LIZ REINHARDT is a perpetually homesick NJ native who migrated to the deep South a decade ago with her funny kid, motorhead husband, and growing pack of mutts. She’s a fanatical book lover with no reading prejudices and a wide range of genre loves, but her heart will always skip a beat for YA. In her spare time she likes to listen to corny jokes her kid reads to her from ice-pop sticks, watch her husband get dirty working on cars, travel whenever she can scrape together a few bucks, and gab on the phone incessantly with her bestie, writer Steph Campbell. She likes chocolate-covered raisins even if they aren’t real candy, the Oxford comma even though it’s nerdy, and airports even when her plane is delayed. Rebels Like Us, her latest YA novel, is full of hot kisses, angst, homesickness, and laughs that are almost as good as the ones that come from the stick of a melty ice pop. You can read her blog at www.elizabethreinhardt.blogspot.com (http://www.elizabethreinhardt.blogspot.com), like her on Facebook or follow her on Twitter, @lizreinhardt (https://twitter.com/lizreinhardt).

To Steph who refused to answer the phone until I swore this book was done, (despite my charms, pleas, and disgusting levels of self-pity) because she knows the purest form of love is also the toughest.

The world is full of awesome best friendships—Napoleon and Pedro, Claudia and Stacey, Jessica and Hope, Frog and Toad—but “Steph and Liz” is and always will be my fave.

I love you to the best doughnut shop in Brooklyn and back, bestie.

WHO’S WHO AT EBENEZER HIGH (#u4b8ddb2a-06a8-5550-9d97-0fa8601bb316)

“Several of your teachers mentioned dress code violations. I sense that there may also be an attitude problem.”

—Ebenezer High’s Principal Armstrong

“Agnes? That cannot be her name. That name would be ugly if it were my grandmother’s.”

—Ansley Strickland, reigning belle and Rose Queen frontrunner

“I like to root for the underdog.”

—Doyle Rahn, senior class heartthrob, Southern gentleman, expert mudder and rebel

“Obviously we have a different sense of humor here than y’all do.”

—Braelynn, Ansley’s BFF and second-in-command, and Rose Court nominee

“What I did? Running for Rose Queen? It’s not breaking any rules. But it’s breaking every tradition.”

—Khabria Scott, cheerleader, nontraditional Rose Queen

candidate and rebel

“Be careful ’round here. There’s some areas that aren’t real nice.”

—Officer Reginald Hickox

“I was never good at walking away from a dare.”

—Agnes “Nes” Murphy-Pujols, high school senior, new girl and reluctant rebel

“I ain’t about to retreat.”

—Alonzo Washington, senior class clown, baseball player and rebel

“Thank you for being the kind of daughter who never stops amazing me.”

—Nes’s mom, NYC transplant, nervous rebel parent

“This old town needs to shake some of the dust off.”

—Ma’am Lovett, Ebenezer High English teacher, supporter of the rebel alliance

“It’s funny because based on the tone of your voice, I would assume you’re not seriously considering melding the two most important things in the world—romantic love and social justice.”

—Ollie Nguyen, Nes’s BFF, bassoon prodigy and NYC rebel

Contents

Cover (#u2033be7a-2e54-50d0-8486-c12721bc6e63)

Back Cover Text (#uf978bb2a-91bd-5783-a1e8-58f79ca25248)

Title Page (#uacdb67d5-aec4-584f-b766-2bb4f8427bae)

About the Author (#u8f016ce2-14ae-51ba-891e-d01638d14808)

Dedication (#u37341f70-2d50-5acf-91a3-72f92d3464e0)

WHO’S WHO AT EBENEZER HIGH (#u29d6597b-d08a-5a91-8f19-fbede61edaa9)

ONE (#u63ff6b0c-3d8b-56f8-ac3d-b1ab2c153ba8)

TWO (#ucb8bb5d5-c3f8-58b5-90f1-932528d90971)

THREE (#ue9ddb79e-c12f-5883-8a2d-005196e9e991)

FOUR (#ub69632c4-b6ab-54a2-a7af-2a586beca372)

FIVE (#u38b36fc2-dcf5-5ca1-8a01-a435e49c9d28)

SIX (#uc9847dbe-e6ac-5151-894f-4959fceb4fb6)

SEVEN (#u890b184f-dca4-58ed-a22c-aed438f1d114)

EIGHT (#u4567801e-df57-553c-a23e-9387f15f3f3e)

NINE (#litres_trial_promo)

TEN (#litres_trial_promo)

ELEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

TWELVE (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

FOURTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

FIFTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

SIXTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

SEVENTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

EIGHTEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

NINETEEN (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-ONE (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-TWO (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-THREE (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-FOUR (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-FIVE (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-SIX (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-SEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-EIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-NINE (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTY (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTY-ONE (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTY-TWO (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTY-THREE (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTY-FOUR (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTY-FIVE (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTY-SIX (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTY-SEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

THIRTY-EIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

ONE (#u4b8ddb2a-06a8-5550-9d97-0fa8601bb316)

Sartre said hell is other people, but he obviously never experienced a winter heat wave in the Georgia Lowcountry. Six weeks ago, my best friend and I were drinking cocoa laced with swiped rum, huddled under covers on the couch, oohing over the fat, lacy snowflakes that drifted into frozen piles on the sidewalks. Today, I’m trying to resist fainting from the broiler-like temperatures. In winter.

No wonder there are twelve churches within a five-mile radius of my new house. If this is the kind of fiery heat Georgians deal with on a regular basis, the idea of hellfire must be a terrifyingly real threat.

The sun follows me like the creepy eyes in a fun-house portrait as my sneakers sink into the melting blacktop. I hesitate and stare at my distorted reflection in the glass of the school’s double doors. I’m still attempting to decode the movers’ unintelligible boxing system—yesterday when I opened a box marked Art I found my collection of Daler-Rowney watercolor paints tossed in with an eggbeater and a dozen of my mom’s old yoga DVDs—so my antifrizz balm is still MIA. With it, my hair falls into lopsided curls. Without it, I have to deal with my current situation—a dark cloud of frizz with a life of its own. It probably didn’t help my hair’s general health that I guilted Mom into letting me get the underside stripped, bleached, and dyed bright pink before we left the city. I need a hair tie. Or to get out of the pummeling sunshine before it fries my hair beyond recognition. I seriously love my curls, but I do not love what this crazy humidity is doing to them. Before I left the house this morning I decided that, despite my life going off the rails, I looked smoking hot. Now I look like I just made a quick run to the store and back for one of my aunties on a scorching August afternoon in Santo Domingo, even though all I did was walk across the school parking lot in Georgia. In the middle of winter. The only deliverance from this heat is inside the squat monstrosity that is my new school, Ebenezer High, so I need to make a decision: go inside or die of heatstroke.

“Coño,” I mutter, and it’s like I can feel my father frowning an ocean away. Why is it the only Spanish you ever speak is slang and curses, Aggie?

I shake his words out of my head and take a long look at the place I’m going to call my academic home for the second half of this, my all-important senior year, and I have to wonder if the builders accidentally opened the schematics for a psych ward or a minimum-security prison and didn’t realize their mistake until appalled administrators and teachers showed up postconstruction.

I fill my lungs with a final gulp of suffocatingly hot air, then push into the cool building, cross a lobby showcasing dozens of glittering gold sport trophies, and I’m in a generic front office where a woman with a big smile and bigger hair inputs my information into the computer at a snail’s pace. I heard things are more relaxed south of the Mason-Dixon, but if they’re this relaxed, I may never make it out of the front office.

When my official schedule is finally approved, I’m introduced to the guidance counselor, who leads me into a hallway that smells like yesterday’s cafeteria fries, bleach, and fresh paint. I crane my neck to better take in my new school and wonder if the dingy gray-blue color they’ve chosen for the walls is also a leftover from some institutional torture chamber. I’m used to seeing art displayed on every wall and bright splashes of random colors painted in crevices too small for anything else. This sterility is strangely claustrophobic.

While I’m trying to breathe without the help of a paper bag, I wonder again why I’m even here. My brother, Jasper, told me point-blank that he thought I’d lost my mind the day I announced I was migrating South for the spring term, like some freak-of-nature bird. My father insisted we phone conference half a dozen times so that he could lecture me in Spanish on the merits of a New York City or Parisian education over an education from Georgia—which he insisted was an oxymoron. My abuela says my dad has been manso—very chill—since the day he was born, but talking about my future is the one thing that can make him quillao—super upset. Ollie, my sister from another mister, would have shared her tiny bedroom with me in a heartbeat if I’d asked, but I’d never stoop to asking. I’m well aware my passionate, motivated bestie needs every available inch of room so she can focus on her intense practice schedule and the whirlwind of spring recitals. And Mama Patria, my abuela, has room at her apartment but she lives two subway lines and a half hour bus ride away from Newington—that just wasn’t a commute I could’ve tackled twice a day, every school day, especially during the longest, coldest winter to hammer New York City in fifty years.

As far as Paris goes, I’d never admit it to my father, but my French skills have slipped—a lot—since he and Jasper moved and there was no one to ignore me until I asked for the salt or the remote or the time en français. To say my language skills have rusted would be an understatement—my French is basically a series of crumbling linguistic holes.

On top of all that there was the lingering poison-gas fog from my breakup with Lincoln—my first love and one of my best friends turned mortal enemy—which would have suffocated me slowly if I’d stayed at the private school he and I both attended. Lincoln and I started dating when we were sophomores, the year his parents started an exchange program for Maori soccer players with Newington High, and there are reminders of our coupledom sprinkled around every corner in the school where he was basically treated like royalty. I reveled in the fact that I couldn’t pass the main hall without seeing our entwined initials on the art tile we’d painted, or his gorgeous face—broad jaw, wide nose, sparkling eyes, dark skin, plush kissable lips—on the Newington VIP board in the main hall. Lincoln pulled me close and kissed me for the first time in the courtyard under Newington’s legendary oak while gold and orange leaves swirled around us. I’d never once passed that tree without running my fingers over the bark and smiling—well, I never had before.

The last months of senior year are so useless and so meaningful all at once. Everyone solidifies college choices, skips any day they possibly can, and gets disgustingly nostalgic about the people they’re going to leave behind on graduation day. The last thing I wanted was to spend months dodging the yearbook photo montages and avoiding fondly retold memories that would only reinforce what a total lie my entire relationship with Lincoln turned out to be in the end.

I have to look at my decision to flee less as losing out on the last months with my friends and more as moving on a little bit early. I’ve always had an independent streak, so I might as well run with it. It’s best if I consider my time in Georgia a kind of study-abroad semester before the adventure of college begins.

My tour guide’s bubblegum drawl interrupts the panic that threatens to tunnel me under despite my internal pep talk that this will all be okay.

“It’s wonderful to have you at Ebenezer High. We realize it will take a few days for you to get settled, but we’ll let you jump right in. The good thing is you’ve only missed one day of second semester, so you should be able to catch up easily. First day of a new semester is mostly just the syllabus breakdown anyway.” She gestures to a wooden door, and I peek through the tiny window into what looks like a lab full of students dying from a combination of boredom and heatstroke. “This here will be your first class tomorrow, Agnes. Mr. Hemley, AP physics. At this hour you’d be in the middle of your second class, which is...”

Newington was once some founding senator’s house and had windows so huge, it never even felt like I was indoors. The windows in this school remind me of the slits in medieval fortresses that archers shot arrows out of. What the hell is the modern purpose of windows that narrow? As I pass the classrooms, I see sad ribbons of sunlight, bitterly determined to brighten the gloom.

Give up, sunshine. It’s a damn lost cause.

“...this one right here.” We stop in front of another nondescript door whose tiny window reveals my fellow cell mates. “The peer guide I’ve assigned to help you through the day is in this class. She’ll give you a more thorough tour, and if there are any questions she can’t handle, feel free to stop by my office anytime. The door is always open.” Her silver fillings wink at me from the back of her mouth when she smiles. I can’t remember her name no matter how hard I shake my brain.

“Thanks, but I’m pretty sure I’ll be able to navigate all right on my own.” I turn the schedule she handed me so that the map printed on the bottom is oriented, and bend my lips up in what I hope approximates a smile.

“Whatever you’d like, Agnes.” She shifts from one sensible pump to the other.

“Okay. Thanks again. I’m, uh, going to class now.” I point to the doorway I don’t particularly want to walk through.

What’s more awkward? Walking into a classroom full of seniors as the new girl? Or standing in the ugly hallway of your new school losing a staring contest with a guidance counselor whose name you can’t remember?

Lamest game of Would You Rather. Ever.

Coño, I have to choose, so I walk backward through the classroom door, keeping that demented smile wide until Mrs. What’s-Her-Face disappears into the shadows of the hallway.

“Good morning. You must be Agnes.” A woman with a no-nonsense voice gives me the evil teacher eye over tortoiseshell glasses that perch on the end of her broad nose. Even with her springy, salt-and-pepper curls factored into her height, she only grazes my chin. But the fact that I tower over her doesn’t stop me from squirming under her laser gaze. She has the same huggable, curvy figure and beautiful, soft, dark brown skin as my grandmother, but I cannot picture her taking a tray of warm coconetes out of the oven. I can picture her silencing a class of hooligans with one fiery look. “I’m Mrs. Lovett.”

“Good morning.” I modify my smile from demented pretend to real. I hate unnecessary authority, but I absolutely love ball-busting, no-nonsense bitches. I get the latter vibe from Lovett already.

“Ms. Ronston wanted me to let you know your peer guide will be Khabria Scott. Khabria, please raise your hand.” Mrs. Lovett’s voice snaps, and a hand pops up in response. I approve of my tour guide’s bold nails—matte black except for a shiny white ring finger nail, gold fleur-de-lis designs glittering on each one.

Because I’m nervous, I resort to a goofy, toothy smile, and feel extra dumb when Khabria folds her arms across her chest elegantly and gives me a tight-lipped, polite smile in return. She’s got this whole regal Nefertiti/Beyoncé vibe that’s intimidating and impressive all at once.

“You can take a seat second row, fourth desk back, Agnes.” Mrs. Lovett makes a mark in her roll book, and I slide into my chair while too many eyes dart my way, sizing me up because I’m so shiny and new. It’s uncomfortable but not mean.

“Hey. Hey, new girl?” A tall, good-looking guy with a bright yellow basketball jersey sitting just behind Khabria nearly falls out of his chair calling to me and waving his gorgeously muscled arms over his head. “Where you from?”

“Crown Heights.” I watch his face screw up like I answered him in Finnish. “Brooklyn.”

“Where?” He kicks the back of the Khabria’s chair as he tries to settle into a desk that clearly wasn’t designed for people over six foot six. Khabria whips her head so fast her black and strawberry braids are a blur.

She mutters, “Holy hell, you a moron, Lonzo.”

“New York City, man. C’mon, you’re makin’ us all look ignorant.” I can’t see who said it, but that deep, slow voice that rolls like a warm wave in the ocean is the most Southern voice I’ve ever heard—and I’m shocked by the fizzy glow that warms through me at the sound of it. I like it. I like it a lot.

“Why’d you move here?” The tall guy kicks my chair with the sole of his shoe to get my attention. When I turn to look at him, he grins wide, the way I smiled at Khabria before. “Too violent in your hood?”

“What?” I snort as thoughts of the last co-op meeting flit through my head. Old Mr. Madsen almost got in a fistfight with the “young hipster” who dared to adorn the communal herb garden with his found-art whirligigs, which Mr. Madsen screamed were “pretentious trash.” The meeting ended with Mr. Madsen knocking all the disposable coffee cups off the snack table and vowing to recycle the young hipster’s “eyesores” if they came anywhere near his flat-leaf parsley. “I lived in a really nice neighborhood. Not a hood.”

I mean, sure, there were the Crown Heights Riots, but that was way back in the ’90s. Ancient history.

“So why then?” Despite the twitchiness of his limbs, his dark eyes are calm.

When he repeats his question, more eyes turn to me from around the classroom. Shiny-haired cheerleaders and flexing jocks, slackers trying to pretend they aren’t dozing, nerds clutching their notebooks—two dozen faces fade in a kaleidoscope of dark and light as my vision tunnels.

Being the new girl sucks.

“Uh...”

“You hate snow?” He rubs a hand over his tight, dark curls and clicks his tongue when Khabria stomps her sneaker in frustration.

“No, you need to stop, boy. Who would hate snow?” She throws her arms out and rolls her eyes like it’s the most ridiculous concept she’s ever contemplated.

“You ever even seen snow?” He juts out his chin.

“No, but I want to. You trying to say you don’t want to ride on a sled? Or throw a snowball?”

“I heard snowballs hurt your hand.” He holds out his own hands, so big they could probably palm a basketball with zero problems. He flips them, studying his knuckles and then his palms like he’s trying to get a gauge of the damage a snowball could do.

I’m shocked silent. No snow? Ever? It’s a lot to wrap my frostbitten brain around. Despite the intense heat here, I feel like I still haven’t thawed completely from the last cold snap back home.

“Alonzo Washington, please stop harassing Agnes and come discuss the status of your term paper proposal with me immediately.”

The guy—Alonzo—leaps out of his seat and says, “Yes, ma’am,” like he’s a soldier in a very obedient army.

I’m about to go back to imagining a life devoid of snow when I hear a little alien-baby voice whisper, “Agnes? That cannot be her name. That name would be ugly if it were my grandmother’s.”

I swivel my head and face the kind of blandly vicious sneers that always seem to infect a select few in any group. My cousins in Santo Domingo would say they’re bocas de suape—mop mouths. In translation, they’re two losers who don’t know when to keep their traps shut. They’re so generically pathetic, if life was a movie, they wouldn’t even have names in the credits. They’re even wearing cheerleading uniforms. Could they be more cliché? Generic Mean Girl One is giggling like mad along with Generic Mean Girl Two. I turn full around in my seat and stare at them, ignoring my new teacher’s obvious throat clearing.

“Is there a problem, ladies?” she demands.

“My name,” I announce, still looking at the two overzealously spray-tanned, hair-tossing idiots in their cutesy matching uniforms. I love the way their cackles dry up and their perfectly made-up faces fall. “Apparently it’s hilarious.”

“Agnes.” I turn to look at my teacher, whose pursed lips and cocked eyebrows tell me she is clearly not amused. “Whatever this nonsense is about, it stops now. I don’t tolerate fools, and I don’t put up with time wasting. In fact, it’s really starting to piss me off that I wasted this much time already.”

A few people gasp or snort when she says piss, as if our innocent, nearly adult ears have never heard a single naughty word before.

“I’m sorry for wasting your time,” I say, sitting straight at my desk. I can take care of the Generic Mean Girl Twins later. Right now, I’m going to make it a priority not to “piss off” this woman. For all I know, this class might be the highlight of an otherwise miserable few months.

“Ma’am.” She crosses her arms over her wide chest. The idiotic giggles start again. I’m drowning fast.

“Me?” I point at myself. Mrs. Lovett’s nostrils flare very slightly.

“Me.” She points a thumb at her chest. “When you speak to me, your instructor, you refer to me as ma’am. Clear?”

“So, not ‘Mrs. Lovett’?” I swear to baby Jesus, I ask only to double-check, but I guess I’ve already walked too close to the edge of the smart-ass line, and now my classmates are hooting like I’m the Pied Piper of classroom anarchy.

“Do not test my patience today, Agnes,” Mrs. Lovett snaps. She slaps a paper packet and a copy of The Old Man and the Sea on my desk.

I leaf through the tattered pages, hold it up, and attempt one last smile that’s basically just me grasping at straws. “No friend as loyal.”

Mrs. Lovett’s lips twitch, and I curl my fingers around the old misogynistic tale of oceanic triumph and New Testament allusions, waiting to see if her lips will twitch up or...

Up. Smile. Score!

But now that I bought her love back with a cheap quote trick, I have to be on my best behavior while we scribble notes about Hemingway’s boozing and hunting and womanizing—and that means keeping my mouth firmly shut. Because, despite my best intentions, whenever I open my mouth, trouble finds me.

Also, I’m still not sure about the whole ma’am thing.

When we’re finally dismissed, Alonzo drags Khabria over to me.

“Agnes, tell this know-it-all that it hurts your hand to make a snowball.”

“Um, if you don’t wear gloves, it stings,” I admit reluctantly. I’m breaking a deep, unwritten girl code by siding with Alonzo, even on a matter this insignificant, but...

“See! I told you! Ooh, you so wrong!” Alonzo crows, shimmying his arms at his sides and strutting around Khabria in a weird, end zone type celebration dance. “My daddy told me when he was in Lamaze class with my mama they made everybody squeeze an ice cube to let them get a taste of labor pain.”

“Um, it’s uncomfortable, but I don’t think it’s anything like labor,” I cut in, but Alonzo is flapping his elbows like a chicken while Khabria sucks her teeth and sputters. I fear for Alonzo’s life if he keeps poking this very beautiful, probably lethal bear. “I mean, it’s mostly fun, not painful...” I trail off, and Khabria shakes her head.

“Ignore that fool. He actually enjoys being a dumb ass.”

It occurs to me that I could stick out my hand and introduce myself—no! Maybe that’s too weird?—but before I determine if the chance to make a new friend outweighs the incredible social awkwardness, Alonzo’s sauntered up to his group of cronies and Khabria is gliding away to join a clutch of girls wearing navy cheerleading uniforms that match hers—including both plastic airheads from earlier. Ugh, maybe I should be glad social awkwardness won out before I tried to befriend someone who hangs out with the twit twins.

I try to convince myself I dodged a social bullet, but it doesn’t feel awesome to be left hugging my books and wishing I could teleport to my next class so that I won’t have to suffer being the one and only student at Ebenezer High navigating the halls alone.

And then, suddenly, I’m not.

“Hey! Hey, Agnes!” Khabria’s tiny cheerleading skirt swishes around her long legs as she jogs down the hall after me. “I’m your peer guide today.” She tucks a loose red braid back into her updo and gives me a slightly bigger smile than when we first met.

It’s probably just a coincidence that the clutch of cheerleader clones she left down the hall erupts into squawks of laughter at that exact second.

Probably.

Panic feels like quicksand sucking at my ankles and threatening to pull me under. I half choke out my next words.

“Uh, no worries. I have this handy map.” I flutter the wrinkled paper between us like I’m waving a white flag. I surrender to social isolation—leave me alone in my misery. “I’ve been riding the subway alone since I was a little kid. I’m sure I can manage the halls of a high school.”

Khabria nabs my schedule and cocks an eyebrow. “Really? Because your next class is back that-a-way.” She jerks a thumb over her shoulder as I grab the map back and try to get my bearings. I usually have a decent internal compass. I guess I’m just off-kilter today.

“Right. That way. Okay. I got turned around, I guess.”

Senior year. I’m supposed to be directing freshman to the nonexistent fourth-floor pool, not getting lost going down the main hall.

“I know it’s not the subway, but finding your way around here can be tricky. Let me give you a quick tour at least.” Khabria’s dark eyes warm with the kind of sympathy I’m used to giving, not receiving. I definitely prefer being in charge, not being led around. But I guess I don’t have much choice now.

“Okay. So...I see my next class from here. After that I have to head across this courtyard...or, wait? Is that a stairwell...?”

“C’mon.” Khabria marches me to my next classroom and bats her lashes at the cute young teacher manning the door. “Mr. Webster, this is Agnes. It’s her first day, and I’m her peer guide. Is it okay if I take her on a quick tour once the halls empty?”

Mr. Webster crosses his arms over his wide chest and sighs. “Ten minutes, Ms. Scott. Agnes will already be playing catch-up.”

“Fifteen? Please, sir?” she says, bartering with a flirty edge to her voice and biting her bottom lip for good measure.

Mr. Webster looks decidedly uncomfortable. He takes off his nerdy-cute glasses and cleans the lenses with the tail of his half-tucked dress shirt. “Fine. Go, quickly, so you can get Agnes back as soon as possible.”

“Thank you, Mr. Webster,” she singsongs. We leave him frowning at his polished shoes.

Khabria whirls me down the hall, giggling the whole way, and I feel normal for a split second. When we’re at the stairwell, she tugs me close, glances over her shoulder, and dishes some seriously crazy gossip. “Webster tries to play it cool, but everyone knows he’s dating a girl who just graduated last year...and they started seeing each other before school was out.” Her eyes go wide and her perfect eyebrows rise up until they almost disappear in her hair.

“Did they get caught?”

There was a rumor about one of the teacher’s aides and a senior at Newington when I was in tenth grade. But the rumor barely had time to circulate before the aide was gone without a word. I can’t imagine what it would have been like if we found out the rumor was true, then passed that aide in the halls every day...

“No, but we all know it’s true. He was at a few high school parties over the summer, always looking like he wanted to disappear. Oh, here are the math labs, and your next classroom after you leave Webster’s class is the middle one.” She waves a hand at a cluster of rooms filled with students silently scribbling complicated geometry equations on whiteboards, then sneers. “I don’t know why he’d risk showing his face where there could be students around. I mean, it’s not like anyone told on him, but someone could’ve, and now he can’t get respect no matter how tough he tries to act because how do you respect someone with that little sense? Last year, he was one of the strictest teachers we had. This year, I think he’s just waiting on us to graduate, so one more class that went to school with his little girlfriend will be gone and out of his hair.”

Khabria’s words cut like a razor through tissue paper, and I realize she’s almost gleeful. I kind of get it. Right or wrong, there’s a certain thrill in holding power over the people who are supposed to be in authority, especially when they screw up.

“Has he ever made a pass at any of the other girls?” I ask. I try my best to avoid gossip for the most part, but there’s something weirdly comforting about it. It gives you the illusion you’re sharing a secret—even if the secret is something everyone in school is talking about.

“Nah. Apparently it was true love with him and that one girl, or whatever. Guidance office.” She points and it’s reassuring to see the familiar “mountain climber with an inspirational quote underneath” poster that must be required decor for every guidance office in the country.

“That’s crazy,” I murmur as I poke my head in and peek at the out-of-date computers and dusty college manuals. “I’d probably quit if I were him.”

“People ’round here are stubborn like that though.” She shakes her braids out with her fingers. “My gram always says people have more pride than sense. They’d rather be miserable than admit defeat. I think some people just like being miserable, period.” We stroll down a back hall. “Food science, shop, child care, music room,” she ticks off.

“I definitely get that vibe from some people.” I decide to test the waters. “No offense if they’re your friends, but those two cheerleaders in our English class seemed pretty bent on spreading misery...at least toward me.”

Khabria’s pace slows and a blush warms the deep brown skin over her perfect cheekbones. “People sometimes forget we’re supposed to be hospitable to newcomers, especially if we’re on cheer. I know the other girls came off badly today, but their bark is definitely worse than their bite. They prolly thought they were being funny or something.” She shrugs. “That whole pride thing. Don’t take anything they say to heart. Maybe it’s a side effect of being squad leaders every year since we were in peewee cheer—maybe they’re just used to ribbing on the new girl.”

“So they’ve always been the queen-bee types?” I can so imagine the Generic Mean Girls as preschoolers with pigtails and bows, lording over the snack table while they nibbled their graham crackers and sipped their juice boxes.

“Ain’t my queens,” Khabria bites out. She sighs and takes it down a notch. “Look, some people are really into cliques here. They have their friends, their jokes, their way of doing things... If you don’t like them, my best advice for you is just stay away.”

I realize I touched a nerve, and I get it. There are girls I would have counted as my best friends in middle school but haven’t spoken a word to in years—girls I’d still defend if anyone else tried to talk crap about them. People—even people you care about—can change so fast, and loyalties get complicated.

“Sorry. I didn’t mean to imply anything.” By now we’ve rounded back to the main hall and Mr. Webster’s class, all the initial closeness we shared over steamy gossip withered.

“Agnes, Khabria!” Mr. Webster pokes his head out the door, calls down the hall to us, and taps his watch in warning. “You’re five minutes late. Let’s hustle.”

“Thank you for showing me around.” I clutch my map in shaking fingers, off-kilter after possibly offending the first person who was actually nice to me.

“You’re welcome. Let me know if you need help with anything else today.” Khabria’s voice runs as cold as the water around an iceberg. She hesitates, then says, “Look, most people here are good folk. We get along, we help each other out. Don’t judge anyone too harshly based on a few minutes of knowing them.”

I watch her skirt flutter as she flounces away before I can answer, and I slip into class. My classmates text on their phones, paint their nails, and chat as Mr. Webster robotically lectures, his body language limp with defeat. I wonder if he regrets anything. I wonder if staying here at Ebenezer was him standing his ground or giving up.

If I stay here, would it be standing my ground or giving up? Bells ring, classes move, and I follow my map like a pro now that Khabria’s shown me the basic layout. For the rest of the day, I’m mostly ignored. Which is fine. I’m only enduring. Just a few months.

Just the rest of my senior ye—

It’s like I accidentally pulled the plug on a hot bubble bath. I search under the suds to plug it back up because if I don’t, every single emotion I’ve kept bottled up will drain, hot and wet and embarrassing.

No girl who grew up on the mean streets of Brooklyn (all right...fairly gentrified Crown Heights, but still) is going to cry on her first day of school in Nowhere, Georgia. I’d have to beat in my own ass. It wouldn’t be pretty.

The final bell tolls and crowds press out of doorways and into the hall on every side of me, a tsunami of bodies. I don’t care about being jostled, but it’s weird to not have a solitary soul waiting for me by a locker or gesturing for me to sneak down a back hall and beat the rush.

I sprint alone to my little Corolla—a poor consolation prize from my mother to make up for the dissolution of my pretty rad life because of her screwup—and peel out. I choke on the diesel fumes from the line of lifted pickup trucks that leads home.

Home.

That’s the word on repeat in my head when I veer the car to the side of the road and pull the damn plug, unstop everything I’ve been holding in. I’ve felt seconds away from drowning all day, and now I weep and scream like a banshee on meth in the semiprivacy of my car, letting it all drain out.

“Vete pal carajo, Georgia! Concho hijo de la gran Yegua!”

I curse this godforsaken state at the top of my lungs and beat the steering wheel. I drum my heels on the floorboards. I scream curses over and over until my voice is hoarse. And then I wipe the mascara out of my eyes, blow my nose, take one deep breath, pull back onto the road. “Coño.” Damn. There’s nothing left to say, so I glare at the obstinate sun, and go...home.

God, it would feel good to spill my guts to Mom the way we used to, Lorelai and Rory–style, but the time for sitcom mother-daughter banter is long gone. When I look back at all the times I assumed she was doing something awesome, like tutoring one of her struggling students, and realize she was, in fact, doing something skeevy, like flirting with a married dude, a bone-crushing feeling of betrayal presses onto me. It’s as if I was waiting at Luke’s with my giant mug of coffee, but my mother never showed.

I wonder if I’ll ever be able to look at her and forgive her for selfishly and systematically ruining my life. Ruining our life. All because of a skinny, kinky weirdo with a weasel face and my mom’s very, very poor tech skills.

Word to the wise, kids: don’t be a fat-fingered idiot when you’re sexting with your married coworker. Because you just might accidentally send a pic of your naked ass to the HR secretary instead of your paramour. And said secretary just might be your weasel-faced sex partner’s wife’s yoga buddy. And then you and your innocent daughter will be unceremoniously exiled to the sweltering marshes of Nowhere, Georgia.

TWO (#u4b8ddb2a-06a8-5550-9d97-0fa8601bb316)

In the quiet sanctuary of my temporary home, all I want to do is forget the total disaster that was the first day of what’s probably the biggest mistake of my life so far. Mom’s teaching a class and won’t be home for another two hours, so I have unsupervised time to kill.

There are very few perks that come with living in Georgia, but a big, refreshing one is the pool in the backyard. I can practically hear the pool pump hissing, “Come swim in me, Nes.”

I tear to my room and rip open a box labeled Summer Clothes, then a box labeled Vacation, then, in a desperate last-ditch effort, I peel back the tape on one labeled Random Fun Stuff. I find a pair of denim overalls I don’t remember buying, some really old family pictures from the summer we went on vacation to some hokey middle-America theme park, and three yo-yos from my brother’s obsessive yo-yo-collecting days back when he was a nerdy middle schooler (instead of a nerdy college sophomore). I get nervous because I’m not sure where else to look for my lone piece of missing swimwear. I own exactly one bikini.

There’s not an especially long swim season in New York, so one will do. But it’s January here. January. The time of post-Christmas blizzards and sticking to resolutions you made for New Year’s, if you’re all about that. And it’s now hotter than it was when we arrived this hellish December.

I may need more bikinis. In the dead of winter. Unbelievable.

Our Realtor said this was an “unusually hot one” as she fanned her sweaty face and bemoaned every house we looked in that hadn’t switched on the central air. I expect bikini shopping and sweltering heat in Santo Domingo over summer break; this is just madness.

I continue to frantically pick through the cardboard box ziggurat in my room and finally snag the stretchy material of my lone bathing suit in a box labeled Underwear. Fair enough. And I can’t even blame the movers’ crazy box identification because I packed that one myself. Just as I’m about to change, my phone rings and I realize I may have to pick up and talk intelligibly to another human being when all I want to do is dead man’s float around the pool and feel sad for myself. The groan I bite back is a knife of guilt that twists in my gut.

Ollie wants to FaceTime.

My bleary, makeup-smeared image reflects back at me on the screen, and I want to sob. Again. But then I’ll look even worse. It’s all pretty chicken-and-egg.

“Olls, I look like a gargoyle!” I screech the second she connects.

Her gorgeous face, moon round and ethereally peaches and cream, takes up the entire screen, and my throat feels all clawed down both sides because I’m not sitting in her parents’ modern, artsy apartment, gorging on the Vietnamese sizzling pancakes Ollie is a genius at whipping up and sneaking sips of rice wine from her parents’ enormous collection before we get down to our homework and daily two-person merengue party.

“Shuddup! You look like a goddess.” She gnaws on her lip. “Hey, I checked your Insta this morning...”

“Right.” I shrug. “Call me melodramatic, but it was surprisingly hard to scroll through all those pictures of everything and everyone I was leaving behind.” I take a second to steady my voice, the same way I steady my raw heart every time I flip through my winter photo folder—which is full of pictures of people and places that are a thousand miles away. “I promise I’ll get a new one going soon.”

I guess Ollie hasn’t checked Snapchat yet, or she’d be calling me out about that too. I deleted my account late last night after getting shocked by another surprise Lincoln cameo in a mutual friend’s post-winter-break video. If pictures are hard for me to look at, there’s no way I can handle seeing and hearing video footage of everything I’m missing back home... Plus Lincoln would be like a ghost haunting every Newington clip.

“You really should. Your Insta pics were goals. Plus I want to know what things look like down there. Are there all those mossy trees like in Scooby-Doo? And plantations everywhere? Are they haunted? Did your mom buy you the Mystery Machine to drive around in? Are you wearing ascots and miniskirts? Did you get a Great Dane?” Before she can yell zoinks, Ollie’s eyes dart over my shoulder and go wide with worry. “Wait. You still haven’t unpacked?”

“It’s ‘asylum chic.’ Like it?” She shakes her head and sighs, so I confess. “Truth? It’s a reminder that I won’t actually have to live here forever.”

I wave a hand at the mattress on the floor, covers and pillows piled on it. That, my docking station, and a few choice boxes with the flaps permanently open make up my entire bedroom decor. The movers put all my boxes in my room for me, but I declined when they offered to put my bed frame together. That felt too permanent. Mom made several passive-aggressive comments about how she wouldn’t have bothered to pay an arm and a leg to move all my furniture if I wasn’t even going to set it up, but I stared at the ceiling until she left me to my misery. She was excited to finally have a space bigger than a couple hundred square feet to decorate, and she didn’t get why I wasn’t revved up to be in a new room that’s almost triple the square footage of my old room.

Because I miss my tiny, cramped, perfect old room.

“I miss your old room,” Ollie admits, echoing my internal thoughts with her freakish bestie ESP. Her shoulders slump, and my heart follows their lead.

“It’s okay.” No one brings out my reluctant optimist like Ollie. I hate seeing her down, so I put on a good game face no matter how crappy I feel. “Mom and Dad had been planning to sell our place when I moved to college anyway, and it went for way over asking price, like, the first week it was on the market. They were pretty psyched about it, and I...I’m trying to accept my fate at this point. You know I’m a ‘rip off the Band-Aid’ type when it comes to dealing with emotional stuff.”

“Um, yeah you are!” she laughs. Then gets dead serious. Lecture-time serious. “Speaking of college...”

“I got all my applications in by the deadlines, I swear to God.” I don’t tell my best friend that I hit Send on my SUNY application literally two minutes before midnight on the last possible day. And I don’t elaborate on the fact that I never took my brother up on his offer to proofread my personal essay. I didn’t have the patience to be ridiculed on my native-tongue grammatical failures by my own trilingual flesh and blood.

“You’ll tell me when you hear back?”

“Of course.” I cross my heart with the hand that’s still clutching my bikini, and Ollie freaks out.

“Are you going swimming?” The screen goes down for a second and her shocked voice floats through the speaker. “WeatherBug says it’s eighty-five in Savannah. How is that possible?”

Her face pops back on the screen, and I roll my eyes. “Because Savannah is actually an outer ring of hell. Don’t be jealous. I spent all day with sweaty pit stains. It’s gross.”

“It’s actually not frigid here. Like we could have watched those hot Puerto Rican guys play basketball from your fire escape if we’d had a blanket. Or three.”

“Are you trying to drive me to suicide?” My voice wobbles like the ankles of a first-time ice-skater.

“Sweetie.” Ollie says it on the longest sigh. I know exactly what direction her lecture is going to take, because she’s given it to me a few dozen times before. “Why didn’t you stay here in the city? With me? My parents love you. Or with your abuela. Even if she would have welded one of those chastity belts on you...it maybe would have been better than getting trapped in Georgia. Right?”

“It’s not chastity-belt bad here.”

“No...?”

I think about how I can go to an Episcopal, Baptist, Lutheran, Presbyterian, Nazarene, or Seventh Day Adventist church if I walk five blocks from my house, but an Americano is an unknown species around here. I haven’t found a single decent coffee shop.

“You have a point...”

“You could come back.” She makes her voice small, like she’s trying to disguise the hope so that I won’t even notice it. Fat chance.

Not only do I notice it, big and comfy and bright as it is—it makes me ache.

“I know.” I do. I made a huge, complicated pro-and-con list on butcher paper in my room and stayed up for a full twenty-four hours contemplating it the night before I made my final decision. “But she’s still...”

“Your mom.” Ollie nods.

“Yup.” The word swings like a wrecking ball.

She chews on her lip and gives me space to be angry. I’ve needed the geographical equivalent of Russia and most of China in terms of anger space. But all that roaming anger is getting narcissistic.

“And he’s still...” She lets the words hang.

“Olls,” I beg, but she’s relentless in her quest to make me face my emotions.

“He was your first love, Nes. And he broke your heart. He’s a dog, but you can’t beat yourself up because you miss him. You need to let yourself feel everything. Don’t clam up.”

The tears coat my eyes like a hot, glistening windshield. When they plop out and make their pathetic slide down my cheeks, I know Ollie won’t say, “Don’t cry.” I tend to squeeze my emotions into a bitty ball I can ignore. Ollie is a “cry it out” advocate.

“I do miss him.” It’s hard to be honest when honesty makes me feel so weak and stupid.

“That’s okay.” The sound of her voice is a balm to my frayed emotions.

“I mean, he was my best friend other than you. I can’t think about him without remembering how good the good times were—it’s bizarre how it changed so slowly. How did he go from being the guy who could always make me laugh to the guy who pulverized my heart?”

“I know,” she says.

“I was scared, really scared to leave home and Newington and you,” I say as I lick a few salty tears off my cracked lips. “But I was more scared of staying and facing him every day, because what he did to me is unacceptable—but sometimes I forget because I’m busy remembering how sweet he can be. How can he be such a snake in the grass and legitimately one of the most interesting, caring people I’ve ever met? He messed up so badly, but I know he still cares about me. That’s dangerous.” I take a deep breath and look at Ollie’s face, just a screen away. “I was scared of falling for him again after everything he put me through. Because a little part of me is always going to love the goofy, smart, sweet guy I fell in love with two years ago.”

“Oh, Nes.” I know Ollie would hug me if we were together, and I want to cash in on that hug more than I’ve ever wanted anything.

“I’m a coward.” I close my eyes.

“Stop it. Right now. You’re the bravest person I know. I love you.”

“I love you, Olls. And I’m going to be okay, promise. I’m letting all the gross feelings come out, just in little drips and drabs. Did I produce enough tears for you today? Can I go back to pretending I’m hard-hearted and cool?” I joke. Or half joke.

I know Ollie still wants a full rundown of my first day of school, but I don’t have any energy to tell her about all the crazy crap that kind of threw me for a loop today. It’s childish, but I want to pretend I started the second semester of our senior year at Newington Academy with her. We met in the friendly halls of our Quaker school when we were in second grade and she yelled that she loved my glittery stockings and I yelled that I loved her heart necklace and our teachers shushed us as we tried to yell more compliments back and forth. We found each other at recess, and we’ve been madly, completely best friends in love since then.

“I miss you like butter misses popcorn,” she mourns, and the sight of her tears firms up my backbone.

“Stop crying! Did Parson give you permission to run your bead-and-bracelet biz in the front hall?” I change the subject fast, and it works. Sort of.

“Yes! The middle school girls were all primped out in their Christmas/Hanukkah duds... Nes, they’re crimping their hair! Why didn’t I ask Santa for a crimper too? I both want to scorn them and buy a crimper with all the fat moneys I’m making weaving little unicorn beads into their hair. Advice?” She wipes the tears away with the tip of her fingers.

“No scorn. They’re littles. Remember how much the scorn of the cool upper-class girls hurt our souls back when we were tiny? Also, no crimper. If you want your hair to look like Bride of Frankenstein’s, just braid it when it’s damp.” I tap my finger on the screen, over her face. She opens her mouth like she’s going to bite it.

Our laughs are sadder than I want them to be.

“And, I almost forgot to tell you... No, I’m going to make you guess. Guess how else my life is turning to crap,” Ollie orders.

Her words stab more than a little. I know I’m one of the main reasons the tail end of her senior year is going to look nothing like what we’d been planning since elementary school.

“Thao is moving back across the hall.” She rolls her neck the way she always does after a grueling bassoon session to get the tension out.

“And I’m not even there to help you booby-trap your house like we did in fifth grade! What kind of crap friend am I?” I laugh around the next words because the idea of Thao being anything but a nose-picking cretin is hilarious. “Maybe he’s changed since you last saw him? Or maybe your parents won’t make you two hang out every time they get together. I mean, you’re not little kids anymore. You have a life. Thao probably does too. If you count sneak-attack farting on people a life...”

“That’s right.” Ollie nods enthusiastically. “I do have a life. A life that does not involve disgusting boys who think it’s cool to squirt milk out of their eyeballs.”

I gag at the memory. “I’m telling you, I became lactose intolerant right after that.”

We both crack up remembering gross Thao.

“You know I want to talk to you for a jillion hours, but Darcy gave us a paper assignment. Already. I can’t believe him. Will you be able to talk later?” She eyes the phone hopefully.

Darcy. My favorite teacher. Ollie’s too. She’s pissed because she can’t charm him out of giving actual work-based assignments instead of the fluffy busywork so many other teachers tend to assign during the last half of senior year. Well, giving her actual, work-based assignments. I live in a Darcy-free world now. All I have is Ma’am Lovett.

“Love you, doll. We can chat all night if you call later.” I don’t cry when I disconnect with Ollie, I don’t cry when I look around at the institutionally bare walls of my room, and I don’t cry when I struggle to get into my complicated, strappy bikini, which is as frustrating as playing Chinese jump rope.

I walk through the echoey house. It’s got all the mundane architecture and lack of character you can expect from a last-minute rental in suburban Georgia. The tiny amount of furniture we brought from New York didn’t begin to fill this place, so Mom set up an order from the local furniture store. Even with a truckload of brand-new couches, coffee tables, rugs, and paintings, it’s surprisingly hard to fill three thousand square feet of house with stuff when you’re used to living in an apartment one-sixth that size.

Even though I know I could never call this place home, I wonder who might someday. And I feel bad for them. Though the future owners do get a pool. That’s pretty rad, to just walk out of your house and—blam—there’s a pool.

That you can swim in.

In January.

I guess this place isn’t all bad.

It still blows my mind, because private pools are like unicorns where I come from. Mom tried to use the pool as incentive to get me to like the idea of coming here. Because leaving a city full of culture and art and beauty and ferocious ambition can so be made better with a concrete hole filled with chlorinated water.

I expect the backyard to be serenely empty when I turn the corner, and nearly have a heart attack when I run into a random stranger holding a hose.

“What are you doing in my backyard?” I yell, taking an aggressive stance and gripping my phone hard in case I need to chuck it at his head. Or call 911. I scan the yard for weapons and notice a pool skimmer the cleaning service left on the patio. Maybe I could smack this guy into the water if he tries anything funny?

“’Scuse me. So sorry. I didn’t realize the renters already moved in.”

The voice drawls rough, quiet...familiar. Where have I heard it before? The half-naked male attached to it is practically ripping new armholes in his T-shirt in an attempt to cover up.

I relax my stance and realize he’s not some hulking intruder, but a freaked-out guy about my age, and the T-shirt he’s putting on backward reads Rahn Lawn Care and Maintenance.

“Most days my grandpa and cousin’d be out here during the day, so as not to disturb y’all. I jest head out to the places where there’s no renters in yet. Your house was on my list. Sorry ’bout the inconvenience, ma’am. And about working with my shirt off. Rahn Lawn Care and Maintenance strives to provide professional service, and I apologize if I made you uncomfortable, ma’am.”

He sounds like he’s reciting lines from the HR handbook I had to sign when I worked at the local Y last summer.

“I promise I won’t report you to your boss if you promise to stop calling me ma’am.” When my joke leaves him looking extra terrified, I snort, pull out my sunscreen—SPF 50—and plop onto the nearest lounge chair. “Dude, chill. Seriously, it’s cool. I took my first life-drawing class when I was twelve. Trust me, I’ve seen my fair share of naked guys. I’m not a prude.”

He manages to yank the T-shirt—neck all stretched from his crazy flailing—right side around and get both arms through the sleeve holes. “Uh, cool. I’m Doyle Rahn. Pleased to meet ya.” He holds out a hand.

I shake it, and dirt from his fingers muddies my sunscreen. “Doyle? I’ve never met anyone with that name before. I like it. I’m Agnes. Agnes Murphy-Pujols.”

“Pujols?” His wide, white grin contains just the slightest twisted tooth here and there, and it sends an electric pulse through me. Unexpected, but definitely nice. “Like Albert Pujols?”

“I don’t have any Alberts in my family.” I squint up at him, his head haloed in the sun. He has blond hair that’s just this side of being strawberry, and freckles that have almost melted into a tan.

“Too bad. He’s pretty much the best pure hitter of all time.” Doyle squats down next to what I guess is supposed to be one of the many “shade trees” the real-estate woman kept squawking about. I hate when people say one thing when they mean another. Like, if you mean shriveled, leafless sticks, don’t say shade trees.

“Ah. Baseball. My father is a Caribbean studies professor who lives in France, and my brother is hard-core into soccer. Like, he insists on calling it football when he’s in the States even though he knows it’s confusing.” I think on that for a second. “Huh. I wonder if he does that because it’s confusing. Jasper’s a weird guy like that. Anyway, not much baseball watching going down at my place. But my dad’s where the Pujols part of my name is from, and the DR is pretty famous for baseball players, so, who knows? Maybe I should pay more attention to baseball.” Doyle’s examining the dried-out stick so intensely, I swear he’s doing it to avoid examining me.

“You should. Watch baseball, that is. Actually, you should play baseball. We get a killer game goin’ most Friday nights in the far field back there. You could come ’round if you like. Your brother too.” He nods over his shoulder, and, even with my amazing internal compass, I have no clue where “back there” could be. Someone’s backyard? The empty woods that line the neighborhood? The community office lawn?

“Actually, my brother lives in Paris with my dad,” I blab. It’s weird how sweet it is to talk to a normal person about normal things in my life. Like what a jerk my irritating brother, who I miss a ton, can be. “My brother is one of those guys who ties a silk scarf around his neck like Freddie from Scooby-Doo because he thinks it’s fashionable. He enjoys eating animal organs and watching really depressing documentaries—basically he’s more Parisian than most French citizens.”

“Yeah?” Doyle’s gaze settles on me with a laid-back comfort. Like he could look all day.

I flap my hand in front of my face like a makeshift fan. Was there some kind of sudden solar flare?

“Yeah.” I reach back and lift my hair, damp with sweat, off my neck.

“You ain’t wantin’ to move to Paris too?”

I cackle. “Nope. No way.” I should stop while I’m ahead, but this guy is listening to me. Complete attention. Damn that’s highly attractive. The most explosive arguments Lincoln and I got into before we broke up had to do with the way he seemed to look right through me, the way I felt like I had to fight for every scrap of attention he tossed my way. It really hurt because we’d been friends before we dated, so it wasn’t like I was just losing my boyfriend. I was losing one of my best friends. But Doyle is one hundred percent invested in what I’m saying, so I ramble some more. “First of all my French is awful. Second, the French are, how should I say it...? Les Français sont bites.”

“Sounds fancy.”

“I just said, ‘French people are dicks.’”

The laugh catapults out of his throat so fast, he half chokes on it. It’s nerdy to laugh at your own joke, but I do it anyway. There’s been an alarming lack of laughter in my life lately.

“So, what about you? Do you have any siblings who irritate the crap out of you?”

When he chuckles, the skin over my ribs tingles like I’m being tickled. “I sure do. I got an older brother who’s a marine. Proud as hell of him, but it ain’t exactly easy living with a decorated combat vet.” He dips the tips of his fingers into the soil at the tree’s roots and stirs it into a shallow pattern of spiraling furrows that make me think of those Buddhist sand gardens.

“Does he have PTSD?” I’m not sure if I’m being direct or nosy. I hope I’m not overstepping. Ollie and I did a Civics project on PTSD at Newington, so I know the facts but have no real experience with the horrors of it.

“PTSD? Nah.” Doyle scoops up a tiny mound of dirt and sprinkles it back on the roots. “Lee’s one of them guys who was born a natural soldier. He’s a leader, he handles stress real well, he’s always got a plan, thinks on his feet. One time we got lost out hiking in the woods overnight when Lee was only ’bout ten or so. I was jest a little kid. Lee built a lean-to, caught us some fish to eat, made a fire... He near burned down half a nature preserve, but that’s what led the rescue crew to us. I was crying so hard when they found us, but my brother was cool as can be. He got a medal from the sheriff, and, man, it blew his head up so big. He was... What’s the word? A bite?”

I love the way his accent coils softly around the rude French word. “Brothers are annoying as hell, but Lee sounds like a great guy to have around in an emergency. My brother would have known every statistic about how close we were to death and had a panic attack.”

Doyle’s eyebrows, lips, and dimples all lift up when he smiles. I’ve never seen a smile change a whole face that way. “Problem is, Lee got used to being the boss, and he forgets I’m his brother and a civilian, not some jarhead in his platoon. But my grandparents won’t hear it when it comes to him. They tell me to grab Lee’s laundry, and if I decline, my granddad says, ‘Your brother puts his life on the line for this great nation. You show some respect and pick up his dirty socks.’ I don’t sass my granddad anyway, but that’s some hard logic to argue.”

“So you live with your grandparents?” My guard must be way, way down because I swear I planned to keep that thought in my head, but there it is, sprung from the trap that is my flapping mouth. Maybe I’m relaxing after so many months of watching what I said around Lincoln. “I’m just asking because I considered going to live with my abuela in New York.”

“Huh. Yeah, I’ve lived with them since I was in elementary school.” He leaves it at that, and some instinct tells me not to push. “How ’bout you? Were you just so ready to come down here and soak up all this sunshine?” He holds his hands out at his sides like he personally ordered the blazing heat that surrounds us.

“Ha! No. The snow and ice of the north match my cold heart.” I bat my lashes and am pleasantly shocked when his grin widens even more. “Her place was a super long commute from my school.” I hesitate before I say more, but there’s something about his face that I trust. For once I don’t shut down and pull back. “She’s also scary strict. Like, super Catholic, gets up at dawn to hit the rosary, full rotation, every morning, Bible class at her place every week, having Father Domingo over for dinner every Sunday night... Just not the end of senior year I was looking for.”

“So you didn’t want to sign up for the convent experience?” The laugh that starts from his mouth doubles back on itself. “I meant... ’Cause your grandmother is a Catholic... Not the whole vow of chastity thing,” he says in a garbled rush.

I get the feeling Doyle’s as uncomfortable tripping over his words as I am opening up.

“No worries, I get it. And, yeah, the cloistered life isn’t for me. At all.” The deep pink blush that’s building under his stubble is adorable. “So it’s just you and Lee and your grandparents?”

I’m employing polite conversation diversion to steer us into less embarrassing territory, but something in the question makes Doyle’s features harden.

“And my little brother, Malachi. He’s at Ebenezer too, but you prolly won’t see him around. He stays back in the computer lab with his friends all day every day. Think he might be allergic to sunshine and fresh air.” The best way to describe Doyle’s expression is perplexed. It’s probably the same way my face looks when Jasper tells me he’d rather watch a documentary on spelling bees than the latest Marvel movie.

“So three guys in one house—wait, no, four if you count your grandpa—”

“Actually, it’s five.” When I greet that number with shocked silence, he explains, “Brookes, my cousin—his mama got remarried and he and his stepfather don’t see eye to eye. And his stepfather gets mean when people don’t see things his way. I guess my grandparents’ place is kinda a home for wayward Rahn children. We all figured, what was one more bunk bed, plus Lee’s only around when he’s on leave, so it’s a lotta...”

He waves his hands around like he’s looking for the words to fill in the blank.

“Dirty boxers? Farts? Package adjusting?” I rapid-fire guess.

For a second Doyle stares at me, eyes and mouth wide-open. Then he starts to laugh, hard, and I join him. We both laugh until we’re buckled over.

“Geez, I was gonna say, ‘it’s a lotta testosterone,’ but I guess you got the point across your way jest fine.” He balances easily on the balls of his feet despite his clunky boots. “People ’round here hardly ever come out and say the first thing that pops in their heads.”

I wince. One of the last fights we had, Lincoln told me, You know you don’t have to say every thought that goes through your head out loud, Nes. You need a way bigger filter between your brain and your mouth. I guess that’s the consensus, then.

“Yep, I’ve heard that before.” He tenses up at my tone like he felt a chill in the air. “My big mouth gets me in a lot of trouble. Probably best if you steer clear.”

“I never did have patience for people who play it safe.”

The ice wall I was rapidly constructing around myself thaws.

“Fair enough. But now you can never say I didn’t warn you.”

“Most’ve my favorite things come with a warning.” He clears his throat. “So, we’re short a second baseman since Marnie Jepson moved, and we need someone like yourself. Someone who can call a whole country dicks in their own tongue. Whatta you say? You got a mitt?”

“Nope.” And I plan to leave the discussion right there. Because, seriously? Baseball? It’s very sporty middle school, and so not my thing. But I like the sloppy-slow way Doyle talks—I wonder if he plays ball the same way he speaks. And once I start wondering about something, I have to go with it until I know for sure. Damn my curiosity. If I were a cat, I’d be dead nine times over. “You have an extra mitt?”

He nods and smiles down at a jug of blue stuff he’s now pouring on the roots of the “tree.”

“I do. Wouldya like me to bring it over Friday night?”

For one cold thump of my heart, I think I shouldn’t take this guy up on what might be a date. The last guy I dated messed with my head so badly, I wound up fleeing the state. Then I get annoyed with myself. Sure, Doyle is super attractive, but I’m a girl who’s learned the hard way how to be careful with my heart. This is one single game of baseball, not a promise ring. And I’d like to have some fun with a guy—no, a person—who clearly likes me for myself, not some censored version of me.

I need a friend, and Doyle seems like he might be a really good option.

On top of that, this is all very 1950s’ date-night adorable. “You know what? I would like you to.”

He looks right at me, no smile, no niceties. Just a bald, hungry look. “Cool.”

My guts pull in all different directions. “So, are you, like, the ambassador of Southern hospitality or something? Because you’re the first nice Southern person I’ve met.”

“What? You didn’t like Lovett?” His long fingers cap the jug, and my arms and legs inexplicably tingle.

“You’re in my English class?” It finally clicks, why I recognize his voice. “You schooled that guy, Alonzo, in geography.”

Doyle rolls his eyes. “Hell, a preschool baby could school that ding-dong. He’s a good guy though. Friendly.” He screws his mouth to one side. “I know some people can be chillier than a Yankee winter ’round here.” The way he chuckles when I almost sputter lets me know he’s teasing me. “Not a whole lotta tolerance for anyone who don’t fit in right away.”

I’m not usually embarrassed by much, but I still feel like an idiot over the spectacle I made fumbling through that class. But Doyle seems like a good ambassador for all things Southern, so I straight ask him about something that’s still bugging me.

“What’s with the ‘ma’am’ thing?”

He squats back on his heels and cocks his head, owl-like. “You know... You say ‘ma’am’ or ‘sir’ when you speak to your teachers—to any adults. I thought you were jest raggin’ on Lovett. She’s all bark, I guarantee you. And she likes smart-asses better than kiss-asses, so you’re gonna do fine.”

“I never called any of my teachers ‘ma’am’ or ‘sir’ back home.” I blow out a breath. “I thought that was military-school crap. Is that the rule, like, hard-and-fast? For every teacher?”

He nods again and pulls off his ratty ball cap to wipe the sweat off his forehead. His eyes are so blue, they’re almost a light purple. Adorable.

“Every adult. If you don’t want them to think you’re a total punk. You lived in New York City all yer life?”

“Yep. Brooklyn, specifically. A haven for punks of all varieties.” I smile when his face goes slack. “Is New York City, like, the scariest place in the world to everyone here? Because every single person makes that exact face when I talk about Brooklyn.”

He puts the ball cap back on, shadowing those pretty eyes, and picks up the jug. “Jest exotic as hell. Most people ’round here’ve never left the Lowcountry. And don’t want to.”

“Yeah. I get that vibe.” I probably shouldn’t bring up the fact that, when I’m not at home with Mom, I’m at my father’s apartment in Paris or my cousin’s house in the Santo Domingo in conversation here. People might have heart palpitations and pass out.

“Not me though.” His adamant declaration interrupts my stereotyping thoughts.

“No?” I’m instantly more curious about Doyle now that I know he might want to escape this place. It’s like finding another inmate to help you chip a hole through the concrete walls of your cell.

“My grandparents took me with them to Maui last year. My granddaddy was stationed there when he was a marine, and he really loved it, so they took me and my brothers. It was pretty amazing. Speaking of them, I better get going. My grandmother will beat my ass if I’m late for supper.” He stands up and brushes the dirt off the knees of his Dickies, and I feel a tug of regret.

Because I like talking to him. My FaceTime sessions with Ollie are always great, but I’ve been hungering for real-life human interactions, and Doyle’s already twisted my expectations a few times. I like the way he’s surprised me.

“See you in class tomorrow.” I turn over and notice that he gives my cherry-red bikini a second and maybe a third look. I tip my sunglasses down and smile at him. “Aloha, Doyle.”

His laugh is equal parts sheepish and pleased. “Aloha, Agnes.”

“Nes.” It jumps out of my mouth before I’m ready for it.

Nes is what my friends call me. My standards are dipping low if I consider Doyle a friend after only a couple minutes of conversation. But I guess desperate times and all that...

“Aloha, Nes.” He hesitates, then points to the tree. “Do me a favor? Water her when the sun dips? Jest a trickle outta the water hose for fifteen, maybe twenty minutes to get a good soak going.”

I slowly raise one eyebrow. “Doyle? I hate to break it to you, but that tree is dead. It’s kindling. A lost cause. Have some mercy and let it die a dignified death.”

His fingertips caress a clump of light green baby leaves barely clinging to life. “I like to root for the underdog. See you tomorrow in class.”

Ah right. Before the awkwardness of baseball, there will be the awkwardness of school. Lovely.

I make a point to not watch Doyle’s tall, rangy self saunter away from me.

I come so close to succeeding...

At the last second, I drink him in, then flip over and drag my phone close. My idiotic traitor brain actually thinks about calling Lincoln.

The boy who’s been my best guy friend since we were twelve.

The boy who gave me my first kiss under an old oak tree.

The boy who broke my heart when we were seventeen.

Or the boy who only loaned me his heart so he could take it back eventually, while I gave him mine on a silver platter, free and clear so he could shred it into tiny pieces. Dumb. So dumb.

I toss my phone to the side and throw an arm over my eyes, wondering whose bed Lincoln will be in while I’m standing on second base this Friday. Guilt shoots through me when I remember Mom planned on the two of us going to Savannah on Friday after I got home from school so we could stroll through the art museums downtown and maybe check out the local performing arts college’s production of Grease. I’m torn between wanting to hang out with my mother doing things we love together like we used to and holding tight to a lot of pissed-off anger over the way she screwed things up for us. The betrayal that still cuts deep won’t magically disappear just because we’re both excited to see some Helen Levitt photographs and bop along to “Greased Lightnin’.” Everything is too complicated.

Except baseball.

Playing baseball is definitely easier than dealing with the whole sordid mess of a relationship I currently have with my mother. I roll back onto my stomach, and baseball and cheating and Hawaii and Sandra Dee all invade my dreams as I fall asleep in the oven-hot afternoon of my strange new life.

THREE (#u4b8ddb2a-06a8-5550-9d97-0fa8601bb316)

“Agnes!” Mom’s on the patio in her favorite pencil skirt and silk blouse, her uniform for lecture days. “You’re a lobster!”

“Wha—” I wipe the drool off the side of my face and try to push myself up, but my skin feels tight and puckered. “Coño! I actually used sunscreen, I swear.”

“Honey, you’re half-Irish. Sunscreen is nothing but a cruel joke.” She runs her fingers over my tender skin. “Come in. I have aloe. And I picked up Chinese on the way home.”

How many times have I had to explain to my more clueless pale friends that dark-skinned people can and do burn? What’s that saying about heeding your own advice...?

“I don’t get it. Why do my genes put me through this trial by fire every summer? Jasper can be out in the sun for hours and this never happens to him,” I growl, limping in and sitting on a stool at the counter. Maybe my skin is reacting so badly because it wasn’t expecting this kind of sun exposure in January. I say a silent prayer it won’t be blotchy and peely tomorrow.

My mother pushes a carton of cooling Buddha’s delight my way. We’ve already eaten at the one and only Chinese food place in a thirty-mile radius so often, they can recite our phone number from memory based on the sound of our voices when we call to order.

“You aren’t in New York anymore, Aggie. As far as your brother’s ability to endure the sun goes, I actually wish Jasper was more careful with sunscreen. Just because he can be out for hours without it doesn’t mean he should. Skin cancer is nothing to play around with.” My mother dabs aloe on my skin, and I suck air through my teeth to manage the pain that stings through the cool. “Plus you freckle.”

I know the go-to image of an Irish lass centers on a redhead with alabaster skin and cinnamon freckles in a wool sweater standing by the Cliffs of Moher, but...

“Right. I’m Irish,” I say through a mouthful of overcooked vegetables I just slurped off my chopsticks.

“But my family is bone-white pale, not freckly. I think your freckles are from your Dominican half.” I look down at my mother’s pale fingers tangled with my dark ones. I love that we have the same oval-shaped nails and double-jointed thumbs. I love what I inherited from her, and I love what’s different about us. And that makes me miss how close we used to be. How close my whole family used to be.

When I was a kid I used to spill out my colored pencils and hold them close to my family members so that I could get the color of their skin just right in my drawings. After a long, dark New York winter, mine would mellow to a dark golden tawny, a few shades darker than my mother’s at the end of summer. By contrast, after a summer spent at our communal family beach house in Santo Domingo, my skin would be a light sepia with a spattering of umber freckles. I’d admire myself in the full-length mirror in the bedroom I shared with half a dozen of my girl cousins, each one of us a different shade of gorgeous and proud to announce it. One of the first slang phrases I picked up in the DR as a kid was hevi nais, which my cousins said about anything and everything—cute new outfits, beautiful hairstyles, too-tall sandals, our sun-warmed skin. It basically means “very nice,” and it’s the kind of casually confident phrase that still makes me feel beautiful and strong in my own skin. I loved the fact that while everyone else in school had their twenty-four pack of Crayola colored pencils, I had my set of seventy-two Prismacolor Premiers with a range of russets and taupes and ochers for my family pictures.

“Can’t a girl define her own cultural heritage?” I snap, annoyed that nothing feels easy with my mother anymore. Not even a conversation about something as simple as freckles.