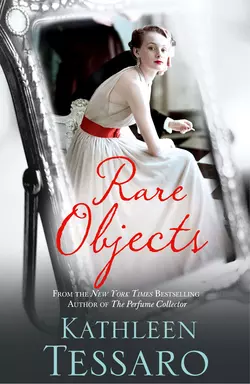

Rare Objects

Kathleen Tessaro

The stunning new novel from the New York Times bestselling author of The Perfume Collector.‘Beautifully written… wonderfully absorbing with a clever twist in the tale’ Isabel Wolff, author of GhostwrittenMae Fanning seizes on a job at a tiny, exclusive Boston antiques shop as the fresh start she desperately needs. It opens a window to new world, one peopled with rare and rich characters. But the day that enigmatic socialite Diana van der Laar walks in, Mae’s hidden past returns.As a moth to a flame, Mae is unable to resist Diana’s heady, seductive glamour and glittering life. Yet, like the rare objects in the shop, very little is what it appears – Diana included.Moving from Jazz-Age New York to Boston in the grip of the Great Depression, Rare Objects is a rich and gripping story of what it means to reach for a braver, bolder life.

Copyright (#ulink_e005d595-fca7-5e1e-b0e5-5f4cb46b9bbf)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Copyright © Kathleen Tessaro 2016

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016. Cover photographs © Condé Nast Archive/Corbis (woman); Mariko Abe/Getty Images (mirror).

Kathleen Tessaro asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007419869

Ebook Edition © June 2015 ISBN: 9780007419869

Version: 2017-11-29

Dedication (#ulink_703f4cdb-a945-59f1-add1-0bb7361ea3c4)

This book is dedicated to my dear friend ROBERT TROTTA, whose remarkable character has forever shaped the fate of my son for the better and given me proof time and time again of true heroism in this world. I am beholden to you, sir.

Epigraph (#ulink_535c6e20-1b6a-5c60-bbab-bc550ddc0a76)

A man’s character is his fate.

HERACLITUS, Fragments

Contents

Cover (#u85d5e347-faee-524d-97ff-64b90b20eec8)

Title Page (#u3c6a07ae-62d3-570b-b4c5-ee3c084dc1c0)

Copyright (#u121ea166-dee2-58a6-86d1-8cfc0e74765a)

Dedication (#u8b0c0325-bab9-5ebd-a3e6-39f749049e2d)

Epigraph (#u87379cce-be6d-5353-a138-b58e9e482663)

Part One (#u958d7983-0f67-57f6-8f17-50f1ea2b02e0)

Boston, February 1932 (#u2e518a70-a1cc-54e0-af3d-dddc84ceac9c)

Somewhere in Brooklyn, November 1931 (#u01e97c94-72f5-5acf-a64f-d5bd13ca374c)

Boston, February 1932 (#ub27c27fa-6139-589e-a5ae-9a0a904bb21d)

Binghamton State Hospital, New York, 1931 (#ua23dcdd2-b783-5b42-b6f5-b13c8e460988)

Boston, February 1932 (#u5e3bc3af-0441-5cab-a0fa-02576377fa2e)

Part Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Reading Group Questions (#litres_trial_promo)

Author Q & A (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Kathleen Tessaro (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Looking back is a dangerous thing. I’ve spent much of my time studying other ages, searching out the treasures of ancient worlds, but I’ve always found it best to move forward, eyes front, in one’s own life. Hindsight casts a harsh, unforgiving light, and histories too tender and raw are stripped bare of the thousand shadowy self-deceptions that few of us can afford to see ourselves without.

But even the most conscientious of us can forget. The past dangles before us, as innocently as a loose thread from a sleeve. For me it began with a few lines in the local newspaper.

“Renovation works scheduled to begin at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.”

It had been years since I’d been there. I’d thought of going, many times, and even gotten so far as to be standing on the front steps before something stopped me. I suppose the place held too many memories, maybe even a few ghosts. Is there anything more haunting than the ambitions of youth?

But one of the great myths of age is that it brings us wisdom. It had been too long, I decided, folding the paper. This time I will knot the thread, tie the untidy end of my past or cut myself free of it.

And so, like Orpheus in the underworld, I talked myself into turning back and looking one last time at what I shouldn’t see.

I made the mistake of going on a rainy Saturday afternoon in March. The museum was full of families with small children careering from one room to another. They’re encouraged to touch everything these days—sticky handprints on all the glass cases.

I managed to avoid being tackled by toddlers and found my way to the Art of the Ancient World wing. The room I was looking for was sealed off with a red velvet rope and a sign that read “Closed to the Public.” I stepped round the rope, behind the sign, and into the abandoned gallery.

It was cool inside, and wonderfully quiet. There were tins of unopened paint and folded dust sheets, a few cigarette butts floating in some empty Coca-Cola bottles, but no work had actually begun. They hadn’t moved any of the displays yet or stored away the artifacts. Above the marble arch of the entrance it read “The Treasures of the Golden Age” in gilded lettering. I could see from where they’d constructed the scaffolding that they were probably planning to rub it out.

The mural was still there, though faded and cartoonish—Greek temples and dancing nymphs, satyrs playing flutes. I was surprised to feel a nostalgic twinge of sentimental affection for it, even though I hadn’t liked it at the time. Aging does that; it makes you amenable to far more ambiguous feelings and opinions than the inflexible black-and-white thinking of youth.

I walked past the statues of the mythical brothers Kleobis and Biton, frozen in rigid perfection, and paused by the vase and plate by the Harrow Painter, the archaic red-figure master. I even read the plaque beneath them, although I already knew what it said.

I remembered the first time I’d seen them, and the thrilling, slightly terrifying anticipation came flooding back, like déjà vu. Among the finest aesthetic accomplishments of their age, they’d been entrusted to my care one strange, ill-fated evening.

How young I’d been! How desperate and frightened and arrogant, all at the same time!

I continued, moving from case to case.

And then there it was, in one of the cabinets along the far wall: the black agate ring. I wasn’t sure it would be there; I just had a feeling.

Even after all these years the sight of it made my skin go cold.

“Excuse me, madam?”

The voice startled me. I turned.

A young guard was hovering tentatively by the entrance as if he didn’t dare disobey the sign.

“Yes?”

“I’m sorry, madam, but this gallery is closed.”

I feigned surprise. “Really?”

He nodded. “Can I help you? Are you lost?”

I didn’t answer right away. Instead I looked round one last time. The thread of my past unspooled before me—memories, dreams, and regrets.

“Do you need some help?” he repeated, louder this time.

I shook my head. “No, thank you.” And lifting my chin, I pulled myself up to my full height, tucked my handbag under my arm, and marched past him. It’s a trick I learned from my mother—when in doubt, act like you know what you’re doing, and you’ll be treated like you do.

And of course, if you can convince others, there’s a chance that someday you might just be able to convince yourself.

Part One (#ulink_231b598c-fe44-5d83-965f-5f9e8eac783a)

BOSTON, FEBRUARY 1932 (#ulink_c3b166e0-a11e-524a-b30a-dc00d75b3fec)

I opened my eyes.

It was still dark out, maybe a little after six in the morning. Lying on my back in bed, I stared at the ceiling. I could just make out the wet patch in the corner where the roof leaked last spring and the wallpaper had begun to peel away—pale-green wallpaper with pink cabbage roses my mother had put up when we first moved in, over twenty years ago. At the time, it seemed the epitome of feminine sophistication. Outside, the rumble of garbage trucks drew closer as they made their way slowly down the street, and I could hear the faint cooing of the pigeons Mr. Marrelli kept on the roof next door; all familiar sounds of the city coming to life. They should’ve been reassuring. After all, here I was, back in my own room; home again in Boston. But all I felt was a dull, gnawing dread in the pit of my stomach.

I couldn’t sleep last night. Not even Dickens’s Great Expectations could still my racing mind. When I did finally drift off, my dreams were disjointed and draining—full of panic and chaos, running down endless alleys from some black and terrible thing, never fully seen but always felt.

I hauled myself out of bed and put on my old woolen robe and slippers, navigating the narrow gap between the end of the bed and the stacks of books—I collected secondhand editions with broken spines bought from street stalls or selectively “borrowed” from the library: Jane Austen, the Brontë sisters, Dickens, Thackeray, Collins. Great heavy editions of Shakespeare and Milton, Yeats, Shelley, Keats. “You’ve read them already, why do you need to keep them? All they do is take up space!” my mother complained. She was right—there was no room for anything, not even a chair. But where Ma saw only old books gathering dust and smelling of mildew, I found comfort and possibility. Other worlds were within my grasp—better worlds full of rewarded ambition, refinement, and eloquence. I clung to them as a pilgrim whose faith is proportional to the extremity of their need clings to a relic or a prayer.

Shuffling into the bathroom, I paused to press my hand against the radiator in the hallway. Stone cold as usual. I don’t know why I kept checking. The triumph of optimism over experience. Or good old-fashioned stubbornness, as my mother would say.

Turning on the bathroom light, I blinked at my reflection. It was still a shock. I used to have long hair—thick, copper red, and uncontrollable, a dubious gift from my Irish heritage. Now it was cropped short, growing back at least two shades darker in deep auburn waves. It made my skin look even paler than usual. I put my finger on the small cleft in my chin, as if covering it up would make it disappear entirely. It always struck me as a bit mannish. But I couldn’t hold my finger there forever. Bluish-gray shadows ringed my eyes, the same color as the irises. My eyes looked huge—too large, too round. Like a madwoman’s, I thought.

I splashed my face with cold water and headed into the kitchen.

My mother was already up, sitting at the kitchen table reading the paper and smoking her morning cigarette. Even in her curlers and dressing gown, she sat upright, straight back, head held high, at full attention. Regal. That was the best word for it. Apparently even as a young girl she was known as Her Majesty in the Irish seaside town she grew up in. It was a nickname that fit her in more ways than one.

The rich aroma of fresh coffee filled the air. It was a tiny room, mostly taken up by the black cast-iron stove recessed into the mantelpiece. On one side there was a built-in dresser and just enough room for a small wooden table and a couple of chairs. Two narrow windows looked out over the street below and a clothes airer was suspended from the ceiling, to be lowered with a pulley. The rest of the neighborhood used the public lines hanging between buildings, but not us. It was common, according to my mother, and that was the last thing we Fanning women wanted to be.

Ma frowned when I walked in—anything out of the ordinary was cause for suspicion. “What are you doing up this early?”

“I couldn’t sleep.” I checked the gas meter above the sink. It was off. “It’s cold,” I said, knowing that I was asking for trouble.

She shot a long stream of smoke at the ceiling, a combination of exhaling and a world-weary sigh. “When you get a job you can stuff the meter full of quarters. Now eat. You need something in your stomach, especially today.”

“I’m not hungry.” I poured myself a cup of strong black coffee and sat down.

The heat, or lack thereof, was always a sticking point between us. But since I came back it had become the central refrain of almost every encounter. It’s funny how some arguments are easier, more comforting, than real conversation.

I looked round the room. Nothing had changed except for the Roosevelt campaign leaflet pinned on the wall with the slogan “Happy Days Are Here Again.” Otherwise it was all just as I remembered it. Above the stove were three books—Mrs. Rorer’s New Cook Book: A Manual of Housekeeping, a copy of Modes and Manners: Decorum in Polite Society, and a small leather-bound Bible—our entire domestic library. Next to that, displayed on the dresser shelves, were my mother’s most precious possessions: a photograph of Pope Pius XI, a picture of Charles Stewart Parnell of the Irish Nationalist Party, and in the center of this unlikely partnership, a small wooden crucifix. Below, my framed diploma from the Katherine Gibbs Secretarial School took up the entire shelf. And on the bottom a genuine blue-and-white Staffordshire willow-pattern teapot with four matching cups and saucers sat waiting for just the right occasion, a wedding gift brought all the way from Ireland.

“So”—Ma decided to get straight down to business—“what are you going to wear today?”

“My blue dress. Maybe with the red scarf.”

“Really.” She sounded distinctly underwhelmed. “That dress isn’t serious enough.”

“Serious enough for what? It’s only an employment agency.”

She ignored my tone, folding the newspaper neatly. It would be saved and used again—to line the shelves of the icebox or wash windows, maybe even to cut out patterns for clothing. I used to wonder what it felt like to waste something; as a child I couldn’t imagine anything more delicious or sinful than the extravagance of throwing things away. I’ve wasted a few things since then; it’s not as liberating as I imagined.

Ma made me an offer. “I’ll tell you what, Maeve. You can borrow my gray wool suit. I pressed it last night, just in case.”

She said it as if she were handing me the keys to the city.

And in her mind, she was.

Ma worked in a high-end department store called R. H. Stearns in downtown Boston. She’d been there years in the alterations department, working as a seamstress. But her real ambition was to be a saleswoman. More than anything she fancied herself a fashion adviser to wealthy women—the kind of society mavens with enough money to buy designer gowns and a different fur for every outfit. To this end she wasted precious quarters on copies of Vogue and McCall’s every month, poring over them, memorizing each page. She’d bought the gray suit years ago when she first began applying for a sales position, but they passed over her year after year. Perhaps it was because she was so skilled a seamstress, or perhaps because they thought she was too old, at forty-three, or maybe too Irish. But in any case the gray suit, the proud uniform of her future self, still hung in her wardrobe, outdated now.

“The blue dress fits better,” I told her.

“This is a job interview, not a date.” She was hurt. I could hear the wounded pride in her voice, as if she’d just proposed, been turned down, and now had to get up off her knees from the floor. “Also I fixed that hat of yours, the one with the torn net. I steamed it back into shape but in the end I had to take the net off.” She got up, went to the sink. “Where’d you get a hat like that anyway, Maeve? It’s a Lilly Daché! They cost a fortune!”

Trust her to notice the label.

“It was a gift,” I fibbed.

“Well, you certainly didn’t take care of it. And a ‘Thank you’ wouldn’t go amiss.”

“Cheers, Ma.”

She started to wash up.

I stared out the window, pressing my palms tightly against the coffee cup for warmth. Sitting here in the kitchen just before the day truly began, looking out into the darkness, calmed my nerves. The city was shadowy, lit only by streetlamps. But still the North End was already awake and opening for business.

The fruit seller across the street, Mr. Contadino, was setting up his stall, squinting as he cranked open his green-striped awning in the icy wind, the air swirling with snowflakes. He had on a flat cap and a heavy woolen vest under his clean apron, and a pair of knitted fingerless gloves protected his stubby hands. Soon he would light the chestnut stove—a large iron barrel near the shop doorway with a coal fire in the base and fresh chestnuts roasting in the top. He sold them tender and hot in little brown paper bags for a penny. Contadino’s chestnuts were a glowing beacon of civilization in the North End. The smell of the buttery flesh roasting and the delicious combination of cold air and the crackling fragrant heat radiating from the belly of the stove made it all but impossible not to stop as you passed by. Men collected there, speaking in Italian, smoking, laughing, warming their hands. In the morning they held tiny steaming cups of espresso, and in the evening cigar smoke, sweet and luxuriant, billowed around them in clouds.

As Ma was fond of pointing out, Contadino knew what he was doing. That chestnut stove brought him twice as much trade as any other fruit seller in the neighborhood had. “See, the Italians are smart. And they don’t drink. We made the right choice; we’re better off here.”

Here was the North End of Boston. Waves of immigrants had made the North End their home over the years. It had been a Jewish ghetto before the Irish took over, but most had since moved south; it was firmly Italian now. We had second cousins living in the South End, but Ma always considered herself a North Ender, valuing privacy over familiarity. “We don’t have to live in everyone’s back pocket,” she used to say.

“A suit looks more professional.” Ma hated to lose an argument. “Just because you’re not working doesn’t mean you can’t look respectable.”

Respectable was one of Ma’s favorite words, along with ladylike and tasteful. Quaint, old-fashioned words. To me they sounded as relevant as bustle and parasol; faded echoes from another era when good looks, pleasing manners, and modesty were all that were required in the female arsenal. Nowadays, they just made you seem backward.

“I’ll think about the suit,” I told her, watching as Mrs. Contadino, wrapped in a shawl, came out into the cold with her husband’s coat. He waved her away, but she won in the end; he had to put it on before she would go back inside.

Then I remembered what day it was.

“It’s the eighth today, isn’t it?”

I saw her smile. Maybe it pleased her that she didn’t have to remind me. “That’s right. It’s a sign. Mark my words: it’ll bring you luck!”

Underneath Ma’s worldly exterior a superstitious child of Ireland still lingered, clinging to all the impossible magic of the supernatural.

“Do you think?” I swallowed some more coffee.

“Absolutely! You were born at night, Maeve. That means you have a connection to the world of the dead. If you ask for their help, they’re sure to come.” She topped up my cup. “I’ll be going to mass later if you want to join me. I’m sure he’d like it if you came too.”

It had been a long time since I’d been to mass. Too long.

I looked out at the pale gray dawn, bleeding red-orange into the sky. “Go on, Ma, tell me about him,” I said, changing the subject. It was also a tradition, something we did every year on the anniversary of my father’s death. And who knew, maybe today it would make a difference; maybe against all reason, my dead father would lure good fortune to me.

“Oh, Maeve!” She shook her head indulgently. “You know everything there is to tell!”

Every year she protested—not too hard.

“Go on!”

And every year, I insisted, for old times’ sake.

She paused, teasing the moment out like an actress about to play a big speech. “He was a remarkable man,” she began. “A graduate of Trinity College in Dublin. A true gentleman and an intellectual. Do you know what I mean when I say that?” She took a long drag. “I mean he had a hunger for knowledge; a deep longing for it, the way that some people yearn for food or wealth.” She smiled softly, exhaling, and her voice took on a tender, dreamy tone. “It made him glow; like he was on fire from the inside out. His eyes used to burn brighter, his whole being changed when he was speaking on something that interested him, like literature or philosophy. He was good-looking, yes,” she allowed, “but if you only could’ve heard him talk … Oh, Maeve! His voice was a country—a rich green land populated with mountains and rivers …”

She had the gift, as the Irish would say, an ear for language. Her talents were wasted as a seamstress.

“He drew you into other places. Other worlds. He made the obscure real and the unfathomable possible. He would’ve been a great man had he lived. There was no doubt. His brain was like a whip.” She flicked a bit of ash into the sink, pointed her cigarette at me. “You have that. You have a sharp mind.” Her words were an accusation rather than a compliment. “And his eyes. You have his eyes.”

There was just one photograph of Michael Fanning. It sat on the mantelpiece in the front room, a rather startling portrait of a handsome young man staring directly into the camera. His broad, intelligent forehead was framed by waves of dark locks, and his features were fine and even. But it was the fearless intensity of his gaze and the luminous pinpoints of light reflected in his black pupils that drew you in. It was impossible not to imagine that he was looking straight at you, perhaps even leaning in closer, as if he’d just asked a question and was particularly interested to hear your answer. It was an honest face, without artifice or pretension, and as far as I was concerned, the most beautiful face in the world.

I’d never known him. Ma was a widow and had been all my life. But his absence was the defining force in our lives, a vacuum of loss that held us fast to our ambitions and to each other. He’d always been Michael Fanning, never father or Da. And he wasn’t just a man but an era; the golden age in Ma’s life, illuminated by optimism and possibility, gone before I was born. I’d grown up praying to him, begging for his guidance and mercy, imagining him always there, watching over me with those inquisitive, unblinking eyes. God the Father, the Son, the Holy Ghost, and Michael Fanning. In my mind, the four of them sat around heaven, drinking tea, smoking cigarettes, taking turns choosing the forecast for the day.

“What time are you going to mass?”

“Six o’clock. I want to go to confession before.”

Confession.

Now there was the rub. I certainly wasn’t going to confession.

“Well,” I said vaguely, “I’ll see what I can do, Ma.”

My parents met in Bray, a small seaside town in county Wicklow, Ireland. Fresh from university, Michael Fanning turned his back on his family’s considerable resources to teach at the local comprehensive, where Ma was a student in her final year. After a brief and clandestine courtship they married, against both their parents’ wishes, when she was just seventeen. They planned to immigrate to New York, where Michael’s cousin was already established. But he contracted influenza, and within three days was dead. No one from either family came to the funeral.

With what little money remained after burial costs, seventeen-year-old Nora set sail for America rather than turn to her family for help. The only ticket she could afford landed her in Boston, and so I was born six months later, in a tiny one-room apartment above a butcher’s shop in the North End, with no heat, hot water, or bathroom. I was delivered by the butcher’s wife, Mrs. Marcosa, who didn’t speak English and had seven children of her own, most of them kneeling round the bed praying as their mother, sleeves rolled high on her thick arms, shouted at my terrified mother in Italian. When I finally appeared, they all danced, applauded, and cheered.

“It was one of the most wonderful and yet humiliating days of my life,” Ma used to say. “The Marcosa children all loved to hold you because of your red hair. They found it fascinating. The whole neighborhood did. I couldn’t go half a block without someone stopping me.”

She took in seamstress work during the day, piecing together cotton blouses for Levin’s garment factory nearby, and in the evenings she traveled across town to clean offices, taking me with her in a wicker laundry basket, wrapped in blankets. Setting me on the desks, she made her way through the offices, dusting, polishing, and scrubbing, singing in her low soft voice from eight until midnight before heading back across the sleeping city.

But she always hungered for more. And even when she joined the alterations department at Stearns, she’d already had her sights set on moving from the workroom to the sales floor. She enrolled in Sunday-afternoon speech classes from an impoverished spinster in Beacon Hill, taking me with her so that I could learn to enunciate without the telltale lilt of her brogue or, worse, the flat vowels of the Boston streets. I suppose that’s something we have in common—the unshakable conviction we’re destined for better things.

Year after year she continued to apply for a sales position, ignoring the rejections and snubs, refusing to try elsewhere. “It’s the finest department store in the city,” she maintained. “I’d rather mop floors there than anywhere else.” She could endure anything but failure.

Stubbornness is another trait we share.

She still wore the plain, slim gold band her husband had given her on her wedding ring finger, not just as a reminder but also as a safeguard against unwanted male attention.

“Your father would’ve been proud of you, Maeve, getting your secretarial degree.” She took a final drag from her cigarette, stubbed the end out in the sink.

I looked down. “Oh, I don’t know about that.”

“Well, I do.”

All my life, she’d been a medium between this world and the next, advising on what my father would’ve wanted, believed in, admired.

“He had everything it took to really be someone in this world—intelligence, breeding, a good education. Everything, that is, except luck. I just hope yours is better than his.” She sighed.

“What do you mean?”

“Nothing. You’re a clever girl. A capable girl.” Leaning in, she scrubbed the coffee stains out of the sink. “It’s just a shame you lost that job in New York.”

A knot of guilt and apprehension tightened in my stomach. This was the last thing I wanted to talk about. “Let’s not go into that.”

But Ma was never one to let a subject die an easy death if she could kick it around the room a few more times.

“It just doesn’t make sense,” she went on, ignoring me. “Why did Mr. Halliday let you go after all that time?”

“I told you, he’s traveling.”

“Yes, but why didn’t he just take you with him, like he did before? Remember that? You gave me the fright of my life! I didn’t get a letter from you for almost six weeks!”

It was if she knew the truth and was torturing me, the way a cat swats around a half-dead mouse. I glared at her. “Jeez, Ma! How would I know?”

“It just doesn’t make sense. You’ve been his private secretary for almost a year, and then, out of the blue, you’re suddenly out of work and back in Boston!”

“Well, at least I’m home. Aren’t you glad about that?”

She gave a halfhearted shrug. “I’d rather have you make something of yourself. You were on your way in New York. Now you’ll have to start all over again.” Scooping some porridge into a bowl, she set it down in front of me. “I’ll hang the gray suit in your room.”

I gnawed at my thumbnail. I didn’t want porridge or the suit. The only thing I wanted now was to crawl back into bed and disappear.

She gave my hand a smack. “What are you doing? You’ll ruin your nails! Don’t worry so much. With your training and experience, you’re practically a shoo-in.”

I prodded the porridge with my spoon.

My experience.

If only my experience in New York was what she thought it was.

SOMEWHERE IN BROOKLYN, NOVEMBER 1931 (#ulink_a57c50a3-9930-5cdb-b469-36ac3760bdf3)

I was falling, too fast, with nothing to stop me … down, down, gathering speed …

I came to with a jolt. I was sitting on the side of a bed wearing only my slip and stockings—a wrought-iron bed in a cold, dark bedroom. Only it wasn’t my bed or my room.

Suddenly the floor veered beneath me, the walls spinning, faded yellow flowers on the wallpaper melting together. Please, God, don’t let me be sick! I pressed my eyes closed and held on to the bed frame tight.

I had to think. Where was I, and how exactly had I gotten here?

It had been a long, dull night at the Orpheum dance palace on Broadway where I worked. The joint was full of nothing but out-of-towners and hayseeds—guys with little money and lots of expectations. By the time we’d closed and I’d cashed in my ticket stubs, I was ready for some fun. Another girl, Lois, had made a “date” with a customer, and he had a friend … Was I game?

Why not? After all, it wasn’t like I had anything to lose.

I remembered two big men, grinning like excited schoolboys, in New York for a convention and laughing the way tourists do—too easily and too hard, willing themselves to have the best night of their lives. One was reasonable-looking, and the other—well, let’s just say no one was going to mistake him for Errol Flynn or Douglas Fairbanks. But there’s that old adage about beggars and choosers, and tonight I felt like a beggar for sure. The last thing I wanted was to be alone and sober at the same time. So we all piled into a cab. Hip flasks were passed round; I remembered Lois sitting on someone’s lap, singing “Diggity Diggity Do.”

We drove to Harlem, to a place called Hot Feet. There was a band from New Orleans and a chorus line of smooth-skinned Negro girls dressed up with grass skirts and bone necklaces, shaking and shimmying for all they were worth. The moonshine had kicked in by then, and I was feeling a bit less rough round the edges. Lois was sure she saw Oweny Madden and the boxer Primo Carnera at the next table, and one of the guys, the ugly one, forked out for a bottle of real gin.

God, my mouth was as dry as the Sahara! What time was it now? What had happened to Lois?

I tried to stand. My head pounded, my stomach swooned. Easy does it. Not too fast.

Someone shifted in the bed next to me.

Shit. Please don’t let it be the ugly one.

I tried not to look. A face you never saw was a face you never remembered. I’d learned that much in New York.

I eased myself up. My knees were sore, and there were holes in my stockings. I guess I must’ve fallen. Going over to the window, I pushed aside the curtain. The street was residential, narrow row houses with uneven terraces crammed together, lamps glowing eerily over abandoned lots between. I searched for something familiar on the skyline, a bridge or a building, but couldn’t see anything. One thing was certain: I was definitely on the wrong side of the river.

I seemed to remember talk of going to a hotel to carry on the party—someplace like the Waldorf or the Warwick. So why was I stranded in some cheap boarding house in Queens or Yonkers with no idea where I was or how I was going to get home?

The man rolled over on to his side and began to snore. I had to get out of here, before he woke.

Where were my clothes?

I nearly stumbled over something and picked it up. But this dress wasn’t mine.

Then a memory came of the day before. I’d borrowed a dress from Nancy Rae, the girl down the hall at the Nightingale boarding house, where I rented a room. It was Nancy’s good-luck dress, a hunter-green serge she’d been wearing when she landed her job at Gimbles; all the girls wanted to borrow it for interviews. I’d given her a dollar for the privilege and even gotten up early to steam the box pleats of the skirt through a towel to make them crisp and sharp without going shiny. When I finished, they fluttered open like a fan round my legs.

See that’s the thing about luck—it has to be courted. You have to seduce it; reel it in slowly without arousing suspicion. It’s so precious that every tiny thing matters—what you wear, which side of the road you walk on, the tune you whistle, or how many birds you see out the window. Nancy Rae’s hunter-green dress had stood in fate’s presence and felt its light touch. And when fate favors anything, you’d best pay attention.

I’d been working as a taxi dancer at the Orpheum for months, waltzing with strangers night after night for a dime a dance. But when I saw the advertisement in the back of the Herald for “a young woman of exceptional executive secretarial skills,” I knew that my luck was about to change.

So I gave Nancy the dollar, ironed the dress, and set out first thing in the morning with my notebook and résumé in hand.

But when I arrived at the address, a full hour ahead of time, there were already fifty girls ahead of me, lined up around the corner of the office building, all clutching notebooks and reference letters, all looking hungry and determined and ferociously confident. I lasted three hours waiting in the cold before the girl ahead of me, a short brunette with a frizzy permanent wave and a big run in her stocking, turned round and announced, “You know they’re not going to see all of us, don’t you? I’ve been standing in lines for months, just trying to get my foot in the door. I tell you, we’re waiting here for nothing, like a bunch of saps!”

No one answered her. You can be six inches from someone’s face in New York City and they can still stare straight through you, like you’re not even there. But when I looked around, I could see from the other girls’ faces that what she said was true.

Then she leaned in closer. “I know a guy who runs the door on a joint off Lexington. If you sit at the bar and are friendly to the customers, they don’t mind serving you for free, especially if you’re good-looking.”

I didn’t know why she was telling me. Did I look like the kind of girl who was at home on a barstool? I lifted my chin a little so I was looking down at her and sneered, “What of it?”

She wasn’t put off. “Besides”—she jerked her head at the others, shivering ahead of us—“today’s not our day, sister.”

There were an awful lot of us. The line stretched right up the block and disappeared round the corner. And it would be so nice to sit down and get warm. I didn’t have any money for breakfast that morning, so my stomach was playing a selection of squeaky, off-key tunes all on its own.

Still, if they could only see my qualifications, give me a chance.

The poodle-haired brunette wasn’t waiting any longer. “Fine!” She rolled her eyes, the voice of reason in a world full of idiots. “I was trying to do you a favor, but if you want to catch frostbite just to be told thanks but no thanks, that’s up to you!”

“Is it heated?” I’m on the thin side, being warm is something of an Achilles heel for me.

She shot me a look like I was from the backwoods of West Virginia. “Sure it’s heated! And they got free peanuts at every table, as much as you can eat.”

As soon as I stepped out of line, the girl behind me shoved forward like I was all that was standing between her and destiny. I tossed a sad smile her way just to show her I knew better. I was off to be fed and watered for free. I’d graduated from waiting around.

The poodle brunette had a name like Ivy or Ida or Elsa, and once inside the club on Lexington, she told me right where to sit and how to play it. She got us both a basket of peanuts and we ate as much as we could stand before she brushed the shells off the table and swung into action. Hers was an entirely democratic brand of lazy hospitality—everyone was included in its warm glow, but no one was singled out; every guy figured he had a chance. Maybe because of this she was a past master at getting men to buy more rounds. It wasn’t long before the morning slipped into the afternoon and the afternoon into the evening. I probably ate a pound of peanuts that day. Soon it was time to head over to Broadway to begin another shift at the dance palace.

Now here I was, eighteen hours later, tripping over Nancy Rae’s lucky green dress, crumpled in a heap on a stranger’s floor.

My life was full of cracks, ever-widening gaps between the person I wanted to be and the person I was. When I first came to this city, they used to be small enough to laugh off or ignore. But over the past year they’d grown wider, deeper. I’d fallen in one again last night.

This was the last time, I promised myself.

The very last time.

I found my coat in the corner, thrown over a chair. My new hat, the one I’d splurged on when I got my first job, had been stepped on, squashed into a flat felt circle, the black net that had framed my face so charmingly torn and dangling miserably from a few threads.

I got dressed. Unfortunately I’m good at this—navigating creaky floorboards and sleeping men, finding clothes in the dark. It’s a loathsome talent.

All I needed now was my handbag.

I searched the floor, the bedside table, then on the dresser. A watery blue beam of moonlight streamed in from the crack in the curtains. An old-fashioned gold pocket watch and a pair of cufflinks sat on top of it. Next to them was a photograph of a dark-haired woman holding a toddler. Both were smiling—big, wide, foolish grins. “To Daddy, with all our love” was written in a woman’s rounded hand across the bottom right-hand corner.

I wanted to throw up.

The guy in the bed snorted, coughed. I spotted my bag, jammed between the bedposts, and eased it out.

The room was quiet except for the snoring and a gentle ticking sound; a steady march of time.

I picked up the watch. Solid, smooth, and heavy, it had a pleasant, reassuring weight. My fingers closed round it; it fit neatly into the palm of my hand.

Three twenty-three a.m.

Plenty of time to get back to the boarding house and sleep it off before work tonight. Plenty of time to re-iron Nancy Rae’s dress before returning it. Maybe I’d buy a paper on my way home, get a head start on finding another job. That’s what I told myself. But more likely I’d just stay in my room, too ashamed to let the other girls see me coming in at dawn, lock the door, and lie in bed all afternoon, listening to the music of the landlady’s radio seeping through the floorboards. And I’d imagine how maybe soon things would be different; a man would come into the dance hall who was decent and kind or I’d stumble across a real job or maybe finally I’d just give up altogether, go home …

Tomorrow my luck would change. Tomorrow I’d try again.

Only I had to get through tonight first.

I don’t know why I took the watch. Maybe it was just an accident. Or maybe because of the stupid hopeful grin on the woman’s face in the picture, or because of the way the man in the bed smelled like mothballs and sour sweat. Maybe just because it gave me something to hold on to.

I don’t know why. But I did.

And I really wish I hadn’t.

Because after that, things got a lot worse.

New York City was the knife’s edge of opportunity—modern and progressive. A place where a girl could leave her past behind and get a job and a life that really mattered. Every day smart young women with bobbed hair and cherry-red lips poured out of the subway stations at eight in the morning to take over the world, and no one batted an eye. No one cared either when they ended the day sipping cocktails in underground clubs next to their male colleagues.

I told everyone that I went to New York City because I didn’t want to end up just another pair of hands in a typing pool. Sharp, efficient, able to anticipate every need before it arose, I saw myself rising through the ranks and becoming indispensable to a high-powered corporate executive. I wanted freedom and excitement; that’s what I said. And that was partly true, but it wasn’t the whole story.

I had just enough ability to make my hubris seem like healthy ambition. Even after the Crash hit, I’d always landed on my feet in Boston; even been able to take my pick of jobs. I thought I could make it. And for a short time, I suppose I did. I got a job at a brokerage firm working for the CEO and bought myself a fancy new hat to celebrate. But after six months the business went bankrupt and they found him underneath his desk, burning pages from his address book. After that I received an extended lesson in humility.

Turns out I wasn’t as uniquely talented as I thought, that the city was crammed to the gills with girls with the same credentials, and the landlady at the Nightingale wasn’t very patient when it came to rent. I ended up working as a taxi dancer at the place on Broadway, the Orpheum. They were short on redheads and prided themselves on catering to all tastes. So I got a job dancing with strangers.

I went from top of my typing class to bottom of the pecking order in the girls’ locker room. I rented a secondhand gown from one of the other dancers and borrowed a pair of slippers until I got paid. The other girls weren’t particularly nice or mean, just jaded and tired. And luckily for me, there wasn’t that much competition in the redhead section. You have to sit in groups round the edge of the dance floor, blondes with blondes, brunettes with brunettes, and the guys stroll around eyeing you up the way a woman looks at an apple at a fruit stall—trying to find one that’s not too bruised, not too soft. Some girls winked and flirted, others carried on chatting among themselves as if ignoring the customers sharpened their appetite. I used to close my eyes and try to drift inside the music—I didn’t like to see the look on the guys’ faces if they passed me by.

You think you’re lucky when you’re chosen, but of course now you’ve got a whole other world of difficulty ahead of you—keeping their hands where they belonged was a full-time job, and one that had to be done with a smile on your face. And it’s not easy to make small talk with a guy who doesn’t speak any English, or who’s trying to hustle you for a free date. But every misfit in the city is your sweetheart for the next three minutes—the gropers and the bullies, the small-town Casanovas; the shy boys, the physically deformed, foreigners fresh off the boat; older men, looking for company. You have to charm them while letting them know you’re not for sale. Only you are, really.

Of course I didn’t tell Ma where I’d landed. I made up a story about being a private secretary to an eccentric millionaire—Mr. Halliday. I gave him odd habits and a demanding personality. That explained away the late nights and why I was never at the boarding house when she called. And also why I never came home.

After all, it was only meant to be temporary. But it turns out there’s a lot of money to be made as a taxi dancer—almost forty dollars a week sometimes. And I pretty much had the redhead market cornered after about a month. I found that if I had a few shots while I was getting ready and then kept myself topped up through the night, it was just about bearable. I wasn’t the only girl with a bottle in her locker—most of us had something. And it wasn’t like we went out of our way to hide it either. The management knew the score and never bothered anyone unless a girl was stupid about it and got sloppy or sick.

Pretty soon a few of us started going out after the dance hall closed, just to finish up the night. That’s when the clubs got really interesting. Sometimes I’d make it back to the boarding house and sometimes I wouldn’t. It wasn’t something I was proud of. Sleeping all day, working all night, in a city like New York gets lonely.

But then I took the watch.

Turns out that guy was really fond of that watch; his father had given it to him, and his father before that. Turns out too that he remembered where I worked and showed up the next night hell-bent on getting it back.

By that time, I didn’t even remember I’d taken it. But he found it in my coat pocket, so there was no way I could talk my way out of it. He started making a scene, right there in the middle of the dance floor, shouting that I was a thief and a liar, and then the management had no choice but to let me go.

Only that wasn’t enough for him. He figured I still owed him something. And when I came out of the back entrance of the building after cleaning out my locker, he was waiting there to get it.

You have to give it to New Yorkers—they’re pragmatic people. They don’t get involved unless they have to. They can turn a blind eye, ear, or anything else you want to name. When he was done, he left me lying in the alleyway. Somehow I managed to get up, button my coat over my torn dress, and walk twenty-three blocks back to the Nightingale.

Then I ran a bath, poured another drink, and took a razor blade with me into the bathroom.

That’s how I ended up at the Binghamton State Hospital, otherwise known as the loony bin.

BOSTON, FEBRUARY 1932 (#ulink_0aede38d-29c0-50fb-bc21-45ad1870877b)

In the end, Ma won; I found myself standing in the empty outer office of the Belmont Placement Agency in Dewey Square, wearing the gray suit. I’d lost weight; the jacket sagged around my bust like a deflated tweed balloon. I tried to cover it up with my scarf, but it was hopeless.

I wondered where everyone was. I’d known the woman who ran the agency, Maude Williams, since I began secretarial school. As a star student, I was singled out as early recruitment material, and she gave me the pick of any position I wanted. It wasn’t long ago I’d been sitting across from her, turning down extra pay because I couldn’t wait to get out of Boston. But things had changed. There was a time when Maude had a receptionist of her own; when these dingy little rooms were crammed with girls, ready to go anywhere Maude sent them. Now I was the only one there.

On the way the trolley had passed by Boylston Street, near the Common. Crowds of homeless sat huddled around campfires in a makeshift shantytown. There’d been outrage and shock over their invasion before I left, but now there were twice as many. They had become invisible in their poverty, sleeping on cardboard boxes in doorways, selling apples on street corners. It wasn’t quite as bad as New York and the sprawling Hooverville that had taken over Central Park, but still it sent a chill up my spine.

In the North End, too, there were things I hadn’t seen before—big signs hung from the front gates of the shoe factory and the railroad yard: “Jobless Men Keep Walking—We Can’t Feed Our Own.” And on Hanover Street this morning, the corner was crowded with men, maybe fifty or sixty. They were all waiting for the construction trucks to drive past on their way to the building sites in the city, looking for day workers. When they stopped, all hell broke loose—swarms of bodies engulfed them, shouting, shoving, clambering aboard. The foreman had to push them down like animals, banging on the side of the truck to start moving again.

Please God that didn’t happen to me.

I jammed my hands into my pockets.

“Ouch!” Something sharp stabbed my palm, and I pulled out a bent safety pin. Another one of Ma’s superstitions: “A crooked pin in the pocket brings good luck.”

A minute later I was sitting across from Maude—short and solid, somewhere in her late fifties, a hard smear of red lipstick highlighting her thin lips and thick black glasses framing her eyes. Straight-talking and unflappable, Maude was the first and often only port of call for anyone looking for a truly professional secretary. Or at least that’s the way it used to be.

“Jesus, kid!” She took a hard drag on her cigarette and leaned back in her desk chair. “I never thought I’d see you again! What are you doing back?”

“Guess I’m not cut out for the big city after all,” I said.

She nodded sagely. “Not many people are. Though I have to say, you look a bit, well, underfed. And I can’t say I like that hairstyle on you.”

“I’ll never go to that hair dresser again!” I laughed, automatically running my hand through the short curls. “It’ll grow back,” I reassured her. “Faster than you think.”

“Have you been sick or something?”

“No, no, I’m fine. Maybe I was a little homesick.”

“Perhaps you should take it easy. Rest up. Why not come see me in another week?”

It wasn’t like her to worry about anyone’s health.

“I’m right as rain. So”—I sat forward, gave her a smile full of history and complicity—“what have you got for me?”

Maude flicked a bit of ash into a mug, where it fizzled in the remains of her cold coffee. “Nothing.”

“I’m sorry?”

“I haven’t got anything for anyone, kid. Don’t you read the papers? The whole country’s out of work.”

This wasn’t the reception I’d been expecting. Maude always had some lead tucked up her sleeve.

“But, Maude”—I tried to laugh, but it came out forced, like a broken machine gun—“there has to be something!”

She picked up a single sheet in her in-tray. “See this? This is it—I’ve got one job. And about two hundred girls waiting for my phone call. And I’m sorry to say, kid, but you’re not what they’re looking for.”

“What is it?”

She squinted as she read the heading. “A temporary clerk/salesgirl.”

“But I can do that!” This time my laugh sounded real—full of relief. “I don’t care if it’s not secretarial. I’m not going to be picky!” I added graciously.

“Yes, but not just any clerk. It says”—she referred to the paper again—“‘The girl in question should be a young woman of quality, well-spoken and professional, able to create a favorable impression with affluent clientele.’” She peered at me over her glasses. “Allow me to translate: that’s ‘No Irish redheads, thanks.’ They want a blueblood. Or at least someone who passes for one. It’s one of those fancy shops on Charles Hill.”

“Look, I can’t go home with nothing, Maude. You don’t understand. I’ve got bills, debts to pay.”

“No, you’re right,” she said flatly. “I’ve never had a bill in my life.”

“What about the telephone company? They always need girls, don’t they?”

“Not anymore. They let fifty go last month.” She stubbed her cigarette out in the mug. “I’m sorry, really. I am.”

“What’s the address of this shop?”

“Oh, no!” She shook her head. “No, I’m not taking any chances! I need this commission!”

“I know how to speak properly and which fork to use at dinner!” I had an idea. “You know what? I’ll just dye my hair blond!”

“Are you kidding me? And end up looking like every two-bit secretary I already have on the books, all of them trying to be Joan Blondell or Jean Harlow? These people want a young woman of quality, not a chorus girl!”

“Please, Maude!” I was starting to sound desperate. “Just give me one chance. That’s all I’m asking.”

She winced; the conversation was painful for both of us. “I’ve known you a long time, Maeve. And you’re a smart girl with a lot of potential. But my God, if you haven’t got lousy timing!” A buzzer sounded in the room next door. “Things are tough here. Real tough. Maybe you should’ve stayed in New York.”

She got up and went into the waiting room to unlock the door.

I grabbed the paper from her in-tray. A card was attached to the bottom. I tore it off and shoved it into my pocket.

It wasn’t until I got outside in the street that I took it out again and looked at it.

WINSHAW AND KESSLER

Antiquities, Rare Objects, and Fine Art

Under the address were the following lines:

EXTRAORDINARY ITEMS BOUGHT, SOLD,

AND OBTAINED UPON REQUEST

Absolute discretion guaranteed ______

R. H. Stearns had long been established as the most exclusive department store in Boston. Located in a tall, narrow building overlooking the Common, its hallmark green awnings promised only the finest, most fashionable merchandise inside. Already the windows were dressed with pretty pastel displays of spring fashions in stark contrast to the customers, still bundled in thick winter coats and furs, browsing through the long aisles.

I didn’t go in through the polished brass doors, though, but went round to the back of the building. Normally visitors were prohibited from using the staff entrance, but I managed to walk in behind a couple of cleaning girls unnoticed. There was only one person who could help me now, and unfortunately, she wasn’t going to like it.

The alterations workshop was a large windowless room in the basement between the stock rooms and the loading bay, filled with long rows of sewing machines, ironing boards, and clothing rails. The constant clattering of the machines echoing off the cement floor and ceiling made it sound like a factory. Twenty or so women worked side by side, wearing white cotton calico smocks over their street clothes. The department was presided over by Mr. Vye, a very particular, exacting man in his mid-fifties who sat at a desk near the door. He assigned each garment, liaised with the customers, and oversaw the final result. Everything had to go through him, including me.

Ma had a sewing machine at the front of the room in a prime position. It was widely acknowledged that her abilities with difficult materials like silk, taffeta, organza, and brocade were extraordinary, and as a result she was the first choice for eveningwear alterations. Behind her on a dress form was a fitted gown of black velvet with rhinestone straps. When I arrived she was kneeling on the floor, pins in her mouth, taking up the hem.

Mr. Vye scowled at me, an intruder in his domain. “May I help you, young lady?”

“Oh, that’s my daughter!” Ma got up, brushed the stray threads from her knees. “You remember my daughter, Maeve, don’t you? She’s just come back from New York!”

“I’m sorry to disturb you,” I apologized. “Only I wondered if I could have a quick word with my mum.”

He nodded begrudgingly, and we went into the hall.

“I need a favor, Ma.”

“Tell me what happened at the interview. Did they have anything for you?”

“There’s not a lot out there, but there is one job. Only I need your help.” I lowered my voice. “Ma, I have to dye my hair.”

“Dye your hair?” She recoiled as if I’d just slapped her across the face. “Certainly not! You have beautiful hair! It was bad enough when you cut it. Only fast girls do that sort of thing!”

“But it’s for a job, Ma!”

“What kind of job? A cigarette girl?” She folded her arms across her chest. “Absolutely not!”

I would’ve happily taken a job as a cigarette girl, but I didn’t tell her that.

“Look, I don’t want to look fast, or cheap,” I explained. “Which is why I came to you. It’s for a job in Charles Town. An antiques shop. They want a woman of quality.”

“Really?” Now she was indignant. “And what are you, may I ask?”

I lost my patience. “What do I look like, Mum? Do you think anyone’s going to figure me for Irish? Why don’t I just go in clutching a harp and dancing a jig?”

“There’s no need to be vulgar!” But she frowned and bit her lower lip. We both knew she’d spent years erasing all traces of her Irish brogue for exactly the same reason. But dying one’s hair was vulgar and brazen as far as she was concerned. She tried to sidestep the question. “Well, I can’t help you tonight. I’m going to mass.”

“We can go to mass any night! And we haven’t got time—the interview is first thing tomorrow morning!”

But she dug in her heels. “I’m afraid I have a prior arrangement, Maeve.”

“If you help me, it will turn out all right, I know it will. I won’t look cheap or fast. But I can’t manage it on my own. Please!”

I could feel her wavering between what she thought was respectable and what she knew was necessary.

“Who knows when I’ll have another chance?” I begged.

“Maybe. If you come to church.” She drove a hard bargain, leveraging my eternal soul against the certain depravity of becoming a blonde. “But I’m warning you, Maeve, this is a terrible, terrible mistake!”

Nonetheless, she took me up to the ladies’ hair salon on the top floor and introduced me to M. Antoine. M. Antoine was French to his wealthy clients and considerably less Gallic in front of staff like Ma. Originally from Liverpool, he’d apparently acquired the accent along with most of his hairdressing skills on the boat on the way over.

He gave me the once-over from behind an entirely useless gold pince-nez. “It’s a shame, really.” He poked a finger through my red curls. “I have clients that would kill for this color!”

I avoided my mother’s eye. “Yes, but you can see how it limits me, can’t you?”

“It’s true,” he conceded, “especially in this town. Some people have no imagination.”

M. Antoine sent us home was a little bottle of peroxide wrapped in a brown paper bag, which Ma quickly jammed into her handbag as if it were bootleg gin. “No more than twenty minutes,” he instructed, firmly. “The difference between a beautiful blonde and a circus poodle is all in the timing. And remember to rinse, ladies, rinse! Rinse as if your very lives depended on it!”

The sign above the door read “Winshaw and Kessler Antiquities, Rare Objects, and Fine Art” in faded gold lettering. It swung back and forth in the wind, creaking on its chains like an old rocking chair.

I stood huddled in the doorway, waiting.

Maude’s voice rang in my head: “The girl in question should be a young woman of quality, well-spoken and professional, able to create a favorable impression with affluent clientele.”

A blueblood.

I’d looked the word up the night before. The term came from the Spanish, literally translated sangre azul, describing the visible veins of the fair-skinned aristocrats. But of course here in Boston we had our own special name for these social and cultural elite, Brahmins—old East Coast families who’d stumbled off the Mayflower to teach the English a lesson. There was an even more telling lineage behind that word; it referred to the highest of the four major castes in traditional Indian society. The Boston Brahmins were a club you couldn’t join unless you married into it, and they didn’t like to mix with anyone who’d floated in on one of the newer ships, landing on Ellis Island rather than Plymouth Rock.

Adjusting my hat in the shop-window reflection, I wondered if it would work. The effect was more dramatic than I’d expected. I looked not just different but like a whole other person; my eyes seemed wider, deeper in color, and my skin went from being white and translucent to a pale ivory beneath my soft golden-blond waves. But would it be enough?

To my mother’s credit, she’d been thorough, covering every inch of my scalp in bleach at least three times to make certain there were no telltale signs. And when it was rinsed clean, she wound it into pin curls to be tied tight under a hairnet all night. When I woke, she was already up, sitting by the stove in her dressing gown sewing a Stearn’s label into the inside lapel of my coat. “It’s one of the only labels people ever notice,” she said. “And a coat from Stearn’s is a coat to be proud of.”

“Even though it’s not from Stearn’s?” I asked.

“They won’t know that. They’ll look at the name, not the cut.”

For someone who didn’t approve of what I was doing, she was dedicated nonetheless.

Now here I was, on a street I’d never even been down before, in my counterfeit coat and curls.

It was almost nine in the morning, and no one was around. In the North End everything was open by seven; there were people to greet, gossip to share, deals to be struck. The streets hummed and buzzed morning till late into the night. But here was the stillness and order of money, of a life that wasn’t driven by hustle, sacrifice, and industry. Time was the luxury of another class.

So I practiced smiling instead—not too eager, not too wide, but a discreet, dignified smile, the kind of gentle, unhurried expression that I imagined was natural to women in this part of town, an almost imperceptible softening of the lips, just enough to indicate the pleasant expectation of having every desire fulfilled.

Eventually an older man arrived, head bent down against the wind. He was perhaps five foot five, almost as wide as he was tall, with round wire-rimmed glasses. He glanced up as he fished a set of keys from his coat pocket. “You’re the new girl? From the agency?”

“Yes. I’m Miss Fanning.”

“You’re tall.” It was an accusation.

“Yes,” I agreed, uncertainly.

“Hmm.” He unlocked the door. “I ask for a clerk, and they send me an Amazon.”

He switched on the lights, and I followed him inside. Though narrow, the shop went back a long way and was much larger than it looked from the outside.

“Stay here,” he said. “I’m going to turn on the heat.”

He headed into the back.

I’d never been in an antiques store before—the dream of everyone I knew was to own something new. And I knew all too well the used furniture stalls in the South End where things were piled on top of one another in a haphazard jumble, smelling of dust and mildew. But this couldn’t have been more different.

Crystal chandeliers hung from the ceiling, the floors were covered with oriental carpets, and paintings of every description and time period were crowded on top of one another, dado rail to ceiling, like in a Victorian drawing room. There were ornate gilded mirrors, fine porcelain, gleaming silver. I picked up what I thought was a large pink seashell, only to discover that an elaborate cameo of the Three Graces had been painstakingly etched into one side. It was the most incredible, unnecessary thing I’d ever seen. And there was a table covered with maybe thirty tiny snuffboxes or more, all decorated with intricate mosaic designs of famous monuments, like the Leaning Tower of Pisa and the Great Pyramid at Giza, none of them bigger than a silver dollar. It was more like a museum than a shop.

Little cards with neatly printed descriptions were everywhere.

Here was a “17th-century French oak buffet,” a “gilded German Rococo writing desk,” a pair of stiff-backed “Tudor English chairs” in mahogany so old they were almost black. Tall freestanding cases housed porcelain vases, pottery urns, a trio of Italian Renaissance bronzes. A row of bizarre African wooden figures squatted on the floor, staring through round cartoon eyes, comical and yet shockingly sexual at the same time. And the prices! I had to keep myself from laughing out loud. Five hundred dollars for a dresser? You could buy a brand-new automobile for less! Near the back of the shop in glass display cases trinkets, watches, and fine estate jewelry were arranged against waves of dark green velvet. The ticking of half a dozen clocks hanging from the wall, ornamented with inlaid wood and gold, sounded gently.

The place even had a smell all its own, a rich musty scent of aging wood, old textiles, and silver polish. This was the perfume of centuries and continents, of time.

Now I knew why they’d wanted a “young woman of quality.” People didn’t come here to replace a table or sofa; they were collecting, searching out the rare and unique. They wanted a girl who knew what it was like to acquire things out of amusement rather than need. Who sympathized with those whose lives were so pleasantly arranged that they hungered for beauty and meaning rather than food.

The old man returned, took off his hat. His thinning hair was weightless and fine, circling the widening bald spot on the top of his head like a white wreath. “It’ll warm up soon. I’m Karl Kessler.” He gave a tug at his suit vest, which was struggling to cover his stomach. “What was your name again?”

“May. With a y, of course,” I added. (I didn’t want to use the Irish name Maeve.) “I was named after the month of my birth,” I lied.

“And do you know anything about antiques, May with a y?”

“Oh, I know a little.” I tried to seem casual. “My family had a few good pieces. I was wondering, that buffet over there … is that oak, by any chance?”

“Why, yes. It is.”

“I thought so.” I flashed my well-practiced smile. “I’m so fond of oak, aren’t you?”

He fixed me with a sharp black eye. “Where is your family from?”

“New York. Albany, actually. But I’m here staying with my aunt.” I ran my fingers lightly along the smooth finish of a Flemish bookcase, as if I were remembering something similar back home. “You see, I had a particularly troublesome beau, Mr. Kessler. We all thought it best that I get away for a while.”

“And you can type?”

“Oh, yes! I used to type all Papa’s letters. But to be honest, I’ve never considered a sales job before.” I frowned a little, as if pondering the details for the first time. “I suppose it means working every day?”

“Yes. Yes, it does.” He nodded slowly. “But I thought the woman from the agency was sending me a girl with secretarial skills?”

“Dear old Maude!” I gave what I hoped passed as an affectionate chuckle. “You see, she’s a family friend. I told her I’d try to help her out. Though, as it happens,” I added, “I did attend the Katherine Gibbs Secretarial School. Of course, it was more of a diversion than a necessity. But if I do something, Mr. Kessler, I like to be able to do it properly. I was taught that excellence and hard work are virtues, no matter what your situation.”

“I see.”

“And the wages?” I didn’t want to seem overeager. “I suppose they’re … reasonable?”

“Twenty-five a week. Does that seem reasonable to you?”

“I’m sure it will do very nicely.”

“So”—he leaned back against the counter—“do you have other interests?”

“Oh, yes! I like to travel and read, English literature mostly. Also I do a little painting and drawing …” I tried to remember what the heroines in Jane Austen novels did. “I’m terribly fond of long walks and embroidery.”

He nodded again. “You read a great deal?”

“Absolutely. I love books.”

“So you know how to tell a story?”

“I certainly hope so, Mr. Kessler.”

“Well, selling isn’t so different from telling a story. Everything here has a history. Where it comes from, how it’s made. Why it’s important. Once you understand that, the rest is easy. For example, take this piece.” He walked over to a small writing desk. “This is an eighteenth-century German Rococo Toilletentisch. This little table had many uses in its day. Primarily it would have been a dressing table, which is why it has a mirror in the center. Inside, below the mirror, the wash utensils would be stored.” He opened up the small drawers. “And to the sides, jars, combs, and jewelry. But that’s not all. There’s space for writing and working, playing card games. These tables are light enough to be easily carried from room to room. Mechanical fittings enable them to change use, for example from tea table to games table. It’s a fine example from the workshop of Abraham and David Roentgen, specialists in constructing such furniture.”

“Why, it’s ingenious!”

“Isn’t it?” he agreed. “But that’s not why someone would buy it. Someone would choose this little table over all the other little tables on this street for one reason alone: because it belonged to Maria Anna Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s older sister. Because this little table, with all its uses, sat in the same room, day after day, with the world’s greatest composer as he learned his scales as a boy.” His hand rested tenderly on the delicate inlaid wood top. “She wrote in her diary here, the same diary that her brother would later steal and fill with false entries about himself, all in the third person.”

“Really?” Suddenly I pictured it in a room with a harpsichord and a violin, overlooking the cobblestone streets of Salzburg, snowflakes dancing in the icy winter air. “How do you know all that?”

Mr. Kessler gave a little shrug. “You doubt me? I believe it because that’s what I’m told. Just as I believe you’re from Albany and used to type all your father’s letters.”

My heart skipped a beat, and I felt the heat rising in my cheeks. “Why … I’m not sure what you mean …”

He raised a hand to stop me. “A good counterfeit is as much a work of art as the real thing. Perhaps even better, May with a y. You see, I spoke to the lady at the agency yesterday afternoon. She rang to say she had a nice, reliable girl for me named Roberta, but she needed my address again because someone had stolen my card.”

I opened my mouth but nothing came out. I’d pushed it too far.

“And that, Miss Fanning, is how you sell an antique table. With a story and a smile and a healthy dose of truth and lies.” He cocked his head to one side. “The woman from the agency also told me to be on the lookout for a very determined redhead. I’m beginning to wonder, is your hair really blond?”

“Well, it is now!” I headed to the door.

“Where are you going?” he called.

I whipped round. “I beg your pardon?”

“You’re angry!” Mr. Kessler chuckled. “Well, that beats all!”

“You think I’m funny?” Embarrassment vanished; now I was furious. “There’s nothing funny about it, Mr. Kessler! I’m flat broke, and I need a job!”

“And I still need a clerk. In fact”—he ran his fingers through his beard—“a blonde from Albany would suit me very well.”

“Ha, bloody, ha!” I flung open the door.

“Hold on a moment! I need a girl who can make sales and keep the books, and who fits in with my customers.”

“What about Roberta?”

He gave a distinctly Eastern European shrug, a kind of slow roll of the shoulders that came from centuries of inherited resignation. “I doubt Roberta has your dramatic intuition. Now calm down and close the door. Let’s see your dress.”

“Why?”

“Come now!” He made a soft tutting noise, as if he was luring a stray cat with a saucer of milk. “No one’s going to hurt you.”

I closed the door and took off my coat, careful to hold it so the label showed. I was wearing the navy blue knit. It was the nicest outfit I owned, and even at that, I’d spent the night before darning moth holes beneath the arms.

Mr. Kessler opened up the jewelry cabinet and took out a long string of pearls and a pair of pearl clip-on earrings. “Here,” he said, handing them over. “You can wear what you like from the display, as long as it goes back at the end of the day. If a man comes in, he likes to see the jewelry on a pretty girl. It’s the easiest way to sell it.”

I wasn’t sure I understood. “Are you hiring me?”

“If you can keep the fiction for the customers, you might be rather useful. I’m looking for someone adaptable, with a pragmatic disposition. And I have to admit, your stories have flair.” He winked, tapping the side of his nose. “The bit about the persistent beau was clever. You’ll be good at selling.”

“But … but aren’t you afraid I’m going to steal something?”

He gave me a rather surprised look. “Are you?”

“Well, no.”

“You’re an actress, May with a y. Not a thief,” he informed me. “A real thief doesn’t warn you of their intentions.”

I followed him back behind the glass counters to a room divided into two offices. He hung his coat up in one and pointed to the other. “You can use that desk. It’s Mr. Winshaw’s.”

“Won’t Mr. Winshaw need it?”

“Mr. Winshaw isn’t here. Do you drink tea or coffee?”

“Coffee, please.”

“So do I.” He gestured to the back storage room. “There’s a sink in the bathroom and a kettle on the hot plate.”

Then he went inside his office and closed the door.

I stood there, unsure of what exactly had just happened.

Then I slipped the pearls over my head. There was no mistaking the real thing. They were heavy with a creamy golden-pink luster. The echo of some long-lost perfume clung to them; sensual, sharp, and sophisticated, it could be muted by time but not silenced.

Instantly they transformed that old blue knit; when your jewels are real, your dress doesn’t matter.

But no sooner had I put them on than an eerie feeling came over me, at once familiar yet anxious and uncertain.

The pearls reminded me of someone—the girl on the far ward.

BINGHAMTON STATE HOSPITAL, NEW YORK, 1931 (#ulink_c55eeed0-ea26-5621-a851-8c4a4397f4e4)

She was wearing pearls. That was the first thing I noticed about her. Large and even, perfectly matched, falling just below her collarbone over the thin blue cotton hospital gown. She strolled into the day room of the Binghamton State Hospital with its bare, institutional green walls and floor stinking of strong bleach like she was wandering into the dining room of the Ritz. Willowy and fine boned, she had blue eyes fringed by long, very black lashes and deep brown hair cut in a straight bob, pushed back from her face. A navy cardigan was draped casually over her shoulders, as if she were on her way to a summer luncheon and had turned back at the last minute to grab it, just in case the weather turned.

The rest of us were in the middle of what the nurses referred to as “occupational therapy,” or making ugly hook rugs. The girl with the pearls moved slowly from table to table like visiting royalty, surveying everyone’s work with a benign, interested expression.

“Oh, how interesting!” she’d murmur, or “What an unusual color choice!”

Then she stopped beside me. Up went a perfectly plucked eyebrow, like a question mark. “Well, now! Surely that’s the most deeply disturbing thing I’ve ever seen in my life!”

“Well, no one’s asking you, are they?” I was tired of crazy people. And this place was bursting with them in all shapes and sizes.

“There’s no need to take it that way. It’s a very powerful piece.”

I glared at her. “It’s not a piece. It’s a rug.”

“A very angry rug, if you ask me.” She sat down, picked up a hook. “Go on then—show me how you do it.”

I wasn’t in the mood for a demonstration. I was only here because the staff made me come, hauling me out of my usual spot in the rocking chair by the window. “Ask the nurse if you’re so interested.”

She laughed. It was a drawing-room laugh—the practiced jocularity of a hostess, high and false. “Don’t be so serious—I’m only teasing you!” She nodded to the other women in the room. “You’re the best of the lot, you know. An artist!”

It wasn’t much of a compliment. There were maybe a dozen of us rounded up for the afternoon session, all dressed in shapeless blue smocks, heads bowed over our work. There’d been a lice outbreak, and we’d all been clipped. But this girl still had a good head of hair. She must be new. The two of us were the youngest in the room by maybe ten years, although it was hard to tell for sure.

“So you’re a connoisseur, is that it?” I pointed to a thin, wiry woman in her mid-fifties with no teeth, furiously hooking across the room. “Mary’s pretty good. Why don’t you go bother her? She doesn’t speak. Ever. But she can make a rug in an afternoon.”

The girl twirled the hook between her fingers. “But you have talent—a real feeling for the medium, possibly even a great future in hooked rugs. Provided of course that people don’t want to actually use them in their homes. So”—she leaned forward—“tell me, how long have you been here?”

I yanked another yarn through. I’d been here long enough to wonder if I’d ever be allowed out again. Mine was an open-ended sentence: I needed the doctor’s consent before I’d see the outside world again. But I wasn’t about to let her see that I’d never been so alone and terrified in my life. I gave a shrug. “Maybe a month, I don’t know,” as if I hadn’t been counting every hour of every day. “What about you?”

“I’m just stopping in for a short while,” she said vaguely.

“‘Stopping in’?” I snorted. “On your way where, exactly?”

She ignored my sarcasm. “Why are you here? In for anything interesting?”

“This isn’t a resort, you know,” I reminded her.

“Are you here voluntarily or as a ward of the county?”

I gave her a look.

“You never know”—she held up her hands apologetically—“some people come in on their own.”

“Did you?”

For someone who liked asking questions, she was less keen on giving answers. Crossing her legs, she jogged her ankle up and down impatiently. “They say it’s an illness. Do you believe that? That we can all be magically cured?”

“How would I know? Where did you get those pearls?”

“My father gave them to me.” She ran her fingers over them in an automatic gesture, as if reassuring herself over and over again that they were still there. “I never take them off.”

“Neither would I.”

“I like them better than diamonds, don’t you? Diamonds lack subtlety. They’re so … common.”

She was definitely crazy. “Not in my neighborhood!” I laughed.

“Well …” Her fingers ran over the necklace again and again. “He’s dead now.”

“Who?”

“My dear devoted father.”

I considered saying something sympathetic, but social niceties weren’t expected or appreciated much here. Besides, I didn’t want her to feel like she could confide in me.

The girl watched Mute Mary across the room, working away. “What are you really in for?”

“What’s it to you?”

“Come on! Your secret’s safe—who am I going to tell?”

I don’t know why I told her, maybe just so she’d shut up and go away, or maybe in some sick way I was trying to impress her. “I cut myself with a razor blade.”

She didn’t miss a beat. “Deliberate or accidental?”

“Deliberate.” It was the first time I’d ever admitted it aloud.

But if I expected a reaction, I was disappointed; she didn’t bat an eye.

“So no voices in your head or anything?”

“No. What about you?” I looked across at her. “Do you hear voices?”

“Only my own. Mind you, that’s bad enough. I’m not entirely sure I’m on my side.”