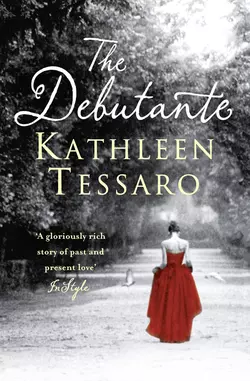

The Debutante

Kathleen Tessaro

Can the secrets of one woman’s past change another woman’s future?Endsleigh House stands, crumbling and gracious, on the south-west coast of England, its rooms shut up and dusty. But what secrets do they hold?Cate, an exile from New York, is sent to help value the contents of the once-grand Georgian house. Cataloguing its' contents with Jack - a man with his own dark past, she comes across a hidden shoebox containing an exquisite pair of dancing shoes from the 1930s, along with a mysterious collection of objects: a photograph, a dance card and a Tiffany bracelet.Returning to London, rather than face the questions lingering in her own life, Cate immerses herself in piecing together the clues contained in the box to uncover a story, that of Irene Blythe and her sister Diana - two of the most famous debutantes of their generation.The tale that unfolds is one of dark, addictive love, and leads Cate to face up to secrets of her own. Can the secrets of Baby Blythe's past change Cate's own ability to live and love again?

The

Debutante

Kathleen Tessaro

Copyright (#ulink_949b8ddd-82fc-504c-98b0-6c9b7aec8dea)

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2010

Copyright © Kathleen Tessaro 2010

Kathleen Tessaro asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007215393

Ebook Edition © APRIL 2010 ISBN: 9780007366019

Version: 2016-10-26

For Annabel

There is a dangerous silence in that hour A stillness, which leaves room for the full soul To open all itself, without the power Of calling wholly back its self-control: The silver light which, hallowing tree and tower, Sheds beauty and deep softness o’er the whole, Breathes also to the heart, and o’er it throws A loving languor, which is not repose.

LORD BYRON, Don Juan

Contents

Cover Page (#u76408018-5f10-5157-9be9-fbb391a62654)

Title Page (#u58863893-ff84-5f87-bf54-75a31f09fc68)

Copyright (#u4b0f317a-a597-5406-8884-f4afe4858698)

Dedication (#u1d210aed-79d4-54a6-97e7-85f2e9702dbe)

Epigraph (#u671de5cb-bb25-59c6-9882-22c0a1a2ddf0)

Part One (#uaca4e041-a281-5cc4-9c05-66d75573c002)

In the heart of the City of London (#u98a76664-91b1-5107-9bab-ad3c43ef7a8c)

Part Two (#litres_trial_promo)

5 St James’s Square (#litres_trial_promo)

5 St James’s Square (continue) (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Endsleigh Devon (#litres_trial_promo)

Read an extract of The Perfume Collector by Kathleen Tessaro (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading – The Perfume Collector (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading – Rare Objects (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Kathleen Tessaro (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Part One (#ulink_42c920a8-e4fa-598e-8459-16feefd2cb91)

In the heart of the City of London (#ulink_0d84571f-443a-5686-92a5-6523bc370072), tucked into one of the winding streets behind Gray’s Inn Square and Holborn Station, there’s a narrow passage known as Jockey’s Fields. It’s a meandering, uneven thread of a street that’s been there, largely unchanged, since the Great Fire. Regency carriages gave way to Victorian hackney cabs and now courier bikes speed down its sloping, cobbled way, diving between pedestrians.

It was early May; unseasonably hot – only nine in the morning and already seventy-six degrees. A cloudless blue sky set off the white dome of St Paul’s Cathedral in the distance. The pavement swelled with armies of workers, streaming from the nearby Tube station; girls in sorbet-coloured summer dresses, men in shirtsleeves, jackets over their arms, carrying strong coffee and newspapers, the rhythm of their heels a constant tattoo on the pavement.

Number 13 Jockey’s Fields was a lopsided, double-fronted Georgian building, painted black many years previously, and in need of a fresh coat, sandwiched between a betting office and a law practice. The door of Deveraux and Diplock, Valuers and Auctioneers of Quality, was propped open by a Chinese ebony figure of a small pug dog, most likely eighteenth century but in very bad repair, in the hopes of encouraging a gust of fresh morning air into the premises. Golden shafts of sunlight filtered in through the leaded glass windows, dust floating, suspended in its beams, settling in thick layers on the once illustrious, now slightly shabby interior of one of London’s lesser known auction houses. The oriental carpet, a fine specimen of the silk hand-knotted variety of Northern Pakistan during the last century, was threadbare. The delft china planters which graced the mantelpiece, brimming with richly scented white hyacinth, were just that bit too chipped to be sold at any real profit; and the seats of the 1930s leather club chairs by the fireplace sagged almost to the floor, their springs poking through the horse-hair backing. Reproduction Canalettos hung next to the

better watercolour dabblings of long-dead country-house hostesses; studies of landscapes, flowers and fond attempts at children’s portraits. For Deveraux and Diplock was the natural choice of those once aristocratic families whose fortunes had lost pace with their breeding and who wished to have their heirlooms sold quickly and discreetly, rather than in the very public catalogues of Sotheby’s and Christie’s. They were known by word of mouth and reputation, having traded with the same European and American antique dealers for decades. Theirs was a dying art for a dying class; a kind of undertakers for antiquities, presided over by Rachel Deveraux, whose late husband Paul had inherited the business when they were first married thirty-six years ago.

Rachel, smoking a cigarette in a long, mother-of-pearl holder which she’d acquired clearing the estate of an impoverished 1920s film star, sat contemplating the mountain of paperwork on her huge, roll-top desk. At sixty-seven, she was still striking, with large brown eyes and a knowing, disarming smile. Her style was unorthodox; flowing layers of modern, asymmetrical Japanese-inspired tailoring. And she had a weakness for red shoes that had become a personal trademark over the years – today’s pair were vintage Ferragamo pumps circa 1989. Pushing her thick silver hair away from her face, she looked up at the tall, well-dressed man prowling the floor in front of her.

‘It will be fun, Jack.’ She exhaled; a long, thin stream of smoke rising like a spectre, floating round her head.

‘Think of her as a companion, someone to talk to.’

‘I don’t need help. I’m perfectly capable of doing it on my own.’

Jack Coates gave the impression of youth even though he was nearing his mid-forties. Slender, with elegant aquiline features, thick lashes framing indigo eyes, he moved with an animal grace. His dark hair was closely cropped, his linen suit well-tailored and pressed; yet underneath his polished exterior a raw, unpredictable energy flowed. He was a man straining at his own definition of himself. Frowning, he stopped, fingers drumming the top of the filing cabinet.

‘I prefer to do it alone. There’s nothing more tedious than talking to strangers.’

‘It’s a three-hour drive.’ Rachel leaned back, watching him. ‘She’ll hardly be a stranger by the time you arrive.’

‘I’d rather go on my own,’ he said, again.

‘That’s the trouble with you; you rather do everything on your own. It’s not good for you. Besides –’ she flicked a bit of ash into an empty teacup – ‘she’s very pretty.’

He looked up.

She arched an eyebrow, the hint of a smile on her lips.

‘What difference does that make?’ Jamming his hands into pockets, he turned away. ‘Perhaps I should point out that this isn’t some small turn-of-the-century Russian village and you’re not an ageing Jewish matchmaker eking a living out by tossing complete strangers together and adding a ring. We’re in London, Rachel. The millennium dawns. And I’m perfectly capable of doing the job I’ve been doing for the past four years on my own – without the assistance of young nieces of yours, fresh from New York, trailing round after me.’

She tried a different tack.

‘She’s an artist. She’ll be very helpful. She has an excellent eye.’

He snorted.

‘She’s had a difficult time of it lately.’

‘Which what, roughly translates to “she’s broken up with her boyfriend”? Like I said, I don’t need a companion. And especially not some moody art student who’ll spend the entire time on the phone, arguing with her lover.’

Stubbing out her cigarette, Rachel took out her reading glasses. ‘I’ve already told her she can go.’

He swung round. ‘Rachel!’

‘It’s a large house, Jack. Even with two of you, it will take you days to value and catalogue the whole thing. And whether you deign to acknowledge it or not, you need help. You don’t have to talk to her at length or share the contents of your innermost heart. But if you can manage to be civil, you might just notice that it’s actually nicer not doing everything on your own.’

He paced like a caged animal. ‘I can’t believe you’ve done this!’

‘Done what?’ She looked at him hard over the top of her glasses. ‘Hired an assistant? I am your employer. Besides, she’s smart. She studied at the Courtauld, Chelsea, Camberwell –’

‘How many art colleges does a person need?’

‘Well,’ she grinned slyly, ‘she was very good at getting

into them.’

‘This isn’t helping.’

She laughed. ‘It will be an adventure!’

‘I don’t want an adventure.’

‘She’s different now.’

‘I work alone.’

‘Well –’ she rifled through the stacks of invoices and receipts, searching for something – ‘now you have an assistant to help you.’

‘This is nepotism, pure and simple!’

She looked up. ‘Nothing about Katie is pure or simple. The sooner you understand that, the easier it will be.’

‘What did she do in New York anyway?’

‘I’m not sure.’

‘I thought you two were close.’

‘Her father had just died. He was young; an alcoholic. She wanted a new start and we had some connections there; Paul knew one or two dealers who might be willing to help her find her feet. Tim Bolles, Derek Constantine –’

‘Constantine?’ Jack stopped. ‘I thought he only catered for the super-rich.’

‘Yes, well. He took a shine to her.’

‘I’ll bet he did!’

She gave him a look. ‘I don’t believe he’s that way inclined.’

‘I’m sure he inclines himself to whoever’s got the cash, which doesn’t exactly add to his charms.’

‘New York is not a city a young woman can just waltz into. You need contacts.’ Opening the top drawer, she sifted through its contents. ‘I’m just guessing, but I take it you don’t like him.’

‘My father had dealings with him. Years ago. So –’ he changed the subject – ‘she’s staying with you, is she?’

‘For the time being. Her mother lives in Spain.’ She sighed; her face tensed. ‘She’s so different. So entirely, completely different. I’d heard nothing for months…not even a phone call…and then out of blue, there she was.’

Suddenly a courier bike, buzzing like a giant wasp, tore past the doorway at breakneck speed.

‘Good God!’ Jack turned, tracking it as it narrowly avoided a couple of girls, coming out of a coffee shop. ‘They’re a menace! One of these days someone’s going to get hurt!’

‘Jack.’ Rachel pressed her hand over his and gave him her most winning smile. ‘Do this for me, please? I think it will be good for her; a trip to the country, time with someone closer to her own age.’

‘Ha!’ He squeezed her fingers lightly before moving his hand away. ‘I’m not a babysitter, Rachel. Where is this house anyway?’

‘On the coast in Devon. Endsleigh. Have you ever heard of it?’

He shook his head. ‘Look, I’m not…you know, good with people.’

‘Maybe. But you’re a good man.’

‘I’m an awkward man,’ he corrected, wandering over to the fireplace.

‘You don’t need to worry. Katie won’t be a problem, I promise. You might even enjoy it.’ She caught his eye in the mirror hanging above the mantelpiece. Her voice softened. ‘You need to make an effort now.’

‘Yeah, that’s what they tell me.’

Rachel was quiet. A rare breeze rustled the papers in front of her.

‘Well. There we go,’ Jack concluded. He picked up his briefcase from where he’d left it, on the seat of one of the sagging leather chairs, and headed for the door. ‘I’ve got work to do.’

‘Jack…’

‘Tell your niece we leave at eight thirty tomorrow.’ He turned. ‘And I’m not wasting the whole morning waiting for her, so she’d better be ready. Oh –’ he paused on the threshold – ‘and we’ll be listening to Le Nozze di Figaro on the way down, so no conversation necessary.’

She laughed. ‘And if she doesn’t like opera?’

‘She doesn’t need to come!’ He waved, striding out, quickly lost in the stream of people on Jockey’s Fields.

Rachel pulled off her glasses, rubbed her eyes. They hurt today; not enough sleep.

Digging through her handbag, she pulled out her cigarettes.

This job wasn’t good for him. He needed to be somewhere he could be around people, back in the thick of life, not picking through the belongings of the dead. Perhaps she ought to hire a secretary. Some cheerful young woman to bring him out of himself. A redhead, perhaps?

Catching herself, she smiled. He was right; she wasn’t a Jewish matchmaker.

Swivelling round in her chair, she flicked through the piles of paper, looking again for the phone number. Her late husband always claimed her very distinctive filing system would fail her one day. Today was not the day though; she needed more than anything to talk to her sister Anna. Especially now that Katie was back. The role of matriarch was Anna’s forte. Rachel did Bohemia, Anna domesticity. That was the way it had always been. At least that was the way it had been until Anna’s recent decampment to a small town outside Malaga left Rachel feeling unexpectedly abandoned and strangely affronted. Her shock was purely selfish, she knew that. Her sister had dared to change the well-worn script of their roles without consulting her, tossing off her old life as if it were nothing more than a garment, grown shapeless and illfitting from too much use.

‘I’m tired of London,’ Anna had declared, as Rachel helped her pack up the flat she’d owned in Highgate for twenty-two years. ‘I want to start again, somewhere fresh, where nobody knows me.’

She’d had a child’s optimism that day; a purpose and energy Rachel hadn’t seen in her for years. And secretly she’d envied her courage and the audacity of her sureness. Anna’s life hadn’t been easy. The childhood sweetheart she’d married failed her, turning into a desperate, unreliable alcoholic. She’d struggled to raise Katie on her own, only to endure her silences and rebellion, followed by her sudden desertion to America. It was no wonder Anna decided to escape. And she deserved a new life in a country bathed in sun and warm Latin temperament. Still, when she’d rung last week, Rachel had been short with her; fractious. She’d scribbled her number down on some scrap, promising herself she’d transfer it to her address book later. Now it was later and she couldn’t find the damn thing.

Hold on. What was this?

She tugged at the corner of something jutting out beneath a pile of overdue VAT forms.

It was a postcard.

At first glance it appeared to be of Ingres’s famous painting Odalisque. But on closer examination the blue eyes of the reclining courtesan were painted pale green, the same clear celadon as Katie’s. One half of her face was bathed in shadow, the other in light. Her unnerving gaze managed nevertheless to be elusive; her very directness a mask behind which she remained hidden. Turning it over, there was a message scrawled across the back in Katie’s near-hieroglyphic hand.

‘Portrait of the artist’ xxK

Across the bottom it read, ‘The Real Fake: Original Reproductions by Cate Albion’.

Cate. She’d changed everything she could about herself

– her name, her hair colour, even her work. Reproductions of old masters were a far cry from the huge triptychs she produced in art school; full of rage and surprising power. But then again, part of her talent was always her ability to reinvent herself, ransacking wide-ranging styles and iconography with a ruthlessness and speed that was frightening.

Nothing was pure and simple about Katie. Even her career was layered with illusion and double entendre.

It wasn’t what she was looking for, yet Rachel slipped it thoughtfully into the large leather handbag at her feet.

The real fake.

As a child Katie was shy, introverted; looked like she was made of glass. But if there was something broken, something missing, she was invariably behind it. Or, later on, if there was a party when someone’s parents were out of town, it would turn out to have been Katie’s idea. The girl caught not only smoking behind the bicycle sheds at school, but selling the cigarettes too? Katie. There was fire, a certain streak of will that burned slowly, deeply, beneath the surface; flaring when challenged. It was surprising, perverse; often funny and ironic.

Rachel thought again of the lost young woman, wandering around her flat in Marylebone. So quiet, so unsure.

When she’d asked Katie what had brought her back to London, she’d simply shrugged her shoulders. ‘I need a break. Some perspective.’ Then she’d turned to Rachel, suddenly wide-eyed, tense. ‘You don’t mind, do you?’

‘No, no of course not.’ Rachel had assured her. ‘You must stay as long as you like.’

She’d dropped the subject after that. But the expression on Katie’s face haunted her.

Lighting another cigarette, Rachel cradled her chin in her hand, taking a deep drag.

It wasn’t like Katie to be frightened.

Secretive, yes. But never afraid.

Jack drove up in front of number 1a Upper Wimpole Street the next morning in his pride and joy, an old Triumph, circa 1963. There on the doorstep was a young woman, slight, slender; hair in a sleek bob, white blonde in the early-morning sun. Her face was oval, with green eyes; her skin a light golden tan. She was wearing a pale linen dress, sandals and a cream cashmere cardigan. In one hand she had an overnight case and in the other a vintage Hermès Kelly bag in bright orange. Silver bangles dangled from her delicate wrists, a simple, slightly pink strand of pearls round her neck.

She was beautiful.

It was disturbing how attractive she was.

This was not the struggling artist he was expecting. This was a socialite; a starlet; a creature of style, grace and poise. Walking down the steps, she moved with a slow undercurrent of sexual possibility. When she slid into the seat next to him, Jack was aware of the soft scent of freshcut grass, mint and a hint of tuberose; a heady mix full of sharp edges and refined luxury. It had been a long time since an attractive woman had sat next to him in his car. It was an unsettling, sensuous feeling.

Turning, she extended her hand. ‘I’m Cate.’

Her palm slipped into his; cool and smooth. He found himself not shaking it, but instead holding it, almost reverently, in his own. She smiled, lips parting slowly across a row of even white teeth, green eyes fixed on his. And before he knew it, he was smiling back, that slightly lopsided grin of his that creased his eyes and wrinkled his nose, at this golden creature whose hand fitted so nicely into the hollow of his own; who adorned so perfectly the front seat of his vintage convertible.

‘You don’t want to do this and neither do I.’ Her voice was low, intimate. ‘We needn’t make conversation.’

And with that, she withdrew her hand, knotting a silk scarf round her head; slipping on a pair of tortoiseshell sunglasses.

And she was gone, removed from him already.

He blinked. ‘Do you like…is opera all right? Le Nozze di Figaro?’

She nodded.

He pressed the play button, started the engine and pulled out into traffic. He’d been dreading the social strain of today so much that sleep was an impossibility. Earlier, while packing his bag, he’d cursed Rachel.

Now, as he drove into the wide avenue of Portland Place, the cool green of Regent’s Park spread before them, he was baffled, bemused. He’d anticipated a nervous self-absorbed girl; someone whose inane questions would have to be fended off. It was his intention to create an unspoken boundary between them with the briskness of his tone and the curtness of his replies. But now his mind raced, trying to devise some clever way of hearing the sound of her voice again.

Of course, he could always ask a simple question. But there was something delicious about sitting next to her in silence. Their intimacy was, after all, inevitable; hours, even days, stretched before them. He sensed that she knew this. And it intrigued him.

Keenly conscious of every movement of his body next to hers, he downshifted, his hand almost brushing against her knee. The furious zeal of the overture of Le Nozze di Figaro filled the air around them with exquisite, frenetic intensity. They sped round the arc of the Outer Circle of the park. The engine roared as he accelerated, ducking around a long line of traffic in an uncharacteristically daredevil move.

And suddenly she was laughing, head back, clutching her seat; an unexpectedly low, earthy chuckle.

She’s a woman who likes speed, he thought, childishly delighted with the success of his manoeuvre. And before he knew it, he was overtaking another three cars, zipping through a yellow light on the Marylebone Road and cutting off a lorry as they merged onto the motorway.

Horns blared behind them as they raced out of London.

And, for the first time in a long while, all was right with the world. It was a beautiful, sun-drenched morning – the entire summer spread out before them. He felt handsome, masculine and young.

And he was laughing too.

High on a cliff where the rolling countryside, dotted with cows and lambs, met the expanse of sea, Endsleigh stood alone. Part of an extensive farm, it commanded a view over the bay beneath and the surrounding hills that was breathtaking. Built in pale grey stone by a young, ambitious Robert Adam, it rose like a miniature Roman temple; its classical proportions blending harmoniously into the rich green fields that surrounded it, mirroring the Arcadian perfection of the landscape with its Palladian dome and restrained, slender columns. High stone walls extended for acres on either side of the house, protecting both the formal Italian rose gardens and the vegetable patches from the stormy winter winds, while the arched gravel drive and the central fountain, long out of use, lent the house an air of refined, easy symmetry.

It was impressive yet at the same time unruly, showing signs of recent neglect. The front lawns were overgrown; the fountain sprouted dry tufts of field grass, high enough almost to blot out the central figure of Artemis with her bow and arrow, balanced gracefully on one toe, midchase. There was no one to care if the guttering sagged or the roses grew wild. It was a house without a guardian; its beautiful exterior yielding, slowly, to the inevitable anarchy of nature and time.

Just before the drive, a discreet sign pointed the way to a campsite on the grounds, nearly a mile down the hill, closer to the shore and out of sight of the occupants in the main house. Below, the bay curved gently like an embracing arm, and beyond, the ocean melted into the sky, a pale grey strip blending into a vast canopy of blue. It was cloudless, bright. Cool gusts tempered the heat of the midday sun.

Jack pulled up, wheels crunching on the gravel of the drive, and turned off the engine.

They sat a moment, taking in the house, its position; the view of the countryside and the sea beyond. Neither of them wanted to move. Silence, thick and heavy, pressed in around them, tangible, like the heat. It was disorientating. The internal compass of every city dweller – the constant noise of distant lives humming away in the background – was missing.

‘It’s much bigger than I thought it would be,’ Cate said at last.

It was an odd observation. The beauty of the place was obvious, overwhelming. Could it be that she was calculating how long they would be alone here?

‘Yes. I suppose it is.’

Swinging the car door open, she climbed out. After so much time driving, the ground felt unsteady beneath her feet.

Jack followed and together they walked past the line of rose bushes, full-blown and fragrant, alive with the buzzing of insects, to the front door.

He pressed the bell. After a moment, footsteps drew closer.

A tall, thin man in a dark suit opened the heavy oak door. He was in his late fifties, with a long, sallow face and thinning, grey hair. He had large, mournful eyes, heavily ringed with dark circles.

‘You must be Mr Coates, from Deveraux and Diplock,’ he surmised, unsmiling.

‘Yes.’

‘Welcome.’ He shook Jack’s hand.

‘And this is Miss Albion, my…assistant,’ Jack added.

‘John Syms.’ The man introduced himself, inclining his head slightly in Cate’s direction, as if he’d only budgeted for one handshake and wasn’t going to be duped into another. ‘From the firm of Smith, Boothroy and Earl. We’re handling the liquidation of assets on behalf of the family.’ He stepped back, and they crossed the threshold into the entrance hall. ‘Welcome to Endsleigh.’

The hall was sparse and formal with black-and-white marble tiles and two enormous mahogany cabinets with fine inlay, both filled with collections of china. Over the fireplace hung a large, unremarkable oil painting of the house and grounds. Four great doors led off the hall into different quarters.

‘How was your journey?’ Mr Syms asked crisply.

‘Fine, thank you.’ Cate turned, examining the delicate Dresden china figurines arranged together in one of the cabinets. Their heads were leaning coyly towards one another, all translucent porcelain faces and pouting pink rosebud mouths, poised in picturesque tableaux of seduction and assignation.

‘Yes, traffic wasn’t too bad,’ Jack said, immediately wishing he’d thought of something less banal.

Mr Syms was a man of few words and even fewer social graces. ‘Splendid.’ Pleasantries dispensed with, he opened one of the doors. ‘Allow me to show you around.’

They followed him into the main hall with its sweeping galleried staircase, lined with family portraits and landscapes. It was a collection of country-house clichés – a pair of stiff black Gothic chairs stood on either side of an equally ancient oak table, stag’s heads and stuffed fish were mounted above the doorways; tucked under the stairwell there was even a bronze dinner gong.

Cate looked up. Above, in a spectacular dome, faded gods and goddesses romped in a slightly peeling blue sky. ‘Oh, how lovely!’

‘Yes. But in rather bad repair, like so much of the house. There are ten bedrooms.’ Mr Syms indicated the upper floors with a brisk wave of his hand. ‘I’ve had the master bedroom and Her Ladyship’s suite made up for you.’

He marched on into the dining room, an echoing, conventional affair with a long dining table tucked into the bay-fronted window overlooking the fountain and front lawns. ‘The dining room,’ he announced, heading almost immediately through another door, into a drawing room with an elaborate vaulted ceiling, library bookcases, soft yellow walls and a grand piano. Marble busts adorned the plinths between shelves; two ancient Knole settees piled with cushions offered a comfortable refuge to curl up with a book and a cup of tea. A ginger cat basked contentedly in a square of sun on top of an ottoman, purring loudly.

‘The drawing room.’

He swung another door open wide.

‘The sitting room.’

And so the tour continued, at breakneck speed; through to the morning room, the study, gun room, the flshing-tackle room, the pantry, the silver room, the main kitchen with its long pine table and cool flagstone floors leading into the second, smaller kitchen and cellars. It was a winding maze of a house. No amount of cleaning could remove the faint smell of dust and damp, embedded into the soft furnishings from generations of use. And despite the heat, there was a permanent chill in the air, as if it were standing in an unseen shadow.

Mr Syms returned to the sitting room, unlocking the French windows. They stepped outside into a walled garden at the side of the house where a rolling lawn, bordered by well-established flower beds led to a small, Italian-style rose garden. It was arranged around a central sundial with carved stone benches in each corner. In the distance, the coastline jutted out over the bay; the water sparkling in the hazy afternoon sun.

Mr Syms guided them to the far end of the lawn where a table and chairs were set up under the cool shade of an ancient horse-chestnut tree. Tea things were laid out; a blue pottery teapot, two mugs, cheese sandwiches and a plate of Bourbon biscuits.

‘How perfect!’ Cate smiled. ‘Thank you!’

Mr Syms didn’t sit, but instead concentrated, going over some internal checklist.

‘The housekeeper, Mrs Williams, thought you might need something. Her flat is there.’ He indicated a low cottage at the back of the property. ‘She’s prepared a shepherd’s pie for tonight. And apologises if either of you are vegetarians.’ He checked his watch. ‘I’m afraid, Mr Coates, that I have another appointment and must be going. It’s my understanding that you and Miss Albion will be spending the night, possibly even two, while you value and catalogue the contents of the house. Is that correct?’

‘Yes.’

‘Here’s a set of keys and my card. If you need anything while you’re here, please don’t hesitate to contact me. Otherwise, you may leave the keys with Mrs Williams upon your departure and I anticipate hearing from you in due course regarding the value and sale of the contents.’

Jack took the keys, frowning. ‘And is everything to be sold? There are no pieces the family would like to keep?’

‘There is no family left in this country, Mr Coates. The entire estate has been purchased by developers who wish to turn it into a luxury hotel, the proceeds of which go to a number of charitable causes. So, sadly, no. Again, if I can be of any help –’

‘Forgive me, but who were they?’ Cate interrupted, settling into one of the chairs. ‘Who lived in Endsleigh?’

Mr Syms gave her a look, both surprised and slightly suspicious. ‘I thought it was common knowledge. The late Lady Avondale, more famously known by her maiden name, Irene Blythe, lived here. She died two months ago, aged ninety-two. She was a wonderful woman; very loyal and generous. Lady Avondale was an extremely active campaigner for children’s causes, especially of UNICEF. She received her OBE in 1976. Unfortunately, of course, it’s her sister everyone knows about. But that’s the way, isn’t it?’ he sighed. ‘The good in this world are never as glamorous as the bad. I’m sorry but I really must go. I’m reading a will in Ottery St Mary in an hour.’ He nodded to them. ‘It was a pleasure to meet you both. Mrs Williams is always on hand if you need anything. I hope you enjoy your stay.’ Then, with a small bow, he took his leave, cutting across the lawn with long strides.

‘Is it just me or does it feel like he’s running away?’ Cate poured out two mugs of tea. ‘Sugar?’

‘No, thank you.’ Jack picked up a sandwich. ‘He wouldn’t be the first. I have that effect on people.’

‘I’ve never heard of the Blythes.’ She passed him a mug. ‘And who is this infamous sister?’

‘Diana Blythe. The beautiful Blythe sisters. They were both debutantes; famous for being famous between the wars. Do you really not know who they are?’

Cate shook her head. ‘Am I just a mass of ignorance? Tell me everything you know.’

‘Well,’ he admitted, ‘to be honest, that’s it. I know Diana went missing during the war and was never found. Some say she went to live in America. Others think she was murdered. I’m surprised you haven’t heard of her.’

‘Obviously my education is lacking.’ Cate sipped her tea. ‘How strange and romantic!’

‘You have a very odd idea of romance.’

‘I have odd ideas about a lot of things.’ The wind blew across the lawn, gently ruffling her skirt. ‘What an old relic!’

‘The house?’

‘Hmm.’

‘You don’t think it’s charming?’

‘Well, it may be. But it’s sad too. And so staid; a great big cliché of a house.’

‘All these houses have a sameness about them. I’ve seen dozens and dozens over the years. It’s the position and the grounds that make this one special. I love looking out over the sea. And although it’s only small –’

‘Small!’

‘Ten bedrooms is nothing.’ He settled into the chair opposite. ‘I mean, it must’ve been wonderful for entertaining but it’s no size, really.’

‘Now there’s only you and me and Mrs Williams.’ Cate closed her eyes. ‘It’s peaceful,’ she sighed. ‘And the name is so evocative. Endsleigh!’

The sea was too far off to be heard but the sound of the wind through the trees, the birds and the warm smell of freshly cut grass bathed in sunlight soothed her.

‘It is peaceful,’ Jack agreed.

The dull, persistent ring of a mobile phone buzzed, coming from her handbag.

Her eyes flicked open.

It continued to ring.

‘Aren’t you going to answer it?’

‘I didn’t think there’d be a signal here.’

Finally, it stopped.

‘So,’ Jack grinned, ‘avoiding someone?’

The look on her face was cold, like being splashed by a bucket of iced water.

‘I was only –’

‘It doesn’t matter.’ She stood up. ‘It’s too hot out here.

I’m going upstairs to unpack. Let me know when you’d like to begin.’

He tried again. ‘Look, I’m sorry if I –’

‘It’s nothing,’ she cut him off. ‘It’s of no importance at all.’

Taking her handbag, she walked across the lawn. Jack watched as she stepped between the layers of sheer fabric floating in the breeze by the French windows, disappearing into the house.

17, Rue de MonceauParis

13 June 1926

My dearest Wren,

Muv sent me a copy of the article in The Times featuring your lovely photograph. Miss Irene Blythe– one of the Debutantes of the Season! And rightly so! How did they get your hair to look like that? Have you had it shingled? Remember that I want to hear every tiny detail, especially about anything that HAPPENS to you–even a brief fumble in a corridor is thrilling for me, as I am in EXILE till next year.

As for me, I am limp with boredom, despite the romance of the Greatest City in Europe. That is Madame Galliot’s constant refrain. ‘You girls are spoilt! Here you are in Paris–the Greatest City in Europe– your parents are spending a fortune on you…on and on and on…Of course she doesn’t actually allow us to go anywhere, which is too vexing. Apart from our drawing classes and trips to Ladurée (the French cannot make a decent cup of tea) and endless expeditions to churches–you can see she is truly exerting herself on behalf of my education–we are rarely allowed to venture foot into Paris itself–a theatre or nightclub, let alone two Les Folies-Bergère. She also has perfected a sneer she reserves for me when she says things like, ‘There are certain subtle refinements that simply cannot be taught,’ (cue said sneer), referring of course to the fact that you and I were not born into our class so much as thrust upon it. To her we are and always will be counterfeits. Which is why it is so thrilling to leave cuttings of The Times around for her to see!

Under her tutelage I have learned precisely three things:

* How to eat oysters.

* How to wear my hat at a beguiling angle.

* How to engage in surreptitious eye contact with men in the street, who, being French, are only too glad to ogle you back.

She has two other English girls staying with her–Anne Cartwright, who is charming, great fun and not at all above herself (she has taught me how to smoke quite successfully and without the least bit of choking) and Eleanor Ogilvy-Smith, who is a great lump of wet clay. Eleanor lives in terror of any possible form of enjoyment and every time Anne and I campaign for some tiny inch of freedom, she immediately sides with Madame Galliot and suggests another outing of the religious variety. She also spends far too much time in the bathroom. Anne and I have bets as to what she does in there–all of which would offend your propriety.

So, please! More news of the Season and every man you dance with and every single dress you wear and what you have for supper (each course) and how many marriage proposals you receive this week and if they kneel and blush and stutter with nerves, etc., when faced with your overwhelming beauty or simply faint. Also, please, please, please give me some small commission here in Paris so that I may have a legitimate reason to set forth into some of the Forbidden Zones– for example, do you need any gloves from Pigalle? Or stockings from the Lido?

I am too, too proud of you, darling! And I think Fa would be too. How am I ever to live up to my beautiful sister? J’ai malade de jalousie! (See how my French improves!)

Send my love to Muv, who must be finding the fight to keep you both chaste and marry you off at breakneck speed quite an exhilarating moral dilemma. She does, as always, write the most fantastically boring letters. They read more like housekeeping accounts than anything else. How did a woman so dull marry so well? (Anne says she must have Hidden Longings, which is quite revolting, especially when you consider what our stepfather probably looks like sans clothes. I told her surely such things should be outlawed amongst the elderly and besides, ma chérie maman does a very good line in Virgin Queenism–her poor Consort has Jesus to contend with now. I wonder she hasn’t invested in a life-sized crucifix to hang above the bed, now that we are so hideously rich.)

Oh! To Be In London!

I do so long to join you and be in the thick of life at last!

Yours, as always,

Diana xxxx

PS Have just tried to cut my own hair with a pair of sewing shears and now look like the boy who delivers for the butcher’s. Anne has kindly lent me a cloche. Pray for me.

Cate walked up the central staircase, to the large open landing of the first floor. It was galleried, furnished with plush red velvet sofas and end tables. She sat down, gathering herself. There was no need to snap at him, she thought, cradling her head in her hands. She was on edge, that was all.

The truth was she’d assumed Jack would be an older man, a contemporary of Rachel’s; some sexless uncle type who needed a helping hand for a few days. Not a man speeding around in a convertible, staring at her with intense blue eyes, asking questions.

She was safe, she reminded herself. This was England, after all. And here, hidden in this remote house, immersed, like a reluctant time traveller, she was protected, surrounded by the beauty and opulence of another, more elegant age. Nothing could touch her. Least of all a man she hardly knew.

Taking a deep breath, she looked around. It was such a luxurious expanse of space to have at the top of a staircase. People must’ve congregated here, talking, laughing and smoking in their evening clothes before going down to supper. She tried to imagine their easy, urbane conversation; the air a cocktail of French perfume and thick, unfiltered cigarette smoke; flattery and flirtation. Running her hand along, she felt the lush, worn velvet, soft and inviting.

Still, she was tense, unsettled. Getting up, she turned down the hall, looking in each of the rooms until she found what was clearly the master bedroom, with its rich mahogany sleigh bed and dark, masculine furniture. She headed in the opposite direction. All the way at the other end of the long corridor was Lady Avondale’s suite, decorated with lighter, more restrained feminine touches. Soft primrose walls were covered in watercolours, the bed was in the French Empire style and blue-and-white chintz curtains were pulled back across the bay window overlooking the front garden. There was a view of the sea. Someone had opened the windows. Fresh towels were placed neatly on the dresser.

She was expected.

Sitting down on the edge of the bed, she tried to still her racing thoughts. It was useless.

Why was it that no matter how far she travelled from New York, it was never far enough?

Opening her handbag, she took out her phone. The number was withheld. A red light flashed – a message. She threw it back into her handbag. Lying down across the bed she curled into a ball, arms wrapped round her knees.

The room was pretty, elegant, but it offered no comfort. She rolled over on to her back. There was the unfamiliar sound of birdsong. It should’ve been soothing but instead it felt insistent, nagging. She was used to car horns, the roar of traffic; too many people, too close together. Nature felt like a black hole into which she was falling, weightless.

Breathing deeply, she tried to relax, pressing her eyes shut.

But as soon as they were closed, the film began to play again. It always began the same way: with his touch on her skin, the musky scent of his cologne, the pressure of his lips, softly caressing against her bare shoulder…

‘Go on.’ He dipped his finger into the glass of cognac, tracing it along his lips. ‘I dare you.’ He leaned down, his breath warm against her cheek. ‘Kiss me.’

How many times had she promised herself she wouldn’t? She wouldn’t answer his calls; wouldn’t go to him; definitely wouldn’t drink.

He was like an invading army; he didn’t want to love her so much as to occupy her. And to her horror, she wanted to be annihilated; overwhelmed. It took so much for her to feel anything at all.

She flicked her eyes open. These dreams were dangerous.

There were other memories, less palatable; even terrifying. So why was this the one that haunted her? The glamour, seduction; the full force of his desire and attention.

Sitting up, she caught sight of herself in the dressing table mirror on the other side of the room. The slim, blonde woman who stared back was almost unrecognisable, even to her. When she’d first gone to New York, she’d been a brunette, hair halfway down her back, hanging like a veil, hiding her face. Her shoulders were hunched forward, rounding protectively over her solar plexus, which felt permanently tender and bruised.

She wanted to be someone else. Anyone else.

It was Derek Constantine who suggested she cut and dye her hair. ‘Something timeless, classic.’

‘But I can’t afford it.’

‘You can’t afford not to be blonde,’ he corrected her. ‘And,’ he sighed, his upper lip curling slightly as he looked down at her ankle-length skirt, ‘we need to do something about all those black clothes. You’re not an Italian widow. This is a city of very fine social distinctions. Everyone nowadays has money, what’s important is pedigree, exclusivity. You’re like a debutante, before the ball. With proper grooming and introductions to the right people, who knows how far you could go?’

She didn’t understand; it all sounded so conservative and staid. ‘You mean in art?’

His slate-grey eyes were remote, unreadable. ‘In life,’ he answered, pressing the tips of his long fingers together under his chin.

In life.

She blinked back at herself now, two sizes smaller, head to toe in crisp white linen. Clean, controlled, refined. In the hazy afternoon light, she looked golden; angelic.

If only you could remove the darkness of your character with the ease with which you could change your clothes.

He’d sounded so sure, taken such an interest in her. The idea of being guided by this successful, sophisticated man was too compelling to resist. So she hadn’t. Instead she’d abdicated, bit by bit, her faltering, embryonic conception of herself, deferring to his clearer vision and experience.

But the debutante he had in mind wasn’t staid. And the society he introduced her to even less so.

Digging through her bag, she pulled out a pack of cigarettes, and, lighting one, crossed to the open window. She’d given up. She’d given up a lot of things that hadn’t stuck. And she had the feeling, all too familiar nowadays, of trying to stem the tide with a teacup.

I just want peace, she prayed silently, taking a deep drag. Here I am, thousands of miles away from New York, with some strange man, doing a job I know nothing about

…I’m meant to be getting my head together. I’m meant to be figuring out what I want to do with my life.

She pushed her hair back from her face. It was so hot. And everything was baffling.

Suddenly she had an overwhelming desire to get high, to be out of her head, to seduce someone. Pornographic visions filled her brain – a tangle of naked limbs; someone licking her flesh, her mouth travelling across the contours of another body…Her heart seized.

Was it just a fantasy or a flashback?

Naked, she was on her knees in front of him. He was holding her head in his hands, pressing his hips forward…

She bit her lower lip, hard. So hard, it bled. And the desire built, to escape the present moment.

Stop.

She couldn’t stop.

What did Jack look like without his clothes on? They were alone. He was attracted to her, she could feel it. And he was a stranger. Why was it easier to fuck a man you didn’t know?

She exhaled.

Don’t go there.

But a languid sensuality already coursed through her limbs, her imagination spinning like a mirrored top, casting images she couldn’t control. The one thing she shouldn’t think of was the only thing on her mind.

She turned. The bedclothes were torn away, two naked bodies, strangers, reached for one another…If only she could be obliterated, fucked, destroyed.

She closed her eyes. The fantasy dissolved. Taking a last drag, she stubbed out the cigarette and threw it away, into the drive below.

Wandering into the bathroom, she splashed her face with cool water and sat down on the toilet seat. She thought again of the telephone message waiting, with all the others.

It was only a matter of time before she answered one of them.

I am insane, she thought. I’m broken and bad and cannot be fixed.

Covering her face with her hands, she cried.

Jack finished his cup of tea and walked round to the front of the house, unpacking his bag and his equipment, the digital camera and notebooks, from the boot of the car. He caught the faint smell of cigarette smoke and looked up at the open window on the first floor. He smiled. She’d been sneaking a crafty fag!

So, she wasn’t quite as well behaved as she appeared.

It amused him to think of her, only feet away, doing forbidden, clandestine things.

He walked into the house, his footsteps echoing across the cool marble floor, and up the stairs. As he reached the top, a door closed to the right of the landing. So he turned left, heading down the opposite end of the hall. In the master bedroom, he threw his things down on the bed and took off his jacket. Crossing to the open window, he looked out over the lawn.

There was a crackle of anticipation, a tension in the air that he hadn’t felt in years. And it threw him off balance. It was wrong to be excited by this girl; to look forward to standing next to her, to seeing her. Already he was devising possible subjects for dinner conversation; questions and clever little observations that might impress her. He was wound up, he could feel it.

What an idiot!

But in truth, it was terrifying to feel anything again.

He was used to being on his own. It was safe. And he had a routine now. He sat at the same tables in the same cafes, ordered the same food. The waitress remembered how he took his coffee, the owner chatted about the book he was reading. (They knew how to treat a regular customer.) And there were things you could do, if not happily, at least peacefully, quietly – wander around galleries, listen to concerts, sit in the cinema on your own, in the dark. This was his life.

But now, for a moment at least, the seat next to him had been taken. He could still smell her perfume.

Don’t be seduced by the romance of the setting, he reminded himself. It’s about sex, pure and simple. It always was, always would be. It came dressed up as love, passion and romantic obsession, but sooner or later the gilding wore off and the coin underneath was always plain old sex.

Suddenly a memory seeped through his defences. He winced inwardly but couldn’t stop it. He was reaching across to touch his wife, when he saw her face, her large, dark eyes. They were full of sadness and, worse, resignation. He pushed it away but the feeling lingered.

Sex had been unsatisfactory. That was the truth. Reduced to a kind of shorthand, pornographic role play. The act itself wasn’t faked but the connection was, which was worse.

And he hadn’t wanted to discuss it or fix it. That was the awful thing. There’d been a part of him that had found it easier; that wanted to let go. It was as if he’d wished her away.

He was guilty of the crime of withdrawing. She’d seen it and let him go.

That haunted him too.

Jack turned away from the bucolic view.

It was a massive bedroom, practically the size of his entire flat. That’s what you got when you moved out of London – space, beauty, freedom.

He ought to move. He ought to start again somewhere new.

Sinking down on the bed, he yawned, rubbing his eyes.

He ought to do a lot of things.

It wasn’t a long-distance car, his Triumph. His back was stiff from driving. Lying flat, he closed his eyes.

Still, those hours driving across the countryside with Cate by his side were the happiest he’d had in a long time. The sun, the speed, the exuberance of Mozart contrasting with her calm, cool presence. It was exhilarating. He’d felt the hope of happiness; its possibility glimmering on the horizon, like a destination. He hadn’t realised how long he’d lived without the hope of anything, dragging himself mechanically through days, months, years. Now there was an aching in his chest, an animal desire to touch and be touched; to punch his way through the inertia of loss and grief.

He sat up, forced his fingers roughly through his hair.

It was insane to be so taken with this girl. He didn’t even know her.

He was just tired, lonely. Bored.

Still, there were laws of physics, of nature; mysterious, inconvenient gravitational pulls which couldn’t be denied.

At the opposite end of the house, a woman, a complete stranger, was drawing closer all the time.

17, Rue de MonceauParis

24 June 1926

My darling Bird,

You will be pleased to know that I have finally perfected the art of pressing myself up alluringly against a man while dancing and at the same time maintaining an expression of complete and utter indifference verging on contempt. Anne says it is essential and we have been practising it all week. Now all we need are some men.

How is that dashing Baronet of yours? I’m certain his shyness only masks an ardour that will soon make itself known to you (again, details of all carnal encounters kindly requested).

You are probably right that this business of coming out is more difficult and exhausting than I imagine and perhaps, as you say, I would benefit from taking a more serious view of the entire task. But as we both well know, seriousness is not my strong suit. I am, alas, not gifted with your natural good sense but rather destined to be somewhat ridiculous by comparison. I console myself that you have gone before me, made innumerable social contacts and charmed everyone so completely that when I arrive they will simply indulge me as an oddity before packing me off to a remote corner of the Empire with some ageing, palsy-ridden husband in tow.

And yes, I suppose my remarks about our mother are a little cruel. I should be more kind. Especially to Her Consort, the Benefactor of so much Good in our lives.

I know we are lucky, Irene. We certainly have a great deal more than we have ever had. And yet I miss Fa and, if truth be known, I hate Paris and all who sail in her. I am not like you, darling. I am not naturally good or calm or sensible. And I have the feeling of being a fake, everywhere I go–like an actress wandering around onstage in a play she hasn’t read, who can’t recall any of her lines. You seem to understand everything perfectly–why am I such a dolt?

Yours, as always,

The Idiot Child

She tried to nap, but still Cate was restless. She sat up on the bed. It was a vast room, as big as most flats in New York. An entire wall of windows looked out onto a vista of rolling hills, curving dramatically down to the sea.

Who had lived here? Who had chosen these primrose walls, this chintz curtain fabric with its design of blue wisteria and green ivy? This elegant walnut Empire bed? She ran her fingers lightly across the cool linen pillowcase. Its edges were monogrammed, ‘I A’, in pearly silken thread. Was it a wedding gift?

She opened the drawer of the bedside table; it shuddered slightly in protest. Two neatly folded cotton handkerchiefs, a tube of E45 eczema cream, half empty, a few stray buttons, a receipt from Peter Jones in Sloane Square for wool, dated 1989.

Cate closed it and picked up a well-worn volume from the top of a pile of books, The Poems of Thomas Moore, and opened it. On the flyleaf, in a bold flamboyant hand, was written ‘Benedict Blythe, Tir Non Og, Ireland’. It fell open to a page marked by a frayed crimson silk ribbon.

‘Sail On, Sail On’

Sail on, sail on, thou fearless bark –

Where’er blows the welcome wind,

It cannot lead to scenes more dark,

More sad than those we leave behind.

Each wave that passes seems to say,

‘Though death beneath our smile may be,

Less cold we are, less false than they,

Whose smiling wreck’d thy hopes and thee.’

Sail on, sail on – through endless space –

Through calm – through tempest – stop no more.

The stormiest sea’s a resting-place

To him who leaves such hearts on shore.

Or – if some desert land we meet,

Where never yet false-hearted men

Profaned a world, that else were sweet –

Then rest thee, bark, but not till then.’

It was a strange, desolate poem – an unsettling choice for an elderly woman, living out her final days, alone, by the sea.

Putting the book back with the others, Cate peered into the wardrobe. A clutch of naked wire hangers swung in the draught. Apart from a few extra blankets piled on the shelves, it was empty. The same was true of the chest of drawers. Faded flowered lining paper and a few yellowed sachets of potpourri were all that was left.

She turned to the dressing table. A silver brush and comb, a porcelain dish of wiry brown hairpins, a dusty box of Yardley’s lily of the valley talcum powder. And an old black-and-white photograph, presumably of Irene with her husband. She picked it up. They were both in their seventies, standing bolt upright, close but not touching. Irene was thin to the point of physical frailty, wearing a trim straw hat and a dark, neatly tailored suit. Her husband was proudly wearing the full dress uniform of his regiment, a silver-headed walking stick in his right hand; hat tucked under his arm. She was smiling, chin slightly raised, her eyes a distinctive clear blue. It was a bright day, yet the photo was flawed. There was a dark patch, a shadow falling across the right-hand side of the Colonel’s head. It must’ve been taken at a veterans’ event. Irene was holding a plaque of some kind, but the writing on it was too small for Cate to make out.

She wondered where the plaque was now; where all the accolades were that marked Irene Avondale’s lifetime of charitable service to the Empire.

It was a room of order, pleasant and curiously unrevealing, like a stage set. It had a numbing effect as if everything ambiguous had been smoothed over by a large, firm hand. Was Irene’s existence really so tidy and presentable? Or had someone removed any intimate traces of its owner?

Walking out and down the hallway, Cate opened doors, exploring the upper regions of the house. There were equally large bedroom suites both with sea and garden views, bathrooms, dressing rooms, some with floral themes, others with nautical designs…She moved quietly, aware that Jack was resting. She wanted to get a sense of the place on her own, like an animal finding its bearings. Turning in the opposite direction on the landing, she headed down the long hallway that separated the two wings of the house. Dappled sunlight danced in patterns across the faded oriental runners, worn from decades of use. There were two more guest rooms, a large family bathroom and then, at the very end of the hall, a closed door. She turned the knob. It was locked. Jack must have the key.

Cate bent down and examined the old lock. It wasn’t very sophisticated. In fact, it would be easy.

As she headed back to her room, digging out a nail file and credit card from her bag, she knew it would be simpler to wait for him – that it wasn’t really normal to pick the lock. But there was a swell of perversity in her; a childish stubbornness to do what she wanted, when she wanted. The idea of asking for help was inhibiting. And she felt a thrill of defiance as she walked quickly back to the locked door and, in one swift movement, jemmied the latch open.

It was a skill she’d learned from her father when she was eleven – part of an ongoing education that he liked to refer to as ‘life’s little talents’. They included such gems as how to roll a cigarette, the construction of the perfect bacon sandwich, and how to charm virtually anyone with a view to establishing a running tab without any credit at all. After his divorce from her mother, he’d lived in a small Peabody flat near the back of Bond Street Station. A promising guitarist in his youth, his career as a session musician floundered, an unwelcome by-product of his drinking. His once striking good looks faded, worn away by years of self-neglect. His sandy hair and grey-green eyes seemed to lose colour each time she saw him, and his swaggering self-confidence and physical ease were eroded by countless hangovers. She would visit him, and when he was sober, he’d take her for an all-day breakfast and then on to a half-price matinee at the Odeon Cinema in Marble Arch. On a good day, he would seem genuinely pleased to see her; chain-smoking, talking ten to the dozen about the things they would do, the jobs he had in the pipeline, the trips they would take after he next got paid. Maybe Brighton, Europe, perhaps even Africa on safari. Each plan was more magical and ambitious than the next; each promise heartfelt and genuine. When he smiled, he was the most handsome man in the room. ‘This job is different,’ he’d say. ‘This time it’s all coming together.’ And she would believe him.

Then around three o’clock, he would grow inexplicably agitated and irritable. No matter how hard she tried, no matter how many amusing stories she told, she couldn’t keep his attention. And before she knew it, they’d be sitting in a pub. One drink would turn into five, then seven. His face would go hard, his speech began to slur and his whole character would change. He’d lose his keys, misplace his wallet; start a fight with a stranger about some insult only he could hear. And then ‘life’s little talents’ would come in handy as she struggled to get him home without him falling over or getting punched or seducing some ridiculous old barmaid he’d been poking fun of only two hours earlier.

They never did go to Africa or even to Brighton. He spent his life making promises he never kept. Yet she loved him with that stubborn, painful, magical love that children have for their parents. A kind of willing suspension of disbelief that in spite of all of the years of evidence to the contrary, he would somehow, at the very final hour, manage to keep his word. When he died, she felt as if she’d spent her whole life on a train platform, checking her watch in anticipation, waiting for him to arrive. Only he’d been diverted; headed in a different direction entirely. And no one had bothered to tell her.

Perhaps if she’d been more interesting, prettier, smarter…

Now she seemed to have inherited his moral flexibility; his dark, moody restlessness – the same ever-widening discrepancy between her words and actions. Nowadays she too found herself making promises she couldn’t keep, even to herself.

The latch clicked.

The locked door swung open.

Cate blinked, blinded by the brightness.

It was a large square room with high ceilings and a wall of French windows leading to a balcony overlooking the rose garden. All around the room, the most delicate plasterwork and cornicing shone, covered in gilt; bright gold garlands twining against creamy white walls. The effect was dazzling.

Cate stepped out of the cool darkness of the hallway. The room was stifling, airless. She opened the French windows, their hinges creaking from lack of use. Wind rushed in and the vacuum of heat and stale air released like a sigh. It was as if the room were holding its breath. But for how long?

Above a marble fireplace hung an elaborate overmantel. The Aubusson carpet, sun-bleached and pale, was patterned with circlets of flowers and cherries. More garlands wove around the ceiling rose, filling the room with a soft burnished glow. It was easily the loveliest room in the house; beautifully porportioned, ornate, like a miniature ballroom.

So why was it locked?

There was a single bed against one wall and a dresser. A thick layer of dust covered everything. Cate opened a drawer and dust ballooned into the air, making her cough. There was nothing inside.

Bookshelves lined the wall opposite. She examined the faded spines. The Wind in the Willows, The Water-Babies, The Faithless Parrot, The Children of the New Forest as well as Grimm’s Fairy Tales and works by Hans Christian Andersen and a large collection of Lewis Carroll. Pulling out The Wind in the Willows, she opened it. Its spine creaked stiffly. Apart from damage from dust and age, however, it was pristine.

Then, kneeling down, she noticed something. There was an anthology of Beatrix Potter books, small, taking up only half the width of the shelf. Behind them, an old shoebox was wedged into place, filling the gap, making all the rows look even. Cate carefully dislodged it. It was printed in soft brown ink to look as if it were made of alligator skin and tied together with a salmon pink ribbon. It was heavy.

On the side of the box there was a label. ‘F. Pinet, Ladies’ Footwear’. In pencil beneath, written in a florid, old-fashioned hand, there was the shoe size, 4.

Cate untied the frayed silk ribbon and lifted the lid. Wrapped between layers of crumpled newspaper was a pair of delicate silver dancing shoes. They were made from rows and rows of fine braided mesh, finished off with rhinestone clasps. The handiwork was remarkable; intricate patterns of silver thread glittered across the back heel and along the toe. Judging from the style, the roundness of toe, they must have been from the late 1920s or early 1930s. And they looked expensive. Did they belong to Lady Avondale?

Cate turned them over. They’d been worn only a few times; the leather was barely scuffed. She traced her finger along the smooth leather arch. They were so small! Someone, presumably the old lady, used the box to even out the rows of books. But why? Why would anyone bother with such a detail in a room that was locked, virtually empty of furniture?

Picking up the box, she felt something slide to one end. It wasn’t empty. She lifted out the crumpled newspaper.

There, hidden underneath, was a collection of objects.

One by one, she took them out.

There was a worn, pale blue velvet jewellery box. Cate flicked it open.

‘My God!’

It was a tiny bracelet, fashioned from pearls, diamonds and emeralds. ‘Tiffany & Co, 221 Regent Street, W. London’ was printed on the white satin cover of the lid. Cate undid the clasp and held it up to the light. The pattern was a delicate combination of pearl flowers with emerald centres, interspersed with slender pearl ovals augmented by rows of diamonds. The diamonds were dulled by dust and age but the emeralds glittered in the sunlight. She tried it round her own wrist. It only just fitted. Incredibly finely made, it was probably extremely valuable.

Closing the clasp, she laid it neatly back in its case.

Next was a slim silver box with an elaborately scripted ‘B’ in the centre decorated with diamonds. Here was a battered green badge with a picture of a candle on it. It bore the inscription ‘The prize is a fair one and the hope great’, and in the centre were the letters ‘SSG’. A small tarnished brass key, too tiny for any door, had rolled into one corner. It fitted into the hollow of her palm like something from Alice in Wonderland. Perhaps it belonged to a desk or a locked drawer? And at the very bottom of the box, there was a photograph of a handsome dark-haired young man in a sailor’s uniform. He had even features and black, lively eyes. It was a formal photograph, taken in a photographer’s studio. He was posed against a vague classical backdrop of a Greek column, one arm resting casually against a pedestal draped in heavy cloth, the other placed confidently on his hip. ‘HMS VIVID’ was embroidered on his hat. He couldn’t be older than twenty. Underneath, on the black border, the photographer’s name, ‘J. Grey, 33 Union Street, Stonehouse, Plymouth’, was written.

Cate felt a sense of building excitement. This was no random selection of objects but something personal. Each bit – the shoes, the bracelet, the photograph – were related somehow. Someone had gathered them, hidden them in the shoebox, and concealed them behind the books. But why?

A bee flew in through the open French windows. It buzzed wildly, looking for a way out.

She stared at the photograph of the handsome young man with the laughing, defiant gaze.

It was a chronicle, an archive – of something worth hiding – marked by diamonds from Tiffany’s, silver dancing shoes, beautiful young men…

Her memory tripped. Suddenly she was back in time, walking down the long corridor, into the ballroom of the St Regis Hotel, all gilt mirrors and low lighting. People were turning, people she didn’t know, smiling at her, staring. The soft green silk of her dress swirled around her legs. A jazz trio played ‘Please Don’t Talk About Me When I’m Gone’.

Something marked by diamonds, dancing shoes, handsome men…

He was there, in front of her. His hair smooth and glossy, sleek against his strong features; his eyes dark, almost black. He wasn’t handsome but rather compelling; dominating.

‘Some people are afraid of success. Afraid of really being alive.’ His tone was challenging, his expression amused. ‘Are you afraid?’

‘Nothing frightens me,’ she had answered coolly, turning away.

Cate closed her eyes.

In truth she had been afraid; afraid of everything, everyone. But she had lied. She had walked away and he had followed, through the crowds of men and women in evening dress, waltzing and turning, their reflections spinning in the mirrors lining the walls.

The bee veered out of the open window, into the vast freedom of the garden.

Cate watched it disappear.

If only she’d known then that soon he’d be the one walking away and she’d be the one following, stumbling behind.

There was a noise.

Cate tensed as she listened to Jack cross the landing at the end of the hallway.

He was looking for her.

Gathering the things together, she put them back in the box, hastily retying the lid with the ribbon.

It ought to go back where she found it. Or she should show it to Jack.

That was the right thing to do.

‘Cate? Cate?’ He was heading down the stairs. ‘Cate!’ Instead she tucked the box under her arm, racing soundlessly along the corridor, heart pounding, back to her room.

They began their work at the front of the house, with the entrance hall, working fastidiously at what seemed like a painfully slow speed. Little stickers went on each item with a number. Each number corresponded to a description dictated to Cate by Jack and then they took a photograph, sometimes several from different angles. Every figurine, every painting, every detail of the lives that were once lived here were recorded and priced for quick sale.

Each piece had an estimated value. Cate filled in the figures next to the descriptions in uncharacteristically careful, neat handwriting, the total mounting by the minute. It was mind-numbing. How sad that all these objects, acquired and beloved through generations, were to be reduced to nothing but a few lines in a catalogue. Endsleigh had been a home once – a refuge against life and the world. Some of these things had been favourites; treasured. Now she and Jack were the last people ever to stay there in its incarnation as a private home. A couple of strangers; strangers to the house and its history, strangers even to each other. Soon bulldozers would be knocking down Mrs Williams’s low-ceilinged cottage to make way for a luxury spa; the front hallway transformed into a reception area and bar. Already she could imagine the delight of tourists as they arrived for their country-house weekend.

Jack was good at his job, clever and concise, reeling off complicated accounts of styles and conditions of objects without pausing for breath. And Cate was grateful for the lack of demanding interaction between them. He dictated; she recorded. She was invisible and it soothed her to forget for a while who she was and how she’d ended up here. By the time they stopped at seven, her fingers ached from the effort of trying to write clearly and yet at speed.

‘Shall we leave it here for tonight?’ he suggested.

She nodded gratefully, filing away the forms in a folder.

‘I think I can smell something cooking,’ he added, yawning and stretching his arms above his head.

They wandered into the kitchen. Mrs Williams had been hard at work – the shepherd’s pie was browning nicely in the oven and two place settings were laid out on the long pine table along with a green salad, a bowl of fruit and some cheese.

‘Thank God for that!’ He rubbed his hands together. ‘I’m famished!’

‘And yet where is the invisible Mrs Williams?’ Cate wondered, leaning up against the worktop. ‘This is like something out of a fairy tale; Beauty and the Beast.’

‘Don’t we all wish we had staff like that?’

‘Hmm.’

‘Oh, and here’s just the thing!’ Jack picked up a bottle of red wine airing on the worktop next to two glasses. ‘Can I pour you one?’

‘No, thank you.’

‘Really? Are you sure?’

‘I’m fine, thanks.’

Then he remembered his conversation with Rachel, some mention of her father being an alcoholic. Of course, he wasn’t meant to know anything about her. He poured out a glass. ‘I hope you don’t mind.’

‘Why would I mind?’

He shrugged, trying to appear nonchalant. ‘No reason.’

Feeling self-conscious, he smiled and sipped, as if to prove that he was completely ignorant of her family history.

Cate frowned, unable to disguise her irritation. Rachel had obviously been talking. ‘It’s so hot in here!’ She turned away, looking out of the window.

‘You’re right. Let’s eat outside instead.’

‘Fine.’

Once out in the garden, the tension relaxed. It was good to get away from the heat of the kitchen with its ancient Aga. They sat under the chestnut tree again at the same low table where they’d had their tea, carrying the food out on trays.

A cool breeze rustled through the foliage. And suddenly, after the pleasant anonymity of working together for hours, the strangeness of being alone was palpable again.

‘So,’ Cate pushed her food around on her plate, ‘have you always been a valuer?’

It sounded dry and stupid.

Jack looked across at her. ‘No. You’re an artist, aren’t you?’

‘Yes.’ She hadn’t expected him to bat the conversation back at her quite so quickly.

‘What kind of work do you do?’

‘I paint. Reproductions.’

Up shot an eyebrow. ‘Really? You mean Whistler’s Mother and that sort of thing?’

She tore at a piece of bread. ‘I specialise in French and Russian eighteenth-century Romantic painting.’

‘The Enlightenment?’

‘Yes.’

He chuckled.

‘What?’

‘Rachel didn’t tell me you were a faker.’ He looked at her sideways. ‘Ever try to pass anything off?’

‘It’s all real,’ she said, jabbing the bread into a pocket of gravy. ‘It’s just not original. And yes, pieces get “passed off” all the time. Most of the work I do is for insurance purposes. Very few people can afford to lose a masterpiece, even a minor one, to theft or fire.’

‘I’ve offended you. I’m sorry. My mother always told me I had the social skills of a cabbage.’

‘I’m sure she was just being kind.’

He laughed. ‘Mothers are bound to be indulgent. So,’ he tried again, ‘why that period?’

‘I sort of fell into it.’

‘Into the Age of Reason?’

‘Someone asked me to do some work for them. A trompe l’oeil in a quite amazing flat overlooking the park. I found I had a certain aptitude for it. Also, there’s considerably more scope for economic success. After all,’ she took a bite, ‘if you hang a copy of Sunflowers on your wall, everyone knows you’ve got a fake. But if you choose something more elusive, unknown…’

‘Very clever. Was that Constantine’s idea?’

His astuteness caught her off guard. She shifted. ‘Well, the commission did come through a client of his.’

‘He’s always been, shall we say…enterprising.’ He took another sip. ‘And what about your own work?’

‘This is my work.’

‘Of course. I just meant your own subject matter.’

Again, she felt wrong-footed. ‘I get paid very well. And there’s nothing particularly worthy about starving to death in a garret.’

He said nothing. But his expression was amused.

‘This is more sustainable.’

‘Well, yes. We must do what’s sustainable.’

‘Have you always been a valuer?’ she asked again, crisply.

He looked up, grinning. ‘No. My father had an antiques business in Islington. I trained as an auctioneer at Sotheby’s one wayward year after university before I came up with the brilliant idea of becoming an architect. Then, unfortunately, my father became ill. Parkinson’s. And I took over the business.’ He paused. ‘I should’ve sold it and moved on; just been brutal and done it that same year. Instead, I got stuck.’

‘In what way?’

‘Pretending to be my dad, I suppose.’

‘You don’t like it?’

He shrugged his shoulders. ‘A job’s a job, right? And –’ he flashed her a smile – ‘at least it was sustainable. For a while, anyway. I was forced to sell a couple of years later.’

‘How is your father now?’

‘The truth is, it’s hard to tell. One day he’s quite bad and the next he seems like his old self. My mother is thinking of moving him to a nursing home. They live in Leicestershire now and I don’t see them as often as I’d like.’

‘And you never finished your training?’

He stabbed at a bit of salad. ‘I was married by then. To a girl who came into the shop to buy a mirror.’

‘I see. Did you sell her one?’

‘No, she couldn’t afford any. But I made her cups of tea and she used to stop in quite often on the pretext of finding one. In the end I gave her a really quite beautiful Edwardian overmantel.’ He smiled to himself, remembering. ‘I searched high and low for something decent I could afford to part with. I tried to act like I was going to give it away anyway. I don’t think she was fooled.’

‘But she married you. So it worked.’

‘Yes, it worked. I got the girl.’

‘But you sold the shop anyway.’

‘Turns out you need quite a lot of ambition to run your own business. After my wife’s death, I let it go.’ His eyes met hers. ‘She was killed in a car accident, two years ago.’

He said it simply; quickly. She wondered if he’d practised how to get it over with the least amount of emotion possible.

‘I’m so sorry.’

Cool air rushed around them.

‘Yes. Thank you.’

They ate in silence.

‘It’s strange, isn’t it?’ Jack put his fork down. ‘That’s what everyone says – “I’m so sorry.” And I say “Thank you”, like I was buying a pint of milk in a shop. It’s somehow…wrong, inadequate, that it should be reduced to that. And in the end, the whole thing gets reduced down to a single sentence. “That was the year my wife died.”’

She nodded. ‘The whole thing’s an absolute cunt.’

He looked at her in surprise. ‘Yes, well…that’s one way of putting it.’

‘I didn’t mean to offend you.’

‘It makes a change from people apologising.’

‘When my father died, I dreaded speaking to anyone I hadn’t seen in a while; going through the whole dance of clichés. It made me angry. At them, which of course was stupid.’

‘Were you close?’