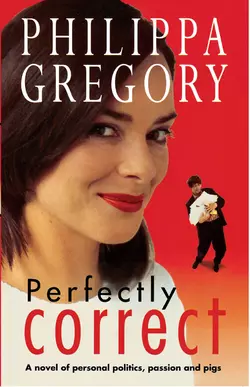

Perfectly Correct

Philippa Gregory

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1036.35 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A witty contemporary satire on the pitfalls of political correctness. From New Men and earnest academics to New Age Travellers and pig farmers, nobody emerges unscathed.Dr Louise Case has the right career, the right country cottage and a commitment-free relationship with a fellow academic. According to contemporary codes, it’s all very correct – except that Louise begins to suspect that it’s far from perfect.Then along comes Rose, eighty if she’s a day, who effortlessly disrupts everything. Soon both campus and cottage are in chaos, while the old lady commences to set her own house – a decrepit old van – in order. And this includes an unthinkably traditional role for Louise…