XPD

XPD

Len Deighton

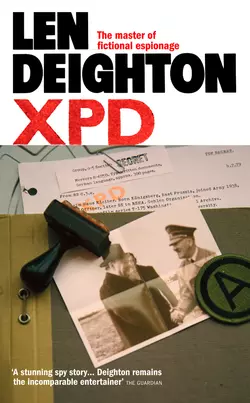

June 11, 1940 – where is Winston Churchill?A private aircraft takes off from a small town in central France, while Adolf Hitler, the would-be conqueror of Europe, prepares for a clandestine meeting near the Belgian border.For more than forty years the events of this day have been Britain’s most closely guarded secret. Anyone who learns of them must die - with their file stamped:XPD - expedient demise

LEN DEIGHTON

XPD

Copyright (#ulink_07c69288-1be6-51d7-8b2c-a7b3b39309b9)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Hutchinson & Co. (Publishers) Ltd 1981

Copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 1981

Introduction copyright © Pluriform Publishing Company BV 2009

Len Deighton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover design © Arnold Schwartzman 2009

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780586054475

Ebook Edition © NOVEMBER 2009 ISBN: 9780007347759

Version: 2017-05-23

Epigraph (#ulink_8cc900d1-937d-5457-bd42-0f89c066cae7)

‘The Second World War produced, in the end, one victor, the United States, one hero, Great Britain, one villain, Germany …’

Hitler, by N. Stone

Table of Contents

Cover (#ue2a7d280-e49a-5838-bfb5-e93b6d3665ab)

Title Page (#u8a76c787-7a3d-5271-837d-ac556625ef9b)

Copyright (#u517f593a-7648-58db-a0eb-c40413acaf44)

Epigraph (#u781337af-4b7d-548e-b181-1cbe81e61aa2)

Introduction (#ufda9ef58-b77f-5866-b1cc-4cbc1f73f4f2)

Chapter 1 (#u3a03e65d-7119-591b-98c3-f6dc1d0b25e4)

Chapter 2 (#ub789c2e1-3f95-5f9c-88cc-febc93c963c3)

Chapter 3 (#u48b1d3e7-52c8-5374-912d-6611bdb2a5c2)

Chapter 4 (#u1500b264-3c02-513d-bb55-a844b728bf55)

Chapter 5 (#u9dd930c5-373b-5e76-b084-780b648bfd0a)

Chapter 6 (#u6f941988-3f61-5a51-95e3-c9b34ac48bb2)

Chapter 7 (#u2f1a467a-99c9-555a-b23f-6c2dabaea353)

Chapter 8 (#u7fcd12ce-7a2f-5624-9bc1-77184721b88d)

Chapter 9 (#udde0224e-728c-5c37-80b6-2d28561e61b0)

Chapter 10 (#u2bb92a32-ab53-59d6-8090-35e69f218624)

Chapter 11 (#u4dcb125d-73ae-5e01-9b5e-0b89c7da660c)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 45 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 46 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 47 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 48 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 49 (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction (#ulink_ad61d6db-1a98-554c-805d-058af529e983)

Adolf Hitler laughed. He threw his head back and his mouth flashed with gold inlays. The onetime manager of Berlin’s grandest movie theatre told me that. Hitler was a movie fan and despite having his private theatre he liked to show himself amid Berlin’s nightlife. Like many despots, he liked to show the world a human side.

Research (whether for history book, cookery books or fiction) is best sought from eye-witness evidence. Historians depend too readily on documents, and my experience is that paperwork is often manipulated by both official and private sources. Talking to participants and appraising their reliability is a test of the historian’s skills. Paperwork is an essential backup for it provides a cross-reference and a context.

Long periods in Austria and Germany – both East and West – enabled me to spend time with many people who had held important positions in the Third Reich. Among them I could count a dozen or more people who had spent time with Hitler face to face. The episodes you will read concerning Hitler’s private train, and about the way the German gold reserves were hidden in the Kaiseroda Mine at Merkers are as authentic as I could make them. I was able to compare German and American eye-witness accounts with material from US archives in Washington DC. Most of what I used was declassified in response to my application. It works like this: you have someone with a high security classification seek out the material you need. That researcher goes to the top to ask for declassified status. It’s a cumbersome business but it was the only way I could obtain the official documentation about the Kaiseroda Mine, which plays a large part in the story you are about to read.

I have only used professional researchers on rare occasions. Research is the fun side of the writing business; why pay someone else to do it? For the episodes in Los Angeles research was simpler and personal. Bill Jordan, a senior figure in LAPD intelligence department, has always been a universally respected policeman. After fighting his way across the Pacific for the Marine Corps, Bill became a familiar figure to Beverly Hills night people as he patrolled that jurisdiction on his Harley Davidson motor cycle. It was Bill who regularly stopped to talk with a young girl sitting on the sidewalk staring into space or sometimes sobbing. That was Marilyn Monroe and she was not the only local resident to owe Bill a debt of gratitude for his care and consideration. In one of those ironic twists that life provides, it was Bill who was the investigating officer for the Bobby Kennedy assassination.

Bill arranged for me to go out at night with the Los Angeles police cars. It wasn’t like the movies and it wasn’t like any of the books I had read, but that time spent with the LA police left me with lasting respect and admiration for these decent young Americans who did this dangerous sort of job night after night.

Despite its shortcomings – and I am coming to those – XPD is one of my favourite books. It was also one of the most successful books I’d written up to that time. And behind the scenes it was one of the most fiercely criticized books too. Not long after publication, a member of the Churchill family wrote a letter of complaint to the publisher. And that wasn’t all: the advertising poster alone – a photo of Hitler shaking hands with Winston Churchill – was enough to have one of the most amusing and energetic members of House of Lords withdraw all copies of XPD from the hundreds of bookshops he controlled. There were cries of censorship and the order was reversed.

The furore caught me completely by surprise. I was in California and I found myself accused of planning a cunning advertising stunt from afar. I did not know whether to be flattered or insulted. I had always been a devout admirer of our wartime prime minister and I remain so. In any case it seemed a sad reflection on our times that these displays of frantic, if not to say antic, indignation were prompted by a story about Churchill attempting to negotiate peace. Could it really be defamatory to say that someone had tried to avoid the chronic misery and tens of millions of deaths of that terrible war?

In fact it was not the plot of XPD that caused the fuss. Hitler and Churchill had been subjected to many worse fates at the hands of ‘faction’ writers. The critics of XPD agreed on one point only; that my story was convincing. It was, they said angrily, written in such a way that readers would believe it. Did they want me to write a story that no one could believe?

This was the first spy story I’d written without the first-person narrative that had set Harry Palmer’s style in The IPCRESS File. In XPD I employed what I believe is called a ‘cosmic’ framework but which nowadays some writers call the ‘omniscient’ style. This is a no-holds-barred device; you can be an authorial nobody or inside everyone’s head, you can move across the world without warning, delve far into the past and even address your reader with personal advice (don’t be scared; I don’t do that). In a first-person story, your hero is on every page whether you want him there or not. Cosmic formats diminish the importance of the central character. Perhaps I did not give him enough tender loving care, for Boyd Stuart is not an endearing hero. This may not have mattered except that I became more and more concerned with the character of Charles Stein.

I grew to like Charles Stein and he wrestled the book away from me. I have always avoided creating unredeemed villains. It’s better, I feel, and more human, to show the best side of the worst characters. Some years before, I had written Declarations of War, a book of war stories in which I polished men of lesser attraction and made them shine. It is a dangerous device but now I found myself doing exactly the same thing with the character of Charles Stein. Eventually it became the Charles Stein book and, looking back on it now, it is how I think of it, and that is why I like it. Hitler and Churchill have only walk-on parts. It is better that way.

Len Deighton, 2009

Chapter 1 (#ulink_083d3679-491e-5a32-8f4e-b40b80d0c3c0)

In May 1979, only days after Britain’s new Conservative government came to power, the yellow box that contains the daily report from MI6 to the Prime Minister was delivered to her by a deputy secretary in the Cabinet Office. He was the PM’s liaison with the intelligence services.

Although the contents of the yellow boxes are never graded into secret, top secret and so on – because all MI6 documents are in the ultra secret category – one rather hastily handwritten report was ‘flagged’. The PM noted with some surprise that it was the handwriting of Sir Sydney Ryden, the director general of MI6, and selected that document for immediate attention. Attached to the corner of it there was an advertisement, clipped from a film journal published in California the previous week.

A film producer, unlisted in any of the department’s reference books, announced that he was preparing what the advert described as ‘A major motion picture with a budget of fifteen million plus!’ It was a Second World War story about plundering German gold in the final days of the fighting. The cutting bore the rubber stamp of ‘Desk 32 Research’ and was signed by the clerk who had found it. ‘What is the final secret of the Kaiseroda mine?’ asked the advertisement. Kaiseroda had been underlined in red pencil to show the word which had alerted the Secret Intelligence Service clerk to the advert’s possible importance.

Normally the space the blue rubber-stamp mark provided for reference would have been filled with a file number but, to his considerable surprise, the research clerk had been referred to no file under the Kaiseroda reference. Instead the Kaiseroda card was marked, ‘To director general only. IMMEDIATE.’

The Prime Minister read carefully through Sir Sydney Ryden’s note, baffled more than once by the handwriting. Then she picked up the telephone and changed her day’s appointments to make a time to see him.

The elderly police constable on duty that afternoon inside the entrance lobby of 10 Downing Street recognized that the man accompanying Sir Sydney was the senior archivist from the Foreign Office documents centre. He was puzzled that he should be here at a time when the PM was so busy settling in but he soon forgot about it. During the installation of a newly elected government there are many such surprises.

The Foreign Office archivist did not attend the meeting between the PM and Sir Sydney, but remained downstairs in the waiting room in case he was required. In the event, he was not.

This was the new Prime Minister’s first official meeting with the chief of the espionage service. She found him uncommonly difficult to talk to: he was distant in manner and overpowering in appearance, a tall man with overlong hair and bushy eyebrows. At the end of the briefing she stood up to indicate that the meeting must end, but Sir Sydney seemed in no hurry to depart. ‘I’m quite certain that there is no truth in these terrible allegations, Prime Minister,’ he said.

He wondered if madam would be a more suitable form of address or perhaps ma’am, as one called the Queen. She looked at him hard and he shifted uncomfortably. Sir Sydney was not an addicted smoker, in the way that his predecessor had been, but now he found the new Prime Minister’s strictures about smoking something of a strain, and longed for a cigarette. In the old days, with Callaghan and before him Wilson, these rooms had seldom been without clouds of tobacco smoke.

‘We’ll discover that,’ said the Prime Minister curtly.

‘I’ll get one of my people out to California within twenty-four hours.’

‘You’ll not inform the Americans?’

‘It would not be wise, Prime Minister.’ He pressed a hand against his ear and flicked back errant strands of his long hair.

‘I quite agree,’ she said. She picked up the newspaper cutting again. ‘For the time being all we need is a straight, simple answer from this film producer man.’

‘That might be rather a difficult task, if my experience of Hollywood film producers is anything to go by.’

The PM looked up from the cutting to see if Sir Sydney was making a joke to which she should respond. She decided not to smile. Sir Sydney did not appear to be a man much given to jesting.

Chapter 2 (#ulink_63bd9599-b5ee-53f6-b59e-325558f4c10f)

The exact details of the way in which the Soviet Union’s intelligence services were alerted to the activities which had so troubled Britain’s Prime Minister is more difficult to piece together. Soviet involvement had begun many weeks earlier and certainly it was the reason behind a long two-part radio message beamed in the early evening of Easter Sunday, 15 April 1979, to the USSR embassy main building on the east side of 16th Street, Washington DC. This unexpected radio transmission required the services of the senior Russian cipher clerk who was enjoying an Easter dinner with Russian friends in a private room at the Pier 7 restaurant on Maine Avenue waterfront near the Capital Yacht Club. He was collected from there by an embassy car.

Intercepted by the National Security Agency, and decoded by its ATLAS computer at Fort George Meade, Maryland, that Sunday evening radio traffic provided the first recorded use of the code name that Moscow had given this operation – Task Pogoni. The written instructions issued in 1962 by the GRU, and later given to the KGB and armed forces, order that the choice of such code names must be such that they do not reveal either the assignment or the government’s intention or attitude, and add a supplementary warning that the code names must not be trivial or of such grandeur that they would attract ridicule should the operation go wrong. And yet, as the NSA translators pointed out in their ‘pink flimsy’ supplementary, Moscow’s choice of code word was revealing.

Literally pogoni means epaulette, but for a citizen of the USSR its implications go deeper than that. Not only can it be used to mean a senior personage or ‘top brass’; it is a symbol of the hated reactionary. ‘Smert zolotopogonnikam!’ cried the revolutionaries, ‘Death to the men who wear gold epaulettes!’ And yet the possible overtones in this choice of the KGB code name can be taken further than that; for nowadays the senior Russian military men who control one of the USSR’s rival intelligence organizations (the GRU) again wear gold epaulettes.

How Yuriy Grechko interpreted the code name assigned to this new operation is not recorded. Grechko – a senior KGB officer – was at the time the USSR’s ‘legal resident’. Using diplomatic cover, it was his job to keep himself, and Moscow, informed on all Soviet espionage activities in the USA. In seniority Grechko ranked a close second to the ambassador himself, and he was there solely to keep all the covert operations and ‘dirty tricks’ entirely separated from official diplomatic business. This made it easier for the ambassador to deny all knowledge of such activities when they were detected by the US authorities.

Grechko was shown in the diplomatic listings as a naval captain third rank, working in the capacity of assistant naval attaché. He was a short man with dry curly hair, blue shiny eyes and a large mouth. His only memorable feature was a gold front tooth which was revealed whenever he smiled. But Grechko did not smile frequently enough for this to compromise his clandestine operations. Grechko was a man who exemplified the Russians’ infinite capacity for melancholy.

It was difficult to reconcile Grechko’s diplomatic listing with his appearance and life-style. His expensive handmade suits, his gold watch, pearl tie-pin, the roll of paper money in his hip pocket, the availability of sports cars and his casual working day all suggested to those men in Washington who are employed to study such details that Grechko was a KGB man, but at this date it was not realized that he was the ‘legal’ – the senior espionage administrator in the embassy.

Since Grechko’s movements were restricted, he summoned his senior secret agent to Washington. It was contrary to the normal procedures, but his radioed instructions had stressed the urgency of his task. Grechko therefore took a trip that morning to the Botanic Gardens on the other side of the Anacostia River. He took his time and made quite sure that he was not being followed when he returned downtown to keep his appointment at the prestigious Hay-Adams Hotel which commands a view across Lafayette Square to the White House.

Mr and Mrs Edward Parker met Grechko at the 16th Street entrance to the hotel where Grechko had booked a table in the name of Green. Edward Parker was a thick-set, bear-like man, with Slavic features: a squarish jaw, wavy grey hair fast becoming white, and bushy eyebrows. He towered over his Japanese wife and Grechko, whose hand he shook with smiling determination. Parker, prepared for Chicago weather, was wearing a heavy tweed overcoat, although Washington that day had temperatures in the high fifties with some sunshine.

Grechko gave Fusako Parker a perfunctory kiss on the cheek and smiled briefly. She was in her middle thirties, a beautiful woman who made the most of her flawless complexion and her doll-like oriental features. She was dressed in a button-through dress of beige-coloured wool, with a large gold brooch in the shape of a chrysanthemum pinned high at the collar. To a casual observer, the three luncheon companions looked typical of the rather conservatively dressed embassy people who crowd into Washington’s best restaurants.

Parker was an importer of components for cheap transistor radios. These were mostly manufactured and partly assembled in Taiwan, Korea and Singapore, where the labour forces were adroit enough to do the work but not yet adroit enough to demand the high wages of the USA and Europe. In this role Parker travelled freely both in the USA and abroad. It was perfect cover for the USSR ‘illegal resident’. Parker was the secret spymaster for the Russian operations in America, with the exception of certain special tasks controlled from the Washington embassy and the extensive ‘Interbloc’ network centred on the United Nations in New York City.

It was 2.20 by the time Grechko finished his cheesecake. When they ordered coffee and brandy, Mrs Parker asked leave to depart to do some shopping before returning to Chicago. Grechko and Parker agreed to this, then the two men began their business discussion.

Parker had been planted in North America for nearly twelve years. His English was more or less faultless and he had easily assumed the bluff and amiable manner of the successful American man of business. Yet Parker had been born a citizen of the USSR and had served for three years with the KGB First Main Directorate’s Scientific and Technical Section before his US assignment. Now he listened with care and attention as Grechko talked rapidly in soft Russian, telling him of the priority that had been given to Task Pogoni. Parker was empowered to assign any of his sleepers to active duty. Such freedom of decision had only five times before been given to the American resident during Parker’s tour of duty. Similar powers had now been provided to the residents in Bonn, Paris and London.

Furthermore, Grechko confided, the First Main Directorate had assigned control to ‘Section 13’. Both men knew what that meant. Although since 1969 it had been renamed the Executive Action Department, what old-timers still call Section 13 of the KGB First Main Directorate handles ‘wet business’ (mokrie dela), which is anything from blackmail through torture to murder. The section was at that time headed by the legendary Stanislav Shumuk, a man highly regarded by the Communist Party’s Administrative Organs Department, from which the KGB is actually controlled. Shumuk would reputedly go to any extreme to provide results.

Parker did not reply. Grechko sipped his black coffee. It was unnecessary to point out that failure could result in unpleasant consequences for both men. After that they resumed conversation in English. It mostly concerned the mechanical problems that Parker had experienced with his wife’s car, which was still under warranty. Parker noticed, not for the first time, that Grechko was a miserable sort of man. It contradicted the stories he had heard about him, and Parker wondered why Grechko should become so despondent only with him.

Mr and Mrs Parker flew back to Chicago on the evening flight. Yuriy Grechko kept an appointment with his girlfriend, a Russian citizen employed by the Trade Delegation. In the early hours of the following morning he was heard arguing loudly with her in a motel where they spent the night just across the state line in Virginia. Grechko had been drinking heavily.

Chapter 3 (#ulink_73056214-b210-5738-84f8-c2813399f3e7)

In spite of his smooth assurances to his Prime Minister, the director general of MI6 did not immediately dispatch an agent to California. The reason for this delay arose out of a conversation that the DG had with his daughter Jennifer. She had a candidate for a task on the far side of the world; her husband.

‘Boyd is being quite beastly,’ she told her father. ‘Not all our friends know we are separated and I have a horror of finding him sitting opposite me at a dinner party. I wish you’d send him to do some job on the far side of the world.’ She gave her father a hug. ‘Just until the divorce is over.’

The DG nodded. He should never have agreed to her marrying a man from his own department, especially such a rootless disrespectful young man. It would have been better to have let the love affair run its course; instead Sir Sydney had pressed them to marry with all the regrettable consequences.

‘He’s on the reassignment list, daddy,’ she coaxed.

Boyd Stuart, a thirty-eight-year-old field agent, had just completed the mandatory one year of ‘administrative duties’ that gave him a small rise in salary before returning him overseas. Such field agents, put behind an office desk in London for twelve months, seldom endear themselves to the permanent staff there. They are often hasty, simplistic and careless with the detail and the paperwork. To this list of deficiencies, Boyd Stuart had added the sin of arrogance. Twelve years as a field agent had made him impatient with the priorities displayed by the staff in London.

‘There is something he could do for us in California,’ said the DG.

‘Oh, daddy. You don’t know how wonderful that would be. Not just for me,’ she added hastily. ‘But for Boyd too. You know how much he hates it in the office.’

The DG knew exactly how much Boyd Stuart hated it in the office. His son-in-law had frequently used dinner invitations to acquaint him with his preference for a reassignment overseas. The DG had done nothing about it, deciding that it would look very bad if he interceded for a close relative.

‘It’s quite urgent too,’ said the DG. ‘We’d have to get him away by the weekend at the latest.’

Jennifer kissed her father. ‘You are a darling,’ she said. ‘Boyd knows California. He did an exchange year at UCLA.’

Boyd Stuart was a handsome, dark-complexioned man whose appearance – like his excellent German and Polish and fluent Hungarian – enabled him to pass himself off as an inhabitant of anywhere in that region vaguely referred to as central Europe. Stuart had been born of a Scottish father and Polish mother in a wartime internment camp for civilians in the Rhineland. After the war, Stuart had attended schools in Germany, Scotland and Switzerland by the time he went to Cambridge. It was there that his high marks and his athletic and linguistic talents brought him under the scrutiny of the British intelligence recruiters.

‘You say there is no file, Sir Sydney?’ Stuart had not had a personal encounter with his father-in-law since that unforgettable night when he had the dreadful quarrel with Jennifer. Sir Sydney Ryden had arrived at four o’clock in the morning and taken her back to live with her parents again.

Stuart was wearing rather baggy, grey flannel trousers and a blue blazer with one brass button missing. It was not exactly what he would have chosen to wear for this encounter but there was nothing he could do now about that. He realized that the DG was similarly unenthusiastic about the casual clothes, and found himself tugging at the cotton strands remaining from his lost button.

‘That is a matter of deliberate policy,’ said the DG. ‘I cannot overemphasize how delicate this business is.’ The DG gave one of his mirthless smiles. This mannerism – mere baring of the teeth – was some atavistic warning not to tread further into sacred territory. The DG stared down into his whisky and then suddenly finished it. He was given to these abrupt movements and long periods of stillness. Ryden was well over six feet tall and preferred to wear black suits which, with his lined, pale face and luxuriant, flowing hair, made him look like a poet from some Victorian romance. He would need little more than a long black cloak to go on stage as Count Dracula, thought Stuart, and wondered if the DG deliberately contrived this forbidding appearance.

Without preamble, the DG told Stuart the story again, shortening it this time to the essential elements. ‘On 8 April 1945, elements of the 90th Division of the United States Third Army under General Patton were deep into Germany. When they got to the little town of Merkers, in western Thuringia, they seat infantry into the Kaiseroda salt mine. Those soldiers searched through some thirty miles of galleries in the mine. They found a newly installed steel door. When they broke through it they discovered gold; four-fifths of the Nazi gold reserves were stored there. So were two million or more of the rarest of rare books from the Berlin libraries, the complete Goethe collection from Weimar, and paintings and prints from all over Europe. It would take half an hour or more to read through the list of material. I’ll let you have a copy.’

Stuart nodded but didn’t speak. It was late afternoon and sunlight made patterns on the carpet, moving across the room until the bright bars slimmed to fine rods and one by one disappeared. The DG went across to the bookcases to switch on the large table lamps. On the panelled walls there were paintings of horses which had won famous races a long time ago, but now the paintings had grown so dark under the ageing varnish that the strutting horses seemed to be plodding home through a veil of fog.

‘Just how much gold was four-fifths of the German gold reserves?’ Stuart asked.

The DG sniffed and ran a finger across his ear, pushing away an errant lock of hair. ‘About three hundred million dollars’ worth of gold is one estimate. Over eight thousand bars of gold.’ The DG paused. ‘But that was just the bullion. In addition there were three thousand four hundred and thirty-six bags of gold coins, many of which were rarities – coins worth many times their weight in gold because of their value to collectors.’

Stuart looked up and, realizing that some response was expected, said, ‘Yes, amazing, sir.’ He sipped some more of the whisky. It was always the best of malts up here in the DG’s office at the top of ‘the Ziggurat’, the curious, truncated, pyramidal building that looked across the River Thames to the Palace of Westminster. The room’s panelling, paintings and antique furniture were all part of an attempt to recapture the elegance that the Secret Intelligence Service had enjoyed in the beautiful old houses in St James’s. But this building was steel and concrete, cheap and practical, with rust stains dribbling on the façade and cracks in the basement. The service itself could be similarly described.

‘The American officers reported their find through the usual channels,’ said the DG, suddenly resuming his story. ‘Patton and Eisenhower went to see it on 12 April. The army moved it all to Frankfurt. They took jeeps and trailers down the mine and brought it out. Ingenious people, the Americans, Stuart.’ He smiled and held the smile while looking Stuart full in the eyes.

‘Yes, sir.’

‘It took about forty-eight hours of continuous work to load the valuables. There were thirty crates of German patent-office records – worth a king’s ransom – and two thousand boxes of prints, drawings and engravings, as well as one hundred and forty rolls of oriental carpets. You see the difficulties, Stuart?’

‘Indeed I do, sir.’ He swirled the last of his drink round his glass before swallowing it. The DG gave no sign of noticing that his glass was empty.

‘They were ordered to begin loading the lorries just two days after Eisenhower’s visit. The only way to do that was simply by listing whatever was on the original German inventory tags. It was a system that had grave shortcomings.’

‘If things were stolen, there was no way to be sure that the German inventory had been correct in the first place?’

The DG nodded. ‘Can you imagine the chaos that Germany was in by that stage of the war?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Quite so, Stuart. You can not imagine it. God knows what difficulties the Germans had moving all their valuables in those days of collapse. But I assure you that the temptation for individual Germans to risk all in order to put some items in their pockets could never have been higher. Perhaps only the Germans could have moved such material intact in those circumstances. As a nation they have a self-discipline that one can only admire.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘As soon as the Americans captured the mine, its contents went by road to Frankfurt, and were stored in the Reichsbank building. A special team from the State Department were given commissions overnight, put into uniform and flown from Washington to Frankfurt. They sifted that material to find sensitive papers or secret diplomatic exchanges that would be valuable to the US government, or embarrassing to them if made public. After that it was all turned over to the Inter-Allied Reparations Agency.’

‘And was there such secret material?’

‘Let me get you another drink, Stuart. You like this malt, don’t you? With water this time?’

‘Straight please, sir.’

The DG gave another of his ferocious grins.

‘Of course there was secret material. The exchanges between the German ambassador in London and his masters in Berlin during the 1930s would have caused a few red faces here in Whitehall, to say nothing of red faces in the Palace of Westminster. Enough indiscretions there to have put a few of our politicians behind bars in 1940 … members of Parliament telling German embassy people what a splendid fellow Adolf Hitler was.’

The DG poured drinks for them both. He used fresh cut-glass tumblers. ‘Something wrong with that door, Stuart?’

‘No, it’s beautiful,’ said Stuart, admiring the antique panelling. ‘And the octagonal oak table must be early seventeenth century.’

The DG groaned silently. It was not the sort of remark expected of the right sort of chap. Ryden had been brought up to believe that a gentleman did not make specific references to another man’s possessions. He had always suspected that Boyd Stuart might be ‘artistic’ – a word the DG used to describe a wide variety of individuals that he blackballed at his club and shunned socially. ‘No ice? No soda? Nothing at all in it?’ asked the DG again, but he marred the solicitude by descending into his seat as he said it.

Stuart shook his head and raised the heavy tumbler to his lips.

‘No,’ agreed the DG. ‘With a fine Scots name such as Boyd Stuart a man must not be seen watering a Highland malt.’

‘Not in front of a Sassenach,’ said Stuart.

‘What’s that? Oh yes, I see,’ said the DG raising a hand to his hair. Stuart realized that his father-in-law wore his hair long to hide the hearing aid. It was a surprising vanity in such a composed figure; Stuart noted it with interest. ‘Oxford, Stuart?’

Stuart looked at him for a moment before answering. A man who could commit to memory all the details of the Kaiseroda mine discoveries was not likely to forget where his son-in-law went to university. ‘Cambridge, sir. Trinity. I read mathematics.’

The DG closed his eyes. It was quite alarming the sort of people the department had recruited. They would be taking sociologists next. He was reminded of a joke he had heard at his club at lunch. A civil service candidate made an official complaint: he had missed promotion because at the civil service selection board he had admitted to being a socialist. The commissioner had apologized profoundly – or so the story went – he had thought the candidate had admitted to being a sociologist.

Boyd Stuart sipped his whisky. He did not strongly dislike his father-in-law – he was a decent enough old buffer in his way. If Ryden idolized his daughter so much that he could not see her faults, that was a very human failing.

‘Was it Jennifer’s idea?’ Stuart asked him. ‘Sending me to California, was that her idea?’

‘We wanted someone who knew something about the film trade,’ said Sir Sydney. ‘You came to mind immediately …’

‘You mean, had it been banking, backgammon or the Brigade of Guards,’ said Stuart, ‘I might have been trampled in the rush.’

The DG smiled to acknowledge the joke. ‘I remembered that you studied at the UCLA.’

‘But it was Jennifer’s idea?’

The DG hesitated rather than tell a deliberate untruth. ‘Jennifer feels it would be better … in the circumstances.’

Stuart smiled. He could recognize the machinations of his wife.

‘Little thought you’d find yourself in this business when you were at Trinity, eh Stuart?’ said the DG, determined to change the subject.

‘To tell you the absolute truth, sir, I was hoping to be a tennis professional.’

The DG almost spluttered. He had a terrible feeling that this operation was going to be his Waterloo. He would hate to retire with a notable failure on his hands. His wife had set her mind on his getting a peerage. She had even been exploring some titles; Lord and Lady Rockhampton was her current favourite. It was the town in Australia in which her father had been born. Sir Sydney had promised to find out if this title was already taken by someone. He rather hoped it was.

‘Yes, a fascinating game, tennis,’ said the DG. My God. And this was the man who would have to be told about the ‘Hitler Minutes’, the most dangerous secret of the war. This was the fellow who would be guarding Winston Churchill’s reputation.

‘The convoy of lorries left Merkers to drive to Frankfurt on 15 April 1945,’ said the DG, continuing his story. ‘We think three, or even four, lorries disappeared en route to Frankfurt. None of the valuables and the secret documents on them were ever recovered. The US army never officially admitted the loss of the lorries but unofficially they said three.’

‘And you think that this film company in California now have possession of the documents?’

The DG went to the window, looking at the cactus plants that were lined up to get the maximum benefit from the light. He picked one pot up to examine it closely. ‘I can assure you quite categorically, Stuart, that we are talking about forgeries. We are talking about mythology.’ He sat down, still holding the plant pot and touching the soil carefully.

‘It’s something that would embarrass the government?’

The DG sniffed. He wondered how long it would take to get his message across. ‘Yes, Stuart, it is.’ He put the cactus on the coffee table and picked up his drink.

‘Are we going to try to prevent this company from making a film about the Kaiseroda mine and its treasures?’ Stuart asked.

‘I don’t give a tinker’s curse about the film,’ said the DG. He patted his hair nervously. ‘But I want to know what documentation he has access to.’ He drank some of his whisky and glanced at the skeleton clock on the mantelpiece. He had another meeting after this and he was running short of time.

‘I’m not sure I know exactly what I’m looking for,’ Stuart said.

The DG stood up. It was Stuart’s cue to depart. In the half-light, his lined face underlit by the table lamp, and his huge, dark-suited figure silhouetted against the dying sun, Ryden looked satanic. ‘You’ll know it when you see it. We’ll keep in contact with you through our controllers in California. Good luck, my boy.’

‘Thank you, sir.’ Stuart rose too.

‘You’ve seen Operations? Got all the procedures settled? You understand about the money – it’s being wired to the First Los Angeles Bank in Century City.’ The DG smiled. ‘Jennifer tells me you are giving her lunch tomorrow.’

‘There are some things she wants from the flat,’ explained Stuart.

‘Get to California as soon as possible, Stuart.’

‘There are just a few personal matters to settle,’ said Stuart. ‘Cancel my holiday arrangements and stop the milk.’

The DG looked at the clock again. ‘We have people in the department who will attend to the details, Stuart. We can’t have operations delayed because of a few bottles of milk.’

Chapter 4 (#ulink_7c688aef-6fac-5abb-90bb-5c67a8c20c21)

‘We have people in the department who will attend to the details, Stuart,’ said Boyd Stuart in a comical imitation of the DG’s voice.

Kitty King, Boyd Stuart’s current girlfriend, giggled and held him closer. ‘So what did you say, darling?’

‘Not this gorgeous little detail they won’t, I told him. Some things must remain sacred.’ He patted her bottom.

‘You fool! What did you really say?’

‘I opened my mouth and poured his whisky into it. By the time I’d finished it, he’d disappeared through the floor, like the demon king in the pantomime.’ He kissed her again. ‘I’m going to Los Angeles.’

She wriggled loose from his grasp. ‘I know all about that,’ she said. ‘Who do you think typed your orders this afternoon?’ She was the secretary to the deputy chief of Operations (Region Three).

‘Will you be faithful to me while I’m away?’ said Stuart, only half in fun.

‘I’ll wash my hair every night, and go early to bed with Keats and hot cocoa.’

It was an unlikely promise. Kitty was a young busty blonde who attracted men, young and old, as surely as picnics bring wasps. She looked up, saw the look on Stuart’s face and gave him a kiss on the end of his nose. ‘I’m a child of the sexual revolution, Boyd darling. You must have read about it in Playboy?’

‘I never read Playboy; I just look at the pictures. Let’s go to bed.’

‘I’ve made you that roasted eggplant dip you like.’ Kitty King was a staunch vegetarian; worse, she was an evangelistic one. Amazing, someone at the office had remarked after seeing her in a bikini, to think that it’s all fruit and nuts. ‘You like that, don’t you.’

‘Let’s go to bed,’ said Stuart.

‘I must turn off the oven first, or my chickpea casserole will dry up completely.’

She backed away from him slowly. In spite of the disparity in their ages, she found him disconcertingly attractive. Until now her experiences with men had been entirely under her control but Boyd Stuart, in spite of all his anxious remarks, kept her in her place. She was surprised and annoyed to discover that she rather liked the new sort of relationship.

She looked at him and he smiled. He was a handsome man: the wide, lined face and the mouth that turned down at one side could suddenly be transformed by a devastating smile, and his laugh was infectious.

‘Your chickpea casserole!’ said Boyd Stuart. ‘We don’t want that to dry up, darling.’ He laughed a loud, booming laugh and she could not resist joining in. He put out his hand to her. She noticed that the back of it was covered with small scars and the thumb joint was twisted. She had asked him about it once but he had made some joke in reply. There was always a barrier; these men who had worked in the field were all the same in this respect. There was no way in which to get to know them completely. There was always a ‘no entry’ sign. Always some part of their brain was on guard and awake. And Kitty King was enough of a woman to want her man to be completely hers.

Boyd Stuart pushed open the door of the bedroom. It was the best room in the apartment in many ways: large and light, like so many of these rambling Victorian houses near the river on the unfashionable side of Victoria Station. That was why he had a writing desk in a window space of his bedroom, a corner which Kitty King liked to refer to grandiosely as ‘the study’.

‘Kitty!’ he called.

She came into the bedroom, leaned back against the door and smiled as the latch clicked.

‘Kitty. The lock of my desk is broken.’ He opened the inlaid walnut front of the antique bureau. The lock had been torn away from the wood and there were deep scratches in the polished surface. ‘You didn’t break into it, did you, Kitty?’

‘Of course not, Boyd. I’m not interested in your old love letters.’

‘It’s not funny, Kitty. I have classified material in here.’ Already he was sifting through the drawers and pigeonholes. He found the airline ticket, his passport, the letter to the bank, a couple of contact addresses and an old photo of a man named Bernard Lustig cut from a film trade magazine. There was also a newspaper cutting that he had been given by the department.

An all-expenses-paid trip to the movie capital of the world and the luxury of the exclusive Beverly Hills Hotel.

Veterans of the US Third Army and attached units who were concerned with the movement of material from the Kaiseroda salt mine, Merkers, Thuringia, Germany, in the final days of the Second World War are urgently sought by B. Lustig Productions Inc. The corporation is preparing a major motion picture about this historical episode. Veterans should send full details, care of this newspaper, to Box 2188. Photos and documents will be treated with utmost care and returned to the sender by registered post.

Kitty King watched him search through the items.

‘Nothing seems to have been taken,’ said Stuart. ‘Did you leave the door open when you went down to the dustbin?’

‘There was no one on the stairs,’ she said.

‘Waiting upstairs,’ said Stuart. ‘The same kid who did the burglaries in the other flats, I’ll bet.’

‘Are you going to phone the department?’

‘Nothing’s missing. And the front door has no signs of forced entry.’

‘The papers for your trip were there, weren’t they?’

He nodded.

‘Then you must have known about going last Sunday – when you put the tickets and things in there.’ There was a note of resentment in her voice.

‘I still wasn’t sure until I saw the DG late this afternoon.’

‘I wish you’d discussed it with me, Boyd.’ He looked up sharply. This was a new side of Kitty King. She had always described their relationship as no more than a temporary ‘shack-up’. She was a career woman, she had always maintained, with a good degree in political science from the London School of Economics, and the aim of becoming a Permanent Secretary, the top of the Administrative Class grades.

Stuart said, ‘If I phone the night duty officer, they’ll be all over us. You know what a fuss they’ll make. We’ll be up all night writing reports.’

‘You know best, sweetheart.’

‘A kid probably, looking for cash. When he found only this sort of thing he got out quickly, before you came back upstairs again.’

‘Does your wife still have her key to this place?’ Kitty asked.

‘She wouldn’t break open my desk.’

‘That’s not what I asked you.’

‘It was just some kid looking for cash. Nothing is missing. Stop worrying about it.’

‘She’d like to get you back, Boyd. You realize that, don’t you?’

Boyd put his arms round her tightly and kissed her for a long time.

Chapter 5 (#ulink_d087dbf9-81b4-52c7-a39b-629a07c168c4)

The Steins – father and son – lived in a large house in Hollywood. Cresta Ridge Drive provides a sudden and welcome relief from the exhaust fumes and noise of Franklin Avenue. It is one of a tangle of steep winding roads that lead into the Hollywood hills and end at Griffith Park and Lake Hollywood. Its elevation gives the house a view across the city, and on smoggy days when the pale tide of pollution engulfs the city, the sky here remains blue.

By Californian standards these houses are old, discreetly sited behind mature horse-chestnut trees now grown up to the roofs. In the thirties some of them, their gardens blazing with hibiscus and bougainvillea as they were this day, had been owned by film stars. Even today long-lost but strangely familiar faces can be glimpsed at the check-out of the Safeway or self-serving gasoline at Wilbur’s. But most of Stein’s neighbours were corporate lawyers, ambitious dentists and refugees from the nearby aerospace communities.

On this afternoon a rainstorm deluged the city. It was as if nature was having one last fling before the summer.

Outside the Steins’ house there was a white Imperial Le Baron two-door hardtop, one of the biggest cars in the Chrysler range. The paintwork shone in the hard, unnatural light that comes with a storm, and the heavy rain glazed the paintwork and the dark tinted windows. Sitting – head well down – in the back seat was a man. He appeared to be asleep but he was not even dozing.

The car’s owner – Miles MacIver – was inside the Stein home. Stein senior was not at home, and now his son Billy was regretting the courtesy he had shown in inviting MacIver into the house.

MacIver was a well-preserved man in his late fifties. His white hair emphasized the blue eyes with which he fixed Billy as he talked. He smiled lazily and used his large hands to emphasize his words as he strode restlessly about the lounge. Sometimes he stroked his white moustache, or ran a finger along an eyebrow. They were the gestures of a man to whom appearance was important: an actor, a womanizer or a salesman. MacIver possessed attributes of all three.

It was a large room, comfortably furnished with good quality furniture and expensive carpets. MacIver’s restless prowling was proprietorial. He went to the Bechstein grand piano, its top crowded with framed photographs. From the photos of friends and relatives, MacIver selected a picture of Charles Stein, the man he had come to visit, taken at the training battalion at Camp Edwards, Massachusetts, sometime in the early 1940s. Stein was dressed in the uncomfortable, ill-fitting coveralls which, like the improvised vehicle behind him, were a part of America’s hurried preparations for war. Stein leaned close to one side of the frame, his arm seemingly raised as if to embrace it.

‘Your dad cut your Uncle Aram out of this picture, did he?’

‘I guess so,’ said Billy Stein.

MacIver put the photo back on the piano and went to look out of the window. Billy had not looked up from where he was reading Air Progress on the sofa. MacIver studied the view from the window with the same dispassionate interest with which he had examined the photo. It was a glimpse of his own reflection that made him smooth the floral-patterned silk tie and rebutton his tartan jacket.

‘Too bad about you and Natalie,’ he said without turning from the window. His voice was low and carefully modulated – the voice of a man self-conscious about the impression he made.

The warm air from the Pacific Ocean was heavy, saturated with water vapour. It built up towering storm clouds, dragging them up to the mountains, where they condensed, dumping solid sheets of tropical rain across the Los Angeles basin. Close to the house, a tall palm tree bent under a cruel gust of wind that tried to snap it in two. Suddenly released, the palm straightened with a force that made the fronds dance and whip the air loudly enough to make MacIver flinch and move from the window.

‘It lasted three months,’ said Billy. He guessed his father had discussed the failure of his marriage and was annoyed.

‘Three months is par for the course these days, Billy,’ said MacIver. He turned round, fixed him with his wide-open eyes and smiled. In spite of himself, Billy smiled too. He was twenty-four years old, slim, with lots of dark wavy hair and a deep tan that continued all the way to where a gold medallion dangled inside his unbuttoned shirt. Billy wore thin, wire-rimmed, yellow spectacles that he had bought during his skiing holiday in Aspen and had been wearing ever since. Now he took them off.

‘Dad told you, did he?’ He threw the anti-glare spectacles on to the coffee table.

‘Come on, Billy. I was here two years ago when you were building the new staircase to make a separate apartment for the two of you.’

‘I remember,’ said Billy, mollified by this explanation. ‘Natalie was not ready for marriage. She was into the feminist movement in a big way.’

‘Well, your dad’s a man’s man, Billy. We both know that.’ MacIver took out his cigarettes and lit one.

‘It was nothing to do with dad,’ Billy said. ‘She met this damned poet on a TV talk show she was on. They took off to live in British Columbia … She liked dad.’

MacIver smiled the same lazy smile and nodded. He did not believe that. ‘We both know your dad, Billy. He’s a wonderful guy. They broke the mould when they made Charlie Stein. When we were in the army he ran that damned battalion. Don’t let anyone tell you different. Corporal Stein ran that battalion. And I’ll tell you this …’ he gestured with his large hands so that the fraternity ring shone in the dull light, ‘I heard the colonel say the same thing at one of the battalion reunions. Charlie Stein ran the battalion. Everyone knew it. But he’s not always easy to get along with. Right, Billy?’

‘You were an officer, were you?’

‘Captain. Just for the last weeks of my service. But I finally made captain. Captain MacIver; I had it painted on the door of my office. The goddamned sergeant from the paint shop came over and wanted to argue about it. But I told him that I’d waited too goddamned long for that promotion to pass up the right to have it on my office door. I made the signwriter put it on there, just for that final month of my army service.’ He gestured again, using the cigarette so that it left smoke patterns in the still air.

Billy Stein nodded and pushed his magazine aside to give his full attention to the visitor. ‘Is it true you pitched for Babe Ruth?’

‘Your dad tell you, did he?’ MacIver smiled.

‘That was when you were at Harvard, was it, Mr MacIver?’ There was something in Billy Stein’s voice that warned the visitor against answering. He hesitated. The only sound was the rain; it hammered on the windows and rushed along the gutterings and gurgled in the rainpipes. Billy stared at him but MacIver was giving all his attention to his cigarette.

Billy waited a long time, then he said, ‘You were never at Harvard, Mr MacIver; I checked it. And I checked your credit rating too. You don’t own any house in Palm Springs, nor that apartment you talked about. You’re a phoney, Mr MacIver.’ Billy Stein’s voice was quiet and matter of fact, as if they were discussing some person who was not present. ‘Even that car outside is not yours – the payments are made in the name of your ex-wife.’

‘The money comes from me,’ snapped MacIver, relieved to find at least one accusation that he could refute. Then he recovered himself and reassumed the easy, relaxed smile. ‘Seems like you out-guessed me there, Billy.’ Effortlessly he retrenched and tried to salvage some measure of advantage from the confrontation. The only sign of his unease was the way in which he was now twisting the end of his moustache instead of stroking it.

‘I guessed you were a phoney,’ said Billy Stein. There was no satisfaction in his voice. ‘I didn’t run any check on your credit rating; I just guessed you were a phoney.’ He was angry with himself for not mentioning the money that MacIver had had from his father. He had come across his father’s cheque book in the bureau and found the list of six entries on the memo pages at the back. More than six thousand dollars had been paid to MacIver between 10 December 1978 and 4 April 1979, and every cheque was made out to cash payment. It was that that had encouraged Billy’s suspicion.

‘I ran into a tough period last autumn; suppliers needed fast repayment and I couldn’t meet the deadlines.’

‘The diamonds that you bought here in town and sent to your contact man in Seoul?’ said Billy scornfully. ‘Was it five thousand per cent on every dollar?’

‘You’ve got a good memory, Billy.’ He smoothed his tie. ‘You’d be a tough guy to do business with. I wish I had a partner like you. I listen to these hard-luck stories from guys who owe me money and I melt.’

‘I bet,’ said Billy. Fierce gusts pounded the windows and made the rain in the gutters slop over and stream down the glass. There was a crackle of static like brittle paper being crushed, and a faint flicker of lightning lit the room. The sound silenced the two men.

Billy Stein stared at MacIver. There was no malevolence in his eyes, no violence nor desire for argument. But there was no compassion there either. His private income and affluent life-style had made Billy Stein intolerant of the compromises to which less fortunate men were forced. The exaggerations of the old, the half-truths of the poor and the misdemeanours of the desperate found no mitigation in Billy Stein’s judgement. And so now Miles knew no way to counter the young man’s calm judicial gaze.

‘I know what you’re thinking, Billy … the money I owe your father. I’m going to pay every penny of it back to him. And I mean within the next six weeks or so. That’s what I wanted to see him about.’

‘What happens in six weeks?’

Miles MacIver had always been a careful man, keeping a careful separation between the vague confident announcements of present or future prosperity – which were invariably a part of his demeanour – and the more stringent financial and commercial realities. But, faced with Billy Stein’s calm, patronizing inquiry, MacIver was persuaded to tell him the truth. It was a decision that was to change the lives of many people, and end the lives of several.

‘I’ll tell you what happens in six weeks, Billy,’ said MacIver, hitching his trousers at the knees and seating himself on the armchair facing the young man. ‘I get the money for the movie rights of my war memoirs. That’s what happens in six weeks.’ He smiled and reached across to the big china ashtray marked Café de la Paix – Billy’s father had brought it back from Paris in 1945. He dragged the ashtray close to his hand and flicked into it a long section of ash.

‘Movie rights?’ said Billy Stein, and MacIver was gratified to have provoked him at last into a reaction. ‘Your war memoirs?’

‘Twenty-five thousand dollars,’ said MacIver. He flicked his cigarette again, even though there was no ash on it. ‘They have got a professional writer working on my story right now.’

‘What did you do in the war?’ said Billy. ‘What did you do that they’ll make it into a movie?’

‘I was a military cop,’ said MacIver proudly. ‘I was with Georgie Patton’s Third Army when they opened up this Kraut salt mine and found the Nazi gold reserves there. Billions of dollars in gold, as well as archives, diaries, town records and paintings … You’d never believe the stuff that was there.’

‘What did you do?’

‘I was assigned to MFA & A, G-5 Section – the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives branch of the Government Affairs Group – we guarded it while it was classified into Category A for the bullion and rare coins and Category B for the gold and silver dishes, jewellery, ornaments and stuff. I wish you could have seen it, Billy.’

‘Just you guarding it?’

MacIver laughed. ‘There were five infantry platoons guarding the lorries that moved it to Frankfurt. There were two machine-gun platoons as back-up, and Piper Cub airplanes in radio contact with the escort column. No, not just me, Billy.’ MacIver scratched his chin. ‘Your dad never tell you about all that? And about the trucks that never got to the other end?’

‘What are you getting at, Mr MacIver?’

MacIver raised a flattened hand. ‘Now, don’t get me wrong, Billy. No one’s saying your dad had anything to do with the hijack.’

‘One of dad’s relatives in Europe died during the war. He left dad some land and stuff over there; that’s how dad made his money.’

‘Sure it is, Billy. No one’s saying any different.’

‘I don’t go much for all that war stuff,’ said Billy.

‘Well, this guy Bernie Lustig, with the office on Melrose … he goes for it.’

‘A movie?’

MacIver reached into his tartan jacket and produced an envelope. From it he took a rectangle of cheap newsprint. It was the client’s proof of a quarter-page advert in a film trade magazine. ‘What is the final secret of the Kaiseroda mine?’ said the headline. He passed the flimsy paper to Billy Stein. ‘That will be in the trade magazines next month. Meanwhile Bernie is talking up a storm. He knows everyone: the big movie stars, the directors, the agents, the writers, everyone.’

‘The movie business kind of interests me,’ admitted Billy.

MacIver was pleased. ‘You want to meet Bernie?’

‘Could you fix that for me?’

‘No problem,’ said MacIver, taking the advert back and replacing it in his pocket. ‘And I get a piece of the action too. Two per cent of the producer’s profit; that could be a bundle, Billy.’

‘I couldn’t handle the technical stuff,’ said Billy. ‘I’m no good with a camera, and I can’t write worth a damn, but I’d make myself useful on the production side.’ He reached for his anti-glare spectacles and toyed with them. ‘If he’ll have me, that is.’

MacIver beamed. ‘If he’ll have you! … The son of my best friend! Jesusss! He’ll have you in that production office, Billy, or I’ll pull out and take my story somewhere else.’

‘Gee, thanks, Mr MacIver.’

‘I call you Billy; you call me Miles. OK?’ He dug his hands deep into his trouser pockets and gave that slow smile that was infectious.

‘OK, Miles.’ Billy snapped his spectacles on.

‘Rain’s stopping,’ said MacIver. ‘There are a few calls I have to make …’ MacIver had never lost his sense of timing. ‘I must go. Nice talking to you, Billy. Give my respects to your dad. Tell him he’ll be hearing from me real soon. Meanwhile, I’ll talk to Bernie and have him call you and fix a lunch. OK?’

‘Thanks, Mr MacIver.’

‘Miles.’ He dumped his cigarettes into the ashtray.

‘Thanks, Miles.’

‘Forget it, kid.’

When Miles MacIver got into the driver’s seat of the Chrysler Imperial parked outside the Stein home, he sighed with relief. The man in the back seat did not move. ‘Did you fix it?’

‘Stein wasn’t there. I spoke with his son. He knows nothing.’

‘You didn’t mention the Kaiseroda mine business to the son, I hope?’

MacIver laughed and started the engine. ‘I’m not that kind of fool, Mr Kleiber. You said don’t mention it to anyone except the old man. I know how to keep my mouth shut.’

The man in the back seat grunted as if unconvinced.

Billy Stein was elated. After MacIver had departed he made a phone call and cancelled a date to go to a party in Malibu with a girl he had recently met at Pirate’s Cove, the nude bathing section of the state beach at Point Dume. She had an all-over golden tan, a new Honda motorcycle and a father who had made a fortune speculating in cocoa futures. It was a measure of Billy Stein’s excitement at the prospect of a job in the movie industry that he chose to sit alone and think about it rather than be with this girl.

At first Billy Stein spent some time searching through old movie magazines in case he could find a reference to Bernie Lustig or, better still, a photo of him. His search was unrewarded. At 7.30 the housekeeper, who had looked after the two men since Billy Stein’s mother died some five years before, brought him a supper tray. A tall, thin woman, she had lost her nursing licence in some eastern state hospital for selling whisky to the patients. Perhaps this ending to her nursing career had changed her personality, for she was taciturn, devoid of curiosity and devoid too of that warm, maternal manner so often associated with nursing. She worked hard for the Steins but she never attempted to replace that other woman who had once closed these same curtains, plumped up the cushions and switched on the table lamps. She hurriedly picked up the petals that had fallen from the roses, crushed them tightly in her hand and then dropped them into a large ashtray upon MacIver’s cigarette butt. She sniffed; she hated cigarettes. She picked up the ashtray, holding it at a distance as a nurse holds a bedpan.

‘Anything else, Mr Billy?’ Her almost colourless hair was drawn tightly back, and fixed into position with brass-coloured hair clips.

Billy looked at the supper tray she had put before him on the coffee table. ‘You get along, Mrs Svenson. You’ll miss the beginning of “Celebrity Sweepstakes”.’

She looked at the clock and back to Billy Stein, not quite sure whether this concern was genuine or sarcastic. She never admitted her obsession for the TV game shows but she had planned to be upstairs in her self-contained apartment by then.

‘If Mr Stein wants anything to eat when he gets home, there is some cold chicken wrapped in foil on the top shelf of the refrigerator.’

‘Yes, OK. Good night, Mrs Svenson.’

She sniffed again and moved the framed photo of Charles Stein which MacIver had put back slightly out of position amongst the photos crowding the piano top. ‘Good night, Billy.’

Billy munched his way through the bowl of beef chilli and beans, and drank his beer. Then he went to the bookcase and ran a fingertip along the video cassettes to find an old movie that he had taped. He selected Psycho and sat back to watch how Hitchcock had set up his shots and assembled them into a whole. He had done this with an earlier Hitchcock film for a college course on film appreciation.

The time passed quickly, and when the taped film ended Billy was even more excited at the prospect of becoming a part of the entertainment world. He found show-biz stylish and hard-edged: stylish and hard-edged being compliments that were at that time being rather overworked by Billy Stein’s friends and contemporaries. He rewound the tape and settled back to see Psycho once more.

Charles Stein, Billy’s father, usually spent Wednesday evenings at a club out in the east valley. They still called it the Roscoe Sports and Bridge Club, even though some smart, real-estate man had got Roscoe renamed Sun Valley, and few of the members played anything but poker.

Stein’s three regular cronies were there, including Jim Sampson, an elderly lawyer who had served with Stein in the army. They ate the Wednesday night special together – corned beef hash with onion rings – shared a few bottles of California Gewürztraminer and some opinions of the government, then retired to the bar to watch the eleven o’clock news followed by the sports round-up. It was always the same; Charles Stein was a man of regular habits. A little after midnight, Jim Sampson dropped him off at the door – Stein disliked driving – and was invited in for a nightcap. It was a ritual that both men knew, a way of saying thank you for the ride. Jim Sampson never came in.

‘Thought you had a heavy date tonight, Billy?’ Charles Stein weighed nearly 300 pounds. The real crocodile-leather belt that bit into his girth and bundled up his expensive English wool suit and his pure cotton shirt was supplied to special order by Sunny Jim’s Big Men’s Wear. Stein’s sparse white hair was ruffled, so that the light behind him made an untidy halo round his pink head as he lowered himself carefully into his favourite armchair.

Billy, who never discussed his girlfriends with his father, said, ‘Stayed home. Your friend MacIver dropped in. He thinks he can get me a job in movies.’

‘Get you a job in movies?’ said his father. ‘Get you a job in movies? Miles MacIver?’ He searched in his pocket to find his cigars, and put one in his mouth and lit it.

‘They’re making a movie of his war memoirs. Some story! Finding the Nazi gold. Could be a great movie, dad.’

‘Hold the phone,’ said his father wearily. He was sitting on the edge of the armchair now, leaning well forward, his head bent very low as he prepared to light his cigar. ‘MacIver was here?’ He said it to the carpet.

‘What’s wrong?’ said Billy Stein.

‘When was MacIver here?’

‘You said never interrupt your poker game.’

‘When?’ He struck a match and lit his cigar.

‘Five o’clock, maybe six o’clock.’

‘You watching TV tonight?’

‘It’s just quiz shows and crap. I’ve been running video.’

‘MacIver is dead.’ Charles Stein drew on the cigar and blew smoke down at the carpet.

‘Dead?’

‘It was on Channel Two, the news. Some kid blew off the top of his head with a sawed-off shotgun. Left the weapon there. It happened in one of those little bars on Western Avenue near Beverly Boulevard. TV news got a crew there real quick … cars, flashing lights, a deputy chief waving the murder weapon at the camera.’

‘A street gang, was it?’

‘Who then threw away a two-hundred-dollar shotgun, all carefully sawed off so it fits under your jacket?’

‘Then who?’

Charles Stein blew smoke. ‘Who knows?’ he said angrily, although his anger was not directed at anyone in particular. ‘MacIver the Mouth, they called him. Owes money all over town. Could be some creditor blew him away.’ He drew on the cigar again. The smoke tasted sour.

‘Well, he sold his war memoirs. He showed me the advertisement. Some movie producer he met. He’s selling him a story about Nazi gold in Germany in the war.’

Charles Stein grunted. ‘So that’s it, eh? I wondered why that bastard had been going around talking to all the guys from the outfit. Sure, I saw a lot of him in the army but he wasn’t even with the battalion. He was with some lousy military police detail.’

‘He’s been getting the story from you?’

‘From me he got nothing. We were under the direct order of General Patton at Third Army HQ for that job, and we’re still not released from the secrecy order.’ He ran his fingers back through his wispy hair and held his hand on the top of his head for a moment, lost in thought. ‘MacIver has been writing all this stuff down, you say, and passing it to some movie guy?’

‘Bernie Lustig. MacIver was going to introduce me to him,’ said Billy. ‘Poor guy. Was it a stick-up?’

‘He won’t be doing much in the line of introductions, Billy. By now he’s in the morgue with a label on his toe. Lustig – where’s he have his office?’

‘Melrose – he hasn’t made it to Beverly Hills or even to Sunset. That’s what made me think it was true … If MacIver had been inventing this guy, he would have chosen somewhere flashier than Melrose.’

‘Go to the top of the class, Billy.’ He eased off his white leather shoes and kicked them carelessly under the table.

‘What was he like, this MacIver guy?’ MacIver had now achieved a posthumous interest, not to say glamour. ‘What was he really like, dad?’

‘He was a liar and a cheat. He sponged on his friends to buy drinks for his enemies … MacIver was desperate to make people like him. He’d do anything to win them over …’ Stein was about to add that MacIver’s promise to get Billy a job in the movie industry was a good example of this desperate need, but he decided not to disappoint his son until more facts were available. He smoked his cigar and then studied the ash on it.

‘Did you know him in New York, before you went into the army?’

‘He was from Chicago. He was on the force there, working the South Side – a tough neighbourhood. He leaned heavily on the “golden-hearted cop” bit. He joined the army after Pearl Harbor and gave them all that baloney about being at Harvard. There was no time to check on it, I suppose …’

‘It was baloney. He as good as admitted it.’

‘They wouldn’t let MacIver into Harvard to haul the ashes. Sure it was baloney, but it got him a commission in the military police. And he used that to pull every trick in the book. He was always asking for use of one of our trucks. A packing case delivered here; a small parcel collected here. He got together with the transport section and the rumours said they even sold one of our two-and-a-half-tonners to a Belgian civilian and went on leave in Paris to spend the proceeds.’ Suddenly Stein felt sad and very tired. He wiped a hand across his face, as a swimmer might after emerging from the water.

‘What are you going to do now, dad?’

‘I lost five hundred and thirty bucks tonight, Billy, and I’ve put away more white wine than is good for my digestion …’ He coughed, and looked for his ashtray without finding it. In spite of all his reservations about MacIver, he was shocked by the news of his murder. MacIver was a con-man, always ready with glib promises and the unconvincing excuses that inevitably followed them. And yet there were good memories too, for MacIver was capable of flamboyant generosity and subtle kindness, and anyway, thought Charles Stein, they had shared a lifetime together. It was enough to make him sad, no matter what kind of bastard MacIver had been.

‘You going to find this Bernie Lustig character?’ said Billy.

‘Is that the name of the movie producer?’

‘I told you, dad. On Melrose.’

‘I guess so.’

‘You don’t think this Lustig cat had anything to do with the killing, do you?’

‘I’m going to bed now, Billy.’ Again he looked for the ashtray. It was always on the table next to the flower vase.

‘If he owed MacIver twenty-five thousand dollars …’

‘We’ll talk about it in the morning, Billy. Where’s my ashtray?’

‘I’ll catch the TV news,’ said Billy. ‘Think they’ll still be running the clip?’

‘This is a rough town, Billy. One killing don’t make news for long.’ He reached across the table and stubbed his cigar into the remains of Billy’s beans.

Chapter 6 (#ulink_267aa223-5fc7-5980-a643-138c0bcb32bc)

The man behind the desk could have been mistaken for an oriental, especially when he smiled politely. His face was pale and even the sunshine of southern California made his skin go no darker than antique ivory. His hair was jet black and brushed tight against his domed skull. ‘Max Breslow,’ he said, offering a hand which Charles Stein shook energetically.

‘I was expecting to meet Mr Bernie Lustig,’ said Stein. He had selected one of his most expensive cream-coloured linen suits but already it was rumpled, and the knot of his white silk tie had twisted under his collar. He lowered his massive body into the black leather Charles Eames armchair, which creaked under his weight.

‘Mr Lustig is in Europe,’ said Max Breslow. ‘There is work to do there for our next production.’

‘The final secret of the Kaiseroda mine?’ said Stein, waving his large hand in the air and displaying a heavy gold Rolex watch and diamond rings on hands that were regularly manicured. When Breslow did not react to this question, Stein said, ‘Mr Miles MacIver is an old friend of mine. He promised to get my son a job with your film.’ Breslow nodded. Stein corrected himself. ‘MacIver was a close friend of mine.’

‘You were in the army with him?’ He had a faint German accent.

‘I didn’t say that,’ said Stein. He stroked his sideburns. They were long and bushy, curling over his ears.

Breslow picked up a stainless-steel letter-opener, toyed with it for a moment and looked at Stein. ‘It was a sad business with Mr MacIver,’ said Breslow. He said it with the same sort of clinical indifference with which an airline clerk comforts a passenger who has lost his baggage.

Stein remembered MacIver with a sudden disconcerting pang of grief. He recalled the night in 1945 when MacIver had crawled into the wreckage of a German Weinstube. They were in some small town on the other side of Mainz. The artillery had long since pounded it flat, the tanks had bypassed its difficult obstacles, the infantry had forgotten it existed, the engineers had threaded their tapes all through the streets, and left ‘DANGER BOOBY TRAPS’ signs in the rubble. Stein remembered how MacIver had climbed down from their two-and-a-half-ton winch truck saying that goddamned engineers always put those signs on the booze joints so they could come back and plunder it in their own sweet time. Stein had held his breath while MacIver climbed over the rubble and across the wrecked front parlour of the wine bar. For a moment he had been out of sight but soon he reappeared, flush-faced and grinning in triumph, fingers cut on broken glass and sleeve dark and wet with spilled red wine that shone like fresh blood. He was struggling under the weight of a whole case of German champagne.

MacIver had eased a cork and it had hit the roof of the cab with a noise like a gunshot. They poured it into mess tins and drank the fiercely bubbling golden champagne without talking. When they had finished it, MacIver tossed the empty bottle out into the dark night. ‘It’s a long time between drinks, pal.’

‘For an officer, and a flatfoot, you’re a scorer,’ said Stein.

It was a hell of a thing for an officer to do. A long time between drinks; he could never hear that said without thinking of MacIver.

‘I beg your pardon,’ said Breslow politely. His head was cocked as if listening to some faint sound. Stein realized that he’d spoken out loud.

‘It’s a long time between drinks,’ said Stein. ‘It’s an American saying. Or at least it used to be when I was young.’

‘I see,’ said Breslow, noting this interesting fact. ‘Would you like a drink?’

‘OK,’ said Stein. ‘Rum and Coke if you’ve got it.’

Breslow rolled his swivel chair back towards the wall so that he could open the small refrigerator concealed in his walnut desk.

‘It’s darned hot in here,’ said Stein. ‘Is the air-conditioner working?’ His weight made him suffer in the humidity and now his hand-stitched suit showed small dark patches of sweat.

Breslow set up paper napkins and glasses on his desk top and put ice into one of them before adding the rum and Coke. He did it fastidiously, using metal tongs, one cube at a time. For himself he poured a small measure of cognac, without ice.

Stein had been nursing a floppy straw hat. As he eased himself slowly from the low armchair to get his drink from the desk, he tossed his hat on to a side table where film trade magazines had been arranged in fan patterns.

He didn’t get his drink immediately; going to the window he looked out. Melrose came close to the freeway here in one of the older districts of the city. This office was an apartment in a two-storey block repainted bright pink. Across the street brick apartment buildings and dilapidated little offices were defaced with obscene Spanish graffiti and speared with drunken TV antennae, and the whole thing was birdcaged with overhead wires. The freeway traffic was moving very slowly so that the Hollywood hills beyond wobbled in a grey veil of diesel fumes. Stein pulled his sunglasses from his face and pushed them into the top pocket of his jacket. He blinked in the bright light and dabbed his face with a silk handkerchief. ‘Damned hot.’ The sun was blood red and its light came through the slats of the venetian blind to make a pattern across Stein’s wrinkled face. It was always like this the day after a bad storm.

‘I’ve spoken to the janitor,’ explained Breslow. ‘The repairmen are working on the air-conditioning. Yesterday’s heavy rain got into the mechanism.’

‘MacIver owed me money,’ said Stein, ‘a lot of money. He gave me a part of his interest in your movie as surety.’