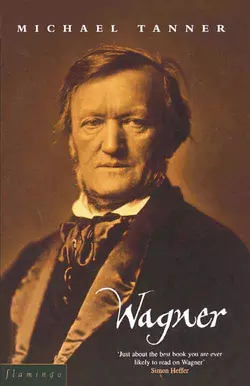

Wagner

Michael Tanner

‘A fine, intellectually sparkling and always engaging little book – a welcome addition to any Wagner library’Hans Vaget, Opera QuarterlyWhilst no one would dispute Wagner’s ranking among the most significant composers in the history of Western music, his works have been more fiercely attacked than those of any other composer. His supposed personal defects have provoked intense hostility which has translated into a mistrust and abhorrence of his music. Tanner’s fascination for the relationship between music, text and plot generates and illuminating discussion of the operas, in which he persuades us to see many of Wagner’s best-know works afresh. His passionate and unconventional analyses are accessible to all lovers of music, be they listeners or performers.Note that it has not been possible to include the same picture content that appeared in the original print version.

Wagner

Michael Tanner

For Elisabeth Furtwängler

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#u026de11f-62f2-5c4e-99d5-e46e05b7487a)

Title Page (#ua0c4d8b9-9315-54cd-ae10-b68793536d4f)

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#u966fcc47-232a-527d-beca-13fb0d11207a)

1 The Case of Wagner (#u46c2e36a-4b77-55ec-aadd-4474fb98843f)

2 Prejudices and Banalities (#ub9ff7798-0196-56cb-9e96-9fef2aa816f4)

3 Getting under Way (#uec8e27af-ba8d-5cff-9a86-4ae7a65b1c7d)

4 Domesticating Wagner (#u4fde906b-c019-5fdf-a572-a3d7ce81cfdc)

5 Grandeur and Suffering in Wagner: Some Case Studies (#litres_trial_promo)

6 Lohengrin and its Prelude (#litres_trial_promo)

7 Wagner Ponders (#litres_trial_promo)

8 What is the Ring About? (#litres_trial_promo)

9 Men and Gods (#litres_trial_promo)

10 The Fearless Hero (#litres_trial_promo)

11 The Passion of Passion (#litres_trial_promo)

12 Art, Tradition and Authority (#litres_trial_promo)

13 The Ring Resumed (#litres_trial_promo)

14 Redemption to the Redeemer (#litres_trial_promo)

15 Postlude: Wagner and Culture (#litres_trial_promo)

CHRONOLOGY (#litres_trial_promo)

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY (#litres_trial_promo)

INDEX (#litres_trial_promo)

Tolstoy’s Diaries (#litres_trial_promo)

Music and the Mind (#litres_trial_promo)

Epstein (#litres_trial_promo)

Dr Johnson & Mr Savage (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#ulink_a119cd8a-f8fd-5d91-b26a-4527b9dd1e23)

This book is intended for people who have some, not necessarily very much, acquaintance with Wagner’s operas and who feel that they raise questions which are both urgent and difficult. The sensuous appeal of Wagner’s art is very powerful, but it also, and oddly, seems to be highly intellectual. And, as reading anything about Wagner soon reveals, it gives rise to a great deal of polemic, much of it soon taking one away from the works themselves and onto the personality that created them, and to broad cultural issues. For an artist who has been dead for more than a century, Wagner’s position is uniquely unstable. I want to investigate why that should be so, to put the central points in the arguments as forcefully as I can, and while not disguising the fact that I am a passionate admirer of his work, to see why so many people who are musically and culturally quite catholic in their tastes find his art repellent.

There are no musical technicalities in this book, which means that it is not an explanation of how Wagner gains his effects, but rather an exploration of what they are. Nor have I given plot summaries of the music dramas, since they are available in many books (see Select Bibliography), and in the booklets which accompany most recordings of the works.

I have discussed Wagner with countless people over a period of more than forty years. Many of those discussions have no doubt contributed to the views which I now have about his work. But the only acknowledgements which need to be made are to my friend Brian Jones, who encouraged me at a crucial stage of writing this book, and discussed its shape, and many specific points, at a length which amazed us both, but which was unquestionably beneficial. I owe him an incalculable debt; and to Frank Kermode, who asked me to write the book, and was most encouraging and patient about it. The same applies to Stuart Proffitt, who showed in extreme measure the mixture of forbearance and keenness to see the finished item which one hopes for from a publisher.

Michael Tanner

Cambridge, August 1995

1 The Case of Wagner (#ulink_9ec17ab3-ac8b-5b64-a7e9-4b320914b9fb)

What is it about Richard Wagner that makes him, 112 years after his death, still so violently controversial? The easy answer would be ‘Everything’, but it would not be quite right. For no one – no serious musician – any longer doubts that his place among the most significant composers is now secure. That, at least, is a comparatively recent development. Until after the Second World War, which certainly did his reputation no good, and for which, to read some contemporary commentators, one might think he was in large measure responsible, there were still important figures on the musical scene who were prepared confidently to dismiss him out of hand.

But one would be hard put to it now to find that attitude. It becomes increasingly difficult to write off someone whose works remain enormously popular all over the world, whole cycles of the Ring, however outlandish the production and mediocre the musical execution, being invariably sold out in advance; and much more so now than half a century ago. Among the musical avant-garde his fate has been more complex: after a period in which many of them, Stravinsky being their leading spokesman (but even he finally recanted), regarded him as a tiresome perversion in the history of music, they have increasingly tended to find him a cause of extreme fascination, and even of inspiration. That has been especially true of the aggressive modernists of the post-World War II era, Boulez and Stockhausen. The latter is still in the process of writing a vast cycle of operas which he knows will routinely be dubbed Wagnerian, on account of their scope, ambition and pretensions. Boulez has devoted lengthy periods of an exceptionally varied and trend-setting career to conducting Wagner, and to writing about him in favourable terms, though his writings seem to urge on us the strange request that we, at long last, come to view Wagner ‘objectively’. But how can we, and how can anyone, imagine that we ever will?

We have the phrase ‘to put someone in perspective’, and we use it in an odd way. For since it has become fashionable, at any rate in philosophical circles, to use the term ‘perspectivism’, and rather less fashionable to have much of an idea of what that term might mean, people have begun to deny, on what sound like fresh grounds, the possibility of objective truth. And yet when they talk of putting Wagner, or for that matter anyone else, in perspective, they seem to mean getting an accurate idea of him as opposed to being infatuated with or violently contemptuous of him. But there is, if one understands what a perspective is, no such thing as getting someone, and a fortiori not Wagner, into it. There is only the possibility of taking various perspectives, and seeing how he looks from them. What, I think, is meant is achieving a desirable distance from Wagner, being locked in neither embrace nor combat. But what is that distance, and how would we know that we had achieved it? We are back already, too soon, at objectivity, with its connotations of lack of involvement, a capacity for seeing something – Wagner’s works, or the whole gigantic phenomenon of works together with life together with influence of many kinds – without taking sides, though we may pass judgement, of a desirably impersonal kind.

A short book which began with a long consideration of methodology might be tiresome, so I shall take as a kind of motto some sentences from Hans Keller’s book Criticism:

But ever since the age of objectivity started, primarily in reaction to so-called romantic hero-worship, this new danger has, as a temptation, presented itself to the evaluating, the critical historian – to canalise his own destructiveness into a professional virtue and, inspired by the spirit of detachment, find fault especially where impeccability used to reign.

In the entire history of the Western mind, one chief villain has emerged in the age of objectivity, for a variety of reasons, all of them easy to uncover – RICHARD WAGNER.

(Criticism, p. 95)

That does seem undeniable, though I’m not sure about the ease with which all the reasons for Wagner’s status can be uncovered. As Keller goes on to say, even lovers of Wagner’s music are often haters of Wagner the man, some of them plainly finding something exciting about the contrast in their feelings. And haters of the music often claim that it was written by the kind of person you would expect, granted what it is they hate about it. Music critics, and perhaps opera critics in particular, as we shall see, tend to be naive about the relationship between composers and their art. And even if they aren’t in general, when it comes to Wagner the tendency to infer objectionable features in the work from (alleged) detestable personal characteristics proves too strong to withstand, for anyone who dislikes the works in the first place.

Hans Keller goes on to offer his own diagnosis of anti-Wagnerism. But while he makes many shrewd points, it seems to me that he doesn’t get to the heart of the matter. His chief claim is that we have a dread of greatness, that the ‘age of objectivity’, about which he is efficiently scathing, has supervened on an age of hero-worship, which we now view with embarrassment and distaste. While it is not uncommon to find a need to cut geniuses, especially self-conscious ones, down to size, that doesn’t provide a sufficient explanation of anti-Wagnerism, since there are other geniuses whom almost everyone rejoices in celebrating. Mozart is an obvious case, even now that the myth of his childlike unawareness of his gifts has been pretty comprehensively blown. And though Beethoven is a more controversial figure, I think that that is not on account of his insistence on the respect due to his genius.

The fact is that people would forgive Wagner his alleged megalomania, his genuine anti-Semitism, his (ludicrously exaggerated) womanising, his conversion from left revolutionary to right nationalist, and anything else known or suspected about him, if they didn’t find something in his music-dramas, perhaps more specifically in his music, which led them to reinforce their hostility by grasping at anything about him that might justify their Miss Prism-style moralising. And though the hostility, or the expression of it, often takes forms so shockingly crude that one is tempted to ignore it, it is important to recognise that its roots are deep. Too deep, it seems, for exploration by those who indulge – still – in hysterical denunciation.

Hans Keller has an explanation, one which has been adumbrated by other favourably disposed writers, for this too:

Wagner’s music [Keller was only interested in the dramas to the extent that they enabled Wagner to express his supreme musical gifts], like none other before or after him, let what Freud called the dynamic unconscious, normally inaccessible, erupt with a clarity and indeed seductiveness which will always be likely to arouse as much resistance (to the listener’s own unconscious) as its sheer power creates enthusiasm.

The trouble with that highly plausible-sounding suggestion is that no one has succeeded in developing it any further, no doubt because to do so would involve independent research of a kind that musicologists are unwilling or unable to undertake; and because, as usual with explanations which derive from Freud, it is hard to know how to set about verifying or falsifying them, even in rough outline. Is the suggestion that those of us who respond passionately to Wagner in a favourable way are unusually well-balanced, or exceptionally neurotic? And that those who find his music repulsive are repressed or threatened by what it audaciously succeeds in exposing?

It seems that the argument could go either way. It is satisfying to Wagnerians to feel that they can cope with uniquely explicit revelations of the contents of their unconscious, and it is satisfying to anti-Wagnerians to feel that they are rejecting the glorification of barbaric forces. This argument, like all serious argument about Wagner, had already been launched by Nietzsche, who, I think it is interesting and relevant to note in this crucial matter, is not illuminating, at any rate in any direct way, in his early pro-Wagnerian writings, but who becomes hugely instructive in his late expressions of fear and loathing. Without having available the resources of Freudian terminology and what it denotes, he had made a claim which can very easily be translated into psychoanalytic terms. It was a general claim about art, which received, he thought, spectacular justification from studying the rampant Wagnerism by which he felt himself to be surrounded, and which not long before he had fervently endorsed.

The claim is that, for the healthy person, art serves to express his sense of over-abundance, extreme vitality, everything to which Nietzsche opposed ‘decadence’. By contrast, for the decadent himself – Wagner being the arch-example – art expresses need, lack, an urgent demand and supply in one, making up in fantasy for what is missing in reality. The claim applies equally to the artist and to his audience. It is, quite evidently, questionable in the most straightforward sense, and all the more so because it is so central a claim about civilisation, society, and the various forms which they take. So the Kellerclaim that Wagner has a uniquely direct line to the ‘dynamic unconscious’, and is therefore, though a deeply disturbing artist, also a very great one, had been pre-stated by Nietzsche to Wagner’s disadvantage. Wagner gets to the places which no other artist does, but for the Wagnerian that is felt as a liberating, exhilarating experience: Where id was, ego is, when one is listening to Tristan und Isolde, say, and it is Tristan which is always the touchstone for Nietzsche. But the anti-Wagnerian of Nietzsche’s outlook can only lament the neurotic state which Tristan appears to cure, and the embracing of the art which deals with it successfully, or seems to. For the Nietzsche of the late phase art which treats illness is itself sick, and there is no hope for those who need it. Art is, Nietzsche had come to think, either celebration of health or comfort for the ailing. It no longer possesses the truth-value which it had done for him in his heady days as a Wagnerian: that he should ever have thought such a thing shows what a plight he had been in. Art is no vehicle of truth, though it may be highly symptomatic, and so inadvertently give away a lot. Whatever one can deduce from art, it is not a revelation of a reality apart from the artist and his audience, as it had been in The Birth of Tragedy. Because it is now, for Nietzsche, nothing but an experience sui generis, it is impossible to live by it. That is the hideous mistake the Wagnerian makes, and can hardly fail to in succumbing to those hypnotic, narcotic works. As for living, Wagner does that for the Wagnerian; but the anti-Wagnerian does it for himself, or at any rate makes a spirited attempt.

This is still speculative, nebulously so. Yet it would be less than honest for people on either side to deny that something, maybe a large element, in their responses to Wagner is touched by it; at least on repeatedly interrogating my own feelings about him I conclude that it is a line worth pressing on with. The difficulty is that, as in any matter which goes so deep, it ramifies so extensively that it is hard to deal with without also articulating one’s reactions to a large number of the most basic issues. All to the good, in one way. But the problem now becomes that while for the Wagnerian it is an excellent and enjoyable thing to be able to focus his attitudes towards many of his central preoccupations by further experiences of Wagner’s art, and reflection on them, for the anti-Wagnerian it is painful, or worse still, merely boring, not stimulating, to be led to define his positions by reference to a phenomenon which he finds so cosmically nasty and tiresome. So confrontation at this profound level, which could be most worthwhile, because most searching, tends not to occur. Instead there is endless bickering about aspects of Wagner and his art which is interesting, possibly, but serves to disguise the real conflicts which should be explored, and so the whole discussion is superficial, if impassioned.

It would be different if Wagner were only an artist, whatever exactly that means; or if he had been clearly in the first place something else – a philosopher of culture, or some kind of prophetic figure. But he was, and remains, a musical dramatist trailing clouds of doctrine, and thus a ‘phenomenon’. In the former case, he could be just ignored as not to the taste of many ardent lovers of music and drama; in the latter, attacked or ridiculed for the falsity or absurdity of his views. It is the cunning interpenetration of his art and his prosily expressed Weltanschauung which makes him unavoidable, together with his immense influence in so many disparate spheres. No wonder that those who resist take refuge in unrestrained polemic – they want to obliterate him, so that he can simply cease to exist as the object of endless discussion. But their polemics only fuel counterblasts, and achieve just the opposite effect from the ‘marginalising’ which they had hoped for. In his own last, splenetic writings on Wagner, Nietzsche acknowledged that too. There is, and will remain, a ‘case of Wagner’ so long as we are stuck in the cultural crisis which Nietzsche diagnosed, because Wagner embodies it to an extent which no other artist approaches.

The issue is complicated by a further one which makes Wagner’s music-dramas very different from almost everything else in the operatic tradition, Schoenberg being the only notable exception. Wagner was intensely concerned that we should feel rather than think in the presence of his works. Here at least his hope has been fulfilled. But for many people, whom for convenience’s sake we may call Brechtians, that in itself renders him suspect. However, it is worth noticing that they attack Wagner not so much for saying that he wanted emotional rather than cognitive responses to his art, but for the works themselves, which seem to demand an incessantly high-level emotional response more insistently than any others. But the Brechtians don’t attack Verdi, for instance, in the same way, or so far as I know at all, despite the fact that his operas provide stimulus for feeling rather than thought – indeed the idea of thinking in relation to Verdi is odd. Who could reflect for long, and relevantly, on Il Trovatore, a masterpiece of its kind, but one which can only excite and move us in presenting with such vigour a succession of situations each of which is stirring? Wagner is the most intellectual of musical dramatists (Schoenberg again excepted, and up to a point Pfitzner in his explicitly Wagnerian masterpiece Palestrina); not by dint of the prodigious theoretical writings and continuous musings, in correspondence and conversation, about everything under the sun, if not indeed the sun itself; but by virtue of the subject-matter of his works and the kinds of issue which his characters are involved in and are articulate about. Sometimes in Wagner’s works it seems as if he were setting philosophical dialogues to music, the victory being awarded not to the character who argues most convincingly, but to the one who, to put it not quite accurately, has the best tunes.

In fact one can say that Wagner would not have been so insistent that we should respond by feeling rather than by thinking if he hadn’t realised the extraordinarily dense quality of the thinking which is going on in both the words and the actions of his dramas. The relationship between thought, or ‘reason’ or ‘intellect’ (the German word is ‘Verstand’) as Wagner more often puts it, and feeling, was something which he wasn’t so inclined to be simple-minded about as what I have thus far said suggests. He devotes a long section of his major theoretical work, Opera and Drama, to the subject, and produces many penetrating and novel formulations, of which perhaps the most subtle can be illustrated by this quotation:

Nothing should remain for the synthesising intellect to do in the face of a performance of a dramatic work of art; everything presented in it must be so conclusive that our feeling about it is brought to rest; for in the bringing to rest of this feeling, after its highest arousal in sympathy with it, lies that very peace which leads us to the instinctive understanding of life. In drama we must become knowers through feeling.

As so often with Wagner’s formulation, one could wish that he had expressed himself a little more clearly, at the same time as one sees what he means, and is impressed. He felt the truth of what he wrote here so powerfully that he made it, in slightly adapted form, part of the actual subject-matter of his last drama, Parsifal. And in fact the feeling which the sympathetic spectator or listener has, in the face of Wagner’s works, is remarkably accurately caught by it. They do typically work at an extremely high emotional pitch, which is resolved in the final minutes of the dramas. Therein lies much of their enormous appeal, expressed as succinctly as possible in Wagner’s statement of his purpose just quoted. But the progression of feeling which they induce is also precisely what makes them suspect for many people. For it involves a huge measure of trust in the artist, the more so when he pitches things at so intense a level. As we are swept through his works, mesmerised through the means which Wagner to a unique extent commands, critical distance is made impossible (so the argument goes), and we could be persuaded by him of anything.

It is interesting that this passage from Opera and Drama is quoted by Deryck Cooke, one of Wagner’s most ardent intelligent admirers, at the beginning of his vast, regrettably unfinished study of the Ring, entitled I Saw the World End (the rather strange title is taken from some discarded lines which were at one stage part of Brünnhilde’s peroration in Götterdämmerung). Anyone who writes at length expounding the significance of Wagner’s works has, it would seem, to ignore this claim. Cooke’s position is that it holds good for the dramas apart from the Ring: ‘with the others, we do find that our feeling is set at rest, that nothing remains for the intellect to search for, that our instinctive knowledge of life is enriched, and that we become “knowers through feeling”’, he writes. But he thinks that things are different with the Ring, and that therefore a commentary of great thoroughness is required in order to make its meaning clear. But that suggests, surely, that the Ring is some kind of failure.

It seems strange of Cooke to make this distinction between the other dramas and the Ring. All of Wagner’s works require exegesis, not because they are flawed or opaque, but because even if they do in some way enable or help us to become ‘knowers through feeling’, the ‘synthesising intellect’ still has an enormous amount of work to do, and of a highly profitable and strenuous kind. The question is what it has to get to work on; and the answer is the feelings which the dramas have aroused in us, even if they have, in the closing sequences, been in some sense set to rest. For clearly it is possible for music, with its phenomenal resources of creating harmony and order out of their opposites, to persuade us that a dramatic resolution has been achieved. One of the reasons why there are so few operatic tragedies is that composers have been tempted, and have nearly always succumbed to the temptation, to show that however desperate things get dramatically, it is never beyond the powers of music to rescue them. That makes operatic criticism a very tricky business, since the critic can’t ignore the music, obviously, but has to decide on the exact role which it has been called upon to play.

The easy way out, where Wagner is concerned, is the one which Nietzsche finally took, and Adorno after him, in his polemic In Search of Wagner. Both writers point to the pervasive idiom of Wagner’s music, and ask, rhetorically, whether you think that you can trust a man who employs those means in order to get his message across; as one might point to a politician and ask why someone who meant what he said and had something worth saying should indulge in that particular mode of speech. They have every right, indeed duty, to ask the question, but not to make it into a rhetorical one – the asking of rhetorical questions being itself an activity which needs scrutinising. Wagner is, par excellence, an artist who has designs on us, and who therefore leads us to examine anew the Keatsian view, winning because of the very innocence of its dogmatism, that we should mistrust all such artists. The innocence – one which is shared by both Nietzsche and Adorno, but they go to inordinate lengths to establish their sophistication – is in imagining that there is any art which does not have designs on us, palpable or otherwise. No doubt we want, in the presence of art, to feel a peculiar freedom, and the more so the less we feel it elsewhere. That was Kant’s claim: that the autonomy of the aesthetic artefact has a close relationship to the autonomy of the spectator (auditor, etc.), indeed makes it possible as it is not anywhere else in our lives, where we are ruled either by the laws of Nature, nonprescriptive but nonetheless ineluctable; or the laws of Morality, easily violated but peremptory and absolute (to use George Eliot’s intimidating formulation). But whatever the content of ‘freedom’ in our responses to art, it seems that the more palpable the designs an artist has on us, the freer in one way we are, since there is then no question of our thinking that he is merely presenting us with ‘the facts’ if he is making it perfectly clear what attitude he wants us to adopt to them.

When we are dealing with a mixed art-form, such as opera, not to speak of the Gesamtkunstwerk, a kind of art which combines all the other forms, which is what Wagner wanted his mature works to be, the question evidently becomes more complex still. If we divide opera into action (or plot), text and music, then the crucial issue is the role that music plays. In his most famous dictum, Wagner claimed that in traditional opera music, which should be the means, had become the end, while drama, which should be the end, was merely the means. His revolution in opera, as opposed to all the other revolutions which he hoped to effect, was to be the placing of music and drama in the right order. To establish from first principles what that order was, Wagner was driven to his heroic amount of theorising, much of it unacceptable because it is so vague and groundlessly speculative. But what we can certainly agree with is that however much music is in the service of drama, it has, in the hands of all the operatic composers whose work survives, a capacity to direct our sympathies which none of them has failed to exploit. It may well be that opera is all the more effective when that is not what it appears to be doing, but that is chiefly to say that we admire the cunning of self-concealing enterprise.

It can seem that Wagner refuses to join in the time-honoured procedures of the artist, that he manifests in his dramas the lack of tact which was so striking a feature of his personality in general, and that his reverence for Beethoven is most apparent in his taking over the insistent nature of Beethoven’s music, a source of pain to his most fastidious listeners. We shall have to see about that. But it is an impression which many people have gained from listening, in the first place, to highlights from his works, the usual way, perhaps, of hearing things by him. Which brings me to the topic which someone who hasn’t yet seriously encountered Wagner’s art, but is thinking of doing so, is likely to be preoccupied by.

2 Prejudices and Banalities (#ulink_f3bc367e-c22a-52d5-b45e-b406c00d621e)

What I would like to do now is move immediately to a consideration of key aspects of Wagner’s work, by discussing some of his dramas and the themes with which they are concerned. But at some point I have to deal with an enormous amount of controversy that still rages about many aspects of his life and personality, and which, if one ignores it, is brought up as something which renders pointless any other discussion. Of course one can’t hope to transcend the controversy: Olympian postures in relation to it merely fuel it further. Nor, given the questions around which it revolves, can one hope to settle it. The only course is to wade in and make, as succinctly as possible, what one regards as the crucial points, emerging on the other side in as decorous a state as one can contrive.

It is presumably some evidence of what is taken to be a strikingly direct mode of statement in Wagner’s works which leads people to feel that the alleged facts of his life are relevant to understanding and judging them in a way that doesn’t occur elsewhere in music, music-drama, or literature – and this in the case of a dramatist whose sympathies might be expected to be distributed among his characters. There wouldn’t be a ‘case of Wagner’ if he had not been one of the most significant figures in the development of music and opera. But if he had led a life of sufficient ordinariness for his biography to be a bore, the case of Wagner would be much less insistent and incessant than it is.

A few recent examples, to show the level to which one has to descend if one is not to be felt to be just condescending. In his strikingly intelligent and serious A Guide to Opera Recordings (Oxford University Press, 1987), Ethan Mordden writes: ‘Parsifal is a lie, for Wagner was a sinner: hypocrite, bigot, opportunist, adulterer’ (p. 170). That telling ‘for’ could only have been used on the assumption that Parsifal is meant to be a proclamation of belief, and that if someone doesn’t behave in the way which he is taken to be recommending, he is a hypocrite. There are many disputable remarks in Mordden’s book, but this is the only one that seems to be evidently inane. Only about Wagner would anyone venture to make it.

In The Times of 15 February 1993, Rodney Milnes, one of the most earnest of opera reviewers, wrote apropos of Tristan und Isolde: ‘Nearly six hours spent in the theatre being buttonholed with long-winded and specious justification of the composer’s taste for other people’s wives in general and Mathilde Wesendonck in particular is wearing on one’s patience.’ So that’s what Tristan is! Probably Milnes would claim that he was only high-spiritedly letting off steam, taunting those members of the audience who might be taking the work too seriously: ‘Tristan und Isolde, an obsessively morbid and unhealthy work…’ the paragraph containing the previous quotation begins. But why the rage, why the dragging in of Wagner’s private life (actually a grotesque version of it)?

In The Times of 13 July 1993, another critic, Barry Millington, one of the leading ‘experts’ on Wagner of the present time, acclaimed a production of Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg for revealing ‘the dark underside of the opera’. ‘In short,’ Millington writes, ‘the opera is the artistic counterpart of the ideological crusade launched by Wagner in the 1860s: a crusade to urge Germany to awaken, to expel alien elements and honour the “German spirit”. The characterisation of Beckmesser is demonstrably anti-Semitic.’ The ‘demonstration’ which is supposed to support that adverb is contained in an article by Barry Millington, published in the most self-consciously high-brow of contemporary opera journals, Cambridge Opera Journal. Clearly the tone is a more solemn one than Milnes’s, but that shouldn’t conceal the crass confidence with which Millington presents as fact his own preposterous opinions. To demonstrate their absurdity would be out of place here; I will merely point out that to the extent that the article in the learned journal claims to make its point, it is by the accumulation of a large number of clues which no one has ever picked up on before, and that by its very ingenuity it refutes itself: Wagner was often subtle, but he didn’t write in code. It might have occurred to Millington alias Holmes that Wagner, in the cause of his crusade, should have rendered his message to the German nation somewhat more accessible.

To grasp fully what leads people to write about Wagner in this way – and every reader will agree that there is no other major artist who elicits remarks of this kind, as methodologically absurd as they are deliberately provocative – we shall have to wait until examining some of Wagner’s art in some detail. But we don’t need to wait until then before acknowledging the strangeness of the hostility, its intensity and its reaching for any weapon that comes to hand (minds hardly seem to be involved) to clobber Wagner with. The most obvious feature of all the remarks quoted, and one that pervades anti-Wagnerian polemic, is the simplicity of the transition from features of Wagner’s extra-musical activities to animadversions on his art. One doesn’t need to have been involved in the intricacies of the dispute about the ‘Intentional Fallacy’, the tersest statement of which was ‘the design or intention of the author is neither available nor desirable as a standard for judging the success of a work of literary art’, to feel that the relationship between an artist’s life, including his intentions in producing his art, and his actual artistic productions, must be a matter of some complexity. Yet though this is widely accepted for virtually every other case in the history of art, it is utterly ignored when we come to Wagner. This would be, perhaps, understandable if he had been a villain on a prodigious scale (some people think that he was). But adulterers, hypocrites, opportunists, even anti-Semites, are not all that uncommon in the artistic community or outside it. Wagner never behaved with such extravagant malignity as Beethoven, for example, in relation to his sister-in-law, or so dishonestly as Beethoven to his publishers. But though Beethoven’s biographers tend to deplore his irrational behaviour, amounting sometimes to insanity, they, and other people, never, so far as I know, find that a reason for questioning the greatness of Fidelio or the Missa Solemnis or the Ninth Symphony. And those who are favourably impressed by Peter Shaffer’s portrayal of Mozart in Amadeus tend, like its author, to find an extra frisson in celebrating the achievements of so otherwise comprehensively idiotic a figure as that play depicts, not to feel that they are diminished.

So is it simply that there is something uniquely unattractive about Wagner’s character, which puts him in a category by himself? And what kind of thing is it? As I quoted Hans Keller saying, people do find his consciousness of his own genius distasteful. The reiterated charges about his emotional, libidinal life seem absurd, since he was not promiscuous on a particularly large scale, or as much as many artists, and others, who have been are accorded forgiveness by their virtuous commentators. But there is the impression that his various unattractive facets somehow – no one has said exactly how – add up to, are part of, an integrated character which is, again somehow congruent with his music, or the dramas of which it is a crucial part. It is thought to be, especially by those who have heard little of it, overbearing, noisily emphatic, erotically charged even in the most inappropriate passages, and effusive in a way that leads to suspicions about its sincerity.

But then why not just write it off? When one contemplates the immense annual production of anti-Wagnerian propaganda, the suspicion becomes inescapable that for many listeners his art presents a threat, if not a temptation. Among other things, to admire it seems to be committing oneself to allowing him to take up more emotional space than one artist, or at least one artist who practises his peculiar forms of persuasion, should be allowed to do. A striking moralism comes into play in his case, as it rarely does elsewhere. Perhaps the fundamental anti-Wagnerian argument can be fairly presented in these terms: even though he is writing dramas, Wagner himself is omnipresent in them, in a way that Shakespeare impressively is not in his dramas, or even Racine in his. So the total effect of any of them, at any rate the mature ones, is of coming into contact with a personality all the more powerful for dispersing himself into all his characters. And such is the force of his art that he turns his listeners/spectators into accomplices. Becoming a Wagnerian is, at least incipiently, becoming like Wagner. That was, once again, Nietzsche’s claim.

But why becoming like Wagner, as opposed to becoming like what Wagner presented himself as, granted that one accepts the argument at all? For the difference seems to be immense. The staple of Wagnerian drama, the whole idiom, is one of nobility.

All the worse, the reply comes back; by a variety of means Wagner conveys the impression of an earnest orator. But what he really is is a brilliant demagogue, whose rhetoric is so resourceful that we naturally find it suspect. Anyone who genuinely believes what he says – this is our prejudice, unexamined and even sacrosanct – can communicate it without going into constant overdrive. Nietzsche, the incomparable and tireless exposer of our prejudices in all fields, subscribed uncritically to this one. Contrasting Mozart and Wagner, he cleverly takes the music that Mozart gives the Commendatore when he appears in the Supper Scene of Don Giovanni, a passage of most atypical violence and emphasis, and writes: ‘Apparently you think that all music is like the music of the “Stone Guest” – all music must leap out of the wall and shake the listener to his very intestines. Only then you consider music “effective”. But on whom are such effects achieved? On those whom a noble artist should never impress: on the mass, on the immature, on the blasé, on the sick, on the idiots, on Wagnerians!’ (Nietzsche contra Wagner). Once more, as so often with Nietzsche’s sweeping charges, this contains illuminating truth as well as outrageously unfair falsehood. But it does rely on the view that the genuineness of a conviction can be assessed by its mode of communication, and that the extreme nature of Wagner’s art, ‘espressivo at all costs’, as Nietzsche puts it elsewhere, betrays an uncertainty. Either that, or it hides something. Wagner’s surface of nobility conceals his underlying insecurity and egoism, not to mention his pusillanimity.

It is almost impossible to find out whether these things would be said about Wagner if his well-advertised personality defects weren’t known about, because the advertisement has been so successful that no one has escaped hearing about it. Even people who take no interest in music can retail odd facts about Wagner. So I shall now do two things, for the rest of this chapter: first, consider some aspects of Wagner’s life and character. Secondly, see to what extent his alleged views and vices are thought to be evident, in more or less indirect ways, in his work. There is, to begin with, his overbearing personality and strength of will, remarked on by everyone who knew him, and one of the most powerful sources of his fascination for them. This urge to dominate, combined with a charm which he could exercise whenever he felt inclined, and which he is claimed to have used to manipulate people with the sole aim of furthering his own ends, was realised by many of those in thrall to him, and even accounted for their willingness to serve him until, as with Nietzsche, they revolted against such tyranny. But some who had problems reconciling their own need to create with moving in Wagner’s orbit found that it was, in the end, possible to do both, and a risk worth taking. Peter Cornelius, composer of the winning comic opera The Barber of Baghdad for instance, broke with Wagner and then went back to him. He wrote to his future wife: ‘I am quite determined to stick to him steadfastly, to go with him through thick and thin, partisan to the last ditch. When I see how others, like Bülow, Liszt, Berlioz, Tausig, Damrosch treat me, ignore me, forget me, and how he, the moment I show him even a hint of my heart, is always ready to give me his full friendship, then I tell myself that it is Fate that has brought us together.’

Next, there is Wagner’s financial history, a spectacular affair, certainly. From an early age he was in debt, chronically so, partly because he rarely had a settled source of income, partly because he never ceased to indulge his love of luxury, one of the traits which earned him most ridicule as well as disapproval from his contemporaries, as one can see in many cartoons. Anyone who lent him money, and most of the people who came into contact with him did, was foolish to expect that they would ever see it again.

His treatment of the women who played so large and indispensable a part in his life is also a subject of self-righteous recrimination. Once more, it may not be the sheer number that were involved, but rather the ruthlessness with which, if they had more than a one-night stand with him, they tended to get treated. This is supposedly true of his first wife, Minna, to the most extreme degree, but of at least half a dozen others too.

Last, most serious and now most often used as conclusive evidence against him, there is his racism, of which the two correlative elements were an ever more virulent anti-Semitism and an insistence on the necessity of the purity of Aryan blood if mankind was not to degenerate (a concept that was becoming very fashionable towards the end of Wagner’s life) to a point where it was irredeemable.

The strength of will and ruthlessness in pursuit of his aims is something we may freely grant. The question, insofar as it concerns a moral judgement on Wagner’s character, is whether it was exercised only for his own gratification, or whether it was of the kind which anyone with a serious and radical programme of reform of what they regard as vitally important is bound to employ. Whatever one thinks of Wagner’s attitudes, artistic and socio-political, he was an idealist. He was by no means bent only on the furtherance of his own fame, glory, and so on. He was, to a remarkable degree for a revolutionary artist, a hero-worshipper of his greatest predecessors. During the period of his life when he did have one job, as director of Dresden’s musical life, from 1843 to 1849, he raised standards of musical, especially operatic, performance and production to a level which had not previously been envisaged. In order to get for Gluck the recognition which Wagner felt he deserved and lacked then (as to some extent now), he not only gave what seem to have been exemplary performances of his works, but in the case of Iphigénie en Aulide, which he felt was flawed in ways that obscured its merits, he extensively rewrote it. A misconceived enterprise, it might be thought. But it was carried through without thought of his own interests, and at the expense of his own creative work, for which he had far too little time, since his administration of the opera house was so conscientious. These things need bearing in mind. For what we routinely find in scholarly works is this kind of claim: ‘Wagner’s monomania is well known. In his whole life there seem to have been hardly any occasions when he was capable of disinterested co-operation’ (M. S. Silk and J. P. Stern: Nietzsche on Tragedy, p. 216). The authors proceed to cite a rare exception; but note the shape of the argument. They don’t need to give any evidence for Wagner’s monomania, since it is ‘well known’. So the counter-example must be an exception. It is in that way that myths become history.

What galls people even more than Wagner’s idealism is that he was a practical idealist. He succeeded in making real what his contemporaries regarded as ludicrous pipe-dreams. But many of them were in the interests not only of great art, with which his only connection was passionate devotion, but in the interests of those who were performing it. He had a lifelong concern with the welfare of the musicians with whom he performed, and who idolised him. He drew up detailed and carefully worked-out plans for the betterment of the Dresden orchestra, and did a great deal to put the careers of the musicians in Zurich, when he was exiled there, on a secure financial footing. He believed, from extensive experience, that they were unlikely otherwise to give of their best, but there is no reason to think that that was his only or primary motive; unless one is determined to see him as ‘an absolute shit’ and ‘a very bad hat indeed’, to invoke two of W. H. Auden’s judgements on his character.

Wagner’s preparedness to be as hard on other people, in the fulfilment of what he saw as his mission, as he invariably was on himself, is undeniable. And it is easy to slide from that to his ‘using’ people. The prize example here is King Ludwig II, and it is worth looking at his relationship with Wagner in a bit of detail because it is so common to regard the King as the pathetic but rich host, Wagner as the impoverished but triumphant parasite. In the most famous single episode of his life, Wagner, in 1864, was in hiding from his creditors, at the end of his financial and all other tethers, when the eighteen-year-old Crown Prince came to the Bavarian throne, and as his first act sent his cabinet secretary in search of the composer whom he had idolised since early adolescence. Having finally run Wagner to ground, the secretary Pfistermeister conveyed his royal master’s greetings, Wagner went off to Munich the next day, and Ludwig promised to settle all his debts, set him up in the comfort he needed for completing the Ring, and ensure its production. A Platonic honeymoon ensued, but was short-lived. The populace of Munich was scandalised by Wagner’s behaviour, he made enemies in the cabinet by attempting to influence Ludwig’s political opinions, and later on he lied to him about whether he was having an affair with Cosima, the wife of Hans von Bülow, the conductor who was tirelessly preparing the first performance of Tristan und Isolde. Their relationship continued until Wagner’s death, but Ludwig was, for all his passion for Wagner’s art (more its scenic than its musical aspects), sadly disillusioned with its creator, whom he once included in a denunciation of ‘the theatre rabble’.

It is, in many respects, a painful story. But the truth is that Ludwig, in his lonely misery, found his chief consolation in watching Wagner’s dramas. He wanted them finished and performed for himself alone – his preferred way of seeing them was in a theatre in which he constituted the sole audience. He was one of the first of the breed of people who have found Wagner’s dramas superior to life, and in straightforward competition with it, and was unusual among them only in that he had the means at his disposal to build himself a Venus Grotto, a Hunding’s Hut (both in the grounds of his pleasure palace Lindenhof), and to spend a large part of the time which should have been occupied in affairs of state pretending to be Lohengrin. There is no single piece of evidence that he wanted ‘to save Wagner for the world’, as he put it on hearing of Wagner’s death, to which his immediate reaction was, ‘Oh! I’m sorry, but then again not really. Only recently he caused me trouble over Parsifal.’ And as for the expense which Wagner caused him – and it does seem very unlikely that without Ludwig’s aid Wagner’s later works could have been written – the decorations for Ludwig’s bedroom in Herrenchiemsee, his recreation of Versailles, cost considerably more than all the money and gifts in kind that he gave Wagner over nineteen years; and his wedding coach, never used, three times as much as he gave Wagner. The treatment he received from the composer was compounded of genuine gratitude, warm affection and concern at the start, and exploitation in the service of his art.

Admittedly Wagner wrote in a letter to Liszt: ‘If I am obliged to plunge once more into the waves of an artist’s imagination in order to find satisfaction in an imaginary world, I must at least help out my imagination and find means of encouraging my imaginative faculties. So I cannot live like a dog, I cannot sleep on straw and drink common gin: mine is an intensely irritable, acute and hugely voracious, yet uncommonly tender and delicate sensuality which, one way or another, must be flattered if I am to accomplish the cruelly difficult task of creating in my mind a non-existent world.’ That does strike me as candid. If, on the basis of it, hostile judgement of Wagner is in place, he would even so not be worse than many people who escape the criticism that is heaped on him because he told the truth and was incessantly in the limelight; quite apart from the reputation he has earned from producing his works under the conditions, some of the time, which he tells Liszt he craves. Quite a lot of the time he managed to create them despite poverty and discomfort, but I don’t see that he should have had to endure more of that than he did. All told, I’m inclined to feel that Wagner’s capacity for making writers on him, many of them securely established in academic jobs, reveal their priggish and disapproving lack of imagination is his most vexing feature.

However, on to Wagner and sex. After some youthful gallivanting of a commonplace kind, he married a woman who was in no respect suitable for him, and their life together was unhappy for the most part. Very shortly after the marriage his wife Minna ran away with another man, twice. Her sexual history had begun distressingly, with a seduction which led to the birth of a daughter, Nathalie, whom Minna always passed off as her sister, and thanks to Wagner’s loyalty, the secret was not discovered during her lifetime. Minna was a great admirer of Wagner’s worst work, Rienzi, and was unable to understand why he felt the need to write operas vastly different from it, which were less successful at the box office and led to lengthy periods of near-destitution. That they didn’t give up the effort to live together until decades of misery had passed is a mystery. Under the circumstances, Wagner’s intermittent passions – he always needed a muse – are in no wise surprising. And what was certainly the grand passion of his life, for Mathilde Wesendonck, though it caused all the parties concerned great pain, was hardly anyone’s fault. Its connections with Tristan – was Wagner in love with Mathilde because he was writing Tristan, was it the other way round, or a mixture of the two? – can never be sorted out, if only for the reason that this is one of those matters in which there is no such thing as the truth.

His second marriage was as mutually fulfilling as his first was frustrating. Cosima, illegitimate daughter of Liszt, had married early in her first attempt at self-sacrifice to a man of genius, Hans von Bülow. Unfortunately he was tormented by not being genius enough, and their marriage was, in its way, as unhappy as Wagner’s first. Since for Cosima, a woman of extraordinary gifts, it was inconceivable that she should not play the part of a George Eliot heroine to someone who needed her, it was inevitable that frequent contact with Wagner should lead to passion. As so often in such situations, the idea was that in concealing their relationship from Bülow they would spare his feelings, though of course that is never possible. Cosima’s guilt over the deception pervades her diaries, written after everything was in the open. She and Wagner would have been fools to refuse to enter into what became one of the most famously productive partnerships in history, Cosima giving him every kind of support, except financial, during the last eighteen years of his life when he was bearing crushing burdens of responsibility, creative and otherwise, and his health was in decline. Wagner had one last fling, with Judith Gauthier, in the period of the first Bayreuth Festival, an affair of which the remarkable Cosima was aware and which she sanctioned, knowing that it would not survive for long.

So if Wagner had ‘a passion for other men’s wives’, as the familiar account goes, that may be due to the fact that most women he met were married, a problem he wouldn’t encounter now. He certainly didn’t welcome the complications that they involved. Once more, I find it hard to understand the fuss.

But it is all too easy to understand the fuss about Wagner’s anti-Semitism, which was virulent even for the time, and moved from what seems to have been a mildly paranoiac state to one of obsession. That he was in the company of many of the most distinguished men of the day makes things no better, though racial theories are not evidently absurd, indeed the reverse. Wagner suffered from a lifelong need to locate the evils of life and society in one area, and it is not surprising that, in carrying through this boring programme, he should have selected the Jews. He was no more anti-Semitic than, say, Luther or Kant or Marx, but he was nearer in time, except for Marx, to the vilest of all racially-based political programmes and its enactment. And since the Nazis were so violently anti-Bolshevik, that has let Marx off the hook.

To say that many of Wagner’s best friends were Jews may sound like a weary defence, but it is not meant as a defence at all, merely as a sign that his attitudes towards Jews were inconsistent. The crucial question is whether his anti-Semitism invades his works. If it does, then they are even more controversial than they have always seemed, and in a way that is bound to take them finally beyond controversy into repugnance – except for those who thrill to the unsavoury. Though it is a crucial question, I believe it can be rapidly answered, as I indicated at the beginning of the chapter in mentioning Millington. If they are in any respect anti-Semitic, then that element in them is coded. They are, that is, to be sharply distinguished from The Merchant of Venice. But Wagner was the most explicit of men, both in the whole of his tactless life and in what is often thought to be his no less tactless art. Where are the Jews in his works, and how are we to recognise them? The chief focus, until recently, for Jew-spotting has been the Ring, since it is allegedly about the evil of possessions. That leads many commentators to claim that Alberich is a Jew, and even more obviously Mime. But if they are, so is the whole race of the Nibelungs, and they are depicted as pathetically downtrodden workers, the very image of the misery for which Jewish capitalism is responsible. Apart from which, Alberich is not as simple a villain in the Ring as casual acquaintance with it might lead one to think. He exists in intimate relationship to Wotan, who is referred to as ‘Licht-Alberich’ (Light-Alberich). The plot of the Ring simply can’t be worked out in racial terms. And the fact that Wagner devoted many pages in his letters to expounding its meaning, and that Cosima’s Diaries are full of references to it, without the question of its Jewish ‘sub-text’ ever cropping up, surely is decisive.

More recently – and it is interesting that it is after the Nazi period that most of this discussion has taken place, not during it, even on the part of the Nazis themselves, who would have been keenest on Jew-spotting – it has been alleged that some of Wagner’s other major villains are Jewish, for instance Beckmesser in Die Meistersinger and Klingsor in Parsifal. Once more, why did Wagner make the point so obscurely that we have had to wait more than a century for these ‘discoveries’ to be made? The very elaborateness, for all its fatuities, of Millington’s argument for Beckmesser’s Jewishness is a refutation of the claim.

But how, one might wonder, could anyone be as obsessively anti-Semitic as Wagner without its entering his works? One might well wonder, but the gulf between the life and opinions of an artist and his creative work has surely been sufficiently established by now for us to admit that such extraordinary discrepancies are more frequent than the congruities we obstinately continue to expect. If we don’t accept that, we are going to lapse into the circularity of claiming that Wagner thought Jews were bad, and so the villains in his works are Jewish; and you can tell how much he disliked Jews from the ghastliness of the bad characters in his works. That is the level of sophistication at which these arguments operate.

That was originally all I was going to say on the subject, since I have already had to repeat myself in order to appear to take the issue seriously. But of course it has to be taken seriously, in some sense. Since I wrote this chapter there have been two books on the subject in English alone, and in a series of programmes on Channel 4 on English television, called ‘Wagnermania’, it was clear that Wagner’s anti-Semitism is the one aspect of him which the series’ sponsors felt guaranteed an audience. Not that anything new is forthcoming. In fact, the presenters of the argument that Wagner’s works are insidiously anti-Semitic, including the ubiquitous Millington, were at pains to point out that the ‘fact’ might all too easily be overlooked by audiences, unless they were instructed in what Wagner wrote in his pamphlets, and said to Cosima. The authors of the two books have to adopt a similar line. One might feel, under the circumstances, that it would be better if they kept the information to themselves: not because it damages Wagner, but because it is unclear how informing people that Alberich is ‘really’ a Jew is giving them anything which serves any purpose in understanding the Ring. Supposing that Wagner intended that he should be seen in that way. In the first place, it is only within a certain framework that calling someone a Jew has any significance. It isn’t as if the rest of the characters in the Ring are threatened Aryans, or uncorrupted until Alberich takes his decisive action. In the second place, the advocates of the final solution to the Wagner problem, as one might call them, are all arguing on the basis of Wagner’s alleged influence on the Nazis. It might be thought scandalous to say ‘alleged’; but only Hitler was an enthusiastic Wagnerian, insisting that the functionaries of the Third Reich attend performances of the dramas which bored them stiff. And if Hitler had taken the dramas seriously, he would hardly have felt encouraged to pursue his policies, since Wagner shows the futility of political action in dealing with the world’s evils. He might have noticed, too, that the only major character in the Ring who survives it is Alberich, and been disheartened.

That there are some similarities between the Nazis’ proclaimed ideology and some of the conclusions which Wagner may be suggesting in his dramas – though as we are about to discover, that is no simple matter – I am not disposed to deny. But to attempt to draw any systematic conclusions from that is futile, especially if it is a matter of blaming Wagner for their outlandish views. Oddly, it is widely agreed that there neither was, nor could have been, any great Nazi art. But the people who say that are prepared, nonetheless, to say that there was – avant la lettre.

Basta! No one ever changes sides on these issues. I just hope that I have got in first for people who have not yet taken sides, and provided them with some rudimentary equipment.

3 Getting under Way (#ulink_8a4df6f6-97b2-5cac-a214-dde2dac9ef0f)

Having in the first chapter floated a fair number of ideas, and in the second sunk, I hope, several of the most popular misconceptions about Wagner, I can now move on to a discussion of what is in the first place important about him: his musical works, which I shall designate as dramas, music-dramas or operas indifferently. His first artistic impulses were theatrical, music entering at a slightly later stage. Enormously excited as a boy by the sheer atmosphere of the theatre, and then finding the music of, above all, Beethoven deeply moving, it was clear that he would, if he was to be creative, combine thrills and emotions in the most popular contemporary form, that of opera. Contrary to the impression he sometimes gives in his many autobiographical retrospectives, Wagner received a thorough training in the elements of composition, through assiduous study of the masters of counterpoint. When he came, at the age of twenty, to compose his first opera Die Feen (‘The Fairies’), the chief constraints on what he wrote were those of having no very urgent need to communicate anything. It is very rare in Wagner that we feel a gap between his aspirations and his capacities – but all he aspired to at this stage was to be an opera-composer, with no particular subjects or themes in mind. As an ardent admirer of E. T. A. Hoffmann, and in love with the atmosphere of early German Romanticism, he sedulously devoted himself to producing a work which caught the spirit of Weber as fully as possible. The opening bars of the Overture to Die Feen, and much else besides in the work, might have come from Weber working at less than full pressure.

The result is a work of considerable charm, not much originality, and a pervasive uncertainty about how seriously it wants to be taken. One of Wagner’s most important statements of his development, A Communication to my Friends, written nineteen years later in 1851, makes a good deal of the fact that some of the central themes of his later works are adumbrated in Die Feen. Up to a point that is true, but as always the question is at what level they are dealt with, and the level of Die Feen is nothing to get worked up about; though it is certainly as enjoyable an opera as many that are revived these days to cries of the thrills of rediscovery. It is rather a long work for its slender substance, but it is at least as well worth hearing as most of Mozart’s or Verdi’s early operas, to take a couple of cases of severe contemporary overvaluation.

Despite its irrelevance for any serious consideration of Wagner, Die Feen is a plausible starting-point for a composer whose preoccupations were later to be with the supernatural, with the centrality of love as leading towards some mode of redemption, and with the expression of his dramatic themes in a German musical idiom. His next opera, Das Liebesverbot (‘The Ban on Love’), based loosely on Measure for Measure, can only be seen as an act of fairly gross infidelity to his muse. True, there are some passages that give a foretaste of Wagner’s later works more strongly than anything in Die Feen, and the tumescent motif which appears in the Overture, and in the scene between Friedrich (the Angelo figure) and Isabella, is strikingly characteristic. But the whole ambience of the work, its celebration of uninhibited hedonism, is utterly remote from anything that one thinks of as Wagnerian. In fact Wagner was going through a rebellious period, in which ‘German’ signified for him what it vulgarly does for many people – heaviness, soul-searching, and in musical terms a lack of interest in sustained singable melody. He was infatuated with the music of Bellini, the supreme bel canto composer, and a love-worthy object. But although Wagner never lost his affection for Bellini’s work. he soon came to realise that he was not destined for that path – or rather, that for all its appeal it wouldn’t serve his purposes. And in fact he was only able to use Bellini by misunderstanding him. He even went so far as to write an alternative aria for Oroveso, to be inserted in Norma, Bellini’s masterpiece. Listening to that aria one is amazed that Wagner thought he had captured the flavour of Bellini.

In Das Liebesverbot, which is once more an enjoyable opera, though again somewhat overlong, it is possible to feel that the young Wagner was putting up a misguided battle with his destiny. It manifests, if not with consummate skill, at least with gusto, many of the things which he was to spend the rest of his life fighting against with single-minded dedication. The theme of the ban on love itself he revisited in one work after another, but in his mature output the various ways in which the ban is brought into operation are seen as deep elements of human nature, as the concept of love itself becomes something of increasingly daunting complexity. But in Das Liebesverbot the figure of Friedrich, who imposes the ban, is a one-dimensional caricature, and a hypocrite to boot. He merely provides what suspense there is in the plot, while Wagner is mainly keen to express a mood of carnival and enthusiastic youthful rebelliousness. No comparison with the Shakespeare play would have any point: Shakespeare produced a deep, and in my view deeply flawed, work. Wagner produced something which doesn’t reach a level where serious criticism is appropriate. He was, as it were, shopping around. His first opera was an attempt in the German mode, reflecting what Wagner took to be his concerns; his second was one of those trips across the Alps which Goethe seems to have made obligatory for Germans at some stage of their career.

With almost too handy comprehensiveness, Wagner’s next effort, Rienzi, the last of what have been widely and rightly agreed to be his juvenilia, was an emulation of grand French opera. Though it is artistically the least satisfactory of these three works, it provides more interesting food for thought than do the first two. Wagner tried to produce a grand historical tragedy, basing it on the novel by Bulwer Lytton. On its own terms – or rather those of Meyerbeer, who had set the fashion for this kind of oversized period drama, with its compulsory ballets, spectacular scenery and vast cataclysms – it is successful to a degree that makes one fear for Wagner’s integrity at this stage. Perhaps it is fairer to say that since he still lacked an artistic identity, there was nothing to be single-minded about. And yet the beginning of the Overture, the first piece of Wagner’s music to have retained its place in the repertoire, is original, moving and unmistakable. It starts with a long-held trumpet note, evocative both of majesty and suspense, and then moves into the first great arch-Wagnerian melody, richly scored for strings. That melody, which provides Rienzi with the material for his Prayer at the beginning of Act V, has a nobility which almost everything else in the work betrays, including most of the rest of the Overture, a blowsy piece which, once it moves into its allegro stride, skirts vulgarity with a Verdian brio, though it is much more heavily scored than anything by the Italian master.

This theme, which can’t be called a motif, since it is too fully-formed and monolithic to be plastic enough for that purpose, clearly indicates the hero’s greatness of soul. But in the work itself Rienzi has to become a figure who has been forced to sink to the level of the intriguers around him, so that there is a disjunction between his portrayal in the opening section of the Overture and everything that comes later, apart from the recapitulatory prayer. The only way that Wagner can resolve the action is through a suitably apocalyptic conflagration, as the Capitol is ignited by the angry crowd and Rienzi is immolated along with his visions. Once more, if one were so inclined – many commentators are – one could trace connections between elements in Rienzi and the later works, including, very obviously, the conflagration at the end of the Ring. But such comparisons are more likely to subtract from the sublimity of Götterdämmerung than to add to the stature of Rienzi. That Wagner was fascinated by certain types, and by what might happen to them, is clear enough. But it is merely confused to think that later versions are nothing more than the earlier ones with sophisticated and far greater music to lend them glamour and plausibility. In the case of many of the greatest artists who can, in a sensible way, be said to have subjects, they show what those subjects are going to be from their earliest works. But what makes them great is their capacity for working with certain terms and endlessly exploring and deepening them, until the connections with what they started out from are better disregarded. Otherwise we get nothing more than an example of the ‘fallacy of origins’, by which the developed form of something is alleged to be no more than its elementary form cosmeticised.

Unfortunately this tendency is especially pronounced with Wagner’s critics, and all the more so since it was attending a performance of Rienzi in Linz which set Hitler, so he often claimed, his goal of absolute power. It may have done, though if he fancied himself as a reincarnation of Rienzi he must have paid scant attention to the action. Perhaps this is one thing for which Hitler can be forgiven, since Rienzi is written in an idiom which discourages concentration. With its spectacle and its elaborate diversions, it was the ideal work for those who went to the opera for ‘effects without causes’ – Wagner’s cruel and famous characterisation of Meyerbeer’s operas, which also applies in large part to Rienzi. In fact one wishes that the opening weren’t so arresting; it raises expectations and suggests a degree of seriousness which are willingly granted. But when they aren’t fulfilled, what may happen is that instead of spending five hours being disappointed, one takes the actuality of the work at a higher value than it deserves, lapsing again into the mistake of thinking there are such things as serious subjects, as opposed to serious treatments of them.

All of Wagner’s three early operas are on a virtually unprecedented scale, at any rate in the history of German opera. He indulged himself in them, letting an impressively far-ranging imagination have its head, at the same time that he was developing his capacity for thinking in long time-scales. Their organisation is rudimentary, but they must have given him confidence in his ability not to let things simply get out of hand. Prentice-work though they are, and worth only occasional airings, they would have established him as a composer of unusual ambitions. But the work which, even if Wagner had never written another, would have remained permanently among the great operas, was his next and most evidently concise drama, and the one in which, at one bound, he found himself – by no means all of himself, but what he did find was wholly genuine and strikingly deep. There may be no other example of a composer so suddenly moving from competence in various idioms of his day to commanding mastery which was partly rooted in tradition, but equally impressive for its necessary departures from it.

The famous opening of Der fliegende Holländer has the hallmarks of all Wagner’s openings from now on: it compels attention, and lets one know instantly what the matter in hand is. Viewed with hindsight, it achieves other ends too. It sounds not only as if Wagner is making a declaration of having found his real self as a composer, but is also showing how he relates to the most admired figures and works in the tradition from which he emerges. For the raging first pages are in D minor, the demonic key of Mozart and Beethoven. Don Giovanni opens in it, and equally cataclysmically. No other operatic overture before Holländer begins so arrestingly, and with music that is part of the fabric of the main action. And Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, a talismanic work for Wagner, and one which he had made a piano arrangement of when he was seventeen, has given nineteenth-century music its definitive D minor statement. Though Beethoven begins almost inaudibly, while Wagner’s Overture rages, they are both elemental, and both use the same material and some of the same devices. Wagner, as always, has his roots in the physical, even though his ultimate intentions are metaphysical; Beethoven evokes a primeval chaos which has no truck with physicality. It would be pointless to press the similarities, but if they were not conscious, that is all the more striking. At any rate, the demands Wagner is going to make on us are clear, and they are immense.

But it is not the Overture that I want to dwell on, rather the drama it portends: for, quite apart from the elemental sweep of Holländer, it is a simple, but certainly a serious treatment of a subject which is at the top of Wagner’s agenda throughout the whole oeuvre, and so, besides its intrinsic compellingness, it is a valuable way into his world, as the three works which precede it are not.

The story is familiar. The Flying Dutchman, whose story Wagner took from Heine, but without the irony – Wagner is the least ironic of artists, at least within his individual works: the ironies exist in their relationship to one another – is, in crude outline, the prototype of the Wagnerian protagonist: someone who has done something so terrible that he has to spend the rest of his existence looking for salvation, or redemption, which comes only through the agency of another human being, even when, as in Wagner’s first three and last dramas, there is a certain amount of theological background (usually vague and non-specific). Though it is characteristic of Wagner’s central figures that they have committed a crime – in the Dutchman’s case, an oath that he would round the Cape at any cost, for which Satan doomed him to eternal voyaging; in Tannhäuser’s that of sojourning with Venus; in Wotan’s that of making a bargain which he has no intention of keeping – it seems that really Wagner was a Schopenhauerian from the start. He only read Schopenhauer in 1854, instantly becoming a disciple.

Schopenhauer claims that living itself is the original sin. That Wagner always held a position which amounts to that comes out in the fact that the ‘redeemers’ in his works long to redeem just as much as the sinners long to be redeemed. Hence it is entirely appropriate, and could well have been a planned effect, unquestionably casting light back over a lifetime’s work, that the final words of Parsifal, intoned by the chorus, are ‘Erlösung dem Erlöser’ (‘Redemption to the redeemer’). Taken by themselves, or just in the context of Parsifal, they are a riddle. But it may not be too difficult to solve it if one surveys the series of characters, often though not always female, who do the redeeming. In Der fliegende Holländer Senta needs the Dutchman quite as badly as he needs her. Her life is without a genuine purpose, it only has a visionary one until he appears on the scene. The various ways in which the sinner/redeemer relationship is worked through is among the great fascinating topics for meditating on Wagner’s works – and one that, in the notoriously vast ‘literature’ on them, is weirdly neglected.

So the Dutchman himself, given a teasing chance every seven years of setting foot on land to find a woman who will sacrifice herself for him, begins the Duet with Senta, which is the heart of the work, with an unaccompanied solo which is more groan than song, and more interiorised recitative than melody. But it does move, gradually, into song, quietly punctuated by the orchestra, as he feels the faintest stirrings of hope, exhaustion hardly daring to give place to a new attempt at salvation. Then, to tense tremolandi from the strings, he moves into a statement of what he feels, which is expressed by a slowly rising melodic line and then a declamatory mode which hovers between song and enhanced speech. The words:

Die düstre Glut, die hier ich fühle brennen,

Sollt’ ich Unseliger die Liebe nennen?

Ach nein! Die Sehnsucht ist es nach dem Heil,

Würd’ es durch solchen Engel mir zuteil!

(The sombre glow that I feel burning here,

Should I, wretched one, call it love?

Ah no! It is the longing for salvation,

might it come to me through such an angel!)

In his justly famous essay ‘Sorrows and Grandeur of Richard Wagner’, Thomas Mann quotes these lines and rightly comments, ‘never before had such complex thoughts, such convoluted emotions been sung or put into singable form’. And he adds, ‘What a penetrating insight into the complex depths of an emotion!’ (Thomas Mann Pro and Contra Wagner, p. 97). But in his account of what it is that the Dutchman is discovering himself to be feeling, Mann seems to me to go astray. For he takes it that the Dutchman is in love with Senta, whereas it is a case of his mis-identifying, and then correctly re-identifying, a feeling. Just as Wagner is, according to Nietzsche’s sneer, always thinking about redemption, so he is always meditating on love. And since the soaring last melody to be heard in the Ring, often taken to be its final ‘message’, has routinely been miscalled ‘Redemption through Love’ by the commentators – an error which Wagner himself corrected, via Cosima – it is easy to conclude that his preoccupation is, if not always, then very often with how love might redeem.

But that is to assume that Wagner has a fixed idea of what love and redemption are, and is concerned with the mechanism by which the former effects the latter. Whereas his works constitute, along with a great deal else, a sustained investigation, often amounting to downright critique, of what love may be, and of what it is we seek when we seek redemption. He inherited an extremely well-worn vocabulary, which embodies the conflicting valuations of two millennia of Western civilisation; and thus he found himself in a profound predicament. Either, because his views were so radical and disruptive, he could coin a new vocabulary, but one which we wouldn’t understand, or would rapidly assimilate to the old one. Or he could use the familiar terms, with all their ambiguities and conflicting forces, and see how they could be put to new but indispensable work, thanks partly to the dramas in which they are saliently employed, and partly to the effects of the music, itself an integral part of the drama.