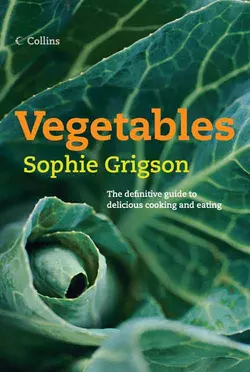

Vegetables

Vegetables

Sophie Grigson

A definitive guide to cooking with vegetables, with essential information on buying, preparing and cooking the vast range now available, from one of the most trusted and knowledgeable cookery writers working today.

With more access to quality vegetables than ever before through organic boxes, farmers’ markets and a greater range in supermarkets, more and more of us are moving vegetables centre-stage in our cooking. Sophie Grigson shows that whether we eat fish and meat, or are a vegetarian, vegetables are no longer just an accompaniment.

Organised according to vegetable type, Vegetables is packed with information and personal anecdotes from Sophie – from her tips on how to buy Jerusalem artichokes to her passion for hard–to–find chervil root – together with advice on how to buy, prepare and cook each type of vegetable.

A range of recipes showcase each particular vegetable, from Wild Garlic and New Potato Risotto to Japanese Cucumber Salad to Crisp Slow-Roast Duck with Turnips. Recipes encompass the familiar as well as the more innovative, with both vegetarian, meat and fish dishes fully represented, ranging from soups and starters to full-blown main courses. This definitive book is a great read as well as a recipe source book that is deserving of a place on every cook’s shelf.

Includes:

ROOTS – from Jerusalem artichokes to yams, including potatoes and carrots

SHOOTS AND STEMS – from asparagus to fennel

FRUIT – from aubergine to tomatoes

SQUASHES – from cucumber to winter squashes

PEAS AND PODS – from bean sprouts to peas

ONION FAMILY – from leeks to onions

FLOWERS AND BRASSICAS – from globe artichokes to cauliflower

GREEN AND LEAFY – from pak choi to spring greens

SALAD LEAVES – from watercress to purslane

Vegetables

Sophie Grigson

For Florrie and Sid, of course

Table of Contents

Cover Page (#u8a0bbc2b-02a4-566a-a569-8a77ad9b8450)

Title Page (#u5044a4fd-29e6-5a07-8f72-61ea6d5b25dc)

Dedication (#uf32c1092-3836-54bb-9de4-cbc51fe52056)

Introduction (#u13083a4a-a536-53e7-bb79-2184c0e97a24)

Author’s acknowledgements (#u31787a4c-ad07-5c20-a6de-f5fff6408f93)

Roots (#u8acfb403-db96-5f2e-8a67-0d98a6306f45)

Beetroot (#u7227fc2a-5a3c-5ad1-a6bf-4ec71e353379)

Carrots (#ua17f3247-21c5-5a3a-ab49-5338e2b7f86e)

Celeriac (#u9538ff64-9886-5cfd-b46c-00b5a962ceb1)

Chervil root (#uf5b072b1-4429-579d-96dc-9d3bc02d6bc3)

Hamburg parsley (#udd745244-c291-5886-9637-15125fc46847)

Jerusalem artichokes (#u39a25d2d-4bdf-5154-96ad-41f2b6353976)

Jicama (#ua1103dab-6707-524f-88d2-cb40ff9e8350)

Kumara (#ufe2422bb-f3ec-572e-be91-f8194861a194)

Oca (#u69f8bb47-12a1-5180-92c8-bf101ecf3386)

Parsnips (#u2614fbcf-cb76-5f9f-a267-b3f7d316bbe0)

Potatoes (#u0246b581-6b62-5bf9-b4db-b1d0f931298a)

Radishes (#u6a6b7c89-dd5a-5276-829a-eb00557105db)

Salsify and Scorzonera (#ubc25c70e-aae5-5835-bbea-853c2bc496d8)

Swede (#u886b6589-913f-599f-9e14-a7f8b7f15bef)

Sweet potatoes (#uffa6bc30-3a43-53bd-8505-b84c853610a2)

Turnips (#u6e093654-63e5-5971-b8a4-a16049d1ee3a)

Yams (#litres_trial_promo)

Shoots and stems (#litres_trial_promo)

Asparagus Beansprouts Cardoons Celery Fennel Globe artichokes Kohlrabi Samphire Wild asparagus (#litres_trial_promo)

Beansprouts (#litres_trial_promo)

Cardoons (#litres_trial_promo)

Celery (#litres_trial_promo)

Fennel (#litres_trial_promo)

Globe artichokes (#litres_trial_promo)

Kohlrabi (#litres_trial_promo)

Samphire (#litres_trial_promo)

Wild asparagus (#litres_trial_promo)

Fruits (#litres_trial_promo)

Aubergine (#litres_trial_promo)

Avocado (#litres_trial_promo)

Bell peppers (#litres_trial_promo)

Okra (#litres_trial_promo)

Tomatoes (#litres_trial_promo)

Squashes (#litres_trial_promo)

Courgettes (#litres_trial_promo)

Cucumbers (#litres_trial_promo)

Marrows (#litres_trial_promo)

Summer squashes (#litres_trial_promo)

Winter squashes (#litres_trial_promo)

Pods and seeds (#litres_trial_promo)

Broad beans (#litres_trial_promo)

Edamame (#litres_trial_promo)

Green beans and wax beans (#litres_trial_promo)

Mangetouts and sugarsnaps (#litres_trial_promo)

Peas and pea shoots (#litres_trial_promo)

Runner beans (#litres_trial_promo)

Shelling beans (borlotti, flageolet and cannellini) (#litres_trial_promo)

Sweetcorn (#litres_trial_promo)

Onion family (#litres_trial_promo)

Garlic (#litres_trial_promo)

Leeks with lentils, chorizo and eggs (#litres_trial_promo)

Petit pot-au-feu (#litres_trial_promo)

Onions (#litres_trial_promo)

Shallots (#litres_trial_promo)

Spring onions (#litres_trial_promo)

Wild garlic (#litres_trial_promo)

Brassicas (#litres_trial_promo)

Broccoli, calabrese (#litres_trial_promo)

Broccoli, sprouting (#litres_trial_promo)

Brussels sprouts (#litres_trial_promo)

Cabbage (#litres_trial_promo)

Cauliflower (#litres_trial_promo)

Red cabbage (#litres_trial_promo)

Green and leafy (#litres_trial_promo)

Curly kale and Cavolo nero (#litres_trial_promo)

Pak choi (#litres_trial_promo)

Spinach (#litres_trial_promo)

Spring greens (#litres_trial_promo)

Swiss chard (#litres_trial_promo)

Salad leaves (#litres_trial_promo)

Chicory (#litres_trial_promo)

Chinese cabbage (#litres_trial_promo)

Lettuces (#litres_trial_promo)

Purslane (#litres_trial_promo)

Radicchio (#litres_trial_promo)

Rocket (#litres_trial_promo)

Sorrel (#litres_trial_promo)

Watercress and Land cress (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction (#ulink_f815c884-ffe0-5cc8-9544-ce2c9647a429)

I have no choice but to make this introduction relatively short. I’ve used up my space allowance several times over already, and the book has grown royally in length since its original inception. The trouble with writing about vegetables is that there are just so many, so much to say about each one, so many enticing ways to prepare them. This is also the joy of writing about them and more importantly of cooking and eating them.

When I compiled my original list of vegetables that I wanted to include in this book, I decided to concentrate on those that could be bought relatively easily in this country, with just a handful of exceptional rarities (such as chervil root or wild asparagus) thrown in for good measure. The original 60 vegetables have increased to over 70, ranging from the familiarity of the carrot or potato, to the more unexpected taste of oca or jicama. And still I have not shoehorned them all into these pages. Devotees of Chinese arrowheads or waterchestnuts, Indian tindoori or drumsticks or bitter gourds will be disappointed. My daughter complained that there were no recipes for palm hearts, and remains barely mollified by my excuse that I’ve only once bought them fresh, in Spain, and canned vegetables have no place on these pages.

Vegetables have long been something of a passion of mine. This is my second book on vegetables, coming over a decade after the first. I’m still learning about them, coming across new ones, delighting in new and old ways of cooking homely vegetables. I remain fascinated by their differences, their similarities, the way they take starring role, or blend comfortably into the chorus, the way they contrast, the way they add subtlety, the wonderful colours, the rich earthy tones, the sweetness and the textures, the forms, the connection with the land we live in, or with the magic of foreign worlds. I like the notion that the onion is virtually ubiquitous, that other cooks all over the world chop them and fry them just as I do, I love the exoticness of oca, so strange and new in Europe, but as old as the hills of the Andes where they are used without a second thought. Even familiar territory harbours magic discoveries – like the white sprouting broccoli of Leicestershire, or the dramatic purple carrots of Mallorca.

To make the book easier to use (and write) I’ve grouped vegetables together with the cook in mind. This may occasionally make botanists blench, and from them I beg indulgence. To me it makes more sense to slot beansprouts alongside asparagus and cardoons in the ‘shoots and stems’ section, than to keep them with beans and peas. Globe artichokes caused endless arguments, but in the end we kept them next to cardoons to which they are so closely related, even though no-one could ever argue that they are either shoot or stem.

One repetitive refrain runs through the following pages. With almost all vegetables, freshness makes a marked difference in flavour. With some it is more apparent than others. Newly picked spring greens are sensational, for instance, as are peas eaten straight from the pod out in the vegetable garden or allotment where they are grown. These are the kind of simple pleasures we should all have access to. Unfortunately so many of the vegetables sold in our shops have been held in storage for too long, or have been flown so far, that they have lost their brand new sparkle. They will still be in notionally good condition, but no longer in their prime.

This is why I like to buy locally grown vegetables when I can. If they are organic, so much the better. I’m no puritan – I eat cherry tomatoes in the middle of winter from time to time because I can’t bear the thought of going totally without fresh tomatoes for nine months of the year. I regularly forget which day of the month my local farmers’ markets fall on, but when I do get it right, both I and the environment around me reap the benefits. The more we support our local producers, the more opportunities there will be to buy locally grown crops and the more choice we will have.

Above all, however, the message of this book is to make the most of the incredible richness of the vegetable world. This is no health manual, but we all know that vegetables are good for us and we should be eating more of them. It’s not difficult if you give them a chance. Buy widely; choose wisely; cook exuberantly.

Sophie Grigson

Author’s acknowledgements (#ulink_80629f16-937c-51a4-a793-8e0e6934eae2)

My initial encounters with vegetables were, without exception, positive, thanks to my mother, the late Jane Grigson, who cooked them with care and love. I have her to thank for making vegetable-eating a pleasure right from the start, and for encouraging me to experiment with both familiar and new vegetables in later years. More recently, the regular weekly box of vegetables from Riverford Organics has shown me what an extraordinary difference genuine freshness makes to even the most pedestrian vegetables.

I would also like to acknowledge the debt I owe to so many of my friends, who have put up with me moaning about how long it has taken to pen this book, and above all to my editor, Denise Bates, and all of her team at HarperCollins, for their extraordinary patience and forbearance. The wonderful Susan Fleming has fitted copy-editing around the piecemeal delivery of the various sections of the book without a murmur of annoyance, at least in my hearing.

Once again I have been lucky enough to work with William Shaw, one of my favourite photographers (despite his appalling jokes), backed up by a wizard team consisting of the blessed Sam Squire on food and the long-suffering Rosie Dearden on styling – a real diamond, even though she doesn’t like cheese. Weird.

A big thank you to Zoltan and the cheery gang that run the coffee machine at Esporta in Oxford, which is where I retreat to write in relative peace. Annabel Hartog and Leslie Ball have helped me test recipes at home, while Sarah and Jennine have kept house, children and admin running smoothly. Last, but by no means least, a big thank you to the two most important people in my life, Florrie and Sid, who make me laugh, shout, get up in the morning, listen to Radio 1, and question almost every assumption I’ve ever made. They are also pretty good at eating vegetables. What more could a mother hope for?

Publisher’s acknowledgements

Thank you to North Aston Organics for their help with photography of vegetables, and The Conran Shop and Harrods for the loan of props.

Cook’s notes

There is one important element of vegetable preparation that I have omitted from the individual entries for fear of tedious repetition: unless they are to be peeled, all vegetables should be rinsed before use. Beautiful earthy potatoes and other roots will obviously need to be scrubbed as well, so a vegetable brush is an essential piece of equipment. A nail brush fits the purpose well enough, but make sure that everyone in your house knows and respects the fact that it is only to be used for vegetables, and not to scrub engine oil or paint off soiled hands.

In most instances, precise measuring of ingredients is not absolutely necessary. Take vegetable quantities as rough guidelines. Unless you are making something like the carrot cake on page 28 or the potato cakes on page 73, a little more or a little less will not ruin a dish. There is no point wasting a quarter of a potato, when following a recipe for mash, for instance.

On the whole, it makes sense to stick with either imperial or metric measurements. It makes life simpler, if nothing else. I often suggest using handfuls of this or that. Some people find this frustratingly vague, but it allows whoever is using the recipe to make their own decisions about the final strength of flavours in a dish. Ingredients, particularly herbs and vegetables, vary greatly from one batch to another, from one season to another. As cooks, we have to take this in our stride, adding a little bit more here, a little bit less there in order to compensate for fluctuations in flavour.

Unless otherwise specified, eggs are always free range and always large. Spoon measurements are rounded. I use a standard 15 ml tablespoon, 10ml dessertspoon and 5ml teaspoon. Recipes that include olive oil will taste better if made with extra virgin olive oil. Herbs are all fresh, with the exception of bay leaves (good fresh or dried) and dried oregano (use the fabulous Greek rigani, dried wild oregano, if you can get it), which is more exciting than fresh. Pepper and nutmeg should always be freshly ground to maximise spicy impact.

Finally, remember that suggested cooking times are not absolutes. Every oven has its own individual quirks, and settings vary. Similarly the width and make-up of saucepans will affect cooking times. So, check foods regularly as they cook, and if they look done, smell done, taste done, they probably are.

Roots (#ulink_8c50e028-5981-5602-8e6d-75c48aa82634)

Beetroot (#ulink_5db52be5-4565-5237-969e-03697c02fde5)

I’d like to serenade the beetroot. Thank your lucky stars then that this is a book, and you can’t hear me try. Tunefulness was never my strong point. The fact is, though, that beetroot is a miraculous vegetable. Despite extraordinary maltreatment (what else would you call boiling the poor things in vats of malt vinegar?) the beetroot has re-emerged in recent years as something of a star. It features on the menus of the most elevated of restaurants, and it appears regularly in the smartest recipe books, regaining its rightful reputation as a truly delicious, unique vegetable. What other vegetable can offer the combination of full sweet, earthy flavour together with the rich purple-red of a classic beetroot?

If the foregoing leaves you bewildered, it may just be that you have never tasted beetroot at its finest. In other words, home-roast beetroot, cooked slowly to preserve its true flavour. Sure, you can save time and buy it ready-cooked in neat little vacuum packs, but it will have already lost so much to the processing that it is hardly worth the bother. Sure, you can save time and boil your beets in a large pan of water, but again, so much flavour flows out that you end up with a dumbed-down version.

The classic dark purple, staining beetroot is not the only form of the vegetable in existence. The colourways can vary from the palest white spattered with rose, to the summery hue of golden beetroot. Although both occasionally wander on to the shelves of smart greengrocers, or even the better supermarkets, they are hardly common fare. You are more likely to come across them at a farmers’ market. Or, of course, you could grow them yourself and enjoy them pulled straight from the ground, golf-ball sized. Is the taste of these golden beets different? A little, I think, though not radical enough to make headline news. The colour is the main attraction plus the fact that the juice doesn’t stain clothing to anything like the same extent.

Practicalities

BUYING

If possible, buy beetroot by the bunch, complete with leaves. The leaves are the best indicator of freshness. When they are crisply firm, squeaky in their perfection, you know that the beetroot has come out of the ground recently. As it happens, these telltale leaves are also rather good to eat. Like some earthily rich form of spinach, they can be stir-fried or blanched and served up with a knob of butter melting over them, or Italian-style with a slick of olive oil and plentiful freshly squeezed lemon juice. Or, chop fine and use in a stuffing for ravioli. They’re good, too, treated like kale, blanched and fried up with crisp, salty bacon.

As for the beets themselves, only buy them if they are firm with taut skins. Any suggestion of softness or wrinkles tells you that they are older than they should be. It’s one thing for you to keep them hanging around in your vegetable drawer for a few days, but it’s not on for the retailer to palm off old stock on you. It is rare to have much option over size, but if you do, choose medium-sized ones over large, for a gentler, but never wimpy, taste. Snap up teensy beetroots whenever you get the chance, for these are the choicest of all, with a marvellous sweetness and silky-smooth texture when cooked.

COOKING

Although it is not the only way to cook beetroot, by far the best general method is to roast them, guarding all their juiciness and flavour. For most purposes, the process is as follows: wash the beetroots well (but don’t scrub brutally, which will rupture the skin) and trim off the leaves, leaving about 2 cm (

/

in) of stalk in place to minimise bleeding. Do not trim off the root. Wrap each beetroot individually in foil, place in a roasting tin or ovenproof dish and slide into a preheated oven. For the finest results the temperature should be fairly low – say around 150°C/300°F/Gas 2. You should allow 2–3 hours for the beetroots to cook. They will still turn out well at a higher temperature if you want to speed matters up a little, or have something else cooking in the oven – anything up to 200°C/400°F/Gas 6 will do nicely. To test, unwrap one of the larger beetroot and scrape gently at the skin near the root. When it comes away easily, the beetroots are done. Take them out and cool slightly, then unwrap and skin each one.

I don’t boil beetroot, although many people would cook it no other way. Boiling introduces a wateriness that diminishes the joy of good beetroot. If you want to speed up the cooking process, then I would suggest that you think of peeling and cutting up raw beetroot into smaller pieces (say 2–3 cm/1 in cubes), then roasting in a hot oven, tossed with a little olive oil, salt, pepper and some whole garlic cloves and sprigs of thyme, or a good sprinkling of fennel seeds or dill seeds. As with most roast vegetables, they’ll need some 40–60 minutes in the oven – cook uncovered, turning occasionally and adding a little water or orange juice if you think they look worryingly dry. It may be necessary to cover the dish with foil towards the end of the cooking time if the chunks of beetroot are still not quite tender. Sautéed beetroot is also surprisingly delicious – make the cubes a little smaller, say 1–1.5cm (

/

in) across, and sauté them in olive oil or sunflower oil until tender.

PARTNERS

Despite, or perhaps even because of, its distinctive presence, beetroot has an affinity with a remarkable number of other ingredients. In eastern Europe, where it is used most famously to create borscht – beetroot soup in several different forms – beetroot is often combined with aniseed flavours (fennel seed, aniseed, dill and so on) and with soured cream. Try serving cubes of hot cooked beetroot tossed with fresh dill and butter, or fry it briefly with cubes of eating apple and bruised fennel seeds, then serve topped with a spoonful of soured cream (or stir crème fraîche, not soured cream, which will split, into the pan to make a light sauce). Cooked beetroot (puréed or finely diced) is also a brilliant addition to mashed potato, turning it a startling bright pink, which will wow children as much as it amuses parents.

It is, perhaps, in salads that beetroot scores most noticeably, but not the kind of horrorscape of bleeding beetroot lying supine and flabby against miserably limp lettuce leaves, stained gorily with streaks of dark red. No, a good beetroot salad needs a little care in its creation, so that the colour works for it rather than against. Dress the beetroot with vinaigrette while still hot, so that it absorbs some of the tastes, then set aside until ready to plate up with other ingredients. In salads, classic beetroot partners are orange, apple, potato, celery and walnuts in particular. Salty additions also work well – crisp bacon, black olives and anchovy, for instance. On the whole I think it best not to muddle the beetroot with too many partners. The idea should be to highlight its delights, not to mask.

Raw beetroot makes a handsome addition to salads in moderation. The most famous example of this is the French salade nantaise: frisée or blanched dandelion leaves and/or tender lamb’s lettuce (a.k.a. mâche or corn salad), tossed with coarsely grated shreds of raw beetroot and a warm dressing made with bacon frizzled in its own fat and a touch of oil, garlic and red wine vinegar. A gorgeous treat of a salad. I also use raw beetroot with sweet cos lettuce and grapefruit tossed in an animated oriental-toned dressing (see page 381), to totally different effect.

Australian market beetroot dip

The main markets in both Melbourne and Adelaide are thrilling. Bustling and vibrant, they offer superb produce, ranging from fruit and veg, through cheeses, wines, meats and breads, not forgetting dazzling deli stands where you can choose from impressive ranges of freshly made pestos and dips. The brilliant pink of one dip made us pause, then inspired a picnic built around it. The natural sweetness of beetroot balanced by a touch of sourness from the cream and lemon and a waft of spice is very good – eat it with warm pitta bread or batons of cucumber, pepper, carrot and celery.

Serves 6

3 medium fresh beetroots, roughly 300–350g (ll-12oz)

1 teaspoon cumin seeds

1 teaspoon coriander seeds

250g (9oz) soured cream or thick Greek-style yoghurt

1–2 tablespoons lemon juice

salt and pepper

Trim each beetroot, leaving about 3cm (1

/

in) of stalk and the root in place. Wrap each one in foil, place in a baking dish and roast (see above) until tender. Dry-fry the cumin and coriander seeds in a heavy frying pan over a moderate heat until the scent curls temptingly round the kitchen. Tip into a bowl or a mortar and leave to cool, then grind to a powder.

As soon as they are cool enough to handle, skin the beetroots. Set half of one aside; cut up the rest roughly and toss into a food processor. Add all the other ingredients, including the ground spices, and process until smooth. Grate the reserved beetroot or chop finely (messy, I know, but if you want that rather attractive, not-quite-perfectly-smooth texture, it has to be done) and stir into the mixture. Taste and adjust the seasonings.

Serve at room temperature with warm pitta bread, and sticks of carrot, celery, pepper or cucumber.

Beetroot, clementine and pine nut salad with orange dressing

Beetroot and orange work prettily and tastefully together, in every sense of the word. Serve this as a side dish or as a first course. You can make it more substantial by adding big flakes of hot-smoked salmon or trout. Alternatively, tear up a brace of buffalo mozzarella and add them, carefully so that they don’t stain, after the salad has been dished up.

Serves 4–6

4 beetroots, roasted, skinned and cut into wedges

4 clementines or ortaniques

a good handful of flat-leaf parsley leaves

3 small shallots, thinly sliced into rings

3 tablespoons pine nuts, toasted

Dressing

5 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

grated zest of 2 clementines

2–3 tablespoons rice vinegar or cider vinegar

salt and pepper

To make the dressing put the oil and zest into a pan and infuse over a very low heat for 20 minutes. Strain and cool. Whisk the vinegar with salt and pepper, then gradually whisk in the orange oil. Taste and adjust seasonings.

As soon as the beetroot is cooked and cut up, toss with a little of the dressing, then leave to cool. Peel the clementines and slice thinly. Just before serving, toss the clementine discs with the parsley leaves, shallots, pine nuts and the remaining dressing, then arrange in a casual but artful way in a serving dish or on individual plates with the beetroot.

Blushing dauphinoise

This is a dish of heavenly decadence, laden with cream, spiked gently with a touch of horseradish. Like a standard potato dauphinoise, it is something for special occasions only, and there is no point even thinking about making it if you are trying to cut down on fat. I would actually be quite happy to gorge on this as a main course, but more conventionally, it sits well with roast feathered game, or a fine joint of beef.

Allow plenty of time for the dauphinoise to cook – this is not a dish to be rushed. Too high a heat will curdle the cream and blacken the top without ever achieving the melting texture you are aiming for.

Serves 6–8

15g (1/2 oz) butter

300–450ml (10–15floz) whipping cream

300ml (10floz) crème fraîche

3 tablespoons creamed horseradish

550g (11/4 lb) slightly waxy maincrop potatoes, such as Cara or larger Charlottes, peeled and very thinly sliced

500g (1 lb 2 oz) beetroot, peeled and thinly sliced

8 canned anchovies, roughly chopped (optional)

salt and pepper

Preheat the oven to 150°C/300°F/Gas 2. Grease an ovenproof gratin dish thickly with the butter. Beat the whipping cream into the crème fraîche along with the horseradish.

Lay about one-third of the potato slices over the bottom of the buttered dish. Season with salt and pepper, then cover with half the beetroot and sprinkle over half the anchovies, if using. Season again, then pour over enough of the cream mixture to come up to the level of the beetroot. Repeat the layers and then finish with the last third of the potato. Pour over the remaining cream, topping up with more whipping cream if necessary, so that the cream fills all the gaps and rises until about level with the top of the potatoes. Season again.

Bake, uncovered, for about 2 hours, until the potatoes and beetroot are tender all the way through, and the top is richly browned with traces of purple-pink cream bubbling up at the sides. Serve hot or warm.

Carrots (#ulink_a18d3bfb-a8f2-56bd-947c-bd3d03d608a5)

I like carrots. You like carrots. Everyone likes carrots. No point analysing their success – we know that they do a brilliant job bobbing up time and again on plates the world over. Naturally, there are carrots and then there are carrots. And by that I mean that some carrots have the most exquisite sweet carroty flavour, so good you should really just gobble them up raw, and then sadly, other carrots are dull and lacklustre, providing, one hopes, vitamins and other good-health requirements, if not a great deal in realms of pleasure.

There is no telling before the first bite, which makes buying carrots the tamest form of Russian roulette going. There are people who swear blind that organic carrots taste better than non-organic, and often they do. But no one has yet managed to convince me that it is their organicness that makes the difference. No, I reckon that it’s a lot more to do with variety, conditions in the field, freshness and luck, as well as good husbandry.

You may also not be aware that the orange carrot is a comparatively modern phenomenon, and not one that occurs in the wild. The true colour of the carrot is off-white in the case of the Mediterranean native, or purple or red when growing in more exotic places like Afghanistan, though one imagines that there aren’t many left growing in the wild there. You can, however, find purple carrots closer to home in more hospitable surroundings. They are still eaten on the island of Mallorca – a trip to the excellent covered market in the heart of Palma is all it takes to track them down. The difference in taste is minimal but the colour is sheer drama.

Practicalities

BUYING

A happy carrot is firm from tip to stem, no bruising or discoloration, with a pleasing light carroty smell. The slightest hint of flabbiness spells disaster, and slimy ends or rotting soft spots are to be avoided like the plague.

Buying carrots in bunches, with a duster of fluffy green leaves, is the only way you can be sure that they are newly tugged from the earth, but since they store rather well (especially with a dusting of soil still protecting them) freshness is not the critical issue it is with so many other vegetables. Take advantage of it when bunched carrots are on offer, and for the rest of the year pick out carrots of similar size to each other so that they cook evenly. Really small mini carrots, cute though they are, often taste of very little. Costwise it makes sense to go for larger carrots, which should have developed more depth of flavour. The swelling of ginormous carrots, on the other hand, may be partially due to too much water, so they have a tendency to dullness. These are crude generalisations, so there will always be exceptions, but they are the best I can offer as guidelines.

Store carrots either in an airy, dry, cool spot, or in the vegetable drawer of the fridge.

COOKING

Peeling or scraping or just a quick scrub? All three have their supporters, but personally I go for the peeling unless my carrots are pristine organic roots of impeccable freshness. Scraping is a messy business, I find, and slower than peeling. I know that peeling is wasteful, but you could save the peelings for the stockpot, or the compost, or even get yourself a backyard pig to feed them to. There is no doubt that commercially grown carrots must be either peeled or scraped in order to eliminate pesticide residues. When it comes to organic carrots, by definition free from pesticides, you might well consider that a good wash is sufficient.

Raw carrots are under-used. I love them in salads, coarsely grated and dressed perhaps with a mustardy vinaigrette, studded with raisins or currants and toasted pine nuts or walnuts. Or to give a more exotic air, try tossing them with lemon juice, rosewater, a little sugar, salt and a touch of sunflower oil, Moroccan-style. Grated carrots make a handsome addition to a sandwich, too, especially with cheese or hummus.

There are times when ‘over’-cooked carrots are wonderful – in a stew, say, where they’ve donated some of their sweet flavour to the other ingredients in exchange for some of theirs. However, carrots that have been left to boil in plain water for too long have received nothing in compensation but water, ergo they taste of very little. Simmered or boiled or steamed carrots do not take long to cook – the thickness of the pieces dictates exactly how long, but think in terms of 4–6 minutes. That should be long enough for the heat to have developed the flavour, but not so long that it all leaches out. If you know that the carrots you are about to cook are not very sweet, try adding a teaspoonful or two of sugar to the cooking water.

Boiled perfectly, a good carrot retaining just the right degree of firmness is a pleasure to eat plain, but even nicer with a gloss of melted butter, or fragrant lemon olive oil. In the summer I add a speckling of chopped lemon balm or mint; in the winter thyme or savory enhances the flavour.

Although boiling or steaming will always remain the principal way we cook carrots, once in a while have a go at frying (see the salad recipe overleaf) or stir-frying them, cut into slender batons. Roasted carrots should become part of your regular repertoire, if they aren’t already. They taste divine, and are sooo very easy. Just peel the carrots and halve or quarter lengthways if they are huge, then toss them into a roasting tin with a little extra virgin olive oil, a handful of garlic cloves (no need to peel), a few chunky sprigs of thyme or rosemary and a scattering of coarse salt. Roast in a hot oven (200–220°C/400–425°F/Gas 6–7) for around 40–45 minutes, stirring once or twice, until patched with brown and extremely tender.

PARTNERS

Since carrots are so amiable, there are few tastes that don’t marry well with them. I don’t much like the idea of canned anchovies or chocolate with carrots, but I’m hard pressed to think of much else to avoid. Carrots love to be cooked with spices, with herbs, with garlic and chilli, in sweet dishes (such as carrot cake), in pickles, with meat or fish, with cheeses, and of course with other vegetables. This, I imagine, is one of the reasons that you bump up against carrots wherever you eat in the world. And this is also why we should value them more than we do.

Fried carrot salad with mint and lemon

I’ve been making this salad for years and years and it still seems just as fabulous as it did way back in the mists of time. It comes down to taking a bit of time over the frying, so that the carrots soften as their inner sugars caramelise and every mite of flavour in them concentrates itself. Add plenty of fresh lemon and lots of breathy mint and you have a small miracle of a salad on your hands. If you don’t believe me, have a go.

Incidentally, if you prefer, you can roast the carrots in a hot oven (around 220°C/425°F/Gas 7) with a generous dousing of good olive oil for some 30–40 minutes, until browned and tender.

Serves 4

450g (1 lb) carrots (smaller rather than larger)

3 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

juice of 1/2 lemon

2 tablespoons chopped mint

salt and pepper

If using small carrots, top and tail them, then halve lengthways and cut each piece in half. Treat medium-sized carrots in much the same way, but quarter them lengthways.

Heat the oil in a wide, heavy frying pan and add the carrots. Fry slowly, shaking and turning every now and then, until the carrots are patched with brown and tender. This should take about 15 minutes. Tip into a bowl and mix with the lemon juice, mint, salt and pepper. Leave to cool and serve at room temperature.

Carrot and pickled pepper soup

For this soup I use small, round, sweet-sharp pickled red peppers with a bit of a kick to them, to throw a shot of excitement into a comforting carrot soup. If you can’t find any good red pickled peppers, then you could replace them with pickled jalapeño peppers – but go gently, as the heat can be more intense and the colour is less attractive.

Serves 4–6

1 onion, chopped

500g (1 lb 2 oz) carrots, sliced

1 bouquet garni (3 sprigs lemon thyme, 1 sprig tarragon, 2 sprigs parsley, 1 bay leaf), tied together with string

2 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

2 tablespoons pudding rice

4 hot or 6 mild pickled red peppers, roughly chopped

1.5 litres (23/4 pints) light chicken or vegetable stock

lemon juice

salt and pepper

To serve

a little soured cream (optional, but good)

roughly torn coriander or parsley leaves

4–6 pickled red peppers, sliced

Sweat the onion and carrots with the bouquet garni and oil for 10 minutes in a covered saucepan over a gentle heat. Now add the pudding rice and the peppers and stir until the rice is glistening with the oily juices. Add the stock, salt and pepper and bring up to the boil, then reduce the heat and simmer for 10–15 minutes, until the rice and carrots are tender. Draw off the heat and cool slightly, then liquidise in several batches. Add a little more stock or water if the soup is too thick for your taste, and stir in a couple of squeezes of lemon juice. Taste and adjust seasoning. Reheat when required.

To serve, ladle into soup bowls, add a few small dollops of soured cream and then top with the coriander or parsley and sliced peppers.

Carrot falafel with tomato and carrot salad

The best falafel I’ve eaten over the decades have almost invariably been bought from street stalls and eaten on the hoof, jostling for space with tomato, cucumber and lettuce in the cavity of a warm pitta bread.

Back at home, lacking the ambience of the bustling street, I resort to making my own falafel, lightened with the natural sweetness of grated carrot, and served as a first course with a fresh and invigorating salad. They’ve not got the street–stall shimmer, but the taste is terrific, nonetheless.

In terms of culinary notes, the most important is that you should never ever even think of using tinned chickpeas for making falafel. They have to be made with dried chickpeas, soaked overnight, to get the right texture and firmness. No debate on this one. The second, a follow-on from the first, is that you mustn’t rush the cooking. If the temperature of the oil is too high, the falafel will never cook through to the centre.

Serves 4–6

125 g (41/2 oz) dried chickpeas, soaked overnight

6 spring onions, trimmed and roughly chopped

1 large clove garlic, chopped

2 carrots, grated (about 200g/7 oz)

30g (1oz) parsley leaves, roughly chopped

1 teaspoon ground cumin

1/2 teaspoon baking powder

sunflower and olive oil for frying

salt and pepper

To serve

leaves from a small bunch of coriander

18 mini plum tomatoes, halved

1 shallot, halved and thinly sliced

1 carrot, coarsely grated

juice of 1/2 lemon

2 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

3–4 tablespoons thick Greek-style yoghurt

To make the falafel, drain the chickpeas and place in the bowl of a food processor with the spring onions, garlic, carrots, parsley, cumin, baking powder, salt and pepper. Process to a smooth paste. You should be able to roll it into balls that hold together nicely – not too soft and soggy, nor irritatingly crumbly.

Take a little of the mixture and fry in a little oil. Bite into it and consider whether the seasoning needs to be beefed up. Act upon your thoughts immediately. Now, scoop out dessertspoonfuls of the mixture and roll into balls, then flatten gently to a thickness of around 1.5 cm (

/

in). Cover and set aside until needed.

Shortly before serving, heat up a 1cm (

/

in) depth of sunflower oil, or mixed sunflower and olive oils, in a saucepan. When good and hot, add a few of the falafel and fry for some 3 minutes on each side, until crustily browned and cooked through. You may have to try one to check that you’re getting the timing just right. What a pity – just don’t try too many.

While they are in the pan, mix the salad ingredients – coriander, tomatoes, shallot, carrot, lemon juice and oil – and divide among plates (or pile into one big bowl). Serve the hot falafel with the salad and a dollop of thick yoghurt on the side.

Braised pheasant (or guinea fowl) with carrots, Riesling and tarragon

This is, in essence, a smart pot-roast, with the carrots and Riesling flavouring the natural cooking juices of the birds. If you have a brace of pheasants, there should be enough to feed six comfortably, but a guinea fowl will probably not satisfy more than four. Either way, the finished result is smart enough to grace a dinner party, but easy enough to serve as a good supper dish when you need something of a boost.

Serve the birds and their sauce with steamed or boiled new potatoes and some sort of green vegetable, to counterpoint the tender sweetness of the carrots.

Serves 4–6

15g (1/2 oz) butter

1 tablespoon sunflower oil

2 pheasants or 1 plump guinea fowl

1 onion, chopped

3 cloves garlic, sliced

500g (1lb 2oz) carrots, cut into batons

4 sprigs tarragon

150 ml (5 floz) dry Riesling

100 ml (3 1/2 floz) double cream

salt and pepper

Heat the butter with the oil in a flameproof casserole large enough to take the birds and all the carrots. Brown the pheasants or guinea fowl in the fat, then remove from the casserole. Reduce the heat, then stir the onion and garlic into the fat and fry gently until tender. Add the carrots and tarragon and stir around for a few minutes, then return the pheasants or guinea fowl to the pot, nestling them breast-side down in amongst the carrots. Pour over the Riesling and season with salt and pepper. Bring up to the boil, then cover with a close-fitting lid. Turn the heat down low and leave to cook gently for 1 hour, or a little longer if necessary, turning the pheasants or guinea fowl over after about half an hour.

Once the birds and carrots are tender, lift the birds out on to a serving plate and keep warm. Stir the cream into the carrots and juices and simmer for 2 minutes or so, then taste and adjust seasoning. Spoon around the birds and serve immediately.

Carrot cake

Everyone knows that carrot cake is a very good thing, indeed. What a cheery thought it is that you can have your cake and eat vegetables at the same time.

This is the recipe I return to regularly, after playing away with less successful variations. I’m not usually a big fan of baking cakes or pastry with wholemeal flour, but for once it makes absolute sense, absorbing some of the moisture that the carrot provides, and giving the substance the cake needs.

Serves 8–12

250g (9oz) light muscovado sugar

250ml (9floz) light olive oil or sunflower oil

4 large eggs

2 tablespoons milk

250g (9oz) wholemeal flour

2 rounded teaspoons baking powder

60g (2 oz) ground almonds

2 tablespoons poppy seeds

125g (41/2 oz) shelled walnuts, roughly chopped

250g (9 oz) carrots, grated

Frosting

200g (7oz) cream cheese

200g (7oz) butter, softened

250g (9oz) icing sugar, sifted

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

12 walnut halves to decorate

Preheat the oven to 180°C/350°F/Gas 4. Base-line two 20cm (8in) round cake tins with baking parchment and grease the sides. Whisk the sugar with the oil, eggs and milk. Mix the flour with the baking powder, ground almonds, poppy seeds, walnuts and carrots. Make a well in the centre and add the sugary liquids, scraping the last of the sugar from the bowl. Mix the ingredients thoroughly.

Scrape into the two prepared cake tins and bake for 40–45 minutes until firm to the touch – check by plunging a skewer into the centre. If it comes out clean, then the cake is cooked. While the cake is baking, beat the cream cheese with the softened butter, icing sugar and vanilla extract to make the frosting.

Let the cakes cool in their tins for 5 minutes, then turn them out on to a wire rack. Leave to cool completely, then sandwich together with about one-third of the frosting. Spread the remaining frosting over the top and down the sides, then decorate with the walnut halves.

Celeriac (#ulink_8caec55c-c5a8-5509-9f42-31e1a0399008)

Perhaps the most brutish-looking of vegetables (swede competes for the title, and it’s hard to decide which merits the crown most), celeriac is a form of celery with an absurdly swollen rootstock, known technically as a corm. Both celeriac and celery share the Latin name Apium graveolens, even though they look so very different. When the stems are left on celeriac, sticking up like a brush, the connection is more obvious. The stems are slender, but topped with the same leaves, as if someone had squeezed hard on the broad succulent stems of a head of celery, forcing all the liquid back down into the root to puff it up like a balloon. The odd thing is that celeriac doesn’t taste at all like celery. Celeriac tastes of nothing but itself. Most people love it, and many people find it infinitely preferable to celery.

So, discount the exterior and concentrate on the firm, cream-hued interior. Solid and dense and generously proportioned, it is a remarkably delicious vegetable. I’ve never really understood why we don’t use it more: over in France it is the substance of one of their favourite mainstream salads, sold in every charcuterie and supermarket, as popular as and infinitely better than, most of the coleslaw consumed here. Yet here it is still considered something of an outsider, idly hovering on the fringes of popularity. How much longer before it breaks through to become a household name?

Oddly enough, celeriac sales were boosted by the vogue for the Atkins diet. Celeriac is, apparently, very low in carbohydrate. What a godsend for those who missed potatoes. Here was a great substitute, particularly when mashed with shedloads of cream and butter. Now that the Atkins diet is no longer as fashionable as it once was, I hope that the celeriac habit endures – it is far too engaging a vegetable to drop the minute the diet is over.

Practicalities

BUYING

Celeriac is always big, but don’t buy the most colossal ones, as these may have swelled up so far that the centre has become spongy or hollow. Be satisfied with plain big. Choose celeriac that is firm and heavy with no soft, bruised spots. Store it in the vegetable drawer of the fridge, where it will keep happily for a week or more.

COOKING

Celeriac can be cooked in a number of ways, but before that you have to take off the outer layer and the gnarled tangle of roots at the base. I usually slice the celeriac thickly then discard the roots and cut away the skin around the edge of each disc. If I’m boiling the celeriac, I then hack it into big chunks, ready to drop into the pan. If not used immediately, celeriac discolours, so once cut drop it into a bowl of water acidulated with the juice of

/

lemon or a dash of wine vinegar.

The most cherished way to serve celeriac is mashed, either à la Atkins, in other words pure celeriac and lots of rich cream and butter, or – rather nicer, both in texture and flavour – mashed with equal quantities of potato, a large knob or two of butter and some milk. Either way it begs for plenty of salt and a good scraping of nutmeg. Another fine variation that I make occasionally, especially as Christmas approaches, is a mash of celeriac and chestnuts – true, the colour is muddy, but the taste is divine. Unless you are saintly, use vacuum-packed cooked chestnuts, and mash with double the quantity of celeriac, butter and cream. Nutmeg is essential. Distract from the colour with a sprinkling of chopped chives and a knob of melting butter in the centre of the hot mash.

As with most vegetables, celeriac can be sautéed (cut into small cubes) over a lively heat, or roasted in the oven, tossed in olive oil. To make celeriac chips, parboil thick batons of celeriac (just 2–3 minutes will do the trick), drain well and then deep-fry, or shallow-fry, or toss with oil and roast in a hot oven for 10–15 minutes.

I adore a celeriac and potato dauphinoise, rich and creamy. For this one, I usually blanch the slices of celeriac and potato in boiling salted water for a couple of minutes, before layering and baking slowly in the oven until heavenly soft and tender.

Raw celeriac is rather good too. I don’t like it grated – a bit slushy – but I do like it cut into juliennes (thin batons), which increases the prep time, but is worth the bother. Remember to toss it with lemon or lime juice as you cut it, to prevent excessive browning. Although there is no reason why it shouldn’t be added to any number of salads, the classic is always going to be céleri rémoulade, for which I give a recipe overleaf. Frankly, you just can’t beat it.

SEE ALSO CELERY (PAGE 124).

Roast chicken with apple, celeriac and hazelnut stuffing

Celeriac makes a good basis for a stuffing, a strong enough flavour to come through without fighting the taste of the chicken. The celeriac ‘chips’ around the outside semi-simmer and semi-roast as the bird cooks, absorbing some of the juices from the chicken for extra flavour.

Serves 4

1 plump and happy free-range chicken a little olive oil

1/2 celeriac, peeled and cut into ‘chips’ salt and pepper

Stuffing

1/2 celeriac, peeled and finely diced

1 onion, chopped

2 cloves garlic, chopped

30g (1oz) butter

8 sage leaves, chopped

1 eating apple, cored and diced small

40g (11/2 oz) shelled, skinned hazelnuts, roasted and chopped

80g (scant 3oz) soft white breadcrumbs

1 egg, lightly beaten

Preheat the oven to 200°C/400°F/Gas 6.

To make the stuffing, begin by sautéing the celeriac, onion and garlic together in the butter until tender – take plenty of time over this, say 10 minutes or more, so that their flavours really get a chance to develop. Stir in the sage leaves and cook for a further 30 seconds or so. Now mix the vegetables and buttery juices with the apple, hazelnuts, breadcrumbs, seasoning (be generous with it) and enough beaten egg to bind.

Fill the cavity of the chicken with the stuffing. You’ll probably have more than you need, so pack the remainder into a shallow ovenproof dish and bake alongside the bird until browned and hot – it won’t taste as good as the stuffing inside the bird, but it gets the crisp crust as a bonus.

Place the stuffed bird in a roasting tin or shallow ovenproof dish and smear a little olive oil over its skin. Season generously with salt and pepper. Pour a small glass of water around the bird and surround with the celeriac chips. Roast for about 1

/

hours, basting the bird occasionally with its own juices (add a little more water if it needs it) and turning the celeriac chips occasionally – they should soften and catch a little brown here and there.

Test to make sure that the chicken is cooked by plunging a skewer into the thickest part of the thigh – if the juices run clear then it is done. If they run pink and bloody, then get the whole lot back into the oven for another 15 minutes and then try again.

Let the chicken rest in a warm place for 20 minutes before serving.

Céleri rémoulade

Whenever we’re in France we head straight for the charcuterie to buy garlic sausage and a tub of céleri rémoulade. In this instance ‘céleri’ is short for ‘céleri-rave’, in other words, celeriac. ‘Rémoulade’ indicates that it is tossed in a mustardy mayonnaise, to transform it into one of France’s favourite salad dishes. Few French domestic cooks ever make their own – why bother when the shop-bought céleri rémoulade is so good? Outside France it is another matter – especially if you make your own mayonnaise, which takes no time at all in a processor or liquidiser. The celeriac itself is best cut by hand, rather than grated, which inevitably produces an over-fine mushy salad. Soften it to agreeable floppiness by soaking in lemon juice and salt for a while.

Either serve your céleri rémoulade as one amongst a bevy of salads, or make it a first course, perhaps accompanied by some lightly cooked large prawns, or thin slices of salty Parma ham.

Serves 6

1 small celeriac

juice of 1 lemon

2 tablespoons single cream

3 tablespoons home-made mayonnaise

2 teaspoons Dijon mustard

salt and cayenne pepper

Peel the celeriac, removing all those knobbly twisty bits at the base. Now cut the celeriac in half, then cut each half into thin slices – you’re aiming roughly at about 3–5mm (

/

–

/

in) thick, no more. Cut each slice into long, thin strips. Toss the celeriac with the lemon juice as you cut, to prevent browning, then once all done, season with salt and cover with clingfilm. Set aside for half an hour or so to soften.

Drain off any liquid, then toss the celeriac strips with the cream, mayo, mustard, salt and cayenne. Taste and adjust seasoning, then serve.

Speedy mayonnaise

I’ve given up on making mayonnaise the proper, old-fashioned way. Nowadays, I opt for the quick liquidiser method, which yields up a mayonnaise that is every bit as good and so much less stressful.

Two brief notes. Avoid the temptation to increase the amount of olive oil. In quantity it gives an unpleasant bitterness. The second is the old familiar: as home-made mayonnaise inevitably contains raw egg, do not offer it to the very young, the old, pregnant women, invalids.

Makes roughly 250ml (9floz)

1 egg

1 tablespoon very hot (but not boiling) water

1 tablespoon lemon juice

250ml (9floz) sunflower or grapeseed oil

50 ml (2floz) extra virgin olive oil

salt

Break the egg into the goblet of the liquidiser and add the hot water. Whirr the blades to blend, then add the lemon juice and salt. Measure the oils into a jug together. With the motor running, pour the oil into the egg, in a constant stream, until it is all incorporated. By this time, the mayonnaise will be divinely thick and glossy. Taste and adjust the seasoning.

Roast celeriac with Marsala

This is a repeat recipe, originally printed in my book Taste of the Times, which is now out of print. It is so good, however, that I have no qualms about including it again here. As the celeriac roasts, it absorbs some of the raisiny flavour of the Marsala (but not the alcohol, which just burns off), whilst caramelising to a golden, sticky brownness. Excellent with game, in particular.

Serves 4

1 medium-large celeriac

a little sunflower oil

a knob of butter

5 tablespoons sweet Marsala

salt and pepper

Preheat the oven to 180°C/350°F/Gas 4. Cut the celeriac into 8 wedges, then trim off the skin as neatly and economically as you can. Toss the wedges in just enough oil to coat. Smear the butter thickly around an ovenproof dish, just large enough to take the celeriac wedges lying down flat (well, flattish, anyway). Lay the celeriac in the dish, season with salt and pepper and pour over the Marsala.

Roast for about 1 hour, turning the wedges and basting every now and then, until richly browned all over and very tender. You may find that you have to add a tablespoon or two of water towards the end to prevent burning.

Chervil root (#ulink_7b471492-2880-54c0-8681-7409e3664a6f)

The rarity of chervil root is a small tragedy. I have come across them a mere three or four times in my adult life and I regret profoundly that they are not more common, for they are nothing short of delicious. I first discovered them in a market near Orléans in France. This is their home region. However, even in France they remain bemusingly rare. This may partly be due to their appearance. They don’t look at all promising. Small, brown, dirty cones, looking for all the world like a pile of rough-hewn, old-fashioned children’s spinning tops, they don’t exactly shout ‘buy me’. It may well be that you or I have strode past them without even noticing their presence. Oh that it weren’t so. These insignificant morsels are blessed with a remarkable flavour, something like a cross between a chestnut and a parsnip, and if only you could lay your hands on them, I have no doubt that they would soon become all the rage.

Practicalities

BUYING

There’s no point angsting about freshness – just grab hold of them if you are lucky enough to find any. Ideally, they should be pleasingly firm, but personally I’d snap them up even if they were just a mite softer and wrinklier – the taste is still good, though they are harder to peel in this state.

COOKING

Give them a good scrub to remove any dirt (however much elbow grease you employ, the skin will remain unappealingly grubby-looking). The skin is edible, but not especially so. Peel the little darlings before cooking for the best results. They taste fab just simmered in salted water until tender (like a parsnip, this is not a vegetable that benefits from the al dente school of cooking), drained well and then finished with a knob of butter. Even more devastatingly divine, however, are roast chervil roots. Again peel before cooking, then roast in a little olive oil or oil and butter in the normal fashion, until tender as butter inside, lightly browned and a little chewy outside.

PARTNERS

Cooked this way, they go spectacularly well with roast beef, or a good steak. I dare say that chervil root has enormous potential and could be mashed, chipped, souped and so on. One day, maybe, I’ll get to find out, but that will just have to wait until the day I can source them regularly, and easily. Roll on that day.

Hamburg parsley (#ulink_11f78771-ff60-5a75-a8d8-a68e49ebca79)

As entries go, this one will be very short. Not because Hamburg parsley doesn’t rate, but more because it has become increasingly hard to find. I don’t think I’ve seen it for sale for the best part of a decade, more’s the pity. Therefore my aim now is merely to prime you, just in case you stumble across a tray of Hamburg parsley unexpectedly. If you do, please buy some and encourage the seller/grower to spread the word.

Although it looks like a shocked parsnip, colour washed out to ghostly off-white, and is about the same size and shape, Hamburg parsley is actually nothing more unusual than a form of the commonest of herbs, parsley. They share the same Latin name, Petroselinum crispum, but the energy flows down to the root of the Hamburg variety, swelling it out to a satisfying girth. Not for nothing is it also known as parsley root. It is far less sweet than a parsnip and does have a distinct parsley zing, which is surprising at first.

COOKING

Although you could serve it as a straight vegetable, just boiled and buttered, the flavour is strong. In practice, it is more usual to add it in moderation to stews and soups, cut up into chunks. In this context, it blossoms, imparting something of its parsley scent to the whole, and absorbing other flavours to mollify its own in a most beguiling manner. If you have only one or two roots, you might prefer to boil and mash them with double or triple quantities of potato and plenty of butter to make excellent, parsley-perfumed mash to accompany some dark, rich, meaty stew.

Jerusalem artichokes (#ulink_8c8bec33-1515-5f8a-a566-d423f1f628be)

Once upon a time, many centuries ago, intrepid explorers crossed the Atlantic Ocean at great peril and discovered all sorts of miraculous things. There were potatoes and tomatoes and chocolate and gold. There were chillies to make up for a dismaying lack of black pepper. Less lauded and celebrated, however, was the discovery of the Helianthus tuberosus. It belongs to a later period of exploration and intrepidity, when the pioneering spirit of the first settlers in North America led them to the flaps of Native American tepees. This time, along with turkeys and cranberries, they also sampled the delights of one of the windiest vegetables known to man, the knobbly Jerusalem artichoke.

Not as celebrated as potatoes or tomatoes and never exported with quite the same passionate love/hate devotion, nonetheless the Jerusalem artichoke was a significant addition to the greater vegetable repertoire. It has since gone in and out of fashion and now hovers amongst the bevy of vegetables that are almost but not quite popular, but still beloved by many devotees.

I count myself amongst them. Jerusalem artichokes are delicious and special and still remarkably seasonal. This is a crop that belongs to the late autumn and winter, a root vegetable with the gorgeous natural sweetness that slow growth in the darkness of moist earth imparts. Knobbly they may be, but the texture of the cooked tuber is smooth and gently crisp, defying comparison with others.

There is, as the name suggests, a passing resemblance in flavour to globe artichokes but there is no way you could confuse the two. The Jerusalem artichoke is very much its own man. With one half of the name explained, you might then wonder why a native American vegetable has acquired a Levantine moniker. The answer is simple: corruption. Not fraudulent illegal corruption, but verbal. The Jerusalem artichoke is closely related to the sunflower and, like the sunflower, its open-faced flower follows the sun from morning to evening. The Italian for sunflower is ‘girasole’, translating literally as turning towards the sun. ‘Jerusalem’ is merely a mispronunciation of this, lending an added exoticism to a vegetable that has travelled far.

Not so exotic is its propensity to flatulence. Theories abound as to how to minimise the after-effects, but to be frank I’ve never been that bothered. Except once, when I was breastfeeding my first child. A generous helping of Jerusalem artichokes gave rise to a distinctly sleepless night, and a very cranky mother and baby. Lactating mothers apart, I would suggest that you just accept that Jerusalem artichokes will induce wind to some degree, and ignore it. The taste is too good to let a minor inconvenience put you off.

As if to make up for their inherent windiness, Jerusalem artichokes are often grown as windbreaks along the edge of a vegetable garden. They are easy and undemanding, ideal for the not-so-green-fingered gardener, reproducing silently and prolifically underground as the tall stems stretch upwards to protect less hardy plants.

Practicalities

BUYING

There are two key things to bear in mind when buying Jerusalem artichokes. The first is that they should be fairly firm with just the slightest give (i.e. not as hard as a potato, but firmer than a tomato). The second is that it is worth spending a few extra seconds sorting through the box to select the least knobbly tubers. Charming and funny though the more knobbly ones look, the fact is that you are going to have to peel the wretched things at some point. Smaller knobbles will just have to be sheared off and discarded; larger ones may ultimately go the same way if you can’t be bothered to peel each and every one of them. In other words, you pay for a lot of waste.

COOKING

The next issue is when to peel them. My mum always used to peel them after boiling – she thought it easier – but I veer the other way, preferring to peel them before they go into any pan. The first method is probably more economical in that it minimises waste, as the skin just pulls away, but it does mean that reheating will be necessary. Peeling them first means that they can be whisked straight from the pan to the table, which suits me better. Be aware, however, that peeled raw Jerusalem artichokes discolour very quickly. Within minutes they take on a rusty colour as they oxidise. To prevent this (especially if there is to be a time lapse between peeling and cooking) drop the prepared Jerusalem artichokes into a bowl of acidulated water (i.e. water with the juice of

/

lemon, or a tablespoon or two of vinegar, swished in).

Jerusalem artichokes can be cooked in most ways. Plainly boiled or steamed, tossed with a squeeze or two of lemon and a knob of butter, and served hot is the most obvious. But equally as good (if not better) are roast artichokes, bundled into the oven still swaddled in their skins (no choice here), with a small slick of olive oil and a sprinkling of salt. Once cooked it is up to each consumer to decide whether to eat the skins or not. I’ve often included Jerusalem artichokes in stir-fries (they make a rather good substitute for water chestnuts), where if you get the timings right they retain a slight crunch, alongside the characteristic sweet nuttiness. They go fantastically well with chicken in a creamy stew, even better encased in puff pastry to transform the stew into a pie.

PARTNERS

Some people like them raw in salads. I don’t. I do, on the other hand, like them lightly cooked and cooled in a tarragon or chervil-flecked dressing, to stand as a salad on their own, or to add to other ingredients. Nut oils – hazelnut or walnut – bring out the natural nutty taste of the vegetable. Prawns (or lobster if you fancy something really smart) and Jerusalem artichokes on a bed of watercress or rocket make a most appetising starter or main course in the middle of the cooler months. Grill or bake a rasher or two of pancetta or dry-cured bacon until crisp, perch it on top and you’re heading towards perfection.

SEE ALSO GLOBE ARTICHOKES (PAGE 139).

Jerusalem artichoke broth

I have fond memories of my mother making Palestine soup way, way back, in the cubbyhole of a kitchen in our holiday home in France. As a name for Jerusalem artichoke soup it now strikes one as a distinctly tasteless joke, but to be fair it pre-dates the creation of Israel in 1948. When I came to look up the soup in her Vegetable Book (Michael Joseph, 1978) it turns out to be a puréed cream of a soup, and not at all the clear broth studded with knobbles of sweet, semi-crisp artichoke that I thought I recalled. Memory plays strange tricks…

This is how I now prefer to make the soup, the intensity of slow-cooked vegetable sweetness shot through with a balancing measure of white wine vinegar. All in all, it is a deceptively simple creation, obviously at its best when simmered in a home-made stock, but still more than palatable when a decent instant vegetable bouillon is substituted.

Serves 6

1 large onion, halved and sliced

675 g (11/2 lb) Jerusalem artichokes, peeled, halved and sliced

2 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

4 good sprigs thyme

1 bay leaf

1 litre (13/4 pints) chicken or vegetable stock

2 tablespoons white wine vinegar

2 tablespoons roughly chopped parsley salt and pepper

To serve (optional)

6 thick slices baguette

150g (5oz) single Gloucester, mature Cheddar or Gruyèe cheese, coarsely grated

Put the onion, artichokes and oil into a pan and add the thyme and bay leaf, tied together with string. Cover and sweat over a low heat for some 15 minutes, stirring occasionally. Now add the stock, vinegar, salt and pepper (be generous with the pepper, please) and bring up to the boil. Simmer for 10 minutes, then taste and adjust seasoning. Discard the thyme and bay leaf and serve, sprinkled with parsley.

If using the bread and cheese, toast the baguette lightly on both sides under the grill. Then, just before serving, top with grated cheese and slide back under the grill to melt. Float a slice of cheese on toast in each bowl of soup as you serve.

Chicken and Jerusalem artichoke pie

Jerusalem artichokes impart an enormous depth of flavour to any sauce or stock they are simmered in, which is what makes this otherwise fairly classic chicken pie so appetising. For a dish like this, I use a mixture of breast and leg meat, cut into large chunks. The darker flesh stays moister throughout the double cooking.

Serves 8

500g (1 lb 2 oz) puff pastry

plain flour

1 egg, lightly beaten

Filling

1 onion, chopped

2 cloves garlic, chopped

30g (1oz) butter

500g (1 lb 2 oz) Jerusalem artichokes, peeled and cut roughly into 1.5cm (5/8 in) thick chunks

finely grated zest of 1 orange

150ml (5floz) dry white wine

21/2 tablespoons plain flour

300ml (10floz) chicken stock

700g (1 lb 9oz) boned chicken, cut into 3–4cm (11/2 in) chunks

150ml (5floz) double cream

salt and pepper

Begin with the filling. Fry the onion and garlic gently in the butter until tender without browning. Now add the Jerusalem artichokes, orange zest and white wine and boil down until the wine has virtually disappeared. Sprinkle over the flour and stir for a few seconds so that it is evenly distributed. Gradually stir in the stock to make a sauce. Season with salt and pepper, then stir in the chicken. Now cover and leave to simmer away quietly for some 10 minutes or so, stirring occasionally. Then uncover and simmer for 5 minutes, until the sauce has thickened. Stir in the cream and cook for a final 3 minutes. Taste and adjust the seasoning. Spoon into a 1–1.5 litre (1

/

-2

/

pint) pie dish and leave to cool.

Roll out the pastry thinly on a floured board. Cut out a couple of long strips about 1cm (

/

in) wide. Brush the edge of the pie dish with the beaten egg. Lay the strips of pastry on the edge, curving to fit and cutting so that they go all the way around but don’t overlap. Brush them with egg, then lay the remaining pastry over the top. Trim off excess, and press the pastry down all around the edge to seal. Use the pastry trimmings to make leaves or flowers or whatever takes your fancy, and glue them in place with the egg wash. Make a hole in the centre so that steam can escape. Chill the pie in the fridge for half an hour.

Preheat the oven to 220°C/425°F/Gas 7. Brush with egg wash and place in the oven. After 10–15 minutes, when the pastry is golden brown, reduce the heat to 190°C/375°F/Gas 5. Continue baking for a further 20–25 minutes. Serve hot.

Jicama (#ulink_771c9974-8961-5067-90cf-517f4f75cb11)

Sometimes the best place to hide something is in a place so obvious that no-one but those in the know think to look there. Jicama is just such a cleverly hidden secret, for sale openly in our towns and cities, if only you know where to look. No point asking for it in supermarkets, in farm shops, in greengrocers, in farmers’ markets. No point in asking for it by this name, either, even if you have the finest South American accent – ‘hee-kah-ma’. You must, instead, replace it with a far duller name: yam bean. This is odd because it is neither yam, nor bean, and bears no resemblance to either.

It looks something like a chunky turnip, with a matt mid-brown skin. In other words, it has a thoroughly undistinguished appearance, which makes hiding it all the easier. The place to look, in this innocent game of vegetable hide and seek, is in the vegetable racks of a Chinese supermarket, where you are virtually guaranteed to discover a plentiful supply of jicama/yam bean.

Apart from the fun of the game, there is a point to tracking down a jicama or two. The point is that they are so good to eat, and so different to most other vegetables. Under the worthy brown skin, the flesh is a clean pure white. It tastes, when raw, something like green peas, and has the consistency of a large radish, juicy and crunchy and refreshing.

Practicalities

BUYING

If a choice is to be had, opt for medium-sized jicama – larger ones will have begun to develop a mealier texture, which though not unpleasant is less enticing. They should be firm all over, with a matt brown skin. The skin should be unbroken – cuts or bruises suggest that rot may have set in.

In the vegetable drawer of the fridge, a jicama will last for up to a week, even when cut (cover the cut edge with clingfilm to prevent drying out). To use, you need do no more than cut out a chunk, pare off the fibrous skin, and slice or cube the white flesh.

COOKING

Raw jicama is a brilliant addition to a summer salad, but my favourite

way to eat it is Mexican style. In other words, dry-fry equal quantities of coriander and cumin seeds, grind to a powder and add cayenne to taste. Arrange the sliced jicama on a plate, squeeze over lime juice and sprinkle with the spice mixture and a little salt, before finishing with a few coriander leaves. That’s it. When they are at their ripest, I add slices of orange-fleshed melon to the jicama, which makes it even more luscious. Batons of raw jicama are an excellent addition to a selection of crudités served with hummus or other creamy dips.

Jicama responds well to stir-frying, too, again on its own with just garlic and ginger to spice it up, or with other vegetables. It needs 3–4 minutes in the wok to soften it partially, without losing the sweet crunchiness entirely.

Kumara (#ulink_fb577b0e-95cb-53ff-97ab-e5b09c39d7f4)

It isn’t too clever to sell two different vegetables by the same name, even when they look virtually identical. However, for many years that is just what has been happening. When I was a child, the sweet potatoes that my mother brought home as an occasional treat were always white fleshed and we just adored them: roasted in their jackets until tender, then eaten slathered with salted butter.

More recently sweet potatoes have turned orange and soggy. In truth it is not a miraculous transformation, just that one (in my opinion slightly inferior) variety has replaced t’other. For a few transitionary years, you had no idea which you were buying, unless you scratched away the skin to inspect the underlying colour. Anyone with the slightest bit of sense would have seen that these vegetables should be called by different names, and at last that seems to have happened, with the happy reintroduction of the white-fleshed sweet potato, a.k.a. the kumara, to this country.

The word ‘kumara’ comes from the Maori name for the white-fleshed Ipomoea batatas. They are, as you might well infer from this, extremely popular in New Zealand, and indeed in many places around the Pacific. Their country of origin is thought to be Mexico, where roast kumara are sold by street vendors, to be anointed with condensed milk and eaten as a pudding rather than a vegetable. Try it some time and see how good it is.

Kumara is also the sweet potato used widely in the Caribbean for making pies and dumplings. The orange-fleshed sweet potato is not a good substitute here, as the flesh is too watery and lacks the necessary starch to bind ingredients together.

So the point that I’m trying to make is this: kumara are downright gorgeous and you really should try them if you haven’t already. They are still not exactly commonplace but at least one of the larger supermarket chains is importing them regularly, and you may well find them in Caribbean food stores. Go search and you will be well rewarded.

Practicalities

BUYING

If you have the choice, pick out kumara that are on the larger side, with firm, smooth, dark pink-brown skin. Bruises and soft patches, as always, warn you to steer clear. Cut ends will be a dirty greyish colour, but don’t let this bother you – it’s just a spot of oxidisation, not a sign of something disturbing.

Kumara like to be kept in a cool, airy, dark spot, which is not the fridge. Over-chilled kumara develop a tougher centre, at least that’s what producers say. In practice, I’ve found that a day or two in the fridge doesn’t make any noticeable difference to the texture once cooked, which is handy if you don’t happen to have a cool, airy, dark spot to hand. Better the fridge, I find, than a warm kitchen where they are likely to start sprouting.

Longer term storage (they should keep nicely for up to a fortnight) and you really ought to treat them as they prefer – try wrapping them individually in a couple of sheets of newspaper to exclude light and absorb any humidity in the air.

COOKING

In terms of preparation, remarkably little is required. Give them a rinse, trim off discoloured ends and voilà, one kumara ready for the pot.

Or the oven. Which is exactly where you should start if you have never eaten kumara before. Just don’t stall there, as many people do. Yes, baked kumara are delicious, but that’s first base. You bake them just as if they were ordinary potatoes, in other words, prick the skin and then put them straight into the oven at somewhere around 180–200°C/350–400°F/Gas 4–6. Size will dictate how long they take to cook, but think in the region of 45–60 minutes. Split them open and serve with salted butter, or flaked Parmesan or Cheddar, or a great big dollop of Greek-style yoghurt. Remember that if you are eating them with the main course, you will need to partner them with something salty – I find that they are rather good with bacon, or even with tapenade. Excellent, too, with sausages.

Americans and New Zealanders like to surmount their baked kumara with other sweet things like pineapple, grated apple or dates (hmmm), or drizzle orange juice over them, which makes far more sense to me.

So, once you’ve done the oven experience, it’s time to move on. Kumara can be cooked in most of the ways that suit potatoes, i.e. sautéed, chipped, roast, mashed or boiled (a bit dull, frankly). Additionally, kumara can even be eaten raw, or transformed into pudding. I’ve tried it raw, grated into a salad. It’s okay, but not something to write home about. Pudding, on the other hand, is a natural end for the chestnutty kumara. Think that’s odd? Just try making a kumara fool (see recipes) and then tell me that it’s not pretty impressive.

PARTNERS

In recent days, I’ve sautéed cubes of kumara with diced spicy chorizo, which was very successful, and then taken more sautéed kumara and tossed it with rocket and feta and a vigorous lime juice, chilli and sunflower oil dressing to serve as a first course. Mashed kumara are good on their own, seasoned fully to balance the sweetness, or speckled with finely chopped spring onion or coriander. I rather fancy a smoked haddock fish cake held together with cooked kumara (slightly more smoked haddock than kumara, I think), though I haven’t tried it yet.

Also good, and I say this from experience, is a kumara cake – just substitute grated kumara for the carrot in the recipe on page 28. Fantastic.

SEE ALSO SWEET POTATOES (PAGE 91).

Smoky Parmesan roasted kumara cubes

Just damn gorgeous, these are. They’re wolfed down by one and all whenever I make them. There is something utterly irresistible about the combination of sweet kumara with a salty, crisp cheesy crust and a hint of hot smoke from the Spanish pimentón. They probably should go with something (a real burger, perhaps, or roast pheasant) but you might just make them as a snack when the right moment comes.

Serves 6

600g (1 lb 5oz) kumara

30g (1 oz) Parmesan, freshly grated

1 heaped teaspoon Spanish smoked paprika (pimentón)

3 tablespoons olive oil

salt