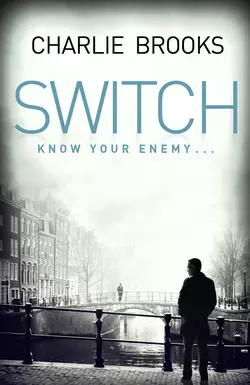

Switch

Charlie Brooks

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Шпионские детективы

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 463.36 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Introducing Max Ward, a modern spy in a dangerous world.Know your enemy…Spared certain expulsion by a faceless puppet-master, MI6 spook Max Ward is happy riding an analyst’s desk at the British Embassy in The Hague and seeing his married lover whenever their schedules allow. Then, out of nowhere, the favour is called in. The same puppeteer finally breaks cover. He’s been watching Max since before he was recruited and now he wants him to face down an enemy Max knows only too well. An enemy both of them have good reason to pursue, and even better reason to leave well alone.Max’s carefully-ordered world is turned upside down as a mission with no escape routes forces him to confront everything he’s forgotten and everyone he’s betrayed. A mission that will finally force him to make a deal with the devil himself.Max Ward is a modern spy in a dangerous world. A world where counter intelligence, drug cartels and global terrorism intersect. A world where the beauty of an Old Master painting hides a deadly game of deal, double cross and revenge.