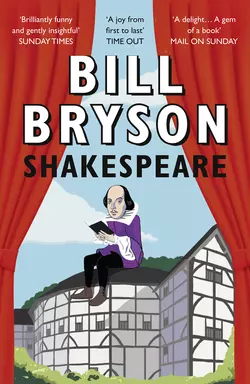

Shakespeare

Билл Брайсон

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 307.01 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: From bestselling author Bill Bryson comes this compelling and concise biography of William Shakespeare, our greatest dramatist and poet.Examining centuries of myths, half-truths and downright lies, Bill Bryson makes sense of the man behind the masterpieces. As he leads us through the crowded streets of Elizabethan England, he brings to life the places and characters that inspired Shakespeare’s work, with his trademark wit and accessibility. Along the way he delights in the inventiveness of Shakespeare’s language, which has given us so many of the indispensable words and phrases we use today, and celebrates the Bard’s legacy to our literature, culture and history.Drawing together information from a vast array of sources, this is a masterful account of the life and works of William Shakespeare, one of the most famous and most enigmatic people ever to have lived – not to mention a classic piece of Bill Bryson, author of ‘A Short History of Nearly Everything’ and ‘Notes from a Small Island’.