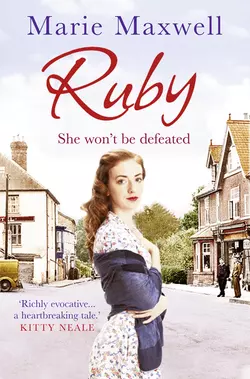

Ruby

Marie Maxwell

As a former evacuee, feisty Ruby is forced to fend for herself when she returns to her family in London.Set in the aftermath of WW2, this gripping saga is richly evocative of the period and shows the true grit of our heroine Ruby.After having lived peacefully in Cambridgeshire as an evacuee, 15-year-old Ruby Blakeley is bought back to reality when her brutish brother Ray comes to take her to the East London suburb of Walthamstow.Far from being welcomed back with open arms, she finds herself being treated as a drudge by her widowed mother and subject to a tirade of taunts from her two brothers.Things get worse when she becomes pregnant. Deciding her baby is better off without her, she runs away from home and gives her child away. Bereft, Ruby makes a new start for herself in Southend, but finds she can’t escape her past.

RUBY

Marie Maxwell

This is for Riley, my gorgeous grandson. His first dedication! xxx

I’d also like to pay a special tribute to the fabulous author and friend Penny Jordan/Annie Groves who died on New Year’s Eve 2011. RIP Penny, you’ll be sadly missed.

Table of Contents

Cover (#uaa72c2b3-bddc-53c2-b341-db0fa002149d)

Title Page (#ua6e9d50f-48a4-5b6f-a88b-114764a4fac4)

Dedication (#u0cdee42a-fa16-5511-bafe-ff176ec8e1ac)

Prologue (#u096ff19e-4f24-5580-a726-ffab1da51cf9)

Part One (#u20a5c2b0-097a-5532-b8f2-aef65b9dc44a)

Chapter One (#u710c621a-e582-5ded-961b-bd925cd1d184)

Chapter Two (#ue19d1270-8b25-5ce1-8ec5-14f9763d9425)

Chapter Three (#ube4f2869-6cea-57a3-bc1c-1c8b90c7c42e)

Chapter Four (#u89abf080-ecad-55c4-adfc-e2f7744de7c6)

Chapter Five (#u3bd41b9c-5742-5851-a7f2-f77e9b7f6a51)

Chapter Six (#uc7c9fdfb-f02e-594b-8805-606cb5f4f9aa)

Chapter Seven (#u0c50f93e-6c73-52ac-8b02-85eada7d344b)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue

Southend Hospital, 1952

‘Someone give me something … I’m in such pain … I can’t breathe,’ the woman on the trolley groaned. Her head rolled back and forth and she clutched fiercely at her chest. ‘I can’t breathe, help me …’ As she spoke, all her strength seemed to float way from her body and she could feel herself being pulled towards unconsciousness. She tried to turn onto her side to curl up into a comforting ball but hands reached out to stop her and hold her flat on her back.

Her mind confused by the ever-increasing waves of pain, she was losing track of where she was. All she knew was that she was suffering the worst pain she had ever felt in her life. She felt as if her lungs were on fire. She could hear voices all around her but she was finding it hard to focus. An atmosphere of urgency pervaded, but the words she could hear made no sense.

She kept drifting between pain and oblivion: floating away peacefully to another place and then being pulled back with the fierceness of the pain.

Then the voices became louder and more urgent, and she felt herself being moved quickly. Bright lights flashed overhead, wheels rattled loudly underneath her and doors slammed behind her. Almost as soon as the journey had started, so it stopped, and people she didn’t recognise grouped around her, touching her, pulling at her clothes. Then there was a pain in her hand, a mask over her face, and she was drifting away again. She just had time to wonder if she was dying, if that was it for her life – if that was all it had been about – before oblivion took her over and she succumbed to the anaesthetic.

‘Time to wake up now,’ a disembodied voice said. ‘Your operation is over and we need to see you awake.’

She tried to shake herself awake but it was hard.

‘Don’t move. You’ve got dressings on your chest and your arm is in plaster. Just open your eyes so we know you’re out of the anaesthetic and then you can go back to sleep.’

She forced her eyes open and focused on the nurse standing beside the bed.

‘What happened?’ The words came out slowly past her swollen tongue.

‘You’ve had surgery. The doctor will talk to you about it later once you’re transferred from post-op.’

As she watched the ramrod-straight back of the nurse walking away, the memory of some of it started to come back to her. It was all disjointed in her head: the sudden crippling pain in her ribs that made breathing agony; the feeling that her chest had exploded; tumbling down the stairs and cracking her head; crawling along the hall to the open front door and then out onto the path looking for help. And then she remembered the fear …

‘What happened to me?’ she whispered, her chest hurting with every breath. ‘Nurse? Nurse … ?’

By then the nurse was tending to a patient across the other side of the post-operative ward. She looked over her shoulder. ‘Sshh, you’re in recovery,’ she said in a loud whisper. ‘Don’t disturb the other patients now. Go back to sleep and doctor will talk to you soon.’

‘Why am I here?’

‘You’ve had an operation. Stop shouting.’

‘Operation for what?’ Her voice was hoarse and her tongue felt as if it was filling her mouth so that she struggled to get the words out.

‘I told you, sshh. I really can’t tell you anything. Doctor has to talk to you and he will, later. He’s talking to your fiancé at the moment.’

‘To who?’ She tried to clear her head. There was an image she was trying to catch hold of but it wouldn’t stop long enough for her to focus on it.

‘I’m sorry but there are seriously ill patients over here I have to look after, so stop the talking and rest,’ the nurse snapped impatiently in a tone that proved tolerance obviously wasn’t her forte in the middle of a busy night shift.

She closed her eyes in despair and let her head fall back onto the skinny pillow that had been placed under her head, but even that hurt. She reached up and touched her face, then had another flash of recall. She struggled to sit up.

‘Someone tell me what’s happened. I can’t remember …’

‘Stop this, you’re disturbing everyone.’

Instead of the recall of events she was searching for, a wave of terror engulfed her and she started screaming, louder than she had ever screamed in her life, and the pain in her chest erupted.

‘Tell me, tell me what’s going on! I’m scared, I can’t remember …’

This frantic call for help was answered with a dose of sedative that took her away from it all again.

Two men stood facing each other in the corridor. The older was dressed in a green hospital gown and short rubber boots with a surgical mask hanging down around his neck; the younger was wearing dark brown casual slacks and an open-necked shirt, a tweed sports jacket slung from one finger over his shoulder.

‘Your fiancée has three broken ribs and one of these pierced her left lung. It was this that necessitated the emergency surgery. She’s going to be in a lot of pain for a while but we can explain the implications of that to her later when we talk about her other injuries.’

‘Will she be all right?’

‘Well, we hope so. It’s fair to say she could easily have died from the lung injury but we’ve done our best to put her back together,’ the doctor said, a hint of contempt in his voice. ‘At the moment she’s as well as can be expected. First the fall with its accompanying injuries, possibly concussion, a head wound, a fractured arm, assorted cuts and bruises, a punctured lung and then the emergency surgery …’ he stopped to take breath. ‘She’s been through a lot but she’s stable and will be taken up to the ward later. We’ve had to sedate her again, she’s so distressed by the, er, accident.’ He made firm eye contact with the younger man. ‘Tell me again how it happened?’

‘I told you,’ the man sighed as if this was really boring him, ‘I don’t know what happened. I wasn’t there. No one was there. I arrived at the same time as the ambulance. I think a neighbour telephoned for it. He heard some sort of kerfuffle going on. Probably her falling down the stairs. She’s so clumsy with those big feet of hers …’ He smiled as he shrugged dismissively. ‘I don’t even know what she was doing there on her own, to be honest.’

‘I see. But we are very puzzled by the bruises on her neck.’

‘They’d be from when she fell down the stairs, wouldn’t they?’

‘It’s possible, but unlikely. Anyway, that’s not for me to decide. I just put her back together again.’

‘You’re absolutely right, doctor. That’s not for you to decide.’ The man held out his hand to indicate the end of the conversation.

‘I suggest you go home now,’ the doctor said. ‘You won’t be able to see your fiancée until tomorrow evening during visiting hours. Check at the reception desk for the hours. I don’t know which ward she’s going to be taken to. Will you be contacting her family?’

‘She doesn’t have any family.’

‘I see …’

The doctor’s tone was cold and he didn’t take the proffered hand. He simply turned sharply and walked back through the doors he’d emerged from a couple of minutes before.

A look of anger flashed across the other man’s face, and for a moment it looked as though he would follow the doctor, but instead he breathed deeply several times before turning round and heading down the corridor in the direction of the main exit. Once outside he sat on the wall, taking more deep breaths before lighting a cigarette and thinking about everything that had happened. He wanted to get it all straight in his head, just in case. After he’d ground the butt into the flowerbed he walked down the footpath and swung open the door to the phone box that stood at the main gate.

He fumbled in his pocket for coppers and then made his call. ‘Hello? It’s me. I know it’s late – or early, depending on how you look at it.’ As he spoke he checked his hair in the mirror that was fixed on the wall above the phone and then pulled a comb out of his back pocket. ‘I’ve had a strange old night but everything’s OK now and I’m dying for a decent cup of coffee … among other things!’

He smiled at himself in the mirror as he put the phone back into its cradle, then he flicked the comb through his hair, slipped on his jacket and pushed the door open. He held the door back for the elderly woman waiting patiently outside.

‘Thank you kindly young man,’ she said. ‘Have you just come out of the hospital?’

‘I have. My fiancée’s had an accident.’

‘Ooh dear, I hope she’s OK.’

‘Oh, nothing serious. Just a bit of a tumble and a few bruises. I’ve told her to lay off the gin in future.’ He grinned.

Shrugging his jacket straight, he pulled at his collar and walked away from the hospital where his fiancée lay battered and bruised.

Part One

One

Melton, Cambridgeshire, 1945

‘Here comes the train. Mummy, Mummy, I can hear it, I can hear it!’ As the small boy’s shriek pierced through the general chatter on the crowded railway platform the conversations started to fade away and the train appeared around the bend in the track lumbering noisily towards the station. Children jumped up and down excitedly at the sight and sound of the huge steam engine, and adults automatically reached down to pick up their bags and baggage.

Ruby Blakeley wasn’t feeling in the least bit excited as she pushed her own two small suitcases nearer the edge of the platform with her feet and then looked at the woman who was holding tightly onto her hand. She was feeling terrified.

‘It’s the train …’ the girl sighed sadly. The woman pulled the teenager in towards her and hugged her tightly.

‘Oh, Ruby, I’ve been dreading this moment. Uncle George and I are both going to miss you so much. I still can’t believe you’re leaving us.’

‘I’m going to miss you too, Aunty Babs. I don’t want to go back, but I have to. There’s no other way.’

‘I wish there was something we could do to persuade your family to let you stay. We’d love you to work in the surgery with us. We need the help, and you could send money to your mother and support her that way.’

Ruby let herself be hugged for a few seconds before blinking hard and pulling back. More than anything she wanted to turn round and go back to the comfortable, loving home she had become accustomed to over the past few years.

‘I know, but Mum said no. She said I have to go back. If I don’t go she’ll send Ray to collect me and you’ve seen what he’s like. I suppose it is hard for Mum. Ray said I have to go and help her, what with Dad not coming back and Nan being there and everything …’

‘Yes, dear, I know what Ray said, but having met him I think you and I both know he likes to exaggerate a little.’ The older woman went on quickly, ‘Listen to me, Ruby. I know you have to go but I want you to remember that we’re always here for you. Any time you need anything, or you just want to come and see us, we’ll send you the train fare,’ she took hold of the girl’s arm, ‘or if things change and you want to come back and live here again. We’ll keep your room, even if it’s just for a holiday with us. This will always be your home.’

‘Will you really? I’d like that,’ Ruby said with a hopeful smile.

‘Of course we will. Now don’t you forget to keep in touch. We both think of you as our daughter. I never expected that to happen the day we took you into our home, but now …’ Barbara Wheaton paused mid-sentence as her eyes welled up. She touched Ruby’s cheek with her gloved hand. ‘Now it’s as if you were always with us, part of our family.’

‘Thank you. I’ll write, I promise. I’m going to miss you both so much.’

‘And I’ll write. Now you’re sure you’ve got the paper on which Uncle George wrote everything down for you? We don’t want you to get lost in London, and you mind who you talk to on the train.’ She smiled and shook her head. ‘I do wish you’d let us drive you back.’

‘I’ll be careful, I’ve got the paper in my bag and I’ll be fine. Mum is going to meet me at the bus stop when I get to Walthamstow.’

At fifteen Ruby was slender and coltishly leggy with green eyes and dark red curls not quite tucked away under the brim of a grey beret, which matched her knee-length tailored coat. Her ‘aunt’ was taller in her high heels, her hair pinned into an elegant chignon, and her face subtly made up, but the women were of similar colouring and bearing, and, standing side by side, they looked just like the mother and daughter Ruby had often wished they were. It had been nice to be the cosseted only child in a loving home instead of the ignored youngest in a crowded unhappy house, but now she had to go back to her family.

Amid billows of smoky steam the train bound for London lumbered to a standstill and, after one more hug, Ruby clambered aboard with her cases and sat down in a window seat. Forcing herself to be detached she smiled and waved through the steamed-up glass as the train started to chug forward while Babs Wheaton stood perfectly still on the narrow platform dabbing gently at her eyes with one hand and waving with the other.

Just outside the station Ruby could see Derek Yardley, the Wheatons’ driver, watching through the fence. As the train moved away she saw him raise a hand and wave. To all intents and purposes it was a friendly wave but she could see his stone-cold eyes staring directly at her. She hated him with a passion. He was the one person she certainly wouldn’t miss, and she knew without doubt that he was pleased to see the back of her, too.

Ruby remained dry-eyed and outwardly unemotional but inside she felt sick and angry at the thought both of what she was leaving behind and of what she was going back to.

It just wasn’t fair.

Five years previously, amid many tears and tantrums, the ten-year-old Ruby had fought desperately against being evacuated from her home and family in wartime East London to the safety of a sleepy village in the Cambridgeshire countryside. Just the thought of going had been terrifying to the young girl, who had never been away from home for even a night. But once she had adjusted to the change, she had settled in and her time with Babs and George Wheaton had turned into the happiest of her life. She had stayed on long after the other evacuees had returned home.

But now the war was over and, despite pleading for Ruby to be allowed to stay indefinitely, her host family had been told that their evacuee had to return to her real family.

Ruby’s eldest brother, Ray, had visited a few weeks previously and stated in no uncertain terms that it was way past time for the only daughter to do her bit for the cash-strapped family. Her mother wasn’t prepared to agree to her staying away any longer.

Leaning back in her seat, Ruby closed her eyes. She was dreading it.

After five years living with the very middle-class country GP and his wife, who had picked her randomly from the crocodile of scared evacuees transported to the village school playground, Ruby had changed dramatically. She had morphed from a frightened shadow of a child into a self-confident and popular young woman with a good brain and a quick wit, although there was still a certain stubbornness about her that could surface quickly if she was crossed.

She had also grown accustomed to being loved and cared for, even spoiled, by her childless host parents.

It was all so different from her other home, a small terraced house in Walthamstow where she had lived for the first ten years of her life; the home where she had been brought up, the youngest child with three brothers who had constantly overshadowed her early years with their boisterous masculinity and smothering overprotectiveness; the home where her bedroom was the tiny boxroom and her role was to be seen and not heard, especially by her father. Ruby thought that her mother probably loved her in her own way, but she didn’t have any time for her, and Ruby’s enduring memory of those first ten years was of constant loneliness and anxiety. She hadn’t actually been unhappy at the time because she didn’t know any different, but now she knew how childhood could and should be.

Sitting in the carriage, carefully avoiding any eye contact with the other passengers, Ruby could feel that the old anxiousness returning, but she resisted the urge to nibble around the edges of her nails as she had when she was a child.

There was something niggling her, a thought that she couldn’t quite get hold of. She could see how her mother would be run ragged and struggling to cope with a house full of adults, but she couldn’t understand why anyone in her position would fight to add an extra person into the mix, an extra mouth to feed. It simply didn’t make any sense.

When Ray had unexpectedly turned up on the doorstep a few weeks previously to order her home, Ruby had been mortified. The gawky schoolboy she remembered had turned into a sneering young man. Ray Blakeley had gone from rowdy boy to ill-mannered lout, the kind of person Babs and George had always encouraged her to avoid at all costs.

‘Ruby? There’s someone here to see you. I’ve sent him round to the front door,’ George had shouted through the hatch in the door that joined his village surgery to the house.

Ruby had run down the stairs from her bedroom expecting to see one of her friends in the lobby, but instead there was a young man. She looked at him curiously for a moment and then realised.

‘Ray? What are you doing here?’ She couldn’t keep the shock out of her voice.

‘Now that’s not a nice way to talk to your big brother, is it, Rubes?’ he grinned. ‘No hello? No long time no see? No nothing at all?’ With both hands in his pockets he looked her up and down critically and shook his head. ‘I dunno, look at you done up like a dog’s dinner. Looks like I got here just in time before you get any more stupid ideas above your station. Mum told me you’re all la-di-dah now.’

‘I’ve just got back from the town; I was just going to get changed,’ she countered defensively.

‘Just got back from the town,’ he mimicked her voice and enunciation with a wide grin. ‘Just got back from the town. Posh talk there girl.’

As a bright scarlet blush crept up her face, Ruby could feel herself shrivelling inside, reverting back to the trampled-over child she had been before her evacuation. But then she noticed Babs standing in the kitchen doorway, observing quietly, and her confidence returned.

‘Aunty Babs, this is my oldest brother, Ray. He’s come to see me,’ Ruby said brightly, looking for a distraction.

Ray glanced dismissively at the woman before turning his attention back to Ruby.

‘Oh, no, you’ve got it wrong, Rubes. I haven’t come to see you, I’ve come to take you back home. Now.’

‘But I don’t want to go back.’ As soon as the words were out she realised she’d made a mistake. ‘I mean, I’m not ready. You can’t just turn up without warning and expect me to go with you. I’ve got school and all sorts of things …’

‘No choice there, Rubes darling. School’s done for you, and Mum wants you back home, what with the old man more than likely dead … please God.’ He paused and grinned before continuing, ‘But you know that. Enough mucking around – she’s writ often enough – so now she’s asked me to come and get you; drag you, if I have to. Time to stop being all duchesslike and get back to where you belong.’

Babs stepped forward quickly, held her hand out and smiled.

‘I’m pleased to meet you, Ray. I’ve heard so much about you. Dr Wheaton and I were so sorry to hear about your father. I have sent my condolences to your mother.’ Her smile widened in welcome. ‘But you’ve had a long journey and you must be famished. Come through to the kitchen and I’ll make you some tea and find you something to eat. If I’d known you were coming I’d have had a meal waiting.’

As he ignored the proffered hand it was obvious Ray was confused by the welcome, and he stared suspiciously at this seemingly genial woman. But when Babs and Ray locked eyes for several moments Ruby could see that the gauntlet was down, although she wasn’t sure who had thrown it.

‘OK, must admit I’m bloody starving; but then we have to get back.’ He looked back to his sister. ‘You go and get your stuff packed as quick as you can while I have a feed. I can’t muck around all day. And I hope you’ve got your train fare else you’ll have to run behind.’ He laughed as he held his hand out palm up towards Babs and rubbed thumb and forefinger together theatrically. ‘Oh, and we expect a bit of payback for keeping our Rube here for so long …’

Ruby could feel crushing embarrassment taking over her whole body. Ray was behaving like a complete lout and she couldn’t figure out why. He’d always been a bully but she didn’t remember him being quite so bad-mannered.

‘Oh dear, Ray, I’m really sorry but I don’t think Ruby should travel today. She’s been a bit under the weather the last few days.’ Babs Wheaton’s expression was suitably apologetic. ‘There’s a lot of mumps going about the village. We’re not sure if Ruby’s got it yet, but it can be really bad for young men. I wouldn’t like to see you or your brothers go down with it. The side effects could be really nasty …’

As he thought about it Ray Blakeley screwed his eyes up and stared intently at his sister’s neck. ‘She looks all right to me, and she’s just come back from town.’ Again he put on the silly voice. ‘She wouldn’t be out and about if she were that bloody sick …’

Babs reached forward and placed her palm on Ruby’s forehead.

‘Your sister’s such a good girl, she’s putting on a brave face and pretending to be fine, but we’re worried the mumps may be in the incubation period. We’re not sure yet.’ Again Babs smiled. ‘But we’ll soon see. Now let’s go and see what I can conjure up to feed you, but don’t sit too close to Ruby. Just in case.’

Her words hung in the air as Babs led the way through into the kitchen and motioned for the brother and sister to sit at opposite ends of the vast farmhouse table. As he looked around the homely room with a slight sneer on his face, Ruby studied Ray and tried to work out whether he was being deliberately uncouth for effect.

With his even features, dark brown hair and a jaunty moustache, he looked older than nineteen. His clothes were clean, his shoes polished and he looked presentable enough – smart, even – but he had an arrogant swagger in his walk and more than a hint of aggression in the angry eyes that stared out from behind horn-rimmed spectacles. As she watched and listened, Ruby decided that, despite his being her brother, she really didn’t like Ray Blakeley one bit.

As Ruby surreptitiously studied him from the other end of the table, Babs quickly made some thick cheese and pickle sandwiches and put a plate in front of him along with a chunk of cold apple pie, a big mug of tea and a white napkin tucked inside a ring.

Ruby watched in fascination as, ignoring the napkin, Ray stuffed the food in his mouth, washing each mouthful down with a swig of tea and dribbling as he talked with his mouth full. Within a few minutes the plates were clean and he looked at Babs, leaned back in his chair, wiped his mouth with the back of his hand and belched. ‘Another cuppa’ll really go down a treat, missus.’

It was at that moment that Ruby, overwhelmed with shame, knew he was being deliberately uncouth; that he was being provocative. She also knew that her mother would be equally horrified because none of them had been brought up to speak like that to anyone, let alone an adult, or to behave like that at the table.

As she stared at her brother in disgust a door next to the walk-in pantry opened and Dr Wheaton came through from his surgery at the other side of the rambling old house. His wheelchair clunked as he expertly wheeled himself across the stone-flagged kitchen floor and manoeuvred himself up to the table.

‘Ray, this is Uncle George.’

‘What happened to you, then? War wounds?’

‘No. Polio. When I was a child.’

‘Oh right. So as Ma says, this contraption is the reason you want our Rubes to stay here, so she can look after you? She says all the other kids are already home and you two want her as your skivvy.’

As Ruby froze, so George smiled. ‘No. I don’t need looking after. Ruby’s still here because she wanted to finish her schooling here. She’s very clever and doing well. We sent her school reports to your mother.’

‘Yeah, well, it’s not reports Ma needs, it’s another pair of hands to help her out, and that’s what Rubes has got, so off we go.’

Ruby looked from one to another before saying, to try to calm Ray, ‘Uncle George is a doctor.’

But Ray just looked at her as if she were mad. ‘I know that, you daft bint, but I’ve never seen a doctor in one of those. Who’d have thought it?’

‘And I’m going to train to be a nurse when I’m old enough,’ Ruby added.

‘Course you are, Rubes, and I bet that’s the doc’s idea: a nurse in the house to save him a few bob. Shrewd, eh?’

Ruby had to sit through another hour of embarrassment before Ray, having conceded that she could stay another couple of weeks until she was definitely confirmed fit, finally left, informing her he’d be back for her if she wasn’t home within the month.

Two

As Ruby was deep in thought, and going where she didn’t want to go, the train journey into London was over in a flash and, following George Wheaton’s instructions to the letter, Ruby caught the bus to the stop nearest to her road in Walthamstow. She looked around hopefully for her mother, but after a twenty-minute wait in the autumn evening chill she gave up and started walking.

The Wheatons had wanted to drive her back home but, after Ray’s disrespectful behaviour, Ruby wanted to keep her two lives apart so she had determinedly refused. She had insisted that she was old enough to make the trip alone, but as she trudged along the streets and the two suitcases got heavier and heavier she regretted her decision. She kept picking them up and putting them down and changing hands, even though they were the same weight. When she was halfway there she dumped them on the pavement and sat down on one of them to catch her breath.

She looked around at the once-familiar surroundings that she had all but forgotten about when she was living safely in the open spaces of rural Cambridgeshire. Terraced houses with tiny front gardens edged both sides of the road, and the smell of coal smoke hung heavy in the air. Before her evacuation the area had simply been home, but now she viewed it objectively and it felt claustrophobic and grubby.

Amid the familiarity of the streets remnants of the war stood out. There were pockets of emptiness and rubble where houses and shops had once stood, and as she looked across the road at the bombed-out remains of two adjoining houses she thought about who might have been inside when the bomb fell.

Suddenly the recently ended war was real and the loss of life she’d heard about was on her own doorstep.

As she clenched and unclenched her aching hands and tried not to cry, a young man she had vaguely noticed walking along on the other side of the road crossed over and stopped beside her.

‘They look far too heavy for a little thing like you to be carrying; here, let me help you. Where are you going?’

‘To Elsmere Road, the far end, but it’s OK, I can manage perfectly well on my own. I’m just giving my hands a rest,’ she snapped defensively.

‘That’s just past where I’m going so it’s daft for you to carry them on your own. When you’ve got your wind back we’ll get going, but I’m not carrying your handbag.’

The young man’s expression was friendly and his smile wide as he waited for her to stand up again. Once she was on her feet he quickly picked up the cases and loped easily along the street, leaving Ruby almost running to keep up. In no time they were by the familiar front gate to the Blakeley family home.

‘Here, this is the house.’

The man put the cases down on the pavement.

‘Thank you,’ Ruby said, looking up through her eyelashes into a pair of navy-blue eyes. Under his intense gaze she felt strangely shy.

‘You didn’t tell me your name,’ he said.

‘I know I didn’t,’ she replied.

With his eyes still fixed on her, the young man held his hand out. As she took it he gripped firmly and, as he held on slightly longer than was necessary, Ruby felt a strange tightening in her throat that she couldn’t identify.

‘Well, I’m Johnnie, I’m from down the street. I live here; Walthamstow born and bred. Are you visiting?’ he asked, still holding on to her hand.

‘No, Johnnie-from-down-the-street,’ she smiled as she withdrew her hand from his. ‘I live here as well. I’ve been in evacuation for five years and I’ve just come back. It all seems strange, though. I know where I am but it doesn’t feel like home any more. It’s all different.’

‘That was the war …’ He paused for a moment and then raised his eyes upwards. ‘Ah! I was a bit slow there! Of course you’re Ruby; Ruby Blakeley, the missing sister who’s been having such a time of it she didn’t want to come home again. And none of your brothers came to meet you? They should be ashamed of themselves, leaving you to drag your own cases through the streets.’ Johnnie Riordan shook his head slowly, his disapproval all too obvious.

‘I wasn’t dragging them, I was carrying them,’ Ruby frowned. ‘How did you know all that about me?’

‘Your brother Ray has a very loose mouth; blabs all the time. Lucky he missed call-up; we’d have lost the war after he’d given chapter and verse to Hitler’s spies.’

Ruby tried not to laugh. ‘And you? Why didn’t you go and fight?’

‘Just missed out, but I’ve been doing my bit in other ways.’ He winked.

‘That’s what they all say … So how do you know my brothers?’ she asked curiously.

‘Ah! That’s for me to know and you to find out.’ He winked again, and another very strange feeling fluttered gently through her chest. ‘And I’m sure you will very soon, just as soon as you tell your brothers you met me. I’ll be seeing you then, Ruby of the red hair!’

With a wide grin, a tip of his hat and a flamboyant backward wave the man strutted down the road in the direction from which they’d come. Ruby watched as he casually kicked a ball back to a group of children playing in the middle of the road and then disappeared into a gate halfway down the street.

She guessed he was older than she – he certainly looked it – maybe even older than her brothers, and he had an edge of danger about him that excited her momentarily; but she knew it wasn’t the time to be thinking about handsome young men.

She was home, but all she wanted to do was turn and head back to the security of Melton and to the Wheatons, the substitute parents who had cared for her and loved her as their own.

She pulled back the wooden gate, took a couple of steps along the short concrete path and, after banging sharply on the door knocker, waited impatiently for what seemed an age before the door opened.

‘Hello, Mum,’ she smiled.

The woman looked at her for a moment before registering that this was her own daughter.

‘Ruby! Hello, dear, you’re early. I was just going to walk down to the bus stop to meet you, but you’re back here already.’

‘I was right on time. I waited for you for ages …’

‘Not to worry. I had so much to do I must have got behind. But you’re here now so in you come.’

The woman who had opened the door was small and round with wavy faded red hair pulled back from her face and tucked up in an old voile headscarf that was tied on top of her head. She was wearing an enveloping flowery apron and neatly darned woollen slippers.

Her appearance told Ruby that there was no way she had been getting ready to go out, and she felt hurt that the mother who had stated how desperate she was to have her daughter back home couldn’t even be bothered to walk down the road and meet her off the bus after such a long journey.

Sarah Blakeley held the door right back, then turned and shouted. ‘Arthur? Your sister’s here. Come and take her cases to her room.’ She turned back to her daughter. ‘Ruby, you go back out and shut the gate before those little urchins across the street start swinging on it again. I’m just sorting your brothers’ tea and then we’ll have ours after with Nan.’

Her eyes widened as she looked at her daughter properly for the first time. ‘You’ve grown, Rube – I nearly didn’t recognise you – and you look very glamorous, but a bit too old for your age. Did that Babs woman give those clothes to you?’

‘Yes, she made me lots of clothes and altered some of hers for me.’

‘Not really suitable for a fourteen-year-old …’

‘I’m fifteen, soon be sixteen,’ Ruby sighed.

‘Still not quite right, though. I’ll try them on later. I haven’t had anything new for years.’

And that was the total of her welcome home from her mother after five years away.

Ruby stood for a moment on the threshold and stared straight ahead at the faded wallpaper in the narrow hallway and the staircase that disappeared off into claustrophobic darkness. She didn’t even want to go in, let alone live there again. She wanted to run; but then she heard her grandmother.

‘Is that you home, Ruby?’ a voice called out. ‘Come and say hello to your old nan.’

‘Coming, Nan. Just going back to shut the gate.’

As her mother turned and walked back to the kitchen, Ruby’s brother Arthur bounded down the hall past her and grinned. ‘Hello, sis, decided to come home at last? Ray said you’d landed on your feet in that big posh house. He said you’ve gone la-di-dah and we’ve got to knock it out of you now you’re back!’

At seventeen and not much more than a year older than his sister, Arthur had always been closest to Ruby in all ways and she had never taken offence at him the same way she had with her other brothers. He was a lump of a boy who had always had a certain slow innocence and openness in his nature, unlike Ray and Bobbie, who could both be mean and devious when the mood took them. She was pleased to see that, on the surface at least, Arthur seemed the same good-natured lad she remembered and she hoped that Bobbie, the middle brother in both age and temperament, had maybe grown up and away from Ray. Life back home would certainly be easier if her oldest brother was the only unpleasant one in the family.

‘You could try, I suppose, or I could teach you how to be posh as well? It’s not that bad, you know, there’s nothing wrong with good manners.’ She laughed as she put an arm around his waist and hugged him affectionately, much to his embarrassment.

‘Get off,’ he muttered as he pulled away, making her laugh.

‘I’ve really missed you, Arf. You look so grown up now and you’re so tall. It’s a shame you didn’t come to the country, you’d have loved being out in the open. I had a friend Keith who you would have loved playing with. He even had a gun to shoot rabbits and pigeons. It was great fun – even school – and Uncle George and Aunty Babs were so nice to me. I love them so much.’ She paused as she realised exactly what she’d said. ‘But I love you all as well, especially you, and even Ray.’

‘We’re boys. Dad said boys who were evacuated were cowards.’ Arthur bristled and squared his shoulders. ‘Dad said we had to look after ourselves and Mum, and that’s what we did. We weren’t girls …’

‘Weren’t you scared you might get killed with all the bombs?’ Ruby asked curiously, still aware of the bombed-out houses she’d seen.

‘No. We weren’t scared. And now the war’s over and we won! Ray said you weren’t away because of the bombs, he said the posh people wanted you because the bloke’s a cripple and she’s barren. Ray said—’

‘That is such rubbish,’ Ruby interrupted angrily. ‘Lots of different people took in evacuees and some of the hosts were really horrible to them. I was really lucky that I ended up where I was. Especially as no one from here bothered to check if I was OK.’

But Ruby knew that she was wasting her time. Arthur really didn’t understand.

‘Ruby, are you going to come and see me?’ called Nan. Ruby turned away from Arthur and started towards the parlour.

‘I’m just going to see Nan and then I’ll tell you all about it,’ she said.

Arthur picked up the cases and followed close behind her.

‘You’re supposed to be taking them to my room.’

‘I am. Didn’t Mum tell you? You’re going to be sharing with Nan in the parlour. Ray’s got your old room.’

‘You’re joking. I can’t share with Nan. And what about the things I left?’ Ruby turned and looked at her brother in horror.

‘I think Ma got rid. Ray took your room as soon as you went away. Can’t see him coming back in with me and Bobbie now he’s the head of the house, can you?’ Arthur laughed.

‘Why can’t Nan share with Mum?’

‘’Cos of the stairs, you idiot.’

‘Why can’t I share with Mum?’

Arthur laughed. ‘I dunno …’ Pretending to spar, he skipped around and punched his sister hard on the arm, the way he used to when they were children, but now he was physically a man and the punch hurt.

‘Don’t do that, Arthur,’ she snapped at him. ‘Don’t hit me, don’t ever hit me. We’re not children any more. Adults don’t hit each other.’

‘Ooh, get you, Duchess. Ray was right. He said you think you’re better than us now.’

Looking angry and still unaware of his own strength, he pushed at her and she stumbled backwards slightly.

‘Well, I’m definitely better than Ray, I promise you that,’ she snapped back angrily as she struggled to stay on her feet.

The door was open so Ruby turned straight into what used to be the front parlour, where they would all have dinner on high days and holidays, and formal tea when the parish priest visited, but everything that had been in there was gone, including the familiar battered piano that Ruby had loved to try to play.

Instead there were two narrow iron-framed beds with a bedside cabinet each, a wardrobe and a tallboy, which took up half the room, leaving just enough space for a chest of drawers with a jug and bowl atop and her grandmother’s armchair in the small bay of the window. Arthur dumped the cases on the bed nearest the door and went out again without saying another word. Ruby knew she’d hurt his feelings but she was upset herself. She was, however, determined to make it up to him later because she knew he was the only one who she could rely on.

As she looked around all she could see in her mind’s eye was her bedroom back in Cambridgeshire, the large and airy room with a wide comfy bed, a huge walnut wardrobe with drawers underneath, a matching dressing table and a ruby-red chaise longue that Aunty Babs had covered to match the curtains.

It was all hers but she’d had to leave it behind, and now she was standing in a room less than half the size, which she was going to have to share with her incapacitated grandmother. It just wasn’t fair and, try as she may, she couldn’t understand why they had wanted her back to cramp the house even further.

Keeping a determined check on the tears that were threatening at the back of her eyes, she went over to the bay where her grandmother was sitting.

‘Hello, Nan. I’m back and it looks like I’m sharing with you. I’m sorry.’

‘Oh, it’s not your fault, Ruby dear. The war’s meant we all have to make sacrifices, and Sarah was good enough to take me in so I can’t grumble. Now come up close so I can see you; my eyes aren’t what they used to be.’ As Ruby moved closer the woman grabbed her hands and pulled her down. ‘Ooh, you’re a proper young lady, you are now, by the looks of it. Ray said you’d grown up. Now tell me all about it while you unpack. There’s some coat hangers on the side. You’re going have to use the picture rail for now to hang your clothes until I have a sort-out.’

‘I’ll unpack later, Nan, I’m so tired …’

‘All night, dear. Then can you help me through to the back? We can have a cuppa before tea. I don’t eat with the boys – they’re too noisy and there’s not enough room at the table. Me and your ma eat after they’ve all finished and gone out doing whatever it is that young men do nowadays. You’ll be eating with us, I suppose.’

Ruby didn’t answer; she just couldn’t think what to say. She was both horrified and saddened as she looked at the elderly woman with stooped shoulders and cloudy eyes, who was peering up at her expectantly, waiting for an answer. One hand rested atop a wooden walking stick and the other gripped a vast dark grey crocheted shawl around her shoulders.

During the five years she had been away Sarah Blakeley had visited her daughter every other year on her birthday, but as Ruby hadn’t been home at all she hadn’t seen her grandmother in all that time, and she was shocked to see how much she’d aged.

It was on one of the birthday visits that her mother had told her that Nan, already a widow, had been bombed out of her own house in Stepney and come to stay with the family, and after her eyesight had deteriorated there was no way she could live alone. So there she had stayed, despite the overcrowded accommodation.

‘Shall we go through to the back now, Nan? How do you want me to help you?’

‘Just let me take your arm. It’s the rheumatics, they kill me in this weather and make me feel ancient.’ She laughed. ‘Oh, it’s good to have you home. You can help your mother around the house. Those boys are such hard work for her, what with her job and me being no use to her any more.’

‘I’ve not come home to look after the boys, Nan. I’ll help when I can but I’m going to be a nurse. I’m going to get a job and save up to start training when I’m eighteen.’ Ruby smiled down at her grandmother hanging on her arm.

‘Ooh no, Ruby, I don’t think the boys’ll let you do that. Oh no, dear, no.’ The woman’s voice rose sharply and she shook her head so violently Ruby took a couple of steps back. ‘They said you were coming home to look after me and help your mother in the house. That’s why they wanted you home … and they’re a real handful for your poor mother, especially with no father to make them take heed.’

‘I’m not doing that. If I can’t go to school then I’m going to work.’

The old lady pursed her lips and blew out air noisily. ‘I wish it was so, but I don’t think so dear I really don’t …’

Ruby stopped listening as she wondered how to stop Ray from taking over her life now, as Nan had reminded her, their father wasn’t around to control the boys.

Ruby hadn’t seen her father since the day she had been shipped off to Cambridgeshire, but she had rarely given him a thought. Frank Blakeley had always been so distant with her that she might as well not have existed in the family; it was as if she were invisible. He would, however, often rough and tumble fiercely with his sons to teach them to be men, and discipline them harshly for the smallest misdemeanour, his belt being the favoured tool of formal punishment, or his hand around the back of the head for an instant reprimand.

It was usually Ray who was the recipient of the fiercest beatings because he just would not give in. Ruby and Arthur would cower together, staying as quiet as possible when their father was beating Ray into submission, each of them praying for him to apologise and end it, but he rarely would. It meant that afterwards, despite the pain and the silent tears, Ray would be victorious.

Believing that girls were the responsibility of their mothers, Frank had never laid a finger on his daughter; but he had never interacted with her either. The news that he was dead had been a shock and she had felt sad – he was her father after all – but nowhere near as upset as some of the other evacuees had been when they had received similar news during the war. In the years she was in evacuation George Wheaton had been more of a responsible father figure to her than her own father had in the previous ten, and she adored him for it.

‘Mum?’ Ruby said as she helped her grandmother down the step into the back room. ‘Are you there, Mum?’

She had expected her brothers to all be there to welcome her back; for her mother to be waiting for her; but no one seemed to be around.

The room was long and dim, with a single standard lamp alight in the corner; it was dominated by an impressive round table with large bulbous feet, which was covered in a shiny oilskin tablecloth and encircled by six hard-back chairs. The alcoves either side of the chimney breast had built-in dressers, which were filled with assorted crockery, serving dishes and the best sherry glasses. A wooden canteen of cutlery had pride of place on one side, and two large Chinese-style vases, which had previously stood either side of the fireplace in the parlour, on the other.

As her grandmother sat at the table and shuffled herself comfortable, Ruby went through the scullery to the back door, which was wedged open with an old iron pot. She stepped out into the back yard, trying to ignore the outside lavatory, which she knew she would have to get used to using again. Just the thought of it made her feel nauseous.

‘Mum? Where are you?’

‘Out here, Ruby, just getting the washing in. I should have done it hours ago. Can you come and help me?’

‘Nan wants her tea. I said I’d make her a cup of tea while she waits. I thought the boys would be here to say hello.’

‘Well, Nan will just have to wait until I’ve finished this, unless you want to heat it up for her. It’s in the oven with yours. The boys have gone off somewhere like they always do and there’s all this needs doing. Good job it’s been a nice day, but it’s already starting to get damp.’ Her mother looked at her and smiled brightly. ‘Now come over here and I’ll show you whose clothes are whose. The boys don’t like it if their clothes get all mixed up!’

‘The boys, the boys. Don’t you want to know what’s been going on for me? I’ve been away for five years. Five years,’ Ruby said flatly without moving. The washing line was stretched the length of the small back yard, which was part paved and part vegetable garden. A small corrugated roof extended out from the scullery and provided cover for the mangle. At the end, the gate that led out into the back alley was open.

‘Don’t be silly, Ruby, we’ve got plenty of time to catch up on everything now you’re back for good. Back where you belong, not up there with those snobs. Here, hold this for me …’

Still smiling, Sarah pushed a battered laundry basket at her. Looking down, she remarked, ‘Those shoes are a bit too grown up for you. You’re only fifteen and they’ve got a heel …’

‘And they’re too big for you,’ Ruby replied quickly with a smile, aware of the way the conversation was about to go. ‘My feet are huge.’

‘That’s all right,’ her mother replied seriously, still looking at her daughter’s feet. ‘I can stuff paper in the toes.’

Ruby didn’t answer. She didn’t want an argument, but she could see her mother was going to find it hard to accept that Ruby had gone away a child and come back an independent young woman with a mind of her own and ambitions to fulfil.

At that moment, standing in the back yard with a washing basket of clothes in front of her, she knew that she couldn’t stay in Walthamstow. It had been her home when she was a child but now that she had seen a different way of life it was alien to her. She’d tried to do the right thing but she could see that her return had actually been nothing to do with her personally. It was simply a power struggle, with her mother and Ray asserting their position over the Wheatons.

She watched as her mother quickly took the washing off the line and transferred it to the basket Ruby was holding out. She pretended she was listening to her mother’s instruction about whose clothes were whose but she was already mentally composing her letter to George and Babs Wheaton, telling them she wanted to go back.

But even as she was doing it she knew that the letter would be the easy part. Persuading her mother and Ray would be the problem.

Three

Ruby found life back at the Blakeley family home far more difficult to deal with than she had ever expected and, as the weeks passed, it got worse rather than better. She looked after her grandmother, helped around the house and ran errands for her continually overworked and dog-tired mother. She did her duty as she saw it, the duty she had gone home to do, but nothing seemed enough. Alongside that she generally irritated her bombastic brother, Ray, as much as she could, her view being that if she annoyed him enough there wouldn’t be any objections to her leaving and going back to Cambridgeshire.

As the days passed she became increasingly obsessed with getting back to the Wheatons, and it always took several seconds when she woke up in the morning to remember where she was and then for the overwhelming sense of injustice to rise again. But her mother refused point blank to even discuss Ruby’s return to Melton.

‘Mum? I’m off to the High Street,’ Ruby shouted, quickly pulling the front door closed behind her and hotfooting it away from the house. She wanted to escape before she was given an even longer list of things to do and items to try to buy. She resented always having to do the shopping, especially with rationing making it such a chore, but at least it got her out of the house and away from her mother’s ongoing domestic grumblings, and Ray’s tormenting, which was made worse by her middle brother, Bobbie, slavishly agreeing with his every word. Arthur remained her friend as best he could, but his fear of upsetting his oldest brother meant he would always run off and hide rather than get involved.

Ray and Bobbie worked at the same motor repair garage so more often than not they left together in the morning on Ray’s beloved motorbike and arrived home together in the evening expecting their dinner to be waiting for them on the table, their clothes to be washed and ironed and their beds made.

And everything was always done. Their mother made sure of it.

Sarah Blakeley had easily accepted Ray’s declaration of himself as ‘Head of the Family’, and Ruby saw he was turning into a clone of his father, the man he and his brothers had always been petrified of. He carefully shaped his moustache in the same manner, tipped his flat cap at the same angle, and when he shrugged on his late father’s heavy overcoat the resemblance from a distance was perfect.

Ruby couldn’t understand why he would want to be just like the father who had always treated him so harshly but she didn’t comment; she simply observed and wondered why her mother didn’t stand up for the women in the house.

She was deep in thought as she walked and was almost at the bottom of the road when she heard her name being called.

‘Ruby! Ruby! Hang on a minute …’

She hesitated but didn’t turn round; without looking she knew that it was Johnnie from down the street, the man who’d carried her bags and caught her eye; the man she’d only seen in passing since that day, but who she had thought about and also heard much about.

‘Ruby!’ he shouted again. ‘Wait a minute and I’ll walk with you, Ruby Red.’

This time she stopped and waited with a smile for him to catch her up.

As he drew alongside he looked at her appreciatively and she was pleased she’d come back from the Wheatons’ with a decent selection of clothes and a secret lipstick. Clothes that had fortunately turned out to be mostly far too tight for her wide-hipped and ample-bosomed mother, despite the middle-aged woman trying her best to squeeze into them one by one.

‘Hello. What’s this Ruby Red silliness?’ she asked.

‘That’s what I’ve decided to call you, Ruby Red. Red for short. You look like a Red. Anyway, you look nice. Where are you off to?’

With a grin Ruby held up the shopping baskets. ‘Just running shopping errands for Mum and Nan, off to queue, queue, queue in the High Street. Again. My life is one long queue, hand over coupons, queue again.’

‘See? I was right. Didn’t take them long to get you back in harness. Big brother Ray said he was going to train you back into your place, as the family slave.’

Ruby laughed. ‘Shut up! He never said it like that! Do you think I’m daft enough to let you annoy me? Ray told me all about you and what you’re like, so don’t bother.’

‘Oh, so you were interested enough to ask him about me, then? I’m flattered.’

Ruby smiled up at him shyly as he fell in step beside her, his long legs taking just one step to two of hers.

‘Not really! Anyway, I don’t really mind getting the shopping for the moment. Ma has plenty to do with her job and everything. I do it for her, not the boys. And it’s just until I can get a job and earn some money; just until I can start nursing training and live in at a hospital.’

‘But they get the benefit of everything you do – don’t you care?’

‘I already told you I don’t care.’ Ruby lied easily, not wanting Johnnie Riordan to see her as downtrodden. ‘In a way I feel sorry for Ray. He’s just jealous he didn’t get to live where I did during the war. His face nearly hit the floor when he saw it all when he came to order me home. It was so nice there – clean with lots of fresh air – it makes this bombed-out place look like a slum.’

‘Oi! Hang on now, missy.’ Johnnie stopped walking and faced her. ‘I live round here, so does my sister and her kids, and it’s all right, thank you very much. Apart from your bloody brothers, that is. If anything’s wrong round here it’s Ray and Bobbie. They lower the tone.’

Although he was half-smiling there was an anger in his words that made Ruby pull herself up. She suddenly realised what a snob she sounded.

‘Sorry, I didn’t mean it like that, I really didn’t. I meant the size of the houses and the gardens and everything – it’s all so much smaller here, and overcrowded. It’s so different from where I was out in the country with open fields, fresh air and no bomb damage, I’m still getting used to it back here.’

‘Apology accepted. I didn’t really think you’d be such a duchess, despite what your brothers say.’

Johnnie resumed walking and Ruby strode alongside him.

‘Good,’ she smiled. ‘I’m not like that at all! And yes, I did ask about you. I wanted to know who you were before I spoke to you again. But I have to say that I didn’t ask Ray – as if I’d do that – I asked Mum, and she went and told Ray.’

‘And am I all right to talk to?’ he asked.

‘No you’re not. Ray went nuts and has forbidden me to even look at you, never mind have a conversation. You are the villainous enemy, a spiv who he hates, who hates him, a really nasty piece of work and far too old. And you think you own the place.’

‘Bloody hell, Ruby, far too old? I’m only nineteen! Though, thinking about it, I suppose the rest is true enough.’

Ruby kept her expression serious for a few moments before bursting into laughter.

Johnnie joined in as they quickly turned the corner, out of sight of the street, neither of them wanting to be seen with the other by their immediate neighbours, although for different reasons.

Despite the age difference they looked good together. Ruby was tall, at five foot seven, and certainly looked older that her years in the classy tailored clothes that she had brought back with her. Despite her slenderness she was shapely, with a tiny waist, neat breasts and wavy auburn hair, which was fixed back from her face with large grips and sugar water. Johnnie meanwhile was just under six foot, with broad shoulders. His fair hair was a little too long at the front, his features were even, and he had a natural loping grace that emphasised his long legs. They made an attractive couple as they walked along together, and Ruby felt comfortable with him alongside her, albeit with a large shopping basket looped over her arm between them just to be sure.

As they strolled slowly to the High Street Ruby told him a little about the Wheatons and her life with them.

Her time in evacuation had been spent in a small village so she had socialised with a far broader age range than when she had been living in Walthamstow. Her evacuation years, during which she’d had both dancing and tennis lessons, had served her very well, leaving her self-assured, graceful, and as comfortable around boys as she was with girls; but these assets now, in her original city surroundings, made her feel like a fish out of water.

Melton in Cambridgeshire, where Ruby had been sent to stay, was situated between Cambridge and Saffron Walden, and a long bumpy bus ride from either town. In typical village style, there was just one main street, but with narrow lanes and tracks running off, leading to outlying farms and cottages. The High Street was edged with an assortment of shops and houses, with Dr George Wheaton’s surgery and family home at the top of the gently winding hill and the village school at the bottom. It was a slow and easy way of life, even in wartime, and because it was a few miles from the nearest towns, everyone knew everyone else and their business.

At the school, instead of clusters of children of the same age grouped around the playground, as there had been at Ruby’s Walthamstow school, pupils of all ages, including the evacuee children, played together both in and out of school. There had been a natural wariness on both sides when the evacuees first arrived, but after the initial settling-in period, when there were natural divisions, an integration of sorts had happened. Keith and Marian Forger, the children of the local greengrocer, had very quickly become Ruby’s closest friends.

Marian was two years older than Ruby and her brother, Keith, was Ruby’s age. They lived with their parents over the shop in the village itself, and their cousins lived about a mile away in two adjoining cottages tied to an outlying farm where their respective fathers worked. Their family was close and all the cousins played and socialised together.

It was Keith who had held out the hand of friendship to the very scared ten-year-old Ruby on her first day at the village school, and she had had a huge soft spot for him ever since. He was short and wiry, with straw-coloured hair that never quite behaved, a splattering of freckles on his nose and hazel eyes. Ruby had adored him from the very first moment he’d smiled and befriended her, and, despite rapidly outgrowing him in size and maturity, she’d continued to adore him the whole time she was there.

Keith was a rough-and-tumble boy with no academic aspirations, who was happiest helping his father in the shop and with deliveries, while his sister, Marian, was the brains of the family. She was determined to go to university and become a doctor; she was also a brilliant comedienne and imparter of the facts of life as she knew them. The five farm cousins were all experts in animal husbandry so there was nothing Ruby didn’t quickly learn about the birds and the bees and the ways of boys. The related group of children had drawn her in and become like brothers and sisters, and it had been nearly as hard to say goodbye to them as it had been to leave the Wheatons. But she’d promised she would keep in touch and had insisted she would be back as soon as possible.

As she gave Johnnie the description of her life in Melton, Ruby felt her eyes misting and a huge wave of homesickness swept over her.

‘… And I’m going to go back just as I promised, as soon as I can persuade Mum and Ray that they don’t really want me here after all. I mean, they don’t want me, they just hate the idea of me being with the Wheatons and liking it.’

‘Best of luck to you then,’ Johnnie said sympathetically. ‘I hope you manage to talk them round and then I can come and visit you. I’ve been to the seaside at Southend and up west to the city but I’ve never really been to the country apart from getting up to no good in Epping Forest a few times.’

‘Oh, it’s so different to here, all open spaces and everyone knows everyone. It’s just nicer, I suppose. We all had so much freedom. It was just so different and—’

‘OK, OK, that’s enough, I’ll take your word for it.’ Johnnie Riordan grinned as he interrupted her and held his hands up as if in defeat. He and Ruby had got to the queue outside the grocers. ‘I’ve got to see someone, so you go and get started with your shopping and I’ll meet you on the corner by the butcher’s in about an hour and help you with the rest of it. I’d take you for a tea and a bun but we might be seen.’

Ruby smiled to herself as he walked away. There was something about him that cheered her up and made her feel like a grown up. An hour later she stood on the corner and tried not to look too pleased when he came strutting along the pavement towards her.

Doing the shopping with Johnnie alongside relieved some of the monotony of standing in the various queues to get everything on her mother’s list. It was a relaxing and light-hearted few hours away from the house, but as she neared home she knew there was going to be trouble the moment she saw Ray waiting on the pavement outside. He was leaning against the gate jamb, his arms crossed and his face screwed up in anger. Ruby was relieved that she and Johnnie had parted company way before they reached their street.

Ray had one of those faces that would have been handsome if his nature had been different, but he exuded a thin-lipped violence that twisted his features and made him look unattractive and nasty.

As she looked at him she was suddenly scared, but there was no way she was going to let him see.

‘Where the fuck have you been?’ he snarled as he unfolded his arms. ‘Mum said you’ve been gone hours.’

‘Getting the shopping like Mum asked me, but what’s it got to do with you? And anyway, shouldn’t you be at work?’ Ruby asked with a smile and a lot more bravado in her voice than she felt in her heart.

‘It’s got plenty to do with me. What have you been up to all this time?’

‘Mind your own. You can’t tell me what to do or when to do it.’

He moved closer to her. ‘I’m the man of this house, head of the household, and you answer to me. Those retarded bumpkins out in the middle of nowhere might have let you roam the streets doing what you want but I won’t. Your job is to help Ma and Nan. If you have to get shopping you go and then come straight back.’

Ruby gasped as she took in his words. ‘Man of the house? Oh, do shut up. Do you know how daft you sound? This isn’t the cinema, it’s real life. You’re my brother, that’s all you are – just a brother. An equal, not a bloody overseer.’

Ruby laughed in astonishment as she went to push past him. She couldn’t believe that her brother would speak to her like that.

‘You’re a kid, you’re underage and you do as I say or else.’ He moved in front of her, blocking her way with his body.

‘Or else what? No, I do what I like and it’s none of your business. I’m not your daughter or your wife. Now get out of my way if you want supper tonight, else I’ll tip this lot out in the street and you’ll have bugger all.’

For a moment Ray looked quite shocked. He hadn’t expected her to challenge him.

‘You dare talk to me like that, you little cow! Now get into your room and stay there until I say you can come out!’

Ruby stared hard at Ray and slowly shook her head. ‘Not bloody likely. Get away from me …’

His hand flicked out and he grabbed her forcefully by the arm, dragged her down the path to the front door, then pulled her round until they were nose to nose.

‘Get indoors and get into your room or I’ll get Dad’s belt to you.’

‘You just try it, you lay one finger on me and I’ll be out of that door for good. Don’t forget, I’ve got somewhere to go.’

As soon as the words were out she regretted them. In the heat of the moment she had given Ray an insight into her thoughts.

‘That’s what you think,’ he snarled. ‘You ain’t going nowhere, never in a million years. Nowhere!’ His face was so close to hers she could feel the spittle on her cheek as he spat the words at her.

She tried to pull away from him but he just tightened his grip around the top of her arm and walked her over the doorstep into the hall before pulling his other hand back and slapping her across the face. As she reeled away he snatched the shopping basket from her before shoving her so forcefully into her bedroom she tumbled straight onto her bed. Then, before she could stand up, he took the key from the inside, slammed the door shut and locked it.

‘Now you can stay there until I say you can come out.’

She rattled the handle with one hand and massaged her face with the other. She could feel her cheek swelling and her eye starting to close.

‘Open this door,’ she screamed as loud as she could. ‘Open the door!’

But there was just silence from the other side.

Four

‘Oh, Ruby, you silly girl, what have you done to upset Ray? He’s got a fearsome temper, that lad. He’s not one to be crossed.’

Ruby looked round and realised for the first time that her grandmother was also in the room and sitting quietly in her chair by the window.

‘I haven’t done anything. He’s just being a pig because he is a pig. I hate him,’ Ruby said, fighting hard not to cry. Not because she was upset or even because she was hurt, but because she was so angry and frustrated. How dare he do that to her? Hitting her was bad enough, but locking her in her bedroom like a child? She rattled the handle loudly and kicked out at the door, hoping that her mother would come and let her out.

‘Let me out of here,’ she screamed as loudly as she could. ‘Mum? Arthur? Are you there? Someone unlock this bloody door. Ray locked me in and Nan’s inside. Mum?’

‘They won’t open the door, Ruby, not if Ray’s locked it. They’ll never cross Ray, none of them. They’re all scared of him, even your mother; and anyway, he’ll have the key in his pocket, like as not. No one’ll dare ask for it.’ Her grandmother’s tone was wearily matter-of-fact.

‘But why’s Mum scared of him? He’s her son, he should respect her, shouldn’t he?’ Ruby asked.

‘Because that Ray’s just like his father – your father – and she knows it. He doesn’t respect anyone. He’s nothing but a bullyboy and your grandfather would turn in his grave if he could see the way that boy carries on. My Ernie never liked your father right from the first day your mother brought him home, and he wouldn’t like Ray, I know that for a fact. Truly like father like son. Peas in a pod, those two.’ Pulling her shawl tighter round her shoulders she shook her head sadly. ‘The others aren’t really bad boys. Bobbie looks up to Ray, God help him, so he does as he’s told, and poor Arthur doesn’t really understand it all. But that Ray, he’s bad through and through and no one can do anything about it.’ She sighed, her whole chest heaving as if it was an effort. ‘But it’s your mother I feel for. My poor Sarah. A thug for a husband and now a thug for a son. Your mother is my only living child, even though we had three, so it hurts all the more to see her treated like that by one of her own children.’

Ruby sat on the edge of her bed and studied her grandmother, whom she knew could probably see only her outline across the room. For the first time since her return to London she was seeing her as a person; as Elsie Saunders, wife and mother, not just Nan who now lived with them all and with whom she grudgingly shared a bedroom.

Ruby had been so busy feeling sorry for herself that she hadn’t realised how hard it must be for a woman of Nan’s age to go from having her own home, where she had lived all her married life with her husband and where she had raised a family, to owning nothing and having to share a bedroom with a fifteen-year-old, eating her meals when she was told and being ordered around like a child by her own grandson.

It was too much for Ruby and she felt the tears of guilt break through and roll down her cheek. Standing up she went over the woman, leaned forward and hugged her tightly.

‘Well, I never – what was that for?’

‘Because I’m a selfish cow, Nan, and I’m sorry.’

Elsie Saunders’ eyes also filled up. ‘You’re a good girl, Ruby, and it’s a crying shame they made you come back here. Your mother shouldn’t have done that and I told her so when Ray went to get you. She should have let you get away from this, even if she can’t.’

‘I want to go back there, Nana, I want to go back so badly, and they want me back. I could finish school and get qualifications. I want to train to be a nurse. It wouldn’t mean I’d be gone for ever. Aunty Babs was teaching me how to sew my own clothes and grow fruit and vegetables, and I had real friends. But how can I go back now I know what’s going on here? I can’t leave you and Mum with Ray.’

Ruby started to cry. She didn’t want to; she didn’t want there to be any possibility of Ray finding out she was upset, but she couldn’t help it.

‘Don’t you cry, Ruby love. Listen to me: you have to go back. You can’t stop Ray being as he is, as your mother let him be, so don’t sacrifice yourself. I saw what he did – my eyes are bad, but not that bad – and anyhow, I know that sound. He’s his father’s son all right.’ She reached her hand up and gently touched her granddaughter’s swelling face. ‘Now, as we’re locked in together, why don’t you tell me all about your time away? We haven’t had time for more than a few words since you’ve been back and it would be so nice to hear all about it.’

It was Sarah who opened the door a couple of hours later. ‘Your dinner’s ready and the boys have gone out. I told Ray he shouldn’t have locked you in. He gave me the key.’

‘Then why didn’t you let us out? He locked Nan in here as well, and he hit me you know; hit me around the face. Look.’ Ruby pointed to her swollen cheek.

Her mother glanced at her. ‘That’s going to really bruise up. I’ll find the witch hazel. But you shouldn’t have upset him. He told me what you said. You wouldn’t have spoken to your father like that, would you?’ The woman pursed her lips and shook her head slowly. ‘Anyway, what’s done is done. Just remember next time, Ray can get carried away but he doesn’t mean it badly; he’s just trying to look after everyone the best he can.’

‘He is not my father. He locked the door with Nana in here. You should have let us out straight away.’ Ruby was incensed and so was her tone but her mother simply shrugged.

‘But there’s no harm done, is there? And you’ll know for next time. He is the man of the house now.’

‘Oh, stop using that expression. There’s nothing manly about him. He’s just a thug and a bully. I hate him.’

Her mother didn’t answer straight away; she simply frowned and looked from her daughter to her mother in bemusement, as if she really didn’t understand what Ruby was so upset about.

‘I don’t think you understand, Ruby. Your brothers, especially Ray, work hard to keep this family going now your father’s gone. Without them I’d probably end up in the workhouse. It’s not asking much of you to help me look after them and your nan. Don’t forget while you were living the life of Riley with the la-di-dah Wheatons, the boys were here working, I was working, and we were all trying to survive the Blitz.’

‘But you sent me away. I didn’t ask to go,’ Ruby shouted.

‘Yes we did. We sent you for your own safety, but you were meant to come back!’

Ruby stared at her mother. Sarah Blakeley was an attractive woman who had kept her looks despite everything she’d been through. There were lines across her forehead and around her eyes, and her lips were pinched, but she still retained her shapely figure and feminine legs that suited high heels. However, she rarely smiled spontaneously, her eyes were constantly unhappy and when she spoke her voice was a monotone. She wasn’t enjoying her life, she was just going through the motions.

After her long chat with her grandmother when they were locked in the bedroom, Ruby had promised that she would try to be understanding of her mother, and at that moment she could see why the woman gave in to Ray on everything. It was the route to an easier life with fewer arguments. Arguments she knew she couldn’t win. She had been bullied and ground down by her own husband all her married life so it had become part of her nature to accept it as her lot in life. Ray had simply stepped straight into his father’s vacant shoes and she had let him. The treadmill for Sarah Blakeley just carried on with no end in sight and although Ruby felt for her she had no intention of getting on it herself.

In bed that night, with Elsie on the other side of the room snoring and snuffling and keeping her awake, Ruby pulled her eiderdown up to her chin and thought about her afternoon with Johnnie from down the street. Those had been the most carefree hours she’d had since her return. He’d made her laugh as she stood in the queues, bought her an icecream and then helped her carry the shopping. He was blatantly experienced in the ways of the world, maybe overly confident, and from what she’d heard was certainly involved in a great many dodgy dealings, but that added an element of danger that attracted her.

On the other side of the coin he spoke lovingly of his family and had a kindly streak that had been obvious the first time she’d met him. As she thought about Johnnie Riordan she couldn’t help but focus on the resentment that existed between him and Ray and wonder if there was some way she could use her newfound friendship with Johnnie to get her own back on her brother.

It was easy for her mother to shrug off Ray’s behaviour, but she couldn’t. Ray had hit her and treated her as a child – her own brother had acted as if she was his child instead of a sibling – and she had no intention of letting that go without taking some sort of revenge that would punish him and, at the same time, distract him enough to allow her to make her escape back to Melton.

She knew that although Johnnie Riordan worked legitimately in a public house he was also a wheeler-dealer with a finger in many pies, some legal, some not. He bought and sold anything that might earn him a few bob, including the things that the ordinary man in the street had no access to in times of rationing and shortages. It had taken her a while to figure out why Ray hated Johnnie so much. Now she knew: it was because he was jealous; because he really wanted to be a part of those activities himself but he didn’t have a quick enough brain to think things up for himself.

Ruby wondered if she could find a way to make that work in her favour, and as she finally dozed off a plan was coming together in her head.

‘You know what, Roger, I’m gonna have to sort this out right now. I’ve got no choice. I can’t let those pricks get away with it any longer, not now they’re messing around close to home – to my home. If I roll over and let them carry on taking the mick like this then every upstart in Walthamstow and beyond will be trying to get his foot in the door – my door, on my turf.’

His irritation bubbling away, Johnnie Riordan slammed his fist down hard on the table, making the teacups rattle in their saucers and his brother-in-law jump nervously.

‘But how’s it your turf?’ the other man frowned. ‘You don’t own Walthamstow, and anyway, what do you reckon you can do to stop them?’

‘That’s what I’ve got to decide. Any ideas?’ Johnnie asked out of kindness more than anything. He didn’t really expect a workable answer.

‘I’m new at this lark so I don’t know nothing; I’m not like you. It’s hard for me after what’s happened and I just don’t bloody well understand any of it. I can’t do it.’