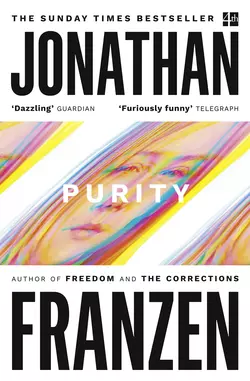

Purity

Jonathan Franzen

The Sunday Times bestseller from the author of Freedom and The CorrectionsYoung Pip Tyler doesn’t know who she is. She knows that her real name is Purity, that she’s saddled with $130,000 in student debt, that she’s squatting with anarchists in Oakland, and that her relationship with her mother – her only family – is hazardous. But she doesn’t have a clue who her father is, why her mother chose to live as a recluse with an invented name, or how she’ll ever have a normal life.Enter the Germans. A glancing encounter with a German peace activist leads Pip to an internship in South America with the Sunlight Project, an organization that traffics in all the secrets of the world – including, Pip hopes, the secret of her origins. TSP is the brainchild of Andreas Wolf, a charismatic provocateur who rose to fame in the chaos following the fall of the Berlin Wall. Now on the lam in Bolivia, Andreas is drawn to Pip for reasons she doesn’t understand, and the intensity of her response to him upends her conventional ideas of right and wrong.Jonathan Franzen’s Purity is a grand story of youthful idealism, extreme fidelity, and murder. The author of The Corrections and Freedom has imagined a world of vividly original characters – Californians and East Germans, good parents and bad parents, journalists and leakers – and he follows their intertwining paths through landscapes as contemporary as the omnipresent Internet and as ancient as the war between the sexes. Purity is the most daring and penetrating book yet by one of the major writers of our time.

Copyright (#ulink_00b7fd6e-0e8a-5890-b65c-d695ffcf56b4)

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thestate.co.uk (http://www.4thestate.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate in 2015

First published in the United States by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in 2015

Copyright © Jonathan Franzen 2015

Cover image © Image Source/Getty Images

Jonathan Franzen asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This is a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it either are the work of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007532766

Ebook Edition © September 2015 ISBN: 9780007532797

Version: 2017-03-28

Dedication (#ulink_531fdd7c-76f7-5dec-b82b-f78d06fa69b0)

for Elisabeth Robinson

… Die stets das Böse will und stets das Gute schafft

Contents

Cover (#u0353ffd1-3b4f-53f8-ae37-758a58db93a3)

Title Page (#u7dc03347-8f8d-503d-9a02-48287751fed2)

Copyright (#u83669e31-ac76-5c30-b4a6-5f014ded5530)

Dedication (#ue1f67975-0731-5ff8-951d-9fdf62fcb0c0)

Purity in Oakland (#u1f70ed36-1767-599a-9975-f8e270c1d86c)

The Republic of Bad Taste (#uac10956a-7fbd-52b9-b657-55070029d51d)

Too Much Information (#litres_trial_promo)

Moonglow Dairy (#litres_trial_promo)

[le1o9n8a0rd] (#litres_trial_promo)

The Killer (#litres_trial_promo)

The Rain Comes (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Jonathan Franzen (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Purity in Oakland (#ulink_cdf04fc9-e573-5a46-9e77-493679f03b1e)

MONDAY

Oh pussycat, I’m so glad to hear your voice,” the girl’s mother said on the telephone. “My body is betraying me again. Sometimes I think my life is nothing but one long process of bodily betrayal.”

“Isn’t that everybody’s life?” the girl, Pip, said. She’d taken to calling her mother midway through her lunch break at Renewable Solutions. It brought her some relief from the feeling that she wasn’t suited for her job, that she had a job that nobody could be suited for, or that she was a person unsuited for any kind of job; and then, after twenty minutes, she could honestly say that she needed to get back to work.

“My left eyelid is drooping,” her mother explained. “It’s like there’s a weight on it that’s pulling it down, like a tiny fisherman’s sinker or something.”

“Right now?”

“Off and on. I’m wondering if it might be Bell’s palsy.”

“Whatever Bell’s palsy is, I’m sure you don’t have it.”

“If you don’t even know what it is, pussycat, how can you be so sure?”

“I don’t know—because you didn’t have Graves’ disease? Hyper-thyroidism? Melanoma?”

It wasn’t as if Pip felt good about making fun of her mother. But their dealings were all tainted by moral hazard, a useful phrase she’d learned in college economics. She was like a bank too big in her mother’s economy to fail, an employee too indispensable to be fired for bad attitude. Some of her friends in Oakland also had problematic parents, but they still managed to speak to them daily without undue weirdnesses transpiring, because even the most problematic of them had resources that consisted of more than just their single offspring. Pip was it, as far as her own mother was concerned.

“Well, I don’t think I can go to work today,” her mother said. “My Endeavor is the only thing that makes that job survivable, and I can’t connect with the Endeavor when there’s an invisible fisherman’s sinker pulling on my eyelid.”

“Mom, you can’t call in sick again. It’s not even July. What if you get the actual flu or something?”

“And meanwhile everybody’s wondering what this old woman with half her face drooping onto her shoulder is doing bagging their groceries. You have no idea how I envy you your cubicle. The invisibility of it.”

“Let’s not romanticize the cubicle,” Pip said.

“This is the terrible thing about bodies. They’re so visible, so visible.”

Pip’s mother, though chronically depressed, wasn’t crazy. She’d managed to hold on to her checkout-clerk job at the New Leaf Community Market in Felton for more than ten years, and as soon as Pip relinquished her own way of thinking and submitted to her mother’s she could track what she was saying perfectly well. The only decoration on the gray segments of her cubicle was a bumper sticker, AT LEAST THE WAR ON THE ENVIRONMENT IS GOING WELL. Her colleagues’ cubicles were covered with photos and clippings, but Pip herself understood the attraction of invisibility. Also, she expected to be fired any month now, so why settle in.

“Have you given any thought to how you want to not-celebrate your not-birthday?” she asked her mother.

“Frankly, I’d like to stay in bed all day with the covers over my head. I don’t need a not-birthday to remind me I’m getting older. My eyelid is doing a very good job of that already.”

“Why don’t I make you a cake and I’ll come down and we can eat it. You sound sort of more depressed than usual.”

“I’m not depressed when I see you.”

“Ha, too bad I’m not available in pill form. Could you handle a cake made with stevia?”

“I don’t know. Stevia does something funny to the chemistry of my mouth. There’s no fooling a taste bud, in my experience.”

“Sugar has an aftertaste, too,” Pip said, although she knew that argument was futile.

“Sugar has a sour aftertaste that the taste bud has no problem with, because it’s built to report sourness without dwelling on it. The taste bud doesn’t have to spend five hours registering strangeness, strangeness! Which was what happened to me the one time I drank a stevia drink.”

“But I’m saying the sourness does linger.”

“There’s something very wrong when a taste bud is still reporting strangeness five hours after you had a sweetened drink. Do you know that if you smoke crystal meth even once, your entire brain chemistry is altered for the rest of your life? That’s what stevia tastes like to me.”

“I’m not sitting here puffing on a meth stem, if that’s what you’re trying to say.”

“I’m saying I don’t need a cake.”

“No, I’ll find a different kind of cake. I’m sorry I suggested a kind that’s poison to you.”

“I didn’t say it was poison. It’s simply that stevia does something funny—”

“To your mouth chemistry, yeah.”

“Pussycat, I’ll eat whatever kind of cake you bring me, refined sugar won’t kill me, I didn’t mean to upset you. Sweetheart, please.”

No phone call was complete before each had made the other wretched. The problem, as Pip saw it—the essence of the handicap she lived with; the presumable cause of her inability to be effective at anything—was that she loved her mother. Pitied her; suffered with her; warmed to the sound of her voice; felt an unsettling kind of nonsexual attraction to her body; was solicitous even of her mouth chemistry; wished her greater happiness; hated upsetting her; found her dear. This was the massive block of granite at the center of her life, the source of all the anger and sarcasm that she directed not only at her mother but, more and more self-defeatingly of late, at less appropriate objects. When Pip got angry, it wasn’t really at her mother but at the granite block.

She’d been eight or nine when it occurred to her to ask why her birthday was the only one celebrated in their little cabin, in the redwoods outside Felton. Her mother had replied that she didn’t have a birthday; the only one that mattered to her was Pip’s. But Pip had pestered her until she agreed to celebrate the summer solstice with a cake that they would call not-birthday. This had then raised the question of her mother’s age, which she’d refused to divulge, saying only, with a smile suitable to the posing of a koan, “I’m old enough to be your mother.”

“No, but how old are you really?”

“Look at my hands,” her mother had said. “If you practice, you can learn to tell a woman’s age by her hands.”

And so—for the first time, it seemed—Pip had looked at her mother’s hands. The skin on the back of them wasn’t pink and opaque like her own skin. It was as if the bones and veins were working their way to the surface; as if the skin were water receding to expose shapes at the bottom of a harbor. Although her hair was thick and very long, there were dry-looking strands of gray in it, and the skin at the base of her throat was like a peach a day past ripe. That night, Pip lay awake in bed and worried that her mother might die soon. It was her first premonition of the granite block.

She’d since come fervently to wish that her mother had a man in her life, or really just one other person of any description, to love her. Potential candidates over the years had included their next-door neighbor Linda, who was likewise a single mom and likewise a student of Sanskrit, and the New Leaf butcher, Ernie, who was likewise a vegan, and the pediatrician Vanessa Tong, whose powerful crush on Pip’s mother had taken the form of trying to interest her in birdwatching, and the mountain-bearded handyman Sonny, for whom no maintenance job was too small to occasion a discourse on ancient Pueblo ways of being. All these good-hearted San Lorenzo Valley types had glimpsed in Pip’s mother what Pip herself, in her early teens, had seen and felt proud of: an ineffable sort of greatness. You didn’t have to write to be a poet, you didn’t have to create things to be an artist. Her mother’s spiritual Endeavor was itself a kind of art—an art of invisibility. There was never a television in their cabin and no computer before Pip turned twelve; her mother’s main source of news was the Santa Cruz Sentinel, which she read for the small daily pleasure of being appalled by the world. In itself, this was not so uncommon in the Valley. The trouble was that Pip’s mother herself exuded a shy belief in her greatness, or at least carried herself as if she’d once been great, back in a pre-Pip past that she categorically refused to talk about. She wasn’t so much offended as mortified that their neighbor Linda could compare her frog-catching, mouth-breathing son, Damian, to her own singular and perfect Pip. She imagined that the butcher would be permanently shattered if she told him that he smelled to her like meat, even after a shower; she made herself miserable dodging Vanessa Tong’s invitations rather than just admit she was afraid of birds; and whenever Sonny’s high-clearance pickup rolled into their driveway she made Pip go to the door while she fled out the back way and into the redwoods. What gave her the luxury of being impossibly choosy was Pip. Over and over, she’d made it clear: Pip was the only person who passed muster, the only person she loved.

This all became a source of searing embarrassment, of course, when Pip hit adolescence. And by then she was too busy hating and punishing her mother to clock the damage that her mother’s unworldliness was doing to her own life prospects. Nobody was there to tell her that it might not be the best idea, if she wanted to set about doing good in the world, to graduate from college with $130,000 in student debt. Nobody had warned her that the figure to pay attention to when she was being interviewed by Igor, the head of consumer outreach at Renewable Solutions, was not the “thirty or forty thousand dollars” in commissions that he foresaw her earning in her very first year but the $21,000 base salary he was offering, or that a salesman as persuasive as Igor might also be skilled at selling shit jobs to unsuspecting twenty-one-year-olds.

“About the weekend,” Pip said in a hard voice. “I have to warn you that I want to talk about something you don’t like to talk about.”

Her mother gave a little laugh intended to be winsome, to signal defenselessness. “There’s only one thing I don’t like to talk about with you.”

“Well, and that is exactly the thing I want to talk about. So just be warned.”

Her mother said nothing to this. Down in Felton, the fog would have burned off by now, the fog that her mother was daily sorry to see go, because it revealed a bright world to which she preferred not to belong. She practiced her Endeavor best in the safety of gray morning. Now there would be sunlight, greened and goldened by filtration through the redwoods’ tiny needles, summer heat stealing through the sleeping porch’s screened windows and over the bed that Pip had claimed as a privacy-craving teenager, relegating her mother to a cot in the main room until she left for college and her mother took it back. She was probably on the bed practicing her Endeavor right now. If so, she wouldn’t speak again until spoken to; she would be all breathing.

“This isn’t personal,” Pip said. “I’m not going anywhere. But I need money, and you don’t have any, and I don’t have any, and there’s only one place I can think to get it. There’s only one person who even theoretically owes me. So we’re going to talk about it.”

“Pussycat,” her mother said sadly, “you know I won’t do that. I’m sorry you need money, but this isn’t a matter of what I like or don’t like. It’s a matter of can or can’t. And I can’t, so we’ll have to think of something else for you.”

Pip frowned. Every so often, she felt the need to strain against the circumstantial straitjacket in which she’d found herself two years earlier, to see if there might be a little new give in its sleeves. And, every time, she found it exactly as tight as before. Still $130,000 in debt, still her mother’s sole comfort. It was kind of remarkable how instantly and totally she’d been trapped the minute her four years of college freedom ended; it would have depressed her, had she been able to afford being depressed.

“OK, I’m going to hang up now,” she said into the phone. “You get yourself ready for work. Your eye’s probably just bothering you because you’re not sleeping enough. It happens to me sometimes when I don’t sleep.”

“Really?” her mother said eagerly. “You get this, too?”

Although Pip knew that it would prolong the call, and possibly entail extending the discussion to genetically heritable diseases, and certainly require copious fibbing on her part, she decided that her mother was better off thinking about insomnia than about Bell’s palsy, if only because, as Pip had been pointing out to her for years, to no avail, there were actual medications she could take for her insomnia. But the result was that when Igor stuck his head in Pip’s cubicle, at 1:22, she was still on the phone.

“Mom, sorry, gotta go right now, good-bye,” she said, and hung up.

Igor was Gazing at her. He was a blond Russian, strokably bearded, unfairly handsome, and to Pip the only conceivable reason he hadn’t fired her was that he enjoyed thinking about fucking her, and yet she was sure that, if it ever came to that, she would end up humiliated in no time flat, because he was not only handsome but rather handsomely paid, while she was a girl with nothing but problems. She was sure that he must know this, too.

“I’m sorry,” she said to him. “I’m sorry I went seven minutes over. My mom had a medical issue.” She thought about this. “Actually, cancel that, I’m not sorry. What are the chances of me getting a positive response in any given seven-minute period?”

“Did I look censorious?” Igor said, batting his eyelashes.

“Well, why are you sticking your head in? Why are you staring at me?”

“I thought you might like to play Twenty Questions.”

“I think not.”

“You try to guess what I want from you, and I’ll confine my answers to an innocuous yes or no. Let the record show: only yeses, only nos.”

“Do you want to get sued for sexual harassment?”

Igor laughed, delighted with himself. “That’s a no! Now you have nineteen questions.”

“I’m not kidding about the lawsuit. I have a law-school friend who says it’s enough that you create an atmosphere.”

“That’s not a question.”

“How can I explain to you how not funny to me this is?”

“Yes–no questions only, please.”

“Jesus Christ. Go away.”

“Would you rather talk about your May performance?”

“Go away! I’m getting on the phone right now.”

When Igor was gone, she brought up her call sheet on her computer, glanced at it with distaste, and minimized it again. In four of the twenty-two months she’d worked for Renewable Solutions, she’d succeeded in being only next-to-last, not last, on the whiteboard where her and her associates’ “outreach points” were tallied. Perhaps not coincidentally, four out of twenty-two was roughly the frequency with which she looked in a mirror and saw someone pretty, rather than someone who, if it had been anybody but her, might have been considered pretty but, because it was her, wasn’t. She’d definitely inherited some of her mother’s body issues, but she at least had the hard evidence of her experience with boys to back her up. Many were quite attracted to her, few ended up not thinking there’d been some error. Igor had been trying to puzzle it out for two years now. He was forever studying her the way she studied herself in the mirror: “She seemed good-looking yesterday, and yet …”

From somewhere, in college, Pip had gotten the idea—her mind was like a balloon with static cling, attracting random ideas as they floated by—that the height of civilization was to spend Sunday morning reading an actual paper copy of the Sunday New York Times at a café. This had become her weekly ritual, and, in truth, wherever the idea had come from, her Sunday mornings were when she felt most civilized. No matter how late she’d been out drinking, she bought the Times at 8 a.m., took it to Peet’s Coffee, ordered a scone and a double cappuccino, claimed her favorite table in the corner, and happily forgot herself for a few hours.

The previous winter, at Peet’s, she’d become aware of a nice-looking, skinny boy who had the same Sunday ritual. Within a few weeks, instead of reading the news, she was thinking about how she looked to the boy while reading, and whether to raise her eyes and catch him looking, until finally it was clear that she would either have to find a new café or talk to him. The next time she caught his eye, she attempted an invitational head-tilt that felt so creaky and studied that she was shocked by how instantly it worked. The boy came right over and boldly proposed that, since they were both there at the same time every week, they could start sharing a paper and save a tree.

“What if we both want the same section?” Pip said with some hostility.

“You were here before I was,” the boy said, “so you could have first choice.” He went on to complain that his parents, in College Station, Texas, had the wasteful practice of buying two copies of the Sunday Times, to avoid squabbling over sections.

Pip, like a dog that knows only its name and five simple words in human language, heard only that the boy came from a normal twoparent family with money to burn. “But this is kind of my one time entirely for myself all week,” she said.

“I’m sorry,” the boy said, backing away. “It just looked like you wanted to say something.”

Pip didn’t know how not to be hostile to boys her own age who were interested in her. Part of it was that the only person in the world she trusted was her mother. From her experiences in high school and college, she’d already learned that the nicer the boy was, the more painful it would be for both of them when he discovered that she was much more of a mess than her own niceness had led him to believe. What she hadn’t yet learned was how not to want somebody to be nice to her. The not-nice boys were particularly adept at sensing this and exploiting it. Thus neither the nice ones nor the not-nice ones could be trusted, and she was, moreover, not very good at telling the two apart until she was in bed with them.

“Maybe we could have coffee some other time,” she said to the boy. “Some not-Sunday morning.”

“Sure,” he said uncertainly.

“Because now that we’ve actually spoken, we don’t have to keep looking at each other. We can just read our separate papers, like your parents.”

“My name’s Jason, by the way.”

“I’m Pip. And now that we know each other’s names, we especially don’t have to keep looking at each other. I can think, oh, that’s just Jason, and you can think, oh, that’s just Pip.”

He laughed. It turned out that he had a degree in math from Stanford and was living the math major’s dream, working for a foundation that promoted American numeracy while trying to write a textbook that he hoped would revolutionize the teaching of statistics. After two dates, she liked him enough to think she’d better sleep with him before he or she got hurt. If she waited too long, Jason would learn that she was a mess of debts and duties, and would run for his life. Or she would have to tell him that her deeper affections were engaged with an older guy who not only didn’t believe in money—as in U.S. currency; as in the mere possession of it—but also had a wife.

So as not to be totally undisclosive, she told Jason about the afterhours volunteer “work” that she was doing on nuclear disarmament, a subject he seemed to know so much more about than she did, despite its being her “work,” not his, that she became slightly hostile. Fortunately, he was a great talker, an enthusiast for Philip K. Dick, for Breaking Bad, for sea otters and mountain lions, for mathematics applied to daily life, and especially for his geometrical method of statistics pedagogy, which he explained so well she almost understood it. The third time she saw him, at a noodle joint where she was forced to pretend not to be hungry because her latest Renewable Solutions paycheck hadn’t cleared yet, she found herself at a crossroads: either risk friendship or retreat to the safety of casual sex.

Outside the restaurant, in light fog, in the Sunday-evening quiet of Telegraph Avenue, she put the moves on Jason and he responded avidly. She could feel her stomach growling as she pressed it into his; she hoped he couldn’t hear it.

“Do you want to go to your house?” she murmured in his ear.

Jason said no, regrettably, he had a sister visiting.

At the word sister, Pip’s heart constricted with hostility. Having no siblings of her own, she couldn’t help resenting the demands and potential supportiveness of other people’s; their nuclear-family normalcy, their inherited wealth of closeness.

“We can go to my house,” she said, somewhat crossly. And she was so absorbed in resenting Jason’s sister for displacing her from his bedroom (and, by extension, from his heart, although she didn’t particularly want a place in it), so vexed by her circumstances as she and Jason walked hand in hand down Telegraph Avenue, that they’d reached the door of her house before she remembered that they couldn’t go there.

“Oh,” she said. “Oh. Could you wait outside for a second while I deal with something?”

“Um, sure,” Jason said.

She gave him a grateful kiss, and they proceeded to neck and grind for ten minutes on her doorstep, Pip burying herself in the pleasure of being touched by a clean and highly competent boy, until a distinctly audible growl from her stomach brought her out of it.

“One second, OK?” she said.

“Are you hungry?”

“No! Or actually suddenly maybe yes, slightly. I wasn’t at the restaurant, though.”

She eased her key into the lock and went inside. In the living room, her schizophrenic housemate, Dreyfuss, was watching a basketball game with her disabled housemate, Ramón, on a scavenged TV set whose digital converter a third housemate, Stephen, the one she was more or less in love with, had obtained by sidewalk barter. Dreyfuss’s body, bloated by the medications that he’d to date been good about taking, filled a low, scavenged armchair.

“Pip, Pip,” Ramón cried out, “Pip, what are you doing now, you said you might help me with my vocabbleree, you wanna help me with it now?”

Pip put a finger to her lips, and Ramón clapped his hands over his mouth.

“That’s right,” said Dreyfuss quietly. “She doesn’t want anyone to know she’s here. And why might that be? Could it be because the German spies are in the kitchen? I use the word spies loosely, of course, though perhaps not entirely inappropriately, given the fact that there are some thirty-five members of the Oakland Nuclear Disarmament Study Group, of which Pip and Stephen are by no means the least dispensable, and yet the house that the Germans have chosen to favor with their all too typically German earnestness and nosiness, for nearly a week now, is ours. A curious fact, worth considering.”

“Dreyfuss,” Pip hissed, moving closer to him to avoid raising her voice.

Dreyfuss placidly knit his fat fingers on his belly and continued speaking to Ramón, who never tired of listening to him. “Could it be that Pip wants to avoid talking to the German spies? Perhaps especially tonight? When she’s brought home a young gentleman with whom she’s been osculating on the front porch for some fifteen minutes now?”

“You’re the spy,” Pip whispered furiously. “I hate your spying.”

“She hates it when I observe things that no intelligent person could fail to notice,” Dreyfuss explained to Ramón. “To observe what’s in plain sight is not to spy, Ramón. And perhaps the Germans, too, are doing no more than that. What constitutes a spy, however, is motive, and there, Pip—” He turned to her. “There I would advise you to ask yourself what these nosy, earnest Germans are doing in our house.”

“You didn’t stop taking your meds, did you?” Pip whispered.

“Osculate, Ramón. There’s a fine vocabulary word for you.”

“Whassit mean?”

“Why, it means to neck. To lock lips. To pluck up kisses by their roots.”

“Pip, you gonna help me with my vocabbleree?”

“I believe she has other plans tonight, my friend.”

“Sweetie, no, not now,” Pip whispered to Ramón, and then, to Dreyfuss, “The Germans are here because we invited them, because we had room. But you’re right, I need you not to tell them I’m here.”

“What do you think, Ramón?” Dreyfuss said. “Should we help her? She’s not helping you with your vocabulary.”

“Oh, for Christ’s sake. Help him yourself. You’re the one with the huge vocabulary.”

Dreyfuss turned again to Pip and looked at her steadily, his eyes all intellect, no affect. It was as if his meds suppressed his condition well enough to keep him from butchering people in the street with a broadsword but not quite enough to banish it from his eyes. Stephen had assured Pip that Dreyfuss looked at everyone the same way, but she persisted in thinking that, if he ever stopped taking his meds, she would be the person he went after with a broadsword or whatever, the person in whom he would pinpoint the trouble in the world, the conspiracy against him; and, what’s more, she believed that he was seeing something true about her falseness.

“These Germans and their spying are distasteful to me,” Dreyfuss said to her. “Their first thought when they walk into a house is how to take it over.”

“They’re peace activists, Dreyfuss. They stopped trying to be world conquerors, like, seventy years ago.”

“I want you and Stephen to make them go away.”

“OK! We will! Later. Tomorrow.”

“We don’t like the Germans, do we, Ramón?”

“We like it when it’s jus’ the five of us, like famlee,” Ramón said.

“Well … not a family. Not exactly. No. We each have our own families, don’t we, Pip?”

Dreyfuss looked into her eyes again, significantly, knowingly, with no human warmth—or was it maybe simply no trace of desire? Maybe every man would look at her this heartlessly if sex were entirely subtracted? She went over to Ramón and put her hands on his fat, sloping shoulders. “Ramón, sweetie, I’m busy tonight,” she said. “But I’ll be home all night tomorrow. OK?”

“OK,” he said, completely trusting her.

She hurried back to the front door and let in Jason, who was blowing on his cupped fingers. As they passed by the living room, Ramón again clapped his hands to his mouth, miming his commitment to secrecy, while Dreyfuss imperturbably watched basketball. There were so many things for Jason to see in the house and so few that Pip cared for him to see, and Dreyfuss and Ramón each had a smell, Dreyfuss’s yeasty, Ramón’s uriney, that she was used to but visitors weren’t. She climbed the stairs rapidly on tiptoe, hoping that Jason would get the idea to hurry and be quiet. From behind a closed door on the second floor came the familiar cadences of Stephen and his wife finding fault with each other.

In her little bedroom, on the third floor, she led Jason to her mattress without turning any lights on, because she didn’t want him to see how poor she was. She was horribly poor but her sheets were clean; she was rich in cleanliness. When she’d moved into the room, a year earlier, she’d scrubbed every inch of floor and windowsill, using a spray bottle of disinfectant cleaner, and when mice had come to visit her she’d learned from Stephen that stuffing steel wool into every conceivable ingress point would keep them out, and then she’d cleaned the floors again. But now, after tugging Jason’s T-shirt up over his bony shoulders and letting him undress her and engaging in various pleasurable preliminaries, only to recall that her only condoms were in the toiletries bag that she’d left in the first-floor bathroom before going out, because the Germans had occupied her regular bathroom, her cleanliness became another handicap. She gave Jason’s cleanly circumcised erection a peck with her lips, murmured, “Sorry, one second, I’ll be right back,” and grabbed a robe that she didn’t get fully arranged and knotted until she was halfway down the last flight of stairs and realized she’d neglected to explain where she was going.

“Fuck,” she said, pausing on the stairs. Nothing about Jason had suggested wild promiscuity, and she possessed a still-valid morningafter prescription, and she was feeling, at that moment, as if sex were the only thing in her life that she was reasonably effective at; but she had to try to keep her body clean. Self-pity seeped into her, a conviction that for no one but her was sex so logistically ungainly, a tasty fish with so many small bones. Behind her, behind the marital bedroom door, Stephen’s wife was raising her voice on the subject of moral vanity.

“I’ll take my chances with moral vanity,” Stephen interrupted, “when the alternative is signing on with a divine plan that immiserates four billion people.”

“That is the essence of moral vanity!” the wife crowed.

Stephen’s voice triggered in Pip a longing deeper than any she felt for Jason, and she quickly concluded that she herself wasn’t guilty of moral vanity—was more like a case of moral low self-esteem, since the man she really wanted was not the one she was intent on fucking now. She tiptoed down to the ground floor and past the piles of scavenged building supplies in the hallway. In the kitchen, the German woman, Annagret, was speaking German. Pip darted into the bathroom, stuffed a three-strip of condoms into the pocket of her robe, peeked out of the door again, and pulled her head back quickly: Annagret was now standing in the kitchen doorway.

Annagret was a dark-eyed beauty and had a pleasing voice, confounding Pip’s preconceptions about the ugliness of German and the blue eyes of its speakers. She and her boyfriend, Martin, were vacationing in various American slums, ostensibly to raise awareness of their international squatters’ rights organization, and to forge connections with the American antinuke movement, but primarily, it seemed, to take pictures of each other in front of optimistic ghetto murals. The previous Tuesday evening, at a communal dinner that Pip had attended unavoidably, because it was her night to cook, Stephen’s wife had picked a fight with Annagret on the subject of Israel’s nuclear arms program. Stephen’s wife was one of those women who held another woman’s beauty against her (the fact that she held nothing against Pip, but tried to be maternal to her instead, confirmed Pip’s nongrandiose assessment of her own looks), and Annagret’s effortless loveliness, more accentuated than marred by her savage haircut and her severally pierced eyebrows, had upset Stephen’s wife so much that she began saying blatantly untrue things about Israel. Since it happened that Israel’s nuclear arms program was the one disarmament subject that Pip was well versed in, having recently prepared a report on it for the study group, and since she was also sorely jealous of Stephen’s wife, she’d cut loose with an eloquent five-minute summary of the evidence for Israeli nuclear capability.

Ridiculously, this had fascinated Annagret. Pronouncing herself “super impressed” with Pip, she led her away from the others and into the living room, where they sat on the sofa and had a long girl talk. There was something irresistible about Annagret’s attentions, and when she began to talk about the famous Internet outlaw Andreas Wolf, whom it turned out she knew personally, and to say that Pip was exactly the kind of young person that Wolf’s Sunlight Project was in need of, and to insist that Pip leave her terrible exploitative job and apply for one of the paid internships that the Sunlight Project was now offering, and to say that very probably, to win one of these internships, all she had to do was submit to a formal “questionnaire” that Annagret herself could administer before she left town, Pip had felt so flattered—so wanted—that she promised to do the questionnaire. She’d been drinking jug wine steadily for four hours.

The next morning, sober, she’d regretted her promise. Andreas Wolf and his Project were currently conducting business out of South America, owing to various European and American warrants for his arrest on hacking and spying charges, and there was obviously no way that Pip was leaving her mother and moving to South America. Also, although Wolf was a hero to some of her friends and she was moderately intrigued by Wolf’s idea that secrecy was oppression and transparency freedom, she wasn’t a politically committed person; she mostly just tagged along with Stephen, dabbling in commitment in the same fitful way she dabbled in physical fitness. Also, the Sunlight Project, and the fervor with which Annagret had spoken of it, seemed possibly cultish. Also, as she was certain would become instantly clear when she did the questionnaire, she was nowhere near as smart and well-informed as her five-minute speech on Israel had made her seem. And so she’d been avoiding the Germans until this morning, when, on her way out to share the Sunday Times with Jason, she’d found a note from Annagret whose tone was so injured that she’d left a note of her own outside Annagret’s door, promising to talk to her tonight.

Now, as her stomach continued to register emptiness, she waited for some change in the stream of spoken German to indicate that Annagret was no longer in the kitchen doorway. Twice, like a dog overhearing human speech, Pip was pretty sure that she heard her own name in the stream. If she’d been thinking straight, she would have marched into the kitchen, announced that she had a boy over and couldn’t do the questionnaire, and gone upstairs. But she was starving, and sex was becoming more of an abstract task.

Finally she heard footsteps, the scrape of a kitchen chair. She bolted from the bathroom but snagged the hem of her robe on something. A nail in a piece of scavenged wood. As she danced out of the way of falling lumber, Annagret’s voice came up the hall behind her.

“Pip? Pip, I’m looking for you since three days ago!”

Pip turned around to see Annagret advancing.

“Hi, yeah, sorry,” she said, hastily restacking the lumber. “I can’t right now. I’ve got … How about tomorrow?”

“No,” Annagret said, smiling, “come now. Come, come, like you promised.”

“Um.” Pip’s mind was not prioritizing well. The kitchen, where the Germans were, was also where cornflakes and milk were. Maybe it wouldn’t be so terrible if she ate something before returning to Jason? Might she not be more effective, more responsive and energetic, if she could have some cornflakes first? “Let me just run upstairs for one second,” she said. “One second, OK? I promise I’ll be right back.”

“No, come, come. Come now. It takes only a few minutes, ten minutes. You’ll see, it’s fun, it’s only a form we have to follow. Come. We’re waiting the whole evening for you. You’ll come do it now, ja?”

Beautiful Annagret beckoned to her. Pip could see what Dreyfuss meant about the Germans; and yet there was relief in taking orders from someone. Plus, she’d already been downstairs for so long that it would be unpleasant to go up and beg Jason for further patience, and her life was already so fraught with unpleasantnesses that she’d adopted the strategy of delaying encounters with them as long as possible, even when the delay made it likely that they would be even more unpleasant when she did encounter them.

“Dear Pip,” Annagret said, stroking Pip’s hair when she was seated at the kitchen table and eating a large bowl of cornflakes and not greatly in the mood to have her hair touched. “Thank you for doing this for me.”

“Let’s just get through it quickly, OK?”

“Yes, you’ll see. It’s only a form we have to follow. You remind me so much of myself when I was at your age and needed a purpose in my life.”

Pip didn’t care for the sound of this. “OK,” she said. “I’m sorry to ask, but is the Sunlight Project a cult?”

“Cult?” Martin, all stubble and Palestinian kaffiyeh, laughed from the end of the table. “Cult of personality, maybe.”

“Ist doch Quatsch, du,” Annagret said with some heat. “Also wirklich.”

“Sorry, what?” Pip said.

“I said it’s really bullshit, what he’s saying. The Project is the opposite of cult. It’s about honesty, truth, transparency, freedom. The governments with a cult of personality are the ones who hate it.”

“But the Project has a very cherissmetic leader,” Martin said.

“Charismatic?” Pip said.

“Charismatic. I made it sound like arissmetic. Andreas Wolf is very charismatic.” Martin laughed again. “This could nearly be in a textbook for vocabulary. How to use the word charismatic in a sentence. ‘Andreas Wolf is very charismatic.’ Then the sentence makes immediate sense, you know right away what the word means. He is the definition of the word itself.”

Martin seemed to be needling Annagret and Annagret not liking it; and Pip saw, or thought she saw, that Annagret had slept with Andreas Wolf at some point in the past. She was at least ten years older than Pip, maybe fifteen. From a semitransparent plastic folder, a European-looking office supply, she took some pages slightly longer and narrower than American pages.

“So are you like a recruiter?” Pip asked. “You travel with the questionnaire?”

“Yes, I have authority,” Annagret said. “Or not authority, we reject authority. I’m one of the people who do this for the group.”

“Is that why you’re here in the States? Is this a recruiting trip?”

“Annagret is a multitasker,” Martin said with a smile somehow both admiring and needling.

Annagret told him to leave her and Pip alone, and he went off in the direction of the living room, apparently still serenely unaware that Dreyfuss didn’t like having him around. Pip took the opportunity to pour herself a second bowl of cereal; she was at least putting a check mark in the nourishment box.

“Martin and I have a good relationship, except for his jealousy,” Annagret explained.

“Jealousy of what?” Pip said, eating. “Andreas Wolf?”

Annagret shook her head. “I was very close with Andreas, for a long time, but that’s some years before I knew Martin.”

“So you were really young.”

“Martin is jealous of my female friends. Nothing more threatens a German man, even a good man, than women being close friends with each other behind his back. It really upsets him, like it’s something wrong with how the world is supposed to be. Like we’re going to find out all his secrets and take away his power, or not need him anymore. Do you have this problem, too?”

“I’m afraid I tend to be the jealous party.”

“Well, this is why Martin is jealous of the Internet, because this is how I primarily communicate with my friends. I have so many friends I haven’t even met—real friends. Email, social media, forums. I know Martin sometimes watches pornography, we don’t have secrets from each other, and if he didn’t watch it he probably would be the only man in Germany who didn’t—I think Internet pornography was designed for German men, because they like to be alone and control things and have fantasies of power. But he says he only watches it because I have so many female Internet friends.”

“Which of course may just be porn for women,” Pip said.

“No. You only think that because you’re young and maybe don’t need friendship so much.”

“So do you ever think about just going with girls instead?”

“It’s pretty terrible right now in Germany with men and women,” Annagret said, which somehow amounted to a no.

“I guess I was just trying to say that the Internet is good at satisfying needs from a distance. Male or female.”

“But women’s need for friendship is genuinely satisfied on the Internet, it’s not a fantasy. And because Andreas understands the power of the Internet, how much it can mean for women, Martin is jealous of him also—because of that, not because I was close with Andreas in the past.”

“Right. But if Andreas is the charismatic leader, then he’s the guy with the power, which to me makes it sound like he’s just like all the other men, in your opinion.”

Annagret shook her head. “The fantastic thing about Andreas is he knows the Internet is the greatest truth device ever. And what does it tell us? That everything in the society actually revolves about women, not men. The men are all looking at pictures of women, and the women are all communicating with other women.”

“I think you’re forgetting about gay sex and pet videos,” Pip said. “But maybe we can do the questionnaire now? I’ve kind of got a boy upstairs waiting for me, which is why I’m kind of just wearing a bathrobe with nothing underneath it, in case you were wondering.”

“Right now? Upstairs?” Annagret was alarmed.

“I thought it was just going to be a quick questionnaire.”

“He can’t come back another night?”

“Really trying to avoid that if I can.”

“So go tell him you only need a few minutes, ten minutes, with a girlfriend. Then you don’t have to be the jealous one for a change.”

Here Annagret winked at her, which seemed a real feat to Pip, who was no good at winking, winks being the opposite of sarcasm.

“I think you’d better take me while you’ve got me,” she said.

Annagret assured her that there were no right or wrong answers to the questionnaire, which Pip felt couldn’t possibly be true, since why bother giving it if there were no wrong answers? But Annagret’s beauty was reassuring. Facing her across the table, Pip had the sense that she was being interviewed for the job of being Annagret.

“Which of the following is the best superpower to have?” Annagret read. “Flying, invisibility, reading people’s minds, or making time stop for everyone except you.”

“Reading people’s minds,” Pip said.

“That’s a good answer, even though there are no right answers.”

Annagret’s smile was warm enough to bathe in. Pip was still mourning the loss of college, where she’d been effective at taking tests.

“Please explain your choice,” Annagret read.

“Because I don’t trust people,” Pip said. “Even my mom, who I do trust, has things she doesn’t tell me, really important things, and it would be nice to have a way to find them out without her having to tell me. I’d know the stuff I need to know, but she’d still be OK. And then, with everyone else, literally everyone, I can never be sure of what they’re thinking about me, and I don’t seem to be very good at guessing what it is. So, it’d be nice to be able to just dip inside their heads, just for like two seconds, and make sure everything’s OK—just be sure that they’re not thinking some horrible thought about me that I have no clue about—and then I could trust them. I wouldn’t abuse it or anything. It’s just so hard not to ever trust people. It makes me have to work so hard to figure out what they want from me. It gets to be so tiring.”

“Oh, Pip, we hardly have to do the rest. What you’re saying is fantastic.”

“Truly?” Pip smiled sadly. “You see, even here, though, I’m wondering why you’re saying that. Maybe you’re just trying to get me to keep doing the questionnaire. For that matter, I’m also wondering why you care so much about my doing it.”

“You can trust me. It’s only because I’m impressed with you.”

“You see, but that doesn’t even make any sense, because I’m actually not very impressive. I don’t know all that much about nuclear weapons, I just happened to know about Israel. I don’t trust you at all. I don’t trust you. I don’t trust people.” Pip’s face was growing hot. “I should really go upstairs now. I’m feeling bad about leaving my friend there.”

This ought to have been Annagret’s cue to let her go, or at least to apologize for keeping her, but Annagret (maybe this was a German thing?) seemed not very good at taking cues. “We have to follow the form,” she said. “It’s only a form, but we have to follow it.” She patted Pip’s hand and then stroked it. “We’ll go fast.”

Pip wondered why Annagret kept touching her.

“Your friends are disappearing. They don’t respond to texts or Facebook or phone. You talk to their employers, who say they haven’t been to work. You talk to their parents, who say they’re very worried. You go to the police, who tell you they’ve investigated and say your friends are OK but living in different cities now. After a while, every single friend of yours is gone. What do you do then? Do you wait until you disappear yourself, so you can find out what happened to your friends? Do you try to investigate? Do you run away?”

“It’s just my friends who are disappearing?” Pip said. “The streets are still full of people my age who aren’t my friends?”

“Yes.”

“Honestly, I think I’d go see a psychiatrist if this happened to me.”

“But the psychiatrist talks to the police herself and finds out that everything you said is true.”

“Well, then, at least I’d have one friend—the psychiatrist.”

“But then the psychiatrist herself disappears.”

“This is a totally paranoid scenario. That is like something out of Dreyfuss’s head.”

“You wait, investigate, or run away?”

“Or kill myself. How about kill myself?”

“There are no wrong answers.”

“I’d probably go live with my mom. I wouldn’t let her out of my sight. And if she somehow disappeared anyway, I’d probably kill myself, since by then it would be obvious that having any connection to me wasn’t good for a person’s health.”

Annagret smiled again. “Excellent.”

“What?”

“You’re doing very, very well, Pip.” She reached across the table and put her hands, her hot hands, on Pip’s cheeks.

“Saying I’d kill myself is the right answer?”

Annagret took her hands away. “There are no wrong answers.”

“That sort of makes it harder to feel good about doing well.”

“Which of the following have you ever done without permission: break into someone’s email account, read things on someone’s smartphone, search someone’s computer, read someone’s diary, go through someone’s private papers, listen to a private conversation when someone’s phone accidentally dials you, obtain information about someone on false pretenses, put your ear to a wall or door to listen to a conversation, and the like.”

Pip frowned. “Am I allowed to skip a question?”

“You can trust me.” Annagret touched her hand yet again. “It’s better that you answer.”

Pip hesitated and then confessed: “I’ve been through every scrap of paper my mother owns. If she had a diary, I would have read it, but she doesn’t. If she had an email account, I would have broken into it. I’ve gone online and searched every database I can think of. I don’t feel good about it, but she won’t tell me who my father is, she won’t tell me where I was born, she won’t even tell me what her real name is. She says she’s doing it for my protection, but I think the danger is only in her head.”

“These are things you need to know,” Annagret said gravely.

“Yes.”

“You have a right to know them.”

“Yes.”

“Do you understand that these are things the Sunlight Project can help you find out?”

Pip’s heart began to race, in part because this had not, in fact, occurred to her before, and the prospect was frightening, but mainly because she sensed that a real seduction was kicking into gear now, a seduction to which all of Annagret’s touchings had merely been a prelude. She took her hand away and hugged herself nervously.

“I thought the Project was about corporate and national security secrets.”

“Yes, of course. But the Project has many resources.”

“So I could just, like, write to them and ask for the information?”

Annagret shook her head. “It isn’t a private detection agency.”

“But if I actually went and did an internship.”

“Yes, of course.”

“Well, that’s interesting.”

“Something to think about, ja?”

“Ja-ah,” Pip said.

“You’re traveling in a foreign country,” Annagret read, “and one night the police come to your hotel room and arrest you as a spy, even though you haven’t been spying. They take you to the police station. They say that you may make one call that they will listen to both sides of. They warn you that anyone you call will also be under suspicion of spying. Whom do you call?”

“Stephen,” Pip said.

There was a flicker of disappointment in Annagret’s face. “This Stephen? The Stephen here?”

“Yes, what’s wrong with that?”

“Forgive me, but I thought you would say your mother. You’ve mentioned her in every other answer so far. She’s the only person you trust.”

“But that’s only trust in a deep way,” Pip said. “She’d go insane with worry, and she doesn’t know anything about how the world works, and so she wouldn’t know who to call to help me. Stephen would know exactly who to call.”

“To me he seems a bit weak.”

“What?”

“He seems weak. He’s married to that angry, controlly person.”

“Yes, I know, his marriage is unfortunate—believe me, I know.”

“You have feelings for him!” Annagret said with dismay.

“Yes, I do, so what?”

“Well, you didn’t tell me. We’re telling each other everything, on the sofa, and you didn’t tell me this.”

“You didn’t tell me you used to sleep with Andreas Wolf!”

“Andreas is a public person. I have to be careful. And that’s many years ago now.”

“You talk about him like you’d do it again in a heartbeat.”

“Pip, please,” Annagret said, seizing her hands. “Let’s not fight. I didn’t know you had feelings for Stephen. I’m sorry.”

But the wound the word weak had inflicted was hurting Pip more now, not less, and she was aghast to realize how much personal data she’d already surrendered to a woman so confident of her beauty that she could fill her face with metal and chop her hair (so it looked) with lawn clippers. Pip, who had no grounds for such confidence, snatched her hands away and stood up and noisily dropped her cereal bowl in the sink. “I’m going upstairs now—”

“No, we still have six questions—”

“Because I’m obviously not going to South America, and I don’t trust you one bit, not the tiniest bit, and so why don’t you and your masturbating boyfriend go down to L.A. and squat in somebody else’s house and give your questionnaire to somebody who’s into somebody stronger than Stephen. I don’t want you in our house anymore, and neither does anybody else. If you had any respect for me, you would have seen I didn’t even want to be here now.”

“Pip, please, wait, I’m really, really sorry.” Annagret did seem genuinely distressed. “We don’t have to do any more questions—”

“I thought it was a form we had to follow. Had to, had to. God, I’m stupid.”

“No, you’re really smart. I think you’re fantastic. I think only maybe your life revolves too much about men, a little bit, right now.”

Pip stared in amazement at this fresh insult.

“Maybe you want a female friend who’s something older but used to be so much like you.”

“You were never like me,” Pip said.

“No, I was. Sit down, please, ja? Talk with me.”

Annagret’s voice was so silky and commanding, and her insult had cast such humiliating light on Jason’s presence in Pip’s bedroom, that Pip almost obeyed her and sat down. But when she was gripped by her distrust of people it became physically unbearable to stay with them. She fled down the hallway, hearing the scrape of a chair behind her, the sound of her name being called.

On the second-floor landing, she paused to seethe. Stephen was weak? She thought about men too much? That is so nice. That really makes me feel good about myself.

Behind Stephen’s door, the marital fighting had stopped. Pip very quietly moved closer to it, away from the sound of basketball downstairs, and listened. Before long, there came a creak of a bedspring, and then an unmistakable whimpering sigh, and she understood that Annagret was right, that Stephen was weak, he was weak; and yet there was nothing wrong with a husband and a wife having sex. Hearing it and picturing it and being excluded from it filled Pip with a desolation that she had only one means of assuaging.

She took the rest of the stairs two at a time, as if shaving five seconds off her ascent could make up for half an hour’s absence. Outside her door, she composed her face into an expression of sheepish apology. It was a face she’d used a thousand times on her mother, to reliably good effect. She opened the door and peeked in, wearing the look.

The lights were on and Jason was in his clothes again, sitting on the edge of the bed, texting intently.

“Psst,” Pip said. “Are you horribly mad at me?”

He shook his head. “It’s just I told my sister I’d be home by eleven.”

The word sister dispelled much of the apology from Pip’s face, but Jason wasn’t looking at her anyway. She went in and sat down by him and touched him. “It’s not eleven yet, is it?”

“It’s eleven twenty.”

She put her head on his shoulder and her hands around his arm. She could feel his muscles working as he texted. “I’m sorry,” she said. “I can’t explain what happened. I mean, I can, but I don’t want to.”

“You don’t have to explain. I kind of knew it anyway.”

“Knew what?”

“Nothing. Never mind.”

“No, what, though? What did you know?”

He stopped texting and stared at the floor. “It’s not like I’m so normal myself. But relatively speaking—”

“I want to make normal love with you. Can’t we still do that? Even just for half an hour? You can tell your sister you’ll be home a little late.”

“Listen. Pip.” He frowned. “Is that your real name, by the way?”

“It’s what I call myself.”

“Somehow it doesn’t seem like I’m talking to you when I use it. I don’t know … ‘Pip.’ ‘Pip.’ It doesn’t sound … I don’t know …”

The last traces of apology drained from her face, and she took her hands away from him. She knew she had to resist an outburst, but she couldn’t resist it. The best she could do was keep her voice low.

“OK,” she said. “So you don’t like my name. What else don’t you like about me?”

“Oh, come on. You’re the one who left me up here for an hour. More than an hour.”

“Right. While your sister was waiting for you.”

Speaking the word sister again was like tossing a match into an oven full of unlit gas, the ready-to-combust anger that she walked around with every day; there was a kind of whoosh inside her head.

“Seriously,” she said, heart pounding, “you might as well tell me everything you don’t like about me, since we’re obviously never going to fuck, since I’m not normal enough, although what’s so abnormal about me I could use a little help in understanding.”

“Hey, come on,” Jason said. “I could have just left.”

The note of self-righteousness in his voice set fire to a larger and more diffuse pool of the gas, a combustible political substance that had seeped into her from her mother and then from certain college professors and certain gross-out movies and now also from Annagret, a sense of the unfairness of what one professor had called the anisotropy of gendered relationships, wherein boys could camouflage their objectifying desires with the language of feelings while girls played the boys’ game of sex at their own risk, dupes if they objectified and victims if they didn’t.

“You didn’t seem to mind me when your dick was in my mouth,” she said.

“I didn’t put it there,” he said. “And it wasn’t there long.”

“No, because I had to go downstairs and get a condom so you could stick it inside me.”

“Wow. So this is all me now?”

Through a haze of flame, or hot blood, Pip’s eyes fell on Jason’s handheld device.

“Hey!” he cried.

She jumped up and ran to the far side of the room with his device.

“Hey, you can’t do that,” he shouted, pursuing her.

“Yes I can!”

“No, you can’t, it’s not fair. Hey—hey—you can’t do that!”

She wedged herself underneath the child’s writing desk that was her only piece of furniture and faced the wall, bracing her leg on a desk leg. Jason tried to pull her out by the belt of her robe, but he couldn’t dislodge her and was apparently unwilling to get more violent than this. “What kind of freak are you?” he said. “What are you doing?”

Pip touched the device’s screen with shaking fingers.

“Fuck, fuck, fuck,” Jason said, pacing behind her. “What are you doing?”

She pawed the screen and found the next thread.

She slumped to one side, put the device on the floor, and gave it a push in Jason’s direction. Her anger had burned off as quickly as it had ignited, leaving ashen grief behind.

“It’s only the way some of my friends talk,” Jason said. “It doesn’t mean anything.”

“Please go away,” she said in a small voice.

“Let’s start over. Can we just, like, reboot? I’m really sorry.”

He put a hand on her shoulder, and she recoiled. He took the hand away.

“OK, look, let’s talk tomorrow, though, OK?” he said. “This was obviously the wrong night for both of us.”

“Just go away now, please.”

Renewable Solutions didn’t make or build or even install things. Instead, depending on the regulatory weather (not climate but weather, for it changed seasonally and sometimes seemingly hourly), it “bundled,” it “brokered,” it “captured,” it “surveyed,” it “client-provided.” In theory, this was all very worthy. America put too much carbon into the atmosphere, renewable energy could help with that, federal and state governments were forever devising new tax inducements, the utilities were indifferent-to-moderately-enthusiastic about greening their image, a gratifyingly non-negligible percentage of California households and businesses were willing to pay a premium for cleaner electricity, and this premium, multiplied by many thousands and added to the money flowing from Washington and Sacramento, minus the money that went to the companies that actually made or installed stuff, was enough to pay fifteen salaries at Renewable Solutions and placate its venturecapitalist backers. The buzzwords at the company were also good: collective, community, cooperative. And Pip wanted to do good, if only for lack of better ambitions. From her mother she’d learned the importance of leading a morally purposeful life, and from college she’d learned to feel worried and guilty about the country’s unsustainable consumption patterns. Her problem at Renewable Solutions was that she could never quite figure out what she was selling, even when she was finding people to buy it, and no sooner had she finally begun to figure it out than she was asked to sell something else.

At first, and in hindsight least confusingly, she’d sold powerpurchase agreements to small and midsize businesses, until a new state regulation put an end to the outrageous little cut that Renewable Solutions took of those. Then it was signing up households in potential renewable energy districts; each household earned Renewable Solutions a bounty paid by some shadowy third party or parties that had created an allegedly lucrative futures market. Then it was giving residents of progressive municipalities a “survey” to measure their level of interest in having their taxes raised or their municipal budgets rejiggered to switch over to renewables; when Pip pointed out to Igor that ordinary citizens had no realistic basis for answering the “survey” questions, Igor said that she must not, under any circumstances, admit this to the respondents, because positive responses had cash value not only for the companies that made stuff but also for the shadowy third parties with their futures market. Pip was on the verge of quitting her job when the cash value of the responses went down and she was shifted to solar renewable energy certificates. This had lasted six relatively pleasant weeks before a flaw in the business model was detected. Since April, she’d been attempting to sign up South Bay subdivisions for waste-energy micro-collectives.

Her associates in consumer outreach were flogging the same crap, of course. The reason they outperformed her was that they accepted each new “product” without trying to understand it. They got behind the new pitch wholeheartedly, even when it was risible and/or made no sense, and then, if a prospective customer had trouble understanding the “product,” they didn’t vocally agree that it sure was difficult to understand, didn’t make a good-faith effort to explain the complicated reasoning behind it, but simply kept hammering on the written pitch. And clearly this was the path to success, and it was all a double disillusionment to Pip, who not only felt actively punished for using her brain but was presented every month with fresh evidence that Bay Area consumers on average responded better to a rote and semi-nonsensical pitch than to a well-meaning saleswoman trying to help them understand the offer. Only when she was allowed to work on direct-mail and social-media outreach did her talents seem less wasted; having grown up with no television, she had good language skills.

Today being a Monday, she was telephonically harassing the many 65+s who didn’t use social media and hadn’t responded to the company’s direct-mail bombardment of a Santa Clara County development called Rancho Ancho. Micro-collectives only worked if you got near-total community buy-in, and a community organizer couldn’t be dispatched before a fifty percent response rate was achieved; nor could Pip earn any “outreach points,” no matter how much work she’d done.

She put on her headset and forced herself to look at her call sheet again and cursed the self she’d been an hour earlier, before lunch, because this earlier self had cherry-picked the sheet, leaving the names GUTTENSCHWERDER, ALOYSIUS and BUTCAVAGE, DENNIS for after lunch. Pip hated the hard names, because mispronouncing them immediately alienated the consumer, but she gamely clicked Dial. A man at the Butcavage residence answered with a gruff hello.

“Hiiiiii,” she said in a sultry drawl into which she’d learned to inject a note of apology, of shared social discomfort. “This is Pip Tyler, with Renewable Solutions, and I’m following up on a mailing we sent you a few weeks ago. Is this Mr. Butcavage?”

“Boocavazh,” the man corrected gruffly.

“So sorry, Mr. Boocavazh.”

“What’s this about?”

“It’s about lowering your electric bill, helping the planet, and getting your fair share of state and federal energy tax credits,” Pip said, although in truth the electric-bill savings were hypothetical, waste energy was environmentally controversial, and she wouldn’t have been making this call if Renewable Solutions and its partners had any intention of giving consumers a large share of the tax benefits.

“Not interested,” Mr. Butcavage said.

“Well, you know,” Pip said, “quite a few of your neighbors have expressed strong interest in forming a collective. You might do a little asking around and see what they’re thinking.”

“I don’t talk to my neighbors.”

“Well, no, of course, I’m not saying you have to if you don’t want to. But the reason they’re interested is that your community has a chance to work together for cleaner, cheaper energy and real tax savings.”

One of Igor’s precepts was that any call in which the words cleaner, cheaper, and tax savings could be repeated at least five times would result in a positive response.

“What is it you’re selling?” Mr. Butcavage said a mite less gruffly.

“Oh, this is not a sales call,” Pip lied. “We’re trying to organize community support for a thing called waste energy. It’s a cleaner, cheaper, tax-saving way to solve two of your community’s biggest problems at once. I’m talking about high energy costs and solid-waste disposal. We can help you burn your garbage at clean, high temperatures and feed the electricity directly into the grid, at a potentially significant cost savings for you and real benefit to the planet. Can I tell you a little bit more about how it works?”

“What’s your angle?” Mr. Butcavage said.

“I beg your pardon?”

“Somebody’s paying you to call me when I’m trying to take a nap. What’s in it for them?”

“Well, basically we’re facilitators. You and your neighbors probably don’t have the time or the expertise to organize a waste-energy micro-collective on your own, and so you’re missing out on cleaner, cheaper electricity and certain tax advantages. We and our partners have the experience and the know-how to set you up for greater energy independence.”

“Yeah, but who pays you?”

“Well, as you may know, there’s an enormous amount of state and federal money available for renewable-energy initiatives. We take a share of that, to cover our costs, and pass the rest of the savings on to your community.”

“In other words, they tax me to pay for these initiatives, and maybe I get some of it back.”

“That’s an interesting point,” Pip said. “But it’s actually a little more complicated. In many cases, you’re not paying any direct tax to fund the initiatives. But you do, potentially, reap the tax benefits, and you get cleaner, cheaper energy, too.”

“Burning my garbage.”

“Yes, the new technology for that is really incredible. Super clean, super economical.” Was there any way to say tax savings again? Pip had never ceased to dread, in these calls, what Igor called the pressure point, but she now seemed to have reached it with Mr. Butcavage. She took a breath and said: “It sounds like this might be something you’re interested in learning more about?”

Mr. Butcavage muttered something, possibly “burn my own garbage,” and hung up on her.

“Yeah, bite me,” she said to the dead line. Then she felt bad about it. Not only had Mr. Butcavage’s questions been reasonable, he also had an unfortunate name and no friends in his neighborhood. He was probably a lonely person like her mother, and Pip felt helplessly compassionate toward anyone who reminded her of her mother.

Because her mother didn’t drive, and because she didn’t need a photo ID in a small community like Felton, and because the farthest she ever went from Felton was downtown Santa Cruz, her only official identification was her Social Security card, which bore the name Penelope Tyler (no middle name). To get this card, using a name she’d assumed as an adult, she would have had to present either a forged birth certificate or the original copy of her real birth certificate along with legal documentation of her name change. Pip’s repeated fine-toothed combings of her mother’s possessions had turned up no documents like these, nor any safe-deposit key, which led her to conclude that her mother had either destroyed the documents or buried them in the ground as soon as she had a new Social Security number. Somewhere, some county courthouse may have had a public record of her name change, but the United States contained a lot of counties, few of them put their records online, and Pip wouldn’t even have known what time zone to start looking in. She’d entered every conceivable combination of keywords into every commercial search engine and ended up with nothing but an acute appreciation of the limitations of search engines.

When Pip was very young, vague stories had satisfied her, but by the time she was eleven her questions had grown so insistent that her mother agreed to tell her the “full” story. Once upon a time, she said, she’d had a different name and a different life, in a state that wasn’t California, and she’d married a man who—as she discovered only after Pip was born—had a propensity to violence. He abused her physically, but he was very cunning about inflicting pain without leaving serious marks on her, and he was even more abusive psychologically. Soon she became a total hostage to his abuse, and she might have stayed married until he murdered her if he hadn’t been so enraged by Pip’s crying, as a baby, that she feared for Pip’s safety as well. She tried running away from him with Pip, but he tracked them down and abused her psychologically and brought them home again. He had powerful friends in their community, she couldn’t prove that he abused her, and she knew that even if she divorced him he would still get partial custody of Pip. And she couldn’t allow that. She’d married a dangerous person and could live with her own mistake, but she couldn’t put Pip at risk. And so, one night, while her husband was away on business, she packed a suitcase and boarded a bus and took Pip to a battered-wives shelter in a different state. The women at the shelter helped her assume a new identity and get a new, fake birth certificate for Pip. Then she boarded a bus again and took refuge in the Santa Cruz Mountains, where a person could be whoever she said she was.

“I did it to protect you,” she’d told Pip. “And now that I’ve told you the story, you have to protect yourself and never tell anyone else. I know your father. I know how enraged he must have been that I stood up for myself and took you from him. And I know that if he ever found out where you are, he would come and take you from me.”

Pip at eleven was profoundly credulous. Her mother had a long, thin scar on her forehead which came out when she blushed, and her front teeth had a gap between them and didn’t match the color of her other teeth. Pip was so sure that her father had smashed her mother’s face, and felt so sorry for her, that she didn’t even ask her if he had. For a while, she was too afraid of him to sleep alone at night. In her mother’s bed, with stifling hugs, her mother assured her that she was completely safe as long as she never told anyone her secret, and Pip’s credulity was so complete, her fear so real, that she kept the secret until well into her rebellious teen years. Then she told two friends, swearing both to secrecy, and in college she told more friends.

One of them, Ella, a homeschooled girl from Marin, reacted with a funny look. “That is so weird,” Ella said. “I feel like I’ve heard that exact story before. There’s a writer in Marin who wrote a whole memoir with basically that story.”

The writer was Candida Lawrence (also an assumed name, according to Ella), and when Pip tracked down a copy of her memoir she saw that it had been published years before her mother had told her the “full” story. Lawrence’s story wasn’t identical, but it was similar enough to propel Pip home to Felton in a cold rage of suspicion and accusation. And here was the really weird thing: when she laid into her mother, she could feel herself being abusive like her absent father, and her mother crumpled up like the abused and emotionally hostage-taken person she’d portrayed herself as being in her marriage, and so, in the very act of attacking the full story, Pip was somehow confirming its essential plausibility. Her mother sobbed revoltingly and begged Pip for kindness, ran sobbing to a bookcase and pulled a copy of Lawrence’s memoir from a shelf of more self-helpy titles where Pip would never have noticed it. She thrust the book at Pip like a kind of sacrificial offering and said it had been an enormous comfort to her over the years, she’d read it three times and read other books of Lawrence’s too, they made her feel less alone in the life she’d chosen, to know that at least one woman had gone through a similar trial and come out strong and whole. “The story I told you is true,” she cried. “I don’t know how to tell you a truer story and still keep you safe.”

“What are you saying,” Pip said with abusive calm and coldness. “That there is a truer story but it wouldn’t keep me ‘safe’?”

“No! You’re twisting my words, I told the truth and you have to believe me. You’re all I have in the world!” At home, after work, her mother let her hair escape its plaits into a fluffy gray mass, which now shook as she stood and keened and gasped like a very large child having a meltdown.

“For the record,” Pip said with even more lethal calm, “had you or hadn’t you read Lawrence’s book when you told me your story?”

“Oh! Oh! Oh! I’m trying to keep you safe!”

“For the record, Mom: are you lying about this, too?”

“Oh! Oh!”

Her mother’s hands waved spastically around her head, as if preparing to catch the pieces of it when it exploded. Pip felt a distinct urge to slap her in the face, and then to inflict pain in cunning, invisible ways. “Well, it’s not working,” she said. “I’m not safe. You have failed to keep me safe.” And she grabbed her knapsack and walked out the door, walked down their steep, narrow lane toward Lompico Road, beneath the stoically stationary redwoods. Behind her she could hear her mother crying “Pussycat” piteously. Their neighbors may have thought a pet had gone missing.

She had no interest in “getting to know” her father, she already had her hands full with her mother, but it seemed to her that he should give her money. Her $130,000 in student debt was far less than he’d saved by not raising her and not sending her to college. Of course, he might not see why he should pay anything now for a child whom he hadn’t enjoyed the “use” of, and who wasn’t offering him any future “use,” either. But given her mother’s hysteria and hypochondria, Pip could imagine him as a basically decent person in whom her mother had brought out the worst, and who was now peaceably married to someone else, and who might feel relieved and grateful to know that his long-lost daughter was alive; grateful enough to take out his checkbook. If she had to, she was even willing to offer modest concessions, the occasional email or phone call, the annual Christmas card, a Facebook friendship. At twenty-three, she was well beyond reach of his custody; she had little to lose and much to gain. All she needed was his name and date of birth. But her mother defended this information as if it were a vital organ that Pip was trying to rip out of her.

When her long, dispiriting afternoon of Rancho Ancho calls finally came to an end, at 6 p.m., Pip saved her call sheets, strapped on her knapsack and bike helmet, and tried to sneak past Igor’s office without being accosted.

“Pip, a word with you, please,” came Igor’s voice.

She shuffled back so he could see her from his desk. His Gaze glanced down past her breasts, which at this point might as well have had giant eights stenciled on them, and settled on her legs. She would have sworn they were like an unfinished sudoku to Igor. He wore exactly that frown of preoccupied problem-solving.

“What,” she said.

He looked up at her face. “Where are we with Rancho Ancho?”

“I got some good responses. We’re at, like, thirty-seven percent right now.”

He nodded his head from side to side, Russian style, noncommittal. “Let me ask you. Do you enjoy working here?”

“Are you asking me if I’d prefer to be fired?”

“We’re thinking of restructuring,” he said. “There may be an opportunity for you to use other skills.”