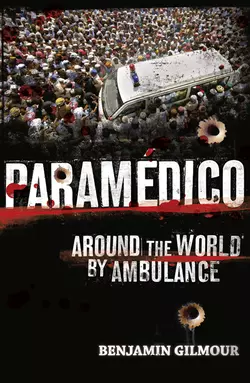

Paramédico

Paramédico

Benjamin Gilmour

Around the world by ambulance.Paramédico is a brilliant collection of adventures by Australian paramedic Benjamin Gilmour as he works and volunteers on ambulances around the world. From England to Mexico, and Iceland to Pakistan, Gilmour takes us on an extraordinary thrill-ride with his wild coworkers. Along the way he learns a few things, too, and shows us not only how precious life truly is, but how to passionately embrace it.

To the men, women and children working on ambulances around the world.

CONTENTS

COVER (#u50194e03-4df3-56da-b4aa-20568f8a29eb)

TITLE PAGE (#u28931fcb-8b44-5c9f-9a3e-86006f7eb664)

DEDICATION (#uca5b3bda-af55-509c-aecb-b666e0914606)

INTRODUCTION (#u2676c614-495e-5c17-9c1d-f66da8ad70cd)

OUTBACK AMBO – AUSTRALIA (#ud99971db-2085-58c7-9655-2ba0168ca4e3)

RUNNING WITH THE LEOPARD – SOUTH AFRICA (#ua0433f24-636f-5766-80a9-bb6886657cc7)

SHEIK, RATTLE AND ROLL – ENGLAND (#u06f620b6-4e17-5c99-b45b-ada2285b2fd8)

ALL QUIET! NEWS BULLETIN! – THE PHILIPPINES (#u9e869657-ff09-56c2-910c-320a1cce97d7)

DR AQUARIUS AND THE GYPSIES – MACEDONIA (#u2b2da4e4-0cb9-5277-a552-7b88131ba048)

ISLAND OF THE MONSTER WAVE – THAILAND (#litres_trial_promo)

A COUNTRY TO SAVE – PAKISTAN (#litres_trial_promo)

THE NAKED PARAMEDIC – ICELAND (#litres_trial_promo)

DEATH IN VENICE – ITALY (#litres_trial_promo)

A HULA SAVED MY LIFE – HAWAII (#litres_trial_promo)

THE CROSS OF FIRE – MEXICO (#litres_trial_promo)

AUTHOR NOTE (#litres_trial_promo)

GLOSSARY (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

BY THE SAME AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

COPYRIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#litres_trial_promo)

INTRODUCTION

From the day of its invention the ambulance has attracted a magnetic curiosity from humans around the world. This vehicle racing to the scene of accidents and illness demands attention. When you hear one coming, you turn. When you watch it pass you wonder, if only for a moment, where it might be going, who is inside and what horrific mishap the patient has suffered. After fifteen years spent in the back of ambulances I’ve come to realise that medics and paramedics are endlessly fascinating to the public.

But despite our appeal, the truth about us is largely hidden from view. It is hidden because, in the instant we drive past we have carried our secrets away, leaving nothing more than the wail of a siren. We are hidden because the usual depiction of paramedics on film and television is mostly a fantasy. The title of hero is forced upon us, and what is lost is who we really are.

Right now, as you read this, more than a hundred thousand ambulance medics in all manner of unusual and remote locations across the planet are responding to emergencies. They are scrambling under crashed cars, carrying the sick down flights of stairs, scooping up body parts after bombings, comforting the depressed, resuscitating near-dead husbands at the feet of hysterical wives, and stemming the blood-flow of gunshot victims in seedy back alleys. A good number too are just as likely to be raising an eyebrow at some ridiculous, trivial complaint their patient has considered life-threatening. Each of these medics could fill a book just like this one, with adventures many more extreme, dangerous and shocking than those recounted here.

My fascination with the lives of people from countries and cultures other than my own is driven by my ultimate desire to understand humanity. And so I travel at every opportunity to observe how people interact, and learn why they believe what they do, how they live and how they die and how they grieve. From the age of nineteen, during periods of leave each year, I have worked or volunteered with foreign ambulance services. Whether acting as a guest or consultant, I stayed sometimes for a month, other times more than a year. Every day it has been a privilege. There are few professions like that of an ambulance worker – we have a rare licence to enter the homes of complete strangers and bear witness to their most personal moments of crisis.

Globally, the make-up of ambulance crews is varied, though it’s generally agreed there are two models of pre-hospital care delivery – the Anglo-American model based on one or two paramedics per ambulance, or the Franco-German model where the job is performed by doctors and nurses. Over recent years, a number of Anglo-American systems have also introduced paramedic practitioners with skills that, until now, have been the strict domain of emergency physicians. Pre-hospital worker profiles also include drivers and untrained attendants who can still be found responding in basic transport ambulances across many developing countries. Since cases demanding advanced medical intervention represent only a small percentage of emergency calls, it would be a mistake to judge ambulance workers as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ solely on clinical ability. Consequently, I have chosen to explore the world of many ambulance workers, no matter where they are from or what their qualifications. It is true that ambulance medics are united by the unique challenges of their job. They are members of a giant family and they understand one another instantly. While the work may differ in its frequency, level of drama and cultural peculiarities, there is no doubt that medics the world over experience similar thrills and nightmares.

As a paramedic and traveller, I’ve enjoyed the company of my brothers and sisters in many exotic locations. I’ve lived with them, laughed with them and cried with them. And wherever it was I journeyed, my ambulance family not only showed me their way of life, they also unlocked for me the secret doors to their cities and the character of their people, convincing me that paramedics are the best travel guides one can hope to have.

More than a story about the sick and injured, Paramédico is about the places where I have worked and the people I have worked there with. It’s about the men and women who have remained a mystery to the world for long enough.

So, climb aboard, buckle up, and embark with me on these grand adventures by ambulance.

OUTBACK AMBO

Australia

For two weeks I have sat here in this fibro shack along the Newell Highway listening to the ceaseless drone of air-conditioning, waiting for the sick and injured to call me. Coursework for my paramedic degree is done and all my novels are read. Now I wait, occasionally wishing, with guilt, for some drama to occur, some crisis, no matter how small, anything to break the monotony of my posting.

From time to time my mother sends me a letter or her ginger cake wrapped in brown paper. For the second time today, I drive to the post office in my ambulance.

I’m stationed in Peak Hill in central New South Wales, a town some locals might consider their whole world. But to me, a nineteen-year-old city boy with an interest in surfing and clubbing, I am cast away, marooned, washed up in the stinking hot Australian outback.

‘Sorry, champ,’ says the post officer. ‘Nothing today.’

And so I drive my ambulance around the handful of quiet streets where nothing ever changes, where I rarely see a soul. Shutters are down, curtains drawn, doors shut. Where are they all, I wonder, these people who apparently know my every move?

I turn down towards the wheat silo and park, imagining how I would treat someone who had fallen from the top of it. After that I go to meet a flock of sheep with whom I’ve learnt to communicate. Much of it is non-verbal. We just stand there, the flock and I, face to face, staring quietly, contemplating what the other’s life must be like. Now and then we exchange simple sounds by way of call-and-response. Whenever I think I’ve gone mad I remind myself that most people talk freely to their pets without a second thought.

Earlier in the year, the Ambulance Service of New South Wales sent my whole class to remote corners of the state. I understood, of course, that in our vast country with its sparsely populated interior, everyone is equally entitled to pre-hospital care. Only problem is that few applications to the service are received from people living in the bush. Instead, young, degree-qualified city recruits from the eastern seaboard end up in one-horse towns.

As I entered the Club House Hotel in Caswell Street on my first night, twelve faces textured like the Harvey Ranges turned my way, looked me up and down taking in my stovepipe jeans, my combed hair and patterned shirt. As if my appearance was not out of place enough, I foolishly ordered a middy of Victoria Bitter and the room erupted in thigh-slapping laughter. Before I ran out, a walnut of a man nearest to me leant over to offer some local advice.

‘Out here, mate, it’s a schooner of Tooheys New, got it?’

I never went back to the pub, at least not socially. When called there in the ambulance for drunks fallen over, I was always greeted with the same row of men in the same position at the bar, like they had never gone home. It didn’t take me long to realise I’d need to find entertainment elsewhere.

In less than a month Kristy Wright, an actor playing the role of Chloe Richards on the evening soap Home & Away, has become the object of my affection. As the elderly will attest, a routine of the ordinary brings security of sorts, a familiar comfort, and Home & Away is just this for a lonely paramedic with too much time on his hands and not enough human company. Kristy is not particularly glamorous, nor is she Oscar material. Perhaps it’s her likeness to my first proper girlfriend, a ballerina who ran off to Queensland, married someone else, and broke my heart. Whatever the reason, I’m deeply smitten and make sure never to miss an episode.

For a small fee I have taken accommodation in the nurses’ quarters on the grounds of Peak Hill’s tiny brick hospital with its single emergency bed. Adjacent to the hospital lies the ambulance station consisting of a small office, a portable shed with air-conditioning and a garage containing an F100 and a Toyota 4x4 ambulance for difficult terrain. My new home next door is a freestanding weatherboard cottage, a little rundown but quaint nonetheless. Lodging at these nurses’ quarters initially sounded quite appealing to a young, single man, but the place never came with any nurses in it.

At 8 pm I ladle some lentil soup out of a giant pot I prepared earlier in the week, heating it up on the electric stove. After dinner, at 9 pm, I run the bath, making sure my blue fire-resistant jumpsuit is hanging by the door and my boots are standing to attention below, ready for the next job – if I ever live to see it, that is. Two slow weeks and I’m beginning to think they should close the ambulance station down before their assets rust away. The population plummeted a few years ago when Peak Hill’s gold mine hit the water table and ceased operations. Locals left behind would disagree, but maybe ambulance stations ought to come and go with the mines.

When the call finally comes it catches me off guard, just as I knew it would, cleaving me from a deep 4 am sleep.

‘Huh?’ I grunt into the phone. The dispatcher in the Dubbo control room 80 kilometres away sounds just as vague.

‘Okay, what we got here, let me see, ah, semi rollover on the Newell Highway six kilometres south of Peak Hill … well, that’s about all I have, mate … good luck with it.’

I hang up, slide out of bed in my jocks, splash my face at the bathroom sink, head to the door.

Keys, keys, ambulance keys. I teeter on the remains of sleep, trying to think of where I put the keys. When I throw my legs into the jumpsuit I’m relieved to hear them jingling in a pocket. My boots are on and I’m out.

The engine of the Ford springs to life, the V8 gives a mighty roar, a call to action. Adrenalin, like petrol charging through the lines, ignites me for the fight. I flick on the red flashing roof lights, the grill lights on the front, and then, as I skid onto the highway, I let the siren rip through the stillness. There’s not a car in sight, no one at all to warn of my approach, but this run is for the hell of it. I’m doing it because I can, because for two weeks I’ve been bored out of my brain and I’ll be damned if I won’t make the most of a genuine casualty call.

The Ford is a missile; eight cylinders of muscle thundering down the highway. In no time I cover the six kilometres, wishing the crash was further away for a longer drive. Last month it took me sixty minutes on the whistle travelling at speeds of 150 kilometres per hour to reach a child fallen off a horse at a remote property.

Up ahead a pair of stationary headlights in the middle of the road beam at me. They appear, at first, to be sitting higher than normal, but when I get closer I realise the semitrailer to which they belong has flipped upside down. It’s a most peculiar sight.

No one has motioned me to stop. In fact, there is no one about at all, not even Doug the policeman. Further down the road I spy another truck pulled up with its hazard lights on and assume this driver must have called the job in.

The motor of the upturned semi is still idling. It’s an eerie sound in the absence of any other. I decide that, for the purpose of making the scene safe and preventing an explosion, I ought to switch it off.

From what seems to have been the passenger side of the truck a steady stream of blood runs slowly to the shoulder of the road. The entire cabin of the semi is crushed and when I call out ‘Hello there!’ I don’t even get a grunt of acknowledgement.

This is my job, I remind myself. It falls on no one else. It is precisely my duty, without further delay, to climb underneath the overturned truck, attempt to turn off the ignition and ascertain the number and condition of its occupants.

With a small torch in hand, I get down on my chest and crawl into a narrow passage about a foot high with twisted metal and shattered glass all around, my head is turned on the side, oil and bitumen brush my cheek until I reach an opening in front of me. Here I’m able to lift my head up and take a look around. When I do this my heart jumps like a stung animal as I find myself face-to-face with the driver, his head pummelled into a mushy, shapeless mess, his mouth gaping wide and a single avulsed eye glaring at me. For the first time ever I am simply too startled to shriek or utter any sound whatsoever. Confined like this makes a rapid retreat difficult. Instead, I am frozen in horror, just as the driver’s face may have been in the moment before it was destroyed by his dashboard.

After a few seconds, when I regain a little composure, I reach up to the keys dangling in the ignition and turn off the engine. At the same time I see a photo of a woman and child, smiling at the camera, some birthday party. Perhaps it was the last image the man saw before exhaling his final breath.

Almost as slowly as I entered the cabin I extract myself and return to the ambulance, shaking ever so slightly, to give Dubbo control a report from the scene.

It takes Peak Hill’s SES Rescue Squad five hours to remove the driver’s body. Most of this is spent waiting for a crane to arrive from Parkes. I stand in the shadows clutching a white folded body bag, reluctant to join the rescue volunteers, all ex-miners and rough farmhands cursing and spitting and slapping each other on the back.

At the hospital, the nurse on duty has called in Peak Hill’s only doctor, a short Indian fellow, to sign the certificate. When I unzip the body bag and pull it back, all colour drains from the doctor’s face, his eyes roll into his head and he grips the wall to stop himself from passing out.

‘Doc may need to lie down for a while,’ I say to the nurse as she leaps forward to prevent him falling.

By the time I finish at the morgue the sun is high over the Harveys and I reverse the ambulance into the station, putting it to bed for another two weeks.

Most of Peak Hill’s indigenous population lives in what is still known as ‘the mission’, a handful of streets on the south side of town once run by missionaries. In comparison to many Aboriginal missions in the Australian outback, the houses are fairly tidy and the occupants give us little trouble. Except for Eddy and his extended family, that is. When things become too monotonous in Peak Hill one can always rely on Eddy to get pissed, flog his missus or end up unconscious in someone’s front yard. Empty port flagons line the hallway of his house, a house without a door and with every window smashed in. Half the floorboards have been torn up for firewood in the winter.

Jobs often come in spurts and on the day after the semi rollover I scoop Eddy onto the stretcher and cart him to the hospital for his weekly sobering-up. In straightforward cases like this I work alone, making sure to angle the rear-vision mirror onto the patient for visual observation. Occasionally, to be certain the victim doesn’t pass away unnoticed, I attach a cardiac monitor for its regular audible blipping. This way I can keep my eyes on the road ahead.

Longer journeys are a little trickier. For these I must evaluate a patient’s blood pressure every ten minutes or so by pulling over and climbing into the back. It is hardly ideal, but sometimes necessary when I’m unable to find a suitable or sober candidate to drive the ambulance for me. A strategy the service conceived many years ago was to recruit volunteer drivers from the community, people familiar with the names and location of distant cattle stations and remote dirt tracks.

Charlie, a hulk of a man with handlebar moustache and hearty belly laugh is the best on offer. Unfortunately his job as a long-haul coach driver means he’s rarely in town when I need him. Perhaps one day he will join the service full-time.

As for Lionel, Peak Hill’s only other volunteer officer, he is simply too crass to take anywhere at all. Unshaven, slouchy and barely able to complete the shortest string of words without adding expletives, Lionel is my last resort. Nonetheless, his job as the hospital caretaker means he torments me with racist, redneck tales and invitations to bi-monthly Ku Klux Klan gatherings held at secret locations in the Harvey Ranges. His open dislike of ‘boongs’ – a derogatory term for Aboriginal people – is another reason I don’t take him on jobs in the mission. Lionel’s most beloved pastime is ‘road kill popping’, which involves intentionally driving over bloated animals with his Ford Falcon in order to hear them ‘pop’ under the chassis. Worse still, less than a month after my arrival in Peak Hill, he snatched a snow-white cooing dove from the eaves of the ambulance station and ripped its head off, whining about the ‘pests’ inhabiting the hospital rafters. This callous act prompted me to slam the door in his face.

When my family drives up from Sydney to pay me a visit I take them to the Bogan River, just out of town. It’s a sorry little waterway but there are several picnic spots to choose from. In the shade of a snow gum we spread out a tartan blanket. My mum unwraps her tuna sandwiches and pours out the apple juice while my dad reflects on the subjects of solitude, meditation, Jesus in the desert. My sister and brothers are not normally so quiet and I sense everyone feels a bit sorry for me, as if I have some kind of incurable disease, all because I’m stuck here in Peak Hill.

Later that night, as no volunteer drivers are available, my dad offers to join me on a call to the main street. He’s still tying the laces of his Dunlop Volleys in the front seat when I pull up at the address. Above the newsagent, in a room devoid of any furniture, an eighteen-year-old male is hyperventilating and gripping his chest. The teenager is morbidly obese for his age, thanks to antidepressants and a diet of potato chips and energy drinks. What he is still doing in this town, estranged from his parents, roaming about jobless and alone, is beyond me.

‘My heart,’ he moans.

As I take a history and connect the cardiac monitor, I relish this rare moment. Doesn’t every son secretly dream of impressing his father with knowledge and skill? Our patient hardly requires expert emergency attention, but Dad observes my every move and his face is beaming.

Suspecting the patient has once again consumed too many Red Bulls, I offer him a trip to hospital and he nods. If I were him I too would rather spend my evening with the night-nurse than sit here alone. Once loaded up, I throw Dad the ambulance keys and give him a wink.

‘Wanna drive? Someone’s got to keep him company.’

For a second or two Dad stands there looking like a kid on Christmas morning.

No one visits me after that for the rest of my time in Peak Hill, but six months in I’m less concerned about isolation. Routines I’ve constructed help the time pass. I’ve also begun to feel the subtle tension that simmers below the surface of every country town, the whispering voices from unseen faces and the contradiction of personal privacy coupled with the compulsive curiosity to know the business of others. A lady in the grocery store last week was able to recite to me my every movement for three consecutive days: what time I left the station in the ambulance, where I drove to and what I did there. Sheep are dumb animals, she told me. My efforts to communicate with them at Jim Bolan’s property were futile and stupid. I was speechless. Never on any visit to my fleecy friends had I seen another human being. Perhaps the sheep themselves were dobbing me in? Back in Sydney, where people live side by side and on top of one another, a person can saunter about naked in the backyard and no one pays the least bit of notice. Those who imagine they will find some kind of seclusion in a country retreat should think again.

It’s August and my cases last month entailed an old man dead in his outhouse for at least a fortnight, a diabetic hypo to whom I administered Glucagon by subcutaneous injection and a motorcyclist with a broken femur on the road to Tullamore.

After browsing the internal vacancies around the state, I decide to apply for Hamilton in Newcastle. One of the controllers in Dubbo is a keen surfer like me and whenever he calls for a job we joke about starting a Western Division surfing team. I regret telling him about the Newcastle position because he immediately says he will go for it too, his length of service giving him a clear advantage.

As steady as I may be going in Peak Hill, the month ends with an accident that changes everything, an accident forcing me to leave town for my own safety.

At 10 pm on a Friday night I am in bed, lying awake in a silence one never hears in Sydney, imagining the wild time my friends are having there, bar-hopping around Darlinghurst and Surry Hills, seeing bands and DJs, laughing and flirting with girls.

When the phone rings, I jump back into the cold, dark room, sit bolt upright, snatching the receiver.

‘Peak Hill Station.’

‘Yeah mate, let’s see … some kid hit by a semi on the main street, says it’s near the service station. I’ll sort you out some back-up from Dubbo. They’re just finishing a transfer so it might be an hour or so, maybe forty-five – if they fang it. Booked 10.01, on it 10.02. Good luck.’

No matter how many truck drivers Doug the policeman books for speeding through the main street, few semitrailers slow down much. They have a tight schedule and Peak Hill is just another blink-and-you-miss-it town clinging to the highway.

As it turns out, the fourteen-year-old Aboriginal boy lying in the gutter has only been ‘clipped’ by the semitrailer, a hit-and-run, although I suspect the driver wouldn’t have noticed. A crowd from the mission has quickly formed and they urge me to hurry as I retrieve my gear.

‘C’mon brudda, ya gotta help tha poor fella, he ain’t in a good way mister medic.’

Relieved to find the boy conscious, I put him in a neck brace and begin a quick head-to-toe examination to ascertain his injuries. As I’m doing this I feel a hand squeeze my buttocks, more than one hand, in fact, until a good many are occupied with my bum cheeks. I look around but the crowd encircling me is too dense to identify a particular culprit. I wonder where Doug the policeman is, he always seems to arrive well after a drama is over.

The crowd shuffles back half a foot when I ask for some room, but pushes in again when I take a blood pressure reading. A second time I feel the hands, this time squeezing and caressing my buttocks with renewed enthusiasm, one of them even giving me an affectionate little slap. Such a thing is most distracting in emergency situations. Moreover, it’s shameless sexual harassment. I grab my portable radio, calling for urgent police assistance. That should wake Doug up, I think to myself. Again I demand the onlookers move away, but my request is ignored.

‘Listen brudda,’ says an elder among the group. ‘We don’t trust you whitefellas, we gotta watch you, make sure you do us a good job, you know wad I mean?’

Finally Doug turns up, huffing and puffing and waving at the crowd to move on. Reluctantly they do, now giving me space to load the patient. Doug offers to drive the ambulance to the hospital and I call off my back-up from Dubbo as the boy seems to have suffered little more than minor abrasions.

Early the next morning I am woken by the sound of a car with holes in the muffler going up and down the dirt road beside the nurses’ quarters. Crouching low, I crawl in my underwear to the kitchen where I’m able to peek out between the lace curtains on the window above the sink. Idling on the grass outside my place is a beaten-up, cream-coloured Datsun packed with Aboriginal girls.

‘Shit,’ I curse to myself. From my position at the window I can make out their conversation as they speculate on my whereabouts.

‘He ain’t come out from that house all morning, I reckon he in there, he in there, I’m telling ya.’

‘Maybe he gone walkabout.’

‘He ain’t gone walkabout! Ambo guys don’t go walkabout, they gotta be ready, you know, READY!’

‘Yeah, and we seen two ambulance in that big shed, means he in there, he in there for sure!’

Not wanting to get caught undressed, I crab-crawl my way back to the bedroom and throw on my uniform, complete with all its formal trimmings. Maybe if I wear the tie and jacket with gold buttons down the front and speak with a firm tone I can scare off my stalkers. By the time I psych myself up to step out and challenge the girls – a butter knife in my pocket for reassurance – the Datsun does a donut, whipping up a cloud of dirt and farts off towards the highway. The girls catcall before the car shudders over the cattle grate at the end of the track and disappears.

I phone Doug and explain the situation.

‘Yeah, I heard,’ he says.

‘Heard what?’

‘The blackfellas are a bit upset with you.’

‘Me? Why? I did fine with that kid last night.’

‘Sure you did but you also got yourself a big problem in the process, mate. Those Koori chicks are trouble and you’re the talk of the mission today. Heard they even got a special name for you, what is it again? Ah, Romeo! That’s it!’

‘Romeo?’

‘Romeo, as in Romeo and Juliet, you know, that movie that’s just come out?’

Baz Luhrmann’s sexy contemporary interpretation of the Shakespearean classic had recently done good business at the Australian box office. Even Aboriginal kids in Peak Hill, miles from any cinema screen, knew about it. Unfortunately I didn’t look anything like Leonardo DiCaprio. How could the girls have come to such a comparison based on the quality of my arse alone?

‘Take it from me mate, whatever you do, don’t be going down the mission on a job, understand? You’ll either be set upon by the women or a jealous bloke will glass your throat.’

He paused for a moment. ‘Actually, you got to get out of here.Those girls won’t let up until they pin you down. Literally.’

‘But Doug, you’re a cop for crying out loud!’

‘Come on. Cops can’t touch no blackfella these days, let alone a female of the species. You know that. Sorry to tell you this, mate, you’re on your own.’

Never have I covered the 20-metre distance between the nurses’ quarters and the ambulance station in less time. Whatever door I pass through, I make certain it’s bolted behind me. Despite Doug the policeman’s fear-mongering, if a call comes in for the mission I have every intention of making an official request for his assistance. This way he cannot, by law, refuse to help me. The idea of driving anywhere near the southern part of town has put me on a knife’s edge. What’s to say a bitter indigenous bloke down there doesn’t ring triple-0, fake some illness and jump up to strangle me with my own stethoscope?

My hopes of being nothing more than a passing interest are dashed the following day with the approach of the Datsun again at 10 am. It circles the ambulance station five or six times, coughing and backfiring. The car eventually skids to a stop and one of the girls gets out and peers through the window to see if I’m inside. Lying motionless behind the lounge, hiding for a good ten minutes, I wonder what my job has become. There is no question in my mind how different a situation like this would be if I were a female paramedic and my stalkers were male.

The Bogan Times comes out on Monday and ‘Peak Hill’s Romeo’ is front-page news: ‘Local Ambo Talk of the Town!’

Management in Dubbo are concerned. My wellbeing is under threat and the service has a responsibility for my safety next time there’s a call to the Peak Hill mission.

Within a week I get surprising news. Out of all the applications for Hamilton Station, mine has been selected and I’m offered the position. With little hesitation I accept. Although I’m told the merit of my application won me the position, I’m unconvinced. My transfer takes effect immediately, which rarely happens. It seems obvious to me that the Newcastle job offer and my report of sexual harassment are no coincidence at all.

On the afternoon I get my transfer letter the Koori girls arrive again for their daily patrol. This time I lounge on the verandah in my underwear and give them a wave. Having eluded them for a fortnight, the girls scream in delight. A moment later the Datsun stalls and skids into a ditch. As the girl driving curses and tries starting it again, her accomplices lean out of the windows, yelling at the top of their voices.

‘Hey, white boy!’

‘Love your arse, white boy!’

‘How about it, white boy!’

None of them actually leaves the car, and I sense for the first time they are too shy to come any closer.

‘Love you, white boy!’

‘Come and see us, white boy!’

Finally the engine splutters back to life. Before they pull onto the track again I make sure to blow them a kiss.

‘Thank you, girls! Thank you!’ I call after them.

The Datsun tumbles down and away in a flurry of hooting horns, wolf-whistles and flailing arms. When the dust settles and the road is quiet again, I’m overcome with shame for my unfounded anxieties. How harmless these girls were in reality, making the most of their life in this drab, nowhere town. A little innocent fun is all they ever wanted. Having finally lured the white boy medic from his house, I know in my heart they won’t be back.

But neither will I.

RUNNING WITH THE LEOPARD

South Africa

Sleep will never visit me, lying on a paramedic’s black leather lounge, imagining the lethal violence steaming across the city. Any moment now the phone will ring. My stomach is taut, turning with readiness, primed for action. Few men and women have slept, truly slept I mean, waiting for emergencies on a Jo’burg Friday night. Even Neil Rucker – The Leopard – is wide awake behind shut eyes.

A paramedic employed by Netcare 911, South Africa’s second biggest ambulance service, The Leopard drives a late-model Audi and is permitted to work from home. The Leopard’s modest red-brick house lies in a suburb close enough to the tough suburbs of Hillbrow and Berea for a quick response but far enough away to avoid bodies on his lawn in the morning.

‘Like to be around my cats,’ he says, pointing to a gallery of framed prints depicting handsome leopards crouching on the veld. Others recline on the boughs of trees yawning at sunset. The Leopard’s colleagues told me earlier in the day Rucker’s nickname was inspired not only by his passion for the big cat, but his own cunning intelligence and skill, in particular his masterful intubation of patients with severe oropharyngeal trauma. He’s got the veteran’s look too – shaved head, a few good scars, eyes narrow and a little icy.

The Leopard lights some lotus incense with his Zippo and puts on a CD of meditation music. Slow synthesizers complement the sound of trickling from a water feature standing among indoor ferns. Despite the atmosphere of an Asian spa I still can’t unwind. When the first call comes in I’m up like a jack-in-the-box.

Before we head off, The Leopard ducks into his bathroom and pulls the door shut. When he comes out he is wired-up, sniffing and rubbing his nose in the way a person would after snorting cocaine. I pretend not to notice. He may be suffering allergies, sinus problems.

‘Here, put this on,’ he says, passing me a bulletproof vest. It sits on my shoulders like a sack of rocks.

‘Wow, it’s heavy …’

‘Ja, it’s inlaid with ceramic. Don’t worry, we won’t be going swimming,’ he says dryly.

The Leopard pops some chewing gum in his mouth, punches the air with his fists and grabs the car keys off the table. Seconds later we are rocketing along roads drenched in the apocalyptic orange light of street lamps, the engine of the Audi revving wildly, my body pushed back in the seat as The Leopard clocks 200 kilometres per hour into town.

Held over a week in a classroom at Witwatersrand – the university attached to Johannesburg General Hospital – the globally recognised Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) course is meant to be intense. Conceived by the American College of Surgeons, in South Africa it is taught by those with perhaps the most experience in trauma anywhere in the world. Even with levels of violence in slow decline since the end of apartheid, Johannesburg makes no attempt to shake off its image as one of the most dangerous cities on earth. In 2008, Time magazine published figures showing an average of fifty-two murders occur in Johannesburg every twenty-four hours. This round-the-clock blunt and penetrating trauma ensures Jo’burg is to medics what Milan is to fashion designers. From Europe, Asia and the Middle East they come – doctors, nurses and paramedics – to learn the craft of saving lives in the ‘golden hour’ after severe physical damage to a human body from external forces.

Endotracheal intubation, decompression of tension pneumothoraces and cricothyroidotomies were all on the menu. I couldn’t get enough of them. Many of the lectures and workshops practised skills beyond my previous level of training, skills I assumed to be out of my scope. Yet here I was, mixing it up with the best trauma surgeons in the world. I may have been transfixed by the experts, their stories and their tricks, yet had I known what the weekend would dish up on the streets of the capital, I would’ve been even more attentive.

After exiting The Leopard’s responder I can barely stand up. My eyes sting from the acrid stench of his smoking brakes.

In the middle of the road, on a hill out of Berea, a man lies on his back gazing up at the starless night. Superstitious Good Samaritans have removed the victim’s dirty takkies, placing the running shoes neatly beside his body, allowing a route of departure for his soul. Spreading from a single point on the man’s parietal skull, a stream of bright red blood shimmers in our headlights, still flowing freely, finding new tributaries in the bitumen, branching out and joining up, coursing to an open drain.

The Leopard lights a cigarette and leans against the car.

I glance at him, then down at the man, then back again. ‘Well?’

‘Well, what?’

‘He’s breathing.’

‘So? It’s agonal. You wanna tube him? Here,’ says The Leopard, casually opening the boot of the responder, retrieving his kit, passing it to me with his cigarette between his teeth, standing back again, entirely disinterested. Now that’s burnout, I think to myself. Typical burnout. Speeding to the scene, then doing nothing.

‘You won’t do it?’ I ask.

‘He’s chickenfeed, mate, all yours. Remember, don’t pivot on the teeth. If there’s blood in the airway, if you can’t see the cords, forget about it. We’re not going to stuff-up our suction this early in the shift.’

The vocal cords are Roman columns in the guy’s throat and I sink the tube easier than expected. Once connected to a bag, I breathe him up. The Leopard steps on his cigarette. He slinks over swinging his stethoscope casually, pops it in his ears and listens over each side of the chest and once over the stomach. Without saying a word he nods his approval. From the leather pouch at his waist he whips out a pen torch, flicks it over the wounded man’s eyes. The pupils are fixed on a middle distance, dilated to the edges, black as crude oil.

The Leopard chuckles.

‘Fok my, do all you people come here for learning miracles? Makes me lag, eh.’

He points to my knees either side of the patient’s head.

‘By the way, you’re kneeling in the brains.’

Early that morning I’d done a shift at Baragwaneth Hospital on the edge of Johannesburg’s sprawling Soweto townships. With three thousand beds it is one of the largest hospitals in the world and treats more than two thousand patients a day. Half of these are thought to be HIV positive. A constant stream of ambulances unloaded their sorry cargo onto rickety steel beds lined up side by side until, by mid-afternoon, there was barely room for any more. Teamed up with Simon, an Australian doctor with whom I’d participated in the ATLS, we cannulated, medicated and sutured non-stop.

While joining a doctor’s round in one of the wards, a boy of about sixteen was lying on a bed and as we passed by, he grabbed my wrist, pulling me close. His eyes pleaded as tears welled up and spilled onto his cheeks.

‘Please, friend, take it out, please take it out.’

On his right chest I could see a small bulge, the shape of a bullet sitting just beneath the epidermis. Exit wounds are not always a given, I’d learnt.

‘What’s your name?’

‘Treasure.’

‘What happened to you?’

‘Some men tried robbing me in Mofolo, I told them I had nothing to give but they klapped me hard and after I ran they shot.’

‘Bastards. Did it enter your back?’

‘Ja, bullet hit my spine, they told me it is shattered, they told me I am never walking again. When I fell down on the street I knew that. What will happen to me now? Last year my parents died in a minibus crash. There is no one to care for me.’

Already the doctors were three patients ahead – a ward round at Bara doesn’t wait. Treasure squeezed my arm tighter, sensing my urge to move on.

‘Please, brother, don’t go, please, take it out.’

‘Mate, I’m sorry for what happened to you, I really am. But the bullet is not interfering with any body function now, the damage is done. Maybe it will push out on its own one day.’

When I heard myself saying this to him – lying there unable to get up and walk to the open window, no father at the foot of his bed, no mother who named him her treasure holding his hand, no friends to help him pass the hours, the time he would forever spend turning over the memory of that one moment – I was filled with pity.

‘Just want this evil thing out,’ he said.

‘One minute,’ I told him. ‘I’ll bring a surgical kit.’

As I incised over the bullet, removing it with tweezers and dropping it into a steel kidney dish with a clink, I could feel Treasure’s muscles relaxing under the drape. A deep sigh passed his lips and his face smoothed out with relief.

‘God bless you, God bless you, God bless you,’ he whispered with his eyes closed, as if I had just exorcised an evil spirit. ‘God bless you forever.’

Among the pumps of a service station The Leopard unzips his bumbag. After looking around to make sure we are alone, he pulls out a 9mm semi-automatic handgun and slides out the magazine to show me its full load of rounds.

‘Got another one strapped to my ankle,’ he says.

With a sporadically effective police force, it is not unusual for paramedics to find themselves caught up in gunfights. Triage, the concept of sorting patients in multi-victim situations starting with the most critical, is superseded here by sheer self-preservation. If a member of one gang requests a paramedic to treat their own before those of an opposing group, it’s usually at gunpoint. The Leopard takes no chances.

‘Last year two of my colleagues were held up. Actually, it was an ambulance-jacking, they were left stranded in a bad place.’

As he drives me through Hillbrow, Johannesburg’s most densely populated urban slum of decrepit high-rise buildings, I see a neighbourhood I wouldn’t want to be stranded in either. Shopkeepers sit nervously behind thick iron bars and the blinking neon of pool halls and strip joints flickers on the figures of haggling prostitutes outside, their bodies shimmering with sweat.

‘Some of us call it Hellbrow. New Year’s Eve is the worst. People take pot shots with their guns from balconies, they let off fireworks horizontally, they throw furniture and other projectiles from windows, trying to hit people below. Few years back a fridge landed on a Metro ambulance. You never know what will come at you.’

Even ordinary party nights can be lethal in Jo’burg. Saturday evenings are difficult in most Western cities but here it’s a war-zone. Streets are jammed with people overflowing into the path of our car and the expectation of impending violence is palpable all around us. The Leopard locks the doors of the responder, says we’ll avoid the worst parts of the suburb, places even he won’t go unless accompanied by a police flying squad. He ignores red lights too, without being on a call. ‘You’ve got to keep moving. Robots will kill you in Johannesburg,’ he says, referring to the traffic signals. Rarely do I entertain irrational fears, but all heads seem turned on us tonight, eyes following the Audi as we pass, shady characters ready to pounce. In reality they could be just as well hoping we’ll stop and join them for a drink, take a break, have a laugh. But as we draw level with the next pub where words stencilled by the door read ‘No Guns Permitted’, I’m not so sure.

‘Zero Zero Three, come in.’

‘Three, go ahead.’

‘Man off a bridge, Yeoville.’

‘Rrrroger.’

Tossing individuals off bridges and towering apartment buildings is a preferred method of murder for some gangs in Jo’burg. Without witnesses and no weapon or identifying wounds, these deaths can be easily mistaken for suicide.

As The Leopard does a U-turn he points to the tallest building in Hillbrow, the notorious Ponte City Apartment block. This cylindrical skyscraper with a hollow core was built in 1975 as a luxury condo fifty-four storeys high. After the end of apartheid many gangs moved in and the penthouse suite on the top floor became the headquarters of a powerful Nigerian drug lord.

‘Once, we got half-a-dozen bodies in a week at the foot of that one,’ he says, flicking on the siren. But this was 2003 and things were changing. Using the South African Army as back-up, developers were evicting undesirables. Whether Ponte City’s former glory can be restored remains to be seen. Selling luxury apartments in the heart of a suburb where visiting the corner store for a carton of milk can get you killed will be tricky.

Half a minute down the road in Yeoville the traffic is backed up and we use the breakdown lane, our red and blue lights bouncing off the vehicles we pass. Under a freeway overpass we pull up behind a police van and see the officer in lane two standing over a young man lying face down, illuminated by the headlights of a late model Mercedes.

‘Lucky he missed the poor lady’s car, nice Merc that one,’ jokes the policeman. A woman in the front seat dabs her cheeks with a tissue.

I look up. The overpass is a good 20 or 25 metres high. No wonder the patient is groaning in agony. I’m surprised he’s even conscious.

Behind me The Leopard approaches with our gear. Seems the case has inspired him to show me what he’s made of. Or maybe the siren of our back-up ambulance wailing towards us has compelled him to act.

The policeman helps by manually stabilising the patient’s head. Calmly the Leopard scissors off the man’s shorts and T-shirt to expose him for a better examination. He slips a wide-bore IV into the cubital fossa without blinking and throws me a bag of Hartmann’s solution.

‘Five minutes on scene or we get docked,’ scoffs The Leopard. ‘Patient’s got an open-book pelvis with jelly legs, but it’s all about those five bloody minutes.’ He shakes his head and I know what he means. Time to hospital is the essence in trauma, but proper immobilisation, effective analgesia, cautious extrication and transport strategies will all, in the long run, reduce morbidity. Only by working the road can one truly appreciate ‘time’ as but one factor among many upon which an ambulance service should be judged.

Once the line is clear of air I connect and open it for a bolus. The Leopard double-checks the blood pressure, palpating seventy systolic. Falls from great heights often cause serious pelvic fractures like this, lacerating vessels internally and resulting in massive blood loss filling body cavities. This, in turn, can lead to absolute hypovolaemia – a condition of low blood volume – that could prove fatal.

‘Keep the fluids going wide open, we’ll shut it off at ninety systolic. Don’t go over ninety, got it?’

I nod.

Three paramedics from a Basic Life Support (BLS) ambulance arrive. They too comment on how lucky it is the Mercedes escaped damage. Two of them help with patient care, while the third, a stern-looking African man with spectacles on the end of his nose and epaulettes studded with shiny stars, stands to one side and starts a stopwatch hanging round his neck.

The Leopard looks over at me and rolls his eyes. ‘What did I tell you? Five minutes, let’s go!’ Maybe The Leopard is burnt out but tonight he’s playing the game. We’re being timed like athletes, timed by a stoney-faced supervisor with a digital stopwatch. Crazy.

Medics from the ambulance drag over a flat spine-board onto which we lay some pelvic sheeting. Once the patient is rolled over, we use this to stabilise him from the waist down, wrapped and clamped. Any unnecessary movement in pelvic fractures, even multiple examinations springing the iliac crests, increases internal bleeding and risk of death.

‘One, two, three, lift!’ The stretcher legs lock down and the trolley is wheeled to the ambulance. As the supervisor gets in the front seat he glances over at us and laughs.

‘Hey Rucker, four minutes, thirty-three. Close shave!’

The Leopard grunts and lights a cigarette.

From Netcare’s depot at Milpark we watch a retrieval helicopter descend onto a landing pad at the doorstep of the company’s very own fully equipped trauma hospital.

‘Heard it on the radio,’ The Leopard tells me. ‘Some lion safari gone wrong, a 4x4 rollover.’

Running parallel to public medical services, Netcare has fifty-three private hospitals like this throughout South Africa and Swaziland. Milpark alone employs some of the country’s brightest doctors, offering every imaginable specialty and a staggering ninety intensive care beds. For those who can afford private health cover the company has become South Africa’s provider of choice. But as an act of goodwill to the poorer people of South Africa, Netcare offers its ambulance services free to those who earn below a certain income threshold. Nowadays, the vast majority of emergency calls are made by non-subscribers. These patients are, however, always conveyed to public hospitals. Although it is currently common practice in South Africa to dial 911 – Netcare’s clever exploitation of the widely known US emergency number – bystanders will also ring the government’s metro ambulance service at the same time. In a crisis people will take whatever ambulance comes first.

As a consequence, driving to emergencies has become a frantic race between the public and private services. This ‘healthy competition’ has only improved response times in Johannesburg, according to Netcare medics. Relationships between crews from both systems generally remain harmonious despite this challenge. Stress comes instead from pressure placed on them by management to reach the scene first in order to uphold the service’s image as the quickest.

While good for the public, it’s a dangerous game for medics. In 2002, nineteen ambulances were written-off in the city of Johannesburg, mostly by Metro Ambulance Service drivers. Netcare are not so worried. Official figures show their average response times are five minutes faster than the government service.

‘Sometimes on the way to hospital with the patient we pass the Metro ambulance still heading to the scene,’ chuckles The Leopard. ‘We always give a little wave, of course.’

As we prowl for work in those raw, bloodstained streets of central Johannesburg, I have become The Leopard’s cub, learning to hunt with the master.

‘Are you ever afraid?’ I ask him. Stories of gun battles with drug gangs, resuscitations at knifepoint and snipers taking shots at reflective vests have kept me on the edge of my seat all night.

‘Ja, sure I get afraid.’

‘Of what?’

‘HIV.’

It isn’t what I expected him to say.

‘Average sixty people are shot every day here, ten thousand people die on the roads each year, 90 per cent of our calls are trauma, but HIV is the leading cause of death. At least 20 per cent of sub-Saharan Africa is HIV positive. Just do the math. If you consider 90 per cent of our work is trauma with active bleeding and 20 per cent of these patients are HIV positive, you will understand what we’re really afraid of. Get blood on you in Australia, England, America and you don’t sweat much. Get blood on you here and you don’t sleep till the results come back.’

The Leopard plans to enrol in a paramedic research degree, a doctorate perhaps. ‘I need to get off the road. I have children now, they live with my wife but I want to see more of them. You know, I have a responsibility to them, a responsibility to stay alive.’

The streets of Johannesburg seem eons away from the immense beauty of South Africa’s wilderness. The contrast is extreme. But then, some of the most stunning places in the world have a dark underbelly, a place shared by the poor, the sad, the criminal, the beggar, the victim and the paramedic.

‘Zero zero three?’

Reluctantly The Leopard picks up the handset and replies. Our lights and siren ignite the dark road ahead.

‘It’s not a bad neighbourhood, this,’ says The Leopard. ‘We’re less than a kilometre from Hillbrow, I have a drink here sometimes, you know, during the daytime.’

But descending a steep hill we are first on the scene of a chaos like none I’ve encountered.

From what I can make out, a fully laden semitrailer lost control, veered to the opposite side of the road, crushed five cars and continued on to plough through a restaurant packed with diners, finally coming to rest deep within the building.

The carnage is widespread and horrific.

Bodies lie everywhere. Cries and screams and groans puncture the air. Hands pull us this way and that. I’m dizzy and cannot focus on any one patient, there are so many, perhaps twenty, perhaps more. Where do we start? Triage, triage. My French comes back to me. We need to sort them, make sense of it, get perspective.

The Leopard is so cool it shames me. He strides through the devastation like a war-hardened general, calmly slipping his hands into latex gloves. He takes no gear, no oxygen kit, no medicine, no bandages. Just the man and his portable radio. One at a time he stoops down to check the breathing and circulation of those lying motionless. Effortlessly he elicits responses from those who are conscious and checks the smashed vehicles and the truck for occupants. As I follow behind him, I finally hear him speak into his handset, his voice steady and commanding, his report plain and precise.

‘MVA, truck versus restaurant, no persons trapped, four dead, sixteen patients on the ground, unknown number of walking wounded, need fire brigade and as many ambulances you’ve got handy.’

The Leopard grabs my shoulder and points to a man lying near a car that looks like it’s been through a wrecking yard. ‘Start with that guy, he’s not well. I’m going to delegate the back-up as it comes.’

From the responder I get our gear and race back, stepping over the bodies of those beyond help.

‘He can’t feel his legs,’ cries the man’s wife, crouching beside him. ‘He can’t feel them!’

I ask her name. It’s Melanie. She tells me the patient is Martin. Today is their wedding anniversary and he took her for dinner, alfresco, with candles.

‘Listen,’ I grab her attention. ‘Melanie, you’ve got to help me now. Here, take Martin’s head and don’t let it move. Keep talking to him. Stay calm because you need to keep him calm. We’ve got a job to do and we’ll do the job together.’

After fitting the oxygen mask, I mould a hard collar round Martin’s neck and begin a head-to-toe examination. His breathing is rapid and shallow. I place my stethoscope in his armpits and listen. Limited air entry on the right, I’m certain of it. There is movement and crepitus, a popping sound and grating of crushed ribs when I palpate the chest wall. I suspect a collapsed lung. It may be tensioning, in which case an immediate procedure to release the pressure with a needle is required. As I break out in a sweat at the prospect of doing this, a Netcare ambulance team with a senior paramedic join me and begin cannulating and getting ready to board the patient. They will decompress the man’s chest once loaded up, the medic tells me. They work at lightning speed and I wonder if another supervisor is standing somewhere in the shadows holding a stopwatch.

Medics are swarming all over the site now. Metro EMS, Netcare 911, even ER24, a company I’ve not yet come across. Suddenly The Leopard is behind me, leaning in.

‘Boet,’ he says in Afrikaans, meaning ‘brother’. ‘We got to go, we got a gunshot to the head just round the corner, they got no one for it.’

I’m stunned. Broken glass crunches and mixes with blood underfoot as I carry the responder kit back to the car. It’s an awkward response in tragic times, but as I get into the front seat I begin to laugh. I laugh at the sheer absurdity of leaving the biggest accident of my career to attend a shooting. I laugh because it has taken me less than twenty-four hours to reach this point, this point where a paramedic’s work in Johannesburg is encapsulated entirely by a single, staggering moment of madness.

And the night is but young.

SHEIK, RATTLE AND ROLL

England

On the rain-drenched morning Henry takes the wheel I am secretly relieved the old man we are carting from one sad nursing home to another is afflicted by a state of dementia so advanced he is seemingly oblivious to our existence and stares silently ahead into a land beyond. Normally I wouldn’t wish the illness on my worst enemy. But as Henry pushes the siren and races down Herne Hill towards Brixton at the speed of a Grand Prix driver on amphetamines, it’s a good thing our patient – someone’s dear grandpa – is numb to it all. The old man bounces around like a leg of ham in a delivery van. In fact, groceries and daily mail probably get better rides than this in London.

Approaching the intersection of Milkwood Road and Half Moon Lane is where we have the fourth near miss of the day. A car appears from nowhere, as Henry puts it afterwards, making it sound like a supernatural phenomenon beyond human comprehension. While hurtling through the red signal without slowing I assume this apparition has approached from the right, but I see nothing at all as I’m riding in the back clutching a crossbar with one hand and the patient’s shoulder with the other. When Henry plants his generous weight on the brakes I’m only half ready for it. Equipment flies into the front cabin, some of it catching me while passing. Airborne oxygen masks and kidney dishes are the least of my concerns. Our old man, drooling and wide-eyed, has long lost the instinct to hold onto the stretcher rails and our extreme deceleration threatens to catapult him through the windscreen. I have little choice but to throw myself on top of the patient, his brittle bones digging into me as I pin him to the mattress with my body. A sound of screeching tyres and angry horns is followed by the choking smoke of burning rubber pumping into the back of the wagon.

‘You all right, geezer?’ Henry asks once he has pulled over past the intersection, his face pale and puffing.

‘Think so,’ I say in a neutral tone, until it occurs to me how pissed-off I really am and I add, ‘Why the urgency anyway, mate? We’re going to a bloody nursing home.’

‘He should ’ave seen me comin’, tha bastard.’

But Henry has only himself to blame and he knows it. Lights and sirens are merely a request for people to give way, not a demand.

Henry’s hands are trembling as he collects the bits and pieces littering the front cabin. Though he seems shaken, I know he will do it again, maybe even today. Like a poker machine that eventually pays out, we’re long overdue for a prang. And if eventually he kills a man, or more than one, I want nothing to do with it.

Got to quit, got to quit, got to quit.

What am I still doing here?

With its prestigious-sounding name no one would suspect a shoddy operation from this private Harley Street ambulance service. Ambulances plush as limousines, I thought. Only these would satisfy the British high society and foreign millionaires who visit the nation’s famous strip of specialist rooms and luxury clinics.

Perhaps the greatest insult one can give a genuine paramedic is to call him or her an ambulance driver, yet this is what I was, my paramedic degree as useful as a sheet of toilet paper. The art of driving grannies to doctors’ appointments had, as I recall, never been covered. Why my skills were unattractive to the London Ambulance Service (LAS) when I applied for recognition of prior learning, I just don’t know. The LAS was naturally my first choice, but the process facing foreign paramedics hoping to get on London’s ambulances is known to be so long and painful that most don’t bother. Ironically, ambulance services in sunnier countries of the world like Australia and New Zealand have made quite a business of poaching British paramedics and have done this so aggressively over the past decade it has created a shortage of paramedics in England, and a minor political storm.

Wasted skills aside, better money can be made working for private patient transport services anyway, even if it represents a significant drop in action. Nor is it wise to remain jobless while waiting for the bureaucratic process of the National Health Service. As Iraqi doctors and Iranian surgeons flipping burgers in London’s takeaway joints can attest, survival rules over pride in this cruellest of cities. Yes, we’d all like to work in our chosen careers, but decent heating and square meals are the only way to get through winter, and Kass, my then girlfriend now wife, needs a new woollen coat. Still, I wish we had chosen Barcelona over London when deciding on a city in which to base ourselves for a few years of European exploration.

It’s colder than deep-sea diving off Alaska. Even with the windows up and my green fleece zipped tight I feel like an ice sculpture. We drop the patient off at his five-star nursing home – quite literally ‘drop’ as Henry claims he ‘wasn’t ready’ with the head end of the stretcher at the moment I called ‘one, two, three’. I’ve come to expect this kind of thing when Henry is way past his fried chicken and chips time. It will be his third lot in a single morning. Another of his shirt buttons is sure to pop before the day’s end.

We park at a Harley Street corner so we can make a rapid response to the next boring transfer. As the rain thunders on the window, I watch Henry munching fried chicken, getting it tangled in his scraggly ginger beard and dropping it down the front of his uniform. In fact, his uniform is already stained from previous fried chickens. With a belly like that there’s only one place falling chicken tends to land.

‘So, you is telling me you once got a hundred quid tip off a Arab?’ he says as he eats, displaying the contents of his mouth.

‘Yeah, Kuwaiti royal family.’

‘Kuwai-i royal family?’ he licks his lips, looks annoyed. ‘I neva got nufink offa tha Kuwai-i royal family. Took one of ’em in too, I did. Had a hip done, he did. But tha Kuwai-i royal family never looked arfta Henry, did vey.’

I sigh and glance at my watch, wondering what the Kuwaiti royal family would have thought about an ambulance stinking of fried chicken, driven by a maniac.

‘Mate, you know we got a Arab later on,’ says Henry, ‘four-firtey in from Heafrow …’

‘An Arab, Henry, it’s an Arab.’

‘Yeah, dats wot I said, a Arab.’

Worst thing about having an ambulance with a broken stereo is that it forces one to listen to a partner chewing fried chicken and using bad English in England.

‘Well,’ I reply, ‘it’s nearly two o’clock, and you know the traffic.’

Henry knows the traffic all right. This is part of the problem. He loves nothing more than to plan his day so that unless we use our lights and sirens we’ll be late to every appointment and pick-up. This is because, quite frankly, he loves to use the lights and sirens. When I first met Henry I spotted him right away as a wannabe paramedic who never made the grade. Being an ambulance driver is a little boy’s fantasy as much as being a train driver or bus driver. In most emergency medical systems, however, ambulance drivers must also use clinical skills normally reserved for doctors. This naturally excludes a good number of candidates, Henry included. Society is full of disappointed men and women who have longed to drive ambulances from the age of five when they spent each day constructing matchbox car crashes and sending matchbox ambulances to the scene. Recruitment departments of public emergency services are perpetually inundated by such applicants and spend half their time palming them off.

The only other qualified paramedic working at the company was fired from the London Ambulance Service for visiting a Kensington barbershop while on duty. When I heard this I told him it sounded like unfair dismissal. Medics are normally permitted to visit coffee houses and corner stores in their catchments so long as they can quickly respond. Why not a barbershop? I mean, how long does it take to throw off an apron, brush down a uniform and go out with half a cut? Not long at all. If anything, the gentleman’s commitment to looking sharp and tidy in the workplace should have been commended. As much as I’d prefer it I’m never assigned to work with him. Our boss wants one qualified medic per wagon. And apart from the two of us, the rest are a bunch of fantasists who recently discovered a community college somewhere outside London conducting a five-day first-aid course they believe allows them to use the title ‘paramedic’. Never mind it took me four years of study to earn the same. While I don’t bother wearing anything at all to identify myself as one, these men could not be more decorated. From emergency service catalogues they have mail-ordered paramedic insignia of every description. Cloth patches, embroidered epaulettes, shiny badges, clip-on pins, reflective vests and so on, all emblazoned with the word ‘paramedic’; one ambulance driver is so covered in pins and badges he looks like a walking Christmas tree.

Then there is the gear. While I have trouble locating my stethoscope most days, these men have got every imaginable utility dangling from their belts. There are Leatherman knives, wallets for gloves and scissors, phone holders, torches of various sizes, rolls of Leucoplast, radio holsters, mini disinfectant dispensers, rubber tourniquets and various other oddly-shaped black pouches containing everything but handcuffs. All these are attached for the prime purpose of looking as much like a paramedic as possible, or at least how they imagine a paramedic must look. This I find most entertaining and wonder how I’ve managed to do the same job for so long with nothing on my belt but a buckle.

While some veteran medics would be irritated by such things, I am way more frustrated by the widespread and reckless use of emergency warning devices.

Prince Abdullah al-Sabah’s private jet is to land at Heathrow in twenty minutes and, as I remember from my last conversation with an al-Sabah, they are not fond of tardiness. The Sabahs are thought to hold the largest number of shares in almost all blue-chip companies in the Western world and to have a combined family wealth of US$200 billion. On first meeting the Kuwaitis, my politeness to a veiled female family member was generously rewarded with a crisp fifty pound note pulled from a wad of cash thick as a brick and dispensed by a keffiyeh-wearing aide. Accepting money from patients beyond the agreed payment for services is considered unethical in the medical profession and strictly forbidden for government ambulance workers and hospital staff. But in London’s private health care, tipping seems somehow acceptable and is not uncommon.

‘White car on the left!’ I warn Henry as he comes dangerously close to clipping a sedan that has failed to pull over far enough.

My head is throbbing with the beat of the siren. The Ford Transit parts traffic out of the city like Moses did the Red Sea. It’s slow going, but we’re getting through faster than anyone else.

What is the public thinking, I wonder, those distressed commuters struggling to edge out of our way, imagining the worst? What if they knew that Henry was using his lights and sirens because he thinks it’s fun, because he intentionally ate his fried chicken slow enough for the traffic to build up? And what if they knew I was letting him do it because I’d hate to be late for the Kuwaiti royal family, because I’m hoping for another tip, more than last time – if I’m lucky.

Back in Sydney severe consequences result from the inappropriate use of lights and sirens. Not that we’d bother, anyway. We’re so busy most of the time it’s a relief when the siren is off, allowing us a little peace and quiet. Warning devices are only a novelty for those who don’t use them much.

‘Ow of tha way! Comin’ fru! Move it! Move it! Move it!’ shouts Henry.

‘They can’t hear you,’ I say, wishing he’d shut up.

‘All right, but vey can see me, can’t vey.’

‘See you what?’

‘See me yellin’. Yellin’ and gesticalatin’!’

I don’t know how many private ambulance services there are in London, but ever since routine patient transport was outsourced, every little boy rejected from the LAS could finally drive an ambulance as fast as they like with ‘blues and twos’ – blue flashing lights and a two-tone siren. It was absurd and out of control. By my second day at this company I’d survived three near-death experiences and one flying patient. But when I raised the matter with the boss – a middle-aged, chain-smoking, sarcastic woman with the face of an East London gangster – she looked me square in the eye and croaked, ‘You know by now what the traffic in London is like, son, don’t you?’

And I replied, ‘Yes, but it’s dangerous going fast without a pressing reason.’

And she said, ‘Harley Street patients are special, you understand. They expect the best. They have never waited for anything in their lives. They don’t expect to lie in ambulances while our drivers inch along in traffic, do they now?’

But a day later she inadvertently revealed her true reason for ignoring the fun crews were having with lights and sirens when Henry called up and told her we were unlikely to complete two jobs in the designated time frame.

‘Well,’ she said via the crackly radio, ‘what have you got those pretty lights on your wagon for, Henry?’

Turnover. It is all about turnover and profit. The faster we do a job, the quicker we’re on to the next. We make deliveries like any courier company, but because we deliver human cargo we can make our deliveries in half the time by halting on-coming traffic and momentarily paralysing city intersections.

Henry brakes heavily. ‘Wanka!’ he shouts.‘Got evry fink on, idiot!’

And with everything on we skid into Heathrow making such a racket that for a second airport security must think some hijacking has taken place without their knowledge.

But no, all this Arab wants is a quality heart bypass.

We meet the patient sunk into a deep leather recliner in the lavish corporate jet building, a man in his sixties wearing a stiff white dishdasha and rockstar sunglasses. He’s very pleased when I greet him with the traditional Assalam Aleikum but looks with a little disgust at Henry who struggles to negotiate a leather ottoman with the stretcher.

‘How was your flight?’ I ask the sheik.

‘Bekhair,’ he says, and his aide appears, a different one from last time, and translates.

‘Fine, he says flight is fine, thank you,’ says the aide.

Henry is by my side now. I can smell him.

‘Good to go ven?’ he asks, looking at the aide expectantly. But no wad of cash appears and we stand in awkward silence, a silence like the one after hotel porters take your bags up and you don’t have any change to tip them with. Why Henry expects the sheik will slip him some cash before he’s been driven anywhere is beyond me.

After half a minute, Henry readies the stretcher and we help the sheik climb on.

It’s a rough ride back to Harley Street. I’ve strapped the sheik down well but notice the skin over his knuckles blanche while gripping the stretcher rails. The sheik says something loudly to his aide, raising his voice over Henry’s siren. I fear that any chance of getting a tip now is out of the question. But I’m wrong. Instead of lodging his complaint about the journey, the sheik’s aide leans over and thrusts a fifty pound note into my palm.

‘No, no, I’m not supposed to take this,’ I protest.

But Henry’s siren is so loud I can’t really hear myself and when I try to hand the money back the sheik’s aide takes it and forcefully stuffs it into my top pocket. There is a certain desperation in the way he has given me the tip that makes me think for a moment I’m being bribed to take the wheel and slow things down. When Henry veers sharply to avoid something and leans on the horn for thirty seconds, cursing grotesquely, I consider it. In Kuwait, my partner would be promptly executed for driving like this with an al-Sabah on board. ‘Allah, Allah, Allah!’ cries the sheik.

Really got to quit, I think. The fifty pounds in my top pocket will hardly tide me over until the next job. But I don’t care.

After dropping off the sheik at a cardiologist, Henry curses the Kuwaiti royal family for not helping us out and how the House of Saud is far more generous.

I shrug, choosing not to mention my tip.

‘Henry,’ I say politely as we reach the Baker Street tube station, ‘you don’t mind dropping me off here, do you?’

‘Right ’ere?’ he asks, raising his eyebrows.

‘Yes please. And do me another favour, will you?’

‘What’s tha’?’

‘Tell the boss I’ve resigned.’

ALL QUIET! NEWS BULLETIN!

The Philippines

Lumbering like the giant propellers of an ocean liner, the fan blades turn too slowly and too high above us to cool the night. But the loose chugging and whooshing is sending me to sleep. Behind a heavy wooden desk illuminated by a strip of neon screwed into one of the peppermint-green walls is the chief of the Philippine General Hospital’s Emergency Medical Service, Manolo Pe-Yan, a plump man, unusually serious for a Filipino. Seriousness, however, does not always translate to professional appearance and Manolo is wearing the same singlet he’s been wearing for a week, stained by a dark bib of sweat, his head tipping forward then up again as he sleeps.

It’s 1 am on a Saturday morning. Two white uniform shirts are hanging on the posts of a single steel bed beside me. Snoring soundly upon it, curled up together despite the heat, is a crew of emergency medical technicians (EMTs) seemingly content with the status quo – a parked ambulance and no calls on a night when all manner of accidents and murders are occurring in the action-packed metropolis. A stone’s throw from where these medics are sleeping there is a constant stream of jeepneys, taxis and tricycles screeching to a halt outside the hospital emergency department. Onto the doorstep their contents are dumped: an assortment of stabbed and mauled victims; unconscious men with occluded airways, bodies made limp by the fractures of long falls and pedestrians with broken necks. Last week I worked a few shifts in the emergency department and dragged these people in, seeing how nasty and critical injuries and medical cases become without pre-hospital care. And while I did this, across an island of lawn and flowerbeds, under a low tin awning, two beautiful late-model Chevrolet ambulances stood washed and polished – and silent.

‘Okay, tayo marinig ng ibang song!’ Another Filipino hit is announced on a little transistor radio. It’s all we listen to. A World War II ceiling fan and cheesy music, neither of which is ever switched off – the ceiling fan for obvious reasons and the radio because, in its truest definition relating to ambulance work, we are listening out for jobs. There is still no central emergency number in The Philippines, no control room or ambulance dispatch. So we wait, as we do most days and nights, monitoring the half-hour news bulletins on ordinary FM radio and the occasional updates between Pinoy rock classics by Sugar Hiccup and Tropical Depression. Occasionally, maybe once a week, a member of the public will arrive breathless at the ambulance station, pointing in the general direction of some traffic collision nearby. But mostly we wait for a radio announcement – sometimes for weeks on end – about a pile-up on one of the many highways and skyways crossing Manila. Last month, both ambulance crews took it upon themselves to respond to a train derailment after hearing a report on the radio, but have since done little else.

The air is thick with humidity and the smell of green mangoes. I look around the room and see I’m the last one awake. Having no comprehension of Tagalog, the 1 am news means nothing to me. Half of Manila may have gone up in flames and I wouldn’t know. Nor would my colleagues stir from their slumber. There is nothing to do but stretch out on a bench near the door and submit to the urge to close my eyes.

In heat like this my dreams are always bizarre. The emperor of a mighty country, suddenly inspired into a random act of generosity, orders all hungry tramps in the land to be issued a jar of his finest caviar. But one of the tramps is unhappy and says, ‘Just give me a damn sandwich!’ The tramp says this about the same time I wake up and turn over. While I drift off to sleep again I comprehend the dream may well have been about our two ambulances donated by the United States government. They came with the latest, high-tech equipment, with pulse oximetry, twelve-lead ECG machines and pneumatic ventilators. Like caviar to a tramp are these ambulances to The Philippines’ largest public hospital. Only yesterday we took a patient in from another facility hooked up to our automatic ventilator and found there were no ventilators in the intensive care unit of the hospital. How odd it was to see our state-of-the-art device replaced by a simple bag-valve-mask – a bag manually squeezed every four seconds or so by the patient’s beloved without interruption, sometimes for months. No wonder the bag-valve-mask is known here as as a ‘relative ventilator’. And because the chain of health care is only as strong as its weakest link, there was considerable discussion among the EMTs about why they bothered connecting the ventilator in the first place. More interesting to me was to volunteer in a country where ambulances are better equipped than the hospitals they deliver to. It’s May 1998 and I’m only here for six weeks – half my time ambulance-riding, half island-hopping – far too short a period to help create awareness of a paramedical service among twenty million people in the most densely populated city in the world.

Manolo nudges me with a Philippine breakfast plate of champorado – a combination of sticky chocolate rice served with salty fish, a fish which I detest and usually discreetly dispose of so as not to offend my hosts.

‘We have very important meeting in the evening, Joe,’ grunts Manolo, using the rather annoying nickname I share with every other Western male who bears the slightest resemblance to an American GI. Manolo’s face doesn’t give anything away, even when I know he’s being funny. I’m certain it’s his own type of humour, that he’s one of those straight-faced funny men.

I raise my eyebrows and take the bowl.

‘Chinese Fire Brigade again?’ I ask.

‘You’ll see, Joe,’ he answers.

The two EMTs, Juan and Fermin, are awake. Fermin is brushing his teeth in a sink by the door while Juan runs a comb through his hair over and over again, staring ahead with a drowsy gaze. Neither of them bothers getting into their uniform shirts. They only do this if a job comes in or while escorting me across town to the headquarters of the Chinese Fire Brigade where I lecture in first aid. Three nights ago they also turned out nicely for a dinner with the fire chief whose selection of deep-fried insects and marinated grubs revolved on the centre of the table like a carousel of horrors. With this grisly platter still in mind, I hope this evening’s meeting will be nowhere near Chinatown.

Manolo snaps at Fermin to turn off the tap.

‘All quiet! News bulletin!’ he barks.