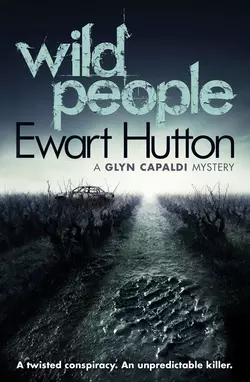

Wild People

Ewart Hutton

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 191.96 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 28.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A DS Glyn Capaldi MysteryDS Glyn Capaldi is in hospital recuperating from concussion and the after-effects of a car crash.But, worse than that, a young woman is dead. She was the passenger in the car, whom he was bringing in for questioning following a night operation in a remote rural location.Glyn is initially riven with guilt and self-recrimination. Until he starts to question the possibility that it may not have been an accident. But, if not, who had been the target? Had he made an enemy capable of achieving that level of planning and implementation? Or, if not him, what could a young woman have possibly done in her short country life to warrant that degree of retribution?Glyn, on sick leave, has time on his hands to explore the background to these questions, and, in doing so, confronts a conspiracy that envelops arson, torture, blackmail, and leaves a clutter of bodies that further muddy the already murky waters.