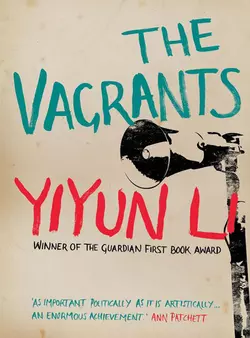

The Vagrants

Yiyun Li

The novel from the Guardian First Book Award-winning Chinese writer acclaimed by Michel Faber as having ‘the talent, the vision and the respect for life's insoluble mysteries to be a truly fine writer.’In the provincial town of Muddy Waters in China, a young woman named Gu Shan is sentenced to death for her loss of faith in Communism. She is twenty-eight years old and has already spent ten years in prison. The citizens stage a protest after her death and, over the following six weeks, the town goes through uncertainty, hope, and fear until eventually the rebellion is brutally suppressed.We follow the pain of Gu Shan's parents, the hope and fear of the leaders of the protest and their families. Even those who seem unconnected to the tragedy – an eleven-year-old boy seeking fame and glory, a nineteen-year-old village idiot in love with a young and deformed girl, and old couple making a living by scavenging the town's garbage cans – are caught up in remorseless turn of events.Yiyun Li's novel is based on the true story which took place in China in 1979.

YIYUN LI

The Vagrants

DEDICATION (#ulink_bb5c7f02-cabb-5855-ac4f-81ea77408a9a)

For my parents

CONTENTS

COVER (#u3dc86087-b17b-5783-8918-eeedd17974eb)

TITLE PAGE (#u21003bb3-122d-5bac-8cad-35a0cd54b034)

DEDICATION (#ud0a6e3ad-bcb0-581e-9467-394006f57674)

PART I (#u937448c7-b865-556d-82e0-b919e6c2a76a)

ONE (#u02784d69-d011-5e1b-828e-bbbacba1106f)

TWO (#u39cd5001-ccc8-53d4-9994-d245d5f2a1e0)

THREE (#uc1854e82-a43f-5586-9f39-d3bc9e15065e)

FOUR (#u4efca7e2-6240-527b-b759-1c46892ac4f2)

FIVE (#litres_trial_promo)

SIX (#litres_trial_promo)

PART II (#litres_trial_promo)

SEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

EIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

NINE (#litres_trial_promo)

PART III (#litres_trial_promo)

TEN (#litres_trial_promo)

ELEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

TWELVE (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

ALSO BY THE AUTHOR (#litres_trial_promo)

COPYRIGHT (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#litres_trial_promo)

Part I (#ulink_69caa7db-98f9-5471-83e3-3fd604704273)

ONE (#ulink_d53b0ab3-d00a-5590-bbf7-d539af8d2789)

The day started before sunrise, on March 21, 1979, when Teacher Gu woke up and found his wife sobbing quietly into her blanket. A day of equality it was, or so it had occurred to Teacher Gu many times when he had pondered the date, the spring equinox, and again the thought came to him: Their daughter’s life would end on this day, when neither the sun nor its shadow reigned. A day later the sun would come closer to her and to the others on this side of the world, imperceptible perhaps to dull human eyes at first, but birds and worms and trees and rivers would sense the change in the air, and they would make it their responsibility to manifest the changing of seasons. How many miles of river melting and how many trees of blossoms blooming would it take for the season to be called spring? But such naming must mean little to the rivers and flowers, when they repeat their rhythms with faithfulness and indifference. The date set for his daughter to die was as arbitrary as her crime, determined by the court, of being an unrepentant counterrevolutionary; only the unwise would look for significance in a random date. Teacher Gu willed his body to stay still and hoped his wife would soon realize that he was awake.

She continued to cry. After a moment, he got out of bed and turned on the only light in the bedroom, an aging 10-watt bulb. A red plastic clothesline ran from one end of the bedroom to the other; the laundry his wife had hung up the night before was damp and cold, and the clothesline sagged from the weight. The fire had died in the small stove in a corner of the room. Teacher Gu thought of adding coal to the stove himself, and then decided against it. His wife, on any other day, would be the one to revive the fire. He would leave the stove for her to tend.

From the clothesline he retrieved a handkerchief, white, with printed red Chinese characters—a slogan demanding absolute loyalty to the Communist Party from every citizen—and laid it on her pillow. “Everybody dies,” he said.

Mrs. Gu pressed the handkerchief to her eyes. Soon the wet stains expanded, turning the slogan crimson.

“Think of today as the day we pay everything off,” Teacher Gu said. “The whole debt.”

“What debt? What do we owe?” his wife demanded, and he winced at the unfamiliar shrillness in her voice. “What are we owed?”

He had no intention of arguing with her, nor had he answers to her questions. He quietly dressed and moved to the front room, leaving the bedroom door ajar.

The front room, which served as kitchen and dining room, as well as their daughter Shan’s bedroom before her arrest, was half the size of the bedroom and cluttered with decades of accumulations. A few jars, once used annually to make Shan’s favorite pickles, sat empty and dusty on top of one another in a corner. Next to the jars was a cardboard box in which Teacher Gu and Mrs. Gu kept their two hens, as much for companionship as for the few eggs they laid. Upon hearing Teacher Gu’s steps, the hens stirred, but he ignored them. He put on his old sheepskin coat, and before leaving the house, he tore a sheet bearing the date of the previous day off the calendar, a habit he had maintained for decades. Even in the unlit room, the date, March 21, 1979, and the small characters underneath, Spring Equinox, stood out. He tore the second sheet off too and squeezed the two thin squares of paper into a ball. He himself was breaking a ritual now, but there was no point in pretending that this was a day like any other.

Teacher Gu walked to the public outhouse at the end of the alley. On normal days his wife would trail behind him. They were a couple of habit, their morning routine unchanged for the past ten years. The alarm went off at six o’clock and they would get up at once. When they returned from the outhouse, they would take turns washing at the sink, she pumping the water out for both of them, neither speaking.

A few steps away from the house, Teacher Gu spotted a white sheet with a huge red check marked across it, pasted on the wall of the row houses, and he knew that it carried the message of his daughter’s death. Apart from the lone streetlamp at the far end of the alley and a few dim morning stars, it was dark. Teacher Gu walked closer, and saw that the characters in the announcement were written in the ancient Li-styled calligraphy, each stroke carrying extra weight, as if the writer had been used to such a task, spelling out someone’s imminent death with unhurried elegance. Teacher Gu imagined the name belonging to a stranger, whose sin was not of the mind, but a physical one. He could then, out of the habit of an intellectual, ignore the grimness of the crime—a rape, a murder, a robbery, or any misdeed against innocent souls—and appreciate the calligraphy for its aesthetic merit, but the name was none other than the one he had chosen for his daughter, Gu Shan.

Teacher Gu had long ago ceased to understand the person bearing that name. He and his wife had been timid, law-abiding citizens all their lives. Since the age of fourteen, Shan had been wild with passions he could not grasp, first a fanatic believer in Chairman Mao and his Cultural Revolution, and later an adamant nonbeliever and a harsh critic of her generation’s revolutionary zeal. In ancient tales she could have been one of those divine creatures who borrow their mothers’ wombs to enter the mortal world and make a name for themselves, as a heroine or a devil, depending on the intention of the heavenly powers. Teacher Gu and his wife could have been her parents for as long as she needed them to nurture her. But even in those old tales, the parents, bereft when their children left them for some destined calling, ended up heartbroken, flesh-and-blood humans as they were, unable to envision a life larger than their own.

Teacher Gu heard the creak of a gate down the alley, and he hurried to leave before he was caught weeping in front of the announcement. His daughter was a counterrevolutionary, and it was a perilous situation for anyone, her parents included, to be seen shedding tears over her looming death.

When Teacher Gu returned home, he found his wife rummaging in an old trunk. A few young girls’ outfits, the ones that she had been unwilling to sell to secondhand stores when Shan had outgrown them, were laid out on the unmade bed. Soon more were added to the pile, blouses and trousers, a few pairs of nylon socks, some belonging to Shan before her arrest but most of them her mother’s. “We haven’t bought her any new clothes for ten years,” his wife explained to him in a calm voice, folding a woolen Mao jacket and a pair of matching trousers that Mrs. Gu wore only for holidays and special occasions. “We’ll have to make do with mine.”

It was the custom of the region that when a child died, the parents burned her clothes and shoes to keep the child warm and comfortable on the trip to the next world. Teacher Gu had felt for the parents he’d seen burning bags at crossroads, calling out the names of their children, but he could not imagine his wife, or himself, doing this. At twenty-eight—twenty-eight, three months, and eleven days old, which she would always be from now on—Shan was no longer a child. Neither of them could go to a crossroad and call out to her counterrevolutionary ghost.

“I should have remembered to buy a new pair of dress shoes for her,” his wife said. She placed an old pair of Shan’s leather shoes next to her own sandals on top of the pile. “She loves leather shoes.”

Teacher Gu watched his wife pack the outfits and shoes into a cloth bag. He had always thought that the worst form of grieving was to treat the afterlife as a continuity of living—that people would carry on the burden of living not only for themselves but also for the dead. Be aware not to fall into the futile and childish tradition of uneducated villagers, he thought of reminding his wife, but when he opened his mouth, he could not find words gentle enough for his message. He left her abruptly for the front room.

The small cooking stove was still unlit. The two hens in the cardboard box clucked with hungry expectation. On a normal day his wife would start the fire and cook the leftover rice into porridge while he fed the hens a small handful of millet. Teacher Gu refilled the food tin. The hens looked as attentive in their eating as did his wife in her packing. He pushed a dustpan underneath the stove and noisily opened the ash grate. Yesterday’s ashes fell into the dustpan without a sound.

“Shall we send the clothes to her now?” his wife asked. She was standing by the door, a plump bag in her arms. “I’ll start the fire when we come back,” she said when he did not reply.

“We can’t go out and burn that bag,” Teacher Gu whispered.

His wife stared at him with a questioning look.

“It’s not the right thing to do,” he said. It frustrated him that he had to explain these things to her. “It’s superstitious, reactionary—it’s all wrong.”

“What is the right thing to do? To applaud the murderers of our daughter?” The unfamiliar shrillness had returned to her voice, and her face took on a harsh expression.

“Everybody dies,” he said.

“Shan is being murdered. She is innocent.”

“It’s not up to us to decide such things,” he said. For a second he almost blurted out that their daughter was not as innocent as his wife thought. It was not a surprise that a mother was the first one to forgive and forget her own child’s wrongdoing.

“I’m not talking about what we could decide,” she said, raising her voice. “I’m asking for your conscience. Do you really believe she should die because of what she has written?”

Conscience is not part of what one needs to live, Teacher Gu thought, but before he could say anything, someone knocked on the thin wall that separated their house from their neighbors’, a protest at the noise they were making at such an early hour perhaps, or, more probably, a warning. Their next-door neighbors were a young couple who had moved in a year earlier; the wife, a branch leader of the district Communist Youth League, had come to the Gus’ house twice and questioned them about their attitudes toward their imprisoned daughter. “The party and the people have put trusting hands on your shoulders, and it’s up to you to help her correct her mistake,” the woman had said both times, observing their reactions with sharp, birdlike eyes. That was before Shan’s retrial; they had hoped then that she would soon be released, after she had served the ten years from the first trial. They had not expected that she would be retried for what she had written in her journals in prison, or that words she had put on paper would be enough evidence to warrant a death sentence.

Teacher Gu turned off the light, but the knocking continued. In the darkness he could see the light in his wife’s eyes, more fearful than angry. They were no more than birds that panicked at the first twang of a bow. In a gentle voice Teacher Gu urged, “Let me have the bag.”

She hesitated and then passed the bag to him; he hid it behind the hens’ box, the small noise of their scratching and pecking growing loud in the empty space. From the dark alley occasional creaks of opening gates could be heard, and a few crows stirred on the roof of a nearby house, their croaking carrying a strange conversational tone. Teacher Gu and his wife waited, and when there were no more knocks on the wall, he told her to take a rest before daybreak.

THE CITY OF MUDDY RIVER was named after the river that ran eastward on the southern border of the town. Downstream, the Muddy River joined other rivers to form the Golden River, the biggest river in the northeastern plain, though the Golden River did not carry gold but was rubbish-filled and heavily polluted by industrial cities on both banks. Equally misnamed, the Muddy River came from the melting snow on White Mountain. In summers, boys swimming in the river could look up from underwater at the wavering sunshine through the transparent bodies of busy minnows, while their sisters, pounding laundry on the boulders along the bank, sometimes sang revolutionary songs in chorus, their voices as clear and playful as the water.

Built on a slice of land between a mountain in the north and the river in the south, the city assumed the shape of a spindle. Expansion was limited by both the mountain and the river, but from its center the town spread to the east and the west until it tapered off to undeveloped wilderness. It took thirty minutes to walk from North Mountain to the riverbank on the south, and two hours to cover the distance between the two tips of the spindle. Yet for a town of its size, Muddy River was heavily populated and largely self-sufficient. The twenty-year-old city, a development planned to industrialize the rural area, relied on its many small factories to provide jobs and commodities for the residents. The housing was equally planned out, and apart from a few buildings of four or five stories around the city square, and a main street with a department store, a cinema, two marketplaces, and many small shops, the rest of the town was partitioned into twenty big blocks that in turn were divided into nine smaller blocks, each of which consisted of four rows of eight connected, one-storied houses. Every house, a square of fifteen feet on its sides, consisted of a bedroom and a front room, with a small front yard circled by a wooden fence or, for better-off families, a brick wall taller than a man’s height. The front alleys between the yards were a few feet wide; the back alleys allowed only one person to squeeze through. To avoid having people gaze directly into other people’s beds, the only window in the bedroom was a small square high up on the back wall. In warmer months it was not uncommon for a child to call out to his mother, and for another mother, in a different house, to answer; even in the coldest season, people heard their neighbors’ coughing, and sometimes snoring, through the closed windows.

It was in these numbered blocks that eighty thousand people lived, parents sharing, with their children, brick beds that had wood-stoves built underneath them for heating. Sometimes a grandparent slept there too. It was rare to see both grandparents in a house, as the city was a new one and its residents, recent immigrants from villages near and far, would take in their parents only when they were widowed and no longer able to live on their own.

Except for these lonely old people, the end of 1978 and the beginning of 1979 were auspicious for Muddy River as well as for the nation. Two years earlier, Chairman Mao had passed away and within a month, Madame Mao and her gang in the central government had been arrested, and together they had been blamed for the ten years of Cultural Revolution that had derailed the country. News of national policies to develop technology and the economy was delivered by rooftop loudspeakers in cities and the countryside alike, and if a man was to travel from one town to the next, he would find himself, like the blind beggar mapping this part of the province near Muddy River with his old fiddle and his aged legs, awakened at sunrise and then lulled to sleep at sundown by the same news read by different announcers; spring after ten long years of winter, these beautiful voices sang in chorus, forecasting a new Communist era full of love and progress.

In a block on the western side where the residential area gradually gave way to the industrial region, people slept in row houses similar to the Gus’, oblivious, in their last dreams before daybreak, of the parents who were going to lose their daughter on this day. It was in one of these houses that Tong woke up, laughing. The moment he opened his eyes he could no longer remember the dream, but the laughter was still there, like the aftertaste of his favorite dish, meat stewed with potatoes. Next to him on the brick bed, his parents were asleep, his mother’s hair swirled around his father’s finger. Tong tiptoed over his parents’ feet and reached for his clothes, which his mother always kept warm above the woodstove. To Tong, a newcomer in his own parents’ house, the brick bed remained a novelty, with mysterious and complex tunnels and a stove built underneath.

Tong had grown up in his maternal grandparents’ village, in Hebei Province, and had moved back to his parents’ home only six months earlier, when it was time for him to enter elementary school. Tong was not the only child, but the only one living under his parents’ roof now. His two elder brothers had left home for the provincial capitals after middle school, just as their parents had left their home villages twenty years earlier for Muddy River; both boys worked as apprentices in factories, and their futures—marriages to suitable female workers in the provincial capital, children born with legal residency in that city filled with grand Soviet-style buildings—were mapped out by Tong’s parents in their conversations. Tong’s sister, homely even by their parents’ account, had managed to marry herself into a bigger town fifty miles down the river.

Tong did not know his siblings well, nor did he know that he owed his existence to a torn condom. His father, whose patience had been worn thin by working long hours at the lathe and feeding three teenage children, had not rejoiced when the new baby arrived, a son whom many other households would have celebrated. He had insisted on sending Tong to his wife’s parents, and after a day of crying, Tong’s mother started a heroic twenty-eight-hour trip with a one-month-old baby on board an overcrowded train. Tong did not remember the grunting pigs and the smoking peasants riding side by side with him, but his piercing cries had hardened his mother’s heart. By the time she arrived at her home village, she felt nothing but relief at handing him over to her parents. Tong had seen his parents only twice in the first six years of his life, yet he had not felt deprived until the moment they plucked him out of the village and brought him to an unfamiliar home.

Tong went quietly to the front room now. Without turning on the light, he found his toothbrush with a tiny squeeze of toothpaste on it, and a basin filled with water by the washstand—Tong’s mother never forgot to prepare for his morning wash the night before, and it was these small things that made Tong understand her love, even though she was more like a kind stranger to him. He rinsed his mouth with a quick gurgle and smeared the toothpaste on the outside of the cup to reassure his mother; with one finger, he dabbed some water on his forehead and on both cheeks, the amount of washing he would allow himself.

Tong was not used to the way his parents lived. At his grandparents’ village, the peasants did not waste their money on strange-tasting toothpaste or fragrant soap. “What’s the point of washing one’s face and looking pretty?” his grandfather had often said when he told tales of ancient legends. “Live for thirty years in the wind and the dust and the rain and the snow without washing your face and you will grow up into a real man.” Tong’s parents laughed at such talk. It seemed an urgent matter for Tong’s mother that he take up the look and manner of a town boy, but despite her effort to bathe him often and dress him in the best clothes they could afford, even the youngest children in the neighborhood could tell from Tong’s village accent that he did not belong. Tong held no grudge against his parents, and he did not tell them about the incidents when he was made a clown at school. Turnip Head, the boys called him, and sometimes Garlic Mouth, or Village Bun.

Tong put on his coat, a hand-me-down from his sister. His mother had taken the trouble to redo all the buckles, but the coat still looked more like a girl’s than a boy’s. When he opened the door to the small yard, Ear, Tong’s dog, sprang from his cardboard box and dashed toward him. Ear was two, and he had accompanied Tong all the way from the village to Muddy River, but to Tong’s parents, he was nothing but a mutt, and his yellow shining pelt and dark almond-shaped eyes held little charm for them.

The dog placed his two front paws on Tong’s shoulders and made a soft gurgling sound. Tong put a finger on his lips and hushed Ear. His parents did not awake, and Tong was relieved. In his previous life in the village, Ear had not been trained to stay quiet and unobtrusive. Had it not been for Tong’s parents and the neighbors’ threats to sell Ear to a restaurant, Tong would never have had the heart to slap the dog when they first arrived. A city was an unforgiving place, or so it seemed to Tong, as even the smallest mistake could become a grave offense.

Together they ran toward the gate, the dog leaping ahead. In the street, the last hour of night lingered around the dim yellow street-lamps and the unlit windows of people’s bedrooms. Around the corner Tong saw Old Hua, the rubbish collector, bending over and rummaging in a pile with a huge pair of pliers, picking out the tiniest fragments of used paper and sticking them into a burlap sack. Every morning, Old Hua went through the city’s refuse before the crew of young men and women from the city’s sanitation department came and carted it away.

“Good morning, Grandpa Hua,” Tong said.

“Good morning,” replied Old Hua. He stood up and wiped his eyes; they were bald of eyelashes, red and teary. Tong had learned not to stare at Old Hua’s afflicted eyes. They had looked frightening at first, but when Tong had got to know the old man better, he forgot about them. Old Hua treated Tong as if he was an important person—the old man stopped working with his pliers when he talked to Tong, as if he was afraid to miss the most interesting things the boy would say. For that reason Tong always averted his eyes in respect when he talked to the old man. The town boys, however, ran after Old Hua and called him Red-eyed Camel, and it saddened Tong that the old man never seemed to mind.

Old Hua took a small stack of paper from his pocket—some ripped-off pages from newspapers and some papers with only one side used, all pressed as flat as possible—and passed them to Tong. Every morning, Old Hua kept the clean paper for Tong, who could read and then practice writing in the unused space. Tong thanked Old Hua and put the paper into his coat pocket. He looked around and did not see Old Hua’s wife, who would have been waving the big bamboo broom by now, coughing in the dust. Mrs. Hua was a street sweeper, employed by the city government.

“Where is Grandma Hua? Is she sick today?”

“She’s putting up some announcements first thing in the morning. Notice of an execution.”

“Our school is going to see it today,” Tong said. “A gun to the bad man’s head. Bang.”

Old Hua shook his head and did not reply. It was different at school, where the boys spoke of the field trip as a thrilling event, and none of the teachers opposed their excitement. “Do you know the bad man in the announcement?” Tong asked Old Hua.

“Go and look,” Old Hua said and pointed down the street. “Come back and tell me what you think.”

At the end of the street Tong saw a newly pasted announcement, the two bottom corners already coming loose in the wind. He found a rickety chair in front of a yard and dragged it over and climbed up, but still he was not tall enough, even on tiptoes, to reach the bottom of the paper. He gave up and let the corners flap on their own.

The light from the streetlamps was weak, but the eastern sky had taken on a hue of bluish white like that of an upturned fish belly. Tong read the announcement aloud, skipping the words he did not know how to pronounce but guessing their meanings without much trouble:

Counterrevolutionary Gu Shan, female, twenty-eight, was sentenced to death, with all political rights deprived. The execution will be carried out on the twenty-first of March, nineteen seventy-nine. For educational purposes, all schools and work units are required to attend the pre-execution denunciation ceremony.

At the bottom of the announcement was a signature, two out of three of whose characters Tong did not recognize. A huge check in red ink covered the entire announcement.

“You understand the announcement all right?” asked the old man, when Tong found him at another bin.

“Yes.”

“Does it say it’s a woman?”

“Yes.”

“She is very young, isn’t she?”

Twenty-eight was not an age that Tong could imagine as young. At school he had been taught stories about young heroes. A shepherd boy, seven and a half years old, not much older than Tong, led the Japanese invaders to the minefield when they asked him for directions, and he died along with the enemies. Another boy, at thirteen, protected the property of the people’s commune from robbery and was murdered by the thief. Liu Hulan, at fifteen and a half, was executed by the White Army as the youngest Communist Party member of her province, and before she was beheaded, she was reported to have sneered at the executioners and said, “She who works for Communism does not fear death.” The oldest heroine he knew of was a Soviet girl named Zoya; at nineteen she was hanged by the German Fascists, but nineteen was long enough for the life of a heroine.

“Twenty-eight is too early for a woman to die,” Old Hua said.

“Liu Hulan sacrificed her life for the Communist cause at fifteen,” replied Tong.

“Young children should think about living, not about sacrificing,” Old Hua said. “It’s up to us old people to ponder death.”

Tong found that he didn’t agree with the old man, but he did not want to say so. He smiled uncertainly, and was glad to see Ear trot back, eager to go on their morning exploration.

EVEN THE TINIEST NOISE could wake up a hungry and cold soul: the faint bark of a dog, a low cough from a neighbor’s bedroom, footsteps in the alley that transformed into thunder in Nini’s dreams while leaving others undisturbed, her father’s snore. With her good hand, Nini wrapped the thin quilt around herself, but hard as she tried, there was always part of her body exposed to the freezing air. With the limited supply of coal the family had, the fire went out every night in the stove under the brick bed, and sleeping farthest from the stove, Nini had felt the coldness seeping into her body through the thin cotton mattress and the layers of old clothes she did not take off at bedtime. Her parents slept at the other end, where the stove, directly underneath them, would keep them warm for the longest time. In the middle were her four younger sisters, aged ten, eight, five, and three, huddled in two pairs to keep each other warm. The only other person awake was the baby, who, like Nini, had no one to cuddle with for the night and who now was fumbling for their mother’s breast.

Nini got out of bed and slipped into an oversize cotton coat, in which she could easily hide her deformed hand. The baby followed Nini’s movement with bright, expressionless eyes, and then, frustrated by her futile effort, bit with her newly formed teeth. Their mother screamed, and slapped the baby without opening her eyes. “You debt collector. Eat. Eat. Eat. All you know is eating. Were you starved to death in your last life?”

The baby howled. Nini frowned. For hungry people like the baby and Nini herself, morning always came too early. Sometimes she huddled with the baby when they were both awake, and the baby would mistake her for their mother and bump her heavy head into Nini’s chest; those moments made Nini feel special, and for this reason she felt close to the baby and responsible for all that the baby could not get from their mother.

Nini limped over to the baby. She picked her up and hushed her, sticking a finger into the baby’s mouth and feeling her new, beadlike teeth. Except for Nini’s first and second sisters, who went to elementary school now, the rest of the girls, like Nini herself, did not have official names. Her parents had not even bothered to give the younger girls nicknames, as they did to Nini; they were simply called “Little Fourth,” “Little Fifth,” and, the baby, “Little Sixth.”

The baby sucked Nini’s finger hard, but after a while, unsatisfied, she let go of the finger and started to cry. Their mother opened her eyes. “Can’t you both be dead for a moment?”

Nini shuffled Little Sixth back to bed and fled before her father woke up. In the front room Nini grabbed the bamboo basket for collecting coal and stumbled on a pair of boots. A few steps into the alley, she could still hear the baby’s crying. Someone banged on the window and protested. Nini tried to quicken her steps, her crippled left leg making bigger circles than usual, and the basket, hung by the rope to her shoulder, slapped on her hip with a disturbed rhythm.

At the end of the alley Nini saw an announcement on the wall. She walked closer and looked at the huge red check. She did not recognize a single character on the announcement—her parents had long ago made it clear that for an invalid like her, education was a waste of money—but she knew by the smell that the paste used to glue the announcement to the wall was made of flour. Her stomach grumbled. She looked around for a step stool or some bricks; finding none, she set the basket on the ground with its bottom up and stepped onto it. The bottom sagged but did not give way under her weight. She reached a corner of the announcement with her good hand and peeled it off the wall. The flour paste had not dried or frozen yet, and Nini scraped the paste off the announcement and stuffed all five fingers into her mouth. The paste was cold but sweet. She scraped more of it off the announcement. She was sucking her fingers when a feral cat pounced off a wall and stopped a few feet away, examining her with silent menace. She hurried down from the basket, almost falling onto her bad foot, and sending the cat scurrying away.

At the next street corner Nini caught up with Mrs. Hua, who was brushing paste on the four corners of an announcement when the girl walked up.

“Good morning,” the old woman said.

Nini looked at the small basin of paste without replying. Sometimes she greeted Mrs. Hua nicely, but when she was in a bad mood, which happened often, she sucked the inside of her mouth hard so that no one could make her talk. Today was one of those days—Little Sixth had caused trouble again. Of all the people in the world, Nini loved Little Sixth best, yet this love, a heavy knot in her stomach, as Nini sometimes felt it, could not alleviate her hunger.

“Did you have a good sleep?”

Nini did not reply. How did Mrs. Hua expect her to sleep well when she was always starving? The few mouthfuls of paste had already vanished, and the slight sweet taste in her mouth made her hungrier.

The old woman took a leftover bun from her pocket, something she made sure to bring along every morning in case she saw Nini, though the girl would never know this. Nini reminded Mrs. Hua of the daughters she had once had, all of those girls discarded by their parents. In another life she would have adopted Nini and kept her warm and well fed, Mrs. Hua thought. It seemed that not too long ago life had been a solid dam for her and her husband—with each baby girl they had picked up in their vagrancy, they had discovered once and again that, even for beggars, life was not tightfisted with moments of exhilaration—but the dam had been cracked and taken over by flood, their happiness wiped out like hopeless lowland. Mrs. Hua watched Nini take a big bite of the bun, then another. A few bites later, the girl started to hiccup.

“You are eating too fast,” Mrs. Hua said. “Remember to chew.”

When half of the bun was gone, Nini slowed down. Mrs. Hua went back to the announcement. Years of sweeping the street and, before that, wandering from town to town and rummaging through the refuse had given the old woman’s back a permanent stoop, but still she was unusually tall, towering over most men and other women. Perhaps that was why the old woman got the job, Nini thought, to put the announcements out of people’s reach so nobody could steal the paste.

Mrs. Hua patted the corners of the announcement onto the wall. “I’m off to the next street,” she said.

Nini did not move, looking sharply at the basin of paste in Mrs. Hua’s hand. The old woman followed Nini’s eyes and shook her head. Seeing nobody in the street, she took a sheet from the pile of announcements and folded it into a cone. “Take it,” she said and placed the cone in Nini’s good hand.

Nini watched Mrs. Hua scoop some paste into the paper cone. When there was no sign of any more, Nini licked her hand clean of the dribbles. Mrs. Hua watched her with unspeakable sadness. She was about to say something, but Nini began to walk away. “Nini, throw the paper cup away after you finish it,” the old woman said in a low voice behind her. “Don’t let people see you are using the announcement.”

Nini nodded without looking back. Between hiccups she was still biting the inside of her mouth hard, making sure she did not say a word more than necessary. She did not understand Mrs. Hua’s kindness toward her. She accepted the benevolence of the world, as much as she did its cruelty, just as she was resigned to her body being born deformed. Knowledge of human beings came to Nini from eavesdropping on tales—her parents, in their best mood, walked around her as if she were a piece of furniture, and other people seemed to be able to ignore her existence. This meant Nini could learn things that other children were not allowed to hear. At the marketplace, housewives talked about “bedroom business” with loud giggles; they made mean jokes about the teenage peddlers from the mountain villages, who, new in their business, tried hard not to notice the women’s words yet often betrayed themselves by blushing. The neighbors, after a day’s work and before dinner, gathered in twos and threes in the alley and exchanged gossip, Nini’s existence nearby never making them change topics hurriedly, as another child walking past would do. She heard stories of all kinds—a daughter-in-law mixing shredded grass into the dumpling filling for her mother-in-law, a nanny slapping and permanently deafening a baby, a couple making too much noise when they made “bedroom business,” so that the neighbor, a mechanic working at the quarry, installed a mini – time bomb to shock the husband’s penis into cotton candy—such tales bought Nini pleasures that other children obtained from toys or games with companions, and even though she knew enough to maintain a nonchalant expression, the momentary freedom and glee offered by eavesdropping were her closest experiences of a childhood that was unavailable to her, a loss of which she was not aware.

The six-thirty freight train whistled. Every morning, Nini went to collect coal at the train station. The Cross-river Bridge, the only one connecting the town to the other bank of the Muddy River, had four lanes, but at this early hour, trucks and bicycles were scarce. The only other pedestrians were women and teenage peasants coming down the mountains, with newly laid eggs kept warm in their handkerchiefs, small tins of fresh milk from goats and cows, and homemade noodles and pancakes. Walking against the flow of the peasants, Nini eyed them with suspicion as they looked back at her, not bothering to hide their revulsion at the sight of her deformed face.

The railway station near the Cross-river Bridge was a stop for freight only. Coal, timber, and aluminum ore from the mountains were loaded here and carried on to big cities. The passenger trains stopped at a different station on the west end of the town, and sometimes, standing on the bridge, Nini saw them rumble past, people’s faces visible in the many squares of windows. Nini always wondered what it felt like to go from one place to another in the blink of an eye. She loved speed—the long trains whose clinking wheels sparked on the rail; the jeeps with government plate numbers, racing even in the most crowded streets, stirring up dust in the dry season, splattering mud when it was raining; the ice drifts flowing down the Muddy River in the spring; the daredevil teenage boys on their bicycles, pedaling hard while keeping both hands off the handlebars.

Nini quickened her steps. If she did not get to the railway station fast enough, the workers would have transferred the coal from trucks to the freight cars. Every morning, the workers, out of intentional carelessness, would drop some coal to the ground, and later would divide it among themselves. Nini’s morning chore was to stand nearby, staring and waiting until one of the workers finally acknowledged her presence and gave her a small share of the coal. Everyone worked for her food, Nini’s mother had said many times, and all Nini wanted was to reach the station in time, so she would not be denied her breakfast.

WALKING ACROSS THE BRIDGE in the opposite direction from Nini, among the clusters of peasants, Bashi was deep in thought and did not see the girl, nor did he hear two peasant women commenting on Nini’s misshapen face. He was preoccupied in his imagination with what a girl was like down there between her legs. Bashi was nineteen, had never seen a girl’s private parts, and was unable to picture what they would be like. This, for Bashi, son of a Communist hero—the reddest of the red seeds—was an upsetting deficiency.

Bashi’s father had served in the Korean War as one of the first pilots of the nation, and had been awarded many titles as a war hero. The American bombs had not killed him but a small human error had—he died from a tonsillectomy the year Bashi was two. The doctor who injected the wrong anesthesia was later sentenced to death for subverting the Communist nation and murdering one of its best pilots, but what happened to the doctor, whether it had been a life or a death sentence, meant little to Bashi. His mother had left him to his paternal grandmother and remarried herself into another province, and ever since then his life had been subsidized by the government. The compensation, a generous sum compared to other people’s earnings, made it possible for his grandmother and him to live in modest comfort. She had hoped he would be a good student and earn a decent living by his wits, but that did not happen, as Bashi had little use for his education. She worried and nagged at him, but he forgave her because she was the only person who loved him and whom he loved back. Someday she would die—her health had been deteriorating over the past two years, and her brain was muddled now with facts and fantasies that she could not tell apart. Bashi did not look forward to the day she would leave him for the other side of the world, but in the meantime, he was aware that the house, although owned by the government, would be his to occupy as long as he lived, and the money in their savings account would be enough to pay for his meals and clothes and coal without his having to lift a finger. What else could he ask of life? A wife for sure, but how much more food could she consume? As far as Bashi was concerned, he could have a comfortable life with a woman, and neither of them would have to make the slightest effort to work.

The problem, then, was how to find a woman. Apart from his grandmother, Bashi had little luck with other women. Older ones, those his grandmother’s or his mother’s age, used him as a warning for their offspring. They would be too ashamed to meet their ancestors after their deaths if it turned out that they would have to endure a son, or a grandson, like Bashi—these comments, often loud enough for Bashi to hear, were directed at those children who needed a cautionary tale. Younger women of a suitable age for marriage avoided Bashi as a swan princess in the folktales would avoid a toad. It was Bashi’s belief that he needed to gain more knowledge of a woman’s body before he could gain access to her heart, but who among the young women looking at him despisingly would open up her secrets to him?

Bashi’s hope now lay with much younger girls. He had already made several attempts, offering little girls from different neighborhoods candies, but none of them had agreed to go with him into the high grasses by the riverbank. Even worse, one of the girls told her parents, and they gave him a good beating and spread the news around so that wherever he went now, he felt that people with daughters were keeping a watchful eye on him. The little girls made up a song about him, calling him a wolf and skunk and girl-chasing eel. He was not offended; rather, he liked to walk into the girls’ circle in the middle of their games, and he would smile when they chanted the song to his face. He imagined taking them one by one to a secret bush and studying what he needed to study with them, and he smiled more delightedly since none of the girls would ever have guessed what could have been happening to them at that very moment, these young girls singing for him in their fine, lovely voices.

Bashi had other plans too. For instance, hiding in the public outhouse after midnight, or in the early morning, when females would arrive in a hurried, half-dreaming state, too sleepy to recognize him as he squatted in a place where the light from the single bulb did not reach. But the idea of squatting for a long stretch of time, cold, tired, and stinking, prevented Bashi from carrying out this plan. He might as well dress up in his grandma’s clothes and wrap his head in a shawl to go to a public bathhouse. He could talk in a high-pitched voice and ask for a ticket to the women’s section, go into the locker room and feast his eyes on the women undressing. He could stay for a while and then pretend he had to go home to take care of some important things, a chicken stewing on the stove maybe, or some forgotten laundry on the clothesline.

Then there were other possibilities that offered more permanent hope, like finding a baby girl on the riverbank, which was what Bashi was trying to do now. He had searched the bank along the railway track, and now he walked slowly on the town side of the river and looked behind every boulder and tree stump. It was unlikely that someone would leave a baby girl out here in this cold season, but it never hurt to check. Bashi had found a baby girl, one February morning two years earlier, underneath the Cross-river Bridge. The baby had been frozen stiff, if not by the cold night, then by death itself. He had studied its gray face; the thought of opening the blanket and looking underneath the rags, for some reason, chilled him, so he left it where it had been deserted. He went back to the spot an hour later, and a group of people had gathered. A baby girl it must be, people said, a good solid baby but what a pity it wasn’t born a boy. It takes only a few layers of wet straw paper, and no more than five minutes, people said, as if they had all suffocated a baby girl at least once in their lives, talking about the details in that vivid way. Bashi tried to suggest that the baby might have frozen to death, but nobody seemed to hear him. They talked among themselves until Old Hua and his wife came and put the small bundle of rags into a burlap sack. Bashi was the only one to accompany the Huas to where they buried deserted babies. Up the river at the western end of town it was, where white nameless flowers bloomed all summer long, known to the children in town as dead-baby flowers. On that day the ground was too frozen to dig even the smallest hole; the couple found a small alcove behind a rock, and covered the baby up with dry leaves and dead grass, and then marked the place. They would come back later to bury her, they told Bashi, and he replied that he had no doubt they would send her off properly, good-hearted people as they were, never letting down a soul.

Bashi believed that if he waited long enough, someday he would find a live baby on the riverbank. He did not understand why people did not care for baby girls. He certainly wouldn’t mind taking one home, feeding her, bathing her, and bringing her up, but such a plan he had to keep secret from his townsfolk, who treated him as an idiot. And idiocy seemed to be one of the rare crimes for which one could never get enough punishment. A robber or a thief got a sentence of a year or more for a crime, but the tag of idiot, just as counterrevolutionary, was a charge against someone’s very being, and for that reason Bashi did not like his fellow townsfolk. Even a counterrevolutionary sometimes got depurged, as he often heard these days. There were plenty of stories on the radio about so-and-so who had been wronged in the Cultural Revolution and was reabsorbed into the big Communist family, but for Bashi, such redemption seemed beyond reach. People rarely paid attention to him when he joined a conversation at an intersection or a roadside chess party on summer evenings, and when they did, they all held disbelieving and bemused smiles on their faces, as if he made them realize how much more intelligent they themselves were. Bashi had often made up his mind never to talk to these people, but the next time he saw these gatherings, he became hopeful again. Despite being badly treated, he loved people, and loved talking to them. He dreamed of the day when the townspeople would understand his importance; perhaps they would even grab his hands and shoulders and apologize for their mistake.

A dog trotted across to the riverbank, its golden fur shimmering in the morning light. In its mouth was a paper cone. Bashi whistled to the dog. “Ear, here, what treasure did you find?”

The dog looked at Bashi and stepped back. The dog belonged to a newcomer in town, and Bashi had studied both the dog and the boy. He thought Ear a strange name for a dog, and believed the boy who had named it must have something wrong with him. They were two of a kind, village-grown and not too bright. Bashi put a hand into his pocket, and said in a gentle voice, “A bone here, Ear.”

The dog hesitated and did not come to Bashi. He held the dog’s eyes with his own and inched closer, calling out again in his gentle voice, then without warning he picked up a rock and hurled it at the dog, which gave out a short yelp and ran away, dropping the paper cone on the ground. Bashi continued to hurl rocks in the direction where the dog had disappeared. Once before, he had been able to lure Ear closer so he could give it a good kick in its belly.

Bashi picked up the paper cone and spread it on the ground. The ink was smeared, but the message was clear. “A counterrevolutionary is not a game,” Bashi said aloud. The name on the announcement sounded unfamiliar, and Bashi wondered if the woman was from town. Whose daughter was she? The thought of someone’s daughter being executed was upsetting; no crime committed by a young woman should lead to such a horrible ending, but was she still a maiden? Bashi read the announcement again; little information was given about this Gu Shan. Perhaps she was married—a twenty-eight-year-old was not expected to remain a girl, except …“A spinster?” Bashi spoke aloud to finish his thought. He wondered what the woman had done to earn herself the title of counterrevolutionary. The only other person he knew who had committed a similar crime was the doctor who had killed his father. Bashi read the announcement again. Her name sounded nice, so perhaps she was just someone like him, someone whom nobody understood and no one bothered to understand. What a pity she would have to die on the day he discovered her.

TONG CALLED OUT Ear’s name several times before the dog reappeared. “Did you bother the black dog again?” Tong asked Ear, who was running toward Tong in panic. The black dog belonged to Old Kwen, a janitor for the electric plant who, unlike most people living in the blocks, occupied a small, run-down shack at the border between the residential and industrial areas. Old Kwen and his dog were among the few things Tong’s father had told him about the town when Tong had first arrived. Leashed all its life in front of the shack and allowed to move only in a radius of less than five feet, the dog was said to be the meanest and the best guard dog in town, ready to knock down and bite through the throat of anyone who dared to set foot near his master’s shack; stay away from a man who keeps a dog like this, Tong’s father had warned him, but when Tong asked why, his father did not give an explanation.

Too curious and too friendly, Ear had approached the black dog several times, and each time the black dog had growled and jumped up, pulling at the end of his chain with fierce force; it would then take Tong a long time to calm Ear down. “You have to learn to leave other dogs alone,” Tong said now, but Ear only whined. Maybe he was chastising Ear for the wrong reason, Tong thought, and then he realized that he hadn’t heard the black dog bark. “Well, maybe it’s not the black dog, but someone else. You have to learn to leave others alone. Not all of them love you as you think they do,” Tong said.

They walked on the riverbank. The clouds were heavy in the sky. The wind brought a stale smell of old, unmelted snow. Tong stripped a layer of pale, starchy bark off a birch tree, and sat down with his stump of pencil. He wrote onto the bark the words he remembered from the announcement: Female. Counterrevolutionary. School.

Tong was one of the most hardworking students in his class. The teacher sometimes told the class that Tong was a good example of someone who was not bright but who made up for his shortcoming by thorough work. The comment had left Tong more sad than proud at first, but after a while he learned to cheer himself up: After all, praise from the teacher was praise, and an accumulation of these favorable comments could eventually make him an important pupil in the teacher’s eyes. Tong longed to be one of the first to join the Communist Young Pioneers after first grade so that he would earn more respect from the townspeople, and to realize that dream he needed something to impress his teachers and his peers. He had thought of memorizing every character from the elementary dictionary and presenting the result to the teacher at the end of the semester, but his parents, both workers, were not wealthy enough to give him an endless supply of exercise books. The idea of using the birch bark had occurred to Tong after he had read in a textbook that Comrade Lenin, while imprisoned, had used his black bread as an ink pot and his milk as ink, and had written out secret messages to his comrades; on the margins of newspapers, the messages would show up only when the newspaper was put close to fire; whenever a guard approached Lenin would devour his ink pot with the ink in it. “If you have a right heart, you’ll find the right way,” the teacher said of the story’s moral. Since then Tong had tried to keep the right heart and had gathered a handful of pencil stumps that other children had discarded. He had also discovered the birch bark, perfect for writing, a more steady supply than the paper Old Hua saved for him.

Ear sat down on his hind legs and watched Tong work for a while. Then the dog leapt out to the frozen river, leaving small flowerlike paw prints on the old snow. Tong wrote until his fingers were too cold to move. He blew big white breaths on them, and read the words to himself before putting away his pencil stump.

Tong looked back at the town. Red flags waved on top of the city hall and the courthouse. At the center of the city square, a stone statue of Chairman Mao dwarfed the nearby five-storied hospital. According to the schoolteachers, it was the tallest statue of Chairman Mao in the province, the pride of Muddy River, and had attracted pilgrims from other towns and villages. It was the main reason that Muddy River had been promoted from a regional town to a city that now had governing rights over several surrounding towns and villages. A few months earlier, not long after Tong’s arrival, a worker assigned to the semiannual cleaning of the statue had an accident and plummeted to his death from the shoulder of Chairman Mao. Many townspeople gathered. Tong was one of the children who had squeezed through the legs of adults to have a close look at the body—the man, in the blue uniform of a cleaning worker, lay face up with a small puddle of blood by his mouth; his eyes were wide open and glassy-looking, and his limbs stuck out at odd and impossible angles. When the orderlies from the city hospital came to gather the body, it slipped and shook as if it were boneless, reminding Tong of a kind of slug in his grandparents’ village—their bodies were fleshy and moist, and if you put a pinch of salt on their bodies, they would slowly become a small pool of white and sticky liquid. The child standing next to him was sick and was whisked away by his parents, and Tong willed himself not to act weakly. Even some grown-ups turned their eyes away when the orderlies had to peel the man’s head off the ground, but Tong forced himself to watch everything without missing a single detail. He believed if he was brave enough, the town’s boys, and perhaps the grown-ups too, would approve of him and accept him as one of the best among them. It was not the first time that Tong had seen a dead body, but never before had he seen a man die in such a strange manner. Back in his grandparents’ village, people died in unsurprising ways, from sickness and old age. Only once a woman, working in the field with a tank of pesticide on her back, was killed instantly when the tank exploded. Tong and other children had gathered at the edge of the field and watched the woman’s husband and two teenage sons hose down the body from afar until the fire was put out and the deadly gas dispersed; they seemed in neither shock nor grief, their silence suggesting something beyond Tong’s understanding.

Some people’s deaths are heavier than Mount Tai, and others’ are as light as a feather. Tong thought about the lesson his teacher had taught a few weeks before. The woman killed in the explosion had become a tale that the villagers enjoyed telling to passersby, and often the listeners would exclaim in awe, but would that give her death more weight than an old woman dying in her sleep in the lane next to Tong’s grandparents’? The counterrevolutionary’s death must be lighter than a feather, but the banners and the ceremony of the day all seemed to say differently.

The city came to life in the boy’s baffled gaze, some people more prepared than others for this important day. A fourth grader found to her horror that her silk Young Pioneer’s kerchief had been ripped by her little brother, who had bound it around his cat’s paw and played tug-of-war with the cat. Her mother tried to comfort her—didn’t she have a spare cotton one, her mother asked, and even if she wore the silk kerchief, nobody would notice the small tear—but nothing could stop the girl’s howling. How could they expect her, a captain of the Communist Young Pioneers in her class, to wear a plain cotton kerchief or a ripped one? The girl cried until it became clear that her tears would only make her look worse for the day; for the first time in her life, she felt its immense worthlessness, when a cat’s small paw could destroy the grandest dream.

A few blocks away, a truck driver grabbed his young wife just as she rose from bed. One more time, he begged; she resisted, but when she failed to free her arms from his tight grip, she lay open for him. After all, they could both take an extra nap at the denunciation ceremony, and she did not need to worry about his driving today. In the city hospital, a nurse arrived late for the morning shift because her son had overslept, and in a hurry to finish her work before going to the denunciation ceremony, she gave the wrong dose of antibiotics to an infant recovering from pneumonia; only years later would the doctors discover the child’s deafness, caused by the mistake, but it would remain uninvestigated, and the parents would have only fate to blame for their misfortune. Across the street in the communication building, the girl working the switchboard yelled at a peasant when he tried to call his uncle in a neighboring province; didn’t he know that today was an important day and she had to be fully prepared for the political event instead of wasting her time with him, she said, her harsh words half-lost in a bad connection; while she was berating him, the army hospital from the provincial capital called in, and this time the girl was shouted at because she was not prompt enough in picking up the call.

TWO (#ulink_9dd5566a-aeba-5bbd-ac33-6bc08b6b99b0)

The girl was dressed in a dark-colored man’s suit, a size too big for her, her hair coiled up and hidden underneath a fedora hat of matching color. Her hands, clad in black gloves, held tightly on to the handle of a short, unsheathed sword. The blade pointed upward, the only object of light color in the black-and-white picture. The girl’s unsmiling face was half shadowed by the hat, her eyes looking straight into the camera. Think of how Autumn Jade was prepared to give up her life, Kai remembered her teacher explaining when she was chosen to play the famous heroine in a new opera. Kai was twelve then, a rising star in the theater school at the provincial capital, and it was not a surprise that she was given every major role, from Autumn Jade, who had been beheaded after a failed assassination of a provincial representative in the last emperor’s court, to Chen Tiejun, the young Communist who had been shot alongside her lover shortly after they had announced each other husband and wife in front of the firing squad. Kai had always been praised for her mature performances, but looking at her picture now, she could see little understanding in the girl’s eyes of the martyrs she had impersonated. Kai had once taken pride in entering adulthood ahead of her peers, but that adulthood, she could see now, was as false and untrustworthy as her youthful interpretation of death and martyrdom.

She returned the framed picture to the wall where it had hung for the past five years along with other pictures, relics of her life onstage between the ages of twelve and twenty-two. The studio, a small, windowless room on the top floor of the administration building, with padded walls and flickering fluorescent lights, had struck Kai at first as a place not much different from a prison cell. Han was the one who decorated the room, hanging up her pictures on the walls and a heart-shaped mirror behind the door, placing vases of plastic flowers on the shelves so they could bloom all year round without the need for sunshine or other care—to make the studio her very own, as Han insisted—when he helped her get the news announcer’s position. One more reason to consider his marriage proposal, Kai’s mother urged, thinking of other less privileged jobs that Kai could have been assigned to after her departure from the provincial theater troupe: teaching in an elementary school and struggling to make the children sing less cacophonously, or serving as one of those clerks who had little function other than filling the offices with pleasant feminine presence in the Cultural and Entertainment Department. Han, the only son of one of the most powerful couples in the city government, had been courting Kai for six months then, a perfect choice for her, according to her parents, who, both as middle-ranked clerks, had little status to help Kai, when younger faces had replaced Kai onstage. The most important success for a woman is not in her profession but in her marriage, Kai’s father said when she thought of leaving Muddy River and seeking an acting career in Beijing or Shanghai; it is more of a challenge to retain the lifelong attention of one audience than to win the hearts of many who would forget her overnight. In her mother’s absence, Kai’s father explained all this, and it was not only his insight into the ephemeral nature of fame but also his unmistakable indication that Kai’s mother—the more dominating and abusive one in their marriage—had failed, that made Kai reconsider her decision. A child who catches for the first time a glimpse of the darker side of her parents’ marriage is forced to enter the grown-up world, often against her nature and will, just as she was once pushed through a birth canal to claim her existence. For Kai, who had left home for the theater school at eight, this second birth came at a time when most of her school friends had ventured into marriage and early motherhood, and she made up her mind to marry into Han’s family. That Kai’s father had passed away shortly thereafter with liver cancer, discovered at a stage too late, had made the decision seem a worthy one, at least for the first year of the marriage.

Kai placed a record on the phonograph. The needle circled on the red disc, and dutifully the theme song for the morning news, “Love of the Homeland,” flooded out of loudspeakers onto every street corner. Kai imagined the world outside the broadcast studio: the dark coal smoke rising from rooftops into the lead-colored morning sky; sparrows jumping from one roof to the next, their wings dusty and their chirping drowned out by the patriotic music; the people underneath those roofs, used to the morning ritual of music and then the news broadcast. They would probably not hear a single word of the program.

The chorus ended, and Kai lifted the needle and turned on the microphone. “Good morning, workers, peasants, and all revolutionary comrades of Muddy River,” she began in her standard greeting, her well-trained voice at once warm and impersonal. She reported both international and national news, taken from People’s Daily and Reference Journal by a night-shift clerk in the propaganda department, followed by provincial news and local affairs. Afterward she picked up an editorial, denouncing the Vietnamese government for its betrayal of the true Communist faith, and hailing the ideological importance of Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge despite the temporary setback brought about by the Vietnamese intrusion. While she was reading, Kai was aware of the note taped to the microphone, instructing her to announce to the townspeople Gu Shan’s denunciation ceremony, and her execution to follow.

Gu Shan was twenty-eight, the same age as Kai, and four years younger than Autumn Jade when she had been beheaded after a hasty trial. Autumn Jade had left two children who were too young to mourn her death, and a husband who had disowned her in defense of the last dynasty she had been fighting against. Kai had a husband and a son; Gu Shan had neither. The freedom to sacrifice for one’s belief was a luxury that few could afford, Kai thought. She imagined sneaking the words pioneer and martyr into the announcement of the execution. Would Shan, who was probably being offered her last breakfast and perhaps a change of clean clothes, hear the voice of a friend she had perhaps long ago ceased hoping for in her long years of imprisonment? Kai’s hands shook when she read the announcement. She and Shan were allies now, even though Shan would never know it.

Kai clicked off the microphone, and someone promptly knocked on the door, two short taps followed by a scratch. Kai checked her face in the mirror before opening the door.

“The best tonic for the best voice,” said Han, as he lifted the thermos and presented it with a theatrical gesture. Every morning, before Han went to his office in the same building, he stopped by the studio with a thermos of tea, brewed from an herb named Big Fat Sea and said to be good for one’s voice. It had begun as a habit of love after their honeymoon, and Kai had thought that it would cool down and eventually die as all unreasonable passions between a man and woman did. But five years and a child later, Han had not given up the practice. He must be the only husband in this town who would deliver tea to his wife, Han sometimes said, full of marvel and admiration, as if he himself was happily baffled by what he did; other people must think of him as a fool now, he said, out of self-mockery, yet it was the pride he did not conceal in the statement that filled Kai with panic. Getting married and becoming a mother had once seemed the most natural course for her life, but Kai could not help but wish, at times, that everything she had mistakenly decided could be wiped away.

“I’ve told you many times I don’t need it,” said Kai of the tea, and her reply, which often sounded like a loving reprimand, sounded more impatient to her ears today. Han seemed not to notice. He pecked her on the cheek, walked past her into the studio, and poured a mug of tea for her. “It’s an important day. I don’t want the world to hear that my wife’s voice is anything less than perfect.”

Kai smiled weakly, and when Han urged her to drink the tea, she took a sip. He gazed at her. How was his preparation for the day going, she asked, before he had a chance to compliment her beauty, as he often did.

“All set but for the helicopter,” Han replied.

The helicopter? Kai asked. Something that was not his responsibility, he said, and he left it at that. Kai asked, as if out of innocent curiosity, what he needed a helicopter for, and Han replied that he was sure someone would set things straight, she should not bother herself with his boring business. “Worrying makes one grow old,” he said, as a joke, and Kai said that perhaps it would soon be time for him to look for a younger woman. He laughed, taking Kai’s reply as a flirtation.

It amazed her that her husband never doubted her in any way. His faith and confidence in her—and more so in himself—made him a blind worshipper of their marriage. How easy it was to deceive a trusting soul, but the thought unsettled Kai. She looked at the clock, and said it was about time for her to go. She was expected to be at her position at the East Wind Stadium, one of the major sites for the denunciation ceremony, by eight. He would walk her there, Han said. Kai wished she had an excuse to reject his offer, but she said nothing.

She put a few pages of the news away and adjusted her hair before leaving the studio with him. Her husband placed a hand on her elbow, as if she needed his guidance and assistance to walk down the five flights of stairs, but when they exited the building, he let go of her, so that they would not be seen having any improper physical contact in public.

“So I’ll see you at Three Joy?” Han asked, as they turned at the street corner.

What for? Kai asked, and Han answered that it was the celebration banquet. Nobody had told her about it, Kai said, and Han replied that he thought she would have known by now that it was the regular thing after such an event. “The last couple of dinners, the mayor asked why you were not there,” Han said, and added that he had found excuses for her both times.

Kai could envision it: her place at the table with the mayor and his wife, Han and his parents and a few other families, a close-knit circle of status. It had been part of the allure of the marriage, that once she was a member of this family she would enter a social group that clerks like her parents had dreamed of reaching all their lives. Kai was unwilling to admit it now, but she knew that vanity was one of her costly errors. She was a presentable wife and daughter-in-law: good-looking, having had no other boyfriend before she met Han, and capable of giving birth to a son for the first baby. Her in-laws treated her well, but they would never hesitate to let her know that she was the one to have married up in the family.

She had told the nanny that she would be home around lunchtime, Kai said. The new nanny, having just started the week before, was fifteen and a half, too young to take care of a baby, in Kai’s opinion, but when the previous nanny had quit to go back to work on the land with her husband and sons—after many years of the people’s commune, the central government had finally allowed peasants to own the planting rights to their own land—a girl from the mountain village was the only one they could find as a replacement.

He would send his parents’ orderly to check on the nanny, Han said. What could an eighteen-year-old boy know about an eleven-month-old baby, Kai responded, and Han, detecting a trace of impatience in her words, studied her and asked if she was feeling all right. He squeezed her hand quickly before letting it go.

Kai shook her head and said she only worried about Ming-Ming. Han replied that he understood, but his parents would not be happy if she missed important social events. She nodded and said she would go if that was what he wanted. The baby had been an easy excuse for her distraction at the breakfast table, the dinners she missed at Han’s parents’ flat, fewer visits to her own mother, her tired apologies when Han asked for sex at night.

“My parents want you to be there,” said Han. “So do I.”

Kai nodded, and they resumed their walk in silence. A few blocks away they saw smoke rising at an intersection. A group of people had gathered, and there was a strong odor of burned leather in the air. A piece of silk, palm-sized and in a soft faded color, was carried across the street by the wind. An orange cat, stretching on a low wall, followed the floating fabric with its eyes.

Han asked the crowd to make way. A few people stood aside, and Kai followed her husband into the circle. A man sporting the red armband of the Workers’ Union security patrol was staring down at an old woman, who sat in front of a burning pile of clothes. She did not look up when Han asked her why she was blocking traffic on the important day of a political event.

“The old witch is playing deaf and mute,” the security patrol said, and added that his companion had gone to fetch the police.

Kai looked at the top of the old woman’s head, barely covered by thin gray hair. She bent down toward the old woman, and told her that she was violating a traffic regulation, that she’d better leave now. There was a slight ripple in the crowd as Kai spoke; in this town, people recognized Kai’s voice. When she stood up, she could feel the woman standing next to her inching away, so as to study her face at a better angle.

“You may still have a chance, if you walk away by yourself now,” Han said, and in a lower voice, he told Kai to go on to the ceremony, as he would wait for the police.

The old woman looked up. “You’ll all see her off in your way. Why can’t I see her off in mine?”

The security patrol explained to Han and Kai that this woman was the mother of the soon-to-be-executed counterrevolutionary. Only then did Kai recognize the defiance in Mrs. Gu’s eyes. She had seen the same expression in Shan’s eyes twelve years ago, when they had been in rival factions of the Red Guards.

“Our way to send your daughter off is not only the most correct way but also the only way permitted by law,” Han said, as he ordered the security patrol to fetch water. Mrs. Gu poked the fire with a tree branch, as if she had not heard him. When the patrol returned with a heavy bucket, Han stepped back and motioned the man to put out the fire. Mrs. Gu did not shield her face from the splashing water. The pile hissed and smoldered, but she poked it again as if she were willing the flame to catch again.

Two policemen, summoned by the other patrol, were now pushing through the crowd and shouting, telling people to move on. Some people left, but many only retreated and formed a bigger circle. “Let’s not make a big fuss out of this,” Kai said to Han, as he strode up to meet the policemen.

“Those who seek punishment will get what they ask for,” Han said.

The patrol greeted the police, and pointed out Han and Kai, but Mrs. Gu paid little attention to the men surrounding her, mumbling something before she wiped tears from the corners of her eyes.

“Why don’t you just let her go?” Kai said to Han, and she quoted an old saying, Favors one does will be returned to him, and pains one causes will be inflicted on him.

Han glanced at Kai, saying that he did not know that she could be superstitious.

“If you don’t want to believe in it for yourself, at least believe in it for your son,” Kai said. The urgency in her voice stopped Han, who looked at her with half-smiling eyes. He said he had never known she would take up the beliefs of the old generation.

“A mother needs all the help possible to ensure a good life for her child,” Kai said. “What if people direct curses at Ming-Ming because of what we do?”

Han shook his head, as if amused by his wife’s logic. He greeted the policemen and told them to escort the old woman home and find someone to clean up the street. “Let’s not make a big fuss this time,” he said, echoing Kai’s words and adding that there was no need to put additional stress on this day. The other men complimented Han for his generosity: More power to him who lets someone off without pursuing an error, the older policeman said, and Han nodded in agreement.

THREE (#ulink_b96f8515-5584-5e5d-90e3-0ecd20bc5f3c)

Mrs. Hua did not see the policemen remove Mrs. Gu from the site of her crime; nor would Mrs. Hua have realized, had she witnessed the scene, that the woman who was half dragged and half carried to the police jeep was Mrs. Gu.

Like Mrs. Hua herself, Mrs. Gu would never become a grandmother. Mrs. Hua was sixty-six, an age when a grandchild or two would provide a better reason to live on than the streets her husband scavenged and she swept, but the streets provided a living, while the dreams about grandchildren did not, and she was aware of the good fortune to be alive, for which she and her husband often reminded themselves to be grateful. Still, the urge to hold a baby sometimes became so strong that she had to pause what she was doing and feel, with held breath, the imagined weight of a small body, warm and soft, in her arms. This gave her the look of a distracted old woman. Once in a while her boss, Shaokang, a man in his fifties who had never married, would threaten to fire her, as if he was angry with her slow response to his requests, but she knew that he only said it for the sake of the other workers in the sanitation department, as he was one of those men who concealed his kindness behind harsh words. He had first offered her a job in his department thirteen years ago, when he had seen Mrs. Hua and her husband in the street, she running a high fever and he begging for a bowl of water from a shop. It was shortly after they had been forced to let the four younger girls be taken away to orphanages in four different counties, a practice believed to be good for the girls to start anew. Mrs. Hua and her husband had walked for three months through four provinces, hoping the road would heal their fresh wound. They had not expected to settle down in Muddy River, but Shaokang told them sternly that the coming winter would certainly kill both of them if they did not accept his offer, and in the end, the will to live on ended their journey.

“The crossroad at Liberation and Yellow River,” said Shaokang, when Mrs. Hua came into the department, a room the size of a warehouse, with a desk in the corner to serve as an office area. She went to the washstand and rinsed the basin. There was little paste left; he had given her much more flour than needed, but she knew he would not question the whereabouts of the leftover flour.

Mrs. Hua went to the closet but most brooms had not yet been returned by the road crew. When all present, the brooms, big ones made out of bamboo branches and small ones made out of straw, would stand up in a line, like a platoon of soldiers, each bearing a number in Shaokang’s neat handwriting and assigned to a specific sweeper. Sometimes Mrs. Hua wondered if in one of Shaokang’s thick notebooks he had a record of all the brooms that had passed through the sanitation department: how much time they had spent in the street and how much they had idled in the closet; how long each broom lasted before its full head went bald. The younger sweepers in the department joked behind Shaokang’s back that he loved the brooms as his own children, but Mrs. Hua saw nothing wrong in that and knew that the joke would come only from young people who understood little of parenthood.

Mrs. Hua picked up the brooms that belonged to her and told Shaokang that the night before she had dreamed of painting red eggs for a grandchild’s birthday. Mrs. Hua spoke to Shaokang only when there was no one around. Sometimes it would be days or weeks before they had a chance to talk, but neither found anything odd in that, their conversations no more than a few words.