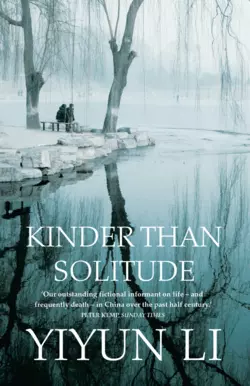

Kinder Than Solitude

Yiyun Li

The new novel from Yiyun Li, author of The Vagrants and the Guardian First Book Award-winning A Thousand Years of Good Prayers.When Moran, Ruyu, and Boyang were young, they were involved in a mysterious ‘accident’ in which a young woman was poisoned. Now grown up, the three friends are separated by this incident, and by time and distance. Boyang stayed in China, while Moran and Ruyu emigrated to the United States. All three remain haunted by what really happened.A breathtaking page-turner, Kinder Than Solitude resonates with provocative observations about human nature and the virtues of loyalty. In mesmerizing prose, and with profound philosophical insight, Yiyun Li unfolds this remarkable story, even as she explores the impact of personality and the past on the shape of a person’s present and future.

Copyright (#ulink_1d561cbb-8db2-56ed-b0fd-4801dd402678)

Fourth Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

www.4thestate.co.uk (http://www.4thestate.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Fourth Estate in 2014

First published in the United States by Random House, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York

Copyright © 2014 by Yiyun Li

Yiyun Li asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

Cover photograph © Giulia Fiori / Getty Images

Designed by Kate Gaughran

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780007329823

Ebook Edition © February 2014 ISBN: 9780007357109

Version: 2015-01-14

To Dapeng, Vincent, and James

You can’t both live and have lived, my dear Christophe.

Romain Rolland, Jean-Christophe

Table of Contents

Cover (#u94703c98-efde-5002-b019-1296795fddf3)

Title Page (#u1c1e3583-16eb-5332-bc46-9d2ae93d73b5)

Copyright (#ua2c4a546-f5ef-5ac3-9bd6-cffec7133f2f)

Dedication (#udb332a38-2d88-583d-a051-a645f53c9a16)

Epigraph (#uf728a705-c467-5628-85ba-2cecf8cdc731)

Chapter 1 (#ud403cc57-ef17-5524-aab5-18a0851c2ee7)

Chapter 2 (#u13137f12-ac2b-5033-abe5-997905a417ed)

Chapter 3 (#u8d000627-b5cf-590d-8889-1dbda53a22db)

Chapter 4 (#u48eeb3b3-32b2-55b8-9c4d-9efddebe02b4)

Chapter 5 (#u581d633b-0fda-59e9-8ade-a604d7dd3302)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Yiyun Li (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1 (#ulink_88b08b5e-ad48-530b-85f9-ab1e2c370349)

Boyang had thought grief would make people less commonplace. The waiting room at the crematory, however, did not differentiate itself from elsewhere: the eagerness to be served first and the suspicion that others had snatched a better deal were reminiscent of the marketplace or stock exchange. A man shouldered him, reaching for multiple copies of the same form. Surely you have only one body to burn, Boyang laughed to himself, and the man glared back, as though personal loss had granted him the right to what he was not owed by the world.

A woman in black rushed in and looked around for a white chrysanthemum that must have been dropped earlier. The clerk, an old man, watched her pin it back onto her collar and smiled at Boyang. “You wonder why they can’t slow down,” he said when Boyang expressed sympathy for what the clerk had to endure. “Day in and day out. These people forget that those who rush to every sweet fruit of life rush to death, too.”

Boyang wondered if the clerk—whom no one wished to meet and, once met, became part of an unwelcome memory—found solace in those words; perhaps he found joy, too, in knowing that those who mistreated him would return in a colder form. The thought made Boyang like him.

When the older man finished his tea, they went over the paperwork for Shaoai’s cremation: her death certificate, the cause of death lung failure after acute pneumonia; the yellowed residence registration card with an official cancellation stamp; her citizen’s ID. The clerk checked the paperwork, including Boyang’s ID, carefully, his pencil making tiny dots under the numbers and dates Boyang had entered. He wondered if the clerk noticed that Shaoai was six years older. “A relative?” the clerk asked when he looked up.

“A friend,” Boyang said, imagining disappointment in the old man’s eyes because Boyang was not a new widower at thirty-seven. He added that Shaoai had been ill for twenty-one years.

“Good that things come to an end.”

There was no option but to agree with the old man’s comfortless words. Boyang was glad that he had dissuaded Aunt, Shaoai’s mother, from coming to the crematory. He would have been unable to guard her from strangers’ goodwill and malevolence alike, and he would have been embarrassed by her grief.

The clerk told Boyang to come back in two hours, and he walked out to the Garden of Perpetual Green. Shaoai would have scoffed at the cypresses and pine trees—symbols of everlasting youth at a crematory. She would have mocked her mother’s sorrow and Boyang’s pensiveness, even her own inglorious end. She, of all people, would have made good use of a life. Her distaste for the timid, the dull, and the ordinary, her unforgiving sharpness: what a waste that edge had rusted, Boyang thought again. The decaying that had dragged on for too long had only turned tragedy into nuisance; death, when it strikes, better completes its annihilating act on the first try.

At the top of a hill, older trees guarded elaborate mausoleums. A few birds—crows and magpies—prattled close enough that Boyang could hit them with a pinecone, but he would need an audience for such a boyish achievement. If Coco were here, she would know how to poke fun at his shot and to look impressed when he showed her the pine nuts inside the cones, though the truth was she had little interest in these things. Coco was twenty-one, yet already she had acquired the incuriosity of one who has lived long enough; her desire—too greedy for her age, or too meager—was for tangible comforts and material possessions.

At the end of a path a pavilion sheltered the bronze bust of a man. Boyang tapped the pillars. They were sturdy enough, though the wood was not the best quality, and the paint had faded and was peeling in places; according to the plaque the pavilion was less than two years old. A bouquet of plastic lilies laid underneath looked more dead than fake. Time, since the economy had taken off, seemed to move at an unreal pace in China, the new becoming old fast, the old vanishing into oblivion. One day he, too, could afford—if he desired it—to be turned into a stone or metal bust, gaining a minor immortality for people to laugh at. With a bit of luck, Coco, or whatever woman replaced Coco, might shed a tear or two in front of his grave—if not for a world without him, then for her misspent youth.

A woman appeared over the rise of the hill, and upon seeing Boyang turned so abruptly he barely glimpsed her face, framed by a black-and-white patterned scarf. He studied her black coat and the designer bag on her arm, and wondered if she was a rich man’s widow, or better, a mistress. For a moment he entertained the thought of catching up with her and exchanging a few words. If they liked each other, they could stop at a village on the drive back to the city and choose a clean countryside restaurant for some rustic flavors: sweet potatoes roasted in a tall metal barrel, chicken stewed with so-called “locally grown, organic” mushrooms, a few sips of strong yam liquor that would make their stories flow more easily and the lunch worth prolonging. Back in the city, they might or might not, depending on their moods, see each other again.

Boyang returned to the counter at the designated time. The clerk informed him that there would be a slight delay, as one family had insisted on checking everything to avoid contamination. Contamination with someone else’s ashes? Boyang asked, and the old man smiled and said that if there was any place where people’s whims would be accommodated, it was this one. Touchy business, Boyang said, and then asked if a woman had come alone to cremate someone.

“A woman?” the clerk said.

Boyang considered describing the woman to the old man, but then decided that a man with a trustworthy face and gentle sense of humor should be dealt with cautiously. He changed the subject and chatted about the new city regulations on real estate. Later, when the clerk asked him if he would like to take a look at Shaoai’s remains before they were ground to ashes—some families requested that, explained the clerk; some asked to pick up the bones themselves for proper closure—Boyang declined the offer.

That everything had come to an end like this was a relief as unconvincing as the pale sun that graced the dashboard as Boyang drove back to the city. The news of the death he had emailed to Moran and Ruyu. Moran, he knew, lived in America, though where Ruyu was he was not certain: America most probably; perhaps Canada, or Australia, or somewhere in Europe. He doubted that the two of them had remained in touch with each other; his own communications with them had never once been acknowledged. On the first of every month, he sent separate emails, informing—reminding—them that Shaoai was alive. He never spoke of the emergencies, lung failure once, and heart failure a few times: to limit the information would spare him the expectation of a reply. Shaoai had always pulled through, clinging to a world that had neither use nor a place for her, and the brief messages he sent had given him a sense of permanency. Loyalty to the past is the foundation of a life one does not, by happenstance or by will, end up living. His persistence had preserved that untouched alternative. Their silence, he believed, proved that to be the case: silence maintained so emphatically could only mean their loyalties matched his, too.

When the doctor confirmed Shaoai’s death, Boyang had felt neither grief nor relief but anger—anger at being proven wrong, at being denied the reunion that he had considered his right: they—he and Moran and Ruyu—were old in his fantasy, ancient even, a man and two women who had nearly lived out their mortal lives, converging one last time at the lake of their youth. Moran and Ruyu would perhaps consider their homecoming a natural, if not triumphant, epitaph. To this celebration he would bring Shaoai, whose presence would turn their decades of accumulation—marriage, children, career, wealth—into a hoarder’s laughable collection. The best life is the life unlived, and Shaoai would be the only one to have a claim to that truth.

Yet their foolishness was his, too, and to laugh at his own absurdity he needed the other two: laughing by oneself is more intolerable than mourning alone. They might not have seen the death notice in their emails—after all, it was only the middle of the month. Boyang knew, by intuition, that the email addresses he had from Moran and Ruyu were not the ones they used every day, as his, used only for communicating with them, was not. That Shaoai had died on him when he had least expected her to, and that neither Moran nor Ruyu had acknowledged his email, made the death unreal, as though he were rehearsing alone for something he needed the other two women—no, all three of them—to be part of; Shaoai, too, had to be present at her own funeral.

A silver Porsche overtook Boyang on the highway, and he wondered if the driver was the woman he had seen in the cemetery. His cell phone vibrated, but he did not unhook it from his belt. He had canceled his appointments for the day, and the call most probably was from Coco. As a rule he kept his whereabouts vague to Coco, so she had to call him, and had to be prepared for last-minute changes. To keep her on uncertain footing gave him the pleasure of being in control. Sugar daddy—she and her friends must have used that imported term behind his back, but once when he, half-drunk, had asked Coco if that was what she took him for, she laughed and said he was too young for that. Sugar brother, she said afterward on the phone with a girlfriend, winking at him, and later he’d thanked her for her generosity.

It took him a few passes to find a parking spot at the apartment complex, built long before cars were a part of the lives of its occupants. A man who was cleaning the windshield of a small car—made in China from the look of it—cast an unfriendly look at Boyang as he exited his car. Would the man, Boyang wondered while locking eyes with the stranger sternly, leave a scratch on his BMW, or at least kick its tire or bumper, when he was out of sight? Such conjecture about other people no doubt reflected his own ignobleness, but a man must not let his imagination be outwitted by the world. Boyang took pride in his contempt for other people and himself alike. This world, like many people in it, inevitably treats a man better when he has little kindness to spare for it.

Before he unlocked the apartment door with his copy of the key, Aunt opened it from inside. She must have been crying, her eyelids red and swollen, but she acted busy, almost cheerful, brewing tea that Boyang had said he did not need, pushing a plate of pistachios at him, and asking about the health of his parents.

Boyang wished he had never known this one-bedroom unit, which, already shabby when Aunt and Uncle had moved into it with Shaoai, had not changed much in the past twenty years. The furniture was old, from the ’60s and ’70s, cheap wooden tables and chairs and iron bed frames that had long lost their original shine. The only addition was a used metal walker, bought inexpensively from the hospital where Aunt used to work as a nurse before retiring. Boyang had helped Uncle to saw off its wheels, readjust its height, and then secure it to a wall. Three times a day Shaoai had been helped onto it and practiced standing by herself so that her muscles retained some strength.

The old sheets wrapped around the armrests had worn out over the years, the sky-blue paint badly chipped and exposing the dirty metal beneath. Never, Boyang thought, would he again have to coax Shaoai to practice standing with a piece of candy, yet was this world without her a better place for him? Like a river taking a detour, time that had passed elsewhere had left the apartment and its occupants behind, their lives and deaths fossils of an inconsequential past. Boyang’s own parents had purchased four properties in the last decade, each one bigger than the previous one; their current home was a two-story townhouse they never tired of inviting friends to, for viewings of their marble bathtub and crystal chandelier imported from Italy and their shiny appliances from Germany. Boyang had overseen the remodeling of all four places, and he managed the three they rented out. He himself had three apartments in Beijing; the first, purchased for his marriage, he had bestowed upon his ex-wife as a punishing gesture of largesse when the man she had betrayed Boyang for had not divorced his own wife as he had promised.

A black-and-white photograph of Shaoai, enlarged and set in a black frame, was hung up next to a picture of Uncle, who had died five years earlier from liver cancer. A plate of fresh fruit was placed in front of the pictures, oranges quartered, melons sliced, apples and pears, intact, looking waxy and unreal. These Aunt timidly showed Boyang, as though she had to prove that she had just the right amount of grief—too much would make her a burden; too little would suggest negligence. “Did everything go all right?” she asked when she ran out of the topics she must have prepared before his return.

The image of Aunt’s checking the clock every few minutes and wondering where her daughter’s body was disturbed Boyang. He regretted that he had pressed Aunt not to go to the crematory, but at once he chased that thought away. “Everything went well,” he said. “Smoothly.”

“I wouldn’t know what to do without you,” Aunt said.

Boyang unwrapped the urn from the white silk bag and placed it next to the plate of fruits. He avoided looking closely at Shaoai in the photo, which must have been taken during her college years. Over the past two decades, she had doubled in size, and her face had lost the cleanly defined jawline. To be filled with soft flesh like that, and to vanish in a furnace … Boyang shuddered. The body, in its absence, took up more space than it had when alive. Abruptly he went over to the walker by the wall and assessed the possibility of dismantling it.

“But we’ll keep it, shall we?” Aunt said. “It could come in handy someday for me.”

Unwilling to let Aunt steer the conversation toward the future, Boyang nodded and said he would have to leave soon; he was to meet a business partner.

Of course, Aunt said, she would not keep him.

“I’ve emailed Ruyu and Moran,” he said at the door. It was cowardly to bring up their names, but he was afraid that if he did not unburden himself, he would be spending another night drinking more than was good for his health, singing intentionally off-key at the karaoke bar, and telling lewd jokes too loudly.

Aunt paused as though she had not heard him right, so he said again that the news had been sent to Moran and Ruyu. Aunt nodded and said it was right of him to tell them, though he knew she was lying.

“I thought you might like me to,” Boyang said. It was cruel to take advantage of the old woman who was not in a position to protest, but he wanted to talk with someone about Moran and Ruyu, to hear their names mentioned by another voice.

“Moran is a good girl,” Aunt said, reaching up to pat his shoulder. “I’ve always been sorry that you didn’t marry her.”

Even the most innocent person, when cornered, is capable of a heartless crime. Boyang was amazed at how effortless it was for Aunt to inflict such fatal pain. It was unlike her to say anything about his marriage. Between them they had shared only Shaoai. He had told Aunt about his divorce, but he had not needed to remind her, as he had had to remind his parents, not to discuss it. And to speak of Moran as a better candidate for his marriage while intentionally leaving out the other name—Boyang felt an urge to punish someone, though he only shook his head. “Marriage or no,” he said, “I need to run now.”

“And to think we haven’t heard from Moran for so long,” Aunt persisted.

Boyang ignored the comment, and said he would come back later that week. When he had asked Aunt about the burial of Shaoai’s cremains, she had replied that she was not ready. He suspected, perhaps unfairly, that Aunt was holding on to the urn of ashes because that was the last thing binding him to this apartment. He and Aunt were not related by blood.

When Boyang got back into his car, he saw that both his mother and Coco had called. He dialed his mother’s number and, after the call, sent a text to Coco saying he would be busy for the rest of the day. Coco and his mother were the two chief competitors for his attention these days. He had not deemed it worthwhile to introduce the two—one was too transient in his life, and the other, too permanent.

Going to his parents’ place after Aunt’s was a comfort. Remodeled as though for an advertisement in a consumer magazine, their home provided a perfect veil behind which the world of unpleasantness receded. Here more than elsewhere Boyang understood the significance of investing in trivialities: beautiful objects, like expensive drinks and entertaining acquaintances, demand that one think little and feel nothing beyond one’s immediate surroundings.

They had taken some friends out for dinner the night before, Boyang’s mother explained. They had too many leftovers, so she thought Boyang might as well come and get rid of the food for them. He laughed, saying he did not know he was their compost bin. His parents had become particular in their eating habits, obsessing over the health benefits, or lack thereof, of everything entering their bodies. He could see that they would order an excessive amount of food for their friends yet touch little themselves.

The topics at dinner were his sister’s American-born twins, the real estate prices in Beijing and in a coastal city where his parents were pondering purchasing a waterfront condo, and the inefficiency of their new housekeeper. Only when his mother had cleaned away the dishes did she ask, as though grasping a passing thought, if Boyang had heard of Shaoai’s death. By then, his father had gone into his study.

That he had kept in touch with Shaoai’s parents and had acted as caretaker when illnesses and deaths had beset their family—this Boyang had seen no reason to share with his parents. If they had suspected any connection, they had preferred not to know. The key to success, in his parents’ opinion, was the capacity to selectively live one’s life, to forget what one ought not to remember, to untangle oneself from lesser and irrelevant others, and to recognize the unnecessariness of human emotions. Fame and material gain are secondary though unsurprising, if one is able to choose the portion of one’s life to live with impersonal wisdom. For this belief they had, as an example, Boyang’s sister, who was a prominent physicist in America.

“So I heard,” Boyang said. Aunt would not have kept the death from the old neighbors, and it did not surprise him that one of them—or perhaps more than one—had called his parents. If there were any pleasure in delivering the news of death it would be that call, castigation barely masked by courteousness.

His mother returned from the kitchen with two cups of tea and passed one to him. He cringed at her nudging the conversation beyond the comfortable repertoire of their usual topics. He showed up whenever she summoned him; the best way to stay distanced, he believed, was to satisfy her every need.

“What do you think, then?” his mother said.

“Think of what?”

“The whole thing,” she said. “One must acknowledge the waste, no?”

“What waste?”

“Shaoai’s life, obviously,” his mother said, adjusting a single calla lily in a crystal vase on the dinner table. “But even if you take her out of the equation, others’ lives have been affected.”

What others, Boyang wanted to say to his mother, would be worth a moment of her thought? The chemical found in Shaoai’s blood had been taken from his mother’s laboratory; whether it had been an attempted murder, an unsuccessful suicide, or a freak accident had never been determined. His family did not talk about the case, but Boyang knew that his mother had never let go of her grudge.

“Do you mean your career went to waste?” Boyang asked. After the incident, the university had taken disciplinary action against his mother for her mismanagement of chemicals. It would have been an unpleasant incident, a small glitch in her otherwise stellar academic career, but she insisted on disputing the charge: every laboratory in the department was run according to outdated regulations, with chemicals available to all graduate students. It was a misfortune that a life had been damaged, she admitted; she was willing to be punished for allowing three teenage children to be in her lab unsupervised—a mismanagement of human beings rather than chemicals.

“If you want to look at my career, sure—that’s gone to waste for no reason.”

“But things have turned out all right for you,” Boyang said. “Better, you have to admit.” His mother had left the university and joined a pharmaceutical company, later purchased by an American company. With her flawless English, which she’d learned at a Catholic school, and several patents to her name, she earned an income three times what she would have made as a professor.

“But did I say I was speaking of myself?” she said. “Your assumption that I have only myself to think of is only a hypothesis, not a proven fact.”

“I don’t see anyone else worthy of your thought.”

“Not even you?”

“What do you mean?” The weakest comeback, Boyang thought: people only ask a question like that because they already know the answer.

“You don’t feel your life has been affected by Shaoai’s poisoning?”

What answer did she want to hear? “You get used to something like that,” he said. On second thought, he added, “No, I wouldn’t say her case has affected me in any substantial way.”

“Who wanted her to die?”

“Excuse me?”

“You heard me right. Who wanted to kill her back then? She didn’t seem like someone who would commit suicide, though certainly one of your little girlfriends, I can’t remember which one, hinted at that.”

In rehearsing scenarios of Shaoai’s death Boyang had never included his mother—but when does any parent hold a position in a child’s fantasy? Still, that his mother had paid attention, and that he had underestimated her awareness of the case, annoyed him. “I’m sure you understand that if, in all honesty, you tell me that you were the one who poisoned her, I wouldn’t say or do anything,” she said. “This conversation is purely for my curiosity.”

They were abiding by the same code, of maintaining the coexistence between two strangers, an intimacy—if their arrangement could be called that—cultivated with disciplined indifference. He rather liked his mother this way, and knew that in a sense he had never been her child; nor would she, in growing old, allow herself to become his charge. “I didn’t poison her,” he said. “I’m sorry.”

“Why sorry?”

“You’d be much happier to have an answer. I’d be happier, too, if I could tell you for sure who poisoned her.”

“Well then, there are only two other possibilities. So, do you think it was Moran or Ruyu?”

He had asked himself the question over the years. He looked at his mother with a smile, careful that his face not betray him. “What do you think?”

“I didn’t know either of them.”

“There was no reason for you to know them,” Boyang said. “Or, for that matter, anyone.”

His mother, as he knew, was not the kind to dwell upon sarcasm. “I never really met Ruyu,” she said. “Moran of course I saw around, but I don’t remember her well. I don’t recall her being brilliant, am I right?”

“I doubt there is anyone brilliant enough for you.”

“Your sister is,” Boyang’s mother said. “But don’t distract me. You used to know them both well, so you must have an idea.”

“I don’t,” Boyang said.

His mother looked at him, rearranging, he imagined, his and the other people’s positions in her head as she would do with chemical molecules. He remembered taking his parents to America to celebrate their fortieth wedding anniversary. At the airport in San Francisco, they’d seen an exhibition of duck decoys. Despite the twelve-hour flight, his mother had studied each of the wooden ducks. The colors and shapes of the different decoy products fascinated her, and she read the old 1920s posters advertising twenty-cent duck decoys, using her knowledge of inflation rates over the years to calculate how much each duck would cost today. Always so curious, Boyang thought, so impersonally curious.

“Did you ever ask them?” she said now.

“Whether one of them tried to murder someone?” Boyang said. “No.”

“Why not?”

“I think you’re overestimating your son’s ability.”

“But do you not want to know? Why not ask them?”

“When? Back then, or now?”

“Why not ask now? They may be honest with you now that Shaoai is dead.”

For one thing, Boyang thought, neither Moran nor Ruyu would answer his email. “If you’re not overestimating my ability, you are certainly overestimating people’s desire for honesty,” he said. “But has it occurred to you it might’ve only been an accident? Would that be too dull for you?”

His mother looked into her tea. “If I put too many tea leaves in the teapot, that could be considered a mistake. No one puts poison into another person’s teacup by accident. Or do you mean that Moran or Ruyu was the real target, and poor Shaoai happened to take the wrong tea? To think, it could’ve been you!”

“My drinking the poison by accident?”

“No. What I’m asking is: what do you think of the possibility of someone trying to murder you?”

The single calla lily—his mother’s favorite flower—looked menacing, unreal with its flawless curve. She blew lightly over her tea, not looking at him, though he knew that was part of her scrutiny. Was she distorting the past to humor herself, or was she revealing her doubt—or was the line between distorting and revealing so fine that one could not happen without the other? For all he knew, he had lived in her selective unawareness, but perhaps this was only an illusion. One ought not to have the last word about one’s own mother.

He admitted that the thought had never occurred to him. “It’s a possibility, you know,” she said.

“But why would anyone have wanted to kill me?”

“Why would anyone want to kill anyone?” she said, and right away Boyang knew that he had spoken too carelessly. “If someone steals poison from a lab, that person intends to do harm to another person or to herself. For all I know, the harm was already done the moment that chemical was stolen. And I’m not asking you why. Why anyone does anything is beyond my understanding or interest. All I would like to know is who was trying to kill who, but unfortunately you don’t have an answer. And sadly, you don’t seem to share my curiosity.”

2 (#ulink_5855b294-67de-5c1a-9665-451171d4cd76)

When the train pulled into Beijing’s arched station on August 1, 1989, Ruyu, adjusting her eyes from the glare of the afternoon to the shadowed grayness of the station, did not yet know that one’s preparation for departure should begin long before arrival. There were many things that she, at fifteen, had still to learn. To seek answers to one’s questions is to know the world. Guileless in childhood, private as one grows older, and, for those who insist on the certainty of adulthood, ignored when they become unanswerable, these questions form the context of one’s being. For Ruyu, however, an answer that excluded all questions had already been provided.

The passengers moved to both ends of the car. Ruyu remained seated and looked through the grimy window. On the platform, people pushed one another out of the way with their arms, as well as—more effectively—their bags and suitcases. Someone—though Ruyu did not know who, nor did she feel compelled to be curious—would be waiting for her on the platform. She took a pair of barrettes from her school satchel and clipped them in her hair. This was how her grandaunts had described her to her hosts in a letter they’d sent a week before her journey: a white shirt, a black skirt, and two blue barrettes in the shape of butterflies, a brown willow trunk, a 120-bass accordion in a black leather case, a school satchel, and a canteen.

The last two passengers, a pair of middle-aged sisters-in-law, asked her if she needed help. Ruyu thanked them and said no, she was fine. During the nine-hour journey, the two women had studied Ruyu with unconcealed curiosity; that she had only taken sips of water, that she had not left her seat to use the washroom, that she had not let go of her clasp of her school satchel—these things had not escaped their eyes. They had offered Ruyu a peach and a pack of soda crackers and later a bottle of orange juice purchased through the window at a station, all of which Ruyu had declined politely. They had between themselves approved of her manner, though that had not stopped them from feeling offended. The girl was small-built, and appeared too young for a solo journey in the opinion of the women and other fellow travelers; but when they had questioned her, she had replied with restraint, revealing little of the nature of her trip.

When the aisle was cleared, Ruyu heaved the accordion case off the luggage rack. Her school satchel, made of sturdy canvas, she had had since the first grade, and its color had long faded from grass green to a pale, yellowish white. Inside it, her grandaunts had sewn a small cloth bag, in which were twenty brand-new ten-yuan bills, a large amount of money for a young girl to carry. With great care, Ruyu pulled the trunk from under her seat—it was the smallest of a set of three willow trunks that her grandaunts owned, purchased, they had told her, in 1947 in the best department store in Shanghai, and they had asked her to please be gentle with it.

Shaoai recognized Ruyu the moment she stumbled onto the platform. Who would have thought, besides those two old ladies, of stuffing a girl into such an ancient-looking outfit and then, on top of that, making her carry an outdated, childish school satchel and a water canteen? “You look younger than I expected,” Shaoai said when she approached Ruyu, though it was a lie. In the black-and-white photo the two grandaunts had sent, Ruyu, despite the woolen, smock-like dress that was too big for her, looked like an ordinary schoolgirl, her eyes candidly raised to the camera; they were the eyes of a child who did not yet know and was not concerned with her place in the world. The face in front of Shaoai now showed a frosty inviolability a girl Ruyu’s age should not have possessed. Shaoai felt slightly annoyed, as though the train had brought the wrong person.

“Sister Shaoai?” Ruyu said, recognizing the older girl from the family picture sent to her grandaunts: short hair, angular face, thin lips adding an impatient touchiness to the face.

From the pocket of her shorts Shaoai produced the photo Ruyu’s grandaunts had mailed along with their letter. “So that you know you’re not being met by the wrong person,” Shaoai said, and then stuffed the photo back into her pocket.

Ruyu recognized the photo, taken when she had turned fifteen two months earlier. Every year on her birthday—though whether it was her real birthday or only an approximation of it she had wondered at times without asking—her grandaunts took her to the photographer’s for a black-and-white portrait. The final prints were saved in an album, each fit into four silver corners glued on a new page, with the year written on the bottom of the page. Over the years the photographer, who had begun as an apprentice but was no longer a young man, had never had Ruyu change her position, so in all the birthday portraits she sat straight, with her hands folded on her lap. What Shaoai had must be an extra print, as Ruyu’s grandaunts were not the kind of people who would disturb a perfectly ordered album and leave a blank among four corners. Still, the thought that a stranger had kept something of her unsettled Ruyu. She felt the dampness of her palms and wiped them on the back of her black cotton skirt.

“You should get some cooler clothes for the summer,” Shaoai said, looking at Ruyu’s long skirt.

In Shaoai’s disapproving look Ruyu saw the same presumptuousness she had detected in the middle-aged women on the train. So the older girl was no different from others—quick to put themselves in a place where they could advise Ruyu about how to live. What separated Ruyu from them, they did not know, was that she had been chosen. What she knew would never be revealed to them: she could see, and see through, them in a way they could not see her, or themselves.

Shaoai was twenty-two, the only daughter of Uncle and Aunt, who were, in some convoluted way Ruyu’s grandaunts had not explained, relatives of the two old women. “Honest people,” her grandaunts had pronounced of the family who had promised to take her in for a year—or, if things worked out, for the next three years, until Ruyu went to college. There were a couple of other families in Beijing, also of remote connections, whom her grandaunts had considered, but both households included boys Ruyu’s age or not much older. In the end, Shaoai and her parents had been chosen to avoid possible inconvenience.

“Do you need a minute to catch your breath?” Shaoai asked, and picked up the trunk and the accordion before Ruyu could reply. She offered to carry one of the items herself, and Shaoai only jerked her chin toward the exit and said she had helpers waiting.

Ruyu was not prepared for the noises and the heat of the city outside the station. The late afternoon sun was a white disc behind the smog, and over loudspeakers a man was reading, in a stern voice, the names and descriptions of fugitives wanted for sabotaging the government earlier that summer. Travelers for whom Beijing was only a connecting stop occupied the available shade under the billboards, and the less lucky ones lay under layers of newspapers. Five women with cardboard signs swarmed toward Shaoai and, with competing voices at high volume, recommended their hostels and shuttle services. Shaoai deftly swung the trunk and the accordion case through the crowd, while Ruyu, who’d hesitated a moment too long, was surrounded by other hawkers. A middle-aged woman in a sleeveless smock grabbed Ruyu’s elbow and dragged her away from the other vendors. Ruyu tried to wiggle her arm free and explain that she was only visiting relatives, but her feeble protest was muffled by the thick fog of noise. In her provincial hometown, rarely would a stranger or an acquaintance come this close to her; when she was younger, her grandaunts’ upright posture and grave expression had protected her from the invasion of the world; later, even when she was not being escorted by them, people would leave her alone in the street or in the marketplace, her grandaunts’ severity recognized and respected in her own unsmiling bearing.

It took Shaoai no time, when she returned, to free Ruyu from the hawkers. Where is my accordion, Ruyu asked when she noticed Shaoai’s empty hands. The accusation stopped Shaoai. With my helpers, of course, she said; why, you think I would abandon your valuable luggage just to rescue someone who has her own legs to run?

Ruyu had never been in a situation where she had to run away; her grandaunts—and in recent years she was aware that she, too—had the ability to make people recede from their paths. As an infant she had been left on the doorstep of a pair of unmarried Catholic sisters, and she was raised by the two women who were not related to her by blood. Like two prophets, her grandaunts had laid out the map of her life for her, that her journey would take her from their small apartment in the provincial city to Beijing and later abroad, where she would find her real and only home in the Church. Outside of the one-bedroom apartment she shared with them, neighbors and schoolteachers and classmates were unnecessarily inquisitive about her life, as though the porridge she ate at breakfast or the mittens dangling from a string around her neck offered clues to a puzzle beyond their understanding. Ruyu had learned to answer their questions with cold etiquette. Still, she despised their ignorance: their lives were to be lived in the dust; hers, with the completeness of purity.

Shaoai’s helpers, waiting in the shade of a building by the roadside, were a boy and a girl. Shaoai introduced them: Boyang, the stout boy with tanned skin who was roping the accordion case to the back rack of his bicycle, had white flashing teeth when he smiled; Moran, the skinny, long-legged girl sitting astride her bicycle, had already secured the willow trunk behind her. They were neighbors, Shaoai said; both were a year older than Ruyu, but she would be in the same grade with them in her new school. Boyang and Moran glanced at the accordion case when school was mentioned, so they must have been informed of the plan. Ruyu did not have legal residence in Beijing; when her grandaunts had first proposed her stay, Uncle and Aunt had written back, explaining that they would absolutely love to help out with Ruyu’s education but that most high schools would not admit a student who did not have city residency. Ruyu is a good musician, her grandaunts replied, and enclosed a copy of the certificate of her passing grade 8 on her accordion. How Uncle and Aunt had convinced the high school—Shaoai’s alma mater—to admit Ruyu on account of her musical talents, Ruyu did not know; her grandaunts, when they had received the letter requiring that the accordion and the original copy of the grade 8 certificate accompany Ruyu to Beijing, had not shown surprise.

That night, Ruyu lay in the bed that she was to share with Shaoai and thought about living in a world where her grandaunts’ presence was not sensed and respected, and for the first time she felt she was becoming the orphan people had taken her to be. Already Beijing made her feel small, but worse than that was people’s indifference to her smallness. On the bus ride from the train station to her new home, a man in a short-sleeved shirt had stood close to Ruyu, and the moment the bus had begun to move, he seemed to press much of his weight on her. She inched away from him, but his weight followed her, imperceptible to the other passengers, for when Ruyu looked at the two middle-aged women sitting in a double seat in front of her, hoping for some help, the two women—strangers, judging from how they did not talk or smile at each other—turned their faces away and looked at the shops out the window. The predicament would have lasted longer if it hadn’t been for Shaoai, who, after purchasing their tickets from the conductor, had pushed through the crowd and, as though reaching for the back of a seat to steady herself, squeezed an arm between the man and Ruyu. Nothing had been said, but perhaps Shaoai had elbowed the man or given him a stern look, or it was simply Shaoai’s presence that had made the man retreat. For the rest of the bus ride Shaoai stood close, a steely presence between Ruyu and the rest of the world. Neither girl spoke, and when it was time for them to get off, Shaoai tapped Ruyu on the shoulder and signaled her to follow while Shaoai pushed through the bodies. The short-sleeved man, Ruyu noticed, fixed his eyes on her face as she moved toward the exit. Even though there were quite a few people between them, Ruyu felt her face burn.

On the sidewalk, Shaoai asked Ruyu if she was too dumb to protect herself. Rarely did Ruyu face an angry person at a close distance; both her grandaunts had equable temperaments, believing any kind of emotional excitability a hurdle to one’s personal improvement. She sighed and turned her eyes away so as not to embarrass Shaoai.

For a split second, Shaoai regretted her eruption—after all, Ruyu was a young girl, a provincial, an orphan raised by eccentric old ladies. Shaoai would have willingly softened, and even apologized, if Ruyu had understood the source of her anger, but the younger girl did not make a gesture either to mollify Shaoai or to defend herself. In Ruyu’s silence, Shaoai sensed a contemptuous extrication. “Haven’t your grandaunts taught you anything useful?” Shaoai said, angrier now, both at Ruyu’s unresponsiveness and at her own temper.

Nothing separated Ruyu more thoroughly from the world than its malignance toward her grandaunts. To ward off people’s criticism of her grandaunts was more than to justify how they had raised her: to defend them was to defend God, who had chosen her to be left at their door. “My grandaunts have taught me more than you could imagine,” Ruyu said. “If you don’t like my coming to stay with your family, I understand. I’m not here for you to like, and my grandaunts are not for you to approve or disapprove of.”

Shaoai had stared at Ruyu for a long moment, and then shrugged as though she no longer was in the mood to argue with Ruyu. When they had reached Shaoai’s home the episode seemed to have been put behind them.

Please—Ruyu folded her hands on her chest—please show me that a big city is nothing compared to you. The bamboo mattress under her was no longer cooling her off, but she refrained from moving to a new spot and stayed on the edge of the bed Shaoai had pointed to as her side. The only window in the room, a small rectangular one high on the wall, admitted little night air, and inside the mosquito netting Ruyu felt her pajamas sticking to her body. A television set, its volume low, was blinking in the living room, though Ruyu doubted that Uncle and Aunt were watching it. For a while they had been talking in whispers, and Ruyu wondered if they had been talking about her or her grandaunts. Please, she said again in her mind, please give me the wisdom to live among strangers until I leave them behind.

Ruyu’s grandaunts had not taught her to pray. Her upbringing had not been a strictly religious one, though her grandaunts had done what they could to give her an education that they had deemed necessary to prepare her for her future reunion with the Church. They themselves had not attended any services since 1957, when the Church was reformed by the Communist Party into the Chinese Patriotic Catholic Association; nor did they keep any concrete evidence of their previous spiritual lives. Still, from a young age, Ruyu had understood that what set her apart from other children was not the absence of her parents but the presence of God in her life, which made parents and siblings and playmates and even her grandaunts extraneous. She had begun to talk to him before she entered elementary school. “Our Father in Heaven,” she’d heard her grandaunts say when she had been a small girl, and it was with a conversation with him that Ruyu would end each day, talking to him as a child would talk to an imaginary friend or to herself, a presence at once abstract and solidly comforting. But he was neither a friend nor a part of herself; he belonged to her as much as he belonged to her grandaunts. None of the people she had met so far in Beijing, Ruyu knew, shared with her the secret of his presence: not Uncle and Aunt, who had told her that she was one of the family now and had asked her not to feel shy about making requests; not the neighbors, the five other families who had all come out to the courtyard upon her arrival, talking to her as though they had known her forever, a man teasing her about her accordion, which seemed too big for her narrow shoulders, a woman disapproving of her outfit because it would give her a heat rash in this humid weather; not the boy Boyang or the girl Moran, both of whom were quiet in front of their seniors, but who, Ruyu knew from the looks the two exchanged, had more to say to each other; and not Shaoai, who, queenly in her impatience toward the fuss the neighbors made over the newcomer, had left the courtyard before they had finished welcoming Ruyu.

Please make the time I have to spend with these strangers go fast so that I can come to you soon. She was about to finish the conversation, as usual, with an apology—always she asked too much of him while offering nothing in return—when the front door opened and then banged shut; the metal bell she had seen hanging from the door frame jingled and was hushed right away by someone’s hand. Aunt said something, and then Shaoai, who must have been the one who’d come into the house, replied with some sort of retort, though both talked in low voices, and Ruyu could not hear their exchanges. She looked through the mosquito netting at the curtain that separated the bedroom from the living room—a white floral print on blue cotton fabric—and at the light from the living room creeping into the bedroom from underneath the curtain.

The house, more than a hundred years old, had been built for traditional family life, the center of the house being the living room, the entries between the living room and the bedrooms open, with no doors. The smallest bedroom, no larger than a cubicle and located to the right of the main entrance, was the entire world occupied by Grandpa—Uncle’s father, who had been bedridden for the last five years after a series of strokes. Earlier in the evening, when Aunt had shown Ruyu around the house, she’d raised the curtain quickly for Ruyu to catch a glimpse of the old man lying under a thin, gray blanket, the only life left in his gaunt face a pair of dull eyes that rolled toward Ruyu. He had said something incomprehensible, and Aunt had replied in a loud yet not unkind voice that there was nothing for him to worry about. They were sorry they could not offer Ruyu her own bedroom, Aunt said, and then pointed to the curtain that hid Grandpa and added in a low voice: “Who knows. This room could be vacant any day.”

The bedroom Ruyu was to share with Shaoai was the biggest in the house and used to belong to Uncle and Aunt. Aunt apologized for not having had time to make many changes, besides installing a new student’s desk in the corner of the room. The other bedroom—Shaoai’s old bedroom—was not large enough to accommodate the desk, so it wouldn’t do, Aunt explained, since Ruyu needed her own quiet corner to study. Ruyu mumbled something halfway between an apology and an acknowledgment, though Aunt, flicking dust off the shade of the desk lamp—new also, bought on sale with the desk, she said—did not seem to hear. Ruyu wondered if her grandaunts had considered how their plan for her would change other people’s lives; if they had known anything, they had not told her, and it perplexed her that a small person like herself could cause so much inconvenience. At dinnertime, Shaoai had scoffed when Aunt reminded her to show Ruyu how to clip the mosquito netting, saying that even a child could do that, to which Aunt had replied in an appeasing tone that she just wanted to make sure Ruyu felt informed about her new home. Uncle, reticent, with a sad smile on his face, had come to the dinner table in a threadbare undershirt, but had hurried back to the bedroom when Aunt had frowned at him, and returned in a neatly buttoned shirt. From the expectant looks on Aunt’s and Uncle’s faces, Ruyu knew that the dinner had been prepared for her with extra effort, and, later in the evening, when she fetched water from the wooden bucket next to the kitchen for her washstand, she overheard Uncle comforting Aunt, telling her that perhaps the girl was simply tired from her journey, and Aunt replying that she hoped Ruyu’s appetite would return, as it’s certainly not healthy for a person her age to eat only morsels like a chickadee.

Someone walked close to the bedroom, a shadow looming on the curtain. Ruyu closed her eyes when she recognized Shaoai’s profile. Aunt whispered something to which Shaoai did not reply before entering the bedroom. She stopped in the semidarkness and then turned on the light, a bare bulb hanging low from the ceiling. Ruyu closed her eyes tighter and listened to Shaoai fumble around. After a moment, an electric fan turned on, its droning the only sound in the quietness of the night. The breeze instantly lifted the mosquito netting, and with an exaggerated sigh Shaoai tucked the bottom of the netting underneath the mattress. “You have to be at least a little smarter than the mosquitoes,” she said.

Ruyu did not know if she should apologize and then decided not to open her eyes.

“You shouldn’t wrap yourself up in the blanket,” Shaoai said. “It’s hot.”

After a pause, Ruyu replied that she was all right, and Shaoai did not pursue the topic. She turned off the light and changed in the darkness. When she climbed into the bed from her side and readjusted the mosquito netting, Ruyu regretted that she had not prepared herself by turning away so that her back faced the center of the bed. It was too late now, so she tried to hold her body still and breathe quietly. Please, she said, sensing that she was on Shaoai’s mind, please mask me with your love so they can’t feel my existence.

Later, when Shaoai was asleep, Ruyu opened her eyes and looked at the mosquito netting above her, gray and formless, and listened to the fan swirling. She had been off the train for a few hours now, but still her body could feel the motion, as though it had retained—and continued living—the memory of traveling. There was much to get used to in her new life, a public outhouse at the end of the alleyway Moran had shown her earlier; an outdoor spigot in the middle of the courtyard, where Ruyu had seen Boyang and a few other young men from the quadrangle gather after sunset, topless, splashing cold water onto their upper bodies and taking turns putting their heads under the tap to cool down; a bed shared with a stranger; meals supervised by anxious Aunt. For the first time that day, Ruyu felt homesick for her bed tucked behind an old muslin screen in the foyer of her grandaunts’ one-room apartment.

3 (#ulink_e766f489-f796-5e29-9fec-5cfa8bc3aa6c)

Celia’s message on Ruyu’s voice mail sounded panicked, as though Celia had been caught in a tornado, but Ruyu found little surprise in the emergency. That evening it was Celia’s turn to host ladies’ night. These monthly get-togethers had started as a book club, but, as more books went unfinished and undiscussed, other activities had been introduced—wine tasting, tea tasting, a question-and-answer session with the president of a local real estate agency when the market turned downward, a holiday workshop on homemade soaps and candles. Celia, one of the three founders of the book club, had nicknamed it Buckingham Ladies’ Society, though she used the name only with Ruyu, thinking it might offend people who did not belong to the club, as well as some who did. Not everyone in the book club lived on Buckingham Road. A few of them lived on streets with less prominent names: Kent Road, Bristol Lane, Charing Cross Lane, and Norfolk Way. Properties on those streets were of course more than decent, and children from those houses went to the same school as hers did, but Celia, living on Buckingham, could not help but take pleasure in the subtle difference between her street and the others.

Ruyu wondered if the florist had misinterpreted the color theme Celia had requested, or if the caterer—a new one she was trying out, upon a friend’s recommendation—had failed to meet her expectations. In either case, Ruyu’s presence was urgently needed—could she please come early, Celia had said in the voice mail, pretty please?—not, of course, to right any wrong but to bear witness to Celia’s personal tornado. Being let down was Celia’s fate; life never failed to bestow upon her pain and disappointment she had to suffer on everyone’s behalf, so that the world could go on being a good place, free from real calamities. Celia’s martyrdom, in most people’s—less than kind—opinion, amounted to nothing but a dramatic self-centeredness, but Ruyu, one of the very few who took Celia’s sacrifice seriously, understood the source of her suffering: Celia, though lapsed, had been brought up by Catholic parents.

Edwin and the boys were off to dinner and then to a Warriors game, Celia told Ruyu when she arrived at the Moorlands’. A robin had flown into a window that morning, knocking itself out and setting off the alarm, Celia said, and thank goodness the window was not broken and Luis—the gardener—was here to take care of the poor bird. The caterer was seventeen minutes late, so wasn’t it wise of her to have changed the delivery time to half an hour earlier? In the middle of recounting an exchange between the deliveryman and herself, Celia stopped abruptly. “Ruby,” she said. “Ruby.”

“Yes,” Ruyu said. “I’m listening.”

Celia came and sat down with Ruyu in the breakfast nook. The table and the benches were made of wood reclaimed from an old Kensington barn where Celia’s grandmother, she liked to tell her visitors, used to go for riding lessons. “You look distracted,” Celia said, pushing a glass of water toward Ruyu.

The woman Celia thought of as Ruby should have unwavering attention as an audience. Ruyu thanked Celia for the water and said that nothing was really distracting her. To Celia’s circle of friends—many of whom would arrive soon—Ruyu was, depending on what was needed, a woman of many possibilities: a Mandarin tutor, a reliable house- and pet-sitter, a last-minute babysitter, a part-time cashier at a confection boutique, an occasional party helper. But her loyalty, first and foremost, belonged to Celia, for it was she who had found Ruyu these many opportunities, including the position at La Dolce Vita, a third-generation family business owned by a high school friend of Celia’s.

Celia did not often notice anything beyond her immediate preoccupation, but sometimes, distraught, she was able to perceive other people’s moods. In those moments she adamantly required an explanation, as though her tenacious urge to know someone else’s suffering offered a way out of her own. Ruyu wondered whether she looked disturbed and wished she had touched up her face before entering the house.

“You are not yourself today,” Celia said. “Don’t tell me you had a tough day. The day is already bad enough for me.”

“Here’s what I have done today: I was in the shop in the morning; I stopped at the dry cleaners; I fed Karen’s cats; I took a walk,” Ruyu said. “Now, tell me how hard my day could be.”

Celia sighed and said that of course Ruyu was right. “You don’t know how I envy you.”

Ruyu had been told this often, and once in a while she almost believed Celia to be sincere. “You sounded dreadful in your voice mail,” Ruyu said. “What happened?”

What happened, Celia said, was pure outrage. She went away and came back with a pair of white T-shirts. Earlier that afternoon she had attended a meeting for the fundraising of a major art festival in San Francisco, and on the committee was a writer whose teen detective mysteries were recent bestsellers. “You’d think it’s not too much to ask a writer to sign a couple of shirts for his fans,” Celia said. “You’d think any decent man would have more respect than this.” She dropped the T-shirts on Ruyu’s lap in disgust, and Ruyu spread them on the table. In black permanent marker and block letters, the writer had written, “To Jake, a future orphan” and “To Lucas, a future orphan,” followed by his unrecognizable signature.

Perhaps the writer had only meant it as a joke, a sabotaging wink to the boys behind their mother’s back; or else it’d been more than a joke, and he’d felt called to reveal an absolute truth that a child did not learn from his parents. “Unacceptable,” Ruyu said, and folded up the shirts.

“Now, what do I do with them? I promised the boys I would get them his signature. How do I explain to them that this person they admire is a jerk? An asshole, really,” Celia said, and gulped down some wine as if to rinse away the bad taste. “Thank goodness Edwin picked them up from school so I didn’t have to deal with this until later.”

Poor gullible Celia, believing, like most people, in a moment called later. Safely removed, later promises possibilities: changes, solutions, rewards, happiness, all too distant to be real, yet real enough to offer relief from the claustrophobic cocoon of now. If only Celia had the strength to be both kind enough and harsh enough with herself to stop talking about later, that heartless annihilator of now. “Exactly what,” Ruyu said, “will you say to them later?”

“That I forgot?” Celia said uncertainly. “What else can I say? Better for your children to be annoyed with you, better for your husband to be disappointed by you, than break anyone’s heart. I’ll tell you, Ruby, it’s smart of you not to have children. Smarter of you to not want another husband. Stay where you are. Sometimes I think about how simple and beautiful your life is—and that, I say to myself, is how a woman should treat herself.”

Had Celia been a different person, Ruyu might have found her words distasteful, malicious even, but Celia, being Celia, and never doubting the truth of her own words, was as close to a friend as Ruyu would admit into her life. She unfolded the shirts and studied the handwriting, and asked Celia if she had another pair of white T-shirts. Why? Celia asked, and Ruyu said that they might as well fix the problem themselves. You don’t mean it, Celia said, and Ruyu replied that indeed she did. What’s wrong with borrowing the writer’s name and making two boys happy?

Celia hesitantly offered another set of T-shirts, and Ruyu asked Celia what message she wanted her children to wear to school.

“Are you sure this is the right thing to do? I don’t want my children to think I lie to them.”

The writer, Ruyu wanted to remind Celia, had not lied. “I’m the one lying here,” she said. “Look away.”

“What if the other kids at school realize that the signatures are fake? Is it even legal to do this?”

“There are worse crimes,” Ruyu said. Before Celia could protest, Ruyu wrote, in her best approximation of the writer’s handwriting, a message of hope and affection to the beloved Jake and Lucas. After signing and dating the shirts, Ruyu folded them and said she would get rid of the original evidence to spare Celia any wrongdoing.

A car engine was heard outside the house; another car door opened and then closed. Celia’s guests were arriving, and she assumed the nervous, high-pitched energy of onstage-ness. Ruyu waved for Celia to go and greet her guests. She stuffed the two unwanted T-shirts in her bag, went into the boys’ bedrooms, and placed the ones she’d signed on their pillows.

The evening’s topic was a recent bestseller written by a woman who called herself a “Chinese tiger mom.” As always the gathering started with the exchange about children and husbands and family vacations and coming holiday recitals and performances. Ruyu drifted in and out of the living room, refilling wineglasses and passing out food, her position somewhere between a family friend and a hired hand. Affable with the guests, many of whom used her service in one way or another, Ruyu nevertheless stayed out of conversations, contributing only an encouraging smile or a courteous exclamation. Knowing how the women saw her, Ruyu did not find it difficult to play that role: an educated immigrant with no advanced job skills; a single woman no longer young; a renter; a hire trustworthy enough, good and firm with dogs and children alike and never flirtatious with husbands; a woman lucky to have been taken under Celia’s wing; a bore.

When the book discussion began, Ruyu withdrew to the kitchen. At most gatherings she would not have absented herself so completely, as she did enjoy sitting on the periphery. She liked to listen to the women’s voices without following what they said, and look at their soft-hued scarves, their necklaces designed by a local artist they patronized as a group, and their shoes, elegant or bold or unself-consciously ugly. To be where she was, to be what she was, suited her. One would have to take oneself much more seriously to be someone definite—to pose as a complete outsider; or to claim the right to be a friend, a lover, a person of consequence. Intimacy and alienation both required an effort beyond Ruyu’s willingness.

Celia stopped at the entrance to the kitchen. “Don’t you want to sit with us?” she asked. Ruyu shook her head, and Celia waved before walking away to the bathroom. If Celia pressed her again, Ruyu would say that the topics of parenting, school options for children, and the tiger mom—who was not even Chinese but called herself Chinese for sensational reasons—held little interest for her.

Ruyu studied the flowers on the table, an assortment of daisies and irises and fall leaves arranged in a half pumpkin, around which a few persimmons had been artfully placed. She moved one persimmon farther away and wondered if anyone would notice the interfered-with composition, less balanced now. Celia’s life, busy and fluid with all sorts of commitments and crises, was nevertheless an exhibition of mindfully designed flawlessness: the high, arched windows of her home overlooked the bay, inviting into the living room an ever-changing light—golden Californian sunshine in the summer afternoons, gray rain light in the winter, morning and evening fog all year round; the three silver birch trees in front of the house—birch, Celia had told Ruyu, must be planted in clusters of three, though why she did not know—complemented the facade with their white bark, adding asymmetry to the otherwise tedious front lawn; the shining modernness of the kitchen was softened by a perfect display of still lifes—fruits, flowers, earthen jars, candles in holders, their colors in harmony with seasons and holidays; and the many corners in the house, each its own stage, showcased a lonely cast of things inherited or collected on this or that trip. Celia’s family, always on the run—soccer practice, music lessons, pottery classes, yoga, fundraising parties, school auctions, trips to ski, to hike, to swim in the ocean, to immerse in foreign cultures and cuisines—had done a good job of leaving the house undisturbed, and Ruyu, perhaps more than anyone else, enjoyed the house as one would appreciate a beautiful object: one finds random pleasure in it, yet one does not experience any desire to possess it, or any pain when it passes out of one’s life.

From the living room, the women’s voices meandered from indignation to doubt to worry to panic. Over the past few years Ruyu had got to know each of the women, through these gatherings and working for some of them, well enough to pity them when they had to come into a group. None of them was uninteresting, but together they seemed to negate one another’s individual existence by their predictability. Never did anyone show up disheveled, never did any one of them dare to admit to the others that she was lonely, or sad, or suffocated under the perfect facade of a good life. It must be the isolation that sent them to seek out others like them, but in Celia’s living room, sitting together, the women seemed only more bravely isolated.

Ruyu had first met Celia seven years ago, when Celia had been looking for a replacement for their live-in nanny, who was returning to Guatemala with enough money to build two houses—one for her parents, and one for herself and her daughter. Of course it crushed her heart that Ana Luisa had to leave, Celia had said when she called Ruyu, who had replied to Celia’s ad on a local parenting website; but wouldn’t anyone feel happy for her? Ruyu had been an oddity among the more ordinary applicants—she had no previous child-care experience, and she lived rather out of the way. But having a Mandarin-speaking nanny would be an advantage over having one who spoke Spanish, Celia had explained to Edwin before she called Ruyu.

She did not have a car, Ruyu had said when Celia invited Ruyu to the house for an interview, and there was no public transportation where she lived, so could Celia, if interested, drive down to interview her? Later, when Ruyu was securely placed in Celia’s life, Celia liked to tell her friends how wonderfully clueless Ruyu had been. Who, if not Celia, would have driven one and a half hours to meet a potential nanny?

Why indeed had she agreed, Ruyu wanted to ask Celia sometimes, but the answer was not important, as what mattered was that Celia did go out of her way to meet Ruyu, and—this Ruyu had never doubted—if not Celia, there would be someone else willing to do the same.

When Celia arrived at Ruyu’s cottage, which, with its own garden and views of the canyon, would have been called “a gem” in a real estate ad, Celia could not hide her surprise and dismay. There was no way she could afford Ruyu, she said; all she had was an au pair’s suite on the first floor of her house.

But that would suit her well, Ruyu said, and explained that her employer was getting married in a few months, and she would like to move away before the wedding, since there was no reason for her to stay on as his housekeeper. Celia, Ruyu could see, was baffled by the relationship between the cottage and the three-storied colonial on the estate, which Celia must have seen while driving past—as well as that between Ruyu and Eric, whom Ruyu only referred to as her employer.

Curious, Celia later described the Chinese woman to Edwin; peculiar even, but all the same she was pleasant, clean, spoke perfect English, and deserved some help. Ruyu had not talked about the exact nature of her relationship with her employer, but Celia had guessed rightly that sex, with an agreement, was part of the employment. About other things in her background, Ruyu had been open with Celia during that first meeting: she had married her first husband at nineteen, a Chinese man who had been admitted to an American graduate school; she’d married him to leave China. Her second marriage, to an American, was to get herself a green card, which her first husband would have eventually helped her get, but she did not want to stay in the marriage for the five or six years it would have taken. She’d earned a bachelor’s degree in accounting from a state university and had worked on and off but never really built a career, which was fine with her because she did not like numbers or money. For the past three years, she’d been working as a housekeeper for her employer, and she was looking forward to moving on—no, she didn’t mean to marry again, Ruyu had said when Celia, out of curiosity, asked her if she was going to look for another husband; what she wanted, Ruyu said, was to find a job to support herself.

When Celia called again, a week later, she did not offer Ruyu the nanny position but said that she had found a cottage, furnished, which would be available for three months during the summer. Would Ruyu be open to taking it—she’d have to pay the three months’ rent up front—and working for Celia on a part-time basis? She would be happy to help Ruyu settle down, find her another cottage after the summer, and refer her to a few other families who could use Ruyu here and there. Without hesitation Ruyu had said yes.

The garage door opened, the noise reminding Ruyu of the immodest grumbling from inside one’s stomach. She was fascinated, even after years in America, by the intimate contract that sound confirmed: a door opens and then closes, yet through it neither departure nor arrival is damagingly permanent. Sitting in Celia’s kitchen and listening to her husband’s return, Ruyu allowed herself, for a brief moment, to imagine the possibility of such a life. Not a difficult task, in fact, as two men among the people of the world had offered her that—yet in the end, she was the one who had left. Had she stayed in either marriage she would have had to become one of those women in the living room, and the thought amused her. “Your problem,” Eric had said when she informed him of her moving plan only after finalizing it with Celia, “is that you don’t want enough. Though I suppose that also means things will always work out for you.”

Eric had been wise not to over-offer, as her two ex-husbands had, but he did indulge her, granting her all the space she needed, and making clear she should never feel bound in any way to him. Sometimes she wondered if, for that reason, she should have treated him better. But how does one treat a man better—by becoming more dependent on him, by asking more from him? All the same, what was the point of thinking of that now? A few years ago, Eric had made the local news for his involvement in a fundraising scandal during his campaign for assemblyman—so much for his wanting more.

Celia, who must have been listening also, took leave of the discussion and told Ruyu to show the T-shirts to the boys, her pitch a bit high because, Ruyu knew, of her nervousness about lying to her family. It was in these moments that Ruyu felt a tenderness toward Celia, who, despite her constant need for attention and her petty competition with her friends and neighbors, was, in the end, a woman with a good and weak heart.

A while later, with the boys in bed, Edwin came into the kitchen. In the living room, the women were still arguing about the best way to bring up a child to be competitive in a global market. A heated discussion today, he commented, and touched the stem of a wine glass before changing his mind. He poured water for himself.

Certainly Celia had chosen the right book, Ruyu said, and moved to the sink before Edwin sat down at the table. “I’ll start to put things away,” she said. “Celia has had a long day.”

Edwin asked if he could help, though Ruyu could tell it was a halfhearted offer. Probably all he wanted was for the women debating the future of American education to vacate his house. There was not much she needed him to do, Ruyu said. Edwin kept the conversation going, talking about trivialities—the Warriors’ win that night, a new movie Celia was talking about going to see that weekend, the Moorlands’ Thanksgiving plans, a bizarre report in the paper about a man impersonating a doctor and prescribing his only patient, an older woman, a regimen of eating watermelons in a hot tub. Ruyu wondered if Edwin was talking to her out of a sense of charity; she wished she could tell him that it was okay for him to treat her, at this or any other moment, like a piece of furniture or appliance in his well-kept house.

Edwin worked for a company that specialized in electronic books and toys for early childhood learning. Though Ruyu did not know what exactly he did—it had something to do with creating certain characters appealing to the minds of toddlers—she wondered if Edwin, a tall and quiet man born and raised in the Minnesota countryside, would have been better off as a sympathetic family physician or a brilliant yet awkward mathematician. To spend one’s workdays thinking about talking caterpillars and singing bears seemed diminishing for a man like Edwin, but perhaps it was a good choice, the same way Celia was a good choice of wife for him.

“Things are well with you?” Edwin asked when he ran out of topics.

“How can they not be?” Ruyu replied. There was not much in her life that was worth inquiring about, the general topics of children and jobs and family vacations not an option in her case.

Edwin brooded over his water glass. “You must find their discussion strange,” he said, pointing his chin at the living room.

“Strange? Not at all,” Ruyu said. “The world needs enthusiastic women. Too bad I am not one of them.”

“But do you want to be one?”

“You either are one, or you are not,” Ruyu said. “It has nothing to do with wanting.”

“Do they bore you?”

She would not, if asked, have considered Edwin or Celia or any of her friends a bore, but that was because she had never really taken a moment to think about what Edwin, or Celia, or anyone else for that matter, was. Edwin’s face, never overly expressive, seemed particularly vague at the moment. Ruyu rarely allowed her interaction with him to progress beyond pleasantries, as there was something about Edwin that she could not see through right away. He did not speak enough to make himself a fool, yet what he did say made one wonder why he didn’t say more. Had he been no one’s husband she would have taken a closer look, but any impingement on Celia’s claim would be a pointless complication.

After a long pause, which Celia would have readily filled with many topics, and which Edwin seemed patient enough to wait through, Ruyu said, “Only a bore would find other people boring.”

“Do you find them interesting, then?”

“Many of them hire me,” Ruyu said. “Celia is a friend.”

“Of course,” Edwin said. “I forgot that.”

What was it he had forgotten—that the women in the living room provided more than half of Ruyu’s livelihood, or that his own wife was the angel who’d made such a miracle happen? Ruyu placed the plates in the dishwasher. She wished that Edwin would stop feeling obligated to keep her company while she played the role of half hostess in his house. In the cottage, she cooked on a hot plate and ate standing by the kitchen counter, and the dish drain, left by a previous renter, was empty and dry most of the time. In Celia’s house Ruyu enjoyed lining up the plates and cups and glasses, which, unlike people, did not seek to crack and break their own lives. When she continued in silence, Edwin asked if he had offended her.

“No,” she sighed.

“But do you think we take you for granted?”

“Who? You and Celia?”

“Everyone here,” Edwin said.

“People are taken for granted all the time,” Ruyu said. Every one of the women in the living room would have a long list of complaints about being taken for granted. “I’m not a unique case who needs special attention.”

“But we complain.”

Ruyu turned and looked at Edwin. “Go ahead and complain,” she said. “But don’t expect me to do it.”

Edwin blushed. Do not expose your soul uninvited, she would have said if Edwin were no one’s husband, but instead she apologized for her abruptness. “Don’t mind what I said,” she said. “Celia said I wasn’t my right self today.”

“Is anything the matter?”

“Someone I used to know died,” Ruyu said, feeling malicious because she would not have told this to Celia even if she were ten times as persistent.

Edwin said he was sorry to hear the news. Ruyu knew he would like to ask more questions; Celia would have been chasing every detail, but Edwin seemed uncertain, as though intimidated by his own curiosity. “It’s all right,” Ruyu said. “People die.”

“Is there anything we can do?”

“No one can do anything. She’s dead already,” Ruyu said.

“I mean, can we do something for you?”