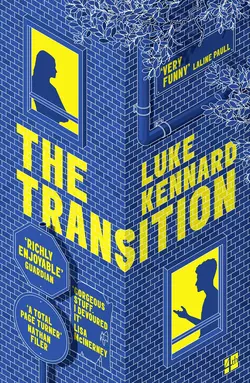

The Transition

Luke Kennard

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 612.81 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Black Mirror meets David Nicholls in this dark and funny novel about love in dystopian times