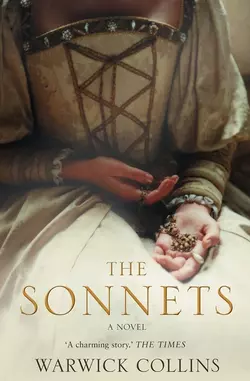

The Sonnets

Warwick Collins

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 152.86 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Shakespeare in Love for the sonnets: a fictional tale of how Shakespeare wrote his most famous poems.No one knows for sure precisely when and where Shakespeare wrote his sonnets or, more intriguingly, who he wrote them for. In this wonderfully entertaining novel acclaimed author Warwick Collins imagines the circumstances that inspired 30 of the Bard′s most popular sonnets.The young Will Shakespeare is living under the patronage of Henry Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton. The controversial earl is under pressure from his family and those close to the royal court to settle down but he is far too busy drinking, carousing and cavorting with his motley band of acquaintances to pay attention. Not then, the obvious setting for poetic genius but within the politics (both State and sexual) of this lofty household Will finds lots to inspire his pen, and a few attractive distractions too.Collins has crafted a clever, witty and enjoyable novel from fragments of history. He interweaves 30 sonnets into the text in seamless fashion. The Sonnets wears its scholarship lightly and its love of Shakespeare and poetry proudly.