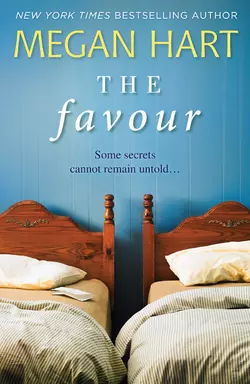

The Favour

Megan Hart

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 463.36 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Janelle Decker has happy childhood memories of her grandma’s house, and even lived there through high school. Now she’s back with her twelve-year-old son to look after her ailing Nan, and hardly anything seems to have changed, not even the Tierney boys next door.Gabriel Tierney, local bad-boy.The twins, Michael and Andrew.After everything that happened between the four of them, Janelle is shocked that Gabe still lives in St. Mary’s. And he isn’t trying very hard to convince Janelle he’s changed from the moody teenage boy she once knew. If anything, he seems bent on making sure she has no intentions of rekindling their past.To this day, though there might’ve been a lot of speculation about her relationship with Gabe, nobody else knows she was there in the woods that day… the day a devastating accident tore the Tierney brothers apart and drove Janelle away.But there are things that even Janelle doesn’t know, and as she and Gabe revisit their interrupted romance, she begins to uncover the truth denied to her when she ran away all those years ago.