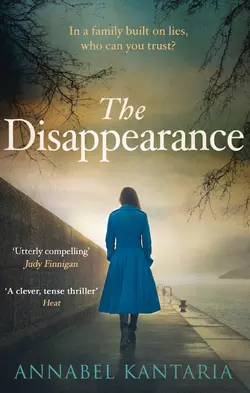

The Disappearance

Annabel Kantaria

‘Utterly compelling.’ – Judy FinniganIn a family built on lies, who can you trust?Audrey Bailey will never forget the moment she met Ralph Templeton in the sweltering heat of a Bombay café. Her lonely life over, she was soon married with two small children. But things in the Templeton household were never quite what they seemed.Now approaching 70, and increasingly a burden on the children she’s never felt close to, Audrey plans a once-in-a-lifetime cruise around the Greek isles. Forcing twins Lexi and John along for the ride, the Templetons set sail as a party of three – but only two will return.On the night of her birthday, Audrey goes missing…hours after she breaks the news that the twins stand to inherit a fortune after her death. As the search of the ship widens, so does the list of suspects – and with dark clues emerging about Audrey’s early life, the twins begin to question if they can even trust one another…

ANNABEL KANTARIA is a British journalist who now lives in Dubai with her husband and children. She has edited and contributed to women’s magazines and publications throughout the Middle East. The Disappearance is her second novel.

The Disappearance

Annabel Kantaria

Also by Annabel Kantaria (#ulink_4b290595-cb8c-590e-87dc-5e9d97b6c0c4)

Coming Home

For Maia and Aiman

Acknowledgements (#ulink_eca7fd09-07e7-5d5f-8819-5a3ed5ce599e)

A massive thank you to the wonderful people who helped bring this book to fruition: my inspirational agent Luigi Bonomi, Alison Bonomi, and my brilliant editor, Sally Williamson. Thank you, too, to all those beavering away behind the scenes at Harlequin to get the book produced, printed, marketed, publicised and sold. Thank you, too, to my friend and best beta reader ever, Rachel Hamilton.

A special thank you to all at the Emirates Airline Festival of Literature – in particular Isobel Abulhoul and Yvette Judge, and to Charles Nahhas of Montegrappa.

I’d also like to thank my parents-in-law, Natu and Niru Kantaria. It was with them that I first set foot on a cruise ship, and it was on that ship that the idea for this story was born (before you ask: yes, we all made it back to shore). Thank you, too, to all those who read and enjoyed Coming Home; and to all the wonderful book clubs who’ve invited me to join them for an evening of book chat.

Last, but not least, thank you to my cheerleaders: those wonderful friends who stand quietly behind me, cheering me on – you know who you are; thank you to my mum, and to my special little family: Sam, Maia and Aiman.

Table of Contents

Cover (#uc38e8ad7-41a5-555d-90e8-65a2719ece31)

About the Author (#ub3734acb-bf1f-5cf7-9ded-3e8c304a4252)

Title Page (#uc65e8f89-2e34-5e2e-b105-065b15ba4516)

Also by Annabel Kantaria (#ue626673e-4d52-54e4-8ed9-090ca91ef0b0)

Dedication (#ud523cc22-ebbe-57de-9492-5f4b442a738d)

Acknowledgements (#u07d5ee0d-6a99-5bd1-bb50-224a12e33198)

18 July 2013, 10 p.m. (#ua8014719-5f18-553b-8d9a-c74250677a48)

PART I Before (#u85e14904-b408-5aca-b19e-62b7d456c996)

December 1970 Tilbury, England (#u28d59bbb-4901-5c69-8993-2bde410b4d31)

November, 2012 Truro, Cornwall (#u2a78b559-773b-5b58-95b9-3007d073240e)

January 1971 Bombay, India (#uf0d8a917-17d6-51c9-8915-322380fb8571)

March 1971 Bombay, India (#u02ead661-ef7e-5b41-9b61-960e83b63427)

November 2012 Truro (#u419adc19-414b-50a9-b999-fd4f08c9aaab)

March 1971 Bombay, India (#u22a48d1a-29d4-5220-9136-2adf95f27219)

April 1971 Bombay, India (#ua7306f19-5068-5e72-aa0e-b61efa5ed1af)

November, 2012 St Ives, Cornwall (#u4814d5a4-82d5-57ab-96f5-4e9817d588e1)

July 1971 Bombay, India (#u7b0e49e4-3485-5804-b5a3-8bcb5191ee9b)

15 July 1971 Bombay, India (#u8cbcc8b7-93c3-52ec-8d9c-f11cca5f2ca0)

November 2012 Penzance (#u16a005e3-bae8-5a2c-9c80-25256b0ae6f2)

July 1972 Bombay, India (#ud53d93b1-5026-5563-ae7b-c9f3db0f2ce0)

January 2013 St Ives (#u529c0ce8-c97b-51cc-a4e8-d6ae69e925cb)

August 1972 Bombay, India (#uc84fc2df-13b6-54bb-9710-bb3d0f47949f)

February, 2013 Penzance, Cornwall (#u86ea8ef6-e1d8-54ba-8477-5d8a9823a11d)

15 July 1973 Barnes, London (#u55cbb6a0-dbc2-5082-b93f-9f12157eb343)

September 1976 Barnes, London (#litres_trial_promo)

March, 2013 Penzance, Cornwall (#litres_trial_promo)

December 1976 Barnes, London (#litres_trial_promo)

June 1976 Barnes, London (#litres_trial_promo)

April 2013 St Ives, Cornwall (#litres_trial_promo)

December 1976 Barnes, London (#litres_trial_promo)

April, 2013 St Ives, Cornwall (#litres_trial_promo)

April 2013 St Ives, Cornwall (#litres_trial_promo)

December 1976 Barnes, London (#litres_trial_promo)

December 1976 Barnes, London (#litres_trial_promo)

April 2013 Truro, Cornwall (#litres_trial_promo)

15 July 1978 Barnes, London (#litres_trial_promo)

Part II During (#litres_trial_promo)

12 July 2013, 8 a.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

12 July 2013, 4 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

14 July 2013, 9 a.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

14 July 2013, 11 a.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

14 July 2013, 11 a.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

14 July 2013, 8 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

14 July 2013, 10.15 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

15 July 2013, 7.30 a.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

15 July 2013, 10 a.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

15 July 2013, 11 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

16 July 2013, 9 a.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

16 July 2013, 5 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

17 July 2013, 8 a.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

17 July 2013, 3 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

17 July 2013, 3.45 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

17 July 2013, 5 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

17 July 2013, 5.30 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

17 July 2013, 6 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

18 July 2013, 9 a.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

18 July 2013, 10.30 a.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

18 July 2013, 8.30 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

18 July 2013, 10 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

18 July 2013, 11.30 p.m. (#litres_trial_promo)

PART III Before (#litres_trial_promo)

September 2012 St Ives (#litres_trial_promo)

November 2012 Truro (#litres_trial_promo)

November 2012 Truro (#litres_trial_promo)

November 2012 St Ives (#litres_trial_promo)

December 2012 Truro, Cornwall (#litres_trial_promo)

April 2013 (#litres_trial_promo)

April 2013 (#litres_trial_promo)

April 2013 St Ives, Cornwall (#litres_trial_promo)

PART IV After (#litres_trial_promo)

September 2013 Truro, Cornwall (#litres_trial_promo)

September 2013 Truro, Cornwall (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Endpage (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

18 July 2013, 10 p.m. (#ulink_7f3e9696-46c3-54ca-a185-8d121151cbea)

Captain Stiegman’s gaze swept around the ship’s library, shifting like a search light until it had touched everyone in the room. He took a deep breath, steadied his hands on the back of a chair and spoke. ‘The search has been called off.’

I pressed my hand to my mouth, stifling sob. Even though I’d been primed to hear these words, the sound of them left me winded: until now I’d still held out hope. There had been a mistake; Mum had been picked up by another ship. She’d been brought aboard, cold, weak, wrapped in a silver blanket, but alive. She’d floated on her back; she’d clung onto some flotsam; she’d been rescued by a lifeboat. Failing any of those scenarios, her body had been recovered. Anything but this; this inconclusive conclusion.

Captain Stiegman stood motionless. He was waiting for a response. I looked at John. He didn’t meet my gaze. He was looking at the floor, his thin lips pressed in a hard line, his expression inscrutable. The only part of my brother that moved was his hand, his fingers tapping a rhythm on the arm of the stuffed leather armchair. I wanted to speak but there were no words.

Captain Stiegman paced the library floor, his steps lithe in his rubber-soled shoes. Doris, the cruise director, stood awkwardly by the bookshelves, a walkie-talkie in her hand, her lipstick rudely red. Outside the picture window, small whitecaps topped the ocean like frosting. I imagined my mother’s arms poking desperately up from the crests of each wave, her mouth forming an ‘O’ as the lights of the ship faded into the distance. In the library, you couldn’t feel the low rumble of the ship’s engines that permeated the lower decks, but snatches of a Latin beat carried from the Vida Loca dance party taking place on the pool deck outside. Doris’s walkie-talkie crackled to life then fell silent.

‘The decision has not been taken lightly,’ said the captain, his English curt with a German accent, his words staccato. ‘We have to face the facts. Mrs Templeton has been missing for over forty hours. The ship was sailing at full speed on the night she was last seen. We have no idea when she went overboard, nor where – the search area covers thousands of square kilometres.’

He paused, looked at John and me, then—perhaps heartened by the absence of tears – continued, ticking off points with his fingers as he spoke. A band of dull platinum circled his wedding finger.

‘As you are already aware, I did not turn the ship. This was because, with Mrs Templeton missing for thirty-nine hours before the search was initiated, I felt there was nothing to be gained by retracing our route. It is my belief that Mrs Templeton did not fall overboard shortly before she was reported missing, but many hours prior to that, most likely in the early hours of the sixteenth of July.’

I opened my mouth to speak – this was pure supposition – but the captain raised his hand in a request for me to be patient. ‘However,’ he said, ‘tenders were dispatched from both Mykonos and Santorini, which is the area in which the ship was sailing when Mrs Templeton was last seen. A fleet of tenders traced our route from either end.’ Now he paused and looked at each of us in turn once more. I gave a tiny shake of my head, eyes closed; there was nothing I could say to change what had happened.

‘The Coast Guard was informed as soon as the ship search yielded nothing,’ continued the captain. ‘Two helicopters were scrambled and all ships within a thirty kilometre radius of the course we took that night were asked to join the search.’ He paused again, looked at his shoes, then up again. ‘I believe there were five vessels involved. The search has been fruitless. Mrs Templeton could now have been in the water, without a floatation device, for up to forty-eight hours. She was …’ he searched his memory … ‘seventy years old?’ His voice trailed off and he looked again at John, then at me, his eyebrows raised, the implication clear: she could not have survived.

John closed his eyes and nodded almost imperceptibly. Captain Stiegman echoed the nod. I opened my mouth then shut it again.

‘Thank you,’ said the captain. He bowed his head; looked up again after a respectful pause. I felt the thump of the music from outside. ‘With the engines on full power, we should make Venice by dawn. I’m obliged to inform local police we have one passenger lost at sea. They will come aboard. They will talk to you. In a case like this, it is a formality.’ He removed his captain’s hat, held it to his chest, his eyes closed again for a second. ‘I am sorry for your loss.’

PART I (#ulink_7ef3d9e1-9b7c-5849-8830-8ce606fc617a)

December 1970 (#ulink_40fbb62e-2d5e-5f1e-95bd-68d1e7ec44da)

Tilbury, England (#ulink_40fbb62e-2d5e-5f1e-95bd-68d1e7ec44da)

Audrey Bailey is on deck as the SS Oriana finally begins to ease her way backwards out of the dock. Someone’s given her a streamer, but she’s holding it clenched in her fist as she stands cheek by jowl with the other passengers and stares silently at the crowds on the quay. Everyone’s waving flags, calling and shouting to friends and relatives. A band’s playing onshore, and she can hear the rousing rhythm of sea shanties. The din is unbearable.

Then, as Audrey stares at the mass of humanity below, she catches sight of something that takes her breath away; the shape of a man, the colour of his hair, and the way he moves his arm as he waves a white hankie at the ship. Reflexively, Audrey raises her hand and waves back, knowing even as she does that it can’t be; it can’t be her father.

‘Bye,’ she mouths, the words silent on her lips. ‘Bye Daddy.’

Audrey’s hand remains in the air for a second or two as she turns her eyes to the sky, overcome with emotion. Then she turns abruptly and pushes her way back through the crowds, no longer willing to witness the ship’s departure. She walks until she finds a deck that’s less populated, sinks into a deckchair and tries simply to exist. All that is her, all that is Audrey Bailey, is gone. Her body is a shell, the softness inside her decimated. She sits in the deckchair for a long time, her head bowed; her eyes closed, just breathing. In, out, in, out, in, out. If I do this enough, she thinks, this day will end. And then I will do the same tomorrow. I will get through this. One day at a time.

Oblivious to her surroundings, Audrey does nothing but exist.

After some time – maybe an hour; maybe more – Audrey feels the rhythm of the engines move up a notch; she senses faster movement. She opens her eyes slowly and looks up. Her hair’s whipped by a fresh breeze and she sees that the ship’s already at sea. Slowly, she walks to the railing and stares down at the murky grey-brown water.

There are plenty more fish in the sea.

Audrey tries to see through the water; tries to seek out something – anything – of the sea life that must swim far beneath the shipping lane.

So where are they – these famous fish? If I had a penny … Audrey shakes her head to stop the thought. She’s had it so many times she doesn’t even need to complete the sentence: if she had a penny for every time some well-meaning person’s given her arm a sympathetic rub and told her that Patrick ‘clearly wasn’t the right one for you, dear’ and that there are ‘plenty more fish in the sea’, she’d have been able to afford proper nursing care for her dad, and given herself a bit of a break. Maybe then Patrick would have stayed. It’s a circular thought; one that’s now so familiar it’s become part of the fabric of her being.

Audrey looks up. In the distance she can see land. It’s still England, she presumes, and she feels a curious detachment from the leaving of her homeland for the first time in her life. There’s nothing there for you anymore, she tells herself. Nothing. She’s adjusted as much as anyone can to losing her mother at a young age; now her father – her rock – has gone, too: a stroke, a painfully slow recovery, and then another, massive stroke.

Audrey swallows a sob. Since the funeral, Audrey’s been haunted by dreams –cruel dreams in which both her parents are still alive—and then she wakes, sweating, in the early hours, plagued by the terror that she’s suddenly alone in the world. But, rather than lie in bed panicking, Audrey’s learned to get up – at 3.30 a.m., at 4 a.m. – and to pace the worn-out carpet of her rented studio. She tries to outwalk the fear of being alone: no parents, no fiancé, no plans, no life.

Now, standing on the deck of SS Oriana, she takes a deep breath. Her life is changing. Changing for the better. She rummages in her coat pocket and pulls out an aerogramme, the thin paper covered in loops of blobby blue biro.

‘Dear Audrey,’ she reads, although she’s read it so many times, spent so many nights thinking about it, she knows it off by heart. ‘My parents told me about your father. I know we haven’t been in touch for a while, but I wanted to reach out and let you know I’m thinking of you. I’m so sorry. I just can’t imagine what you must be feeling.

‘I hear you’re a legal secretary in London. I always knew you’d get a good job: you were always top of the class. I’m based in Bombay now – yes, Bombay! I know! I work for a shipping firm and I like it here very much. But what I wanted to say is if you ever feel a need to get away; if things get too much for you in England, come to India. The P&O line sails to Bombay from Tilbury and Southampton. I’d love to see you – and sometimes a change of scene can really help.

‘Much love, Janet’

Audrey looks up from the letter, a picture of Janet’s face in her mind’s eye. Dear, sweet Janet. It’s fate, Audrey thinks. She has the sense that, somehow, from beyond the grave, her father has pulled strings to get this invitation to her because sailing to India is the right thing for her to do. Her parents met and married in Bombay and Audrey’s grown up with stories about this exotic land of palm trees and British buses, of chai wallahs and Rupees – she’s always felt a pull. So, yes, today Audrey is sailing away from England. It might just be for a holiday – but, equally, it might be forever.

November, 2012 (#ulink_1883eabb-47d4-51c2-8fed-4565ec386c1f)

Truro, Cornwall (#ulink_1883eabb-47d4-51c2-8fed-4565ec386c1f)

It started the day Mum crashed her car. It was a Saturday morning and the rain was coming down so hard it didn’t look real; it was special-effect, Hollywood rain. Outside the supermarket, but still undercover, I stood for a moment and surveyed the scene: the clouds were so low they looked like they were trying to land on the trees. The tarmac was slick with rain, and cars circled like sharks, wipers swishing as their drivers hunted for somewhere to park – it was nearly lunchtime and, inside, the supermarket had been teeming.

Already I was tired, feeling a little faint; hoping with all my heart that the faintness could mean something other than my having skipped breakfast. With my mind on the tiny life that I wanted so badly to believe was growing in my belly, I took a deep breath and, shopping bags banging my shins, dashed in the direction of my car, fat drops of rain plastering my hair to my head. By the time I reached the row where my car was parked I was soaked. A car crawled at my heels, eager for my space, and I jerked my head towards where my car was, willing the driver to be patient.

I opened the boot and threw the shopping bags in, slammed down the lid, and slid into the driver’s seat, trying to shrug off my wet coat as I went. I fastened my seatbelt, started the engine, shifted gear, then put the car into reverse. The phone rang and my body reacted viscerally: a quickened pulse, a catch of my breath. I’d waited all morning for a call from the doctor.

My eyes snapped to the dashboard display: not the doctor. John.

‘Really?’ I sighed. I almost didn’t pick up, scared I’d miss the doctor’s call if I did. But John must be calling for a reason; my twin never phoned just for a chat. With a sigh, I tapped the Bluetooth to connect and started to reverse the car out of the space.

‘Lex? Is that you?’ John’s voice filled the car. ‘I’ve been trying you for ages.’

‘I’m out,’ I said. ‘What’s up? Is Mum okay?’

‘Well, that’s why I’m calling.’

Out of the parking space, I eased the car through the congested car park and onto the road.

‘What? What’s happened? Is she okay?’

‘She’s had a car accident.’

‘Oh my God! Is she all right?’

‘I’ve just spent half the night and most of this morning at the hospital. But she’s all right. Ish.’

‘What do you mean “ish”? She’s either okay or she’s not okay!’ My voice rose.

‘She’s fine. No broken bones. It happened late last night. I tried to call you but your phone was off. What were you thinking letting her drive back from Truro so late? You should have asked her to stay – or at least dropped her off yourself!’

Mum and I had gone to an exhibition of old photos of India the night before. I hadn’t seen the attraction myself, but Mum had lived there for a bit when she was younger and still got a bit misty-eyed about it. She’d asked me to go with her, given it was within walking distance of my house. John had refused point-blank to drive her up from St Ives; I’d half-heartedly offered to come down and pick her up but she’d insisted on driving herself and, distracted by the thought I might finally be pregnant, I’d given in – way too easily, I realised now.

‘I did ask her to stay! When I realised how late it was, I asked her to stay! She refused. You know what she’s like.’

John tutted. ‘At the very least, you could have kept your phone on.’

I started to argue then remembered that the battery had gone flat and I’d fallen into bed exhausted when I’d got back, forgetting to put it on to charge. Mark and I didn’t have a landline.

‘Oh God,’ I said. ‘Flat battery.’

‘Well, that’s very convenient,’ said John. ‘So it was me they called in the middle of the night. They took her to hospital. Kept her in overnight.’

‘You said she was okay! Why did she have to stay in?’

‘She hit her head; strained her neck; got a few bruises. They just wanted to observe her.’

‘Did you stay with her?’

‘No. She didn’t want me to. Anyway, they discharged her this morning on condition that someone stays with her tonight. She’s been in shock and may have whiplash. They don’t want her to be alone.’

‘Okay.’ I waited for John to tell me he was going to stay with Mum. It made sense given how much closer he lived.

‘So, that’s why I’m ringing,’ he said. ‘Can you come?’

‘Me?’

‘Yes, you, Lexi. I can’t stay with her any more. I’ve done my bit. The twins are at a swimming gala this afternoon and Anastasia will kill me if I’m not there.’ John pronounced his wife’s name with a long ‘a’ and a soft ‘s’, emphasis on the middle syllable: Anna-star-seeya. Never ‘Anna-stay-zia’. It still blew my mind that my rather unemotional and unspontaneous brother had come back from a holiday to Estonia not just with a beautiful wife and two ready-made children, but with his new mother-in-law, too.

‘But …’ I thought about the call I was waiting for from the doctor. I had a mountain of marking to do and all I really wanted to do was curl up on the sofa and nurture the life I was convinced was growing inside me, not drive down to St Ives in the pouring rain and play nursemaid to Mum.

‘Please can you do it, John?’ A sob caught in my throat. ‘Please?’

John sighed. ‘I’m asking you nicely, Lexi. But it really is your turn.’ There was a silence. ‘Look. Isn’t this why you moved to Cornwall? So you could help out a bit, too?’ The implication was there: until Mark and I had moved to Truro six months ago, John had borne the brunt of looking after Mum while I ‘ignored my responsibilities’ – John’s words – up in London.

Knowing he had the moral high ground, John continued almost seamlessly. ‘How quickly can you be there? I dropped her off just now, so the sooner, the better, really.’

‘You left her alone? Fantastic.’ I slammed the brakes on as a car pulled out in front of me.

‘I had to go, Lexi,’ John said, his voice slow and deliberate. ‘I have a family, remember? I’ve already spent half the night with her at the hospital. And then I scrapped our plans for the morning. I sorted out the insurance. I organised her car to be picked up, I took her home from the hospital and now I’ve made her comfortable. She’s not very chatty – she’s on the sofa, looking a bit dazed. I left her with a crossword. She’ll be fine until you get there.’

Silence hung heavy on the line. A silence in which I realised that I had no choice. I indicated and turned into my road, the car’s tyres swishing through puddles.

‘Are you driving?’ John asked.

‘Yes.’

‘Oh. You can call me back when you get in, if you want.’

‘No it’s okay. Hands-free.’ I paused. ‘Okay, I’ll come down.’

‘Thanks.’

I pulled into a rare parking space right outside my house, sending a silent thank you to the gods as I did so.

‘By the way,’ said John. ‘While you’re there, can you observe her a bit? I mean, more than usual? I thought she was acting a bit odd, like she wasn’t all there. She was just sitting there this morning, staring into the distance. It’s like she’s in a different world. I’m worried the hospital might have missed something. You know – with the bang on the head.’

‘Sure. But I can’t go for an hour or two. I need to speak to Mark and he’s not due back for a bit.’

‘Okay,’ said John. ‘Thanks, Lexi. Bye.’ The line disconnected and my phone buzzed at once: a missed call from the doctor’s number, followed by the beep of a text message asking me to call. I dialled in.

‘Mrs Scrivener,’ the doctor said when my call was put through. I heard papers rustling; imagined her looking for my test results. ‘How are you feeling?’

‘Fine, thank you,’ I said. ‘A bit tired.’

‘Okay. Well, the results of your blood test are back.’ She paused.

‘And?’ I said.

‘Your hCG level is very low.’

‘What does that mean? Am I pregnant?’

The doctor sighed. ‘Well. It’s really too low for a healthy pregnancy.’

‘What do you mean? I might not be? The test I did at home was positive. I did two really sensitive tests! Both were positive!’

The doctor’s blood test was supposed to be a rubber-stamp of news I already knew. How could it not be certain when the over-the-counter test had been?

The doctor sighed. ‘It’s possible that something started and is now failing. A lot of pregnancies fail very early on, before many women even suspect they might have been pregnant. Sometimes, testing very early can backfire …’ Her voice was gentle. She paused and I didn’t say anything.

I’d been so certain. I’d even felt faintly sick this morning. I thought about the tiny babygros I’d just been stroking in the supermarket just now; the white Moses basket I’d picked out online. White because, although I hoped for a girl, I didn’t want to know the sex.

‘I’m very sorry,’ said the doctor.

‘I … just … I wasn’t expecting this.’

‘I know. It’s very common, though. More common than you’d think.’

‘Is there anything I can do? To increase my chances next month?’

‘Just be kind to yourself. Eat well, exercise. Get enough sleep. Take it easy and try not to worry.’

Try not to worry! ‘Okay,’ I said. ‘Thank you.’

I pressed disconnect and let my forehead slump onto the steering wheel as I wrapped my arms around myself. I’d been so sure this time! How could I not be pregnant? Even though it was very early days, I’d felt all the classic symptoms. The last thing I felt like now was driving down to St Ives to look after Mum. As soon as I’d thought it, guilt washed over me. John had done his bit and I’d still expected him to do more. But that guilt was nothing compared to the guilt I felt about the pregnancy. Why couldn’t I give Mark a baby? What was wrong with me?

Deep down, I knew the answer: at forty-two, time was hardly on my side.

January 1971 (#ulink_4bda9262-54d9-53e3-ad4c-ab68139fdecf)

Bombay, India (#ulink_4bda9262-54d9-53e3-ad4c-ab68139fdecf)

When Audrey wakes up, the first thing she notices is the stillness. The small room in which she’s lying in a tangle of sweaty sheets isn’t by any means silent – the din of Bombay is alive right outside the window – but the absence of the rumble of the ship’s engine rings louder than it ever did on the ship. A week after she’s arrived, Audrey’s still acclimatising to being on land. Truth be told, she’s slightly terrified of Bombay and has hardly ventured out unless Janet’s there, literally to hold her hand, to guide her across the streets, to fend off the beggars and street hawkers that swarm around them, and to flag down rickshaws the two of them use to get anywhere too far to walk.

But today Audrey has a plan. Today is the first day she’s going to take on this strange city alone; to conquer a corner of it. On the small table that counts both as Janet’s dressing and dining table, there’s a copy of Audrey’s parents’ wedding certificate, which names the small church in which they were married. Janet’s asked around for her at work, and Audrey now has a hand-drawn map showing her how to find it. For the first time since she’s arrived in Bombay she gets up with a purpose in her step. She washes quickly and dresses, makes some toast, and steps out into the chaotic street, where the warmth of the January air hits her.

Audrey stands still for a second, feasting her eyes on the dusty palm trees that look so exotic to her, their heavy fronds dancing likes drunken spiders in the breeze. This is home now, she thinks, even while her senses revel in everything that’s unfamiliar: the smells, the furious honks of car horns and the shouts in Hindi, Marathi, and a tangle of other languages – a gabble of sound she’s unable to decipher.

Audrey’s memorised where she needs to go – it’s not far – and she walks as quickly as she can, trying, but not always managing, to stick to pavements while avoiding pedestrians, traffic, and holes in the road. Ahead of her there’s a commotion and she sees the traffic’s come to a halt as a couple of cows amble about in the middle of the road. Janet’s explained to her that this is perfectly normal, and it’s exactly how she imagined Bombay would be, but she still can’t believe her eyes. Someone’s trying to lead the cows off the street so traffic can pass, but no one except her seems to bat an eyelid at the strange juxtaposition of cows, cars, bicycles, and bullock carts that makes up this pungent traffic jam. As Audrey watches, one of the cows lifts its tail and deposits a steaming cowpat in the middle of the road. Audrey turns down a side street just before the smell hits her.

At first she doesn’t see the church. It’s not big, and it doesn’t stand out from the dirty buildings surrounding it. She double-checks her map, then stands back on the other side of the street and scans the facades to be sure she’s in the right place before she goes in. Yes, it looks nothing like the churches she’s used to back home, but there’s a steeple peeping out from behind a dusty tree. It’s definitely the church. Audrey takes a deep breath, closes her eyes, and imagines her mum arriving for her wedding, picking her way down the street in her finery knowing her groom was waiting inside the church. Holding the image in her head, she pushes open the heavy wooden door and enters.

It takes a minute for Audrey’s eyes to become accustomed to the gloom of the interior after the bright sunshine outside so she stands still, taking in the sparse wooden pews – perhaps only seven or eight rows – and the small altar at the front. Dust motes dance in the sunbeams that penetrate the stained glass windows. When her eyes have adjusted, Audrey walks slowly down the aisle, picturing her mum doing the same on her wedding day, a small posy of garden flowers clasped at her chest. At the altar she stops, closes her eyes, and stands in silence, feeling the moment.

‘Can I help you?’ A woman’s voice cuts in and Audrey’s eyes snap open. She spins around.

‘Oh, hello,’ she says. ‘I hope you don’t mind … I … I think my parents were married in this church and I just wanted to come and see it.’

‘Lovely! Welcome.’ The woman waves her hand at the church’s interior. ‘Please stay as long as you like. When was the wedding? I could possibly dig out the record for you.’

‘Oh, could you? That would be fantastic! They were married in 1940.’

The woman looks thoughtful. ‘Yes. I’m sure we have those records. I’d need a day or so to find it but I could definitely get it out for you. Do you know which month?’

‘Yes – June.’

‘Okay, well, if you’d like to pop by again tomorrow I’ll have it ready for you.’

‘Thank you so much! It’s incredible. I’m here now, where they got married. I can almost feel them here.’

‘Have they been back themselves?’

‘No – they’re – they passed away.’

‘I’m so sorry to hear that. Well, you’re most welcome. Whenever you like. Just come. The door’s always open.’ The woman gives Audrey a kind smile and turns back to the ante-room from which she came. Audrey sits gingerly on the front pew and closes her eyes. As the peace settles around her, Audrey can feel the essence of her dad. It’s as if a part of him is here in this church. She’s grown up with stories of him coming here every Sunday; of him wading through the monsoon rains or sheltering from the sun under an old umbrella on his weekly walk to this very place. This church has been a part of her childhood and now here she is. A smile washes over Audrey’s face, and, perhaps for the first time since her father died, her whole body relaxes.

March 1971 (#ulink_ee65d7c3-95c5-5cd8-a7e8-8088ce75d361)

Bombay, India (#ulink_ee65d7c3-95c5-5cd8-a7e8-8088ce75d361)

Audrey and Janet walk arm in arm down Churchgate after dinner. In the distance, they spot a busy café, and the sound of its resident jazz trio floats to them on the night air. The street is alive with sounds, smells, and people. Audrey breathes deeply, inhaling the scent of this exotic city and revelling in the warmth that still comes as a surprise to her every time she steps outside. In England it’d still be coat weather. Janet looks longingly at the crowd of suited and booted punters that spills into the café’s front terrace, even at this late hour. She lets go of Audrey’s arm and dances a few jazz steps in the street, then turns back to face Audrey.

‘They say this place makes the only genuine cappuccino in town. We’ve got to try one, Auds. What do you say?’

Audrey looks at her watch. She starts her new job in the morning but, equally, she doesn’t want to disappoint her friend. Janet has been so kind.

‘Umm,’ she says.

‘Come on! It’s only a coffee. Carpe diem!’ Janet grabs her arm again. ‘I still can’t believe you’re here! And we’ll be working together from tomorrow! Don’t worry! I’ll look after you!’

‘Okay, just one, though. A quick one.’

Audrey allows herself to be drawn towards the café. She still remembers the mix of shock and delight on Janet’s face when she’d turned up unannounced at the address given on the aerogramme. Aside from her visits to the church, her first few weeks in Bombay are a blur. Until very recently Audrey’s still had moments when she wakes up in the morning not knowing where she is nor why; mornings when she wakes expecting to be in her bedroom in London, then realises with a jolt that she’s on the other side of the world. She still has mornings when the grief is too raw, too painful, and she’s capable of doing nothing but lying, numbly, under the sheet, where Janet finds her when she comes home from work. But, in the last few weeks, the fog has started to lift and Audrey’s beginning to realise that she feels an affinity with the crazy, chaotic, noisy city that is Bombay.

The two women walk into the café and seat themselves at an empty table. Janet looks at Audrey and smiles.

‘I know I’ve said it a million times, but I’m so glad you came,’ she says. ‘It’s done you good. You look human now, compared to the ghost who turned up at my door.’

‘Thank you,’ says Audrey. ‘You’ve been amazing. I don’t know what I’d have done without you.’ She smiles at her friend. ‘But I do still feel a bit lost.’

‘Of course you do.’

Audrey’s eyes suddenly fill with tears. It happens at the most inopportune moments – times when something reminds her of her dad: a smell, a sound, the shape of a person, a voice. She can neither predict nor control it.

‘I’m so sorry,’ she says, dabbing at her eyes with the fresh hankie she keeps on her at all times. It’s one of her mother’s: good cotton, with a bright flower embroidered in one corner and, as Audrey lifts it to her eyes, she sees her mum tying it around her little knee to stem the blood after she’d fallen in the park.

‘Your dad was the best,’ says Janet gently. Audrey nods. Although it’s painful, especially to hear him mentioned in the past tense, she likes that Janet knew him; likes that she can talk to her about him.

‘Ignore me,’ Audrey says, flapping her hand at her face. ‘I’m okay. He was the best, wasn’t he? I’m not just being biased.’

‘I was always jealous of you and your dad,’ says Janet. ‘I know you missed your mum, but you seemed so happy. It’s like he was the captain of the Bailey ship, always sailing forward with his eyes on the horizon. I loved that.’

‘Me too. He was my rock.’ Audrey smiles through her tears.

Janet reaches out and touches Audrey’s hand. ‘And that’s how you must remember him.’

‘I do. I will. Thank you.’

‘My family was such a shambles.’

Audrey got her tears under control. ‘Don’t do them down,’ she says. ‘I used to love coming to yours. There was always that bowl of sweets on the hall table. I always nicked one. We never had sweets at home.’

Janet laughs. ‘Oh yes. The Murray Mints! God, I can still taste them!’ They fall silent as the waitress brings over their coffees. Janet looks at the froth on the cups and raises her eyebrows at Audrey. ‘Look at that: the real deal. Apparently they’ve got a huge machine just to froth the milk.’

‘Cool beans,’ says Audrey, and they each take a sip, delicately dabbing the foam from their top lips. ‘Very nice. Good call.’

With the buzz and the music in the café, it was never going to be just one coffee. As Janet and Audrey stir their second round of cappuccinos an hour or so later, Janet looks around the terrace.

‘So many men,’ she breathes, hamming it up for Audrey. ‘So little time.’

Audrey smiles. Janet’s never hidden the fact that she’s on a mission to find a wealthy husband; she has told Audrey about some of the scrapes into which she’s got herself, the frogs that she’s kissed as she searches for ‘the one’.

‘You should try to find someone, too,’ Janet says. ‘We’re not spring chickens anymore. We’ll be twenty-seven this year. The shelf is looming! Maybe a husband is just what you need.’

Audrey sighs. ‘If it’s meant to happen, it’ll happen …’

‘I don’t know how you can be so relaxed about it!’

‘Well … you know I used to be engaged?’ Audrey’s tone is mild.

‘What?’ Janet presses her hand to her chest and gasps as if she’s having a heart attack, her eyes wide. ‘How did you keep this from me for so long?’

Audrey laughs. ‘I guess we had more important things to talk about.’

‘I guess – but engaged?’ Her eyes slide to Audrey’s left hand, then back to her face. ‘Did you get married?’

Audrey shakes her head.

‘What happened?’

‘He wasn’t the right man for me.’

‘Um, would you care to elaborate on that?’

‘It’s quite sad, actually. I thought he was lovely. A real catch. He was Irish. Patrick. Loved the ground I walked on. Or so I thought.’

‘I feel a “but” coming on.’

‘Well, it was quite simple in the end: when Dad had his first stroke and it became apparent that I’d need to move back home to take care of him, he dumped me.’

‘What?’

‘I suggested we move the wedding back a bit but he kept pushing for a date and I couldn’t commit. I didn’t know how long I was going to be needed at home – so he called the whole thing off.’

‘Couldn’t you have been married but live at home with your dad? Loads of people do that to start with. Surely?’

‘You would have thought so, wouldn’t you, but apparently not. “No wife of mine’s living with her father,” he said. I do understand.’

‘I can imagine your dad being quite foreboding towards his daughter’s fiancé.’

‘He never liked Patrick. Didn’t think he was good enough for me.’

‘Find me a man who doesn’t think that about his only daughter and I’ll show you a liar.’

‘I guess. But it seems he was right. Better to find out before it’s too late.’ Audrey sighs and looks about the terrace, too. ‘So, anyone you’ve got your eye on here tonight?’

‘Funny you should mention it,’ says Janet, ‘but yes. Grey suit at three o’clock.’ Audrey follows her friend’s eyes and sees a tall man, classically attractive. He’s wearing a slick suit with a white tie, and his dark hair is greased back from a prominent forehead.

‘Not bad,’ she nods. ‘Looks the part.’ Audrey knows the rules. Janet’s marriage will not be about love, but about money. Janet’s seen the society ladies with their jewels and their dresses being escorted by men in black tie, she’s seen the cars with turbaned drivers waiting outside, and she’s decided that’s what she wants.

They watch the man in the grey suit for a minute or two. Audrey has to give it to her friend: he’s very handsome but there’s a sense of something else that almost makes her shiver and she can’t put her finger on what it is. As she watches, the man turns around; Audrey doesn’t look away in time and he stares back, openly assessing her.

Audrey drops her eyes to the table. It’s power, she realises. Power and confidence.

‘What do you think?’ Janet asks.

Audrey says nothing. The man in the grey suit is still watching them. With his eyes still on Audrey, he gets up and makes his way over. Janet pats her hair and rolls her lips together to spread her lipstick.

‘Good evening, ladies.’ Grey Suit towers above their table. Audrey can feel the heat of him, and something tugs in her belly.

He has sharp cheekbones and his small eyes are not only bright, they’re looking Audrey up and down in a way that makes her feel like she’s something he’d like to devour. She’s wearing a one-shouldered shift dress in vibrant pink. It’s a dress she made herself and she knows it shows off the delicate bones of her clavicle while the colour sets off her auburn hair, but now she feels unsure. Why is he staring? Has her mascara smudged from crying? Is the dress so obviously home-made? Is the colour too loud – or is he really leering quite so openly?

‘Ralph Templeton,’ he says, placing a business card on the table in front of Audrey. He doesn’t acknowledge Janet simpering across the table. ‘Perhaps you’d allow me to take you out to dinner one evening?’

‘Oh, I …’

The man looks at her while he waits for her to finish her sentence. He’s older – distinguished – and, under his gaze, Audrey feels girlish and lacking in substance. There’s no doubt about what it is he wants from her. She blushes and looks down, her sentence left hanging.

‘May I take your number?’ The man produces another business card and a pen. The cold weight of the pen tells Audrey it’s expensive. She balances it in her hand for a second, toying with the idea of writing the wrong number. But there’s something in Ralph Templeton’s demeanour that suggests that refusal is not an option and Audrey finds that confidence compelling. She doesn’t dare make eye contact with Janet as she writes her new office number on the back of the business card.

‘Thank you. I’ll have my assistant call you,’ says Ralph Templeton, picking up the card and slipping the pen back into his breast pocket. Then he reaches out his hand and touches Audrey’s hair.

‘Beautiful,’ he says. He runs a finger through a curl, then gently draws it down her cheek. He looks one more time at Audrey and melts back into the crowd. Janet’s hand is clamped over her mouth.

‘Oh my word! Talk about reeling them in! I need lessons from you!’

Audrey barely hears. She can just about make out the back of Ralph Templeton’s head as he re-joins his table, and she can’t tear her eyes away. Her cheek tingles where he’s touched it and her body is electrified. The physical pull of Audrey’s feeling towards Ralph Templeton takes her by surprise. She stares at the business card as if to memorise every tiny detail.

November 2012 (#ulink_fdf21f6e-356a-5859-8ec9-3c34f6ff7fad)

Truro (#ulink_fdf21f6e-356a-5859-8ec9-3c34f6ff7fad)

I was on the sofa with a cup of tea and a pile of marking when I heard Mark’s key in the lock. Within seconds, he appeared in the living room doorway, filling it completely with the bulk of his frame. I looked up at him feeling, as always, a surge of love for my husband and noting at the same time the flicker of hope in his eyes.

I dropped my gaze back to the marking, willing him to know I wasn’t pregnant without me having to spell it out. Mark crossed the stripped floorboards in three strides and bent down to drop a kiss on my hair, his fingers stroking my cheek as he did so. He dropped onto the sofa next to me. His hand found mine and he interlaced our fingers.

‘Hi darling,’ he said, giving my hand a squeeze. ‘How was your morning?’

I squeezed back.

‘Did you hear from the doctor?’ Mark asked, his face alive with expectation.

I turned to look at him, pressing my lips together, and nodded slowly, unable to articulate the words. Mark pulled me against his chest with his free arm. I felt my eyes well up; a prickling at the back of my nose. I squeezed my eyes shut and tears spilled onto Mark’s sweater.

‘It’s okay,’ he said, rubbing my back. ‘It’s okay.’

I pulled away and looked stared at his face in despair. ‘But it’s not okay! How is it okay? How can it possibly be okay? I was so sure this time! I’m getting older. It’s not going to happen!’

‘Lex. Lex, Lex, Lex. We’ve been through this. Yes, a baby would be nice, but we have each other. It’s enough. It’s you I married, not a child who doesn’t yet exist. It’s you I want.’ His voice cracked. ‘I wish you would believe me.’

I closed my eyes. ‘I know you mean it now. But what happens in five years? What if you change your mind? You can …’ I didn’t say it. I’d said it before; Mark could leave me and have a baby with someone younger. It was my deepest fear; that I wouldn’t be able to give him what he wanted and he’d leave.

‘That’s not going to happen. You’ve got to stop beating yourself up about this, Lex. Please.’

I knew he was right and I did believe him. It was my guilt that kept bringing me back to this place: guilt that I’d wasted my child-bearing years in a dead-end marriage with a bully of a husband; guilt that I’d been too scared to leave. If I’d walked away five years sooner – if I’d met Mark five years earlier – maybe we’d have a nursery upstairs; the sound of tiny feet pattering overhead. It was a train of thought that Mark consistently refused to entertain. ‘Everything happens for a reason,’ he’d say. ‘Maybe I’d have been a bastard to you five years ago. You can’t live life thinking “if only”.’

I sat back up and wiped my eyes with the back of my hand. The baby conversation – the same hopeless one we had every month – was going nowhere. ‘Mum had a car accident last night,’ I said. ‘John called to tell me. It’s not been a good day.’

‘Whoah, sweetheart. What happened? Is she okay?’

‘I think so. Bumped and bruised but nothing broken. She’s shocked and might have whiplash but they’ve discharged her on condition someone stays with her overnight. John’s asked me to go.’

‘Okay.’

I sighed. ‘It’s just … with all this …’I flicked a hand over my abdomen, ‘I just …’ My face crumpled again.

‘I know, sweetheart. I know. But it’s your mum, and she needs you.’

‘I wish John could do it.’

‘Have you told him about … you know? Does he know we’re trying?’

I shook my head.

‘Well, then you can’t expect him to be sympathetic, hon.’

‘I know, but …’

Mark looked at the floor. I knew him well enough to know he was trying to compose a sentence that I wouldn’t necessarily like in terms that he hoped I might accept.

‘He can’t always be there for your mum, Lex. He’s got a family,’ Mark said carefully. He held up his hand, anticipating my argument. ‘Yes, I know the twins aren’t his. But Lexi, you’ve got to get over this. He’s married their mother and adopted them. They are his responsibility now.’ Mark paused to check he still had my attention. ‘And we both know it’s the prima donna who wears the trousers in that marriage.’ He smiled at me. ‘When she says “plié”, he pliés over the bloody moon and back!’ I couldn’t help but crack a smile at the image of my po-faced brother flying over the moon in a ballet tutu. ‘His life is way more complicated than ours, sweetheart. He’s being torn in so many directions.’

I sighed and picked imaginary fluff off the arm of the sofa.

‘And this is why we live here,’ Mark continued. ‘So you can help out. Can you imagine if you had to come down from London? It’s so much easier now.’ He paused and I didn’t say anything. ‘Shall I help you pack?’

‘It’s okay. Thanks. I’ve already put some stuff in a bag.’

‘Good. Anyway – I have some good news today.’

‘Really? What?’

‘Fanfare please!’ Mark pretended to play a trumpet. ‘I should have a payment coming in this week!’

‘Really? A big one?’

He nodded. ‘Yep. It won’t do anything daft like buy a car, but it should cover our outgoings for a couple of months. Give us a bit of a breather.’

Even as he said the words, I felt the tension I’d been carrying since we’d realised that it wasn’t going to be as easy as we’d hoped for Mark to find a job in Truro release a notch. For the past few months, we’d been living hand-to-mouth on my teacher’s salary, which barely covered the mortgage payments, plus the few odd jobs that Mark could do.

‘That’s fantastic.’

Mark smiled. ‘And there’s more. I’ve got a lead on a job that looks promising.’

‘Wow! It’d be so good to have you back on a regular salary.’

‘Tell me about it.’ Mark leaned over and kissed me. ‘Now. What else can I fix for you today, madam? Burst water pipe? Faulty boiler?’

I nodded my head towards the marking. ‘Do you feel like marking eighty Year 6 assessments while I’m away?’

‘I can’t help you with that, I’m afraid: you’re the smarty pants. Why don’t you take them to your mum’s? You’re bound to get a chance to do it there.’ He paused. ‘But, please, darling, please don’t make her feel bad about you going down.’ He lifted my chin with his finger. ‘I know what a little martyr you can be.’

March 1971 (#ulink_0838be95-0f70-5a1d-a47a-9a5439cae766)

Bombay, India (#ulink_0838be95-0f70-5a1d-a47a-9a5439cae766)

Audrey’s new job is in the office of the shipping firm where Janet works. She’s far too busy on the first day, meeting the other staff and learning the ropes, to think about Ralph Templeton. But, as she starts to settle in over the next few days – as she answers the phone, types the invoices, and franks the mail – she finds her thoughts returning to the handsome stranger who’d taken her number, and she’s surprised to realise that she’s hoping he’ll telephone.

‘How about we go back to that jazz café tomorrow after work?’ she says to Janet as they chat over their hot tiffins in the tea room almost a full week after their night out. She traces her finger over the Formica countertop that’s stained with rings from mugs of tea. The smell of old cigarette smoke hangs in the air and a ceiling fan circles lazily overhead.

‘Sounds like a plan,’ says Janet. ‘Any particular reason why?’ She raises an eyebrow at Audrey.

Audrey focuses on her dal bhat, the simple dish of spiced lentils and rice that she’s come to love. ‘I thought the cappuccinos were amazing.’

‘Just the cappuccinos?’

‘Yes, just the cappuccinos.’

‘Because I suspect there’s another reason you want to go back. A tall, handsome reason in a grey suit, perchance?’

Audrey feels heat rush to her cheeks. She licks her spoon and, once she decides to talk, finds that the words spill out of her. ‘Okay. Maybe you’re right. You have to admit, there was something about him. But it’s not that I want to see him. I just want to know why he hasn’t called. I mean, why make the effort to come over and give me his card and get my number if he’s not going to call?’

‘Oooh!’ teases Janet. ‘I do believe the lady’s got her knickers in a twist!’

‘I have not!’ Audrey flicks a piece of chapatti at Janet. ‘It’s just – why did he ask if he’s not going to call? Do you think I gave him the wrong number by accident? I’ve gone over it a hundred times.’

‘No. I saw what you wrote. It was right.’

‘Well, what then? Do you think it was a dare? Or did I say something wrong?’

‘No, no. It’s not you,’ says Janet. ‘He’s just a chancer. Probably got a better offer. Sorry. Ignore it. Move on.’

‘Whatever you do, don’t tell me there are plenty more fish in the sea!’

‘Well, there are. It’s just that maybe we’re not fishing hard enough.’

‘I’m not fishing at all. I’m hoping the right fish will offer itself up on a plate for me when the time’s right. With chips and dill mayonnaise!’

‘So romantic! But, Auds, we’re twenty-seven. I hate to tell you, but the fish are offering themselves to girls a lot younger than us. To some men, an unmarried twenty-seven-year-old is a scary proposition. We’re going to be thirty soon. Thirty! They imagine all we want to do is tie them down and get ourselves pregnant.’

‘Seriously?’

‘’Fraid so. I’ve heard it from guys. Sometimes I pretend to be twenty-three because, as soon as they find out how old I am, they run a mile. I worry about it. I worry that I’ll never meet the right one. That I’ll be a mad old spinster with only cats for company.’

Audrey skims off the fine skin that’s formed on her chai, then breathes in its comforting scent of cardamom and cloves. ‘There’s nothing wrong with that from where I’m sitting. It beats sitting around waiting for the phone to ring.’

Ralph Templeton eventually calls. But not on the phone. When Audrey and Janet step out of the office on Friday evening a week later, there’s a grey Daimler parked outside, a crowd of beggars teeming around it, pawing at its sleek paintwork and tapping at its windows. As Audrey approaches, the back door of the car opens and Ralph Templeton climbs out, a bouquet of brightly coloured flowers in his hand. His suit is immaculate and there’s something commanding about him as he straightens up to his full height. Filthy street children scatter out of his way.

‘Miss Bailey,’ he says, holding out the flowers. ‘I wondered if you’d do me the honour of accompanying me to dinner tonight?’

It takes Audrey a second or two to understand that Ralph Templeton is here in person, to ask her out to dinner.

‘Tonight?’ she says. She looks down at her clothing, more office than night out. ‘It’s just I … I’m not …’

‘You look beautiful,’ says Ralph. ‘But if it makes you feel better, I took the liberty of choosing a few dresses. They’re in the car. You could pick one and change at the hotel.’ He lets this sink in. ‘I have a dinner reservation at the Taj.’

Audrey looks at Janet. Janet widens her eyes. ‘Fish,’ she mouths, and Audrey turns back to Ralph, bobbing her head as she replies, ‘Yes please. I’d be delighted to join you. Thank you.’

Ralph opens the car door wide once more. ‘After you,’ he says.

April 1971 (#ulink_176c89f7-2406-5ee6-ac71-4e60fcf816e2)

Bombay, India (#ulink_176c89f7-2406-5ee6-ac71-4e60fcf816e2)

On the back seat of his Daimler, Ralph Templeton puts his arm around Audrey and pulls her close to him. She breathes in the now-familiar scent of his cologne and rests her head against his chest. He strokes her hair almost absently, letting it twine itself around his fingers, and Audrey sighs, her mind full of images of this man – this stranger – who’s shot into her life like a bolt of lightning. Was their first date really just three weeks ago?

Audrey feels her cheeks flush as she remembers the way Ralph had devoured her with his eyes over dinner that evening; the way his gaze had made her feel so gauche despite the expensive dress she’d picked. Maybe she is a little younger, less sophisticated, than the women Ralph’s used to, but he seems charmed by that. She bites her lip: thinking back, she can’t believe she’d actually given him a real phone number in the café instead of transposing a couple of digits like she usually did when men pushed for her number; she can’t believe she’d agreed to go out to dinner that night he’d turned up at her office. How life turns in an instant, she thinks.

After their first date, Ralph had bundled her onto the back seat of his Daimler and nuzzled her face until his lips found hers, then he’d kissed her all the way back to her tiny studio flat. Despite his protests, she’d refused to let him in. It’d been the right strategy, Audrey reflects now, because he hasn’t been able to get enough of her since, pursuing her with a fervour that almost verges on the indecent.

In the car now, Ralph’s hand moves from Audrey’s hair to her cheek. Applying a little pressure, he turns her face to his, stares into her eyes as if he’s searching her soul, then places his lips gently on hers, the softest of kisses that melts her. When he finally pulls away, she’s breathless.

‘Come home with me tonight, Red,’ he says.

Audrey notices, all of a sudden, that the car’s not on the usual route to her flat and a ripple of fear runs through her. She’s in the back of a car with a man she’s known less than four weeks, in a part of Bombay with which she’s unfamiliar. No one in the world bar Ralph Templeton and his chauffeur knows where she is.

‘Where are we?’ she asks, sitting up straight in her seat and trying to get her bearings.

Ralph takes her hand. ‘On the way to Juhu. I asked the driver to … please, Red. Come home with me.’

Audrey buys time by fiddling in her handbag. Does she have reason to be afraid?

‘Look at me,’ Ralph commands. He takes her chin into his hand, turns her face to his and stares into her eyes. Audrey holds his gaze, mesmerised by the apparent depth of her suitor’s feeling. ‘Nothing will happen, not if you don’t want it to,’ Ralph says. ‘This is not about sex. But please come home with me. I just want to have you there with me. To hold you.’ His voice breaks. ‘Red, I need you.’

He lets go of her face and turns away, his hand brushing at his eye and the very core of Audrey melts. There’s something about this man that makes her feel she’d run to the end of the earth if he asked her to. She leans across and places her lips on Ralph’s ear.

‘Okay,’ she whispers.

November, 2012 (#ulink_b61ac1f3-c55d-5fb3-b945-255d7afb0b25)

St Ives, Cornwall (#ulink_b61ac1f3-c55d-5fb3-b945-255d7afb0b25)

To say that John and I were surprised when Mum left London for Cornwall would be one thing; what was even more of a surprise was the house that she’d bought on the outskirts of St Ives. The large, stucco-fronted villa we’d grown up in in Barnes had been built in 1845. After selling it four years ago when our father died – far too quickly because she’d under-priced it, if you listened to my brother – Mum had eschewed the type of picturesque stone cottage we’d all envisioned she’d go for and bought a completely unremarkable box of a home that dated back to the seventies.

Moving with a speed and certainty that had taken us by surprise, Mum had allowed us each to choose any furniture we wanted from the Barnes house, then made the move to St Ives. ‘It’s got a subtropical microclimate,’ she’d told anyone who asked her why she was moving there. ‘Why wouldn’t you?’ There was also, I suppose, the fact that John lived in nearby Penzance, though I’d long suspected that was more coincidence than intent.

I took in Mum’s house now as I parked behind her car in the driveway, gathered my things, and made my way down the steep slope to the front door. It was a low building, painted white, with double glazed windows and a neat front garden that Mum had lined with geraniums in pots. They added a certain something in summer, but not quite enough.

The rain had cleared but I still heard the irregular plop of drops falling off the trees and bushes. The garden was saturated. I knocked on the front door: two smart raps of a silver-toned knocker that made a hollow sound on the thin door. While I waited, ears straining for the sound of footsteps, I bent down and examined the front step. I’d noticed a while back that a brick had come loose and was wobbly to stand on. I’d asked John to cement it back down. He hadn’t: the step still wobbled. I straightened up again, put my finger on the doorbell and pressed. Big Ben rang out electronically and I cringed inside, remembering both the substantial door and the majestic ring of the bell on the house in Barnes. After waiting another moment, I realised that Mum might not even be able to make it to the door. Kicking myself for being so stupid, I walked around the side of the house for the spare key, my shoes squelching on the wet gravel path.

I paused for a moment on the threshold of the garden. It was around the back that Mum’s house came into its own: by itself, the small garden was unremarkable – it was only once I’d seen the view that I understood why Mum had fallen in love with the house. I drank in the view now: the sandy reach of Carbis Bay lay below and, curving into the distance, I could see Lelant and subsequent coves: the scalloped edge of England. Even on a dismal November day it was something really special. Today the sea looked grey-green but, in summer, it was an endless sweep of azure blue that was more Mediterranean than Atlantic. The previous owner of the house had installed decking that wrapped around the sea-facing aspects. Mum had bought some nice outdoor furniture and she claimed to spend part of every day out there, no matter what the weather. My city-dwelling mum, it turned out, loved the sea.

I scrabbled under another plant pot for the spare key, then let myself in the front door, dropping my bags and slipping off my wet shoes in the hall before padding quietly into the living room. Mum was on the sofa, propped up on a pile of cushions, her laptop open on her lap. She looked fragile, her face as pale as the brace that circled her neck, but, aside from that, I could see no physical evidence of an injury; no bruising, no extra bandages. I walked across the room to her and looked down at her. I couldn’t tell if she was asleep or awake.

‘Mum?’ I asked softly.

She slowly lifted her eyes to meet mine. ‘Alexandra. Hello! How lovely to see you. You really didn’t need to come.’ She tapped the mousepad a couple of times, then closed the lid of the laptop.

I perched on the edge of the sofa and looked at her. ‘Of course I was going to come. John said someone had to stay with you and it was my turn. How are you feeling?’

Mum touched the neck brace. ‘I’m fine.’ I raised my eyebrows at her. ‘Really, I am. This is just a precaution. In fact, I’ve got to go back tomorrow and have it taken off. They’re just playing it safe.’ She gave me a bright smile. ‘It looks worse than it is. I promise you I’m absolutely fine or they wouldn’t have let me out.’

‘I’ll take you in tomorrow.’

Mum nodded. ‘Thank you.’

‘You’re welcome. You look a bit pale, but I suppose that’s the shock. Are you in pain?’

‘No.’

‘Mum. Don’t lie.’

She sighed. ‘Okay, well, maybe just a little. It aches a bit, that’s all. I feel as if I’ve been knocked about a bit in a road accident.’ She laughed.

‘Mother! This is a serious thing. At your age! You’re so lucky nothing was broken. What happened?’ I tutted. ‘I should never have let you drive back last night. Were you tired? You didn’t seem tired.’

Mum didn’t reply. She was staring at the wall, then she turned to look at me.

‘Was I a good mother?’ she asked. ‘To you and John?’

I leaned back on the sofa. ‘Whoah! Where did that come from?’

‘I just wondered,’ Mum’s hands fretted at the fringe of the sofa blanket. ‘Seeing those pictures last night … it brought it all back. My time in India … when you were babies … coming back to London.’ Her voice trailed off. ‘Did you feel loved as you were growing up?’

I hesitated – a whisper of a moment – but Mum appeared not to notice. ‘Yes, of course,’ I said. ‘We never wanted for anything.’

And it was true – to an extent. Mum had done everything by the book when John and I were growing up. It was as if she’d read a manual on how to be the perfect mother. She cooked and cleaned and picked us up from school; she sewed, helped us with our homework, and took us to the park – but I’d always felt as if she’d wrapped her heart in cling film. I’d always felt it was as if, when I hugged her, I wasn’t ever touching the real her; as if there was always something of herself that she held back.

‘But …’ Mum looked at me so intently I felt she could see what I was thinking.

‘But what? What’s all this about?’ I asked. ‘Are you worried we’ve turned out badly?’ I laughed.

‘No. No, it’s nothing. Forget I spoke.’ Mum shook her head and gazed off into the middle distance.

I stared at the carpet. Mum and I never had conversations like this. ‘So what happened?’ I said finally. ‘The accident? Was it because you were tired?’

She looked at me as if only just realising I was in the room. ‘Oh! No. No, I was fine … I stopped at a roundabout and some clown drove into the back of me. It wasn’t my fault.’

‘Is that what the police said?’

Again Mum didn’t reply. She was staring at her hands, examining her fingers.

‘So – did you stop suddenly or something? At the roundabout?’

‘What?’ said Mum.

‘Did you stop suddenly?’

‘Oh, yes. Yes. I was approaching the big roundabout near home. You know the one? I was about to enter it and then I don’t know what happened. Someone came flying around. I don’t know where he came from. I suddenly saw him. I braked but the guy behind didn’t stop in time.’

‘So he rear-ended you?’

‘Yep.’

I imagined Mum’s head whipping forward and back. ‘Okay, well. If he rear-ended you, it’s his fault.’

‘Yes, that’s what the police said.’

‘Good. And it’s good they put you in the brace. At least for tonight. I’m glad you’re okay.’ I stood up and stretched, bending my neck left and right. The traffic down to St Ives had been stop-start the whole way and my shoulders ached. ‘Can I get you anything? Have you eaten? I’m going to make myself a cup of tea and, if you don’t mind, I’ve brought some marking to do. If I don’t do it tonight, I’ll be in trouble.’

There was a silence. I looked at Mum – she was staring off into the distance again. I felt for my phone, thinking I must text John about this. He was right. Mum was clearly not herself. Whether or not this was related to the accident I had no idea. I was ashamed to realise I hadn’t been down to see her for over two months.

‘Mum? Would you like anything? Some tea?’

Mum gave herself a little shake. ‘Yes, thank you. A cup of tea would be lovely.’

‘And what about food? Shall I get some stuff in for you? Easy things for your dinners?’

‘Oh, no need for that, dear! I’ll be right as rain in a day or two.’

‘But – I don’t know. Should you be driving? Carrying heavy bags? Wouldn’t it be easier if I nipped out and got you some bits that you could just bung in the microwave for this week?’

‘I’m not helpless.’

‘No, I know. But can you please just admit it would be easier if I got you some ready meals? You can get good ones these days. Fresh. Almost like home cooking.’

Mum bowed her head. ‘Thank you.’

‘Okay. So what do you like? Curries? Indian? Thai? “Chicken or beef”?’ I smiled like cabin crew.

‘A shepherd’s pie would be nice, maybe. And, yes, why not a curry or two? Spicy, thank you, dear.’

‘Do you need anything else while I’m there?’

Mum shook her head.

‘How about milk? You’ve got eggs. You could make an omelette one night?’

‘Oh yes. Maybe some milk. To see me through. Thank you. And I think I’m low on cheese.’

I smiled. ‘Back in a bit.’

‘Thanks, dear.’

As I headed to the front door, I looked back at Mum and immediately wished I hadn’t: lying on the sofa in her neck brace she looked small, and so very frail.

Back in the car I texted John. ‘You’re right. She’s not herself. V vague. Gazing into distance.’

He texted back at once. ‘Told you.’

‘But is this the accident? Or was she like this anyway? I don’t remember.’ I put the blushing Emoji.

‘Bit of both. She’s getting old.’

‘70 next year.’

‘I know.’

July 1971 (#ulink_9bf89f63-d33d-5155-b5d1-b55b1928db74)

Bombay, India (#ulink_9bf89f63-d33d-5155-b5d1-b55b1928db74)

‘You’ve changed.’ Janet taps her teaspoon on the saucer of her coffee cup and looks thoughtfully at Audrey across the table. They’re once again in the jazz café – it’s become their regular post-supper haunt, with Janet making no secret of the fact she hopes that she, too, will meet her own rich lover among the clientele.

‘In a good way, I hope!’ Audrey laughs, but even she hears the question in her voice. She lifts her cup to her lips and takes a tiny sip.

Janet pouts thoughtfully. ‘You’re more confident.’

‘That’s a good thing, isn’t it?’

‘Yes. Yes, of course. And you look amazing. You’re glowing.’

It’s the sex, Audrey thinks. She looks at her coffee. ‘Well, I do feel better than I have in months. Years! Oh Janet, he’s the best thing ever to have happened to me. Honestly, I always used to think how could so many terrible things happen to me – surely it was my turn to have some good luck – and along came Ralph!’

‘I’m so glad you’re happy,’ Janet says, but Audrey sees a hardness in her friend’s eyes. She looks at her closely; it’s not jealousy – it’s something else.

‘Thank you,’ she says. ‘He’s just so …’ Audrey waves her hand in the air, struggling to articulate how she feels about Ralph – how different he is; how her love for him consumes her. ‘I don’t know: perfect?’

Janet touches Audrey’s hand. ‘Just be careful. All right?’

‘What do you mean “careful”? I’m on the Pill.’

Janet tuts. ‘Not that kind of careful. Well – that kind of careful too. Just don’t lose yourself in all this.’ She stops talking but Audrey doesn’t reply. ‘It’s just – there’s something about him. I don’t know.’

‘Something about him? Looks, personality, charm – where do I start?’ Audrey tinkles a laugh.

‘Not like that. I mean, he’s too good to be true. Men like him just don’t exist. Trust me, I’ve a lot of experience.’ Janet gives a rueful laugh.

‘But he does exist, and he really is that good. I’ve been to his house. Many times. What you see is what you get with Ralph.’ Audrey looks around the café, keen to change the subject now it’s taken this turn. ‘Look! Did you see that chap over there? What a dreamboat …’

Janet gives a cursory glance then turns back to Audrey. ‘Men like Ralph Templeton … they usually have something to hide,’ she says. ‘Really, Auds. I’m shure there’s something he’s not telling you.’

Audrey sucks her teeth and stares at her friend. The noise of the café behind her – the sounds of conversation, laughter and jazz – falls away as she realises that she’s at a crossroads in her life; that this conversation is somehow seminal – something she’ll look back on in years to come. She badly wants her friend’s approval but she knows, too, that her relationship with Ralph is bigger than her friendship with Janet will ever be, and that, should she be forced to choose, her lover will be the one who’ll win.

Audrey sighs. How can she explain to Janet what it is that Ralph Templeton does for her? How could she explain what it feels like to have no one in the world who loves her? How she misses having her father there to keep everything under control, and to offer advice and comfort? Would Janet understand if she told her how her insides know an emptiness that goes beyond life itself? Ralph Templeton is her antidote; he fills her veins with hot, red blood; he brings life back to her. Janet herself has noticed how Audrey’s changed – blossomed – since she got together with him. And on top of that, he’s so knowing, so worldly wise, so confident – he fills a little of the gap that yawns inside her. Just thinking about Ralph makes her shiver with anticipation of when she’ll next see him.

‘He takes such good care of me,’ she says.

‘That’s nice,’ Janet’s voice is sarcastic. ‘But don’t you find him controlling? The way he calls you “Red”?’ She shudders and Audrey recoils: her dad had called her mum ‘Mousie’ and she’d always thought it was sweet. But Janet is on a roll. ‘The way you always do what he wants? You never get to choose where you go or what you do. The way he drove you to his house without asking you till you were right outside? Even the way he came over demanding your number that day. It’s like he won’t take no for an answer.’

‘I quite like that,’ Audrey says.

‘You want to be careful, though.’ Janet points her finger at Audrey. ‘One day controlling, the next you’re not allowed out. It’s almost like he sees you as a possession.’ She shakes her head. ‘The way he sends his car to pick you up all the time. My word!’

Audrey closes her eyes and recalls the cool, leather interior of the Daimler. It’s nice that Ralph sends the car for her. Especially when the rain’s throwing it down as it has been this month. Really, she has no problem with that.

15 July 1971 (#ulink_bc1e7330-db0d-5c22-8811-6800f27ba858)

Bombay, India (#ulink_bc1e7330-db0d-5c22-8811-6800f27ba858)

Audrey’s grateful that the driver Ralph’s sent to pick her up for her birthday dinner isn’t one of the chatty ones. The drive to the Taj Mahal Palace is a long one and she turns her head and stares out of the window, watching as the car passes through the teeming street life of Bombay.

She watches beggars, cripples, cyclists, cars driving four abreast on what should be a three-lane road; sees pedestrians throwing themselves into the teeming traffic with little regard for life or limb. Whenever the car stops – which it does frequently given the road is permanently choked with traffic – filthy children swarm the windows, their hands tapping at the glass, thumbs rubbing against fingers as they beg for a coin, a bite to eat, something, anything. It’s rained heavily and the car cleaves through standing water; the beggars are up to their ankles in it, but Audrey shakes her head at them and looks away, as she’s learned to do. It’s not that she doesn’t see the scrum of life outside the car; it’s not that she doesn’t feel sorry for the beggars – rather that she accepts it, understands that it’s part and parcel of life here. England seems so very distant these days. She can barely remember what life was like there. Cold. Ordered. Lots of rules and a place for everything.

She can barely remember life before Ralph, either. Audrey sits back in her seat and smiles to herself as she thinks about the nights she’s started spending in his sprawling villa on Juhu Beach – nights in which she’s slept with his arms wrapped tightly around her, her heart brimming with a love like she’s never known as the rain drums down on the roof. It’s as if heaven has sent the perfect man for her and, again, she wonders if her dad somehow had a hand in it.

‘I’m so glad you found me,’ she tells Ralph in bed as she strokes her fingers across his chest and drops butterfly kisses on his arm. ‘That day – when you saw me. You came over to Janet and me so decisively. It was as if you knew what you wanted.’ She shivers at the memory. ‘Did you just “know”?’

‘Yes,’ Ralph says. ‘I watched you for a while. I watched you talking to your friend and I saw something in you that made me want to protect you forever.’

Audrey wonders where it’s all heading. She’s allowed herself to dream about a future with Ralph; about carving a permanent life in Bombay, and she’s surprised to find she’s happy at the thought of it. Here, in India, there’s a contentment in her soul that she doesn’t remember feeling in England. Part of it, she’s sure, comes from her regular trips to the church, where she sits silently in a pew and holds silent conversations with her father.

The driver pulls into the hotel’s driveway and the car comes to a standstill adjacent to the front steps. Audrey pulls some notes from her purse and offers them a tip. The driver steeples his hands to his chest, nodding his thanks to her, and the hotel’s doorman opens the car door and wafts Audrey up the steps to the Taj’s impressive interior.

‘I’ve something to tell you.’ Ralph reaches across the table and takes Audrey’s hand in his.

‘Yes?’ She looks expectantly at him. The waiter’s taken their orders and they’re sitting with their drinks. Ralph looks down at Audrey’s hand and strokes it. Then he looks up at her with such a depth of emotion behind his eyes that she has to swallow.

‘Red. I care about you very much. I need you. I need you in my life.’ He pauses. ‘But there’s something I have to tell you.’

Audrey’s blood runs cold. If her hand wasn’t clasped in Ralph’s she’d snatch it back. Janet’s words come back to her: he’smarried, she thinks, and tears prick behind her eyes. With her free hand, she dabs at her eyelashes, her lips trembling as she tries not to cry. What a chump she’s been to think a man like him would be seriously interested in the likes of her.

‘No, don’t. Don’t tell me,’ she whispers. ‘I don’t want to know.’

‘Please. I have to tell you.’

Is that the beginning of a smile on Ralph’s lips? Audrey stares at the tablecloth and waits. Waits to hear what a fool she’s been. Waits to hear about the delicate wife he doesn’t love but can’t leave; waits to have her birthday dinner ruined.

‘You don’t know who I am, do you?’ Ralph asks. He doesn’t wait for a reply. ‘You didn’t see the story in the papers?’

Audrey shakes her head.

‘I used to be married,’ says Ralph. Used to! Audrey looks up, barely daring to meet his eyes but he carries on before she can say anything. She watches his lips – those lips she loves to kiss – as he speaks. ‘Alice – my wife – died.’

Audrey’s gasp is too loud. There’s a stir in the restaurant as other diners look over. ‘I’m so sorry!’

Ralph, oblivious to the attention, looks at the tablecloth for a minute, takes a deep breath; continues. ‘She … she was swept out to sea. They think it was a suicide. It looked like suicide. She couldn’t swim. She walked into the sea deliberately. She left her clothes on the shore – as a clue, perhaps, because … why else would she take them off if she was planning …’ His voice falters.

‘I’m so, so sorry.’

Ralph lowers his eyes and nods his acceptance of her sympathy. He sits back and breathes deeply and Audrey has the sense that the world is tilting. ‘They think she had postnatal depression,’ Ralph says. ‘We had children, Audrey. Twins. John and Alexandra. They were three months old at the time.’ Audrey covers her mouth with her hand.

‘No, no! Those poor babies.’ She shakes her head vigorously, feeling pain for the babies she doesn’t know. And then a thought strikes her: ‘But where do they live, the twins? When I stay over at your house, where are they?’

‘They live with me in the house. But I’m often out so they have an ayah – a nanny. Their nursery is close to the ayah’s room. You won’t have heard anything from upstairs.’