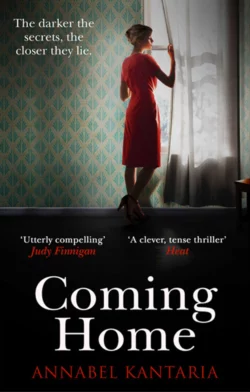

Coming Home: A compelling novel with a shocking twist

Annabel Kantaria

An ordinary family. A devastating betrayal.‘An utterly compelling story of loss and betrayal – I loved it’ – Judy FinniganEvie has been away from home long enough to bury the pain that shaped her childhood.Now, with the sudden death of her father, she must return. Back to the same house. Back to the memories. Back to her mother.At first, coming home feels unexpectedly comforting. But, as she goes through her father’s files, Evie uncovers a secret that opens old wounds and changes her life forever.That’s only the beginning. As Evie’s world starts to shatter around her, she realises that those she loves most are also those capable of the deepest betrayal.A powerful, poignant novel, Coming Home is perfect for fans of Jodi Picoult and Liane Moriarty. Praise for Annabel Kantaria‘An utterly compelling story of loss and betrayal – I loved it’ – Judy Finnigan'A gripping debut. You won’t be able to turn the pages quick enough.' - Bella magazine‘Compelling … fans of Jodi Picoult and Liane Moriarty will enjoy this powerful new book’ - Candis' clever, tense thriller about a family falling apart' - Heat

Born in 1971, ANNABEL KANTARIA is a British journalist who’s written prolifically for publications throughout the Middle East. She’s been The Telegraph’s ‘Expat’ blogger since 2010 and lives in Dubai with her husband and two children. Coming Home is her first novel.

Coming

Home

Annabel Kantaria

For Mum

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#u8c3d63fe-b438-5f9f-8b08-3bf9eb9fcbb8)

It’s taken the support of many to get this book to publication.

My deepest thanks go to my brilliant and patient agent, Luigi Bonomi, who picked my manuscript as a winner and offered his unwavering support at every turn, and to Alison Bonomi for her nurturing support and spot-on editorial advice.

Enormous thanks to the Emirates Airline Festival of Literature (EAFOL) and to Montegrappa for making the Montegrappa Prize for First Fiction a reality. Thanks in particular to Isobel Abulhoul, Yvette Judge and the entire EAFOL team; to Charles Nahhas; and to my talented editor, Sally Williamson, and the marvellous team behind the scenes at HQ.

To the first two readers of the first draft of Coming Home, Jane Andrew and Rachel Hamilton, I’d like to say thank you for being so polite.

Heartfelt thanks to the many friends who supported me along the journey, in particular to those who believed in me long before I truly believed in myself: Sarah Baerschmidt, Arabella Pritchett, Claire Buitendag, Vicki Page, Belinda Freeman, Rohini Gill, Julia Ward Osseiran, Sophie Welch and Sibylle Dowding. Special thanks, too, to Ghazwa Dajani and Valerie Myerscough—without your help, I may never have made my deadlines.

And, finally, thanks to my family, who have stood by me every step of the way: to my parents, David and Kay, for making me believe anything was possible; to my children, Maia and Aiman, for their patience when my study door was closed; and to my husband, Sam, for his love, pep talks and fabulous plot ideas, as well as for making me laugh when I most needed to.

Table of Contents

Cover (#u05cc7bf3-6027-5d0f-a167-48c0daecfd15)

About the Author (#u1391834b-2ab8-5de3-b180-6e13ebad511a)

Title Page (#u0778f360-3383-53f2-88ac-b488c908004e)

Dedication (#uc94d383b-e720-5de6-a740-0360e8e7e6ae)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

CHAPTER 18

CHAPTER 19

CHAPTER 20

CHAPTER 21

CHAPTER 22

CHAPTER 23

CHAPTER 24

CHAPTER 25

CHAPTER 26

CHAPTER 27

CHAPTER 28

CHAPTER 29

CHAPTER 30

CHAPTER 31

CHAPTER 32

CHAPTER 33

CHAPTER 34

CHAPTER 35

CHAPTER 36

CHAPTER 37

CHAPTER 38

CHAPTER 39

CHAPTER 40

CHAPTER 41

CHAPTER 42

CHAPTER 43

CHAPTER 44

CHAPTER 45

CHAPTER 46

CHAPTER 47

CHAPTER 48

CHAPTER 49

CHAPTER 50

CHAPTER 51

CHAPTER 52

CHAPTER 53

CHAPTER 54

CHAPTER 55

CHAPTER 56

CHAPTER 57

CHAPTER 58

CHAPTER 59

CHAPTER 60

CHAPTER 61

CHAPTER 62

CHAPTER 63

CHAPTER 64

CHAPTER 65

CHAPTER 66

CHAPTER 67

CHAPTER 68

CHAPTER 69

CHAPTER 70

CHAPTER 71

CHAPTER 72

CHAPTER 73

CHAPTER 74

CHAPTER 75

Extract (#u37b4969a-a679-58ab-871c-4fa76f01bf35)

Endpages (#u19fc8561-fd7e-5dd4-9903-d55ab9677200)

Copyright (#u97ddaa58-d83b-57d1-a36f-2684f64eb4d2)

CHAPTER 1 (#u8c3d63fe-b438-5f9f-8b08-3bf9eb9fcbb8)

I hated seeing the grief counsellor, but I couldn’t get out of it. My teachers, unsure of how to handle me, had contacted social services and I’d been assigned weekly meetings with Miss Dawson, a sensible-looking lady to whom I was reluctant to speak. I blamed her for that: she should have known better than to tell me to think of her as my favourite auntie; everyone knew I didn’t have any aunties.

Every week, Miss Dawson arranged a couple of chairs to one side, near a window that looked out over the playing field. I could see my classmates kicking about in the drizzle. As far as I was concerned, the best bit about the counselling was that I was allowed access to the staff biscuit tin.

I didn’t have much to say to Miss Dawson, though. We’d spent the first two sessions locked in silence as I’d eyed the biscuits. Sometimes under the digestives I could see the edge of a custard cream—once, even a Jammie Dodger. But Miss Dawson didn’t like me rummaging in the tin, so I had to be sure I picked right the first time. A biscuit lucky dip.

Miss Dawson doodled flowers on the clipboard she kept on her knee.

‘Why won’t you talk to me?’ she sighed after we passedthe first twenty minutes of our third session together marked only by my munching. I looked at her. How stupid was she?

‘You can’t change what happened, can you?’ I hadn’t realised I was going to shout, and biscuit crumbs sprayed from my lips. ‘You can’t stop it from happening! So what’s the point of all this?’ I jumped up and hurled my biscuit at the wall. The sudden violence, the release, felt good. ‘It’s just to make the adults feel like they’re doing something! But don’t you get it? You can’t do anything! It’s too late!’

I threw myself back into the chair and glowered at her, breathing hard. What was the point? Miss Dawson’s hand had stopped mid-doodle. She locked eyes with me but she didn’t say anything. As we glared at each other, her eyes narrowed, she chewed on the end of her biro and then she nodded to herself, her lips spreading in a little smile as if she’d had some sort of epiphany.

‘OK, Evie,’ she said slowly. Her voice had changed. It wasn’t all sympathetic now. It was brisk, businesslike. I liked that more. She rummaged in her bag and pulled out a tangle of blue wool stabbed through with two knitting needles. ‘I know what we’re going to do, Evie. We’re not going to talk: we’re going to knit.’

‘I don’t know how to knit.’

‘I’m going to teach you.’

She pulled her chair over to mine, arranged the needles in my hand and showed me the repetitive movements I needed to make to produce a line of stitches. It was fiddly and unnatural, and it took all my concentration. For the first timesince June, there was no space in my head for Graham. By the end of the session, I’d knitted five rows; by the following week, a whole strip.

I was eight when I learned to knit. I haven’t stopped since.

CHAPTER 2 (#u8c3d63fe-b438-5f9f-8b08-3bf9eb9fcbb8)

I was making béchamel sauce for a lasagne when I found out that my father had died. It was late morning and the kitchen was filled with sunshine. Birdsong and the scent of acacia wafted through the open door; the flowers of the bougainvillea were so bright they looked unreal.

These are the details that stuck in my head as I struggled, in my peaceful surroundings, to take in what my mum was telling me on the phone. England seemed too far away; the news too unbelievable. The béchamel sauce, unfortunately, was at a critical stage.

‘He died in his sleep,’ Mum was saying. ‘Heart failure.’ She misread my silence as I continued to stir the sauce, my hand moving automatically as my brain fought to understand. ‘Darling,’ she said softly, ‘he probably didn’t even know.’

There was an echo on the long-distance line and I strained to hear her. I flicked off the burner and pulled the pan off the hob, knowing as I did it that the sauce would ruin; knowing also that what I was being told was bigger than that. I sat down at the kitchen table, the phone clamped to my ear, a heaviness in the pit of my stomach. I’d seen Dad in the summer—he’d been fine then. How could he be dead? So suddenly? Was this some sort of joke?

‘When I realised that he was, you know … dead,’ Mum was saying, cautiously trying out the new word, ‘I called the doctor. I could see there was nothing that could be done; no need to get the paramedics out. The doctor said he’d been dead for several hours. He called an ambulance to take him to the hospital. I followed in the car.’

‘There was no need to rush, really,’ she added, ‘because, well, you know …’ Her words tailed off.

Suddenly I found my voice. ‘I don’t believe you! Are you sure? Did they try to resuscitate him? Is there nothing they can do … no chance …?’

‘Evie. Darling. He’s gone.’

I’d dreaded a call like this ever since I’d moved to Dubai six years ago. There was much I enjoyed about living abroad, but the fear that something might happen to my parents lurked permanently at the back of my mind, waking me in a sweat in the early hours: freak accidents, strokes, cancer, heart attacks. And now that that ‘something’ had happened, I just couldn’t take it in.

On the phone, Mum sounded calm, but it was hard to tell how she was really coping.

‘How are you? Are you OK? Where are you?’ Now words poured out of me. My eyes were flicking around the kitchen and I was thinking ahead, my spare hand raking through my hair. I needed to know Mum would be all right until I could get there.

‘I’m back home now. They sent me home with a plastic bag of belongings. Glasses, keys, clothes, wedding ring …’ she said. There was a pause. I could imagine her giving herself a hug in her bobbly cardigan, her spare arm squeezing around her waist; the silent pep talk she was giving herself. She rallied. ‘I’m fine. Really. But there’s a lot to do. The funeral; the drinks and nibbles? All that stuff. I’m not sure where his Will is. And I don’t even have any sherry.’

‘Don’t worry,’ I said. ‘I’m coming. I’ll get a flight as soon as I can. I’ll be there tomorrow.’

Lasagne forgotten, I went to my bedroom, intending to get my passport out of the small safe I kept in my wardrobe but, instead, from my bottom drawer, I pulled out a faded blue manila folder. Tucked inside it was a pile of tourist leaflets I’d gathered over the past few months: seaplane rides, retro desert safaris; deep-sea fishing cruises, amphibious tours of old Dubai, camel polo lessons; menus from a clutch of top restaurants.

It was my ‘Dad’ folder; my plan of things to do when my father finally made it to Dubai. A year ago it would have been inconceivable to think that my father would fly to Dubai to see me: he’d always been ‘too busy’ when Mum came to visit. Six years, and not one visit from him—it was something I tried not to think about. If I did, it made me angry: father by name, but not by nature. Since I was eight, he’d not only been physically absent most of the time, but emotionally unavailable too. But then, last summer, for the first time in twenty years, he’d started to show an interest in my life.

‘So what’s it like over there?’ he’d asked. He’d brought us each a cup of tea and sat down with me in the garden. ‘How hot does it get? What do you do at the weekends?’ Then, tellingly, ‘What’s the museum like?’ Dad was an historian. If he was asking about museums, it meant he was thinking about visiting. And, after so many years of feeling like a spare—and not particularly wanted—part in my father’s life, the idea had come as a surprise to me—a welcome one at that: I’d lain in bed that night smiling in the dark. With Dad’s attention on me for the first time since I was little, I’d felt myself unfurling like a snowdrop in the first rays of spring sunshine. It had been a time of promise, of new beginnings. It had been a chance for us to put things right. Looking at the folder now, I raked my hands through my hair. I should have seized that chance then; insisted that Dad come to Dubai; told him straight out that I’d like him to come.

And now it would never happen.

I picked up one of the leaflets and traced the outline of a camel with my finger. Dad would have enjoyed riding across the sand dunes like Lawrence of Arabia, especially if there was a sundowner at the end of it. He’d have looked great in a kandora and ghutra, a falcon perched on his arm. Abruptly, I hurled the folder across the room, leaflets spinning from it as it frisbeed over my bed. Jumping up, I kicked out at the leaflets on the floor, sending them skidding across the laminate and under the bed.

‘Why?’ I shouted at the room. ‘Why now?’

Getting everything done in time to catch the 8 a.m. flight was a struggle. Booking a last-minute flight with the airline’s remote call centre had taken more energy than I’d felt I had to expend; a never-ending round of ‘can I put you on hold?’ while a sympathetic agent had tried to magic up a seat on the fully booked flight. Tracking down my boss on the golf course was even more difficult.

‘How long will you be away?’ he barked when his caddy finally handed him his phone at the eleventh hole. ‘Will you be back to close the issue?’

‘I don’t know,’ I said. I had no idea how long it took to organise a funeral. ‘Emily’ll cope perfectly well. I’ll leave notes; she knows what to do.’

‘Well … she’s perfectly capable, I’m sure,’ my boss said. ‘Make sure you show her what to do.’ But then he surprised me. ‘Take as long as you need … and, um … all the best.’ It didn’t come naturally to him to be nice and I could practically hear his toenails curling with the effort, but I didn’t care—with my leave approved, I sat down to write my handover notes for Emily.

My phone lay silent on the table next to me. It’d been six weeks but I still hadn’t got used to it not buzzing with constant messages from James. I’d been the one to cut him out of my life but I would have given anything to be able to hear his voice again—the voice of the old James, at least. Our lives had been spliced together for so long that my heart hadn’t yet caught up with my head. I felt like he should know about Dad, but would he even care? I rubbed my temples, then picked up the phone and dialled. He picked up on the fourth ring. One more and I’d have hung up.

‘Hello James? It’s Evie.’

I heard the sounds of a bar in the background: music, laughter.

‘Evie.’ He was surprised, confused to hear from me. ‘What’s up?’

‘Um. I just wanted to let you know that, um, my dad died last night. I’m flying to England tomorrow. For the funeral.’

James’s voice, off the phone, ‘Ssh! I’m on the phone, keep it down. Wow, sorry to hear that, Evie.’

‘Well, I just thought you might like to know. Y’know.’

‘Yes, well, thanks for telling me …’ A shout went up in the background. He was in a sports bar; a team had scored.

‘OK then, bye.’

‘Cheers.’

I shouldn’t have called. The ‘cheers’ grated more than anything. That was what James said to people he didn’t care about. I’d always felt a little sorry for them and now I was one of them. I sighed. The truth was that James really didn’t care about me; he probably never had. The only person James cared about was himself. I poured myself a large glass of wine and turned my attention to packing.

CHAPTER 3 (#u8c3d63fe-b438-5f9f-8b08-3bf9eb9fcbb8)

‘Tell me about Graham,’ Miss Dawson said. ‘Were you very close? Did you see much of him at school?’

Rain slid down the windowpanes; the playing field outside looked sodden. I took a biscuit and thought about Miss Dawson’s question. Did I see much of Graham at school? Not really. He was two years above me and our social circles didn’t overlap much. Sometimes he liked to pretend he didn’t even know me. But I remembered one day when I’d been practising handstands up against the wall. The tarmac of the school playground had been gritty with tiny stones—it was the type of grit that, when you fell, dug holes in your knees, making the blood ooze out in mini fountains. After half an hour of non-stop handstands, I’d been looking at the speckles on my palms wondering if I could do any more when I realised the bullies had surrounded me, a circle of hard seven-year-olds.

‘Do a cartwheel!’ they’d shouted, their arms linked, their faces twisted. They knew I couldn’t; they knew I was still trying.

I’d looked at the floor, willing them to find someone elseto pick on. My hands stung but, if I did a perfect handstand, would they go away?

The ringleader had started up the chant, the sing-song tone of her voice not quite hiding the menace that oozed like oil from her pores: ‘Evie can’t do a cartwheel!’ The others took up the refrain as they edged towards me, the circle closing in on its prey. ‘Evie can’t do a cartwheel!’

The lead bully had stepped forward. ‘Watch this,’ she’d said, turning her body over foot to hand to hand to foot, so slowly it looked effortless. ‘Let me help you.’ She came closer and I knew, I could tell by the way she approached, that, far from helping me, she was going to shove me onto my knees in the grit, kicking me and rubbing me in it until my socks stained red with blood. It wouldn’t have been the first time.

But then a miracle.

‘Leave her alone!’ a boy had screamed, leaping into the circle and breaking it up. ‘Get away from her now or I’ll kill you all!’ Graham had stood in a karate stance. ‘I’m a black belt! Now shove off!’

The girls had scattered, and he’d taken me by both arms. ‘Are you all right, Evie?’

I put down my knitting and looked at Miss Dawson. ‘I suppose we were close,’ I said. ‘We didn’t see much of each other at school. But, when I needed him, he was always there.’

CHAPTER 4 (#ulink_378ba407-450a-50fa-9331-c6a3a1a040f0)

I laid my lightest clothes—a couple of cotton shirts—across the top of my suitcase, then sat on the bed, pushing myself back against the pillows. My wine glass was almost empty and I upended it now, making a full mouthful of the final dregs. It was late and my body ached for bed, but my mind was buzzing. The phone call with Mum replayed in my head. My dad was dead! Still the news, half a day on and having been repeated ad nauseam on the phone to the airline, to my boss, was too big to take in; it was like it had happened to someone else. It was the plot of a book I’d read, or a movie I’d seen. It was not my life. I knew sleep wouldn’t come.

Instead, I grabbed the house keys and stepped outside. The night-time air was fragrant with the scent of hot vegetation; of plants still cooling down from the warmth of the day. I inhaled frangipani, my favourite scent, with a top note of jasmine from the bush next door. Breathing deeply, I got a waft, too, of chlorine from the neighbours’ pool.

Slipping quietly through the gate, I waited for a gap in the beach road traffic. Cars swept past me, a blur of lights and noise after the silence of my room. Taxis carried tourists to and from their late-night dinners, bars and entertainments. Eager, sunburned faces peered out at the sights; others went past with their occupants slumped, dozing, in the back. It seemed rude, disrespectful for life to continue when my father was dead.

‘My dad’s dead,’ I said into the night air, to the road, the cars, the tourists and the taxis. ‘Have a lovely evening.’

It sounded weaker than I’d imagined. I said it again, louder, to the next car: ‘Have a great evening. My dad’s dead.’

A taxi beeped, its brakes screeching as the driver slowed, keen for another fare. I saw a gap in the traffic and ran across to the island of the central reservation and stood there, sheltered by the traffic light. Sensing I was a little unhinged, I didn’t trust myself to find another gap in the traffic and waited, instead, for the green man.

On the other side, I ducked down a side street between a beauty salon and a dental clinic and picked my way down through the lanes of fishermen’s houses to the beach. The sounds of the main road receded and soon all I could hear was the scrunch of my flip-flops on the dusty street, the sound of my own breathing and the thrum of my pulse in my head. ‘Dad is dead. Dad is dead. Dad is dead.’ I broke into a run to try to make it stop, and, not too soon, there was the beach opening out in front of me: an expanse of moonlit sand, bookended on the left by the Burj Al Arab and contained in front by a low wall. Tonight the hotel had its diamonds on: a twinkling display of lights that shot up and down its spine and belly. I stopped short, realising with a jolt that Dad would now never see this sight; that there were so many things he’d now never see. I watched through one full set of the light show then I climbed over the wall and walked towards the ocean, kicking off my flip-flops and seeking out the cold under-layer of sand with my toes.

The sight of the sea, as always, calmed me. Sitting on the last edge of warm, dry sand, I stared at the water and breathed in time with the hypnotic oohs and aahs of the waves swishing in and out. The tide was receding and each wave seemed to take the sea farther away from me, a fringe of seashells marking its highest point. I looked up at the sky and wondered what happens when you die. Could Dad see me? Was he up there somewhere now, looking down on me? Had he known he was dying? Did he think about me before he died? When his life flashed before his eyes—did it even really do that?—what did he see? What was his last thought about me?

Did he even have a last thought about me?

You should have come to Dubai, I said silently to the heavens. I wanted you to come so badly. My hands formed a steeple as if I was praying and my eyes searched for the constellations Dad had shown me how to find back in the summer evenings when we were still happy: the Plough, the Little Bear and Polaris, Orion. Tonight, as usual, all I could make out above the glow of Dubai’s neon skyline was the Big Dipper and the North Star. I needed Dad there to show me the more subtle connections between the other stars. Where are you? I asked the sky.

Would Mum be all right?

She’d sounded all right on the phone but … I shifted as a shiver rippled through me. I hadn’t spoken to Miss Dawson for years now but I still remembered the last conversation we’d had about Mum.

‘She’s like an iceberg,’ the counsellor had told me. ‘She lets you see only the top layers, the top ten per cent. If that. There’s an awful lot that goes on beneath and you’ll never see that.’ She’d noticed, then, the sadness I couldn’t hide. ‘It’s not just you, pet,’ Miss Dawson had added. ‘She’s like that with everyone. Since the accident, she won’t let anyone get close.’

And now what, I wondered. My mother was all I had left, and she was the mistress—the guardian—of The Gap. It was as if she held everyone at a distance; she didn’t want to let anyone get close to her again. We wrote each other a daily email but Mum’s emails were reports of golf scores, of choir practice and of what she was cooking for supper; they could have been written by anyone. They were information bulletins, memorandums that revealed nothing of the woman underneath. They weren’t designed to keep me close. My mum hid emotion. She didn’t reach out. She skated the surface of our relationship with prim and proper etiquette but no depth whatsoever. Mind The Gap.

In my replies, I echoed Mum’s style. We exchanged huge quantities of useless information in a literary ballet that meant little. I wrote about work achievements and new restaurants, trips to the beach and what my friends were up to. I’d tried in the past to talk about more real things; about how being with James made my blood fizz; how he looked at me like he wanted to devour me. Is this love? I’d asked Mum. Did you feel this way about Dad? How do I know if he’s The One? But the replies came back as dull as the church newsletter. ‘Your friend sounds nice, dear. Did I tell you that I’m playing a new course next week?’

By the time I was starting to sense trouble with James, I’d learned that, beyond platitudes, I wouldn’t be getting emotional support from my mum: I’d be getting a new lamb recipe and what her choir was singing for the forthcoming summer concert. In our warped relationship, it was I who took care of her.

Miss Dawson had said it was a defence mechanism. ‘Your mother’s “gap” has become a part of her,’ she’d said. ‘It helps her define who she is. She doesn’t know how to fill it.’ Then she’d smiled sadly at me. ‘You’ll get closeness one day, Evie,’ she’d said. ‘From a partner; a husband; children.’

I still felt protective of Mum, though. As an adult, I felt it was my job to look after her and the question that bothered me now, sitting on the beach, was of what lay below Mum’s gap. Had she really managed to freeze her emotions, or were they still bubbling beneath? I pushed my toes into the cold sand below the surface and wondered if, as far as Mum was concerned, Dad’s death would be the earthquake that triggered the tsunami.

CHAPTER 5 (#ulink_de528055-3273-5dad-9eb3-079283e3eb66)

Just over twenty-four hours after I first spoke to Mum, at what was quite likely the highest point of the bleak afternoon, my taxi pulled up outside my parents’ Victorian semi. They lived in Woodside, a functional commuter town that couldn’t decide if it was part of South London or north-west Kent. On a sunny day, there was enough beauty, enough greenery, for you to believe it was Kent; in the drizzle, pavements slick with rain, it looked more like Greater London. It was true, though, that, if you stood at a high point and looked south, all you could see was open countryside.

Wrapped in the pashmina I’d foolishly imagined would keep me warm, I helped the driver haul my bags out of the boot, paid him and crunched across the gravel driveway to the door. Summer’s roses, which framed the entrance throughout July and August, were completely gone; the house looked bare without the lushness of their petals. I realised I hadn’t been home during winter in six years.

Before I could ring the bell I heard a bolt being drawn back, then another, then, finally, a key turning in a lock: Mum must have been watching out for me. She appeared behind the outer, glass-panelled door. There was the click of another lock, and another, and then the porch door finally opened.

‘Hello, dear; that was quick!’ she said, looking me up and down and then enveloping me in a hug. Despite the thick sweater she was wearing, she looked small, fragile, and hollow around the eyes. In my arms, she felt tiny. I noticed at once that she had a new haircut, which framed her face. She was wearing a different perfume to usual. It was light, floral, upbeat.

‘I got on the first flight I could,’ I said, pulling away and blinking in the cold morning light. I felt like I’d been up for twenty-four hours. The shadow of wine drunk on the flight crouched behind my forehead, and my eyes popped with tiredness.

‘You’ve grown your hair,’ Mum said, as I lugged my suitcase over the gravel. ‘I always thought it suited you shorter.’

I tossed my hair back defensively and followed Mum through the front door and into the living room, breathing in the familiar scent of the house in which I’d grown up. Until I stepped into the living room, the reality of being at home without Dad hadn’t hit me; I hadn’t given a moment’s thought to the physical space his absence would create. But the emptiness of his armchair was tangible. In the doorway, I stopped and stared.

‘Glass of champagne?’ Mum asked. ‘Toast your safe arrival?’

My head snapped round to look at her. It was barely three o’clock.

‘Got one open in the fridge,’ she said with a shrug. ‘Oh, don’t look at me like that! It’s a good one. I don’t want to pour it down the sink.’

‘No thanks.’ I flopped down in the armchair next to the shelves, my eyes running over the cluttered surfaces, idly clocking what was new; what Mum’s latest fad had been—she was an obsessive collector. Every spare inch housed a collection of something: thimbles, decanters, mugs, jugs, stuffed toys, dolls with china faces, books, videos, glassware, figurines. The walls, too, were plastered with paintings. The visual stimulation was overwhelming.

Mum fussed around the room, blowing dust from pieces of glass, holding them up to the shred of daylight and polishing them with a huff of breath and the hem of her skirt.

‘Sit down,’ I said. ‘Talk to me. I want to know what happened. Was it his angina? Are you all right?’

Mum leaned on the back of the sofa and sighed. ‘Yes, dear, I’m fine. Fine as can be.’

‘So, what happened? With Dad?’ Mum had told me on the phone that he’d been a bit breathless lately. I’d thought he was just unfit. ‘Had his angina got worse? Or was it just, like …?’ Bang, I was going to say but it didn’t sound right.

Mum twisted her hands together. ‘Oh, you know. He’d gone to see the doctor for his angina a week or so ago because he’d had a bit more pain than usual. I told him to mention the breathless thing, too—it might be linked. I told you about that, didn’t I? Anyway, the doctor had said not to worry, but that it was worth doing some further tests. An ECG and some other things. The appointment was supposed to be this week. It was him that I called when I found Dad. He confirmed it was heart failure and issued the death certificate himself.’ Mum looked at the floor and, when she spoke, her voice was small. ‘He was pottering in the garden earlier that day. We’d had a nice dinner. The doctor said it was just “one of those things”. “It happens”.’

‘I still can’t believe it.’

‘Neither can I.’ Mum gave herself a little shake. ‘Still. Onwards and upwards. Life goes on.’

‘And I’m here to help.’ I wanted her to know she could lean on me.

‘Yes, dear.’ She turned towards the kitchen. ‘I’ve just made some bread. I’ll pop the kettle on and we can have a nice cup of tea and some toast?’

‘Sure.’

I looked back at Dad’s chair, still trying to take it in, then something caught my eye: under the coffee table lay Dad’s cold slippers. Presumably where he’d left them two days ago. Before he died.

As I looked at them, moulded to the shape of Dad’s size elevens, it hit me again that he wasn’t coming back. Why hadn’t I made more of an effort with him? Insisted he come out that autumn? I blinked hard. I’d been protecting my mother since I was eight years old. No matter what I felt inside, I would not cry in front of her.

I hadn’t known what sort of state Mum would be in. On past performance, she could have been anything from a bit teary to shopping naked in Tesco. So I was relieved to find her acting so normal. She was chomping at the bit, desperate to get things done. I hoped it wasn’t just a front; I hoped she wasn’t hurtling headlong towards another breakdown. I wanted to ask more about how Dad had died but she didn’t give me a chance.

‘Toast’s ready,’ she said, setting the plates on the dining table with two steaming mugs of tea. ‘Eat up. We’ve a lot to do.’

I sighed.

‘Apart from the funeral, what else is there?’

Mum pulled out a notebook and ran a pencil down the page as she read a list. ‘Well, we’ll have to tell people, for a start. So far only a few friends from church know.’ We had a very small family—all four of my grandparents were dead; Dad was an only child, and Mum might as well have been one, too: she had an older brother, but I’d never met him and I’d learned years ago never to ask about him—all I knew was that he hadn’t come to her wedding. I wondered if things might be different now; perhaps it was my tiredness that made me less guarded than usual.

‘Will we let Uncle David know?’

Mum didn’t even answer. An imperceptible huff and a miniscule shake of the head, and she was off again, as if I’d never asked.

‘Once we’ve got a date for the funeral, maybe you could help me go through Dad’s address book and let people know? Tell them no flowers, too. I don’t want people wasting their money on flowers. If they want, they can give the money to charity.’

I nodded, already dreading it.

‘And then we have to arrange the funeral. We have an appointment at the funeral place up the road at eleven tomorrow—you don’t have to come, but it’d be nice if you did. Then, obviously, the catering for the party. I’ve no idea how many people will come, but I was thinking at least three hundred for the funeral, maybe a hundred will come back, so we need to think about that. And we need to speak to the crematorium—Dad wanted to be cremated, by the way—and arrange the service there and the committal.’

She looked up to see if I was still listening. I was. But I was also stunned. Dad had only died yesterday morning and already she’d gone through all of this. It was like she was competing to be PA of the year. Either that, or she was clinging onto her list like it was a piece of flotsam in a tsunami.

‘I’ve taken a couple of weeks off from work but, well, if you could help me sort out Dad’s papers and make sure that everything’s in order in terms of bank accounts, the house, insurance policies, the mortgage, bills etcetera, that’d be very helpful? Dad took care of all of those things and I don’t know where to start.’

‘Are you still enjoying work? Do you think you’ll carry on?’ Mum was a part-time administrator at the local hospital.

‘Yes. Why wouldn’t I? Dr Goodman would be lost without me. You know how he depends on me. I might even go full-time!’

‘Really?’

‘Yes! Why not?’

I shook my head, lost for words, changed the subject back. ‘What about Dad’s computer? Do you want me to close down his email account and stuff?’ Mum’s fantastic ability at the hospital had never translated to her home life: she was rubbish on the home computer, a fact that even the PC seemed to sense, given it always seemed to shut down on her midway through an email to me, causing her to lose everything.

‘Oh, yes please, darling. Maybe you could ping any house-related emails over to my email so I can get the details changed to mine. Good idea.’

Ping?

She looked at her list again. There was more?

‘And then, depending on how long you’re here for, there’ll be the scattering of the ashes. If the crem can get them to us quickly, we could probably fit that in before you go back?’

She looked at me, maybe misinterpreting my silence as reluctance. ‘I don’t really want to do it on my own,’ she said. ‘And I couldn’t ever be one of those people who keep him in a pot on the mantelpiece. Can you imagine? He’d be home more now than he ever was when he was alive!’ She burst out laughing, a raucous sound that jarred.

‘I can stay as long as you need me to,’ I said, trying not to sound churlish. ‘Of course I’ll help with the ashes.’

Mum’s laughter stopped as abruptly as it started. She opened her mouth to say something then stopped. I waited, but she must have thought the better of it.

‘Right,’ she said, noticing I’d finished my toast. ‘Why don’t you unpack and freshen up? We could look at the paperwork later?’

I stared into the middle distance, slightly dazed. Despite, or perhaps because of, the conversation we’d just had, I still had no idea what was going on in Mum’s head, and that worried me. Over the years I’d learned how to read her moods; how to avoid her flashpoints; handle her unpredictability; but now I felt I’d lost that skill. I was back to square one, almost as nervous of Mum as I’d been when I was growing up.

Perhaps it was just the lack of sleep, or maybe it was just that peculiar feeling of arriving in a different country without having psychologically left the last one, but suddenly I felt drained. I stood up and turned for the stairs, hauling my suitcase with me.

CHAPTER 6 (#ulink_67adfd31-20df-5b1f-82a9-69636d5d0b1d)

They say every expat is running away from something. I don’t want to believe it about myself but somewhere, in a dark place where I try never to look, I know it’s probably true. I was never running away from Graham; I was running away from what had happened after Graham. I heaved my suitcase onto my bed with a grunt worthy of a championship tennis player then went to have a look at Graham’s old room. It was now a little-used guest room but, despite the fact that barely anything of his remained in there, I could still feel his essence as if it were ingrained in the walls.

Graham was a typical older brother. I’m not going to lie and say we got on like two members of the Brady Bunch when we were young. There was squabbling, of course there was, and there was hitting, pinching and hair-pulling. Once Graham drove me so mad I pushed him down the stairs and then watched, aghast, as he tumbled down. I thought he’d be dead at the bottom. He cried a lot, but he was fine—still alive, nothing broken—and, boy, was I in trouble.

No one could make me as angry as Graham could—but he was my brother and, when we got on well, he was my best friend. We’d spend hours inventing games in the garden; climbing trees, making ‘tree houses’ and cutting muddy tracks in the lawn as we raced our bikes up and down, skidding around the vegetable patch, dodging under the washing line and trying not to smash into the apple tree.

As was my ritual whenever I came home, I crouched down and peered under the bed. The box was still there. Lying flat on my tummy, I stretched my arm out as far under the bed as I could, trying not to breathe in the dust, and pedalled my fingers to get a hold on it: our old Mastermind set. Sliding it out along the carpet, I opened the box and touched my fingertips to the coloured pegs. They were still in the sequence they’d been in during the last game I’d played with Dad. Yellow, yellow, red, green.

My mind slipped back to that day. Dad and I usually played the Mastermind Challenge when Graham was out. Each time Dad won, I’d be torn between pride and disappointment: disappointed that I’d lost, but proud that Dad wasn’t humouring me—proud as punch that he hadn’t ‘allowed’ me to win simply because I was eight and his daughter.

On this particular day, Graham had been neither at band practice nor football training; he’d been outside, playing Red Arrows on his bike. He’d begged me to join in—Red Arrows weren’t as much fun without a fellow plane to swoop against in death-defying near-misses—but I’d lost the last four games to Dad and was desperate to win back at least one point before the weekend was over.

Yellow, yellow, red, green. I’d chosen carefully, trying to double bluff, to avoid any obvious patterns. Dad’s opening bet had been blue, yellow, green, red—he’d known I’d think ‘blue plus yellow equals green’ and then I’d have given it a red teacher’s tick. Not this time. I’d given him the white peg for the second yellow, and he’d raised his eyebrows and rubbed his chin before slowly placing red, yellow, green, blue.

I’d known what he was thinking there, too: colours of the rainbow. I’d sighed, acting as if he was right, then given him still only the one white peg for the yellow. There was nothing predictable about my colours this time. I’d spent the previous evening in my room, going through all my predictable patterns to come up with something that didn’t fit any of them. Who knew how difficult it was to be random?

‘Evie! C’mon! I need you!’ Graham had shouted through the open patio doors to the dining room where Dad and I were playing. ‘Stop being such a boring old fart!’

‘Just one more game and I’ll come!’ I’d shouted back. ‘Just let me beat Dad!’ I loved playing Red Arrows, too, but it wasn’t the same as winning at Mastermind.

‘It’ll never happen!’ Graham had shouted, zooming back down the garden on his bike. ‘I’ll be playing on my own forever!’

Nine guesses in and Dad had had three white pegs to mark the three colours he’d guessed correctly. But he was having trouble with the fourth—I never put doubles and he knew that. The whole game had hinged on his last guess. Blue, yellow, red, green, he guessed. I’d won!

‘Well done, sweetheart!’ Dad had said as I’d jumped onto his lap for a hug. He’d ruffled my hair. ‘I’m so proud of you! What a great combination, you completely out-guessed me by choosing that double yellow.’ He’d given me a big kiss. ‘You know? I think you could be Prime Minister one day with smarts like that. Now, are you going to let me get my own back, or go and play with your brother?’

‘I’m going to play with Graham and think about my next combination!’ I’d said, putting the set into its box. ‘Is it OK if I don’t clear this game? I want to remember it forever.’

I remembered the day clearly. About a month later, Graham was dead. There was no more Mastermind with Dad after that.

I put the set carefully back into its box and, lying flat on my tummy, pushed it back into its hiding place. Standing up, I brushed the dust off my sleeve and took a deep breath.

‘Hello,’ I said softly. ‘You all right?’

There was no reply, of course.

‘Don’t worry, I’ll look after Mum,’ I said. I closed my eyes for a second, then backed quietly out of the room, pulling the door gently to behind me.

The only things left in my room from when I’d lived there were the scant clothes I’d left when I moved to Dubai, a couple of old perfumes and some of my childhood books and toys. With my blessing, Mum had redecorated after I’d left, choking the room with flowery wallpaper, adding bright curtains and changing my creaky old single bed for a double with an antique brass frame. If I half shut my eyes, I could still see past the flowers; I could see the contours and colours of the room in which I’d grown up.

Now, I lay on the bed next to my suitcase and tapped a WhatsApp message to Emily to check everything was OK at the office.

Dubai felt dreamlike, a galaxy away. My pillows were comfortable … they smelled like home.

Two hours later, as the afternoon started to turn its attention to dying, I went back downstairs, my knitting bag under my arm. I felt much better. I’d had a sleep, unpacked, had a shower and changed into something warm.

I found Mum in the living room having a cup of tea with Richard-from-down-the-road. Although I hadn’t seen him for years, I remembered him—he was one of those people who seemed to have been around forever, propping up the local church, leading the Cubs and organising community football matches and bonfires throughout my childhood. He’d taught Sunday school when I was five—and he’d seemed ancient even then. Twenty-three years later, it seems he’s only a couple of years older than Mum. A widower, at that.

Dressed in frumpy brown cords and a shabby-looking sweater, the threadbare collar of a beige shirt poking out from the crew neck, and wearing desperately unflattering glasses, he didn’t do himself any favours.

‘Forgive the clothes,’ he said, catching me looking at him. ‘Usually I dress like a pop star but I was trimming the hedges today.’

I laughed, caught out. I liked his humour.

‘Richard just popped round to give us his condolences,’ said Mum. ‘He was a huge support to me yesterday morning when I, um, “found” your father.’ She gave a little shudder. ‘He came with me to the hospital. It was ever so kind of him.’

I looked at them both. Mum was smiling at Richard, her teacup balanced daintily on her knee. She had a bit of blusher on and she looked pretty. On the mantelpiece, there was a vase of fresh flowers—thankfully not white lilies because Mum would have slammed those straight in the rubbish—and I guessed Richard had brought them. I wondered how much he knew; if he remembered what had happened to Graham. It had been talked about enough in Woodside, even if Richard and his wife hadn’t been that close to Mum and Dad at the time.

I poured myself a cup of tea from the pot and sat down.

‘Try the shortbread,’ said Mum. ‘It’s lovely.’

It was only then that I noticed the Petticoat Tails on the table. Heat flooded my face and I swiped my hand over my forehead, the sweat wet on my fingers. Petticoat Tails! Dad’s favourite! I blinked hard, the memory of Sunday afternoon teas before Graham had died, of ham sandwiches, buttered crumpets and shortbread, hitting me physically in the gut.

‘Have one. You’re too thin anyway!’ Mum nudged the plate towards me, and I stared at her. It was all wrong: Mum, Petticoat Tails, Richard.

‘Yesterday wasn’t the time for condolences,’ said Richard, turning his attention from Mum to me. ‘So I thought I’d pop by today to see how your mum was bearing up.’ He smiled at her and she looked away, almost embarrassed. ‘But it seems like she’s got everything marvellously under control.’

He nodded to himself. As if to reinforce that his words were definitely true.

I had to agree—on the surface, it did.

CHAPTER 7 (#ulink_63ec522c-b549-52b0-a358-00fce45d6d19)

‘What do you remember of that that day, Evie? Can you talk about it?’

I pulled my knitting out and picked up where I’d left off at home that morning. I was knitting my first scarf. There was a bit where I’d dropped a few stitches but I hoped it would be good enough to wear. On the playing fields outside, half of my class was playing football. I could see them through the staffroom window.

‘We were in the garden,’ I said. ‘Mum and me.’

Miss Dawson nodded.

‘I remember the sirens.’ I concentrated on the stitches falling away from my fingers; I tried not to think about the words tumbling out of my mouth. Somehow the ‘doing’ made the ‘saying’ easier.

It had been a beautiful day. The sky had been so blue I’d imagined it reaching all the way up into outer space. We’d heard the sirens while we’d been pulling weeds. I was wearing shorts and a vest and I’d been hot; sweat had been running into my eyes and I was wishing I’d worn a headband. Mum was throwing big clumps of weeds into a trug; I was copying her, pulling the bits that looked like grass andthrowing them into my own small trug. I hadn’t dared to do the weeds that looked like flowers in case I got it wrong.

‘A song came on the radio and we danced,’ I told Miss Dawson. ‘It was “Dancing Queen”.’ Mum had jumped up and run to the kitchen windowsill, where we’d balanced the radio. She’d turned up the volume and started dancing, calling to me to join her.

Mum had been strutting up and down the patio, her hands on her hips, pointing and turning like a pop star. I’d dropped my trug and tried to copy her moves. Mum had sung along, pointing at me. I remember thinking how I couldn’t imagine being seventeen.

‘Mum was going to make lemonade later, and we were going to take a picnic to the park—maybe even hire a rowing boat.’

It was then, when I was thinking about ham sandwiches and lemonade, that we’d heard the sirens. When you hear them in the distance, you don’t think that it’s your brother dying on the road. You just don’t think that. ‘Sounds like something’s happened on the bypass,’ Mum had said.

‘We heard the sirens,’ I told Miss Dawson. ‘We didn’t know they were for Graham.’

‘Oh, Evie. No. Of course you couldn’t have known.’

I barely heard Miss Dawson. I was back in the moment, stitches sliding off my knitting needles as I remembered. Mum had turned up the radio to drown out the noise. The song had finished and, out of breath and laughing, we’d gone back to our trugs. ‘Out of breath’. How that haunted me now.

I looked at my knitting, my eyes blurring with tears. I’d heard people say that I probably couldn’t remember the day—that the shock would have blunted my memory—but it wasn’t like that at all. I remembered it too well. It was just hard to find the words.

‘We had some biscuits when we went back in.’ I stopped. Until I said it, it might not have happened. I took a deep breath. ‘After a while, there was a knock at the door. It was the police.’

I remembered how funny I’d thought it was that policemen were calling: we hadn’t been burgled. ‘Perhaps they heard about the lemonade!’ I’d joked to Mum but she’d shoved me into the sitting room and I’d crouched with my ear to the door. I hadn’t been able to hear much. I’d heard only bits.

‘Very sorry … pedestrian crossing … didn’t stop … thrown thirty feet … nothing they could do …’

Then I’d heard Mum. She was stern. ‘No, you’re wrong! It can’t be! Not Graham! You’ve made a mistake!’

I’d heard her shoes clomp hard across the hall, like she was running, and I’d got away from the door just as she’d shoved through it. ‘Evie!’ she’d called. ‘The police are saying Graham’s been run over! Obviously they’re wrong because he was with Daddy! I’m going to the hospital to sort it out.’

‘Mum went with them,’ I said to Miss Dawson. ‘She put on her lipstick and went.’ I jabbed my needles into the wool. ‘The police were right … they were right.’ My voice cracked and I took a breath then carried on, my eyes on my knitting. ‘Graham had been hit cycling across a pedestrian crossing. Dad had seen the whole thing. They put him in hospital, too; they had to knock him out.’ I stared at the window. ‘They should have kept Mum in, too.’ I turned to look at Miss Dawson. ‘I wouldn’t have minded. But they didn’t. Mum had to come home on her own and look after me.’

CHAPTER 8 (#ulink_d3177520-5dcf-5251-9db4-deca846898be)

It turned out that Mum had a pretty good idea where Dad’s will might be, after all. As I sat downstairs the next morning, knitting my way through the East-to-West jetlag that had had me up at 4 a.m., I heard her clomping awkwardly down the stairs.

‘Uh,’ she grunted, kicking open the living room door and depositing four sturdy box files on the dining table. Despite the early hour, she was already dressed, coiffed and scented while I—having been up for half a century—was still in my dressing gown.

‘I think the Will might be in here,’ she said. ‘Your dad kept all his papers in these. It’s a blessing that he was such an organised man. Now. Have you had breakfast?’

Before I could reply, she carried on.

‘We’re due at the funeral place at eleven. We can’t sort this out too quickly as there are waiting lists. Poor Lily had to wait two weeks for her brother’s funeral.’

And so, after taking a shower, I hunched over the dining table and, feeling as if I might be about to open a Jack-in-the-box, released the catch on the first box. I didn’t share Mum’s confidence in Dad’s organisational skills, but no horrors jumped out; there was no explosion of random papers, just a series of fat folders, each containing what looked like the year’s statements from various bank accounts and a couple more folders of credit card statements.

Encouraged, I opened the second box and found another series of neatly labelled folders, these appearing to contain receipts and guarantees for everything that my parents had bought in the last few years, from clothes and electronics to work done on the house and car.

The next two boxes told a similar story. Dad had meticulously filed all of the paperwork essential to keep my parents’ lives running smoothly, from utility bills and insurance papers to the tax returns, invoices and payment slips for every little piece of work he’d done.

I smiled a thank you to the sky. It could go either way with historians, I’d found—some of Dad’s colleagues had been so disorganised I used to wonder how they managed to dress themselves in the morning, but others, like Dad, got pleasure out of documenting their lives; creating their own historical records, I suppose.

Flicking through the folders, I stuck a Post-it on each thing I thought needed attention—companies that needed to be told of Dad’s death; accounts and bills that needed to be transferred into Mum’s name; and those that could be closed down. As I put the most recent bank statement back on top of the pile, something caught my eye. A debit of £22,000 made just last week. Strange, I thought, sticking a Post-it on that too. I’d look more closely at it later.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/annabel-kantaria/coming-home-a-compelling-novel-with-a-shocking-twist/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Annabel Kantaria

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: An ordinary family. A devastating betrayal.‘An utterly compelling story of loss and betrayal – I loved it’ – Judy FinniganEvie has been away from home long enough to bury the pain that shaped her childhood.Now, with the sudden death of her father, she must return. Back to the same house. Back to the memories. Back to her mother.At first, coming home feels unexpectedly comforting. But, as she goes through her father’s files, Evie uncovers a secret that opens old wounds and changes her life forever.That’s only the beginning. As Evie’s world starts to shatter around her, she realises that those she loves most are also those capable of the deepest betrayal.A powerful, poignant novel, Coming Home is perfect for fans of Jodi Picoult and Liane Moriarty. Praise for Annabel Kantaria‘An utterly compelling story of loss and betrayal – I loved it’ – Judy Finnigan′A gripping debut. You won’t be able to turn the pages quick enough.′ – Bella magazine‘Compelling … fans of Jodi Picoult and Liane Moriarty will enjoy this powerful new book’ – Candis′[A] clever, tense thriller about a family falling apart′ – Heat