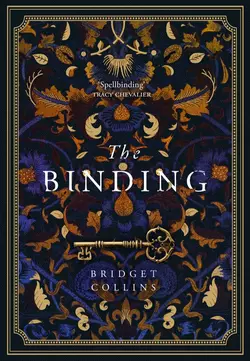

The Binding

Бриджет Коллинз

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1241.52 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: ‘I wish I had written it’ Erin KellyImagine you could erase your grief.Imagine you could forget your pain.Imagine you could hide a secret.Forever.Emmett Farmer is working in the fields when a letter arrives summoning him to begin an apprenticeship. He will work for a Bookbinder, a vocation that arouses fear, superstition and prejudice – but one neither he nor his parents can afford to refuse.He will learn to hand-craft beautiful volumes, and within each he will capture something unique and extraordinary: a memory. If there’s something you want to forget, he can help. If there’s something you need to erase, he can assist. Your past will be stored safely in a book and you will never remember your secret, however terrible.In a vault under his mentor’s workshop, row upon row of books – and memories – are meticulously stored and recorded.Then one day Emmett makes an astonishing discovery: one of them has his name on it.THE BINDING is an unforgettable, magical novel: a boundary-defying love story and a unique literary event.