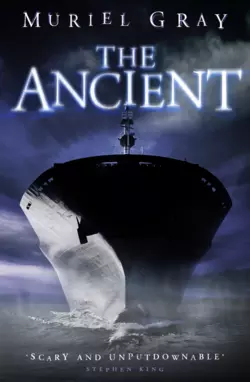

The Ancient

The Ancient

Muriel Gray

Alien, on a container ship.

‘Scary and unputdownable’, Stephen King

Amongst towering mountains of trash in the backstreets of Lima, three young boys are trying to raise an ancient demon. They don't think their incantation has worked; but that night a teenage drugrunner is gunned down across their makeshift altar. As his killers walk away, his body stirs. Not because it still contains a spark of life. But because something is stirring beneath it…

Port Callao. The MV Lysicrates, a three-quarter-mile long supertanker, is being loaded with hundreds of tonnes of trash. Watching from the bridge, in a bleary state of hungover gloom, is second-in-command Matthew Cotton; more interesting is the arrival of a young American student who has missed the boat she should have been on.

They should have paid more attention to the trash.

MURIEL GRAY

The Ancient

HarperVoyager an imprint of

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk (http://www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2015

Copyright © Muriel Gray 2002, 2015

Cover photograph © Stewart Sutton/Getty Images; Shutterstock.com (sky, sea, mist)

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Muriel Gray asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008158262

Ebook Edition © December 2015 ISBN: 9780007404438

Version: 2015-10-29

For

Hamish, Hector, Rowan and

Angus James Barbour, with love

Contents

Cover (#u22c7ece8-8a04-58d5-b758-1faf363b05b2)

Title Page (#udf0ad4fd-199f-56b6-9f0f-10bf9131309f)

Copyright (#u050d2480-04fe-5f20-b56e-df92e843e86c)

Dedication (#u051123df-8061-5b4d-8544-cd597f128b0c)

Chapter 1 (#u5af73880-1284-5490-8960-b80337763538)

Chapter 2 (#u80b76ef9-d266-5437-a349-f9e3719fc660)

Chapter 3 (#u97322576-0625-5ca4-b5a0-8b938181a73c)

Chapter 4 (#u1a355049-dbca-51b0-8177-bb588c23e061)

Chapter 5 (#ufc379e36-ba0f-5f10-afc3-ab0b9bd0c3f0)

Chapter 6 (#u02cbd88d-ec88-5bb7-abdb-b0324714c992)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also By Muriel Gray (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1 (#u0822ac7f-3760-5911-9571-db132baf9de4)

In other circumstances, Eugenio might have given the rat a name. Rats, and the bold rats of this sun-baked slum more than most, were hard to capture. He might have kept it under a crate and thrown it pieces of food, simply to be its master, to control it, to confine it, the way his own life was determined by pinched-faced adults.

But this rat was to die. It was their sacrifice, and as such, it needed no name.

The creature writhed and thrashed in the soiled canvas bag that Eugenio held out from his body. His two companions watched, eyes big in anticipation, waiting for their leader, their priest, to guide them.

As the oldest at nine years of age, Eugenio felt the weight of that responsibility: he moulded his face into an expression of suitable solemnity as he kicked at a piece of hardboard in the rubbish.

‘Here.’

The two smaller boys glanced at him, then went to work, pulling the wood from the malodorous pile, farmers lifting a diseased crop from a toxic field. This slowly-shifting glacier of garbage was their home, their playground, their store cupboard. The fetor had long since ceased to make any impact on their senses, nor did the uniformity of its colour and texture, a mosaic of greys and primary hues, fill them with despair. They were the naturalized creatures of this place and the stained Nike T-shirts they wore ticked them with approval.

The board was extricated and positioned at the mute head-nodded directions of Eugenio the priest. He squinted at the sun to check its position and was satisfied.

Both boys knew what to do. The smaller took the awful thing, the thing none of them wanted to touch, from his plastic carrier bag and laid it carefully in the centre of this makeshift altar, while the other unsheathed the salvaged hunting knife.

Eugenio glanced at the doll, if anything so repugnant could be described as a doll. Its head was formed from the skull of rat, which had been stitched onto the leather body by means of a strap through the sockets, onto which two black orbs of cloudy stone had been glued to mimic eyes. Below it, tiny irregular tin teeth had been meticulously embedded into the yellowed bone, bestowing a manic grin upon the skull that was worse than the grimace of any corpse. It topped a grotesque torso, worn shiny leather that described a bulbous belly, gashed open and stitched back with the same loving craftsmanship as the head attachment. There was a cavity inside, open and ready to receive their sacrifice. It was ovoid like a recently-vacated womb, hardened and blackened from previous offerings, and the scabbed interior gave the slit womb an authenticity as though any baby’s exit had been a bloody and fatal one. But if the figure was meant to be female, then the horrifically-oversized leather penis that hung obscenely between its legs was a strange contradiction. The arms and legs were thin, reptile-like, too long for the squat body; but the worse aspect of their fragility were the long, serrated shards of metal, like broken claws, that completed each limb.

Eugenio began to feel nervous. If his aunt discovered that he had taken this figure from her few possessions she would make him suffer. Her rage was always contained and deadly, and he swallowed at the idea of what she might do. But she would not know. The ceremony would be over in minutes and if successful, would grant him the power that would make even her spite meaningless. His greatest fear was that it wouldn’t work. His knowledge was patchy, only a tiny portion of what his aunt and her clients discussed in their drugged ramblings. The rest he was going to invent. Somehow he felt sure that improvisation would suffice. The power of the ceremony after all, he had convinced himself, was in the intention, not the vocabulary.

Tiny as it was, it took all three of them to hold the rat down as Eugenio sliced through its filthy fur. It bared its teeth and piped its agony in a series of shrill screams that fascinated the boys as they worked. They heard rats fight all the time, but the piercing, high-pitched squeals that accompanied those scuffles, so high they operated on the very edge of human hearing, were quite unlike this. These protestations were guttural, having a power that defied the small lungs that expelled them, and secretly, Eugenio enjoyed the sound. He hated rats. They crawled on him at night, pissing on his blanket, boldly feeding on the scraps of food that were never cleaned from the hard-packed earthen floor of his family’s shack. Now here was fitting revenge.

Delicately Eugenio sliced out the beating heart and pincered the ludicrously tiny organ between thumb and forefinger, quickly transferring it to the leather slit, poking it into place with a bloody finger and wiping his hand unconsciously on the side of his shorts.

Three pairs of eyes darted between each other’s faces then closed in reverence.

Eugenio cleared his throat and began to speak with a curious mixture of the self-consciousness of a young boy, and the gravitas of a priest.

‘Fallen One – whether male or female, at any rate commander of heat and reproduction, being one who even with his spittle can work sorcery – where art thou?’

He opened his eyes and looked at the now-still heart in its leather nest, but the figure’s empty eye-sockets stared past him into space, oblivious to the gift in its belly. Eugenio closed his eyes again, this time screwing them tightly shut as though the effort would increase his potency.

‘I shall be seen by thee, and thou wilt know me. Would that thou were not hidden from this son of thine. Eat of this sacrificed heart, and also of the one still beating in the body of thy servant.’

He stopped. This was as much as he had memorized from his aunt. From now on the quality of the prayer would plummet. He would have to make it up. His saliva dried, both from the tension of what he desired to happen, and the terror of looking a fool in front of his companions.

‘I am … no one. You … thou … are eternity. We want you to come to us … and to give us power to … do many things.’

One of the boys opened his eyes and looked across at his leader. The change in tone had not gone unnoticed. Eyes still closed tightly, Eugenio continued undaunted.

‘Come to us now, as you have come to others before us. As you have come to the older ones before the Spanish came.’

He opened his eyes and saw that his entire congregation of two were now staring at him.

He stared back defiantly, then let his eyes drop to the useless, static doll, and the flat-furred husk of the rat, mottling the already-stained hardboard altar with its thick, poisonous blood.

A terrifying and powerful bellow broke the silence, and the three boys jumped in fright.

There was a brief moment of confusion, a moment in which they believed the Fallen One had answered them with that fearsome bestial noise, and then their inbred survival instincts processed the information and made them scatter like rats themselves. There was trouble approaching. But not of the supernatural kind. In seconds they had disappeared.

Their hurried departure knocked the altar at an angle, and the figure flopped over, slowly letting its tiny prize slither onto the wood and down into the trash.

The shout was repeated, but this time it was followed by a sharp laugh from another source. Scrabbling in the rubbish like a runner in sand dunes, a youth burst over the short horizon of plastic bottles, car tyres and old mattresses.

His face was contorted with fear, his mouth a black downward crescent of horror, as he stumbled across the unforgiving terrain like a drunk. Close behind came two men, running, but with less urgency, the broader of the two allowing a gun to dangle casually from his hand.

Anything could have tripped the runner; a piece of metal lying beneath the cartons and rotting vegetable matter; a rope tangled in the mesh of discarded chicken wire; a broken drawer from a chest protruding from the sea of trash like a dorsal fin. But it was actually the hardboard altar that snagged the pursued man’s foot, and sent him slapping into the undulating mush with a soft, revolting thud.

His assailants slowed then approached him with party smiles, while the fallen youth stayed face-down in the trash, shoulders heaving, hands closing on discarded newspapers and coffee grounds.

There was no dialogue, no conferring or taunting. The man with the gun in his hand swivelled his limp wrist and shot the youth through the back of the head.

It was a gun without the benefit of a silencer. The sharp crack reverberated shamelessly through the still afternoon. Both men looked around like lions after a kill. Not afraid, nor guilty, but bored, indifferent, blank.

No resident of this filthy colony would come to investigate. No policemen would gallop to a chase. In this landscape they were the law. They had the gun. The smaller of the two men bent down and fumbled in the dead youth’s jacket until he had retrieved the tightly-packed plastic envelope of white powder that had sentenced him to death.

Even then, there was no conversation, their companionship being the company of animals, dumb and cunning at the same time.

They turned to go, and as though some primitive electrical connection had been made in his brain to remind him of his last deed, the executioner turned back and spent one more bullet on the corpse.

This time the trajectory took it through the very top of the skull. He watched for a beat with satisfaction as the back of the head burst off and a dark black and grey mess oozed from the splintered head. Then he turned and followed his companion.

The leather doll lay on its side mere inches from the dead youth’s head, its impassive features regarding the remains of the human like a satisfied lover. Eugenio’s aunt would take her time in punishing the nephew who stole from her when she discovered that the doll had gone. It was old. Very old. She treasured it as nothing else, harbouring sick and atavistic fantasies about what it might do for her tragic life if she could unleash its rumoured power.

For Eugenio would not retrieve it.

Because as only the confused flies that had settled to sup on the viscous meal before them, and the blazing indifferent sun above witnessed, the impassive handstitched abomination began to shift slightly. Slowly and almost imperceptibly at first, its limbs began to be drawn down into the garbage. Not naturally, the way an object may shift and settle with gravity, but like prey caught by something unseen. In a matter of seconds the doll had drowned and was gone down into the trash – along with its still companion.

As the two figures, man and leather, sank beneath the fetid surface, it was only a matter of minutes before the burst video tapes and toilet paper, the mashed cloth and food remains, had joined once again to make a new skin over their secret and buried possession.

2 (#u0822ac7f-3760-5911-9571-db132baf9de4)

Just one short glimpse was all the dusty window afforded, but it was enough to confirm she was too late. Esther Mulholland wiped the glass with the flat of her hand, as if smearing more grime across the bus window would somehow make it not true. But it was true. The dock had revealed itself briefly between a low warehouse and some shanty huts and there, silhouetted against a glittering late-afternoon sea were four ships, none of them the one she had the ticket for.

She leant her head against the window and quickly removed it again as the bus dived into a pothole, shaking her bones and battering her forehead against the glass. The woman beside her, who had been nursing a fat, scabbed chicken on her lap for the entire journey, cackled and nodded a toothless grin at the bus in general as though it were somehow obeying her command. Esther had been watching her with fascination for the last five hours, amused as the wizened, squat old woman somehow anticipated the chicken before it shit, opening her legs at just the right time to let the startled beast squirt onto the floor beneath her.

The chicken, Esther reasoned in her most bored moments, must tense its muscles before taking a dump, allowing the woman who cupped it in her callused hands to feel its contortions and take action. But whereas this had been a charming diversion a hundred miles back in the stony monotony of the Peruvian countryside, now it was irritating her. The smell of the baking chicken shit on the floor and the musky reek of unwashed human flesh, which very much included her own, was making her stomach contents shift.

Unless that container ship was hiding, and it was unlikely that 150,000 tonnes of metal could achieve such a trick, then she was well and truly stranded.

It had sailed, and with it had gone her only means of getting home. It wasn’t like Esther to be irresponsible. The diversion to the temple in Lacouz had cost her only five days, and she had calculated she would make it up on the journey back from Cuzco. And she would have done, had it not been for the curious, infuriating thing that had happened in the shanty town where she’d camped overnight to wait for the bus.

Esther had become aware, quite gradually, that a small Peruvian man, a peasant from the plateau, judging by his dress, had been following her all day, staring. He was there outside the tiny store where she bought mineral water and biscuits for the bus journey. He was there when she packed up her tent, standing a short distance away, his gaze unflinching. And he was there, gazing from the other side of the dirt road, when she sat in the shade at the side of the road, her back against a cool stone wall, waiting for the one and only weekly bus to Callao. She was used to being stared at by people the further she had strayed from the cities, but this was different. He was not looking at her with that naked and childlike curiosity natives have for foreigners. His was the stare of someone who was waiting for something. She’d tried waving, acknowledging his presence, but he’d merely continued to look. Esther had been getting freaked by it, and was glad to be leaving the town. But as she sat against that wall, she’d decided to meet his eyes and stare him out. All she remembered now was that his eyes had been slits as he screwed them up against the sun, and yet as she stared at him, she still felt the intensity of their scrutiny. She had felt her own eyes growing heavy, and that was simply all she could recall. When she’d woken up, her head slumped forward on her chest, her neck agonizingly cramped, the man was gone, and more importantly, so was the bus.

Her fury at her idiocy was incandescent, but pointless. There had been nothing for it but to wait it out for another week. And so here she was, seven days late, but at least she’d got here.

The optimistic part of her had thought that maybe the ship would be late leaving, that maybe the kind of luck a girl her age took for granted would hold out. But quite clearly it hadn’t, and the truth was, she was stumped, stuck in the nightmarish industrial port of Callao with a non-refundable ticket for a ship that wouldn’t be back this way for over a month.

Her fellow passenger opened her legs to let the chicken shit again, and Esther closed her eyes. Options. As long as you were alive, breathing, talking and walking, there were always options. She held that thought, but on her own chicken-free lap her hands made fists as if they knew better.

The bar didn’t have a sign outside because it didn’t have a name. It was housed in a metal shed that had once served as the offices of a coal-shipping merchant. Then it might have had desks, angle-poise lamps, piles of documents, calendars on the walls, fax machines and wastepaper bins. Now it was simply a shed. Running parallel to one wall was a long L-shaped wooden board nailed to metal trestle legs that created a crude barrier between the clients and a poverty-stricken gantry of a few greasy bottles of spirits and crates of unrefrigerated beer. On the wall a small portable TV was attached to a metal bracket. Its flickering images fought against the broad shafts of sunlight that filtered from high slits of windows, light that was made solid by the thick fog of cigarette smoke. A coat-hanger aerial stuck on with duct tape accounted for the snowy, hissing reception of the Brazilian game-show that was being watched by the occupants of the shed. Esther had time to take in these figures before they registered her quiet entrance, and it did nothing to lift her spirits.

About a dozen men slumped forward from the hip across the wooden bar, their positions so similar they could have been members of some obscure formation team. Each held a cigarette in one hand, the other cradling a drink, and their heads were uniformly tilted up to stare at the glow of the TV. The barman’s position was in exactly the same aspect, but in mirror image. Even though his body was facing Esther, his head was twisted to watch the screen and he failed to notice her entering until the cheap double plywood door banged dramatically back on its hinges. But the pause had given her time to locate what she’d come in for, and without catching the man’s eye Esther strode as purposefully across the room as her massive back-pack would allow to the wall-mounted telephone. There was only a one-hour time difference in Texas. She pictured exactly what Mort would be doing right now as she waited for the Lily Tomlin-impersonating AT&T woman to connect her.

Of course he would let the phone ring as long he could. His chair would be on its back two legs, leant against the wall of the trailer where he could monitor the residents of Selby Rise Park from the long window above his desk, and keep a doting eye on his ugly mutt tethered to a stake by the door as it barked at friend and foe alike. He would have a cheroot between his rough lips and a bottle of beer in his fist, and there was nothing on this earth that would make him take a call collect from Peru or anywhere else.

‘No reply, caller.’

Esther scratched at the wall with a finger nail.

‘He always takes a long time to answer. Can you give it a few more rings?’

The operator made no reply and Esther was about to hang up, assuming the call was terminated, but a few seconds later she heard the connection being made. It was weird hearing Mort’s voice so far away, a voice that belonged in another world.

‘Yeah?’

‘AT&T. I have a call collect from Callao, Peru, from Esther Mulholland. Will you accept?’

‘What?’

‘I have a call collect …’

‘Yeah, yeah. I got the stingy bastard call collect bit, sweetheart. Where the fuck you say it’s from again?’

There was a pause as the operator pondered whether to hang up on the profane recipient or not, and then she said curtly, ‘Peru. South America.’

‘No shit!’

Esther heard him chuckle.

‘And it’s Benny Mulholland’s girl, you say? The one without the fuckin’ dimes?’

‘Will you accept the call?’

‘Huh? Like all of a fuckin’ sudden I’m an answerin’ service for her old man? Tell her to send a fuckin’ postcard.’

He hung up. The operator cleared her throat. ‘I’m sorry, caller. The number will not accept.’

‘I gathered. Thanks.’

Esther put the phone down gently. She had absolutely no idea why she’d made that call. Even if a miracle had happened and Mort Lenholf had taken her call, what did she expect him to do? Benny would be blind drunk by now, asleep in the green armchair in front of a blaring TV. Mort could hammer on Benny’s trailer door as long and hard as he liked but she knew it would take a sledge hammer to the kneecap even to make him stir. And the thought of her dad being able to help out in a situation like this was equally ludicrous. Benny Mulholland had probably just enough cash left from his welfare cheque to get ratted every night until the next one was due.

He wasn’t exactly in a position to call American Express and have them wire his daughter a ticket home. She decided she had simply been homesick. Only for a moment, and only in a very abstract way, since home was ten types of shit and then ten more. But it had been an emotion profound enough to want to make contact, and now it left her feeling even more bereft than before. Despite having been to the most remote and inhospitable corners of Peru on everything from foot to mule, it was the first stirring of loneliness she’d felt in the whole three months of travelling.

Esther sighed and turned back into the room. The formation team of drinkers were now all looking her way. The men, although similar in posture, were varied in nationality. A handful were obviously Peruvian, their faces from the unchanged gene pool that could be seen quite clearly on thousand-year-old Inca, Aztec and Meso-American sculpture. Stevedores by the look of their coveralls, and not friendly.

There was a smattering of Filipinos and Chinese, some with epaulettes on stained nylon shirts that at least meant they were merchant crew and not dangerous. Only one face looked western, but it was such a familiar mess of mildly intoxicated self-pity mixed with latent anger that she looked away quickly in case she somehow ignited it. The barman was staring at her with naked hostility, but it was another kind of look in the assembled male company’s eyes that was making her uncomfortable. Esther wished she wasn’t wearing shorts. One of the Peruvians taking a very long look at her tanned, muscular legs said something that made his hunched companions snigger like schoolboys, and a flicker of indignant rage began to grow in Esther’s belly. It was important to leave, so she lifted her pack and made for the door.

‘He’s pissed off on account you didn’t buy a drink.’

It was an American voice coming from the western face. Esther stopped and faced him, but he had already turned to the TV again, his back to her.

‘Who is?’ asked Esther in a voice smaller than she would have liked.

‘Prince Rameses the third. Who d’you figure?’

Esther stared at the back of his head until her silence made him turn again. He spoke without taking the cigarette from his mouth so that it swayed like a conductor’s baton with every word.

‘The barman, honey, that’s who.’

‘I guessed they don’t serve women in here.’

He took the cigarette from his mouth, blew a cloud of smoke and squinted at her. ‘They don’t. Only liquor.’

Most of the men had joined this objectionable man in turning back to the TV, maybe thinking western man to western woman was a cultural bond too strong to break or maybe because they were simply bored with the task of making her uncomfortable.

Only a very drunk Filipino and a dull-eyed stevedore continued to stare. She was grateful for the shift in attention and it emboldened her.

‘Uh-huh? Well maybe you can explain to him it’s a shade up-market for me. Guess I’m not dressed smart enough.’

The man looked at her closely and this time it was with something approaching sympathy. Maybe he heard the slight break in her voice. Maybe he’d listened to her fruitless call home. Maybe neither of these. But it softened his face and the tiny glimmer of warmth in his bleary eyes relaxed a part of Esther that was gearing up for a fight.

‘Shame. Looks like you could use a drink.’

He said it softly, almost as though he were talking to himself, and since the tone lacked any kind of lascivious or suggestive undercurrent, the words being nothing more than an acutely accurate observation, Esther inexplicably felt a lump of emotion welling at the back of her throat.

For no apparent reason, she wanted to cry, and at the same time, yes, her mouth was already moistening at the realization that a beer would be just about the most welcome thing in the world right now. She gulped back her curiously unwelcome emotion.

‘They serve anything apart from paint stripper?’

The man smiled, then turned to the sullen barman and said something quietly. Reluctantly the man bent and Esther heard the unmistakable rubber thud of a concealed ice-box door being closed. A bottle of beer was placed on the wooden board, the cold glass misting in the heat.

Esther looked from the bottle to the American and back again, wrestling with the folly of continuing this uneasy relationship.

What was she afraid of? In the last three months she had travelled and slept under the stars with a band of near-silent alpaca shepherds, walked alone for weeks in the mountains, and resisted the advances of two nightmarish Australian archaeologists.

She had stood on the edge of the world, as awed and terrified by the green desert of jungle that stretched eastwards to seeming infinity as the Incas who had halted the progress of their empire at almost the same spot had been. A dipso American merchant seaman and a few ground-down working men were not going to cause her trouble, even if they wanted to, which judging by their renewed attention to the Brazilian game-show host now hooking his arm round what looked like a Vegas showgirl, was not high in their priorities.

She walked forward, touched the bottle lightly with her fingers and gave the barman a look that enquired how much she owed him.

‘On me,’ said her self-appointed host.

Before she could protest and pretend that she would consider it improper, the man behaved outstandingly properly and offered his right hand as though she were a visiting college inspector and he the principal.

‘Matthew Cotton. Enriched to hear my native tongue.’

Esther studied him for a beat then took the hand. ‘Esther Mulholland.’ She removed her hand and touched the bottle again. ‘Thanks.’

The beer was delicious. She took two long swallows, closing her eyes as the freezing, bitter liquid fizzed at the back of her dry throat.

‘They write up Pedro’s joint in some back-packers’ guide, or did you just get lost?’

Esther wiped her mouth with the sleeve of her sweatshirt. ‘The guys at the dock gate said this was the only phone.’

Matthew Cotton nodded through another cloud of smoke. ‘Yeah. Guess it is.’

‘Nice,’ said Esther, gesturing to the room in general with her bottle.

‘It’s also the only bar.’

Esther took another swallow, watching him as he shrugged to qualify his statement. ‘You off a boat?’

Matthew nodded. ‘Lysicrates. That pile of shit they’re loading.’

‘Just a long shot, but has the Valiant Ellanda been in?’

Matthew looked up at her with mild surprise. ‘You some kind of cargo boat fanatic?’

‘Cargo boat passenger whose boat looks like having sailed.’

Matthew raised an interested eyebrow, then turned his glass round in a big hand as he thought. ‘Valiant Ellanda. Container ship. Right? Big mother.’

Esther nodded, enthusiastically.

‘Sailed last week.’

Esther nodded again weakly.

‘Then guess you got a little time to kill.’

‘I wish. Due back at college in ten days.’

‘They’ll live.’

Esther looked at the bar. ‘I’m military. Scholarship.’

‘Yeah?’

‘Yeah.’

Matthew was looking at her more closely now, continuing to study her face as he drained the last of some yellowish spirit that had filled his glass. Without even looking at the barman, he gestured with the empty vessel and it was filled nearly to the brim. Esther looked away, reminded of Benny and the tiny, unpleasant ritualistic mannerisms that all alcoholics shared.

‘What they do then, if you’re late? Shoot you?’

‘Put it this way: military students don’t get a lot of slack to dress up in tie-dye vests and wave placards. And you sure as hell don’t get to pick when you show up for semester.’

Matthew tipped the glass back and emptied half of it, baring his teeth in a snarl as the liquid drained down his throat.

‘Bummer,’ he croaked.

‘You got that right.’

Matthew turned his head back up to the TV and leaned forward on his elbows. Esther waited to see if the conversation would be continued and when it was clear that it would not, she drained the rest of her beer and made ready to go. She picked up her pack.

‘We sail for Texas. Two days’ time.’

He spoke as though talking to the game-show host.

‘Sorry?’

‘Port Arthur.’

Esther’s heart beat a little faster, then it slowed and sank.

‘My ticket’s non-refundable.’

‘Aw, bullshit. Most companies say that stuff. They’ll do a deal.’

Esther shook her head. ‘Not with this ticket. Even the cheapest cargo ship ticket is way out of my reach. I’m only here ’cause a geek I dated at college has a dad who works for the shipping company. Man, to think I put up with that guy’s bad breath and stinking taste in movies for at least two months to get that ticket.’

She paused and looked at the floor.

‘And just on account of wanting to see some shitty old temple they’ve only just half dug out the grit, I’ve blown it. Big time.’

Matthew was still looking at the screen, but he was smiling. ‘What’d he make you see?’

‘Waterworld, for one.’

‘Jesus.’

‘Yeah.’

Matthew stared at the screen a little more, then looked at his wristwatch. ‘Gimme an hour then come by the boat. Captain’s pretty easy going.’

Esther put her pack down slowly. ‘For real?’

‘No risk to me, honey. He can only say no.’

‘What rank are you?’

Matthew turned to her, a quite different look in his eye now, one that was difficult to read but undeniably harder than when he’d last looked at her. ‘First officer.’

Esther cleared her throat, embarrassed, though not quite sure why. ‘Right. Great.’

He looked back at the screen and Esther took the hint.

‘An hour then.’

He made no reply.

She hooked the pack over her shoulder and made for the door. ‘Thanks for the beer.’

‘Sure.’

The plywood door banged shut again and although there was still an inch left in his glass, Matthew Cotton gestured to the barman. It was important to think ahead. After all, he would have drained that inch before the bottle was uncorked.

3 (#u0822ac7f-3760-5911-9571-db132baf9de4)

As the giant crane swung on its arc, the sun shining between the criss-crossed metal girders strobed across the deck of the MV Lysicrates, and bugged the tits off its first officer.

Matthew Cotton blinked against it as he leant heavily on the ship’s taff rail and watched Esther’s predicament with amusement. He was leaning heavily because he was only a few drinks away from the oblivion he’d been chasing since noon, and he watched with amusement because her ire was becoming comical.

‘Give the greasy little sucker some cash,’ he mouthed at her, then took another deep swallow from a can of thin South American beer.

As if she’d heard him from the unlikely distance of fifty yards, she turned her head and squinted up at the ship, gesturing violently again at the vessel to the undernourished harbour security guard, who was no longer even looking at her. The guard flicked his hand dismissively in her direction as though warding off a fly, and shifted his weight from one bony leg to the other. She towered above this little man, and perhaps if he hadn’t sported an ancient gun in a battered leather holster by his hip, she would simply have elbowed him out of the way and walked on.

That option not open to a woman with an instinct for survival, she was vigorously pursuing the only other one, which was to shout.

In a moment Matthew would rescue her, but for now he was using the time just to look. There hadn’t been the time or space to examine her properly in the smoky little bar, but now he was in a position to study her without fear of spiky feminine reprisal.

She was too far off for him to take in close detail, but already he liked the suggestion of athleticism in her angry body, the way she was practically stamping her foot, and when she mashed an exasperated hand into her hair he imagined he could register its shine.

He smiled and wiped his mouth clean of the acrid beer foam; shifted a drinker’s phlegm from his throat.

‘Hey! Hector!’ His shout made the diminutive man look up lazily. Though he couldn’t make out her words, Matthew assumed she had been braying at the guard in English that merely increased in volume as understanding diminished. No matter what her circumstances were, and if he were honest he was so loaded now he could barely remember their conversation, she was just your average American back-packing kid. Shout down what you can’t control. He raked around for his best Spanish.

‘Let her aboard. She’s a passenger.’ He hesitated, then added for no reason other than mischief, ‘A little something for the crew.’

The guard scratched at his balls and did nothing. Matthew waited. He knew these people. To react to anything immediately was a sign of defeat. Esther waited too, her eyes narrowed to slits in Matthew’s direction.

The weary Peruvian hand motioned again, this time obliquely directing her towards the gangway, then the man squatted down and got busy picking his teeth, as though all along his objection had been that she was preventing him from performing this important task.

She took her time coming aboard, pulling on that enormous back-pack complete with tent, hanging tin mugs and water bottles, then walked slowly forward with the gait of someone used to carrying a large burden.

As she came closer Matthew noted the deep tan on the thighs that protruded from her patterned shorts, and the incongruously masculine muscles that made them move with grace under such weight.

He stayed where he was, but lifted his head to greet her as she negotiated the skinny drawbridge of wood that was suspended over the moat of Pacific Ocean below. ‘They don’t speak English too good, those guys,’ he said with what he imagined was a boyish grin.

She stopped and rubbed at her scalp again. ‘You cleared it then?’

Matthew squinted, uncomprehending.

‘With the captain?’

He grinned, swaying slightly. ‘Aw, yeah. Sure. Sure I did.’

She looked doubtful, and the sudden childlike anxiety that crossed her face, the expression of a disappointed kid, touched a nerve in the deep drunken miasma that was enveloping Matthew Cotton. He breathed quickly and sharply through his nose and tried to focus, tried harder to clear his brain.

‘Straight up. He’s cool. You get the owner’s cabin. It’s cunningly marked “owner’s cabin” on D-deck. Through there, two floors up. Third on the right. Not locked.’

Her face lit with relief, then a more unpleasant emotion betrayed itself as her eyes strayed to the beer can in Matthew’s fist. Pity.

‘Listen. Thanks. I owe you.’

Matthew nodded, looking away to avoid her pitying eyes, and she walked towards the passenger block, the cups and pan clanking on her pack.

‘By the way.’

He didn’t look round. He didn’t want to hear any addendum right now. Nor look back into the eyes of an attractive young girl who was finding a drunken older man sad.

‘Matthew?’

She spoke his name so gently it broke his resolve and he turned.

‘Huh?’

‘I think you’ll find that grammatically, “little something” in Spanish, when you refer to an object with contempt, uses the diminutive to emphasize the colloquialism.’

The Lysicrates’ only passenger scanned the accommodation block and disappeared through the door from the poop deck.

Matthew watched the heavy metal lozenge long after it swung shut, then drained his beer, crushed the can and threw it into the water below.

Esther Mulholland liked to pee in the shower. When the water was perfect, the hot stream of urine that spiralled from leg to leg was without temperature. Visible, but not tangible, it joined her with the needles of water in a way that made her sigh with satisfaction. It had been so long since she had revelled in this ritual that the developed world thought so important, this rinsing of the body that separated them from the savages.

It felt like a return. She let the hot water batter her for at least ten minutes, opening her mouth to let it run in and out, then stepped from the tiny plastic tray into the hot cabin.

Esther put her hands on either side of the porthole and leant her forehead against the glass. The circular window looked out onto a serpentine collection of pipes, their paint peeling like a disease, and beyond them the port of Callao clanked and whined with industry.

So what if the ship was shitty, this was luck beyond her dreams. She knew it was irregular, probably illegal. Bulk carriers didn’t usually take paying passengers, only the bigger ships, the ones full of officers’ bored wives slowly drinking themselves to death on bleak industrial decks, armed with the civilized pretence that somehow every hour was cocktail hour. But if the drunken first officer and his malleable captain were happy to take her, she was ecstatic to accept. If it was against the law then, hell, it would be their heads on the block not hers.

And look what she got for free. The owner’s cabin, with shower. A seventies homage to Formica, flowered curtains and hairy carpet tiles, a cell of privacy that gave her a whole four days before they docked in Texas to make sense of the hundreds of pages of scribbles she’d made in her tattered red notebook, and more importantly, translate the pile of Dictaphone tapes. She grabbed a thin towel stamped with some other ship’s name, rubbed at her hair and sat down heavily on the foam sofa. This was going to get her a first. A big fat, fuck-off-I-told-you-I-could-do-it degree, the kind that only the lucky rich kids walked away with, regardless of what was between their ears. Right now she felt luckier than hell. She laid the excuse for a towel over her face and lay back with a smile.

Hold number three was still dripping from the high-pressure hoses that had bombarded its sides. Now it was ready to receive its cargo. The two massive iron doors were rolled back on rails to either side, and the water that dripped from the lip echoed as it fell thirty feet into the dark pit below.

Two Filipino ABSs leaning on the edge of the hold regarded the black-red interior impassively.

It was nothing more than an iron box, featureless except for a rusty spiral staircase winding its way up one wall, and scaling the other, a straight Australian ladder leading to the manhole that emerged on the deck. Soon both would be smothered under the hundreds of tonnes of loose trash that the crane was already spewing into holds one and two.

‘Fuck me, Efren. Where’d this shit come from?’

The smaller of the two sailors looked round lazily at the voice, with just enough animation in his body to avoid the accusation of insubordination. He grinned, and sniffed the air as if it was full of wind-blown blossom.

‘Come from Lima. Big pile. People live on it.’

Matthew Cotton felt like puking, helped of course by four double rum and Cokes, six shots of grappa and five beers; but mainly because the smell from the holds was so terrible.

‘Yeah? Well guess it ain’t a whole lot different to living in Queens.’

Though he hadn’t the remotest idea what his senior officer was referring to, Efren Ramos stood on one leg, smiled through gapped teeth and nodded. Matthew could have sworn they were going back to Port Arthur empty, but of course the suits at Sonstar would rather piss on their own grandmothers than have one of their ships burn fuel without earning cash. If they were struggling for a decent load of ore then he guessed the trash made sense.

Matthew didn’t give a shit. He was on his way back to his cabin to sleep this one off. Then he would get up in time for dinner and start work on a whole new stretch of drunkenness. That was what mattered. Keeping it topped up. Keeping it all nice and numb.

He turned with a flick of the hand that meant ‘carry on’ and walked unsteadily back to the accommodation block. The sun was getting low, but even so its heat was bothering him.

He wanted the shade of a cabin with the drapes pulled and the darkness of sleep, where for a few short hours nothing and nobody could reach him.

Darkness brought a sour breeze to the dock, and to the ship it brought a nightly invasion of mosquitoes that could not only locate every inch of exposed human skin, but even the fleshy parts of the countless rats that ran the length of their metal sea-going home.

Of course there were no rats on the Lysicrates. Every official form and inspection sheet signed and dated testified to that, claiming proudly that the ship was free from infestation. Indeed, that was what the circular metal plates ringing the top of the ropes were for, to stop the vermin boarding ship.

But there were rats. And on a ship this size, that meant there was plenty of room for them to carry on their daily, and right now, nightly, business.

The MV Lysicrates was 280 metres long, weighed a dead tonnage of 158,537, had nine holds and a crew of twenty-eight, all Filipino except for two.

Even in this bleak industrial Peruvian port, the three other ships that lay alongside her were doing so with considerably more dignity, for the Lysicrates transmitted an air of decay that was hard to prove in detail, but impossible to ignore in essence.

It was the feeling that everything that was necessary to keeping her working had been done so only up to the legal limit and not an inch beyond.

The paint was peeling only in places that didn’t matter, the deck was not littered with hazardous material that constituted an offence, but neither was it particularly clean, and the hull was dulled with variegated horizontal stripes of algae that clearly were not planned to be dealt with as a priority.

Its depreciating appearance was not unusual in a working merchant fleet, particularly in this part of the world, but it was nevertheless an unsightly tub.

She had been lying in Callao for twelve days, which pleased the lower-ranking crew who had been taking the train daily to Lima, returning with a variety of cheap and unpleasant purchases they imagined might curry favour with loved ones back home.

But the turnaround time was unusual. The Lysicrates worked hard for her living. Of a fleet of ten ships, she was the eldest, and sailing as she was under a Monrovian flag of convenience, she was hardly the most prestigious. The dubious registration meant that the company could avoid practically every shipping regulation in the book, and by and large, it did. While she was still afloat, the ship’s task was to sail loaded, as often and as quickly as she could, so the fortnight’s holiday in port was not normally on the agenda. But no one was complaining. And no one seemed to mind that the captain had spent an unusual length of the time ashore. All anyone cared about was that the holds were filling up and it was time to go.

Just as Leonardo Becko, the cook, was putting the last touches to a dinner of steak and fries, the door of the last hold of the Lysicrates was rolling closed with a rumble.

That would mean it was only a matter of hours, and the crew were already milling around above and below deck, making the comfortable and familiar preparations to ensure the constant uncertainty of the sea would once more be under their control.

As they did so, the cargo in hold two shifted its bulk as the strip of daylight that moulded its rotting undulations narrowed steadily with the closing door, and the two massive metal plates met, enfolding it in darkness.

What air remained in the three to four foot gap between trash and steel seemed to sigh as the finality of the doors being secured subtly shifted the pressure. And then the broth of waste that was as solid as it was liquid was alone in the dark. Locked in. Silent. Content with its own decay.

In the officers’ messroom, Captain Lloyd Skinner was already at his table, pouring himself a glass of water, when he caught sight of his female passenger walking past the open door.

‘Miss … eh …?’

Her figure moved backwards into the door frame. Esther had changed into a cotton shirt and jeans, and with her deeply tanned flesh scrubbed she radiated a health that was out of place in the atmosphere of mundane industrial toil.

‘Hi? Mulholland. Esther Mulholland.’

The man cleared his throat, and smiled. ‘This is where you eat.’

She looked down the corridor, to the open door of the crew’s mess hall where she’d planned on eating, already accommodating five silent Filipinos, smoking and waiting patiently for their food. Esther returned the smile and walked into the room.

There were three round tables set for dinner, empty, their glasses and cutlery polished and waiting for diners. The Starsky-and-Hutch interior designer had been at work here too, adding plastic pot plants to the garish patterned fabrics, affording the room the atmosphere of a sad waiting area in a run-down clinic.

‘Captain?’ She held out her hand but didn’t sit down, waiting to be asked. This was a different deal from the voyage out here. She had no passenger rights that normally elevated the ticket holder to the status of officers, only the good will of this man she’d never met, and Esther had an instinct for making herself worthy of good will when she needed to.

The man had an abstracted expression, his attention elsewhere. ‘Eh, yes. Lloyd Skinner.’

He took her hand without rising, shook it limply, moved the book he had been reading to one side as though it were in her way, then motioned in general to the three ugly plastic padded chairs beside him like a reluctant furniture salesman.

Skinner, she reckoned, looked to be in his late forties, perhaps even early fifties, but in direct contrast to his soak of a first mate he was in such good shape it was hard to tell. Whereas Matthew Cotton was probably only scraping the ceiling of his thirties, his hair had greyed prematurely, and his face was lined, brutalized, the flesh sucked from the bones by abuse, leaving him with the mask of a much older man. Skinner glowed with health. Sandy hair topped an oval golden-brown face with distracted blue eyes and a mouth that was perhaps a little on the thin side. He was powerfully built, and the arms that emerged from his short-sleeved shirt indicated that his body hadn’t always been behind a desk.

Esther gave an internal sigh of relief that at least the man in charge of this decidedly shabby tub seemed to be halfway human. She sat down happily.

‘I really want to thank you, Captain Skinner. I mean, this is way past kindness and out the other side.’

The man coughed into his fist while looking beyond her at the open door, then at the plastic plants.

‘No problem. These, eh, tickets, are pretty flexible.’ He gestured vacantly into the air and continued. ‘Merchant ships change their schedules all the time.’

Esther’s heart started to barnacle with lead.

‘Didn’t your first officer mention mine was non-refundable?’

‘Oh, we’ll sort it.’

‘No. I mean really. It’s a grace-and-favour ticket.’

The captain looked at her properly for the first time, and there seemed to be something akin to alarm behind his eyes. ‘You have family in the shipping line?’

Esther thought about Gerald McKenzie. Thought about his clammy hands on her breasts and his awful breath in her ear. Thought about him guffawing in the darkness of the theatre at the pathetic overwrought antics of Jim Carrey, his wet mouth full of popcorn. She gulped back a combination of revulsion and shame at how she’d used him, and like so many boys before, hadn’t let him use her like he’d planned.

‘No. No. It’s a friend’s father. He works for Croydelle.’

Skinner ran a hand over his jaw and neck and looked away again. ‘Ah. Well … whatever.’

There was an awkward silence, while Esther waited for some kind of confirmation that indeed everything would be all right, but was rewarded only by Captain Skinner looking down and touching his book absently as though he wished very badly to go back to it. She cleared her throat.

‘So will that still be okay?’

‘Mm? Oh yes. Yes. I’m sure. Your ticket. You can, eh, see the purser with it.’

He smiled weakly, then looked to a figure hovering by the door to the galley, more to avoid the awkwardness of this conversation, thought Esther, than out of an eagerness to be served. The glance, however, bore fruit.

A man in a stained white waiter’s jacket approached the table, handed them both a menu encased in a thick red plastic folder like that of a cheap diner, then disappeared again. Skinner straightened his arms and regarded the menu as though it were the printed fare of a state banquet.

Esther looked at the intent on his face and quickly reviewed her first impression. She ought to have guessed that no ordinary captain would employ such a drunk for his first in command, but the level of this man’s dismissive distraction seemed out of character for a man in charge of a large ship and sizeable crew.

The captain on the Valiant Ellanda had been a straightforward industrial boss, friendly, but very much in charge, his officers a reasonable selection of men doing their jobs and enjoying the limited social life at the end of their watches. That journey had been uneventful, the company boring, but the atmosphere comforting. This was disquieting. Esther glanced down at the paperback on the table, desperate to start a conversation that would at least engage him before he changed his mind about her free passage. She expected a Wilbur Smith or worse, the standard fodder of bored sailors, but what she saw shocked her, immediately halting the small-talk possibilities her brain was already preparing. He was reading an English translation of the Koran.

Esther looked from the book to the man and back again.

‘Are you Muslim, Captain Skinner?’

He looked at her for a moment as though she were mad, then blinked down at the book placing the thick menu gently alongside it. ‘Hmm? Ah. Ha ha. Good gracious no.’ He lifted the volume and looked at it as if for the first time. ‘Just working my way through the religions of the world.’

A small Filipino man entered the room, nodded to them both, showing no surprise at all at Esther’s presence, then sat down at another table and took out a book of his own.

‘Really? Some task,’ said Esther, quite genuinely intrigued and not a little impressed. She tried to force his eye contact back to her again by touching the book lightly. ‘You’re interested in theology then?’

Captain Skinner looked over at the officer engrossed in his own less contentious volume, a Filipino translation of some ancient Tom Clancy, then gazed absently again at the plastic pot plant.

‘Interested in the uniform stupidity of mankind.’ He looked back round at Esther coolly. ‘No offence of course, Miss Mulholland. If you’re religious yourself.’

She shook her head slowly.

‘Not at all.’

‘Then you might take my point.’

‘It’s certainly one view of spirituality.’

He smiled benignly as though they had been discussing the weather, then folded his hands neatly on the menu in front of him.

As the three expectant diners sat in a tense silence the Filipino man at the next table was joined by one other, and as if on cue the waiter appeared again, handed them both menus and shuffled to the captain’s table to take orders.

Esther endured the first course – some green wheatfloured soup – in miserable silence, listening to the two other men talking softly in their own language, occasionally laughing and nodding, enjoying an easy companionship. When the leathery steaks came and it became clear that her fellow diner had no intention of speaking, she decided it was too much. She was going to try again.

‘So where you from then, Captain?’

Skinner looked up as if he’d just noticed her. ‘Denver originally. Florida now.’

Esther beamed. ‘Gee. That’s a change and a half.’

He returned her smile without warmth, but the prompt seemed to work. ‘And you?’

‘Scranton PA, originally. Texas now. So guess I’m not one to talk.’

‘Ah. Hence no southern drawl,’ he said without interest through a mouth of fries.

‘Why I do declare I can manage when I try,’ said Esther in her best Pam Ewing.

Skinner ignored the burlesque but looked at her with renewed interest. ‘And you do what exactly there?’

Esther moved her food around a little with the fork to mask embarrassment at her failed entertainment. ‘College. Last year majoring in anthropology. This was my dissertation field trip.’

Genuine curiosity, the first she had noticed since their meeting, lit behind Skinner’s eyes. ‘Interesting. What do you hope to do with such a thing when you graduate?’

‘Well it’s a military scholarship. So I guess during the seven years of active service I’ll owe them after I qualify, at least I’ll understand people and their diversities of culture before I kill them.’

Skinner looked at her for a moment in stunned silence, then he put his big hands down on the table, threw his head back and laughed.

Surprised, but delighted at the reaction to such a feeble joke, Esther watched his face then joined in his mirth.

‘I guess we’re a lot alike, Miss Mulholland.’

And that was the last thing he said to her before he finished the remainder of his meal in cheerful silence, leaving her alone at the table to contemplate exactly how that similarity might manifest itself.

4 (#u0822ac7f-3760-5911-9571-db132baf9de4)

No matter what time of day or night it was, the accommodation block of the Lysicrates always housed someone asleep. Different shifts and watches meant the crew made their own day and night, and there was an understanding about noise and privacy that was delicately observed in the way that people living at such close quarters are forced to do. There were currently four bodies lying in their respective cabins.

The first officer was unconscious on his foam sofa, a crushed beer can held to his chest like a teddy bear. The second engineer was fast asleep in a neatly-made bed dreaming of his wife, and the sixteen-year-old deck cadet, the youngest of the crew, was snoring loudly on his back in a top bunk after having masturbated over a not-particularly-explicit porn magazine the cook had brought him back from Lima.

But although it was his turn to sleep, and with only another legitimate hour and a half in which to do so, Fen Sahg, a greaser and fireman, was wide awake. He had turned his back on the cabin in an attempt to avoid looking at the gaudy idols and 3-D posters his cabin mate Tenghis had fixed to every surface he could morally call his own. Even though he was staring fixedly at the white painted metal of the cabin wall, the image of Tenghis’s plaster Virgin Mary, her head inclined in pity, her white arms outstretched as though for his soul alone, was burnt into the back of his eyes. He knew the man only did it to rile him. They were both Catholics by upbringing of course, but Tenghis had taken exception to what he called Fen’s ‘wicked pagan superstitions’, and believed it was his duty as a good Christian to bring him back into the fold. It was true he was superstitious, but only with good cause.

Tenghis’s fears were hypocritical, since Fen knew only too well that Tenghis himself could have his moments too. They had both worried when two voyages ago the chief engineer brought his wife on the ship. Surely every sailor knew it was unlucky to have a lone woman on board. Two or three officers’ wives, well maybe that was okay. But one alone? No. And look what had happened. The cook had nearly sliced his little finger clean off during that storm south of Panama. There was no doubt amongst the lower-ranking crew who had been responsible for that. No, superstition was not always baloney and old women’s fears. But as to his wicked paganism, Tenghis was wrong too. To amuse his fellow crew members, Fen often held Saanti readings in the mess hall or his cabin, the method of prediction and revelation being an obscure Asian mixture of Tarot and ouiji. The Saanti showed him the truth of things, and he would be a fool not to pay heed. That didn’t mean he too couldn’t be a good Christian, and Tenghis’s sulk after such an evening, which would sometimes last for days, punishing his cabin mate by saying his rosary loudly in bed at random times, was a gross insult. But tonight it was not Tenghis’s irritating piety that was making him wakeful. It was thinking about the Peruvian stevedores.

Gossip in any port spread quickly, and Fen usually liked to help it along if it was juicy enough. So when there was a rumour that the stevedores were unhappy about the cargo of trash being loaded onto the Lysicrates, Fen was the first to make himself amenable to the gang chief to try and find out why. The chief was a small suspicious man from the country and it took a lot to befriend him, but since the ship had been lying here for so long, longer than any other vessel usually did, Fen managed by persistence to make the man take him into his confidence.

It certainly was an unusual load. The Lysicrates normally carried coal, iron ore or gravel, and even on other bulk carriers he’d sailed with he had never come across the bulk shipping of uncompacted domestic waste before.

And apparently he was not the only one to find it irregular, since there had been some kind of negotiation being carried on between the company and the dock authorities, which had caused the trash to have been sitting in a vast rotting pile in the dock’s loading area for nearly a week while Captain Skinner sorted out a bill of lading.

The rumours had started after two days. There were complaints about rats and roaches of course, but when a prostitute that visited the docks on a nightly basis had gone missing after servicing two of her regulars in her temporary boudoir inside an empty container, talk started that it had something to do with the trash. Fen couldn’t quite get from the man what he thought the connection was, but some names had come up, curiously none of them Spanish, but of a tongue he didn’t recognize, and there was a whispered uneasiness amongst the men about something one of them had seen in the great and stinking pile.

In itself this was merely the normal superstitious nonsense of simple under-educated working men, of which Fen was one, but he was more intuitive than most, and could usually distinguish the nonsense from the genuine mystery. What was bothering him now was that as he had watched the trash being loaded from the vantage point of the deck, Fen could have sworn he had seen something.

Rats probably, he reasoned, but then in fifteen years at sea, years when he’d seen just about every trick the repulsive vermin could perform in everything from grain to cocoa bags, he’d never seen rats undulate under a pile of anything in quite the way this grab-load of refuse had moved. If it had been rats, then there had been a lot of them, and working together. Because the surface of the junk had pulsated in a way that made him break out in a sweat. The thought of the rodents, however logical an explanation, was not in itself a particularly comfortable one.

Beasts that size that could move with such ordered intent were not beasts he looked forward to sharing a voyage with. But if the movement was not caused by rats, then Fen wasn’t entirely sure how he felt. A hot sensation had overwhelmed him as he’d witnessed the swift but substantial movement, and the unpleasant notion had swept across him that it was moving, revealing itself, for his benefit only.

Fen’s only consolation was that he had been so horror-struck by the sensation that he had made himself watch the grab drop the pile from a height into hold number two, monitoring it carefully as it fell, and could see all the individual pieces that made up the pile clearly revealed. Nothing alive and writhing had made itself visible against the bleached South American sky. No heavy rats tumbled and squirmed in the air, and neither did anything else.

Still staring at the wall, he turned over in his mind whether that was a comfort or not. Maybe the truth was that he never really saw the movement in the first place, that the talk of the stevedores had primed him with nervous expectations that his superstitious mind obligingly furnished.

Or maybe it was a simple trick of the sunlight and the unpredictable movements of the huge crane.

Fen sighed and turned back over in his bunk to look reluctantly at Mary.

This was not going to be a lucky voyage. First the girl passenger Cotton had brought aboard, and now the worry about what he thought he had seen. If sleep evaded him much longer he would get up and consult the Saanti. Then he would know.

The holy Virgin glared at him reproachfully. He would stare at her fixedly for the remainder of his rest period, because regardless of what his logic wanted him to believe, in his heart he knew there had been something moving in that trash. And whatever it was, it was now on board.

Adjusting the hard hat which was tipping over his eyes, Captain Skinner finished his leisurely perambulation of the long cargo deck, one hand in his pocket and the other holding the thin paper on which the details of the cargo were scrawled. He could see the second officer and the bosun leaning together on the rail, smoking and watching the dock hands mill about aimlessly on the harbour edge below them as they waited for the Lysicrates to go, and he detoured his route to join them. Instantly the bosun stamped out his cigarette and adopted a posture of readiness. The second officer made an upward nod of greeting and continued to stare down at the harbour. Skinner leant beside the officer and smiled past the two men at the lights of the port.

‘Reckon that’s us, Felix.’

The bosun smiled, nodded and left. Renato Lhoon, the second officer, tapped some ash overboard and looked up at his captain.

‘Chief Officer Cotton?’ enquired Skinner into the night air.

‘In cabin.’

‘Ah.’

The two men watched a cat dart surreptitiously along the edge of a wooden shed, spurred faster by a piece of coal thrown by the bored stevedore waiting to untie the ship. Skinner looked at his wristwatch.

‘Fifteen minutes.’

He smiled again at nothing in particular then left Lhoon to figure out what was required. It didn’t take much figuring. The second officer sighed, flicked his cigarette over the edge, tucked an errant shirt-tail into his neat pants, and walked toward the door of the accommodation block.

The door opened onto C-deck, the living quarters of the crew’s lower rank, and to advertise the fact, the hand rail outside each cabin sported a motley selection of garments ranging from socks to grimy T-shirts airing in the hot corridor.

An elevator served the decks from the bridge down nine floors to the propeller shaft in the engine room, but Lhoon decided that to stand and wait for it to chug and shudder to his command from wherever it happened to be, would give every passing cadet and ABS the opportunity to bend his ear on some gripe or other, and frankly right now, with the task of waking Cotton before him, it was the last thing he needed. He climbed the metal stairs without enthusiasm two floors to the officers’ accommodation deck and walked slowly to the door of Cotton’s cabin. As usual he tried the handle first, and as usual it was locked.

He coughed into his fist, then used it to bang the door twice. There was no reply. He banged again.

‘Matthew? Come on.’

A groan from within gave strength to the next bout of hammering, which Lhoon kept up relentlessly until he heard the groggy voice again.

‘Fuck off.’

‘We go now, Matthew. Your watch.’

‘Sail the fucker yourself, Renato.’

Lhoon started to bang with both fists now, and kept it up until the metallic snick of the lock being thrown rewarded his efforts. The small man stopped his assault on the door, turned the handle and entered. The cabin was in darkness save for the orange-and-white light of the deck filtering through the thin porthole curtain, and he flicked the switch behind the cabin door.

The lights of Matthew Cotton’s cabin revealed that at least tonight Lhoon would not have to dress him. He was lying back on the sofa again, fully clad, his arms across his face as a shield against the sudden glare. As far as the officers’ cabins were concerned, Cotton’s was no different in design. One room with a seating area and coffee table, a bed riveted to the wall and a half-open door leading to a shower room with WC.

What marked his out as unusual would not be immediately apparent to a casual observer, but to any sailor it was glaringly obvious. Unlike every other cabin on board the ship Matthew Cotton’s was the only one that was completely devoid of family photos. Even the youngest cadets, barely out of school, and the filthy and objectionable donkeyman whose mother would find him hard to love, had photos, framed or otherwise, of sweethearts and family adorning every possible personal space of their quarters. Nothing in Cotton’s cabin revealed anything about who might occupy his most intimate thoughts or longings. Apart from a few piles of clothes and shoes that cluttered the floor, more than a few empty beer cans that filled the wastepaper bin or sat redundantly on the table top, nothing suggested there was any sign of a man living here, that this was a private space in which a man could recreate part of his shore world on board.

Lhoon stood with his hands on his hips above the recumbent figure and waited. ‘You want to puke first?’

Matthew’s voice was muffled behind his arm. ‘Yeah.’

Lhoon waited some more, knowing that even the suggestion would spur his senior officer’s guts into action. A moment later Matthew raised himself up from the sofa, stumbled slowly through to the shower room and bent to his work over the sink. The noise made the second officer catch the back of his throat and he swallowed and looked away.

‘I wait or you done?’

‘Done.’

Matthew ran the tap and stuck his head under it, and after a moment of recovery walked through to join his colleague for the routine escort up to the bridge, and for the duration of the short walk Lhoon let Matthew walk in front, a guard escorting his prisoner to the gallows.

Apart from the fax machine behind Matthew, droning as the weather report rolled through, and the ghostly, muffled voices on the radio that he had turned down to a dream-like volume, the bridge of the ship was quiet.

Before him, the hold deck looked almost glamorous, illuminated as it was by pinpricks of white light, and framed by glimpses of the white ocean foam the stern was pushing aside.

Matthew ran a rough hand over his face and sat down heavily on a chrome stool that wouldn’t have been out of place in a New York bar. They were well clear of port now, and there was nothing to do for the next four hours except stare at the darkness ahead, and drink neat vodka from a china mug that declared ‘Swinging London’ on the side beneath a garish Union Jack.

He’d planned to be asleep again before the end of the watch, but that didn’t matter, since Renato would come and check on him every twenty minutes and do anything that needed doing. But nothing would. He’d pointed the tub for home and that was it.

This was the worst watch for him, the long hours of darkness, with nothing, no distractions, no human company, no chores or excuses to think, to keep him safe from his own black interior.

He’d tried reading at first, but his mind wandered after the first two paragraphs, his eyes scanning the meaningless words as other images replaced the ones conjured by the invariably bad authors, and with considerably more impact. So now he just sat and stared. And of course, drank.

Tonight the vodka bottle was behind the row of chilli pepper plants that Renato grew in plastic pots along the starboard bridge window. It was only habit that made him hide it. Skinner didn’t care and there was little need for deception, but it was an important part of the alcoholic’s ritual to conceal, and ritual was all he had left. He drained his mug, walked to the plants, retrieved the bottle and poured another big one.

Matthew fingered one of the swelling fruits and smiled at Renato’s dedication. A storeroom below groaning with fruit and vegetables, and yet the man lavished attention on these scrappy plants as though all their lives depended on it. The nurturing instinct. As strong in some men as it is in women. With the thought, a black ulcer threatened to burst in his heart and he turned quickly from the fruits, swallowing his vodka as he walked quickly back to the desk.

With a shaking hand he fumbled through the folder of paperwork. Something to do was what he needed. He’d pretend to be a first officer. At least until the demons receded. Read about the cargo. That would work. The part of him that was still alive had been intrigued that loose trash was being loaded. It was a cargo he’d never come across. Compacted metal, industrial waste, sure. But domestic loose trash from some city site? Never. It would be interesting to see where it came from and more importantly where it was going.

Matthew skimmed through the piles of paper recording every on-board banality from crew lists to duplicate galley receipts, but there was nothing. No bill of lading, no sheaves of inspection certificates from the port authorities, no formal company documents with tedious instructions and warnings.

He found some dog-eared cost and revenue sheets that had been used practically unchanged on the last three trips. They told the company, the shipping federation, the world, that the Lysicrates was going home empty as planned. The ship contained nothing but ballast water. He blinked down at the paper and then stupidly out the window to the silent deck.

Presumably Skinner hadn’t finished doing whatever he did so privately in his office with all that paper before entering it in the log and the document folder, but it was unusual, and unlike the captain’s usual form, very sloppy.

You could load anything from custard to cows at Callao if you greased the right palms, and from the eleven voyages he’d made so far with this company, Matthew had decided they were perhaps not amongst the most honourable of traders. Forever trying to dodge regulations they’d even lost a vessel five years ago with all hands, and had despicably argued about compensation to the families of the deceased for as long as they could, even though the insurance company had paid up in full. Shysters and crooks, and naturally the only ones who would employ someone like Cotton after his fall from grace, although Skinner, he admitted reluctantly to himself, had had more to do with his second chance than the avaricious gangsters who owned the ship. But if the company was pulling some kind of a fast one, what in God’s name were they planning to do with the trash when they got to Port Arthur? For a few moments the slow, drunken brain of Matthew Cotton thought about it. He let himself think like a captain again, think about the nature of loose trash, of how it would sit in the hold, how it might shift in weather. Gradually, as his brain cleared more thinking-space, he thought of methane gas building up like a bomb in the sealed holds, and the consequences of that when the hot South American sun hit the deck from dawn and started to bake it like a desert stone. A tiny sliver of rage started to build in his chest. Tiny but insistent. If he could die he’d be dead a thousand times by now. Dying was too desirable, too good for Matthew Cotton. It was a release he didn’t deserve. It wasn’t up to the slimy suited bastards in the Hong Kong offices of a shipping company to change that.

He glanced at the weather fax again, which he’d already registered indicated nothing but fine weather. Then he picked up the phone and called down to B-deck.

A deck cadet answered in Filipino.

‘Rapadas. Open all the hatch covers fifteen feet.’

The man didn’t even reply, but several minutes later two men walked lazily into the white light of the deck and started working the hydraulics that would wind open the huge metal doors, slapping each other on the shoulder and continuing some animated conversation as they worked their way along. For a moment Matthew almost felt like an officer in charge. Someone who’d taken a responsible and intelligent action to prevent disaster.

But the moment was brief. Reality hit him and reminded him he was nothing higher than pond scum. He sank down again and drained his mug. The holds wouldn’t blow. The ship and the crew would be safer now than they were twenty minutes ago.

Big fucking deal.

The sun would come up and go down. The earth would turn. Stars in space would die and be born. And nothing he ever did, good or bad for the rest of his life would make him anything other than a piece of shit. Swinging London tipped up and Matthew Cotton’s eyes closed. His free hand made a tight claw on his thigh.

5 (#u0822ac7f-3760-5911-9571-db132baf9de4)

The fantasies of most ancient cultures almost always included one of walking on water. From Christianity through Mayan domestic legend, even into modern obsessions with surface-bound sports, the defiant, burnished skin of the ocean presents a challenge to man that is considerably deeper than the mere domination of nature.

As the early morning sun gave the Pacific a pale cream solidity, Esther felt she could run straight off the deck and onto that glittering rugged surface without puncturing it. However, a dull but well-meaning officer on the journey down to Callao had regularly and unbidden furnished Esther with sea-going statistics, and the revelation that the sea along the coast of Peru concealed a trench that was over twenty thousand feet deep had induced in her an immediate vertigo as she thought of the blackness yawning beneath her feet. Gazing out now at the innocent shining surface, she felt that same mix of fear and thrill again at the ocean’s secret.

Maybe, she reasoned, that was why mankind always felt impelled to make instant contact with water the moment it was anywhere in his vicinity. The child on the beach who runs without fail to the sea, the adults who pull off their socks and shoes to paddle in the shallows, the fisherman who catches nothing but is satisfied with the contact of weighted line and water; all are reassuring themselves that what excites them about what they see, that beckoning seductive sheet of light, is as flimsy as net and as dangerous as fire.

If she could, Esther, too, would have made contact with a cool sea.

A swim after the punishing circuit she was pounding would have been delicious, but even if the boat were a pleasure yacht that drifted to let her bathe, she wouldn’t care to swim thinking of the sunless chasm that lay beneath her. A cramped, steamy shower would do and with only four more laps of the cargo deck to go, even that was pretty damned attractive.