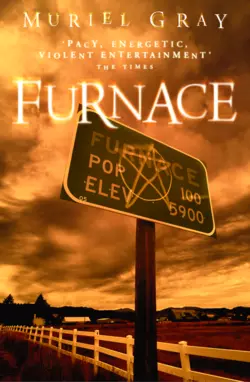

Furnace

Furnace

Muriel Gray

From the author of The Trickster, an unnerving tale of latterday alchemy and the horrors brooding beneath the placid surface of life in one small town in America.

Something is being born.

The darkness is its delight, deep and black and hot.

Its growth is unstoppable.

It knows who has summoned it.

It knows that its carrier is aware and afraid.

Its time is drawing near…

When long-distance truck driver Josh Spiller pulls into the small backwater town of Furnace, Virginia, he has a lot on his mind. He’s been driving for thirty-six hours straight after busting up with his pregnant girlfriend; he’s tired and hungry, and all he wants is to get some breakfast and rest up.

But Furnace has something special in store for Josh. Amongst the surprisingly affluent houses, the neat streets and smartly-dressed townsfolk lurks the stuff of living nightmare. A sequence of events is about to be unleashed that will test Josh to the edge of his endurance. A world of sorcery and malice is waiting to gather him in. For behind the prosperity of Furnace lie terrible secrets; and a terrifying fate in store for those who take an unwarranted interest.

Even now, as Josh searches for a place to stop, his electric-blue Peterbilt roaring through the gears, the eyes of the town are upon him.

The nightmare is beginning…

MURIEL GRAY

Furnace

HarperVoyager an imprint of

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk (http://www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2015

Copyright © Muriel Gray 1997, 2015

Cover photograph © Wiskerke/Alamy

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Muriel Gray asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008158255

Ebook Edition © December 2015 ISBN: 9780007582051

Version: 2015-10-29

For Hamish, Hector and

Rowan Marsaili Barbour, with love

Contents

Cover (#u2c46d54c-f9af-5218-8a7e-3003c1fa00ac)

Title Page (#u5aa950f8-a0c6-546e-af31-5ece3d18e9df)

Copyright (#u7a3d0667-bfd7-5794-9da9-eb098de753fc)

Dedication (#u3f060ad1-ea7c-5052-83e0-3e0afa616bfe)

Chapter 1 (#u3bdb8439-6d0f-553a-8f44-05584847ba94)

Chapter 2 (#u32a7167f-9f91-5bc6-9a59-0a5d6488c14f)

Chapter 3 (#u6f333517-7072-5beb-ac16-c38933ee8130)

Chapter 4 (#udb1de8a8-0fa4-5587-9c5a-5417c0cc17c2)

Chapter 5 (#u1d88ae5d-9818-59f9-acd3-66a61f9537d3)

Chapter 6 (#u988caf08-34af-5c7e-a197-c9989173d989)

Chapter 7 (#u1b21a10c-bd19-5f4e-89e4-18c3bef22606)

Chapter 8 (#u8a4a81e1-42bc-5ea5-969e-a001ca46b448)

Chapter 9 (#ucd2c97b9-aa24-5964-b250-18a644b81f77)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

The Ancient: Chapter 1 (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also By Muriel Gray (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1 (#u71bff44d-69f8-523b-ac8d-f80f0d79299a)

There was no need for her nakedness. Not yet. But as she stood on the rock and looked at the pale hands stretched out before her, she was glad that she had shed her clothes. The dawn light would break over the mountain behind her at any moment, and although the cold was fierce, her shivering was of anticipation rather than physical discomfort. The chill breeze on her skin felt good and the heavy scent of dogwood blossom and wet grass filled her nostrils.

Far below in the dark sweep of the Shenandoah valley, the lights of isolated trucks and cars moved along the highway as though pulled by an invisible link. She opened the fingers of her right hand and moved them across the blackness until they cupped one of those moving lights like a firefly. Perspective. It was incredible to her that it had taken the human beings until the Renaissance to interpret size and the distortion of distance correctly. What did ancient man think when he held up his hand as she was doing now, perhaps to balance a herd of animals on his palm? Did he think that by the visual evidence of their diminished size he became their master? And what made that thought more obtuse than the beliefs of modern man? To his eye, this would be no more than a naked woman standing alone on a hillside, playing an optical conjuring trick that allowed a truck to drive across her opened hand. How long before the next Renaissance-like awakening of intelligence? The awakening that would confirm his mistake in this respect.

As she became aware of the first rays of the new sun back-lighting her hair, she closed her hand slowly and obliterated the lights of the far-distant vehicle from her view.

‘Hey, Peterbilt. You got the four-wheeler leg shot ahead of you?’

Josh Spiller smiled before thumbing the CB in response.

‘Might do. Might not. How you gonna get that crawling piece of junk past my rig an’ find out?’

There was a cowboy whoop from the radio speakers, and as Josh had guessed, the source of the message was the reefer coming up on his left, increasing its speed and pulling level with him. He glanced with measured amusement at the cab of the Freightliner Conventional. It was like he thought. A company truck. Company drivers. A name ‘Kentucky Meat and Foul’ was painted on the door in fat blue letters, and the leering bearded face of the team driver hovered above them at the window, like he was a painting and the letters below spelled his title. The guy gave Josh a triumphant surfer’s thumb and little finger, accompanied by a shit-eating grin as his partner at the wheel came on the radio again.

‘Come on there, big truck. Bet you snatched a look at the snatch. Am I right, or am I right?’

Josh rolled his eyes skyward, trying hard to suppress a smile, then looked forward again.

To his right, the great rolling back of the Appalachians was a graceful black cut-out against the lightening sky, and in only a few minutes the first orange arc of a new sun would break across that heavenly silhouette. But to the guys on his left, the sun could come up accompanied by a cloud of naked golden angels sounding trumpets, and all they’d do would be to slap their thighs and guffaw at the fact that they could see some flying bare ass.

He felt a sudden wave of sympathy for the girl in front, still oblivious to the harassment she was about to endure. Channel 19 had been discussing her for the best part of an hour. Sure her legs were long and her skirt short, though if she hadn’t left her interior map light on no one would have known. But the bumper sticker on the back of her tiny Honda, that line-drawn fish that declared the driver was a Christian, suggested that light being left on was an innocent error. In Josh’s experience Christian ladies didn’t flash truckers.

His sympathy was mixed with a strange nostalgic melancholy brought about by the imminent appearance of the sun. He’d been feeling pretty mellow for miles, looking forward to slotting a cassette into the stereo and watching the dawn break over the mountains to the sound of something good. Something carefully chosen to heighten the privileged experience of welcoming the daybreak over gentle but beautiful open country. Now these pencil-dicks had ruined it, and there was nothing he could do. They would get level with her, probably sound their horn and embark on a series of gestures among which a zoologist could find subject matter for a dissertation.

As they inched forward, the reefer struggling to get ahead of Josh’s more powerful rig, he sighed and resigned himself to the spectacle, running a hand over the back of his neck to massage away fatigue from the muscles there.

And then the red light winked.

Josh glanced up at the radar detector on his dash and as quickly across at the cab of the reefer.

Company trucks didn’t carry radar detectors. Other owner-operators like Josh might just. The damned things were illegal in big trucks but nobody could get you for just riding with one, and Josh knew where to switch it on and where not to. Here, on this stretch of the northbound interstate through Virginia, he was glad it was on. If nothing had changed in the highway patrol’s routine since his journey down, then he knew exactly where those bears with the radar were. There was a rest area just ahead on the right before the next exit, and that’s exactly where he’d spied a state bear sitting hunting on the way southbound only three days ago. How could the apes in the Freightliner know that? They couldn’t. Not without a detector, or that other essential lifeline every trucker relies on. Information from a fellow driver. A driver like Josh. And if Josh chose not to say anything, there weren’t a whole lot of trucks packing out this road right now who’d blow those bears’ cover instead. The highway was so quiet it could have doubled as a runway. On the dash the red light was going crazy, and Josh pressed simultaneously on his brakes and the talk button of the CB mike, a smile nearly cutting his face in two.

‘Yeah, you’re on it, guys. I looked for sure. And let me tell you, she’s askin’ for it. Since she been showin’ us so much leg there, why don’t you fellas give her a look at some of them Kentucky chicken pieces of your own.’

He looked across as the cab of the Freightliner started to pull away by virtue of his own subtle braking, and watched the bearded guy slap the dash and give a thumbs up in appreciation of the joke.

‘Come on, asswipes,’ Josh whispered as he saw the rest area up ahead.

The truck drew level with the Honda, and as the window of the Freightliner started to wind down he could just make out the nose of the patrol car, peeking out from behind a clump of scrubwood, still expertly hidden from anyone who wasn’t looking for it. Josh’s smile couldn’t get much wider, but he tried.

The timing was close to perfect. The Honda swerved a little as two fat white buttocks poked out of the Freightliner’s window, a finger sticking grotesquely into its own rectum, precisely as the three vehicles glided past the parked patrol vehicle. To the two cops sitting glumly in their car, wishing that dawn would break and bring the end of their shift closer, it looked like a circus act that had taken a lifetime to perfect. They exchanged no more than a brief and weary glance before snapping on the siren and pulling out.

Now it was Josh’s turn to slap the wheel in glee as the Freightliner edged back and pulled over, falling prey to the police car like an antelope brought down by hyenas. Josh was alone with his good Christian lady again, and part of him wished she had CB so he could share the joke, and more important so that she could thank him for his betrayal of colleagues in the name of chivalry. But the exit ahead seemed to be the one she wanted, maybe from choice, or maybe just to get off the highway and away from her persecutors. She started to brake and signal. Josh braked in response and was surprised when she slowed to a crawl. There was nothing for it but to pass, so he swung the rig out and changed down accordingly. As the bulk of the Peterbilt moved past the woman’s tiny car, now peeling away at a snail’s pace towards the exit ramp, Josh Spiller threw a look across at her.

From her open window an elegant arm emerged in farewell, and on the end of that arm, stabbing the air repeatedly like it was trying to puncture an invisible skin, was a deeply un-Christian middle finger.

He’d fumbled in the plastic ledge above the dash for a good thirty seconds, initially finding only an evil knot of Jelly Bellies that had fused together in the heat of the cab, before his fingers closed on the cassette he wanted. The sun was almost visible now, and Josh urgently wanted to get his chosen track lined up before it was too late.

He flipped the tape out of the plastic junk-filled canyon and slotted it quickly into the stereo. It came on halfway through some terrible and elderly Doors number. Wrong. So wrong he wished he’d never included the track on this jumbled and hastily assembled compilation. He pressed fast forward, waited and then let it play again.

Aerosmith. He cursed silently. That meant that it was rewinding, not going forward.

The sky to his right was now growing light so fast that a ridiculous mixture of anxiety and frustration tightened his chest. He took out the tape and reinserted it. The machine didn’t like the way he did it and slid it back out at him again. The sky had now gone way past pink, turning into the luminous aquamarine that heralds the first glorious golden shards of sunlight, as he slammed the troublesome cassette back in and pressed fast forward again. Two pauses and he was there.

Josh couldn’t say why he fancied this track most to greet the dawn, but he did. It was old but it was tranquil. A song off some weird album by a British band called The Blue Nile that Elizabeth’s kid brother had loaned him.

It started with a slow drum then this really sad guy came on and sang like he would break your heart. You had to be in the mood or you couldn’t take it. Josh was in exactly the right mood. It was just what he wanted for the big event, the arrival of the sun after this nine-hour non-stop homeward haul from Tennessee. And it was going to work this time. It was going to be a peach. The track was lined up, the sun was maybe only seconds from view, and he was northbound in the right lane with nothing obstructing his view across the dew-soaked fields to the dark rolling back of the Appalachians.

That was important to the full enjoyment of the moment, the absence of anything man-made in between him and the sunrise. No buildings. No human junk. Nothing that would spoil his view with another reminder, particularly after his disappointment in the reluctant maiden he’d rescued, that sometimes people didn’t deserve another day graced by anything as beautiful and indiscriminately benevolent as the sun. He waited, his hand ready to press play, glancing every three or four seconds out of the passenger window to catch the first sight.

Up ahead, the highway stretched empty before him, an artery of stone that fed America its life-blood. Or was it a vein that circulated the disease of man and his junk around the once untouched and healthy body of this delicate continent?

Josh gazed out front, contemplating it for a second, knowing that whatever the answer, he was a part of it. The rare sight of clear road made him suddenly feel exposed, an alien object moving without permission upon an ancient and secretive landscape.

And in those few moments of inattention as Josh dreamily regarded the road ahead, the sun betrayed him and sneaked up over the rim of the hills. He whipped his head to the east as the first orange beam hit the side of his face, shifted in his seat and stabbed the play button on the stereo.

The tape hissed and then the song began.

How could he have known? Even with the benefit of the height that he enjoyed from the truck Josh couldn’t see the entire landscape ahead, couldn’t see the mark of man that was waiting for him, nestling smugly between mountains and highway. So at that religious and significant moment when the sun rose, it rose not over unsullied meadows and hills, but from behind a forest of four tall masts, one tipped by golden horns, another by the Cracker Barrel sign, the other two proclaiming Taco Bell and Burger King.

Josh blinked for a second, his mouth slightly open until an excited voice on the CB crackled over the gentle song playing on the tape and brought him back.

‘Man, oh man! Any of you northbounds see that?’

Josh glanced across at the source of the enthusiastic message; a lone R-Model Mack pulling a covered wagon on the southbound highway.

Gratefully, Josh picked up the handset. ‘Sure as hell did, big truck. Glad there’s someone else out there with a soul.’ He flicked off the tape, ready to receive the reply, and it came right back at him with its enthusiasm intact.

‘Yeah? Man, I can’t believe they’s only askin’ two dollars ninety for a chargrill, family bucket of fries, soup and a free soda. That’s a whole dollar less than the joint at exit 19. Sure gonna work for me!’

Josh Spiller stared ahead for a second or two, then gently replaced the handset, let out the remains of his breath and started to chuckle. He shook his head and carried on laughing until a tiny rogue tear rolled down one cheek and he wiped it away with the back of a greasy hand.

‘Shit. Know what, America? You are one fucked-up country.’

2 (#u71bff44d-69f8-523b-ac8d-f80f0d79299a)

She’d been awake for at least two hours. Now that the dawn was bleeding through the drapes, she shifted under the covers and ran a hand over her warm belly. She had to get up. No choice. But here, in the dark that was gradually being corrupted by light, it was safe and warm to think, and everything outside that cocoon seemed impossibly cold.

Josh’s face. She closed her eyes and thought about it. Sometimes, if it had been a long time, she had trouble remembering the exact contours. But even if it was difficult to visualize she could always recall how it felt beneath her lips. She held on to that now, breathed in through her nose as she thought about the smooth soft skin over his cheekbones, the thick curl of eyelashes and the rough texture of bristle around mouth and chin.

With her eyes still shut, she swung her legs out of the bed and sat up.

The bedroom mirror greeted her with her own reflection when she raised her head and looked towards it. Despite her hunched posture, even she would admit that her breasts looked enticing. They were fuller and firmer than she’d realized, and her hands came up in an unconscious gesture to cup them gently.

Elizabeth Murray let her hands move up to her face and then spoke in a whisper to the mirror, the delicate planes of her cheeks and forehead sculpted by the grey dawn light.

‘What now?’

Josh waited impatienly outside the phone booth. There were only three private booths at this Flying J truck stop, all occupied by frowning men who looked like they were making talking an Olympic event. He sighed and leaned heavily against the wall, toying with his Driveline calling card.

The big black guy next to him was holding the phone against his ear with his shoulder, passing a rubber ball restlessly from hand to hand as he listened, his eyes glazed like he was hearing bad news.

Josh guessed what he might be hearing. The guy’s dispatcher would have put him on hold, and the profound expression of misery was most likely induced by an age of listening to the theme from Love Story reproduced electronically by a sadistic phone company. He looked at his boots. All he wanted to do was to call Elizabeth and tell her he was less than an hour from home. No filthy talk like you sometimes heard and wished you hadn’t, but he wanted privacy when they spoke, and if he didn’t get a free phone soon he’d miss her. He’d already gone past that delicious time when she would pick up the phone beside the bed and answer in a sexy, sleepy way. Right now she’d have a mouth full of Cheerios and be pulling on a jacket ready to go to the store, pleased to hear from him, but with a tone of urgency in her voice that meant he was making her late. Five more minutes and she’d be gone.

The door of the centre booth opened but infuriatingly the guy hadn’t stopped yakking.

Josh made a move towards him and the guy held up a hand without looking at him.

‘Uh huh? Well it ain’t okay with me.’

A listening pause.

‘No, it ain’t my last word. This is my last word. Okay, two words. Fuck you.’

He slammed the phone down, got up off the small plastic seat and pushed past Josh.

Josh grinned at him, and gesticulated at the phone. ‘It’s a drag always havin’ to call your grandmother, ain’t it?’

The man looked for a moment like he might throw a punch, but something in Josh’s eyes held his clenched fist by his side, and he satisfied himself with a ‘Yeah, funny guy’ muttered beneath his breath.

Josh smiled at the man’s back and entered the booth, his grin deforming into a grimace at the blush of sweat those substantial buttocks had left on the plastic. But he needed to make that call. He decided to stand, and as he punched in the code for the card he shook his head. Seemed like all truck drivers did was drive and then get mad with someone for no other reason than they didn’t like driving.

Choose any truck stop, any row of phones and mostly all you’d hear was a chorus of deeply discontented men. Some of it was just plain moaning, but enough of it was from the heart to make hearing it uncomfortable. Why drive if you hated it so much? Josh liked it fine. Just fine. And he loved Elizabeth. If the seat was clammy with his sweat after he’d talked to her, it wouldn’t be from stress.

The vacant computerized woman on the phone thanked him in a monotone for calling Driveline and informed him in a voice that suggested she was painting her nails that he had seven dollars and fifteen cents left to make his call. He punched in their number.

It rang eleven times and just as he was about to hang up Elizabeth came on, out of breath, and sounding angry.

‘Yeah?’

‘Hey. You should get into telephone sales, honey.’

She tried to change the tone, but there was still something there. Something at the back of her throat.

‘Hey yourself! Where are you?’

‘On the pike. Near enough home to smell next door’s mutt.’

‘Well get back here. I missed you.’

It was familiar small talk. But she said the last bit as though she really meant it.

‘You okay?’

‘Sure.’

‘Big day, huh?’

‘Yeah. Big.’

A melancholy tone reaffirmed that something was wrong. Now, in this tiny booth with two guys already waiting outside, wasn’t the time to find out what it was.

‘Want me to come straight by the store?’

‘How you going to park Jezebel?’

‘Normally I just pull on the brakes and shut her big ass down.’

‘And screw the Pittsburgh morning traffic?’

‘For you I’d leave her standin’ in the middle of the Liberty Tunnel at five-thirty Friday night.’

She laughed, and hearing her was like he’d swallowed something warm and sweet.

Elizabeth sounded more like herself when she spoke next. ‘Then come on by and make a traffic cop’s day.’

‘See how it goes.’

‘Love you.’

‘Love you too.’

He hung up and left the booth. Had he imagined it or had she really sounded uneasy? Understandable. Today, she and Nesta started their new career. A sackload of tasty redundancy pay blown on their crazy business.

Josh would have spent it buying something a man could use, like a decent flat-bed to switch with the trailer he was pulling so he could haul bigger sections of steel when he needed to. But it was Elizabeth’s choice, her money. She didn’t spend much of his, and he certainly didn’t spend any of hers.

Fifteen years as a machinist hadn’t made her rich but facing a new day, every day, sewing nylon umbrella sleeves, cheap bags for storing shoes and suit covers, had given her plenty time to think about her life. She and her buddy were about the only girls not weeping when the scrawny, acne-covered floor supervisor told them they were out. With a little shame, Josh admitted to himself that he didn’t really know if the costume ball hire shop was Nesta’s idea or Elizabeth’s. But he sincerely hoped the name ‘All Dressed Up’ was Nesta’s. It was seriously crap.

Of course Elizabeth would be scared today. The door would be opening in a couple of hours for the first time, and she’d be praying, fruitlessly Josh thought, that there’d be a queue of customers round the block, ready to part with cash to dress up in the ridiculous costumes she and Nesta had been sewing for the last three months.

Costume balls baffled him. To Josh, the idea of standing around at a party with a beer in your hand talking to someone about real estate or kit cars seemed pretty attractive. But not if you were dressed like Pinocchio and the guy you were talking to was trying to make an earnest point in a fun-fur kangaroo suit. But if it made money, then so what?

What bugged him was that Elizabeth’s tone had sounded more than just anxious. Sounded like she was sad.

He wandered out of the phone lobby and through the shop towards the restaurant. Maybe he should buy her something.

Truck stops nearly always boasted carousels full of junk that skulked near the cash desk like muggers, offering a variety of garbage for the guilty driver to take home and pacify his sweetheart. But until now Josh had never really looked at it.

The days when he’d done things he’d have to say sorry for were the days he hadn’t had someone steady like Elizabeth waiting at home. Now he had her, he didn’t do much on the road except drive, eat, sleep and shit.

Pausing for the first time at the cylindrical stand like it was a confession box, Josh let an embarrassed gaze drift over the assortment of tacky merchandise. He found himself looking quizzically at some round balls of fluff with eyes and feet made of felt, sporting cloth ribbons that said everything from ‘I Love You’ and ‘You’re Cute’ to statements of coma-inducing inanity like ‘I’ve been to West Virginia’. A gentle push of his forefinger sent the display turning slowly round to reveal badly-made plastic boxes covered in lace hearts that had been hastily glued to the lids, and some dusty-looking dolls dressed as cowgirls.

Josh glanced around, anxious in case anyone had seen him looking at this stuff, only to discover the woman behind the counter already had. She smiled when he caught her eye. Maybe someone had given her one of those fluffy balls once, with a message on the ribbon that she wanted to hear. He lowered his eyes, and wandered casually over to the display of Rand McNally road atlases, flicked through a couple like he’d never seen a map of America before.

Men like Josh Spiller didn’t look right poking at dolls and lacy boxes. Six feet and one hundred and sixty-eight pounds of fit, pale body were topped by a head of light brown hair cut so short it was near enough shaved. There was a tiny silver ball of an earring in his right ear and it combined with the hair to make sure he didn’t get stopped in the street often by nuns collecting for orphanages. What little hair that had survived the cut sat above a face with kind blue eyes, a straight, elegant nose and a wide, mischievous mouth. That open face meant that although he was adopting the demeanour of a mean guy, no one was going to mistake Josh for a member of an underground militia group. He looked kind. He couldn’t help it. Nevertheless, the spirit in him that made him look the way he did was not prepared to let him stand at the counter and buy some piece of girlie shit. He shut the atlas and walked towards the restaurant.

‘We got something new over here she might like.’

The woman behind the counter was smiling, her eyes lowered, looking at what she was doing and not at him. Josh cleared his throat.

‘Yeah?’

Her fat fingers counted out shower vouchers in front of her like they were cards in a game.

‘We got these real pretty pins. All sorts. And a machine that does her name on it while you grab a bite. Takes about ten minutes.’ She indicated the contraption behind her with a small movement of her shoulder. ‘You just turn that there dial to the letters you want and it gets right on doin’ it. Seventeen dollars including the name. Plus tax.’

Josh was trapped. He walked slowly over and she looked up.

From behind the glass under the counter she took out a tray of cheap pewter-coloured metal brooches shaped in a bewildering variety of little objects, each with a space beneath the object for the name like the scroll on a tattoo. With his hands in his pockets Josh looked them over, grateful the store was empty.

There were tiny metal bows, a rabbit, some bees round a hive, all in a mock-antique style, and all waiting to have a woman’s name scratched beneath their immobile forms. Despite his discomfort he decided they were cute and when his eyes wandered over to one made from a tiny pair of scissors cutting out a perfect metal heart, Josh knew Elizabeth would like it. The scissors were neatly appropriate.

‘So you do their name on the blank bit with that machine?’

‘Well I ain’t doin’ it. Got enough to do keepin’ you guys from rippin’ me off to sit here and carve your wives’ names on a pin.’

Josh smiled, pointed at the one he wanted and reached for the wallet in his back pocket. ‘Okay. It’s Elizabeth.’ He spelled it for her, watched her write it so she wouldn’t make a mistake, then went to get that coffee.

‘Takes ten minutes,’ she reminded him to his back as she clicked the letters into something that looked like a sewing machine and with her tongue sticking out the corner of her mouth placed the brooch on a tiny vice.

3 (#u71bff44d-69f8-523b-ac8d-f80f0d79299a)

Elizabeth was right. There was no way he could park Jezebel anywhere near the store. In fact, there weren’t many places in downtown Pittsburgh you could take an electric-blue Peterbilt Conventional with a sixty-inch sleeper and forty-eight-foot trailer. Not unless you wanted to end up trapped like a beached whale, snared in some narrow street by four-wheelers who park like the whole world is their front drive.

Instead, Josh drove straight to Jezebel’s parking lot ten miles out of town, did his paperwork, zipped up a week’s worth of stinking laundry and headed home in the pick-up. He figured Elizabeth wouldn’t really want to see him in the store anyhow. Not if she was busy measuring someone up as a giant tomato. Right now, he needed some sleep. He’d be more use to her wide awake, showered and ready for action.

The duplex that Josh and Elizabeth shared was nothing special, but it was on a quiet block with tiny neatly-trimmed gardens tended by peaceful neighbours. Josh owned the whole house but rented the lower half to an elderly Korean bachelor called Sim, a tiny man in his seventies who constantly complained that he was at the rim of death’s abyss, usually while in the yard tending patio pots full of unpleasantly pungent spices and herbs.

Today was no different. Sim was sitting on a canvas stool against the wall of the house in the chill morning sun. A cigarette hung from his tight mouth, and he held The National Enquirer at a distance from his face as though he were a doctor examining an important X-ray.

Sim looked up as Josh’s pick-up pulled into the yard, and by the time Josh had climbed out the old man’s face had changed from a lively interest in his paper to one of silent suffering.

‘How it been this time, Josh?’

Josh knew the routine. He liked Sim.

‘Good. Seven days, four loads. Pays the rent. How you been?’

This was how it always went.

‘Oh I not got long now, you know. I had pains. Real bad. Right here.’ He indicated his chest with the flat of a palm.

‘Maybe you ought to give up those smokes, Sim.’

‘They not problem, Josh. Living the problem. Too hard for me sometimes. Know how that is?’

Josh nodded. ‘Sure do.’

He continued to nod his head gravely as though Sim had pronounced a universal truth, but by the time he was through the door and the old man had returned to reading about the secrets of Hollywood’s bald stars, Josh was grinning. Life didn’t look too hard for Sim. But then life wasn’t too hard for him, either. Josh was thirty-two years old, and for ten of those he’d been hauling everything you could name, and some things you couldn’t, from one corner of his country to another.

Now, in particular, things were pretty good. His wild years had passed when he’d driven team, swallowing anything and everything illegal to keep awake for forty or more straight hours on the road, just like all the other guys who were trying to make a living. Four years ago he’d joined the world of grown-ups, got a bank loan and bought his own rig. Josh was up to his neck in debt, with the bank’s shadow looming over his house and his truck. But running his own tractor unit and trailer, even just having his name painted on the door in curly purple fairground writing, made him feel like a man who had done something useful every time he stepped up into Jezebel. It wasn’t just driving any more. He worked like a dog, he had a business, and it felt okay.

The house reflected that small triumph. The kitchen he walked through from the yard door was Elizabeth’s domain, full of silly calendars and photos stuck to the ice-box, dried flowers in baskets on top of the cupboards and plaid drapes swagged to the side of the windows that would never meet if anyone were bold enough to undo the huge bows that restrained them and try to draw them shut.

But in the spare bedroom that Josh had made his office, his life in the rig came back with him into the house. It was this room he headed for first, ostensibly to check if there were any faxes or messages on the answering machine, and flick through the mail that Elizabeth left in tidy piles on his desk. The truth was that the room was an airlock, a halfway stage to reacclimatize himself into a life that wasn’t really his; that of wandering round shopping malls, going out for dinner, drinking beer with friends in their yard or his, or just watching TV while Elizabeth fixed their meals.

All the ordinary stuff that most people did and thought nothing of, Josh had to relearn every time he pulled on the brakes and came home. At least in this room, with its giant map of the states pinned unevenly to a cork wall, piles of correspondence, trade magazines and bits of scrap paper that related only to his driving life, he could come down gently, ease into Elizabeth’s normality and try to make it his own. For a few days at a time, at least.

The fax stared back at him, insolently exposing the emptiness of its horizontal slot, and the mail was equally unrewarding. Just bills and a few late cheques from companies that paid slowly. He flicked through them with mild disappointment, the constant hope when returning home to a pile of mail that something in it would be surprising and life-altering, dashed again. Josh left the room, took a shower and crawled into their flowery linen nest for the first sleep of home. The difficult sleep. After six nights stretched out in a sleeping bag on Jezebel’s sagging foam mattress behind the cab with dozens of truck engines thudding outside, finding oblivion in this big, fresh, soft and silent bed took time.

This morning it couldn’t be found at all. Josh was weary, but closing his eyes brought nothing but the road rolling by on the inside of his lids. He lay in the bed, his hands behind his head, resigned to sleeplessness, content with merely resting in a state of semi-reverie until Elizabeth came home, when he hoped she would slide into the warmth and join him.

Josh remained motionless but wakeful for several hours, sufficiently relaxed to be unaware of the day as it played out its variations of light behind the closed bedroom drapes, but then he was a master of rest without sleep. Driving created a new gear for the mind, a neutral that demanded little of the body except breathing. It was almost trance-like and he’d driven in such a state plenty of times, despite the plain reckless danger of it. His enjoyment of the escape it afforded was broken by the sound of Elizabeth’s key in the lock, and the slam of the screen door. He opened his eyes, surprised to have dreamed what seemed like the entire day away, then stretched and lay back with his eyes closed, waiting in delicious anticipation for her to come to him, knowing that she’d see his pick-up parked outside and realize he was in bed.

It was comforting, hearing her sounds, the clatter of domesticity, as she moved about in the kitchen, opening and closing cupboards, putting away things she must have bought on the way home, and the scrape of a chair as it was pulled out from the kitchen table. Josh waited.

There was silence.

He slid his legs reluctantly out of the warm bed, pulled on a voluminous sweatshirt and yawned. As he made for the door he remembered her gift, fished in his jeans pocket and transferred the small box into the pocket of the sweatshirt. Then he made his way through to the kitchen, scratching at his skull like a bear.

She was sitting at the table motionless, her back to him, her head turned towards the small window. Elizabeth had hair that was only marginally longer than his own, but the cut was feminine and accentuated the graceful sweep of her neck. He leaned against the door-frame and drank in the slender architecture of her shoulders.

She turned and looked up at him. Brown eyes in a pale and almost masculinely handsome face looked as if they wanted to return his heat, but they were clouded with a film of defeat.

Josh put out his arms and she stood up and moved into them. With an almost imperceptible sigh of pleasure he allowed his fingers to part the dark hair and caress her head.

‘Bad?’

She nodded against him with a tiny movement.

Josh put his mouth to the top of her head and spoke into her hair.

‘Hell, they just don’t know what lucky is, Pittsburgh folk. The chance to zip themselves into a chicken suit, right here on their doorstep, and where are they all?’

‘Fuck off.’

She mumbled it into his chest but he could tell it was said through a smile. He lifted her head and made to kiss her, but her smile died as she looked into his eyes. Then she pulled free.

Josh put his now-empty arms up in a gesture of surrender.

‘Joke.’

‘I know.’

She sat back at the table, where he joined her and took her hand.

‘It’ll pick up. Just one guy who gets his rocks off at a party dressed as a pirate and tells his friends, believe me, you’ll be beating them off with shit-covered sticks.’

‘You’ve been gone a long time.’

An accusing tone she never used. It threw him, and he withdrew the hand that had been covering hers.

‘Got an extra load from Louisville. Couldn’t turn it down. I told you.’

‘We need the money that bad?’

‘Yes.’

She looked down at the table.

‘Sorry.’

His hand was still on the table top. Avoiding his eyes she slid her hand over and laid it on his. Josh reached into the sweatshirt pocket with his free hand, took out the small box and slid it towards her.

‘For you. It’s dumb but it’s for luck.’

She looked up and met his eyes, a smile beginning to ghost in them again.

‘You been screwing someone?’

‘I wish.’

She opened the box, rustled the piece of tissue paper and revealed the dull metal brooch. Her name was etched clearly but unevenly on it, with the E too far from the L and the final T and H crammed so tightly together they were practically one letter, but Elizabeth took the cheap gift from the box as if it were a Fabergé egg.

‘This is beautiful.’

‘It’s just junk. I thought you’d like it.’

‘You thought I’d like junk? That’s what I call romantic.’

She was smiling full on again. For Josh, the brooch had already proved hundreds of times its worth.

‘You like it?’

‘I love it.’

‘Well wear it and things’ll look better tomorrow.’

Her face clouded again and she toyed with the brooch, making a scraping sound on the table as she shifted it around.

‘Maybe.’

Josh held the bridge of his nose between a finger and thumb.

‘What’s the deal here? I’ve been gone longer and you’ve said less.’

‘I had things to talk to you about, that’s all.’

‘Well talk to me now.’

‘It’s too late.’

Josh sighed and bent his head. ‘Shit, Elizabeth. You’re acting like a teenager whose prom date hasn’t shown. I’m kinda tired here.’

She looked at him coldly, stood up, still clutching the brooch in her hand, and walked to the sink to stare out the window.

Josh watched her face as she turned back to him, and saw some kind of battle being fought behind those brown eyes. One of the emotions eventually won and she spoke softly, as if ashamed of its victory.

‘I’m pregnant.’

Josh blinked. He was aware that his heart had picked up its pace, but if that meant more blood was suddenly required and being provided, its rapid distribution seemed to be having little effect on him. It was as though his system had stalled like a smoky engine, leaving him temporarily unable to speak or move. He searched for the kick-start, and when he found it and spoke merely for the sake of speaking, realized that he should have waited.

‘Is it mine?’

Elizabeth’s face, already harder than he had ever seen it, darkened into the suburbs of fury.

‘I’ll give you one chance to take that back.’

He swallowed. ‘Shit, I’m sorry … I mean … Fuck.’

She regarded him with a mixture of contempt and grief. The same eyes that only minutes ago had looked up at him like a lover were now scouring him with acid accusation.

Josh tried again. As he got up to move towards her she made him jump with a sudden violent movement, lifting her arms and waving them in front of her as if to protect herself. He backed off, hands held out in an imploring gesture, and his voice, when it came, was higher than he would have liked.

‘I didn’t mean that. I don’t know why I said it. I’m glad. God, Elizabeth, I’m so glad.’

With those words something happened to Josh Spiller. A happiness that was beyond any he had ever experienced flooded into him and he realized that ‘glad’ was a weak and sickly word to describe the power of his sudden ecstasy.

Elizabeth watched the face of the father of her child as it exploded into rapture, watched his tense muscles melt into a slack, serpentine tangle of joy. Her lip trembled like a child’s as she braced herself. Then she spoke quickly to interrupt the acceleration of his emotion: ‘I’m not keeping it, Josh.’

His imploring arms fell.

‘What?’

‘I don’t have a choice.’

Josh looked at her for a very long time, then turned back to the table and sat down heavily on his chair. He leaned forward and cradled his head in his hands, his hot forehead pointing straight down to the table top.

‘Now hold up. This is going too fast. Talk to me.’

Elizabeth looked down at a hand which had become a fist, and when she opened it to reveal the brooch she had been clutching she could see two clear indentations that the scissors had made in her flesh. She closed her hand.

‘You weren’t here to talk to. I decided on my own. It’s impossible, Josh.’

He looked up from the cradle of his hands.

‘Why? For Christ’s sake we’re doing okay. Aren’t we?’

She swallowed back a sob, barely able to speak.

‘Nope.’

‘What do you mean?’

Elizabeth moved stiffly and rejoined him at the table. She stared into the yellow pine as though the words she was speaking were printed on it.

‘Commitment, Josh. That’s what a baby needs. It’s what I need too and I’ve never had it from you in any shape.’

He opened his mouth to protest but she silenced him with a sorrowful look.

‘I’m not complaining. This is an accident in a relationship that’s doing just fine. But it’s a relationship that can’t handle children.’

She was sounding rehearsed, but seven days to perfect a speech hadn’t been enough to stop it sounding phoney.

‘Welcome to daytime TV, folks.’

The bitterness in Josh’s voice was as alien to him as it sounded to Elizabeth. Any plan she might have had evaporated, and she looked at him like a frightened child.

‘Look at us, Josh. We live together but we’re not married. I see you for two, maybe three days out of every ten. I’ve just started a new business that needs all my time and energy. There’s nothing in this dumb life of ours that’s stable enough to make a good job of growing another human being.’

‘We love each other.’

‘Then why aren’t we married? Why aren’t you at home?’

‘Why aren’t you? Is sewing fucking Batman suits better than staying home and looking after our baby?’

She looked at him coldly. ‘Jesus Christ. You can take the man out of the truck but you can’t take the trucker out of the man. What next, Josh? The chorus of a Red Sovine song?’

He lowered his eyes.

‘I didn’t know you wanted to get married.’

‘You never asked.’

‘What if I asked now?’ His voice had an edge of desperation.

‘It would mean nothing. You wouldn’t be asking for the right reasons.’

There was a pause. A heavy silence that made Josh’s response startling.

‘FUCK!’

He slammed his fist down on the table so hard that Elizabeth leapt in her chair and caught her breath with the fright. Josh was breathing heavily, staring down at his hands, and she spoke softly when her heart had stopped pounding.

‘Next week. Wednesday at three o’clock. It’ll be over.’

He looked up slowly and her grief was almost uncontainable when she saw the film of tears that coated his eyes.

‘Then why even tell me? Does it feel good to give me a few moments of joy and then steal them back again? Huh? Make you feel big? Feel in charge? That what you call love?’

Elizabeth started to cry. Her chest heaved and she bent her head to her chest. Josh watched, wanting instinctively to comfort her but cancelling the order from his brain before it reached his arms.

She sobbed for a few minutes in silence, wiped her arm across her eyes and nose and then faced him again.

‘I told you because I was scared and lost. I always tell you everything.’

He looked at her tragic, puffy face and tried to feel the love for her he knew was there. But the imminent death of his baby, that terrifying appointment, the time already ticking away towards its execution as the baby’s cells split and multiplied inside her, was blocking it like a wall. He spoke quietly and with a malice he never knew he possessed.

‘You didn’t tell me you were a selfish bitch.’

Elizabeth stared at him for a moment, stunned.

‘Damn you to hell.’ She opened her hand and with all the force a close sitting position could afford, threw the brooch at Josh’s face and ran from the house.

As he sat still, listening to her car start and screech hysterically from the drive, Josh fingered the tiny scratch that his gift had inflicted above his eye. He bent to pick up the fallen weapon and closed his hand on the brooch’s innocent form.

There was no question of what action to take. He would do what he always did in a crisis. Josh Spiller got up and went to call his dispatcher.

4 (#u71bff44d-69f8-523b-ac8d-f80f0d79299a)

Time. It was at the core of everything. To buy it. To control it. To comprehend it. And yet still, this night, this eve that had been so long coming, so long anticipated, had now crept up on her like a thief.

As always, she tapped three keys on the keyboard and watched the figures scroll up the screen. She knew what she would see, but it was important to remind herself why.

This was why. The golden, glimmering, shining reason for it all. The dollars, the deutschmarks, the pounds, yen and lire, all flickering before her, lighting her face up with their green glow.

More. The knowledge and power.

But no. She closed her eyes and clenched a fist against it. That thought was forbidden. Vanity was destruction. The power was in the humble and respectful use of the knowledge. And that was why tomorrow was no more and no less than the necessary function that it had always been. The others depended on it. Their world turned on it, because God made it possible. She moved the mouse and closed the file with one diagonal sweep and click, as the sound of soft spring rain tapping at the window won the battle for her attention over the buzzing computer.

And she smiled as she looked up, imagining it soaking new buds on the blanket of trees that separated her from the dull uncomprehending mass of humanity.

It had taken the surly teenagers in the loading bay over an hour to load his trailer. And that was after a two-and-a-half-hour wait in the damp Victorian warehouse. Josh had sat in the drivers’ waiting area, cradling a styrofoam cup of stewed coffee, watching the three bozos wandering around his truck like pimps on a Bronx street. One drove the fork-lift into Josh’s trailer and the others hung around the doors making flipping gestures with their hands and adjusting their baseball caps as they laughed about something secret.

Normally, Josh would have gone out and kicked their butts, but this time he sat immobile behind the glass partition, watching them waste his time. It was a shitty load, some metal packing cases for an industrial ceramics manufacturer in Alabama. No weight in them, so not much pay. But it was all he could get, and Josh would have delivered the Klan’s laundry to South Central LA if he’d been asked. He would have taken anything at all just to turn off and buy his ticket away from home.

There had been two other drivers in the warehouse and, hold the front page, they had been bitching:

‘So I grabs this little jerk by the collar and I says okay man, you want me to load it myself then you gonna have to tell your boss why his lifting gear got all bust up, ’cos I ain’t never used it afore. ’Course I have, but he don’t know that.’

The guy who’d been telling the story was about as big as his truck and the other driver listened without much interest, waiting for his chance to tell a similar triumphant story of how he showed them, and showed them good.

‘Well he calls me everythin’ but a white boy and then I just grabs hold of the controls and lets the whole bunch drop twenty feet onto the deck. Hee hee, did that boy load up like his dick depended on it.’

Josh had let the stream of familiar bullshit wash over him. He was numb. So numb, he’d uncharacteristically ignored both men, walked to the trailer when a nod from one of the rubber-boned kids indicated it was done, barely checked the load or how it was stacked, taken the paperwork and driven off. And now he was sitting upright, staring out of the darkened cab of Jezebel, whose bulk was untidily taking up most of the space in a southbound tourist parking lot on this Virginian interstate. He’d driven for only a couple of hours, but a lapse of concentration that nearly let him trash a guy on a Harley Davidson had made him catch his heart in his mouth and pull over.

It was two a.m. and he could hardly account for the last eight hours since Elizabeth had driven away with her, and his, precious cargo on board. He stared ahead into the dark, sitting in the driver’s seat with his hands resting in his lap like a trauma patient waiting to be seen in an emergency room. Josh wasn’t thinking about what to do. He wasn’t even thinking about Elizabeth and where she might be right now. All that was running through his mind were the words, repeating themselves like a looped tape, ‘How do I feel?’

Soft spring rain started to fall, gradually muting the intermittent roar of the traffic on the adjacent highway. He wound down his window and breathed in a mixture of mown grass, diesel fumes, and the dust raised by the rain from the parking lot’s asphalt. As he tried to take a deeper breath he felt a vice tighten around his chest, a crippling tension which prevented that satisfying lungful of oxygen. The pain came not from the emptiness that was left by that brief and grotesque argument, but from the dual seed of joy and dread that was still germinating in his heart.

Wednesday the seventh of May, three o’clock.

What was it? A boy or a girl? He hadn’t even asked Elizabeth how many weeks old her secret was. A bizarre omission, but more confusing was why he wanted this child so badly. Some of the things Elizabeth had said were true, he knew that. Their life wasn’t exactly an episode of The Waltons, but until last night he’d thought it was safe and stable. It was an adult life, where two self-contained people did what they pleased and came together when they wanted. He’d never even considered how or why that might change. Never considered a third person entering the frame.

The fresh air stirred him from his miserable torpor and Josh got up, absently pulling the drapes around the inside of the windshield. He climbed back into the sleeper and lay down on the mattress with his hands behind his head.

As he lay there, staring up at the quilted velour ceiling, he allowed himself to think of her, of Elizabeth; that funny, sometimes brittle person who even in her hardest moments could be melted like butter over a stove with a kind word or gentle touch.

It was like her to carry the burden of her news silently, but it was unlike her to taunt him by telling him it was over before it began. Perhaps he didn’t know Elizabeth at all. Who was that terrible mixture of defiant accusation and self-pitying grief? And who had he been, to call her what he did and withdraw the support he’d always given unthinkingly and unconditionally?

Josh screwed his eyes tight, trying fruitlessly to squeeze the scene into oblivion with the puny muscles of his eyelids.

Which coupling had done it, he wondered? Last week? The week before?

When?

Outside, a car pulled up in the lot and Josh opened his eyes to listen to the familiar human noises of a man and a woman as they left their vehicle to go and use the rest-rooms.

They chatted in low voices, in that comfortable intimate way that meant they were saying nothing in particular to each other, but were enjoying saying it. An occasional short laugh broke the flow of their small talk as they slammed their car door shut and their footsteps receded towards the rest-rooms. Josh realized he was listening to this most mundane collection of sounds with his teeth clenched and his eyes narrowed, the invisible couple’s easy happiness an unbearable affront.

He lay there for a very long time, and as time ticked away, bringing neither sleep nor solution, he was aware of its swift relentless passing for probably the first time in his life.

Dawn on the first of May was less beautiful than the one Josh had tried to savour yesterday. Low clouds masked the sun’s coming and a thin grey light was all that announced the day. He had lain sleeplessly in the same position all night, eyes staring up into the dark as he alternated between thinking and hurting, and now he wanted to move. The load was already late. The paperwork promised the packing cases would be in Alabama sometime tonight, but they wouldn’t be.

Josh crawled from his bunk into the cab, opened the door on the new day and went to wet the wheels. As he stood, legs apart, urinating on his truck in some unconsciously atavistic ritual, he reconfirmed with himself that the best cure for any form of unhappiness was perpetual motion. Driving let him escape. It allowed him time completely on his own and freedom from responsibility. It had certainly saved his sanity when his mother died, that hellish two weeks after her funeral, when Josh knew he would never again have the chance to say the things to her he’d rehearsed so many times alone in his cab. He’d left his morose brother Dean at their empty home to go through their mother’s pathetically few things, accepted a load to Seattle, and pushed the thought of his loss out with the opening of his log book.

He recalled seeing his brother’s grief-torn face accusing him through the dirty upstairs window as he drove off, and it had chipped at something hard inside that Josh thought had been impermeable. Five hours later he’d put the whole thing out of his mind. Dean had never really forgiven him for that act of abandonment. But he didn’t understand. No one but another trucker would.

Josh finished his task, did up his pants, then leaned forward to rest his forehead against the side of his trailer and punch its aluminium flank with the side of a fist.

‘Fuck ’em all, Jez. Fuck every last one.’

5 (#u71bff44d-69f8-523b-ac8d-f80f0d79299a)

The cloud had lifted as she stood rigid and still on the grass. That was good. She watched the thin sunlight play amongst the bare branches of the ancient tree that stood solemnly in the wide street, and as her gaze moved down to the base of its massive bole, she frowned with irritation. There were suckered branches starting to form in clumps at the base. That meant only one thing. The tree was dying.

It must have been the men laying the cables last year. They had been told to make sure the trench came nowhere near the roots, to cut a path for the thick mass of plastic tubing and wire in between those delicate arteries of soft wood rather than through them. But they were like all workmen. Lazy. And this was the result.

She ground her teeth and concentrated on fighting the irritation.

Absence of malice, absence of compassion, absence of all petty human emotion. It was essential.

In a few hours she would let her thoughts return to the vandalized tree, but not now. The workmen would never be employed by her again. And that, she decided, would be the least of their worries.

But not now. Push the thought away and leave nothing. Nothing at all.

Quarter of an hour down the highway, Josh saw a five-mile service sign and realized he was hungry. More importantly, he was approaching his thirty-sixth hour without sleep and unless he grabbed a coffee soon, bad things were going to start happening. In fact, they already had. A dull grey slowness had settled on him, making his peripheral vision busy with the hazy shifting shapes that severe fatigue specialized in manufacturing, and his limbs were beginning to feel twice their weight. But hungry as he was, he still hadn’t forgotten the affront of yesterday’s dawn. McDonald’s might have sold ten billion, but he wasn’t going to make it ten billion and one.

He thumbed the radio.

‘Any you northbounds know a good place to eat off the interstate?’

The voice first to respond just laughed. ‘Surely, driver. There’s a little Italian place right up ahead. Violins playin’ and candles on every table.’

Josh smiled.

Another driver butted in. ‘No shit? Where’s that at again?’

‘I’m kiddin’, dipshit. Burgers ain’t good enough for you?’

Josh pressed his radio again, then thought better of it. What did these guys know? Channel 19 would be busy now for the next hour with bored truckers arguing about the merits of the great American burger. He was sorry he had started it.

There was an exit coming up on the right, and although the sign declared this was the exit for a bunch of ridiculously named nowhere towns, he braked and changed down. It was twenty before seven and if he didn’t get that coffee soon he’d have to pull over.

The reefer tailing him came on the radio.

‘Hey, Jezebel. See you signalling for exit 23.’

Josh responded. ‘Ten-four, driver. That a problem?’

‘Got a mighty long trailer there to get up and down them mountain roads. They’re tight as a schoolmarm’s ass cheeks.’

‘Copy, driver. Not plannin’ on goin’ far. Just grab a bite and get myself back on the interstate.’

Josh was already in the exit lane as he spoke the last words, the reefer peeling away from him up the highway.

‘Okay, buddy. Just hope you can turn that thing on a dollar.’

‘Ten-four to that.’

‘How comes she got the handle Jezebel?’

Josh grinned as he slowed down to around twenty-five, on what was indeed, and quite alarmingly so, a very narrow road. When he felt the load was secure behind him, he took his hand off the wheel to reply.

‘Aw this is my second rig, and I figure she tempted me but she’ll probably turn out to be no good like the last one.’

He swallowed at that, hoping the ugly thought that it had stirred back into life would go away. The other driver saved him.

‘Yeah? What you drive before?’

Irritatingly, the signal was already starting to break up. Strange, since the guy was probably only two miles away, with Josh now heading south-east on this garden path of a road.

‘Freightliner Conventional. Everything could go wrong did go wrong. Might be mean naming this baby like that. Hasn’t let me down yet. But she’s pretty, huh?’

The radio crackled in response, but Josh didn’t pick up the driver’s comment. It was the least of his worries. He saw what the guy meant. The road was almost a single track. If he met another truck on this route they’d both have to get out, scratch their heads and talk about how they were going to pass. Josh slowed the truck down to twenty and rolled along, squinting straight into the low morning sun that had only now emerged from the dissipating grey clouds, to look for one of the towns the sign had promised.

The interstate was well out of sight, and he was starting to regret the impulsive and irrational decision to boycott the convenience of a burger and coffee. The road was climbing now, and since the exit he hadn’t seen one farm gate or cabin driveway where he could turn the Peterbilt.

He pressed on the radio again.

‘Hey, any locals out there? When do you hit the first town after exit 23?’

He waited, the handset in his hand. There was silence. It was a profound silence that rarely occurred on CB. There was always something going on. Morons yelling, or guys bitching. Drivers telling other drivers the exact whereabouts on the highway of luckless females. There was debate, there was comedy, there were confidences shared and tales told. All twenty-four hours a day. Anything you wanted to hear and anything you wanted to say, was all there waiting at the press of a button.

But here, there was nothing. Josh looked up at the long spine of the hills and reckoned they must have something to do with the sudden stillness of the radio. It unnerved him. The cab of a truck was never quiet. Usually Josh had three things going at once: the CB, the local radio station, and a tape. Elizabeth had ridden with him a few times and could barely believe how through the nightmarish cacophony he not only noted the local traffic report, but also hummed along to a favourite song, heard everything that was said on the CB, and was able to make a pretty good guess at which truck was saying it.

‘How in hell do you do that?’ she’d breathed admiringly after he’d jumped in with the sequel to some old joke someone was telling, only seconds after he’d been shouting abuse at a talk radio host who’d used the word ‘negro’.

‘What’d you say, honey?’ he’d replied innocently, not understanding the irony when she laughed at him. She said after that, if she had anything important to tell him, she’d do it over a badly tuned radio with a heavy metal band thrashing in the background.

Except she hadn’t. Had she?

It had been important, and she’d told it to him straight, her words surrounded by a proscenium arch of silence. Josh flicked his eyes to the fabric above the windshield where Elizabeth’s cheap brooch was pinned. He’d stabbed it in there as a reminder that it had been bought with love but used as a spiteful missile, hoping it would harden him to the thought of her every time the pain of their argument germinated again. But it wasn’t working. It just made him think of her long brown fingers fingering it with delight. Josh wished the trivial memory of her riding with him hadn’t occurred to him, hadn’t made him feel like his heart needed a sling to support its weight.

He leaned forward and retuned the CB as though the action could relegate his dark thoughts to another channel.

Still nothing.

Josh sat back and resigned himself to the blind drive. The next town could be two or twenty miles away, and he was just going to have to live with that. It could be worse. The road was still climbing, but at least it was a pretty ride.

Dogwood bloomed on both sides of the road and on the east verge the rising sun back-lit the impossibly large and delicate white flowers, shining through the thin petals as though the dark branches were the wires of divine lamps. Ahead, a huge billboard cut rudely into the elegance of the small trees. The sign was old and worn, with the silvery grey of weathered wood starting to show through what had once been bright green paint.

‘See the world-famous sulphur caves at Carris Arm. Only 16 miles. Restaurant and tours.’

In the absence of anyone to talk to on the CB, Josh spoke to himself.

‘World-famous. Yeah, sure. The Taj Mahal, the Grand Canyon and the fuckin’ sulphur caves at Carris Arm.’

As if he needed it, the sign confirmed that Josh Spiller was driving around in the ass-end of nowhere, and he was far from happy. If that was the next town, then sixteen miles was way too far. He started to weigh his options. Surely there would soon be a farm gate or a clearing he could turn in. But as the truck climbed it seemed less and less likely. The mountains were a serpentine dark wall, clothed here in undisturbed forest only just starting to leaf, and neither farmland nor building broke the trees’ unchallenged hold on the land. Josh had already driven at least four or five miles from the interstate and the thought of another sixteen was making him consider the possibility of backing up and turning on a soft verge, when without any warning or apparent reason, the road started to widen.

A house, set back in the trees, neat and spacious with the stars and stripes flapping listlessly on a flagpole by the porch, appeared on his right, followed by another three in a row almost identical a few hundred yards further on. No backwoods cabin these, but substantial suburban houses with trimmed gardens and decent wheels parked out front. Josh raised an eyebrow. This was what truckers called car-farmer country. The backwoods of the Appalachians were home to a thousand run-down trailers and cabins, sporting a statutory dozen cars and pick-ups half buried in their field, like the hicks who’d left them there to rot were hoping their ’69 Buick would sprout seeds and grow a new one.

Even on the main routes, Josh had been glared at by enough one-eyed crazy lab-specimens lounging on porches to know that this wasn’t exactly stockbroker belt. The kind of tidy affluence quietly stated by these houses was a surprise. But it was a welcome surprise to a man who needed his breakfast and wouldn’t have to buy it from a drooling Jed Clampit with a shotgun raised at his chest.

So half a mile and a dozen or more smart houses later, it was with relief that Josh hit the limits of the town to which these uncharacteristic middle-class dwellings were satellites. He drove past the brief and concise metal sign with a smile.

Furnace.

The wide street was now lined on either side by houses only slightly smaller than those on the edge of town. Standard roses bobbed in the breeze and hardy azaleas and forsythia were beginning to form islands of colour in a sea of smooth lawns.

It was five before seven and although it was early, people were about and Josh was heartened by the town’s potential for hot food to go. A kid rode past on a BMX, a sack of papers on his shoulder; two guys sweeping the road stood jawing against a tree, brushes in hand; a woman walking a dachshund on a ludicrously long leash stopped and waved to someone out picking up their paper from the front step. It was cosy, affluent, peaceful and ordinary. But it certainly was not what he had expected high up in this backwater of Virginia. Here, Jezebel felt ridiculously out of place, rumbling self-consciously through the street at little more than running pace, as though lack of speed could hide the bulk and noise of the Leviathan. The quiet street waking to its new day was like any other, but the affluence and suburban smugness was starting to jog a memory in Josh he didn’t like.

The Tanner ice cream sign.

A dumb, irrelevant memory, and one he tried to sideswipe. But it was there.

That ice cream sign.

For Josh as a child it stood at the corner of Hove and Carnegie like a religious icon; a circular piece of tin with the advertisement painted on it, supported at two points by a bigger circle of wire on a stand that let it spin in the wind. Judging by the arthritic squeaking of its rotations, it had stood at the end of his street like that for years, that dismal street his mother had brought them up on, a strange juxtaposition of the classes that Pittsburgh boasted, where the unwashed poor lived only a block away from their bosses, separated by no more than just a strip of trees or a row of stores.

Or an ice cream sign.

The Tanner girl and boy had big rosy cheeks and were licking the same cone of ice cream, vanilla topped with chocolate sauce. But when the wind blew the sign would spin and the picture, identical on both surfaces except for the children’s mouths which were closed on one side and open on the other, would animate into a frenzy of darting, licking tongues. Dean thought the sign was kind of spooky, especially when the wind was strong and the tongues went crazy. But Josh liked it. He liked it because it marked the beginning of Carnegie Lane, and more importantly, the end of Hove Avenue, an end to the crowded street that contained their tattered house. In Carnegie the houses were elegant and tall, keeping watch over their own spacious gardens with the demeanour of large wealthy women sitting on rugs at a race meeting. And unlike the regiment of dreary wooden houses that included the Spillers’, every one was different. Some were brick with wide white columned porches tangled with wisteria and honeysuckle. Others had stone facades and glass conservatories, or European affectations of mock battlements and balustrades. And in addition to the neat front lawns that were uniformly green all the way to the sidewalk, each, Josh knew for sure, had generous and private back yards.

School, the stores and everything that Josh needed to service his uneventful life was at the eastern end of Hove. In other words there was no call to go west into Carnegie at all. It merely led to wealthier parts of town, parts that were decidedly not for the Spillers. But he’d lost count of the times he’d found himself strolling past the squeaking Tanner ice cream sign, stepping into Carnegie with a roll to his pre-pubescent gait that tried to say he lived there.

At least he had until one searingly hot August. Josh was eleven and the day had been long and empty. His mother’s return from her job at a drug factory, moving piles of little blue and white capsules along a conveyor belt all day with a gloved hand, had been a cranky and irritable one. Particularly since she discovered that neither Dean nor Josh had made any attempt to prepare supper, but had instead been throwing stones up at the remains of an old weathervane that clung to a neighbour’s roof, in a contest to free it finally from its rusting bracket.

Joyce Spiller had sat down heavily on the three car tyres piled by the back door they used as a seat, and glared at the boys, but particularly Josh, with tired, rheumy eyes. Her voice was full of sarcastic venom.

‘Sure do appreciate you workin’ all day long, Mom. So to thank you for that act of kindness, please accept this cool glass of lemonade and a big juicy sandwich that me an’ my shit-for-manners brother have had all friggin’ day to prepare.’

Dean had blinked at his boots in shame, but for some reason, looking at this woman in her short nylon workcoat, her thin brown hair tied back with a plain elastic band, and her face that looked ten years older than her numerical age, Josh had suddenly despised her. Why should he look after her, when other kids got to come home from school and be met by a Mom who’d fetch them lemonade and a sandwich? What kind of a raw deal was this, having a mother who worked all day, sometimes nights too, who was always in a foul mood and looked like shit? The absence of a father, a taboo subject in the Spiller house, was bad enough, but the fact that they lived in this shambolic house and never went on vacation was all this failure of a woman’s fault.

Josh had stared back at her with contempt and then run from the yard out into the street.

He thanked God that until her dying day, his mother had taken that action for a show of shame and remorse. It was anything but. He’d seen the Tanner’s ice cream sign slowly rotating in the searing hot breeze and had headed straight for the leafy calm of Carnegie, where the people lived who knew how to treat their children. Maybe if he stopped and spoke to a kid up there, they might get friendly and he’d be asked in. He’d often thought of it. That day he decided he would make it a reality. Then she’d see. She’d come home and he’d be in one of those yards drinking Coke with new friends, who had stuff like basketball nets stuck to their walls and blue plastic-walled swimming pools you climbed into from a ladder. There’d be no more kicking around in a dusty yard with nothing to do except scrap with Dean and wait for a worn-out mother to come home and cuss at them.

He ran as far as the sign, then slowed up and turned into the shimmering street with a casual step. The sign had been making a wailing forlorn sound, a kind of whea eee, whea eee like some forest animal’s young looking for its parent. Josh strolled into the splendour of the street and walked slowly, gazing up at the grand houses, smelling the blooms from their gardens. There had been nobody about except for one man who was rooting around in the trunk of a car parked out front.

Josh got ready to say hello as he approached, but on catching sight of him the man straightened up with legs apart, putting his hands on his hips in the manner of a Marine drill sergeant expecting trouble.

He stood like that, staring directly and aggressively at Josh, never taking his eyes from the small boy until he walked by. Josh had felt his cheeks burn.

It was then that he had noticed the sounds. Just background noises at first, but with the blood already beating in his ears, they grew louder and louder until they were roaring in his head.

Lawnmowers buzzing, children shouting and laughing, garden shears snapping, an adult voice calling out, the echoing, plastic sound of a ball bouncing on a hard surface. All these sounds were being made by a ghostly and invisible army of people cruelly hidden from view. And ever present, weaving in and out of these taunting, nightmarish sounds was the whea eee, whea eee of the Tanner ice cream sign. Josh had been paralysed by a sense of desolation that made his bones cold in the thick heat.

The wall of expensive stone that was separating him from these invisible, comfortable, happy people was suddenly grotesque instead of glamorous, an obstacle that could never be negotiated if you were Josh Spiller from Hove Avenue. He had slapped his hands uselessly to his ears, turned and run back the way he had come, fuelling, no doubt, the fears of the man by his car that this was a Hove boy up to no good. Every hot step of the way home the ice cream sign’s wail followed him like a lost spirit, as though it were an alarm he had tripped when he stepped from his world into the forbidden one of his betters.

His mother had welcomed him back with a silent supper of fries and ham, but he could tell by the softness in her eyes she was relieved to see him. Josh knew then how much he loved her. He also knew that no matter how agreeable a house he might eventually buy as an adult, how comfortable an existence he might make for himself, he would always butt up against the corner of a forbidden street, the edge of something better to which he had no access. Maybe that was why he had turned trucker. No one can judge what a man does or doesn’t have if he’s always on the move. The eighteen wheels you lived on were the ultimate democracy. An owner-operator might be up to his neck in debt with his one rig, or it might be one rig out of a fleet of twenty. No one knows if the guy’s rich or poor and no one cares. The questions one trucker asks another are: where you going, where you from, what you hauling, how many cents per mile you get on that load?

No one would ever ask what street you lived on and give you a sidelong glance if it happened to be the wrong one. Josh hadn’t thought about that dumb incident for years, but here, faced with these attractive houses in this small mountain town, he could almost hear the ice cream sign howling forlornly again. It was crazy. He’d grown into a man to whom material possessions meant little or nothing, and yet here he was being infected by that old feeling of desire and denial that he thought he’d shaken off before he’d even grown a pubic hair. And all because a town looked a little neater, a little smugger, a little more affluent than he’d expected. Okay. A lot more affluent.