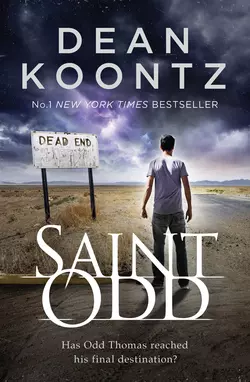

Saint Odd

Dean Koontz

The seventh and final Odd Thomas thriller from the master storyteller.The future is haunting Odd Thomas.The carnival has returned to Pico Mundo, the same one that came to town when Odd was just sixteen. Odd is drawn to an arcade tent where he discovers Gypsy Mummy, the fortune-telling machine that told him that he and Stormy Llewellyn were destined to be together forever.But Stormy is dead and Pico Mundo is under threat once more. History seems to be repeating itself as Odd grapples with a satanic cult intent on bringing destruction to his town. An unseasonal storm is brewing, and as the sky darkens and the sun turns blood-red, it seems that all of nature is complicit in their plans.Meanwhile Odd is having dreams of a drowned Pico Mundo, where the submerged streetlamps eerily light the streets. But there’s no way Pico Mundo could wind up underwater . . . could it?

Copyright (#ulink_3a8162c9-5dd6-5cdb-85db-d60a19c0b9da)

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2015

First published in the USA in 2015 by Bantam Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, A division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Copyright © Dean Koontz 2015

Cover design layout © HarperCollinsPublishers 2015

Cover design by www.mavrodesign.com (http://www.mavrodesign.com)

Cover photographs © Patrik Giardino/Corbis (man, waist up); PhotoAlto/Alamy (man, waist down); Rick Pisio/Alamy (road sign); Sauletas/Alamy (road); Chris Driscoll/Alamy (curb); Mike Olbinski/Getty (sky)

Text design by Virginia Norey

Dean Koontz asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007520152

Ebook Edition © JANUARY 2015 ISBN: 9780007520145

Version: 2015-04-29

Dedication (#ulink_1123ec8f-f908-53c8-831e-ca0c3cd3257a)

This book is dedicated to Frank Redman, who has more than once reminded me of Odd Thomas.

The only wisdom we can hope to acquire

Is the wisdom of humility …

—T. S. ELIOT, East Coker

Contents

Cover (#u3fa37c45-bb87-5012-96f3-716b6a99a2e0)

Title Page (#u12f9cebe-d7a7-5a28-a068-21b751b6133b)

Copyright (#u3d17f466-0d76-5c2e-9c0a-3e3ebb51d818)

Dedication (#u3b10e0ea-abd4-5290-94c1-1002410b1ee5)

Epigraph (#u967ce3ce-41a8-5b54-be29-73918a57155d)

Chapter One (#uc391b1f2-d9e5-5ed0-bfc4-682ac3cec0df)

Chapter Two (#u251d76ee-fcdd-5487-962a-c9eb6f44c989)

Chapter Three (#u0220eabc-2601-5cd3-bf48-0e3fae59aa41)

Chapter Four (#u77f89855-d523-54cd-800e-0e473970e5bc)

Chapter Five (#uf19c98b2-8c8d-5302-8dab-e7894077771e)

Chapter Six (#ua0c72486-a163-5308-971c-30283d8c3324)

Chapter Seven (#u85e519f3-18f4-5266-9393-b9bf1a92c527)

Chapter Eight (#u89019a1b-bf89-5bfe-b811-a886e446db7e)

Chapter Nine (#ub135131e-5930-5f6c-9655-379235d3f45d)

Chapter Ten (#u47bd6ff7-a578-52fd-adaf-85390685b251)

Chapter Eleven (#u89e53c95-3daf-5b2f-ba75-96f4d95a944e)

Chapter Twelve (#u9c0e14c6-5952-553b-97da-5c6a5cbfefde)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-one (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-one (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-one (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-one (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-three (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By Dean Koontz (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

One (#ulink_59291af0-9df0-5a31-bb18-8101153c94e6)

ALONE IN THE VASTNESS OF THE MOJAVE, AT TWO o’clock in the morning, racing along at seventy miles per hour, I felt safe and believed that whatever terror might await me was yet many miles ahead. This would not be the first time in my strange life that safety proved to be an illusion.

I have a tendency to hope always for the best, even when I’m being strangled with a little girl’s jump rope knotted around my neck by an angry, three-hundred-pound Samoan wrestler. In fact, I got out of that difficult situation alive, primarily by getting hold of his beloved porkpie hat, which he considered the source of his good luck. When I spun the hat like a Frisbee and he let go of the jump rope to try to snatch his chapeau from the air, I was able to pick up a croquet mallet and surprise him with a blow to the genitals, which was especially effective because he was wearing only a thong. Always hoping for the best has generally served me well.

Anyway, under a full moon, the desert was as eerie as a landscape on an alien planet. The great black serpent of highway undulated over a series of low rises and gentle downslopes, through sand flats that glowed faintly, as if radioactive, past sudden thrusting formations of rock threaded through in places with quartzite or something else that caught the Big Dog motorcycle’s headlights and flared like veins of fire.

In spite of the big moon and the bike’s three blazing eyes, the Mojave gathered darkness across its breadth. Half-revealed, gnarled shapes of mesquite and scatterings of other spiky plants bristled and seemed to leap forward as I flew past them, as if they were quick and hostile animals.

With its wide-swept fairing and saddlebags, the Big Dog Bulldog Bagger looked like it was made for suburban marrieds, but its fuel-injected, 111-cubic-inch V-twin motor offered all the speed anyone could want. When I had been on the interstate, before I had switched to this less-traveled state highway, a quick twist of the throttle shot me past whatever car or big rig was dawdling in front of me. Now I cruised at seventy, comfortable in the low deep-pocket seat, the rubber-mounted motor keeping the vibration to a minimum.

Although I wore goggles and a Head Trip carbon-fiber helmet that left my ears exposed, the shrieking wind and the Big Dog’s throaty exhaust roar masked the sound of the Cadillac Escalade that, running dark, came up behind me and announced itself with a blast of the horn. The driver switched on the headlights, which flashed in my mirrors, so that I had to glance over my shoulder to see that he was no more than fifty feet behind me. The SUV was a frightening behemoth at that distance, at that speed.

Repeated blasts of the horn suggested the driver might be drunk or high on drugs, and either gripped by road rage or in the mood for a sick little game of chicken. When he tooted shave-and-a-haircut-two-bits, he held the last note too long, and I assured myself that anyone who indulged in such a cliché and then even lacked the timing to pull it off could not be a dangerous adversary.

Earlier, I had learned that the Big Dog’s sweet spot was north of eighty miles an hour and that it was fully rideable at a hundred. I twisted the throttle, and the bike gobbled asphalt, leaving the Caddy behind. For the moment.

This wasn’t the height of bug season in the Mojave, so I didn’t have to eat any moths or hard-shelled beetles when I muttered unpleasantries. At that speed, however, because I sat tall and tense with my head above the low windshield, the warm night air chapped my lips and stung my cheeks as I bulleted into it.

Any responsible dermatologist would have chastised me for speeding barefaced through this arid wasteland. For many reasons, however, there was little chance that I would live to celebrate my twenty-third birthday, so looking prematurely aged two decades hence didn’t worry me.

This time I heard the Escalade coming, shrieking like some malevolent machine out of a Transformers movie, running dark once more. Sooner than I hoped, the driver switched on the headlights, which flared in my mirrors and washed the pavement around me.

Closer than fifty feet.

The SUV was obviously souped. This wasn’t an ordinary mama-takes-baby-to-the-playground Caddy. The engine sounded as if it had come out of General Motors by way of Boeing. If he intended to run me down and paste me to the Caddy’s grille—and evidently he did—I wouldn’t be able to outrace whatever customized engine made him king of the road.

Having tricked up his vehicle with alternate, multi-tonal horns programmed with pieces of familiar tunes, he now taunted me with the high-volume song-title notes of Sonny and Cher’s “The Beat Goes On.”

The Big Dog boasted a six-speed transmission. The extra gear and the right-side drive pulley allowed better balance and greater control than would the average touring bike. The fat 250-millimeter rear tire gave me a sense of stability and the thirty-four-degree neck rake inspired the confidence to stunt a little even though I was approaching triple-digit speeds.

Now he serenaded me with the first seven notes of the Kingsmen’s “Louie Louie.” And then again.

My one advantage might be maneuverability. I slid lower in the seat, so that the arc of the windshield sent the wind over my helmet, and I made more aggressive use of the three-lane highway, executing wide serpentine movements from shoulder to shoulder. I was low to the ground, and the Escalade had a much higher center of gravity than the Big Dog; if the driver tried to stay on my tail, he might roll the SUV.

Supposing he was smart, he should realize that by not mimicking me, by continuing arrow-straight, he could rapidly gain ground as I serpentined. And with easy calculation, he could intersect me as I swooped from side to side of the road.

The third blast of “Louie Louie” assured me that either he wasn’t smart or he was so wasted that he might follow me into a pit of fire before he realized what he had done. Yet another programmed horn blared several notes, but I didn’t recognize the tune, though into my mind came the image of that all-but-forgotten rocker Boy George.

When brakes caterwauled, I glanced back to see the Escalade listing, its tires smoking, as the driver pulled the wheel hard to the right to avoid going off the north side of the pavement. Carving one S after another down the straightaway, I cornered out of the current curve, grateful for the Big Dog’s justly praised Balance Drive, and swooped into the next. With another squeal, the Caddy’s tires laid a skin of hot rubber on the blacktop as the driver pulled hard to the left. The vehicle nearly skidded off the south shoulder of the roadway, listing again but, as previously, righting itself well before it tipped over.

Resorting to his basic horn, the driver made no attempt at a tune this time, but let out blast after blast as if he thought he could sweep me off the bike with sound waves.

Recounting this, I might convey the impression that I remained calm and collected throughout the pursuit, but in fact I feared that, at any moment, I would regret not having worn an adult diaper.

In spite of whatever drugs or beverages had pushed the SUV driver’s CRAZY button and filled him with murderous rage, he retained just enough reason to realize that if he continued to follow my lead, he would roll the SUV. Arrowing down the center of the three lanes, he regained the ground that he’d lost, intending to intersect my bike between connecting curves of my flatland slalom.

The Big Dog Bulldog Bagger wasn’t meant to be a dirt bike. The diet that made it happy consisted of concrete and blacktop, and it wanted to be admired for its sleek aerodynamic lines and custom paint job and abundant chrome, not for its ruggedness and ability to slam through wild landscapes with aplomb.

Nevertheless, I went off-road. They say that necessity is the mother of invention, but it is also the grandmother of desperation. The highway was raised about two feet above the land through which it passed, and I left the shoulder at such speed that the bike was airborne for a moment before returning to the earth with a jolt that briefly lifted my butt off the seat and made my feet dance on the floorboards.

Hereabouts, the desert wasn’t a softscape of sand dunes and dead lakes of powdery silt, which was a good thing, because crossing ground like that, the Big Dog would have wallowed to a halt within a hundred yards. The land was mostly hard-packed by thousands of years of fierce sun and scouring winds, the igneous rocks rich with feldspar, treeless but in some places hospitable to purple sage and mesquite and scraggly plants less easily identified.

Jacked up on oversize tires, more suited to going overland than was my bike, the four-wheel-drive Escalade came off the highway in my wake. I intended to find a break in the land or an overhanging escarpment deep enough to conceal me, or a sudden spine of rock, anything I could use to get out of sight of my lunatic pursuer. After that, I would switch off my headlights, slow down significantly, travel by moonlight, and try as quickly as possible to put one turn in the land after another between me and him. Eventually I might find a place in which to shelter, shut off the bike, listen, and wait.

Suddenly a greater light flooded across the land, and when I looked back, I saw that the Escalade sported a roof rack of powerful spotlights that the driver had just now employed. The desert before me resembled a scene out of an early Steven Spielberg movie: a remote landing strip where excited and glamorous scientists from a secret government agency prepared to welcome a contingent of benign extraterrestrials and their mother ship. Instead of scientists and aliens, however, there was some inbred banjo player from Deliverance chasing me with bad intentions.

In those harsh and far-reaching streams of light, each humble twist of vegetation cast a long, inky shadow. The pale land was revealed as less irregular than I’d hoped, an apparent plain where I was no more likely to find a hiding place than I would a McDonald’s franchise complete with a playground for the tots.

Although my nature was to be optimistic, even cheerful, in the face of threat and gloom, there were times, like this, when I felt as though the entire world was death row and that my most recent meal had been my last one.

I continued north into the wilderness rather than angle back toward the highway, assuring myself that it wasn’t my destiny to die in this place, that I would find refuge ahead. My destiny was to die thirty miles or so from here, in the town of Pico Mundo, not tonight but tomorrow or the day after, or the day after that. Furthermore, I wouldn’t die by Cadillac Escalade; my end would be nothing as easy as that, nothing so quick and clean. Having argued myself into a fragile optimism, I sat up straight in my seat and smiled into the teeth of the warm night air.

As the SUV gained on me, the psycho driver resorted to one of his custom horns again. This time I recognized the title notes of “Karma Chameleon” by Culture Club, which had been fronted by Boy George. The song seemed so apt that I laughed; and my laughter would have buoyed me if it hadn’t sounded just a little insane.

The nitrogen-gas-charged shocks, the rubber-isolated floorboards, and the rubber handgrips all contributed to a smoother off-road ride than I had anticipated, but I expected that I was headed for one kind of mechanical failure or another, or for a collision with an unseen thrust of rock that would dismount me, or a community of rattlesnakes that, flung into the air in the midst of copulation, would rain down upon me, hissing.

I was suffering a brief remission in my characteristic optimism.

Ahead, a long but slight slope led to a narrow band of blackness before the Escalade’s lights revealed a swath of somewhat higher land that shimmered like a mirage. I couldn’t be sure what I was seeing; the sight was no less baffling than an abstract painting composed of geometric forms in pale beige and black, but in case it might be what I needed, I accelerated.

I had to weave among bushy clumps—a colony of pampas grass—that were half dead from too little water, their narrow five-foot recurved blades perhaps sharp enough to cut me, the numerous tall feathery panicles waving like white flags of surrender.

Evidently the nutcase pursuing me did not belong to the Sierra Club, because the Escalade barreled through the pampas grass without hesitation, leaving a path of crushed and shredded vegetation, gaining fast on me.

The ceaselessly repeated signature notes of “Karma Chameleon” and the roar of the SUV’s pumped-up engine were so loud, I knew that it must be close, maybe ten feet behind me. I didn’t dare glance back.

With but three or four seconds to make the right move, I saw that my suspicion about the terrain ahead was correct. I hung a hard right just before the brink.

The Big Dog fishtailed, the rear tire chewing away the lip of the abyss for a moment before it got traction.

Whether the driver’s attention suddenly shifted to the land ahead, whether he remained intently focused on me, in either case the Escalade had too much mass and momentum to come to a stop in time, and it was far less maneuverable than my bike. The wind of its passage swirled dust and dry bits of desert vegetation over me, and the big SUV launched off the rim of the ravine, still blaring “Karma Chameleon” as it briefly took flight.

With its four-piston billet calipers, the Big Dog could stop on a dollar if not a dime. I propped it with the kickstand and swung off and stood at the brink as the spotlight-equipped Caddy, now dropping nose-down like a bomb, illuminated its terminal destination.

Carved by millennia of flash floods and Mojave winds and seismic activity, the crevasse appeared to be about thirty feet wide at the top, less than ten at the bottom, about fifty feet deep. The plunging SUV tested the bedrock at the bottom, and the bedrock won. The last title note of the Culture Club tune came an instant before the crash of impact, the vehicle lights went out, and in the sudden darkness, the SUV shed pieces of itself, which rattled and clattered across the rocks.

I said, “Wow,” which isn’t witty enough for movie dialogue, but it’s what I said. I’m no Tom Cruise.

After a few seconds of darkness, the fire bloomed. It wasn’t an explosion, only low capering flames that quickly danced higher, brighter. The ravine proved to be a trap for tumbleweed that mounded along its bottom, and the spherical masses burst into flame faster to the west of the wreckage, apparently the direction in which gasoline spilled from the ruptured tank.

The walls of the ravine were steep but navigable on foot. The stone shaled away treacherously as I quickly sidled down with all the grace of—I don’t know why this unlikely image occurred to me at the time—a penguin on stilts. Too many years of watching old Warner Bros. cartoons by Chuck Jones can instill in you a silliness gene by proxy.

Perhaps equally silly—I was in my Good Samaritan mode. The driver had tried to kill me, sure, but his homicidal rage might have been the consequence of inebriation, and he might have been a peach of a guy when he was sober. I couldn’t let him bleed or burn to death just because of his idiocy behind the wheel of the SUV. Sometimes I am hampered by having a moral code, but I have it nonetheless, like a burr under the brain, with no way to pluck it out.

Fire flared to both sides of the Escalade, and lesser flames crawled under it, but the interior wasn’t yet ablaze. There were so many tinder-dry tumbleweeds that the ravine would be aglow for quite a while.

As I neared the vehicle, I saw painted on its tailgate neatly formed characters in a pictographic language reminiscent of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics, white against the black paint. I halted and reconsidered the meaning of the encounter with the unknown driver.

A couple of months earlier, on a mountain in Nevada, I had found it necessary to explore a well-guarded estate where, as it turned out, kidnapped children were being held for the purpose of ritual murder by a satanic cult. Before I found the kids, I discovered a stable filled with antique breakfronts instead of horses, and in those breakfronts had stood thick glass jars the size of crocks, filled with a clear preservative, the lids fused in place with an annealing torch. In those jars were souvenirs of previous human sacrifices: severed heads, wide-eyed and open-mouthed, as if in the grip of eternal shock and terror, and on every forehead a different line of a pictographic language exactly like that on the tailgate of the Escalade.

Small-town boy meets big-time evil.

The driver of the Escalade hadn’t encountered me by chance. He had learned what route I was taking, when I would take it, and he’d set out in pursuit of me, no doubt intending to avenge the damage I had done to the cult. I’d killed a number of them. But their resources were impressive—in fact otherworldly—and we were far from finished with each other.

My code of conduct didn’t require me to save the lives of vicious murderers any more than it required me to feed myself to a shark just because the shark happened to be hungry. In fact, I felt obligated to kill murderous sociopaths if that was the only way to prevent them from slaughtering more innocents. Usually, that turned out to be the only way, because few of their kind responded well to reason or to stern warnings, or to the wisdom of the Beatles, which tells us that all we need is love.

The doors of the Escalade had buckled but hadn’t popped open, and if anyone had clambered out of a shattered window, I had not seen him. The driver—and passenger, if there was one—were all but certainly still inside. Maybe dead. At least badly injured. Perhaps unconscious.

As I retreated, the crackling fire under the vehicle abruptly found its way inside, and with a whoosh, the interior filled with flames. I saw no thrashing shadows in the Escalade and heard no screams.

I couldn’t imagine how they had known I was going home to Pico Mundo or when I would make the trip, or what I would be driving. But as I had unusual talents, abilities, and connections, so did they. I might never learn how they had located me. What mattered now was that they were looking for me; and if they had found me once, they could find me again.

They wouldn’t have tried to find me and kill me en route, however, if they had known where I would be staying when I got to Pico Mundo. Instead, they would have waited for me there and cut me down when I arrived. The safe house waiting for me was still safe.

Climbing the shale slope proved more difficult than the descent had been. I kept glancing behind me, half expecting to discover a pursuer, some grotesque nemesis with hair afire and smoke seething from his twisted mouth.

At the top, I looked back and saw that the flames, a bright contagion, had spread maybe sixty yards to the west, from one crisp tumbleweed to another. The shale must have been veined with pyrite, for in the walls of the ravine, in the throbbing firelight, ribbons of yellow glimmered brighter than the surrounding stone. The burning Escalade screaked and twanged. As its metallic protests echoed and re-echoed along the crevasse, they were distorted, changed, until I could almost believe that I was hearing human voices, a suffering multitude crying out below.

I had not seen their faces. I had not killed them, only given them the chance to kill themselves. But still it seemed wrong that I should not know the faces of those I allowed to die.

The noise and the blaze must have disturbed a colony of bats. Just then, no doubt having recently returned to their cave in a ravine wall after a night of feeding, they burst into agitated flight, shrieking as they soared on rising thermals, many hundreds of them, perhaps thousands, their membranous wings snapping in accompaniment to the crackle of the flames. They rose to the top of the ravine, then descended, only to rise again, surged east and then west and then east again, as if confused and seeking something and failing to find it, their shrill cries both angry and despairing.

Life had taught me to believe in omens.

I knew one when I saw it.

The bats were an omen, and whatever they might portend, it would not be an event marked by benevolence, harmony, and joy.

Two (#ulink_4d92f2a5-8acf-5a57-8eeb-6f2cbc79dc29)

I CAME HOME TO DIE AND TO LIVE IN DEATH. MY life had begun in the desert town of Pico Mundo, California, and I had remained there until I was twenty, when I lost what mattered most to me. During the twenty-one months since then, I had traveled in search of my purpose, and I had learned by going where I had to go. That I had come full circle shouldn’t have surprised me, for we are born into time only to be born out of it, after living through the cycles of the seasons, under stars that turn because the world turns, born into ignorance and acquiring knowledge that ultimately reveals to us our enduring ignorance: The circle is the essential pattern of our existence.

The Green Moon Mall stood along Green Moon Road, smack between old-town Pico Mundo and its more modern neighborhoods. The structure was immense because it was intended to serve not just our town but others in the area that were too small to support a mall of their own. With sand-colored walls and curved planes and rounded corners, the architect meant to suggest adobe construction. In recognition of the Mojave heat, there were few windows, and the most glass to be seen was at the several entrances, where pneumatic doors once whisked aside to welcome shoppers.

The mall had been closed for a long time, contaminated by its history of mass murder. Many feared that to reopen it would invite some unhinged person to attempt to rack up a larger kill than the nineteen who were murdered on that day. Of the forty-one wounded, several were disabled for life. Starbucks, Crate & Barrel, Donna Karan, and other retailers had bailed on their leases, having no desire to be associated with a place of such horror. The mall owners, with common sense that was rare in modern America, had taken no tenants to court, instead announcing that the building eventually would be torn down and the land repurposed for upscale apartments.

After parking the Big Dog bike on a nearby residential street, I visited the mall more than an hour before dawn, carrying a pillowcase in which were a bolt cutter, a crowbar, and a sixteen-ounce hammer with a rubberized grip that I’d brought with me from the coast. I found my way by flashlight down a long, wide ramp that led to an immense segmented garage door through which countless eighteen-wheelers had once driven with loads of merchandise for the department stores and the many smaller shops.

The moon was down, the glimmering constellations so distant, and even in May the Mojave night was as mild as baby-bottle milk. On flanking concrete walls that loomed higher as the ramp descended, pale reflections of the flashlight drifted alongside me as if they were spirit companions.

I knew a great deal about the ghosts that haunted this world. I saw those who had died but who, for whatever reasons, would not or could not cross over to whatever came next. My life had been shaped by those lingering dead, by their regrets, their hopes, their needs, their melancholy. In my twenty-two years of life, I had come to regard even angry spirits with equanimity, reserving my dread for certain still-living human beings and the horrors of which they were capable.

To the left of the enormous roll-up door was one of ordinary dimensions, secured with both a mortise lock and a large padlock. I propped my flashlight against the door frame, with its beam angled upward.

Using the long-handled bolt cutter, I severed the shackle from the case of the padlock. I unhooked the padlock from the slotted strap and threw it aside.

The rimless lock cylinder could not be gripped with lever-wrench pliers and pulled out of the escutcheon. From my shirt pocket, I took a wedge-shaped steel tap with a broad head, and I pounded the tap into the keyway of the mortise lock. The poll of the hammer rang off its target, the pin tumblers in the keyway shrieked as the guts of the lock were distorted, and the stricken door clattered in its frame.

I had no concern that the racket I raised would draw unwanted attention. The deserted mall was surrounded by a vastness of empty parking lot, which was these days encircled by chain-link fencing crowned with concertina wire to discourage romantically inclined teenagers in cars, homeless people with their worldly possessions packed in shopping carts, and whatever creeps might be drawn to the place by its history of violence. The police chose not to patrol the property anymore because, after all, everything on it was scheduled for demolition in a few months.

My version of the “Anvil Chorus” was brief. When I’d driven the tap fully into the keyway, the deadbolt rattled loosely in the latch assembly, and a narrow gap opened between door and jamb, although the bolt remained seated in the faceplate. I applied the crowbar and worked up a sweat before I broke into what had been the subterranean loading docks and the employee parking lot beneath Green Moon Mall, leaving my tools behind.

I am a fry cook, at my best when working the griddle, master of the spatula, maker of pancakes so light they seem about to float off your plate. I am a fry cook and wish to be nothing more, but the many threats I face have required me to develop skills not needed in the kitchen of a diner—like breaking and entering.

Stained concrete underfoot, overhead, on all sides, the ceiling supported by columns so thick that I couldn’t have gotten my arms around one: As a deep-sea diver in his pressurized suit and armored helmet might nevertheless sense the tremendous tonnage of the ocean pressing upon him, so I felt the great mass of the two-story mall and the anchoring pair of three-story department stores above me. For a moment, I felt buried, as if I had died on that day of violence and now must be a spirit haunting this elaborate catacomb.

Here and there lay small piles of trash: the splintered boards of a broken packing crate, empty and moldering cardboard boxes, and items not easily identified in the flare of the beam and the dance of shadows.

The rubber soles of my sneakers failed to disturb the absolute silence, as though I had no substance. Then a short-lived rustling sound rose from my left. It must have been a rat disturbed in a nest of trash, but nevertheless I said, “Hello?” The only response was the echo of that word, which in the colonnaded darkness returned to me from all sides.

When last I’d been here, the place had hummed with activity as numerous trucks off-loaded merchandise and harried stockroom clerks prepared it for delivery to the holding rooms and the sales floor, using forklifts and electric carts and hand trucks.

The elevated loading dock ran the full length of the enormous structure. I climbed a set of steel rungs embedded in the face of it, crossed the dock, and pushed through a pair of extra-wide double doors into a spacious corridor with concrete walls painted white. Two freight elevators waited on the left; but even if they were still operative—which I doubted—I didn’t want to be boxed in one of them. I opened a door labeled STAIRS, and I climbed.

From a ground-floor stockroom, I proceeded into what had been a department store. Silence pooled in the cavernous building, and I felt as if something akin to sharks swam through the waterless dark, circling me beyond the reach of the flashlight.

Sometimes entities appear to me that no one else can see, inky and undulant, as quick and sleek as wolves, though without features, terrible and predatory shadows that can enter a room by the narrowest crack between a door and jamb or through a keyhole. I call them bodachs, although only because an English boy, visiting Pico Mundo, once saw them in my company and gave them that name. Seconds later, a runaway truck crushed him to death between its front bumper and a concrete-block wall.

He was the first person I’d ever known with my ability to see the lingering dead and bodachs. Later I discovered that bodachs were mythical beasts of the British Isles; they were said to squirm down chimneys at night to carry off naughty children. The creatures that I saw were too real, and they were interested not solely in naughty children.

They appeared only for horrific events: at an industrial explosion, at a nursing-home collapse during an earthquake, at a mass murder in a shopping mall. They seemed to feed on human suffering and death, as if they were psychic vampires to whom our terror, pain, and grief were far sweeter than blood.

I didn’t know where they came from. I didn’t know where they went when they weren’t around. I had theories, of course, but all of my theories bundled together proved nothing except that I was no Einstein.

Now, in the abandoned department store, if bodachs had been swarming in the farther reaches of that gloomy chamber, I would not have seen them, black forms in blackness. No doubt I was alone, because in that desolate and unpopulated structure, there were no crowds for a gunman to cut down in the quantities that appealed to bodachs. They never deigned to manifest for a single death or even two, or three; their taste was for operatic violence.

Back in the awful day, when I’d come out of the busy department store into the even busier promenade that served the other shops, I had seen hundreds—perhaps thousands—of bodachs gathered along the second-floor balustrade, peering down, excited, twitching and swaying in anticipation of bloodshed.

And I had come to think that they were mocking me, that perhaps they had always known I could see them. Instead of putting an end to me with a runaway truck and a concrete-block wall, maybe they had schemed to manipulate me toward my loss, toward the fathomless grief that would be born from that loss. Such grief might be to them quite delicious, a delicacy.

At the north end of the mall, the ground-floor promenade had once featured a forty-foot-high waterfall that cascaded down man-made rocks and flowed to the south, terminating in a koi pond. From sea to shining sea, the country had built glittering malls that were as much entertainments as they were places to shop, and Pico Mundo prided itself on satisfying Americans’ taste for spectacle even when buying socks. No water flowed anymore.

By flashlight, I walked south along the public concourse. All the signage had long ago been taken down. I could no longer remember what stores had occupied which spaces. Some of the show windows were shattered, drifted glass glittering against the bases on which the large panes had stood. Other sheets of intact glass were filmed with dust.

I had come there with determination, but as I approached the southern end of the building, I moved slower, and then slower still, overcome by cold that had nothing to do with the temperature of the abandoned shopping mall. In memory, I heard the gunfire, the screams, the piercing cries of terror, the slap-slap-slap of running feet on travertine.

At the south end of the concourse lay another vacated department store, but before it, on the left, was the space where once Burke & Bailey’s had done business, the ice-cream shop where Stormy Llewellyn had been the manager.

A tattered hot-pink awning with a scalloped edge overhung the entrance. In memory, I heard the hail of bullets that had shattered the windows and doors, and I saw Simon Varner in a black jumpsuit and black ski mask, sweeping a fully automatic rifle left to right, right to left.

He had been a cop. Secondarily a cop. Primarily an insane cultist. There had been four of them. They murdered one of their own, and I killed one of them. The other two were now in prison for life, where they still worshipped their satanic master.

In that moment of my return, I felt as though I were a spirit, having perished in a forgotten conflict, my body shed and left to decompose in some far field. I was unaware of moving my legs, and I no longer either heard or felt my feet stepping across the dirty travertine. I seemed to float toward the ice-cream shop, as if the white beam before me came not from the flashlight that I held but from some mysterious distant source, levitating and transporting me toward Burke & Bailey’s.

The broken glass had been broomed into small jagged piles. Even under a thin film of dust, the sharp edges of the shards sparkled. I thought, Here lie your hopes and dreams, shattered and swept aside, and could not raise a ghost of the optimism that previously I had been able to conjure even in the bleakest moments.

As I crossed the threshold, I saw in memory Stormy Llewellyn as she had been that day, dressed in her work clothes: pink shoes, white socks, a hot-pink skirt, a matching pink-and-white blouse, and a perky pink cap. She’d sworn that when she had her own ice-cream shop, which she expected to secure by the time she was twenty-four, if not sooner, she would not provide her employees with dorky uniforms. No matter how frivolous the outfit she wore, she was an incomparable beauty with jet-black hair, dark eyes of mysterious depth, a lovely face, and perfect form.

Was. Had been. No more.

I think you look adorable.

Get real, odd one. I look like a goth Gidget.

She’d been standing behind the service counter when Simon Varner opened fire. Perhaps she had looked up as the windows shattered, had seen the ominous masked figure, and thought not of death but of me. She had always considered her own needs less than those of others; and I believe that her last thought in this world wouldn’t have been regret at dying so young but instead concern for me, that I should be left alone in my grief.

Maybe one day when I have my own shop, we can work together …

The ice-cream business doesn’t move me. I love to fry.

I guess it’s true.

What?

Opposites attract.

Until now, I had not returned to Burke & Bailey’s after that dreadful day. I knew that suffering can purify, that it’s a kind of fire that can be worth enduring, but there were degrees of it to which I chose not to subject myself.

The tables and chairs were gone, as well as freezers and milkshake mixers and other equipment. Attached to the back wall was the menu of flavors, topped by Burke & Bailey’s newest offering at that time: COCONUT CHERRY CHOCOLATE CHUNK.

I remembered having referred to it as cherry chocolate coconut chunk, whereupon she had corrected me.

Coconut cherry chocolate chunk. You’ve got to get the proper adjective in front of chunk or you’re screwed.

I didn’t realize the grammar of the ice-cream industry was so rigid.

Describe it your way, and some weasel customers will eat the whole thing and then ask for their money back because there weren’t chunks of coconut in it. And don’t ever call me adorable again.Puppies are adorable.

At the end of the long counter, I opened a low gate and entered the work area from which Stormy had been serving customers when the shooting started. The flashlight revealed vinyl tiles littered with plastic spoons, pink-and-white plastic straws, and dust balls that quivered away from me as I moved.

I relied on intuition to stop at the very place that Stormy had been standing when she’d been cut down. The stains underfoot were more than a year and a half old, and I considered them only briefly before moving past them and sitting on the floor.

This was the still point around which my life turned, the axis of my world. Here she had died.

I switched off the flashlight and sat in darkness so complete that it seemed as if all the light had gone out of the world and would never return.

After her death, her spirit had lingered for some days this side of the veil. My grief was so heavy, so bitter, that I couldn’t endure it, and for a while I lived in denial. Lingering spirits look as real to me as do living people. They are not translucent. Neither do they glow with supernatural energy. If I touch them, they have substance. They do not talk, however, and Stormy’s silence should have at once told me that her spirit had left her body and that before me stood the essence of the girl I loved, her splendid soul, but not the girl complete and physical. My denial was close to madness; I imagined conversations between us, made meals that she could not eat, poured wine she could not drink, planned a wedding that could never be consummated. By my desperate longing, I held her to this world days after she should have passed on to the next.

Now, sitting on the floor, behind the counter in the ice-cream shop, I spoke to her, unconcerned that with my paranormal talent I might draw her back into this troubled world. Those who pass to the next life do not return. Not even the power of love, as intense a love as any a man had ever felt for a woman, could open a door in the barrier between Stormy and me.

“It won’t be long now,” I said softly.

I felt that she could hear my words even a world away. That may sound weird to you, but stranger things have happened to me. When you have come face-to-face with a senoculus, a six-eyed demon with human form and the head of a bull, you grow more open-minded about what might and might not be possible.

Besides, I have no choice but to believe that all our lives are woven through with grace, because only then could the promise made to me and Stormy come true.

Six years earlier, when we were sixteen, we went to Pico Mundo’s annual county fair. At the back of a carnival-arcade tent stood a fortune-telling machine. We dropped a quarter in the slot and asked if we would have a long and happy marriage. The card given to us couldn’t have been more reassuring: YOU ARE DESTINED TO BE TOGETHER FOREVER.

Framed behind glass, that card had hung above Stormy’s bed when she still lived. I carried it now in my wallet.

I whispered again, “It won’t be long now.”

I don’t believe it’s possible to imagine a favorite scent, to recall a fragrance as vividly as one can hear a tune in the mind’s ear or see in the mind’s eye a place visited long ago. Nevertheless, as I sat there in the lightless shop, I smelled the peach-scented shampoo that Stormy had used. After a shift cooking in the Pico Mundo Grille, when my hair had sometimes smelled like hamburger grease and fried onions, she gave me that same shampoo; but I hadn’t been able to find the brand anymore and hadn’t used it in months.

“They’re coming to Pico Mundo. More cultists. Inspired by those who … murdered you. They aren’t content anymore with quiet rituals and human sacrifices on secret altars. What happened here has shown them a more thrilling way to … practice their faith. In fact, I think they’re already in town.”

No sooner had those words escaped me than I heard laughter in the distance and then voices echoing through the mall.

I started to get to my feet, but a blush of light rose across the face of the darkness, and I stayed below the counter.

Three (#ulink_ab985d03-d790-5062-89ab-1f37050421e0)

THE VOICES ABRUPTLY GREW LOUDER WHEN THE new arrivals entered the former ice-cream shop. Unless others were present who did not speak, there were three of them, a woman and two men.

Fearing that they might lean over the counter or come to the end of it to shine their flashlights along the service area, I eased into a space once occupied by an under-the-counter refrigerator or other piece of equipment, into cobwebs that clung like a veil to my face and tickled my nostrils toward a sneeze.

As I wiped the veil away and imagined poisonous spiders, the woman asked, “What was the body count, Wolfgang? I mean in this store alone?”

Wolfgang had a voice perhaps roughened by countless packs of cigarettes and more than a little whiskey taken neat and therefore scalding. “Four, including a pregnant woman.”

I had thought they must have found the door through which I’d forced entry, the tools that I’d left behind. But they didn’t seem to be searching for anyone; evidently they had entered the mall by a route different from mine.

The second man had a soft voice, naturally mellifluous but too honeyed, as though he must be so practiced in deceit that even when he was in the company of his closest comrades and speaking from the heart, he could not change his tone to match the circumstances. “Mother and child taken together. Such admirable efficiency. Two for the price of just one bullet.”

“When I said four,” Wolfgang replied with a note of impatient correction, “I wasn’t, of course, counting the unborn.”

“Incunabula,” the woman said, which meant nothing to me. “It wasn’t in the newspaper count of nineteen. Why would you think it had been, Jonathan?”

Rather than reply, the corrected efficiency expert, Jonathan, changed the subject. “Who were the other three?”

Wolfgang said, “There was a young father and his daughter …”

I had known them. Rob Norwich was a high-school English teacher who sometimes had Saturday breakfast with his daughter, Emily, at the Pico Mundo Grille. He loved my hash browns. His wife had died of cancer when Emily was only four.

“How old was the child?” the woman asked.

“Six,” Wolfgang replied, adding a sort of sigh to the end of the word, making two syllables of it.

I wondered who these people were, for what purpose they had found their way into the mall. Perhaps they were merely three more of those legions whose patronage made hits of torture-porn horror movies, on vacation and eager to satisfy their morbid curiosity by touring mass-murder sites. Or maybe they were not as innocent as that.

“Just six,” the woman said, as if relishing the number. “Varner would’ve been well rewarded for that one.”

Simon Varner, the bad cop, the gunman on that day.

Wolfgang had all the facts. “Her father’s face was blown away.”

Jonathan said, “Any chance the coroner determined which of those two was shot first, Daddy’s girl or Daddy himself?”

“The father. They say the daughter held on for about half an hour.”

“So she saw him shot in the face,” the woman said, and seemed to take smug satisfaction in that depressing fact.

One of the flashlight beams traveled up the long list of ice-cream flavors on the back wall, which I could still see from the nook in which I hid, and at the top it came to rest for a moment on COCONUT CHERRY CHOCOLATE CHUNK.

“Victim four,” said Wolfgang, “was Bronwen Llewellyn. Twenty years old. The store manager.”

My lost girl. She disliked the name Bronwen. Everyone called her Stormy.

Wolfgang said, “She was a good-looking bitch. They showed her photo on TV more than any of the others because she was hot.”

The beam traveled across the flavor list, to the wall and down, lingering for a moment on a pattern of blood spray that once had been scarlet but was now the color of rust.

“Is this Bronwen Llewellyn important?” asked Jonathan. “Is she why we’ve come here?”

“She’s one reason.” The light moved away from the bloodstains. “Ideally, she’d be buried somewhere, we could dig her up, use the corpse to mess with his mind. But she was cremated and never buried.”

In addition to seeing the spirits of the dead, I have a gift that Stormy called psychic magnetism. If I drive around or bicycle, or walk, all the while thinking about someone—a name, a face—I will sooner than later be drawn to them. Or they to me. I didn’t know these three people, wasn’t thinking about them before they arrived; nevertheless, here they were. This might have been unconscious psychic magnetism—or mere chance.

“Who has her ashes?” the woman asked.

“I don’t know. Several possibilities.”

Their footsteps retreated from the ice-cream shop, and distance dimmed the lights they carried.

I came out of hiding, rose to my feet, and hurried to the gate at the end of the counter. Regardless of the risks, I needed to know more about those people.

Four (#ulink_be93f8d7-39ef-5302-acd6-831e56763ab6)

REVEALED ONLY AS SHADOWY FORMS WIELDING swords of light, the trio moved leisurely toward the north end of the mall, pausing to fence with the darkness and illuminate one point of interest or another.

I dared not switch on my flashlight. Their conversation gave me some cover, but if I followed blindly in their wake, I was likely to step on something that would make enough noise to attract their attention.

My dilemma was resolved when a hand laid on my shoulder made me turn my head, whereupon I came face-to-face with a softly glowing man who had no face. Eyeless sockets regarded me from a mask of bullet-torn flesh and shattered bone.

After so many years of supernatural experience, I was by then immune to the sudden fear that others would have experienced at the unexpected touch of a hand in the dark. Likewise, the hideous face—or the absence of one—inspired no fright, but instead sadness and pity.

I could assume only that here stood the spirit of Rob Norwich, who had died in the ice-cream shop almost two years earlier, the father of six-year-old Emily, who had also died. If the child had moved on from this world, her father had not.

Never before had a spirit appeared radiant to me, and I thought he manifested in this manner so that, by accompanying me, he might serve as a lamp to reveal the way. Aglow or not, he could be seen only by me, and the light that he emitted, although it revealed the floor around us, most likely also remained invisible to Wolfgang and Jonathan, and to the nameless woman.

His face in death resolved into the countenance he possessed when alive, the wounds closing up. Rob had been thirty-two, with receding blond hair, pleasant features, and eyes the soft green of cactus skin.

He cocked his head as if to inquire whether I understood his purpose, and I nodded to confirm that I did and that I trusted him. The dead don’t talk. I don’t know why.

Quickly he led me to the nearby escalator, which was powerless now, only a staircase of grooved steel treads that angled over the dry formation that had once been the koi pond. I followed him up to the second floor, for the moment heading away from the creepy trio that interested me.

I feared that the escalator, so long out of service, would creak or clatter underfoot. The treads were firm, however, and they weren’t littered with debris.

At the top, I followed Rob Norwich to the right and then north, keeping away from the storefronts, staying near the railing beyond which, had there been more light, I could have looked down into the ground-level promenade. Here and there lay scatterings of trash, but guided by the spirit’s radiance, I was able to step over or around the debris without making a sound.

On the lower promenade, the suspicious trio halted, flashlights concentrated on something beneath the upper concourse on which I stood. Bullet-pocked walls, perhaps. Or an interesting pattern in a spray of blood.

Hoping that their faces might be at least half revealed in the backwash of light, I leaned against the railing and peered down at the group. But the angle was too severe for me to see much about them.

I don’t know what gave me away. I’m sure that I didn’t make a sound. Perhaps I disturbed some small piece of litter that rolled between the balusters and fell past one of the men below, because abruptly he turned his flashlight toward me. The bright beam found my face and dazzled me so that I couldn’t clearly see him or any of them.

Rob Norwich, my most recent friend among the dead, put a hand on my shoulder again, and I turned to him as, in the concourse below, Wolfgang shouted, “That’s him. Get him. Kill him!”

Any remaining illusion I had that these people might be mere horror junkies, touring the mall because of its bloody history, evaporated. Although they hadn’t known that I was there, they had come because they were associated with the demonic cult that I had infiltrated in Nevada, and this place inspired them. They were in Pico Mundo to honor the mass murderers who had shot up Green Moon Mall back in the day, to honor them by committing some greater atrocity elsewhere in town.

Because of the events in Nevada, they knew that I might be the only one who could foil them. This chance encounter—if anything in life occurred by chance—gave them an opportunity to waste me, thereby improving the odds that their specific intentions wouldn’t be known until it was too late for anyone to stop them.

My ghostly companion, who served also as my guiding light, hurried toward the nearer of the two abandoned department stores that anchored the shopping mall, the one at the south end. He must have had an exit strategy in mind for me, but I didn’t follow him.

Rob had been a good man in life, and I didn’t worry that his spirit might be malevolent. He was not intent on leading me into the arms of my enemies.

The lingering dead, however, aren’t entirely reliable. After all, for whatever reasons, in spite of the certainty that they can’t undo their deaths and that there is no satisfying future in the haunting business, they’re either reluctant to leave the beauty and wonder of this world or afraid of stepping into the next one. They are not acting rationally regarding the most important issue before them; therefore, trusting in them without reservation was even less likely to work out well for me than trusting an IRS auditor to help me find beaucoup tax deductions that I might have overlooked.

Now that Wolfgang and his two comrades knew where I was, they would most likely head to the south escalator, by far the nearest route to the second-floor promenade. I was unlikely to make it into that empty department store before they could cut me off.

Instead, daring to hurry through the darkness, I went north and made considerable distance before stumbling over something and knocking it aside, whereupon I heard the woman shout, “He’s going that way!”

I no longer had a reason to risk the darkness. I switched on my flashlight, cupping one hand around the lens to make it less visible from below.

As I reached the end of the promenade, I heard booming footsteps and rattling metal: someone running up the north escalator, which evidently wasn’t in as good condition as the one at the south end that I had climbed so quietly. Suddenly a light speared upward, searching for me, as the person on those stairs reached the halfway point.

The doors to the northern department store, pneumatic sliders, no longer operative, were frozen in the open position. I raced through them, into what had once been a temple to luxury goods, where the god of excess consumption held court. Many of the display cases had been left in place, and I ducked behind them, hunched and hustling, until I heard my hunters shouting to one another, and then I halted and switched off the flashlight.

Now what?

Five (#ulink_149cfe03-e800-5dc2-ad50-fbe5790bc09c)

MY PSYCHIC MAGNETISM WORKED BEST WHEN I was seeking someone whose face and name I knew, though one or the other would usually suffice. On a few occasions, I had conjured in my mind the image of an object for which I was searching, and eventually I was drawn to it, though not in as timely a fashion as when my quarry was a person.

As the three hunters spread out in the department store, I pictured the pillowcase that contained a bolt cutter, a crowbar, and a hammer. I had left it just inside the door through which I’d broken into the mall.

When I felt the urge to move, I set out once more, hunched and scuttling as silently as possible. I followed the display cases, all with glass fronts and tops but with solid backs that would shield me from the cultists—unless one of them stepped into the aisle along which I traveled. At an intersection with other rows of cabinets, I turned right, moving steadily away from what little illumination the distant flashlight beams provided when they ricocheted off the walls and columns and glass displays.

Forward into darkness.

I had never before counted on psychic magnetism to make my way through pitch-black rooms, but only to lead me eventually to that which I sought. Now I decided that having paranormal abilities wouldn’t mean much if, on the way to my goal, my wild talent could run me head-on into a wall, send me tumbling down a staircase, or drop me into an open shaft. Surely I could trust it now, had to trust it, just like Spider-Man trusted his web-spinning ability to swing from skyscraper to skyscraper even though the briefest interruption in his production of spider silk could drop him eighty stories to the street below.

Of course, Spider-Man was a comic-book character. He couldn’t die unless the company that owned him was in the mood to flush away a multibillion-dollar property. I was a real person, and I wasn’t worth multiple billions to anyone.

I ventured into lightless realms, although tentatively at first, sliding one hand along a display case. My other hand was extended in front of me, alternately anticipating a wall where empty air should be and feeling the floor to avoid a sudden drop-off or debris.

At the rate I was going, I wouldn’t escape the three searchers, and even if I did elude them, I’d die of thirst or starvation before I got to the pillowcase of tools that I pictured in my mind’s eye.

I had always assumed that my gift was just that, a gift, not the result of a rare gene or of some beneficial brain damage related to my mother’s consumption of martinis during her pregnancy. A gift like mine seemed to come from some higher power, and whatever the source—whether God or space aliens or wizards living in a parallel Earth where magic worked—it must be a benign higher power, because I was motivated to help the innocent and afflict the guilty. I had no desire to use my abilities to amass colossal wealth or to rule the planet with either a velvet glove or an iron fist.

Taking a deep breath, all but totally blind, trusting in my psychic magnetism as Spidey trusted in his web spinning, as Wile E. Coyote trusted in products sold by Acme to snare or kill the Road Runner, I rose somewhat and, in the hunched posture of an ape, hurried forward. If trash of any kind littered the floor, I didn’t once set foot on it. If there were obstacles in my way, I didn’t collide with them. Intuitively, I turned this way, that way, this way, marveling at my ability to navigate successfully and with hardly a sound.

I had always been in awe of Stevie Wonder and Ray Charles, blind men who sat at their pianos and never played a bad note, absolutely certain of where the keys were in relation to their fingers. I dared to feel a connection with them, though I had no more musical talent than a rock; standing taller, moving rapidly and successfully through total darkness, I thrilled to the experience as sometimes I had thrilled to Stevie’s and Ray’s piano work.

The searchers fell far behind me. I couldn’t see even the most indirect glow of their lights. I couldn’t hear them, either, though perhaps because my heart was pounding so hard that the blood-rush roar in my ears was like my own private Niagara.

With my right shoulder, I brushed against something, only the slightest contact, but it alarmed me, and I stopped. I turned, felt around me as if in a game of blind man’s bluff. I discovered a doorless doorway, the cold metal jamb slightly oily to the touch.

I thought I knew where I was. This must be the stockroom that had once supplied the sporting-goods department, from which stairs led down to the employees-only level under the mall. On the day of the mass murder, when I’d passed through this place in the grip of psychic magnetism, desperately seeking the gunman, Simon Varner, before he could kill, I had encountered a pretty redhead busily pulling small boxes off packed storage shelves. She’d said Hey, in a friendly way, and I’d said Hey, and I had kept moving through the door and onto the sales floor, expecting the dreadful sound of gunfire at any moment—which had come only a few minutes later.

Now I heard a voice. A woman. But not the redhead. One of the searchers. She was shouting, excited. I was too far away to hear exactly what she said, but I caught the word footprints.

The mall had been abandoned for many months. Time might have laid a thin carpet of dust, probably not everywhere but here and there, revealing part of the route I had taken.

Suddenly, out there beyond the stockroom, a flashlight flared, another, a third. They were closer than I expected.

Picturing the pillowcase full of tools once more, I hurried across the stockroom, stopped, felt a door jamb where I expected it, and stepped blindly onto the first step of the two flights of stairs that led down to the mall’s underworld. Using the railing to steady myself, I descended as far as the mid-floor landing before I heard voices above, perhaps not in the stockroom yet but approaching it.

I hustled down the last flight, eased open the fire door just far enough to slip through, closed it as quietly as possible, and switched on my flashlight. Here in the wide service corridor, dust hadn’t settled as it had in the high-ceilinged, cavernous sales floor above. I’d left no footprints on my way in; and I would leave none on my way out.

From the stairwell behind me came an eager voice, footsteps descending.

If I followed the route by which I had originally entered the mall, there was nowhere close to hide. The two freight elevators featured open-work steel gates instead of solid sliders. Farther away were the double doors to the loading dock, which I couldn’t possibly reach before the cultists arrived and saw me.

I turned in the opposite direction, where there were rooms on the left side of the corridor. I hurried to the nearest door, opened it, switched off my flashlight, and crossed the threshold as I heard my pursuers spilling out of the stairwell.

As I quietly shut the door, a stench rose around me, the stink of rot and feces and sulfur and—strangely—ammonia so intense that I gagged and my eyes watered. I dared not step farther into whatever living nightmare might await me, but I couldn’t flee to the corridor, either. I eased to my left and pressed my back to the wall.

The hinges immediately to my right made a grinding bone-on-bone sound as the door opened. The nameless woman rattled off a series of colorful words to express her disgust at the malodor and at the sight that her flashlight revealed.

Approximately forty feet on a side, the room offered foot-deep mounds of whitish matter streaked with gray and mottled with yellow, nearly all of it heaped toward the back half of the space. The stuff glistened in many places, lay dry and cracked and pocked in others, and busy beetles scurried across it, like miniature mechanical moon rovers exploring the surface of an airless world. Here and there, bristling from the hideous mass were dark, twisted, spiky things that, after a moment, I realized must be dead bats that were especially interesting to the beetles.

The woman’s flashlight beam traveled up to a wall-to-wall grid of metal rods suspended a foot below the true ceiling, from which perhaps merchandise had once been hung while it awaited delivery to stores overhead. The filth-encrusted rods were less interesting than the bats depending from them. The flourishing colony hung for the most part in sleep, but the traveling light encouraged a few to open eyes that glowed like yellow-orange jewels.

Wolfgang, the guy with the whiskied voice, cursed and said, “Close the damn door, Selene.”

Fortunately, Selene didn’t slam it. She eased the door shut as though she had accidentally lifted the lid of Dracula’s coffin and, being without garlic or a pointed stake, hoped to slip away before the thirsty count bestirred himself.

I heard the trio talking in the corridor, but I couldn’t make out what they were saying.

Inhaling the disgusting odor of dung and rot and musk, I stood with my back to the wall and waited for one of the bats to squeak. One of them did. Then another.

Six (#ulink_3b7f314c-0c2f-5d74-a674-7cc1b660a8dd)

AMARANTH.

Between the rescue of the kidnapped children in Nevada and my return to Pico Mundo, I lived for two months in a cozy three-bedroom seaside cottage with Annamaria. It was in this charming house, in late May, on the night before I would ride the Big Dog motorcycle across the Mojave, that I had the dream of the amaranth.

Having met in late January, on a pier in the town of Magic Beach, farther up the coast from where we lived now, Annamaria and I were friends, never paramours. But we were more than friends, because she was, like me, more than she appeared to be.

During the four months that I had known her, she’d been eight months pregnant. She claimed that she had been pregnant not merely eight months but a long time, and she said that she would be pregnant longer still. She never spoke of the father, and she seemed to live without worry about her future.

Many things she said made no sense to me, but I trusted her. She wrapped herself in mystery and had some purpose that I could not comprehend. But she never lied, never betrayed, and compassion shone forth from her as light from the sun.

Neither a great beauty nor plain, she had flawless skin, large dark eyes, and long dark hair. She never wore other than sneakers, elastic-waist khakis, and baggy sweaters. Because she was petite in spite of her swollen belly, she always looked like a waif, though she claimed to be eighteen.

She sometimes called me “young man.” I was four years older than Annamaria, but this habit of hers also seemed right.

I knew her only hours when she told me that she had enemies who would kill her and her unborn child if they got the chance. She had asked if I would die for her, and I had surprised myself by sayingatonce, “Yes.”

Although she pretended that I served as her valiant protector, she did more to pull me out of one dangerous place or another than I ever did for her.

On the night that I dreamed of the amaranth, Annamaria and I and the nine-year-old boy named Tim slept in our separate rooms in the cottage. A golden retriever, Raphael, shared the child’s bed. Rescued three months earlier from horrific circumstances, Tim now had no family but us. I’ve written of him in the seventh volume of these memoirs and won’t repeat myself in this eighth.

In Greek mythology, the amaranth was an undying flower that remained at the peak of its beauty for eternity. But the dream did not begin with the flower.

From a peaceful sleep, I plunged into a nightmare of chaos and cacophony. Screaming rose all around me. Some of the voices were fraught with terror, but an equal number seemed to shriek with a glee that was more disturbing than the fearful cries. Wound among all the human voices was another tapestry of grotesque sound, churr and howl and ululation, bray and squeal and clangor. Much light in many colors whirled and throbbed, yet did not illuminate. Racing streams of red and yellow and blue smeared across my eyes and blurred my vision. I could not understand what little I was able to see: a giant stone wheel, three or four stories high, rolling, rolling straight toward me at tremendous velocity; faces swelling like balloons about to burst, but then shrinking as they deflated; hundreds of hands simultaneously grasping at me and thrusting me away …

Seven (#ulink_6efe00f8-379d-5628-8d8b-3399aa2634a9)

THE DESERTS OF CALIFORNIA AND THE SOUTHWEST provide a sustaining environment for a variety of bats. Earlier, I hadn’t been surprised to see them swarming out of a cave mouth at the bottom of the ravine into which the Cadillac Escalade plunged, but I had not the slightest expectation of finding them in a shopping mall basement, not even if the mall was long abandoned and awaiting a wrecking crew. There must have been an exit from this room by which they left to hunt after nightfall and by which they returned each day before dawn, perhaps a ventilation shaft, maybe a chaseway for plumbing or electrical cables.

I had thought the first flight of bats must be an omen, and after this more intimate encounter such a short time later, I had no doubt that the bats augured something. The problem with omens is that they never come with an illustrated pamphlet explaining what they mean. I am no better at interpreting them than I would be at puzzling out the meaning of a conversation between a guy speaking Uzbek and a guy speaking Eskimo, which I tried to do once when a multilingual Eskimo and a multilingual Uzbekistani were arguing about which one had the best reason to kill me.

At that moment, just after Selene had shut the door, closing me in with the stench, I was less concerned about the meaning of signs and portents than about holding down my gorge, which seemed on the verge of leaving my stomach and erupting in a credible imitation of Mount Vesuvius.

I stood listening to voices in the corridor and to the squeaks and the ruffling of wings as the bats settled down after the brief annoyance of the opened door and the intrusion of the flashlight. I gagged, and the residents of the room didn’t seem to appreciate the sound I made, perhaps taking it as criticism, and so I resolved not to gag again, as I was always loath to give offense.

Trapped between the cultists and the winged horde, I tried to remember everything that I knew about bats. My friend Ozzie Boone, the four-hundred-pound bestselling mystery novelist who mentored my own writing, had written a novel that involved murder-by-bats as a red herring. When Ozzie became fascinated with a new line of research, he insisted on sharing his enthusiasm, no matter how creepy the subject might be, though vampire bats weren’t as disturbing as what he shared when he wrote a story in which the victim was murdered by a personal chef who fed him watercress salads infested with the tiny eggs of liver flukes.

Bats were the only mammals that could fly. Flying lemurs and flying squirrels, swooping from one treetop to another, were only gliding; they didn’t possess wings to flap. Bats did not get tangled in people’s hair. They were not blind. Even in absolute darkness, a bat could find its way by echolocation; therefore, I suppose that, considering my psychic magnetism, I should have felt some kinship with these creatures. I did not. I never had quite gotten a handle on that multicultural thing. Most of the species in the Mojave were insect eaters, though a few fed on cactus flowers and sage blossoms and the like. There were vampire bats, too.

The vampires were small, maybe four inches. The size of a mouse. They weighed little more than an ounce. Each night, they could eat their own weight in blood. A vampire bat would never kill me, but a thousand might be seriously draining.

Maybe these were vampire bats. Maybe they weren’t.

Of course they were. Other than griddle work, nothing ever came easy to me.

In the pitch-black room, the disturbed colony had grown quieter, most of the restless insomniacs at last joining their blood-crazed companions in slumber, lost in dreams that I would definitely not try to imagine. A soft brief rustle here. A thin squeak over there. The harmless little noises of the last few weary individuals getting cozy for their morning sleep.

Death by vampire bats would be less painful than you might suppose. Their teeth were so exquisitely sharp that you wouldn’t even feel the cuts they made. People were rarely bitten by vampire bats, which mostly drank the blood of chickens, cattle, horses, and deer.

I didn’t find the word rarely as comforting as the word never.

In the corridor beyond the closed door, the voices of the three cultists had faded completely away. Their silence didn’t mean that they had given up their search for me and had gone back to their usual activities, like strangling babies and torturing kittens. No offense intended to the satanists who might be reading this, but I have found that those who worship the devil tend to be sneaky, more deceitful by far than your average Methodist—and proud of it. They might still be in the mall basement or garage, standing silently in the darkness, waiting for me to show myself, whereupon my life would be worth spit, and in fact less than spit.

Some people believe that a vampire bat is attracted by the smell of blood, that you have to be bleeding, even if from a tiny puncture or a scratch, before the little beasts will be drawn to you in a feeding frenzy. That is not true. Instinctively, bats know that any creature that sweats also bleeds. If a molecule or two of sweat, floating on the air, found its way into the folds of their nostrils, they would twitch their whiskers and bare their razor-edged teeth and lick their thin lips and, in the current situation, be pleased by the realization that someone had ordered takeout and it had been delivered.

I was perspiring.

Something crawled off my shirt and onto my throat and explored the contours of my Adam’s apple. Over the years, after numerous shocks and horrific encounters, my nerves had become as steady as solid-state circuitry. I figured one of the beetles that had been eating the dead bats in the dung pile had found its way up my body, too light to have been felt through my clothes. Instead of shrieking like Little Miss Muffet, I reached up to my throat and captured the insect in my fist.

Because of the ick factor, I didn’t want to crush the bug. But when I attempted to throw it back toward the dung pile from which it had come, the vicious little thing stuck to my hand with the tenacity of a tick.

Ozzie Boone had written a novel in which the villain threw one of his victims, an IRS agent, into a pit seething with carnivorous beetles. In spite of the tax man’s flailing, stomping, and desperate attempts to climb out of that hellhole, the voracious swarm killed him in six minutes and stripped his bones of every last scrap of flesh in three hours and ten minutes, not as rapidly as piranhas might have done the job, but impressive nonetheless.

Sometimes I wished that my mentor had been Danielle Steel.

I opened my right hand, in which the beetle had gotten a death grip on my palm, made a catapult of the forefinger and thumb of my left hand, and flung the noxious little bugger back into the reeking darkness.

I hadn’t heard a sound from the three cultists in a few minutes, and as I listened intently to the occasional bat rearrange its wings around itself as though adjusting its blanket, I wondered if the castaway beetle had been an outlier, more adventurous than others of its kind. Or even now were numerous others exploring my shoes and climbing the legs of my jeans?

If I have machinelike steady-state nerves, I unfortunately also have the imagination of an acutely sensitive, hyperactive four-year-old on a sugar high, a four-year-old with an understanding of death equal to that of a war veteran.

Although I felt certain I would die here in Pico Mundo within days, I told myself that the fatal moment had not yet arrived, and that it was not my fate to be beetled to death. I would have been reassured if I hadn’t lied to myself often in the past.

I was about to bolt from beetles real and imagined, from bats sleeping or not, when I heard a door slam in some far region of the basement, and I concluded that the cultists must still be searching for me.

I had not seen their faces. Although I knew their first names, they were anonymous. A strange thought disturbed me: If they should kill me, and if we met eventually in some place beyond the grave, they would know me, but I would not know them.

Given more time to recall what I had learned about bats from Ozzie Boone, I remembered that a minimum thirty percent of any colony would reliably be infected with rabies.