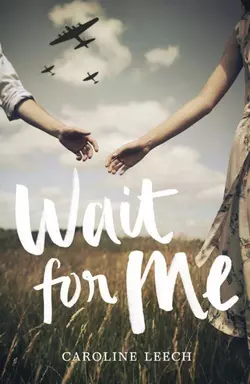

Wait for Me

Caroline Leech

Can their love survive a war?A breathtaking WW2 romance for fans of CODE NAME VERITY and BETWEEN SHADES OF GREY.It’s 1945, and Lorna Anderson’s life on her father’s farm in Scotland consists of endless chores, rationing and praying for an Allied victory. So when Paul Vogel, a German prisoner of war, is assigned as the new farmhand, Lorna is appalled. How can she possibly work alongside the enemy when her own brothers are risking their lives for the country?But as Lorna reluctantly spends time with Paul, the more she sees the boy behind the soldier. Soon Lorna is battling her own warring heart. Loving Paul could mean losing her family and the life she’s always known. But with tensions rising all around them, Lorna must decide how much she’s willing to sacrifice – before the end of the war determines their fate once and for all.

First published in the USA by HarperTeen, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers, in 2017

Published simultaneously in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2017

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins website address is:

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Text copyright © Caroline Leech 2017

The quotation on here (#litres_trial_promo) is reprinted courtesy of The Scotsman.

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2017

Cover images: Battle of Britain aeroplanes © Getty Images; figures, sky and field © Trevillion Images

Caroline Leech asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of the work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008213398

Ebook Edition © 2017 ISBN: 9780008220280

Version: 2016-12-12

“A delicately written love story with a gorgeously evoked setting, an intrepid heroine, and a knee-weakening romance. Not to be missed.”

—ANNE BLANKMAN, author of the Prisoner of Night and Fog series and Traitor Angels

“A sweetly engaging and richly authentic historical romance. Wait for Me charms and satisfies.”

—JOY PREBLE, author of the bestselling Dreaming Anastasia series

“Compelling, moving, and beautifully written, this extraordinary debut novel is rich with history, conflict, and tension.”

—SARAH ALEXANDER, author of The Art of Not Breathing

To my mum and dad,

Shirley and Jimmie Sibbald

Till a’ the seas gang dry, my dear,

And the rocks melt wi’ the sun;

And I will luve thee still, my dear,

While the sands o’ life shall run.

from A Red, Red Rose

ROBERT BURNS, 1759–1796

Contents

Cover (#u3625c4b9-86ac-50d5-a986-7dcd9e6b4ae2)

Title Page (#u20d55ddd-b71c-5201-b7ce-694fa797e384)

Copyright (#u8aaa4b5c-a0a3-593f-b68b-e3e3aac67561)

Praise for WAIT FOR ME (#u8cb90ac4-1e96-56a1-9731-608fad4221a3)

Dedication (#u7c6f12b0-f24c-5f11-9ad7-1cf901206d1a)

Epigraph (#u2a81f062-4358-562b-8553-40fb1113e7a0)

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

About the Publisher

One (#u69f1a894-96a0-5325-941d-ea07400e07b2)

CRAIGIELAW FARM, ABERLADY,

EAST LOTHIAN, SCOTLAND

FEBRUARY 8, 1945

Lorna Anderson was ankle deep in muck and milk. And she was late. Again.

She really didn’t have time to clean up yet another of Nellie’s messes and still make it to school before the bell. Of course, this wasn’t the first time that Lorna had somewhere important to be, yet here she was, broom in hand.

And to make Lorna’s morning complete, her dad was raging at Nellie.

“What in the devil’s name did you think you were doing, you glaikit girl? Can you not even carry a bucket without dropping the damn thing?”

“But Mr. Anderson—” began Nellie.

Lorna kept her head down and the yard broom moving. She tried to push the dogs away from the reeking, steaming mess, but Canny and Caddy dodged around her. They were determined to lick the spilled milk from every crevice in the farmyard’s cobblestones, savoring this rare treat, and apparently oblivious to the shouting above their heads.

“If you’d been concentrating on the matter in hand, lassie,” her dad continued, “you wouldn’t have all these accidents. Particularly when the matter in your hand is a big bucket of my cows’ milk.”

The farmer’s bulk cast a threatening shadow over Nellie, so petite even in her thick and unflattering Land Girl uniform, but Lorna wasn’t too worried. Nellie was made of stronger stuff.

Right on cue, Nellie trilled cheerily, “Oh, Mr. Anderson, you know what they say about not crying over spilled milk!”

Nellie winked at Lorna, who smiled in spite of herself. Since Nellie had been posted to their farm two years ago by the Women’s Land Army, Lorna had come to love her like the older sister she’d never had, though even Lorna could not deny that Nellie was as clumsy as clumsy came. Yet Nellie had an unshakable confidence that Lorna’s father, and indeed every other man within fifty miles, would be putty in her hands if she flashed him her most dazzling smile. And she was usually right.

Nellie picked up the pail and sauntered back into the milking parlor with Caddy trotting in her wake, the border collie puppy following like a black-and-white shadow in case of further delicious catastrophes. Caddy’s mother, Canny, gave a soft yelp, but the little dog still disappeared hopefully after Nellie.

Lorna’s dad shook his head with an exasperated sigh, and Canny sniffed at his hand, as if to commiserate with him about the youngsters of today.

Lorna’s dad gave his dog’s head a quick pat, then took the yard broom from Lorna and starting sweeping ferociously.

A screech of brakes made Lorna turn. A truck was pulling into the yard, but it was not one of their regulars from the feed merchant or the dairy. This one was painted in army green, and a dozen men in dark uniforms perched on benches in the flatbed at the back.

Lorna’s father stopped sweeping and raised his eyes heavenward. “Thank the Lord!” he said. “At last, someone to save me from all you women!”

“Dad?” Lorna said. “Who are—?”

Some of the men were looking around at the farm buildings, others stared at the floor. Some looked directly and unnervingly at her.

“They’ve sent a new man to work on the farm,” Lorna’s dad said, one hand squeezing her shoulder, “but it’s nothing to concern you just now. Anyway, don’t you have an exam this morning?”

Lorna opened her mouth to tell him that calculus could wait. She was almost eighteen, and when she left school in June, she’d be helping him to run the farm, so he ought to be telling her what this was all about. But before Lorna could say anything, a hugely muscled British soldier climbed down from the truck driver’s seat. He had three stripes across the straining arm of his uniform. A sergeant, she realized, just like her oldest brother, John Jo. For a moment, Lorna wondered where her elder brother was right then.

As her father walked toward the sergeant and the truck, a thickset man whose head was closely shaven but whose chin was not called out. He waved at Lorna and said something to her, his voice harsh and guttural. Even if she didn’t understand him, she recognized the language from the newsreels, and her heart leaped to her throat. He was speaking German.

He called again, and some of the others laughed. Suddenly Lorna felt exposed and awkward, and then the familiar burn of a blush began to creep up her neck.

The sergeant dropped the tailboard down with a clatter, startling the three cats sidling toward the milky cobbles.

“Army’s been puttin’ up proper fences over at Gosford for a week or so now,” he said, “gettin’ the camp secure for these blokes. I don’t know why, though. It’s not like they’ll be chained up or nothin’. Too busy workin’ for their keep, from what I hear.”

He beckoned someone forward with a stubby finger. “Vogel! Your turn, Sunshine, down you come!”

Lorna grabbed at her father’s sleeve while not taking her eyes from the men in the truck. Then her dad was growling in her ear. “Stop gawping, girl, and go!”

“But they’re Germans,” she said. “The enemy! You can’t be bringing enemy soldiers onto our farm, Dad. No!”

“They’re prisoners of war now, not soldiers. Sure, that Mr. Hitler is the devil in jackboots, but the war is over for these chaps. And since they’re fit and able young men, they can damn well do a man’s work around this farm—”

“But Dad!” Her annoyance now obscured her embarrassment. “We’re coping just fine—”

“—until your brothers come back.”

“If they ever come back.”

Even as she said it, Lorna knew she’d overstepped the mark, and she hoped her father hadn’t heard.

He had.

“Do not tell me how to run my farm!”

He pointed deliberately in the direction of the village and the school. As Lorna began to argue, a prisoner—had the sergeant called him “Vogel”?—jumped down from the truck, stumbling as he landed, his back to them. He quickly righted his balance. Tall and skinny, his dark gray uniform didn’t fit him. The pants were baggy and too short, and the jacket swamped his gaunt frame. He had the same haircut as the others, shaved close, and his neck was scrawny and pale. He was just a boy, and it looked as if a puff of wind would blow him away.

But then the boy turned toward them and Lorna could see a high cheekbone and strong jawline. All right, perhaps he was more a man, but still …

Then he faced them full-on, and Lorna’s irritation was instantly extinguished, her shock catching her throat.

Half the boy’s face was gone.

No, that wasn’t quite right. His face was there, but from his left temple to his chin, across his cheek and down the left side of his throat, the pale skin had been burned away, leaving raw red scarring, tight and shiny. The flesh was puckered into the knotted remnants of an earlobe, and his left eye was stretched out of shape, round elongating to oval.

Lorna was horrified. What had happened? What had done that to him? She didn’t know what she’d been expecting, but not that. And then an awful thought struck her. Had this terrible damage been inflicted by a British soldier like John Jo? Lorna felt sick at the thought, but still she could not look away.

“Christ Almighty!” her father muttered.

Then the sergeant walked in front of her, and the spell was broken.

“Don’t look so scared, love, he won’t bite.” He seemed to find her discomfort amusing. “Well, not until he knows you better. Ain’t he a horrible sight?”

Lorna glanced again toward the prisoner. Had he heard that?

The sergeant chuckled.

“Don’t worry, love, he doesn’t speak a word of the King’s English. None of ’em do.” He gestured to the German. “Doo haff nine English, eh, Fritz?”

Was that even German?

The prisoner stood straight and still. His expression—or as much of it as she could interpret from the undamaged side of his face—was impassive. A mask. Perhaps the driver was right, and he hadn’t understood the insult.

As the sergeant gave them a mock salute and clambered back into the truck, Lorna struggled to remember what she had been saying before that awful scarred face had forced everything else from her mind.

As the army truck reversed across the farmyard, Lorna forced herself to look at the soldier again. He was glowering—maybe—the undamaged side of his forehead creased into a frown, but really, what expression could she ever hope to read there?

The rumble of the truck faded into the morning chill, and Lorna’s father rubbed his hand over his face. For all his gruffness and bad temper with Nellie, he suddenly looked very weary. Had he been as shocked as Lorna?

Her father walked to where the German waited. “I’m John Anderson and this is my farm,” he said, slower and louder than necessary. “I have two boys of my own away at the war, so you’ll work in their place.”

The prisoner appeared to be listening politely, even if he couldn’t understand the words. He did, however, give Lorna’s father a curt nod.

“You don’t need to bow to me, son, just do your work. Oh, and this is my daughter,” Lorna’s father said as he saw she was still standing behind him, “who should be in an exam room right now.”

But Lorna barely heard what he said. The German was looking at her, and Lorna shivered. His eyes were steel gray, glinting silver, hard and cold and angry.

Then his gaze fell to her school uniform and woolen stockings, her milk-and-muck-spattered shoes. The right, undamaged side of his face rose in a sneer.

Or was it a smile?

No, definitely a sneer.

He looked up again at Lorna and gave her one of those curt nods. Then, without another look in her direction, he followed her father, leaving Lorna alone in the yard.

The rooster crowed again, as if it were already time for—

School! The bloody exam! Lorna was late and Mrs. Murray would kill her. As she grabbed her coat and schoolbag from beside the gate, she scraped her knuckles on the wall and had to suck at the graze to stop it bleeding as she took off running toward the shortcut past the church. The path would be muddy, but her shoes couldn’t get much filthier than they were already.

As she ran, Lorna resolved to forget about the German for now, to forget that her dad had invited the enemy onto their farm, into their home. But still, there was the way the German had looked at the mess on her shoes, his burned face, his angry eyes, and his distorted smile—no, his sneer—and somehow that made her run all the faster.

Two (#u69f1a894-96a0-5325-941d-ea07400e07b2)

BIG NEWS! Need to talk later.

Lorna waited while the ink dried on the scrap torn from the back of her exercise book, then slid it across the desk and under the page her best friend, Iris Robertson, was doodling her latest dress design on. The calculus paper hadn’t been anywhere near as hard as Lorna had expected, and she and Iris had both finished it with plenty of time to spare. Now she was bored.

Iris glanced at the note and moved to slip it into her cardigan sleeve. Before it was hidden, however, long fingers reached out and took it from her hand, making Lorna and Iris both jump. Mrs. Murray stood over them, fanning herself with the note, then gave her head a quick shake of disapproval and returned to the front of the classroom.

Lorna had another twenty minutes of staring out at the heavy cloud that seemed to smother the high classroom windows before Mrs. Murray called an end to the examination. The teacher squeezed between the tightly packed desks to collect the exam papers into two piles—calculus from the older students like Lorna, and algebra from the younger ones. It had been close to chaos when the two classes had merged after Mrs. Duffy had run off to join the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force the year before, but Mrs. Murray’s rod of iron had soon brought an almost military discipline to the room.

As Mrs. Murray passed by Lorna’s desk, picking up the papers, she paused.

“Would you join me in the hallway please, Lorna?” she said. “I need a quiet word with you.”

Damn! It was only a note. It wasn’t like she’d been cheating.

Lorna exchanged glances with Iris before reluctantly pushing back her chair and walking slowly to the front of the classroom. Esther Bell snorted loudly as Lorna passed her, but Lorna paid no attention. Esther got told off more than Lorna ever did, anyway, and it was because of people like Esther that Lorna was counting down the days until she graduated from school. Only then would she be spared the trial of seeing Esther each day.

“Class! Get out your English notebooks and start on the assignment on the blackboard,” Mrs. Murray ordered as she opened her desk drawer and took out some papers. “We’ll break for lunch at noon, as usual. In the meantime, I do not, I repeat, do not want to hear one peep from in here.”

She walked into the hallway, holding the door open for Lorna to follow.

Lorna glanced back at Iris, but she was gazing at William Urquhart with that ridiculous look on her face.

Lorna pulled the door closed behind her and faced her teacher. “Look, Mrs. Murray, I’m sorry about the note, but it’s not like I was—”

“Oh, shush,” said Mrs. Murray, waving away Lorna’s defense with her hand. “This isn’t about the note, this is about you. Now, I’ve been thinking again about you applying to the university for next year.”

Lorna wanted to groan. It would have been better for Mrs. Murray to scold her for the note passing than this torture. “Mrs. Murray, you know that my father—”

“Yes, I know you’ve told me before that he’s not keen on you continuing your education after you get your school certificate in June, so perhaps I need to go and talk to him—”

“No! Really, you don’t have to do that.” Lorna tried to calm her voice. “He needs me at Craigielaw, that’s all.”

Mrs. Murray studied her for a moment.

“Well, I’m not so sure,” replied Mrs. Murray. “You have too bright a mind to rot on a farm your whole life, and I’m sure he knows that. Remind me of your birthday, dear. April, isn’t it? That’s when you’ll legally become an adult. So you’ll have to find a way to make him understand that you’ll be responsible for your own choices after that. And who knows, perhaps your dad might just surprise you.

“Now, as I’ve said before, I’d love to see you at the university, but if you won’t, I mean, if your father won’t agree to that, what about Mr. Dugdale’s Secretarial College?”

She held out the papers in her hand to Lorna.

“They offer all sorts of classes, like shorthand and typewriting, and I hear that Dugdale graduates are very highly regarded. You’d be able to go up to Edinburgh on the train each day, and the college is just a short walk from Waverley station.”

The top sheet, with a fancy crest, was a letter thanking Mrs. Murray for her recent inquiry, and a printed brochure lay underneath.

“It’s amazing what girls these days can do with good secretarial skills,” Mrs. Murray continued. “And secretaries have all sorts of travel opportunities, you know. Glasgow, Aberdeen, or even Birmingham.”

Lorna tried not to sigh. Mrs. Murray made it sound like Birmingham was the most exotic place on earth, but Lorna knew it wasn’t even as far away as London, where Sandy, her other brother, worked in the War Office. And it certainly wasn’t anything like Paris or New York, or Cairo or Bombay, or any of the other places Lorna and Sandy had talked about traveling to. But right now, Lorna couldn’t think of going anywhere.

She knew she was virtually an adult now, and she would have to make some decisions soon about what to do with her life, but she couldn’t even think about leaving her father alone at Craigielaw, at least not until the war was over and the boys came back. Then she might think about secretarial college. Maybe. But who could guess when the end might come? When the war was declared in September 1939, everyone had said it would all be over by Christmas. It was now 1945; six Christmases had come and gone since then. How many more …?

And was secretarial college enough for Lorna? What about her dreams to travel?

“Lorna?”

Lorna realized that Mrs. Murray was still waiting for an answer.

“Lorna, have you got something on your mind this morning?” Mrs. Murray suddenly appeared concerned. “Is everything all right at home, dear? Are your brothers …?”

Mrs. Murray’s lashes were glistening wet.

“I mean,” the teacher tried again, “have you perhaps had some news from the regiment?”

Then Lorna understood what she was really asking. Mrs. Murray’s only son, Gregor, was one of John Jo’s best friends—and Lorna’s favorite by far—and was serving with him in the same regiment of the Royal Scots. Her husband had died when Gregor was quite young, so once Gregor joined up, she’d been left on her own.

“Oh no, Mrs. Murray, nothing like that. We had a letter from John just yesterday, and he’s doing fine. He moaned about the cold and the food and all the usual stuff but seemed to be fine otherwise. I’m afraid he didn’t mention Gregor in his letter, though.”

Mrs. Murray’s anxious expression shifted to relief, then to disappointment.

“But I’m sure Gregor will get in touch soon. I’ll write back to John Jo this evening and I’ll have him tell Gregor you were asking after him, if you like.”

Mrs. Murray’s mouth smiled, though her eyes did not.

“That would be kind, dear, thank you. Gregor never was one for writing, was he?”

Mrs. Murray gave a not very convincing laugh and dabbed at her cheeks with a white lace hankie she had drawn out of her skirt pocket.

“Come on then, Lorna, back to work, and please think about what I’ve said.”

Lorna tried to hand back the college papers, but Mrs. Murray didn’t take them.

“Keep them, dear.” Mrs. Murray patted Lorna’s hand. “You never know what might be around the corner. And if you would be kind enough to pass that message on to your brother, I’d be very grateful.”

Mrs. Murray pulled open the door of the classroom and, squaring her shoulders, walked inside.

“George Brown! Sit down! Can I not leave this classroom for one minute?”

As Lorna returned to her desk, Iris tore her eyes away from William Urquhart to look at Lorna questioningly, but Lorna just shrugged back. The secretarial college papers crinkled inside her cardigan as she sat down. Her secret for now.

As Mrs. Murray wrote again on the blackboard, Iris nudged Lorna’s elbow.

“What news?” she whispered.

Lorna shook her head and mouthed, “Later.” As soon as they were alone after school, she would tell Iris all the details of that morning. After all, Lorna and Iris had shared everything since they were tiny.

It was strange, though; as the day wore on, Lorna became aware of an unfathomable desire to keep the arrival of that awful damaged stranger to herself.

Three o’clock finally came. William Urquhart stood up from his desk with an officious clatter. William was the son of the parish minister and was also Aberlady School’s head boy. As such, he was responsible for ringing the big handbell by the front door to signal the beginning and the end of the school day.

As he passed by, William winked at Iris.

Iris giggled and blushed.

Lorna groaned.

What was Iris thinking? Of all the boys she could set her sights on, why did it have to be pompous William Urquhart?

As the first heavy peal of the handbell sounded from the front door, Lorna was on her feet, signaling to Iris to be quick. Iris clearly had other ideas. As everyone else surged from the room, she very carefully flipped down the lid of the inkwell set into her desk, wiped her pen nib on a cloth rag, and placed her workbook into her desk, lining it up carefully on top of the pile already inside. Then she took a hairbrush from her schoolbag and began tugging at the knots in her messy brown curls, pulling the hair straight down her shoulder with the brush, only to have them bounce back up again, looking no tidier than when she started.

“Come on, Iris, hurry!” urged Lorna.

“I’m coming, I’m coming,” said Iris, stuffing the brush back into her bag. Suddenly, her eyes lit up as she looked behind Lorna.

William Urquhart was standing right there, uncomfortably close. He bowed at the waist—not a brief nod like the German’s, but a full bow—and Lorna had to step back to avoid him touching her.

“Have a good afternoon, ladies,” he drawled.

So full of himself!

He straightened up and brushed past Lorna. When he reached Iris, he lifted her left hand to his thick red lips and kissed the back of it.

Iris giggled again.

Lorna shuddered. Who did he think he was, Errol Flynn?

“Good afternoon to you, William,” Iris purred. “I’ll see you in the morning. I’m looking forward to it already.”

William oiled his way out of the classroom. As they followed him out, Lorna glared at Iris but said nothing until they were on the street. There she bent double and pretended to retch into the gutter.

“What are you doing?” asked Iris.

Lorna stood up.

“Oh, William, I’m looking forward to it already,” she cooed sarcastically, wiggling her hips in an impression of Iris. “Iris, you can’t be serious.”

“But he’s so dashing.”

Lorna scoffed.

“We’ve always said he looks like a young Tyrone Power, though.”

“No, Iris, you’ve just started saying that.” She glanced around in case William had reappeared. “I’ve always said that he looks like a snooty, stuck-up slug.”

Iris pursed her lips in that infuriating motherly way, and Lorna knew what was coming—another lecture about how Lorna didn’t appreciate William’s better traits.

“No, you’re wrong, he’s not stuck-up. He’s very intelligent and really, very mature.”

“Did he tell you that?” Lorna didn’t want to sound nasty, but sometimes she despaired of Iris, she really did. William had only asked Iris out for the first time the other day, but she was acting like they’d been an item for years.

“Actually, it was his mother who told me,” Iris said without irony, ignoring Lorna’s snort of derision. “And he’s already been offered a place at Edinburgh University for September to study law. And then he’ll do his postgraduate doctorate in theology so he can become a minister like his father. Of course, William has ambitions beyond a tiny parish like Aberlady. He’ll have one of the big churches in Edinburgh, even St. Giles Cathedral, perhaps. He’s very driven, you know, and I very much admire that in an honorable man.”

Lorna had heard enough.

“An honorable man? Iris! Listen to yourself. Don’t you remember how upset you were just last year when he was so mean and patronizing about your Jane Austen project? And about your singing, and my drawing? Are you telling me he’s really changed that much?”

“He has, Lorna. You’re just not giving him a chance,” Iris muttered through pursed lips. “He’s changed since then. And you are being quite mean and patronizing yourself right now.”

“I am not. I’m just trying to get you to see sense,” Lorna retorted. “Anyway, what about John Jo? My brother will be heartbroken when he finds out you’re not pining for him anymore.”

“That was just a girlish infatuation,” Iris said haughtily. “This is true love. William and I will be together forever.”

“Forever?” Lorna scoffed. “But won’t Saint William be called up when he turns eighteen in June? Chances are that by September he’ll be off to the army, not to university.”

Iris looked uncomfortable.

“Yes, possibly,” she conceded, “but his mother seems sure that with his poor eyesight and foot problems, he won’t have to go. A deep mind like William’s would be much more suited—”

Lorna snorted.

“Poor eyesight? He doesn’t even wear glasses. And I don’t think having stinky feet can keep you out of the army. It certainly didn’t work for my brothers.”

“Stop it, Lorna! His eyes are very sensitive, Mrs. Urquhart says. And apparently, the Urquharts know a colonel up at Edinburgh Castle, and she’ll have a word with him when William’s call-up papers arrive. And for your information, William does not have stinky feet.”

“Did Mrs. Urquhart tell you that too?” Lorna tried not to snap. “Come on, Iris, can you not see that his mother would do anything to keep her little baby at home instead of letting him out to play with the rough boys?”

Lorna couldn’t stop the bitterness creeping into her voice. She didn’t mean to pour scorn on a mother’s fears. Lorna knew what it was to lie awake at night imagining every bomb or shell or bullet that might hurt John Jo or Sandy, and she wouldn’t wish that on anyone else. But if her brothers were risking their lives, then why should William-bloody-Urquhart stay safely at home?

“Lorna, that’s not it at all.”

Iris sounded hurt. Lorna didn’t care. She was on a roll.

“No? And what does Sweet William have to say about all this? Is he happy to have his mother weasel him out of doing his duty?”

“No, actually.” Iris’s voice was suddenly barely a whisper. “William seems to be quite excited about joining up, even though that means he’ll have to leave his mother and father behind … and me.”

All Iris’s tight-lipped motherly condescension had vanished, and tears sparkled in her eyes.

“Oh, Iris, don’t.”

Iris wiped at her face with her sleeve.

“You just don’t understand,” she sniffed, “what it’s like to be in love.”

Lorna was stumped. She would have told Iris off, but her friend looked so sorrowful, Lorna just sighed and wrapped Iris into a hug.

“Oh, come on, silly, don’t cry. The war could be over by then, and we’ll get all our boys back, the sweet ones and the rough ones. Maybe William won’t have to go at all.” Lorna pulled out her handkerchief and handed it to Iris. “Anyway, I have something important to tell you, so please come for tea.”

Iris managed a wan smile and sniffed.

As they walked toward Craigielaw, Lorna told Iris about the new arrival that morning, and gradually, Iris seemed to recover her humor. Within minutes, she was firmly agreeing with Lorna and was suitably appalled by the news. Hadn’t they both always detested Germans? How could it be patriotic to let the enemy run amok on British soil, even if they were prisoners?

“I know that Dad and Nellie could do with more help”—Lorna picked up the rant where Iris left off—“especially since Old Lachie had to retire from the sheep before Christmas. But is there really no other option than dumping bloody Germans on us?”

“Apparently”—Iris sounded like she was spilling a secret, her voice dropping low—“the prisoner who was delivered to Esther’s farm this morning was really old and fat, and Esther’s dad was not happy. He said the chap would be worthless for any heavy work on the farm, which is what he was needed for. And Esther says their Land Army girl is useless and the size of a sparrow, not like your Nellie at all.”

“Nellie’s hardly enormous,” said Lorna.

“No, but she’s strong and she knows about engines and stuff.”

“Yes, but she’s still a woman. And apparently my dad would rather have a German on the farm than another woman, even a German who looks like that.”

“Looks like what? Is your prisoner old and fat too?”

“Not exactly …”

“Young and fat?”

“No …”

“Well, is he young and handsome then?”

“Not exactly …”

“He is, isn’t he? You think he’s handsome!”

“Oh stop!”

“You do, don’t you? You fancy a German!” Iris cried.

“Iris, shhhh! I mean it, stop! He is young but … oh, it’s awful. He’s been … burned … his face … it must have been awful.”

Lorna could picture him again: the tight angry, brilliant pink skin contrasting with eyes the color of snow-laden clouds, and the sneer that tweaked the corner of the disfiguring mask. Lorna wondered for the first time how bad his pain had been.

“Oh my goodness, no!” said Iris, looking more thrilled than horrified. “That’s dreadful! Well, I suppose it’s dreadful, isn’t it? I mean, he is a German, so maybe he deserved it … not deserved it exactly, but … oh, you know what I mean.”

“Iris! Just because someone’s a German doesn’t mean he deserves to be hurt so badly.”

“But you hate Germans.” Iris looked genuinely puzzled. “Aren’t you pleased that this one’s been hurt?”

“Well, yes … no … maybe … I mean, yes, but when you’ve got a real one standing right in front of you and the damage to his face is so terrible, well, it’s … different. Somehow.”

Lorna realized only then that her initial revulsion was passing on, allowing pity to creep in behind. She looked at Iris, expecting to see a reflection of her own discomfort, but Iris was smiling.

Iris leaned in close, her face eager.

“But you still haven’t told me,” she said in a loud whisper, “would your German have been handsome if he wasn’t so … you know?”

“Iris!”

Three (#u69f1a894-96a0-5325-941d-ea07400e07b2)

Mrs. McMurdough had her coat on to leave when the girls walked into the kitchen. On the range behind her, a huge pot of stew simmered deliciously.

Lorna threw down her schoolbag and wrapped her arms around the housekeeper from behind. Taller by several inches now, Lorna kissed the old woman on the top of her head as she hugged her.

“Mrs. Mack,” said Lorna, who had seldom heard the housekeeper called by her full name, “that smells wonderful.”

Mrs. Mack had looked after Craigielaw since Lorna’s mother died when Lorna was a toddler. She came in from the village every day to cook, clean, and care for the family. Now that the boys were away and Lorna was older, however, Mrs. Mack would leave when Lorna got home from school and go look after her own grandchildren while her daughter Sheena worked the late shift in the aircraft repair factory at Macmerry. Before she went, however, Mrs. Mack always had a meal ready for Lorna to serve up to her father and Nellie.

“And a good afternoon to you, too!” Mrs. Mack turned round and hugged Lorna back, but only for a moment. “But just look at my floor!”

Lorna stepped back. A trail of mud ran from the door to end at her filthy shoes.

“I did not spend half the morning on my poor old knees scrubbing, just for some young besom to drag mud across it. Out you go, and take those filthy shoes with you.”

She gave Lorna a playful shove toward the door.

“Oh, and Iris is here, how lovely. Actually you’ve saved me a trip, dear. I’ve some cotton curtains that I want made into pinafores for my granddaughters.” Mrs. Mack barely paused for breath. “I’d sew them myself, but my fingers aren’t up to stitching anymore, and I know that you and your mum would do a lovely job on them. I saw the party frocks you did for Mrs. Gunn’s twins. Very pretty. So shall I pop the material in to your mum on Sunday after church?”

“We’d love to help, of course,” replied Iris, “but we won’t be home after church on Sunday. The minister and Mrs. Urquhart have invited Mum, Dad, and me over to the Manse for Sunday dinner.”

Mrs. Mack’s eyebrows lifted slightly.

“Sunday dinner at the Manse with the minister? My, how grand!”

“Well, now that William and me, I mean William and I, are stepping out together …”

Mrs. Mack’s eyebrows rose even more.

“Now, that’s some news I hadn’t heard about,” she said, looking pointedly at Lorna.

“Well, it’s only been a week or two, eleven days actually,” continuted Iris, “but we are very keen on each other. He’s very good-looking, don’t you think? Just like a young Tyrone Power, that’s what we’ve always said.”

Lorna vigorously shook her head behind Iris’s back to make sure the housekeeper knew that she was not part of that “we,” and Mrs. Mack suppressed a smile.

“Well, I don’t get to the pictures very often these days, so I wouldn’t know about that,” Mrs. Mack said, “but I’m sure you’re right.”

“And he’s very clever too, and very moral. So we’re doing things the right way, and that’s why our parents are meeting on Sunday.”

“Meeting on Sunday?” Mrs. Mack burst out. “But your folks and the Urquharts have known one another for years. Decades even. Didn’t Reverend Urquhart baptize you and Lorna and every other bairn born in the village these last twenty years?”

“But it’s different now.” Iris was pursing her mouth again. “They’ll be meeting for the first time as the parents of a couple who are stepping out. Don’t you see?”

Behind Iris, Lorna picked up an imaginary noose and mimicked hanging herself. She could see Mrs. Mack was struggling not to smile.

Suddenly, Iris spun around, catching Lorna with one hand in the air.

“What are you doing, Lorna?” she demanded.

“Sorry,” Lorna choked out. “You know I was only kidding.”

“You’re just jealous because I have a young man now.” Iris put her hands on her hips, like an angry old man in the cartoons, which amused Lorna even more. “And you’re even more jealous because it’s William.”

Lorna and Mrs. Mack were both laughing now, even as Iris’s voice rose with irritation.

“I always knew you secretly liked him. Well, bad luck, Lorna, he’s mine now, and you can just die an old maid if that makes you happy.”

Iris furiously buttoned up her coat.

“And if you ever want to escape off this farm like you say, Lorna Anderson, then perhaps you should just grow up a bit and find someone to marry who’s as good and as clever and as driven as my William.”

With that, Iris flounced out of the door.

“Iris!” called Lorna. “I’m really sorry. Come back! I was only teasing.”

But Iris was gone. Lorna didn’t go after her because Iris regularly flounced out after one disagreement or another, and they always made up at school the next day. Lorna rolled her eyes at Mrs. Mack, who shook her head.

“That wasn’t very kind, you know,” said the housekeeper, “but my, it was funny.”

“She’s right, though,” replied Lorna. “I probably will die an old maid, unless that German slaughters me in my bed first, just to put me out of my misery. Wait, do you even know about the German yet?”

“Aye, I’ve met the German, but what are you havering about?” said Mrs. Mack with a snort. “That young laddie hasn’t enough gristle in his meat to choke a chicken, let alone to murder you. Did you not get a look at him? There’s nothing to him. Hasn’t had a square meal in months, judging by the speed he wolfed down the soup and dumplings I fed him at dinnertime.”

“You gave him his dinner?” Lorna was startled.

“Of course I gave him his dinner.” Mrs. Mack looked perplexed. “Why wouldn’t I? The lad has to eat if he’s expected to do a day’s work. Or should I be giving him gruel like he was in the workhouse? And a hunk of stale bread every Friday if he’s very lucky? Oh my goodness, but you’re a hard one.”

“I’m not hard, I just don’t see why …”

Mrs. Mack was looking at her steadily, one eyebrow raised as if Lorna’s words were simply proving her coldheartedness.

“So where is he now?” Lorna asked instead.

“They went over the back field after dinner,” Mrs. Mack replied, turning back to stir the stew. “One of the heifers got herself hooked onto the fence. And our Nellie’s getting the cows in for milking. She’ll likely be in begging a cup of tea before you can say ‘Where’s the shortbread?’”

Sure enough, within minutes, Lorna heard the lowing of the dairy cows as they shuffled toward the milking parlor, as they did morning and night.

Lorna went to the back door. Nellie was stamping along behind the cattle.

Like Nellie, dozens of Land Girls were working on farms around East Lothian, doing the farmwork left by men called up to fight. When she’d first arrived from London, aged eighteen, Nellie had never even seen a cow before, but soon it was like she had been born into farming. Not only was she now a trained tractor mechanic, more importantly, Nellie had beguiled the cows into their best milk production in years and was clearly happier in Aberlady than she had ever been in London.

Petite but buxom, Nellie was definitely the only Land Girl that Lorna had met who could wear the uniform of a thick green sweater and beige jodhpurs without looking like she was hiding a sack of potatoes up her shirt. And Nellie used her curves to great effect, by all accounts, in the pubs and dance halls on her nights off. She flirted unashamedly with local men and visiting servicemen alike and openly admitted that she was looking for someone who could offer her a better life after the war than she’d had at home in London before it.

When Nellie caught sight of Lorna through the kitchen window, she waddled over as fast as she could in rubber boots at least two sizes too big for her tiny feet.

“So what do you think?” Nellie said in a loud whisper.

“About what?”

“About the new chap, duckie. Didn’t you see him?”

Lorna pretended not to understand.

“For Gawd’s sake,” said Nellie, “that new young lad, the German, with the face, you know. That poor boy. What a mess! I could scarcely look at the poor blighter.”

Lorna couldn’t think how to reply, but Nellie didn’t seem to need her to.

“I don’t know about you,” Nellie continued, “but I’ll be locking my bedroom door at night, I will, if they’re going to let these Jerries roam around the place.”

“They’re not roaming around,” said Lorna, unreasonably irritated even though she’d been thinking the same thing, “and he’s not going to be here at night. He’ll go back to the camp at night to be locked up again. At least, that’s what they said.”

“Fingers crossed they keep those gates locked tight then, eh?” Nellie said. “I’ve been quite happy up to now keeping as far away from German soldiers as I can get.”

She wandered back toward the milking parlor, slapping the trailing cows on their rumps to speed them up.

“Good to know there’s one kind of soldier you’d stay away from, Nellie,” Lorna muttered to herself as she walked back to the kitchen.

The next morning, as Lorna cleared up the breakfast dishes, the dogs began barking at an approaching truck. Knowing it must be dropping off the prisoner from Gosford, Lorna rushed to put her coat on and grab her schoolbag. She needed another look.

The yard was murky as Lorna pulled the door shut behind her. The blackout curtains ensured no light escaped into the yard, and the early sun had not yet broken through the clouds that had rolled in overnight. As she put her gloves on, Lorna heard the cows stamping and Nellie cursing in the milking parlor.

The truck’s tailgate slammed, and around the back of the truck came the German boy, an excited flurry of sheepdogs around his knees. He bent over and rubbed the dogs’ necks.

Traitors! They didn’t greet her like that anymore.

Even in this light, it was clear he was young for a soldier, barely older than some of the lads at school, so maybe eighteen? Nineteen at most. The knitted hat he wore over his shaved head was pulled lower on the left side, and his uniform was hidden now under some brown coveralls. Familiar brown coveralls, with an elbow patch and a torn pocket.

Lorna recognized them suddenly as Sandy’s. Had the prisoner stolen them? No, that was silly, he wouldn’t be wearing them around the farm if he had. Which meant that her dad, or perhaps Mrs. Mack, must have given them to him. What right did they have to give away her brother’s belongings when he was gone? And to a German, no less.

As he walked toward the barn, he rubbed his hands together, his fingers fine-boned, almost delicate. Not the hands of a farmer, and certainly not hands that were used to the frigid air of Scotland in February. Lorna noticed he had no gloves, so at least Dad or Mrs. Mack hadn’t given him a pair from the boys’ bedrooms. The enemy didn’t deserve to be warm, no matter what Mrs. Mack said, and no matter what injuries he’d suffered.

He stuffed his hands deep into his pockets and hunched his shoulders up to his ears. He looked … was forlorn the right word?

In spite of herself, Lorna suddenly felt almost sorry for him.

As the truck reversed, she stepped out of the shadows, her school shoes clicking on the cobblestones. The German saw her, and for a second or two, neither of them moved.

A frown creased the skin on the right side of his forehead, and as before, Lorna found herself mesmerized by the dreadful damage to his face.

Then embarrassment overcame fascination, and Lorna looked down at her shoes, still muddy from the day before. When she looked up, the frown had smoothed out, but the tug at the right side of his mouth was there again. That same sneer. Except, today, it did look more like he was trying to smile. Tentative, perhaps, but still, it lightened his face, filling out the gaunt flesh of his right cheek, though the left remained tight and static. He gave her a nod, and instinctively, Lorna nodded back, feeling suddenly shy.

Why should she feel shy, though? It was her farm, after all, and he was the stranger. She needed to be assertive.

“Good morning,” she said, raising her voice as her father had done. “I. Am. LORNA. ANDERSON.”

She drew out the sounds of her name, making every letter clear. She pointed her finger to her chest.

“Hello,” the boy said, touching his own coveralled chest with one long finger. “I. Am. PAUL. VOGEL.”

He pronounced his words as clearly as she had, almost mimicking her. His English words were clipped and short.

“Hello,” Lorna replied.

He bowed his little bow again.

“Em …” Realizing she wasn’t sure what to say next, she hoped the poor light might cover the flush that was creeping up her neck.

The German stayed silent. Clearly he was waiting for her to speak. There was no sign of the smile now. But none of the frown either.

“Em …,” she repeated, glancing up at the lightening sky.

When she looked back at him again, his gaze was intent upon her and the smile was back, drawing Lorna’s attention away from the burns. Its curve led her from his mouth up to his eyes, which sparkled.

Lorna suddenly felt furiously guilty about noticing that. Surely noticing an enemy’s sparkle was tantamount to treason. She was betraying John Jo and Sandy and Gregor and all the others by even noticing such a sparkle, wasn’t she?

And anyway, what right did this prisoner have to be smiling and sparkling at her?

At that moment, “Yoo-hoo!” rang across the yard. Mrs. Mack appeared through the gates to the lane, carrying as always her big carpetbag and waving her umbrella at them before heading toward the house.

Lorna straightened her shoulders and lifted her chin.

“I have to go to school now,” she said slowly, pointing imperiously in the direction of the village and then at her school tie. “To school.”

The prisoner nodded.

“Ja,” he said, “zur Schule.”

She nodded. “Yes, to shool, I mean, school.”

He smiled again, or at least, that’s what it looked like. “I hope that you have a very good day, Fräulein Anderson, and that your teachers are not too … strict?”

He spoke slowly and deliberately, seeming to taste each word, and his voice lifted at the end as if to question whether he had used the right word.

Lorna stared at him.

“You speak English!”

“Yes, a little.”

“But why didn’t you say so?”

“Because you did not ask. And I do not speak it well. But I will become better perhaps. Yes?”

“Yes, of course … em … I mean, no.” Lorna swallowed and tried again. “I mean your English is very good, and I’m sure it will get better, while you’re here, talking, with my dad. Though he speaks Scottish English, really, not English English.”

Lorna knew she was babbling, so she stopped talking before she said anything else embarrassing. But then there was silence, and Lorna hated silences.

“So did you learn English at school?”

“No. My uncle is a farm … a farmer … in Germany. The wife of my uncle is—or was—an English lady, and I take my holidays on the farm with him when I was a schoolboy. So I give help to my uncle with the sheep and my aunt gives me, gave me, lessons to speak English.”

Although he looked frustrated at having to correct his grammar, Lorna had no problem understanding him. Then something else struck her.

“So yesterday, when the sergeant who brought you here said you … called you …” She couldn’t bring herself to repeat it. “That is, you understood him?”

The German shrugged.

“I have heard more … worse, I think,” he said.

From somewhere came a sharp whistle. The dogs’ ears pricked and they pelted toward the sound, vanishing around the corner of the barn.

“I think that your father calls to me also,” said Paul. “Auf Wiedersehen, Fräulein Anderson. Good-bye.”

He raised his hand in a wave, and without thinking, Lorna repeated the gesture.

Stop! He shouldn’t be this friendly. She couldn’t be this friendly. He was a German, after all.

“Wait!” she said. “I think you should know that people aren’t happy that Germans are working on our farms.”

Paul said nothing.

“I mean”—Lorna felt shaky under his intent gaze, but refused to be put off—“how could anyone here be happy about having a camp full of Nazis on our doorstep?”

Paul stiffened.

“Fräulein Anderson”—his voice was sharply polite—“I am German, yes, but I am not a Nazi. There is a difference, and one day I hope you understand that.”

His eyes were flint hard. With a sharp click, Paul brought the heels of his boots together. Then he spun on his toes and walked smartly away, leaving Lorna reeling.

As Lorna watched him go, Mrs. Mack came back out of the kitchen door, tying her apron strings around her waist. “So he’ll not murder us in our beds in the name of the Fatherland, then?”

Lorna faced her, still rattled. “Did you know he speaks English?” she asked.

“Aye, I did notice that.”

“But why didn’t you tell me?”

“Because you never asked.” Mrs. Mack was smiling at Lorna’s confusion. “He seems a nice enough lad, though.”

“But he speaks English,” Lorna said, suddenly serious. “He might be a spy or something.”

“Oh, I don’t think we need fret now, do you?” Mrs. Mack replied, crossing her arms under her bosom. “And what do you think our John is out there doing, knitting sweaters? All these boys are just doing what their countries ask of them. But this lad’s war is over now, and please God it will be over for us all very soon. What harm can he do stuck on this farm with us anyway? I trust him not to kill me in my bed, and I think you should too.”

Mrs. Mack suddenly clapped her hands.

“But we’ve no time for chatter. You’ve a lesson to get to, and I’ve a midden of a kitchen to clean. So get off with you!”

Perhaps Mrs. Mack was right and Lorna was overreacting. Maybe.

And actually, the prisoner had seemed quite nice, and not particularly threatening. Well, at least until she’d called him a Nazi. Yes, he was quite nice really. For a German.

Four (#ulink_f181db75-9395-59ed-bcd6-3dbf39bce4f1)

For the next few days, Lorna barely saw the prisoner. The truck dropped him off in the morning, but he had vanished from the yard by the time she left for school. When she got back home, he was away with her father in one of the far fields until he was picked up again in the evening.

And that was fine. Lorna didn’t want to see him anyway.

But even though she still felt queasy at the thought of having an enemy prisoner on the farm, she also found herself watching out for him, taking the longer route home, telling herself she was just enjoying the sunny and crisp winter weather. And she couldn’t help feeling a little disappointed when she didn’t see him.

But really, not seeing him was fine.

It was as if everyone else had forgotten he worked there. Mrs. Mack was no longer around in the afternoons because of her grandchildren, and Nellie had little to talk about except the “cute” new American airman she was “dating”—two of the new American words that Nellie used constantly these days.

And conversations with her father were rare events. He would knock twice on her bedroom door in the morning to make sure she woke up, but was gone before Lorna got downstairs. In the evenings, he came into the house in time to eat his meal in silence as he read that morning’s Scotsman. Then, with a cup of tea or sometimes a small glass of whisky, he sat in his chair by the fire and listened to the evening news bulletin on the BBC.

However, after almost a week of not talking about the German, Lorna realized that she did want to talk about him after all. She wanted to find out why her dad didn’t seem in the slightest bit worried that he was there, and to ask if her dad knew how he had got the scars across his face. But how could she bring up the subject?

One evening after she’d cleared away the dishes, Lorna sat down with her dad to listen to the wireless. She tried to look casual by counting the rows in the woolen scarf she was knitting for the Red Cross collection as she waited for the news bulletin to be over.

For weeks now, the radio news had been full of the Allies’ progress through Europe, chasing back the Germans from France, Belgium, and Holland. That evening’s bulletin reported on more successful bombing raids by the British and American air forces on German cities like Chemnitz, Dresden, and Magdeburg, as well as the destruction of a major bridge over the River Rhine at a town that sounded to Lorna like it was called Weasel.

As the news announcer moved on to more political news from London, Lorna decided she could ask her father now. But, as he so often did, her father had already dozed off in his chair and she didn’t have the heart to wake him. Lorna wrapped the wool around her needles and tucked them away in her knitting bag. Quietly she took the glass from her father’s hand and put it on the table beside him before she tiptoed upstairs.

As she brushed her hair in her bedroom, Lorna tried to put the German out of her mind, but the trouble was, he wouldn’t go.

He’d even appeared in her dreams. The first time, his damaged face had reared up at her and she had run from it, screaming, waking herself as she did. Another night, she hadn’t seen his face at all, but she still knew he was there, watching her. In one dream, she’d clearly seen his face as it would have been, or as it might have been, pale-skinned and clean—and handsome—and then he had been wearing a British sergeant’s uniform like John Jo’s.

And last night, he hadn’t been wearing anything …

Lorna shook her head, pretending to herself that she wanted to rid her mind of that image, and settled her head onto the pillow. Sleep took a while to come.

And it wasn’t as if she were the only person obsessing about the German. Iris seemed even more fascinated by him than Lorna.

Lately, if they walked down to the shops or to the beach after school, Lorna knew it would only be a minute or two before Iris brought him up.

The next day was no exception.

“So what’s your German been doing?” Iris asked, as Lorna knew she would.

Lorna pulled her coat more tightly round her and tucked her chin into the loops of her scarf. They were walking along the edge of the beach, shadowing the winding Peffer Burn, which snaked its way through the mudflats and sandbanks near the village.

“I haven’t seen him,” she said, “and he’s not my German.”

This sent Iris into a lecture about why Lorna should be interested, and what if the prisoner sabotaged the farm, which was what William said was bound to happen. And William also said that …

Lorna wasn’t really listening. Mrs. Mack had often said that Iris could talk the paint off a gatepost, so Lorna knew that as long as she nodded every so often, soon enough the “Threat from the German” lecture would wind down and the “Wonder of William Urquhart” lecture would begin.

Iris suddenly crouched down to retie her shoelace, without once pausing her flow of chatter. Lorna stopped too, and gazed out over Aberlady Bay.

It was a relatively calm day for February, but still freezing cold. The low sun was reflecting off the receding tide, making Lorna shield her eyes with her hand. The dunes of Gullane Point were bathed with golden light, and the exposed sands of Aberlady Bay were striped with ripples and dotted with wading birds, oystercatchers, and curlew, which darted around the huge concrete antitank blocks lining the shore. As an extra barrier to an invasion, an array of tree trunks had been sunk upright into the sand like the rib cage of some rotting dinosaur, but beyond them, Lorna could see fat-bellied seals lounging in what little sunshine was left, oblivious to the chill wind blowing across the water and the looming threat of the war.

“Come on, slow coach,” Lorna moaned, “it’s too bloody cold to hang around.”

“Just give me a minute!”

While she waited, Lorna tugged off her gloves and picked up a pebble from the path, tossing it into the shallow burn with a satisfying splash and a light plink.

“Come on, Iris,” she said, “Dad’ll be wanting his tea.”

Iris stood up, stamped her feet, and stuffed her hands deep in her pockets.

“Well?” she asked Lorna.

“Well, what?” Lorna replied.

“Oh, Lorna, sometimes I think you just never listen!” Iris scolded. “Which dress are you going to wear for the tea dance in Tranent on Saturday afternoon?”

“Tea dance?” Lorna was puzzled. “Saturday?”

“Yes!” Iris sounded like she was addressing a small child. “Dancing, on Saturday, with William and Craig?”

“William and Craig?”

“You must remember! When William asked me out that first time, he said we should all go to the next tea dance in Tranent, as a foursome. Me and William, you and Craig. Remember?”

Lorna realized she did remember, though clearly not in quite the same way as Iris did. When William had cornered Lorna after church that particular Sunday, he had indeed talked about going to the tea dance in Tranent. Lorna had been horrified by the invitation, but William had not appeared to notice. He just waited for her response. Then Iris had bounced up to them—Iris only ever bounced or flounced—demanding to know what they were talking about so secretly. Only at that point did William mention the idea of the two girls making up a foursome with him and his friend Craig.

At the time, Lorna had been under the unspeakable impression that William was asking her out, but Iris had grabbed his arm and excitedly assumed the invitation was for her. And maybe it had been. Either way, Lorna was so relieved, she had put the whole idea from her mind. But now … Craig Buchanan? Not a chance! Craig was so much worse than William. He was very good-looking, sure, but oh God, did he know it. And the way he treated girls was despicable. Lorna was sure that he and William had a bet that Craig could charm, kiss, and dump every girl in their class before graduation, and she’d long ago decided he damn well wasn’t going to do it to her. Uggghh! Craig! So perhaps William might not have been such a bad option after all.

“Well?” Iris repeated.

“I’m not sure I can go, actually.” Lorna scrambled for an excuse. “It’s getting close to the start of lambing, you know, so I doubt Dad would let me go.”

“Well, don’t tell him then,” said Iris. “Just tell him you’re going to be doing homework with me. He can’t say no to that.”

“I thought you were suddenly all moral these days, the influence of the church’s favorite son on your soul, and all that,” Lorna replied. “And now you are telling me to lie to my father?”

“Not lie exactly. Just not tell him the whole truth,” said Iris. “That’s not the same thing at all.”

“Yes, it is, and you know it!” Lorna tried to sound lighthearted, but panic was setting in. “Honestly, Dad can’t spare me.”

“But you said yesterday that lambing won’t start for another week or so. And anyway, he’s got Nellie to help him, and the German.”

“No, Iris, I really can’t.”

“It’s Craig, isn’t it?” Iris said. “You don’t want to go out with Craig. But why? He’s gorgeous.”

Lorna pulled a face. “If you like that kind of thing, I suppose.”

“Don’t be like that, Lorna. Craig is actually very nice. And you’re lucky he’ll even bother, because I know he’s been flirting with Esther Bell for ages.”

“Craig and Esther? That’s not an image I’ll get out of my head anytime soon.”

“But Craig is such a good friend to William that he says he will go with you even so,” Iris pressed on, ignoring Lorna’s snide comments.

“Well, that’s flattering!”

“But you have to, Lorna!”

“Why do I have to, Iris?” snapped Lorna.

Iris suddenly smiled her most angelic smile and pulled Lorna into a tight hug.

“Because if you don’t go too, I can’t go,” she said. “Mum wants you to act as chaperone to me and William.”

“Iris!” Lorna was trapped, but only for a second. “Why don’t you ask Esther Bell to go with you then, if she fancies Craig so much?”

“I don’t want to go to the dance with Esther Bell!”

“You won’t be going with Esther Bell.” Lorna imitated Iris’s dramatic tone. “You’ll be going with William Urquhart. And Craig Buchanan will be going with Esther Bell. And everyone will be happy—especially Esther. When was the last time anyone asked her out?”

“That might work, I suppose,” conceded Iris, “but I still wish you’d come with us.”

“I told you. Lambing. My dad. And also the fact that I wouldn’t touch the Adonis that is Craig Buchanan with a fifty-foot barge pole, even if I was paid to stab him to death with it!”

Lorna laughed, and soon Iris joined in, albeit sulkily.

Even though it wasn’t yet five o’clock, the sun was already low and the temperature was dropping fast.

“We’d better get back while there’s still some light,” Lorna said, pulling her gloves from her pocket. “But let me skim one more stone first.”

Lorna scanned the path around her feet, though it was getting harder to see now the sun had all but disappeared. There was a perfectly flat oval pebble a few inches from her shoe, and she picked it up with chilled fingertips, turning it to catch what light was left. It was the most beautiful blue-gray granite, with dark flecks that sparked even in the low light. It seemed a familiar color somehow. It reminded her of something, but of what, she wasn’t sure.

Instead of tossing it into the burn, Lorna left the pebble in her palm as she wiggled her hands into her gloves.

“Never mind, I’m done,” she said to Iris. “We need to get a move on anyway.”

“You’re not throwing that one?” Iris asked.

Already walking away, Lorna could feel the granite grow warmer against her palm, as it nestled between wool and skin.

“No, I think I’ll keep this one.”

Five (#ulink_613b30d6-be78-5f99-a16a-8d4e5720c47f)

Craigielaw Farm, Aberlady

Wednesday, 28 February

Dear John Jo,

Sorry it’s taken me a few days to write to you again, but I hope you are doing well and that it’s not as cold wherever you are as it is here.

Everything is fine. Mrs. Mack told me to send you her love and said that as soon as she’s finished knitting this last sock, she’ll get all of them wrapped up and sent to you in the hope that the parcel will reach you sometime before summer comes! If you are very lucky, you might get one of the fruitcakes she made the other day (not that there’s much actual fruit in it, or sugar, but she still gets it to taste good all the same!).

Iris and I are knitting scarves for Red Cross—shall I send you one of our marvelous creations? I’m not as good a knitter as Iris, you won’t be surprised to hear, but you’ll have to put up with one of mine since Iris has another neck to wrap hers around now. Yes, your greatest admirer is now madly in love with William Urquhart, of all people. (I know, disgusting!) She might have adored you her whole life, but now you’re out and William is in. Bad luck!

Are there any pretty girls where you are? (Where is that? I wish you could tell me!) If anyone can find one, I’m sure you can!

Dad is fine, but it’s almost lambing and there’s always too much to do. The Ministry of Agriculture sent us a new farmhand to take over from Old Lachie. Dad says the new man isn’t afraid of hard work and seems to know what he is doing, but the only thing is

I know you won’t like this, but

I can’t tell you how angry I was when

Lorna put her pen down on the blotting paper. How could she tell her brother that a German was working at Craigielaw?

But did she have to? Surely Dad would have already told both John Jo and Sandy the news in one of the letters he wrote to each of them every Sunday. They were never long letters, and Lorna doubted that he ever told them how much he missed them and wished he had them home again like she did, but two letters were sitting on the table every Monday morning without fail, ready for Derek Milne, the mailman, to pick up.

She lifted her pen, but put it down again immediately. She really wanted to be the one to tell her brothers about the prisoner, so they would know how angry she had been—how angry she still was—at the idea, so that they knew she was standing up for them, and so they would write back to her that they were angry about it as well. Then perhaps they would write to Dad and tell him he had to get rid of the German immediately.

But then again, perhaps they would feel reassured to know that their dad had a replacement for Lachie on the farm. And perhaps that also felt reassuring to Lorna. Perhaps the extra help would be … well, helpful.

So maybe she should say nothing. Yes, that was probably the best idea.

And anyway, how could she find the words to describe the way the burn had tightened the skin on that side of the prisoner’s face, the way that she’d noticed that no beard grew through the scar tissue, but that the blond stubble that grew on the undamaged cheek was so fine as to be almost invisible. Or about the way his smile tugged at the pink scar and how it made his gray eyes sparkle …

Lorna jumped as Nellie banged open the door from the yard, shattering the evening’s peace. She grabbed the unfinished letter and stuffed it into her pocket, as if she’d been caught writing something naughty.

But Nellie didn’t even come in. She just called through the open door.

“Can’t come in, love, muddy shoes, but is there any chance of another cup of tea? Your dad says the first ewe’s about to drop, and it looks like she’s going to need a bit of help. He says a cuppa would be spot on for us lot who could be up the rest of the night.”

“Of course, I’ll bring it over in a minute.”

“Cheers, m’dears!” Nellie called back as she pulled the door closed.

Once the tea was made, Lorna placed the steaming mugs onto a tray and put on her coat and rubber boots. Outside, she balanced the tray on her hip, as she pulled the door closed carefully behind her to make sure no light escaped. The blackout restrictions they had lived with since the beginning of the war had been lifted across the country a few months earlier, except for those who lived in towns and villages on the coast like Aberlady, in case of an attack from air or sea.

Caddy and Canny were slumped outside the door. They both sat up as she made her way across the moonlit yard, tails wagging, but they made none of the fuss they had made over the German.

They were both traitors.

Inside the lambing shed, Lorna found her father kneeling by a ewe lying on the straw, rubbing her belly. This wasn’t good. Sheep usually gave birth standing up, so this ewe must be exhausted by a difficult labor. Sure enough, every so often the animal would bleat pathetically.

Nellie was also kneeling, but at the tail end of the ewe. She looked disheveled but excited.

“Everything all right?” Lorna asked quietly as she laid the tea tray on the top of a wooden barrel just inside the door and rested a hand on Nellie’s shoulder.

“Aye, it’s her first time, but she’s doing fine,” Lorna’s dad said, without looking up.

“Yes, I’m all right, really,” said Nellie with a nervous smile.

“I was talking about the ewe,” said Lorna’s father with a sigh.

“Oh, right,” said Nellie. “Sorry.”

Her father palpated the ewe’s distended belly again with gentle hands.

“Almost there,” he said to Nellie. “Are you ready?”

At that moment, the ewe gave one agonizing bleat and a huge purple bag of semitransparent slop burst from her rear end. With a sickening squelch, the membrane burst. As the waters gushed out, Lorna could see the nose and front feet of the lamb for the first time. She waited for movement, but the lamb lay still on the damp straw.

“C’mon, girl!” Lorna’s father urged Nellie. “Get a move on and get the lamb out of there. Use that towel to give it a rub. You need to get it breathing and then give it to its mother quick as you can.”

But Nellie was still staring at the messy bundle that had almost landed in her lap, the color draining from her face.

“What are you doing,” Lorna’s father asked, “sitting there as if tomorrow would do? C’mon, girl, look lively!”

But still Nellie didn’t move; her eyes were glued to the thing in front of her. Then she simply tipped over to one side in a dead faint.

“Oh, for crying out loud!” muttered Lorna’s dad.

Lorna jumped to help. She pulled the towel from Nellie’s inert fingers, leaving her where she was, and laid it across her own lap. Using the towel, she eased the sticky membrane off the lamb’s nose and mouth. Then she rubbed its chest vigorously as if she were kneading life into a rag doll. The ewe lifted her head to see what was going on behind her and gave out another pitiful bleat. Lorna had done this many times before, but it didn’t get any easier, and frustration prickled in her throat.

“Come on, come on,” she implored the lamb. “You’ve got to breathe for me, wee man.”

Suddenly one of the legs jerked, then another, and a tiny shudder rippled through the lamb’s body. Lorna stopped rubbing and put her hand flat onto its chest. Yes! She could feel a fluttering; the lamb’s heart was beating. Then a cough, a breath, and a wriggle, and suddenly Lorna was struggling to keep ahold of the lamb as it strained to get to its feet. Relief flooded through her and a tear escaped her lashes and dropped with a splash onto the lamb’s sticky coat.

“Well done, lassie.” Dad’s voice was soft now. “Now, give him to his mother so he can get cleaned off and have a suckle. And then you can see to your other patient.” He nodded toward Nellie, who was lying with her face on the straw, as if she were asleep. “Even if she can fix a tractor and milk a cow, it’ll be a pain in the arse if she can’t stay upright for a birthing.”

Lorna waited for him to chuckle, but he never did. Looking up at her father’s face, she saw only exhaustion. As he moved down to the next pen to check on the ewe in there, he muttered, “Something else I’ll have to do myself.”

“But I can help you, and we’ve got the German during the day,” Lorna said, realizing again that his presence at Craigielaw was perhaps not so awful after all.

Once the lamb was suckling hard, safe in the care of its mother, Lorna went over to the windowsill, where there was a pile of freshly washed rags. She dipped one of them in a bucket of chilled water and returned to Nellie’s side.

Squeezing the cold rag slightly, she wiped it across Nellie’s face.

“Wake up, Nellie,” she said. “It’s all over and there’s a cup of tea for you. Come on and look at the wee lamb.”

Six (#ulink_22f97352-2818-554a-a8f0-68811981f861)

Lambing season was officially upon them. The next day, when Lorna got home from school, she headed over to the lambing shed in search of her father, but instead found the German prisoner. He was sitting on the straw with his back against the wall, watching as a ewe nudged her newborn lamb to its feet. From where Lorna stood by the door, she would never have known there was any damage to his face at all, and in that light and at that angle, she was reminded of her dream where she’d seen his face as it might have been. Handsome.

Remembering how upset he’d been the last time they’d talked, and suddenly embarrassed that he might catch her staring, Lorna backed out of the shed before he could even realize she was there.

Over the next few days, more than a dozen lambs were born with no danger to either lamb or ewe. But there were a couple that needed help with the birth, and both those ewes had pushed their lambs away, which meant they’d need to be fed by hand.

Mrs. Mack told Lorna that Paul had barely left the lambing shed each day. She was determined not to appear over-interested in him, but Lorna went to the lambing shed to offer help anyway. But Paul refused, saying he was fine. His manner was curt and efficient. Though Lorna knew she had said the wrong thing to him, she didn’t feel she needed to give an actual apology. It wasn’t like his feelings should matter to her or anything.

It was a relief just to know that the flock was well cared for during the daytime. The nights, however, were taking their toll on Lorna’s father. Lorna hadn’t seen him look so tired since he had been juggling days working on the farm with regular night patrols with the East Lothian Home Guard. Thankfully, those duties had ended before Christmas when the Home Guard had been stood down, but still, Lorna hated seeing her dad looking so weary.

One evening after tea, he announced that he’d written to the camp commander at Gosford, and Paul had been given permission to stay overnight at the farm, at least during the lambing season. Hearing this news, Nellie widened her eyes at Lorna in the mirror as she applied another layer of bright red lipstick in preparation for her evening off down in the village.

“So now shall we start locking our bedroom doors then, duckie?” she asked. “But then again, perhaps not!”

She gave Lorna a sly wink and danced out of the door before Lorna could respond.

Not that she knew how to respond. Would it make any difference at all to her if Paul was on the farm overnight? No, of course not, no difference at all. None.

The following morning, Lorna helped her father bring the old canvas camp bed down from the attic. They put it, with a pile of sheets and blankets, into the hayloft above the barn, where Paul would be sleeping until lambing was over.

It then fell to Lorna to take Paul’s evening meals to him. That first night she found him sweeping the floor of one of the pens in the lambing shed with the big hard-bristled yard broom. He greeted Lorna politely, and she felt another pang of … not guilt exactly, but … well, she knew she ought to clear the air.

Lorna set the dishes down on the barrel by the door and watched Paul work. After a few seconds, he looked up.

“About what I said”—Lorna’s throat caught on the words and she had to cough to clear it—“when you first arrived …”

Paul didn’t reply, and she could read nothing in his face.

“I didn’t mean to … at least, I didn’t think …” Lorna couldn’t find the right path at all. “I didn’t mean to upset you.”

“But you don’t want me here, me or the other Germans.”

“Well, no, I mean, yes, oh …”

Paul stood up straight and sighed.

“Fräulein Anderson, do you think that we like being here?”

It hadn’t occurred to Lorna that these men might be as angry about being in Scotland as the people they met there. He must have seen the confusion on her face, and he softened. “But thank you for”—Paul seemed to be searching for the right English—“your words.”

He went back to his sweeping.

Not sure what else to say or do, Lorna returned to the house. The conversation hadn’t solved anything, but she was glad she’d said something.

Later, when she went back out to pick up his dishes, she found Paul sitting on the straw in one of the pens with his back against the wall, feeding a lamb with a bottle. Another lamb was curled up asleep beside him.

As Lorna pulled the door closed quickly behind her so no light escaped, he looked up at her, and this time he smiled.

“Forgive me, I cannot stand up,” he said, lifting the lamb slightly as if to show he had his hands full. “But thank you for dinner. It was very delicious.”

“Tea,” Lorna corrected. “We have dinner at midday, in Scotland anyway, so we call this your tea.”

“I will try to remember that, thank you.”

As she cleared the plate, bowl, and empty milk bottle into her basket, Lorna became aware that Paul was still watching her.

“Sometimes,” he said, “you make me think of Lilli.”

Against her better judgment, Lorna asked, “Lilli?”

“My sister,” he replied. “She will become sixteen in May, and she is not shy to say what she thinks. Like you, Fräulein.”

Lorna wasn’t sure how to react. It unnerved her to be compared to someone he loved. But she was also intrigued that he too had left a little sister at home, as her brothers had.

So would it hurt just to ask one question?

“Is Lilli your only sister?” she asked.

Now his expression did change, she could see that even in spite of the burns. But did he look pleased that she had responded? Or relieved? She wasn’t sure.

“Yes, we are two,” he replied, “with our father and mother. Or we were. Before. Now it is only Lilli and Mother and me.”

“So your father …?”

Paul looked down at his hands and picked at a dirty hangnail on his thumb, and Lorna wished she’d kept her mouth shut. He took a deep breath.

“My father was ein Uhrmacher, a clockmaker, before the war. In Dresden.” He suddenly looked up at Lorna. “You know of Dresden, Fräulein Anderson?”

Lorna shook her head no, but then, perhaps she had heard something about Dresden quite recently. But where? At school? No, she didn’t think so. Perhaps a news report on the BBC?

“Dresden is very beautiful, very old,” Paul continued. “The River Elbe goes through the city, and there are many churches and art galleries. And parks, many parks. But you know, life in Germany has been difficult for some time, even before the war began. We had little to eat, and what food my mother could find was expensive to buy. And there was much to fear. But before that, I can remember a time when life was better. When my life was good.”