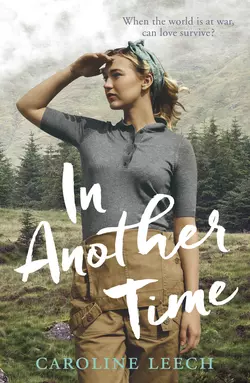

In Another Time

Caroline Leech

A captivating World War II romance from the author of WAIT FOR ME, perfect for fans of CODE NAME VERITY and SALT TO THE SEA.It’s 1942, and Maisie McCall is in the Scottish Highlands doing her bit for the war effort in the Women’s Timber Corps.As Maisie works felling trees alongside the enigmatic John Lindsay, Maisie can’t help but feel like their friendship has the spark of something more to it. And yet every time she gets close to him, John pulls away. It’s not until Maisie rescues John from a terrible logging accident that he begins to open up to her about the truth of his past, and the pain he’s been hiding.Suddenly everything is more complicated than Maisie expected. And as she helps John to untangle his shattered history, she must decide if she’s willing to risk her heart to help heal his. But in a world devastated by war, love might be the only thing left that can begin to heal what’s broken.

First published in the USA by HarperTeen,

an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Inc. in 2018

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2018

Published in this ebook edition in 2018

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins website address is

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Text copyright © Caroline Leech 2018

Cover © Harper Collins Children’s Books 2018

Cover design by Aurora Parlagreco

Cover art by RekhaArcangel/Arcangel (girl) and Rixipix/Getty Images (background)

Typography by Aurora Parlagreco

Caroline Leech asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008249151

Ebook Edition © July 2018 ISBN: 9780008249168

Version: 2018-07-24

To the lumberjills who served in the Women’s Timber Corps in the forests of Scotland 1942–1946

To Perryn, Jemma, Kirsty, and Rory

You are my everything

Epigraph (#uf4c16416-af20-5352-bd4f-fc18d5686157)

John Anderson, my jo, John,

We clamb the hill thegither,

And mony a canty day, John,

We’ve had wi ane anither;

Now we maun totter down, John,

But hand in hand we’ll go,

And sleep thegither at the foot,

John Anderson, my jo.

from “John Anderson, My Jo”

ROBERT BURNS, 1759–1796

Contents

Cover (#u8a8b2637-57c4-589a-9d0a-f488962ba1c3)

Title Page (#udb36f93f-6591-545a-95ae-addb58824d6d)

Copyright (#u4454a963-298b-51b0-bc14-a64014871f23)

Dedication (#u9e0c2e18-807b-5b61-8699-f1dbe2113cf1)

Epigraph

Chapter One (#u17e2d82e-2212-5286-880a-931a97cf2015)

Chapter Two (#u9058635b-4554-5fda-961c-93d8c01e937a)

Chapter Three (#ud2aad6e9-65ef-59d0-bafd-9c8f8bac7b4f)

Chapter Four (#u720d456f-7349-5a40-8e36-131a93b2a325)

Chapter Five (#u30e25234-459f-5685-acb4-cc483f9ed118)

Chapter Six (#u4aefaec8-6c62-5c10-b5b0-8072d5769d4d)

Chapter Seven (#uabe7b686-ae77-5518-ab98-316c01b82655)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

Books by Caroline Leech

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

(#ulink_5f0fab60-98d0-5ef1-8e43-4e443a6bc597)

WOMEN’S TIMBER CORPS TRAINING CENTER,

SHANDFORD LODGE, BRECHIN, ANGUS

FRIDAY, AUGUST 14

, 1942

Maisie’s shoulders burned, her palms were torn, and her ax handle was smeared with blister pus and blood. Again.

The woods were airless today, and it made the work even harder than usual. As a bead of sweat ran down from Maisie’s hair toward her eye, she stopped to wipe her forehead with the sleeve of her blouse, knowing she’d probably just added yet another muddy streak to those already across her face. Maisie wondered how on earth she’d be able to get herself looking presentable enough to go to a dance by seven o’clock. She’d only be dancing with her friends, but still, she didn’t want it to look like she’d spent the week up to her knees in dirt and wood chippings. Which, of course, she had.

Perhaps it was just as well there was no chance that some handsome chap would ask her to dance. She would bet a week’s wages—all thirty-seven shillings of it—that there were none of them left in Brechin these days, not since every man aged between eighteen and forty had been called up to the war.

Maisie stood and stretched out her back, pretending to study the tree she was attempting to chop down. When would this constant ache disappear? Even after two weeks of learning how to fell, split, saw, and sned, she still woke up each morning feeling like she’d gone ten rounds in the ring with a heavyweight champion. She had blisters on her hands from the tools—four-and-a-half-pound axes, six-pound axes, crosscut saws, hauling chains, and cant hooks—and blisters on her feet from her work boots. There were even blisters between her thighs where the rough material of her uniform chafed as she worked.

“I bet the WAAF and ATS recruits don’t hurt this badly all through their training,” she moaned to her friend Dot, who was working two trees over. “I still think the recruitment officer lied to me. She made it sound like the Women’s Timber Corps would be a walk in the park.”

“Or perhaps a walk”—Dot flailed her ax again toward the foot of her own tree—“in the forest.”

“Very funny,” Maisie replied, then blew gingerly onto her stinging fingers. “Bloody hell, that hurts!” She pulled out her once-white handkerchief and dabbed at her hands, hoping to feel some comfort from the soft, cool cotton, and watched Dot swing the ax a couple more times. Again and again Dot’s blade seemed to bounce off the wood as if it were made of India rubber, exposing no more of the creamy flesh under the brown bark than had been visible five minutes before.

Maisie glanced behind her to see if their instructor, Mr. McRobbie, was watching, but he was talking to another recruit farther up the line of trees, so she let her ax-head rest on the ground. She had been issued this six-pound ax when training began, but right now, it felt like a forty-pound sledgehammer. She reached into her pocket and withdrew her whetstone, the smooth flat stone she used to set her blade. Mr. McRobbie had drummed into them the importance of having a whetstone with them at all times, to keep the cutting edge sharp and clean, but Maisie had discovered another use for it. She laid the stone, warm from her body heat, onto the blisters of her hands one by one, sighing as the discomfort was eased, if only for a few seconds.

Still Dot was hacking away at the tree.

Maisie sighed. “Do you want me to finish that off for you? We’ve got a dance to go to tonight, remember, and the way you’re going, you’ll still be slapping at it at midnight.”

“Uggghhh,” grunted Dot with one more swipe. “What am I doing wrong? I feel like I’m doing it the way he showed us, and I’ve got blisters a mile deep to prove it, but I don’t ever make any difference at all! Bloody thing!”

Dot kicked the toe of her boot at the trunk and there was an ominous creaking sound, as if the tree were about to topple. Dot recoiled and jumped clear, but the tree stayed where it was.

Maisie burst out laughing. “Perhaps you should kick the tree into submission.”

“Oh, get lost!” Dot retorted, but then she began to laugh too. “I only want to find one thing on this training course that I can actually do properly, because cutting down trees certainly isn’t it.”

Maisie felt sorry for Dot. She was shorter and slighter than Maisie, though certainly not the smallest of the women in their group, yet Dot couldn’t seem to get the hang of any of the techniques Mr. McRobbie had shown them. After only two weeks, Maisie already felt quite competent at using the tools they had been given so far, but Dot was not progressing at all. That fact was not only making Dot anxious, it was starting to worry Maisie too. They were only two weeks into their six-week training course, but it had been made clear that anyone could be sent home at any time for failing to make the grade. She couldn’t bear it if her new friend were thrown off the course. Who would Maisie have to talk with and work beside then?

The other women doing the Timber Corps training were all very nice, but that was the problem—they were all women, in their twenties and thirties. Only Dot was close to Maisie in age, and even then, Dot was already nineteen, almost two years older than Maisie. But it was comforting to have a friend of roughly her own age, someone who treated her like a teammate rather than a child.

Maisie had certainly felt like an adult last month when she’d walked into the recruiting office in Glasgow and told the sergeant behind the desk that she wanted to join the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, or even the Auxiliary Territorial Service. She was all ready to argue with him that since she was a grown woman taking control of her life, she didn’t need to finish her final year at school because it was about time she did her bit for the war effort.

But the sergeant hadn’t argued with her. He’d instead pointed her to the next office, where a friendly woman told her with a smile that, at seventeen, she was still too young to become a WAAF or a Navy Wren, or even to join the ATS.

Imagining the smug expression on her father’s face as she returned home with her mature and independent tail firmly between her legs, Maisie tried not to whine. “So is there nothing I can do instead?”

“There’s the Women’s Land Army,” the woman replied. “They take Land Girls from seventeen, if you’d fancy working on a farm. It’s hard work, but if you like the outdoor life …”

Maisie could rather see herself walking through fields of golden corn swaying gently in the summer breeze, chewing lazily on a stalk of barley as the sun warmed her skin.

“… you’d be working with crops and with the animals. You know, cows, horses, pigs, chickens, and the like …”

Cows? Horses? Pigs?

A shudder ran down Maisie’s aching back even now, remembering that conversation. She might enjoy working with chickens or maybe sheep, but not big animals like cows and horses. She especially hated—no, she feared—horses, ever since the rag-and-bone man’s Charlie, a brutish Clydesdale, had taken a swing at Maisie with his huge head and left a nasty dark-red graze and a blooming bruise on her arm with his enormous teeth. How old would she have been? Eight perhaps? It still made her feel queasy.

“No, not animals. I can’t do animals.”

The woman had frowned at her.

“Well, I’m not sure there’s much else other than munitions, dear,” she’d said, “and a bright and healthy girl like you doesn’t want to be stuck in a factory all day, surely. Oh, wait now, here’s something …”

She’d rummaged around in a drawer and pulled out a single sheet of paper. “This is quite a new setup, but according to this, they’re taking girls from seventeen into the new Women’s Timber Corps. It says here that because of the German sea blockade, supply ships can’t get through to bring timber to Britain. Therefore, we need to get the wood from our own forests. Of course, all our foresters are soldiers now, so they’ve created this, the WTC. How does that sound?”

When Maisie didn’t immediately respond, the recruiter had continued. “Would trees be more your thing, dear?”

Trees? Trees certainly didn’t have teeth. “Yes, thank you,” Maisie had said, “that sounds spot on. I think trees might be much more my thing.”

From somewhere nearby, a whistle blew three times, long and loud. Miss Cradditch, the WTC training officer at Shandford Lodge—known as Old Crabby to all the recruits—had a particularly piercing and insistent whistle, but right now no one cared since it signaled the end of the workday. Next stop, the Brechin dance.

As Maisie walked with Dot and the others down to the Hut C dormitory to gather her towel and soap, she knew she’d made the right decision at the recruiting office. After only two weeks on the course, Maisie was already proud to be training as a lumberjill.

Maisie stared down into the brown-speckled bathwater with distaste. The luxury of the long, deep baths she’d enjoyed at home before the war seemed so long ago now, since all she was allowed to bathe in these days were her strictly rationed five inches of water. And with so many women in the camp, and only three proper bathrooms upstairs in Shandford Lodge, the old manor house that had been converted into the WTC training center, there had to be a roster for who bathed when. It had been four days since Maisie’s last turn to have a bath, and since those days had all been hard physical work, half of the Shandford woods appeared to have made its way into the bath with her.

The water, which barely covered her legs, wasn’t even warm, but it was wet and soothing, and she felt herself relax immediately. After all, she was one of the lucky ones, having her bath on the same day as they went dancing, so she slid as much of her body down into the water as she could, while also trying to keep her hair dry. She considered her hands, not sure if she should risk putting open sores into such filthy water, but how else was she going to soap the rest of her body? Throwing hygienic caution to the wind, she picked up her small, pink WTC-issued bar of carbolic soap, just as someone banged on the bathroom door.

“Come on, Maisie, don’t take all night.” Dot’s voice was muffled by the thick wood. “The truck’s leaving in less than an hour. You need to hurry! Do you even know what you’re wearing yet?”

So much for that long luxurious bath!

“All right,” Maisie shouted back, quickly rubbing the soap up to a stinging lather between her hands. “I’ll be down in a few minutes, and maybe you can help me decide.”

Once she finished her bath, Maisie ran down to Hut C to get ready. She had only brought two dresses from home, so it wouldn’t be hard to decide on an outfit. Many of the other women had worked the whole day with curlers under their decidedly nonregulation head scarves, but thankfully, Maisie only needed to brush out her shoulder-length blond hair and pin it up at each side. Dot’s short dark hair was even quicker, just combed and tucked behind her ears, so the two of them were ready with time to spare.

As they waited for the truck to arrive, Maisie and Dot watched the older women fuss with whatever face powder, mascara, and lipstick they had saved from before the war—it was almost impossible to get hold of any makeup these days, especially in the wilds of Scotland. All Maisie had done was smear a little Vaseline on her lips to give them a shine. She’d only be dancing with the other lumberjills, so what was the point?

Even so, Maisie was excited to be going out. Two weeks after leaving home for her new adventure, tonight felt almost like a rite of passage.

(#ulink_9593192c-59de-516f-8f66-0b252ba708d0)

Brechin Town Hall, where the dance was being held, was a dour place, with dark marble columns and heavily ornate carvings on the walls and ceiling. To make things worse, the blackout blinds were already in place over the tall windows, meaning that none of the summer evening light would filter into the hall. The dance organizers had done their best to cheer things up by bringing in some spotlights and hanging some brightly colored banners from the gallery above the dance floor, so Maisie wasn’t complaining. They were lucky to be allowed out from camp for any dance at all.

When the WTC girls had arrived, the band was already playing on a raised platform at the far end of the hall, and after a couple of numbers, Maisie had decided that the musicians were rather good. Brechin was a small town in the middle of nowhere, after all, not a metropolis like Glasgow. She was soon having fun, dancing either with Dot or with Mary, a red-haired girl from Aberdeen, and before long, Maisie noticed that her aches and pains had eased significantly.

Maisie couldn’t help but notice that some of the other lumberjills were moaning about the lack of men to dance with. But what had they expected? With the war on, there were only a few locals left to go dancing, and they were only old men and young boys. Some of the boys were near Maisie’s age, strutting around with gangly arrogance, even though it was clear they were not yet old enough to be called up, but Maisie studiously avoided making eye contact with any of them. She was quite happy to dance with her new girl friends. No pressure, no need to explain, they could just have fun.

However, not long before the end of the dance, the atmosphere suddenly changed, and heads began turning to look toward the front doors. Maisie was dancing again with Mary, and the two of them were forced to stand on tiptoe to see what was happening. Who had arrived, and why was it causing such a fuss?

Maisie strained to see over the other girls to the front, where more than a dozen men were standing inside the main door, nicely dressed, in suits and ties, each in turn handing his hat to the elderly cloakroom attendant, who was suddenly standing straighter and smiling wider than before, now that there were some handsome men in the room.

All right, not many of them were handsome, but even so …

A ripple of whispered excitement washed around the room as the first of the men reached the edge of the dance floor. “Americans, Americans, Americans …”

Maisie tugged at Mary’s arm. “Come on—let’s keep going. I like this tune too much not to dance to it.”

All through the rest of that number, however, Mary kept glancing over her shoulder.

“They’re Americans, though, Maisie!” she hissed, and then giggled. “Look, look! That one’s asked Lillian to dance. And that tall blond girl from Hut B has nabbed one too. Oh my goodness, they’re not wasting any time, are they?”

Mary was now so distracted that they were virtually at a standstill again, and Maisie found herself getting quite annoyed, though she wasn’t sure if it was with Mary or the men.

“It’s quite rude, really, turning up so late, don’t you think?” Maisie grumbled. “There’s only a dance or two left.”

Clearly Mary didn’t agree. She grabbed Maisie’s hand and pulled her over to a table at the edge of the dance floor. “Then there’s only a chance or two left to land a dance with one of them!” she declared, and leaned casually against a chair, pushing her chest out and pouting more than a little.

Maisie could feel the blush rising in her own cheeks at this blatant show of … of what, she didn’t know, but she didn’t much like it. She grabbed her handbag from the nearby table where she’d left it and headed for the ladies’ to comb her hair, cool her face, and sulk a little. Her whole evening had been spoiled, thanks to those men.

Once she’d collected herself, Maisie realized she was actually feeling quite anxious. But that was ridiculous—it was only a bunch of men, for goodness’ sake, even if they were Americans.

Back at the table, there was no sign of Mary. Maisie’s neck was aching again, so she bent her head forward, pulling her shoulders down and back, to stretch out the muscles. As she did, she became aware of someone hovering nearby and, without lifting her head, she glanced sideways along the floor until she found a pair of polished black leather shoes sticking out from dark tweed trousers with wide cuffs.

“Go on!” she heard an American man say. “She won’t bite, you know.”

A woman giggled at his comment.

The shoes suddenly moved toward Maisie, a hopping, stumbling approach, as if their wearer had been shoved from behind. Maisie jumped back in alarm, whipping her head up to see who was about to crash into her.

The man attached to the shoes managed to catch his balance by grabbing onto the chair beside Maisie just before he bumped into her. Beyond him was a blond man, grinning widely, with one of the other WTC girls—Maisie didn’t know her name—hanging on his arm.

The shoe man looked mortified, a frown furrowing deep lines across his tanned forehead.

“My apologies,” he said, his voice deeper than Maisie had expected, “I didn’t mean to scare you. But some people seem incapable of minding their own business.”

He glared over his shoulder, but the blond man only laughed and pulled the woman toward the dance floor. When Maisie didn’t immediately reply, the shoe man coughed to clear his throat.

“My friend thinks that I should ask you to dance, since there can’t be many more numbers left before it ends.”

Maisie said nothing. What could she say? Certainly, it would be nice to dance for once with someone who was taller that she was, someone who didn’t expect her to lead the whole time as Dot and Mary did. But she’d prefer him to ask her to dance because he wanted to, not because his friend told him to.

“I mean …” He looked embarrassed now. “It’s not that I don’t want to ask you to dance, it’s just … oh hell! Pardon me! What I mean is … well, I don’t dance.”

Maisie’s humiliation grew with each word.

“Well, why did you come then?” she asked, sounding snippier than she’d meant to. “It’s a dance. What else did you think you would be doing?”

As she turned away, wishing the ground would swallow her up, fingers closed around the top of her arm, not tightly, but with enough pressure to stop her.

“Look, I’m sorry.” He sounded like he meant it, so she turned to face him again. “We got ourselves off on the … er, wrong foot, so to speak, which is a shame.”

He dropped his grip on her arm and shrugged apologetically. There was an earnest expression in his dark-brown eyes, now that she really looked at him, and the skin around them was like soft leather, tanned and supple, but with tiny wrinkles, as if he squinted into the sun too often. Or as if he were always smiling. Except he wasn’t smiling now, he was grimacing. At her.

“And while I don’t usually ask women to dance,” he began again, “we’ve found ourselves into this rather embarrassing situation now, so perhaps I should make the effort. If you’d like me to, that is.”

Though Maisie heard the words, she was wondering how an American like him could have ended up on a Friday evening in August in Brechin, of all places, and why he …

“Miss?” He was frowning again. “Would you like me to?”

Maisie startled. “Sorry. Pardon me? Yes! Erm, no, erm, sorry?”

His expression shifted into wry amusement at her embarrassment.

“I asked whether you would mind if I were to ask you to dance?”

In her blushing confusion, Maisie took a moment or two to work her way through the question.

“I think so?” she said. Was that the right answer? “Or …”

Then he smiled, and sure enough, the soft skin around his eyes wrinkled up in tiny folds. It was unnervingly infectious and Maisie couldn’t help but smile back.

“You think you would mind?” He was clearly teasing her now. “Or you think I should ask you to dance?”

Maisie gave him an exaggerated sigh. “Is every question you ask this complicated, or is this how all Americans talk?”

“Not every question, no. But sometimes, it can be more fun this way.” He held out his hand toward her.

Maisie hesitated. It might not have been the most romantic invitation, but it seemed like a genuine one after all that. And maybe this might be fun.

“Thank you,” she said, laying her hand onto his. “I’d very much like to dance.”

Her heart sped up as they walked the few steps to the dance floor and waited for a space to allow them to enter the dance. But then she noticed that his fingers were moving strangely against her own, and Maisie’s delight quickly evaporated. She’d forgotten about her blisters, and could only imagine how unpleasant they must feel against his palm. Before she could pull her hand back out of his, however, he lifted it up and studied it, frowning again, as if trying to work out a puzzle. Maisie realized with a sinking feeling that he was trying to work out why a young woman would have the callused hands of an old crone, disgustingly rough, with hard-crusted blisters and sharp-edged cuts and cracks. Embarrassment again flooded through her and she snatched her hand from his grasp, tucking both her hands around her waist to hide them from his scrutiny.

“They’re awful, I know,” she burst out. “But it’s the work, the tools. They rip up our hands, and there’s nothing we can do to protect them. It’s vile, I know.”

“Tools?” he asked.

“Axes and saws, in the woods. I’m with the Women’s Timber Corps.” Despite her embarrassment, Maisie lifted her chin defiantly, already anticipating the same derision she had received from her father. “I’m training to be a lumberjill.”

“A lumberjill, eh? Hmmm.” He seemed to be suppressing a smile, and Maisie felt her hackles rise. Why did men find that so ridiculous?

But instead of sneering, he took one of her hands back, resting it flat on his, and let his thumb rub gently across her palm and up her index finger, hesitating briefly by each blister, just disconcertingly long enough for her to feel the warmth from his touch.

“I mean, they issued us with gloves,” she blurted out, “but they’re all too big, so when you’re using an ax, it feels like your hands are slipping on the—”

“Pig fat,” he said.

What had he said? It sounded like pig fat to Maisie, but that was too bizarre, even for an American.

“Pardon?”

“You need pig fat and Vaseline,” he said again, smiling now.

“I have no idea what you’re talking about.”

“Rub your hands with a mixture of pig fat and Vaseline morning and night, and this shouldn’t happen anymore.”

“But …” Maisie wasn’t sure what to say. “But how would you know …?”

Slowly he turned over his free hand and held it out flat next to hers. Even in the low light, Maisie could see that he had once had blisters in almost all the same places as she had on her own hands—on all three pads of each finger, the two on the thumb, as well as across the bridge and the heel of the palm. His weren’t fresh and crisp and sore as hers were, but there was a distinct whitening of hard skin in each place, the pale shadows of blisters where calluses lay as a permanent reminder of pain in his past. His scars matched hers.

He turned his hand over so it again lay palm to palm on Maisie’s. A sudden wave of relief caught her by surprise. He understood and he wasn’t repulsed.

“But how did your hands get like that?” she asked.

“You’re not the only one who knows how to swing an ax,” he replied with a wink.

The band had begun a new song. Maisie recognized the tune, but in the confusion of having her hand held by a stranger, she couldn’t place it right then. He seemed to know it, though, because he glanced up at the band and grinned, squeezing her hand between his.

“Perhaps we can talk about my magic blister potion later, but while the band is still playing this lovely song, maybe we ought to dance?”

“Thank you. I’d like that”—Maisie let herself smile a little too—“and I’m Maisie, by the way.”

“I’m glad to meet you, Maisie. My name’s John Lindsay.”

It became very clear, very quickly, that John Lindsay was a dreadful dancer.

When he had first guided Maisie into the crowd of slowly spinning couples, she’d enjoyed the reassurance of having his warm hand on her back. And once she had swallowed down the embarrassment of having this tall and rather handsome man holding her so close, Maisie almost relaxed. But then they’d stumbled, bumping into two other couples, and Maisie had had to fight to keep herself from falling. Whether it was because she’d lost her balance when she lifted her eyes to look up into his for a moment, or whether he’d simply tripped over his own feet, she wasn’t sure, but either way, this was not how she had hoped her first dance as an independent woman would go.

As John tried again to swoop Maisie around the dance floor, she couldn’t escape the feeling that she was risking life and limb, his larger frame and extra weight always pulling her off-balance. This was fast becoming a nightmare. How could a young and obviously fit man be so completely incapable of dancing?

She risked another glance up at his face, expecting him to be smiling apologetically, but there was no smile. In fact, it was as if the earlier sunshine had been smothered by the darkest of storm clouds. He was frowning, as if concentrating hard, and his breath came heavily now. Then she noticed that he seemed to be swallowing again and again. Was he unwell or in pain? Or was he drunk? She hadn’t smelled any beer or whisky on him, but even so …

Suddenly, John took Maisie by the elbow and walked her to the side of the dance floor, where he let her go and staggered against the nearest chair, appearing to have difficulty catching his breath. Then, barely glancing up, he held out his hand, palm toward Maisie, as if trying to keep her away.

“I can’t do this. I’m sorry, Maisie. I really can’t.”

“What’s wrong?” Maisie wasn’t sure whether to be embarrassed or annoyed. “Can I get you some water maybe?”

John didn’t reply but turned and walked unsteadily toward the front entrance. Hesitating only long enough to proffer his cloakroom ticket and grab his hat from the attendant, John disappeared out of the door.

What the hell had that been about? He might not have been much of a dancer, and he certainly wasn’t much of a gentleman either, but even so.

Maisie glanced around to see if anyone else had noticed her untimely abandonment, but everyone seemed to be paying attention only to their dance partners or to the friends they were gossiping with.

Luckily for Maisie, that had been the final number, and as soon as it ended, everyone clapped and the band began to pack up for the night. All the dancers made their way back to their tables, with much laughing and promises of more dances next time, and gradually they all crowded out the stained-glass front doors and into the mild evening.

Out on the street, however, it was clear that what had happened hadn’t gone unnoticed by the other lumberjills after all, and Maisie found herself subjected to an inquisition from Dot and Mary. All the way back to the waiting truck, they demanded details.

“What did he do to you?”

“Nothing.”

“Then, what did you do to him?”

“I don’t know.”

“Did he step on your foot?”

“No.”

“Did you tread on his foot?”

“I don’t know.”

“Was he really as bad a dancer as it looked?”

“I don’t know! Actually, yes. Yes, he really was. Simply terrible,” Maisie said sadly, which caused much merriment for her friends.

“Talk about having two left feet!” chuckled Dot.

“You certainly pulled the short straw,” added Mary. “Such a shame—he was good-looking too.”

Even as they teased her, simply knowing that her friends were as indignant as she was that her partner had walked away like that made Maisie feel a little better.

On the drive home to the lodge, Dot and Mary delightedly shared with the other recruits the story of Maisie, the American, and their disastrous dance. At first, it was quite funny, even to Maisie, but as more and more of the women joined in, offering ever more hilarious comments at John Lindsay’s expense, Maisie found herself becoming defensive. He didn’t deserve this treatment. He’d been nice enough before they’d started dancing, even funny, and he was handsome, and until he had walked out on her, he’d been scrupulously polite and had shown such concern about her hands. It was only when they started dancing that he became … odd. Even so, he didn’t deserve ridicule from people who hadn’t even seen what had happened.

“Stop it!” she burst out. “Stop saying things like that.”

After a moment’s silence, somebody started a teasing “woo-hoo,” and soon everyone was joining in, making jokes about Maisie having found herself an eligible bachelor at last, Maisie being in love, Maisie and John sitting in a tree.

Maisie put her head down and tried to ignore them. She knew they were only having fun, still riding their own wave of excitement from the dance, but still, she could do without a second, no, a third bout of humiliation in one night.

Only Dot, sitting next to Maisie, was not joining in the ribaldry and teasing. She nudged Maisie and laid her head on Maisie’s shoulder, as the other women’s conversation moved on to discuss their own dance partners instead of Maisie’s.

“It’s all right,” Dot said so only Maisie could hear. “If he was thoughtless enough to walk away from a lovely girl like you, then it was his loss, not yours.”

Maisie nodded, but couldn’t force any words in reply past the knot that was tightening in her throat. Why had she let herself start to think that perhaps he might like her? And she might like him back?

But Dot was right. Walking away from her had been his loss.

(#ulink_3c5b44dc-410e-5d55-8d76-3e022a52f4cd)

Maisie awoke with a start. A drum! Some blighter was beating a bloody drum inside their hut, and on the morning after a late night too!

The usual routine of being woken up at dawn by Old Crabby’s incessant whistle blowing from outside the dormitory was bad enough, but being dragged from deep sleep after a dance by an apparent crash of drums from inside the hut was a hundred times worse.

And now there was shouting too.

“Come on, ladies of Hut C, up you get! Sooner you’re up, the sooner it’s over.”

Maisie was still trying to cling to the last threads of a dream about dancing in the strong arms of a dark-haired man.

“What time is it, for goodness’ sake?” Dot croaked from the next bed over, and Maisie’s dream dancing was done.

“No idea,” replied Maisie, lifting her head blearily from the pillow and squinting toward the far end of the hut, where she saw Phyllis Cartwright, the tallest, strongest, and most athletic of all the WTC recruits, striding along, banging on the end of each bedstead with a stick. So, no drums, after all, just Phyllis with a bloody thunderstorm on a stick. “But whatever time it is, Phyllis has clearly taken leave of her senses.”

“We’ve all had enough of these aches and pains,” Phyllis bellowed, “so from now on, we’ll start each day with some calisthenic exercises to warm up the muscles and get us all ready to work.”

Maisie dropped back onto her pillow with a loud groan.

“But why today? We didn’t get to bed until after midnight.”

“None of that now, Maisie.” Phyllis was standing over her now. “This was your idea, after all.”

The groaning spread quickly around the room.

“My idea?” Maisie protested. “I didn’t ask for this.”

“Yes, you did, Maisie. Yesterday, you said to me how everyone was still aching, and how hard Dorothy here was finding the physical work each day because of her weak muscle tone.”

“You said I was weak?” Dot glared at Maisie. “I’m not weak.”

“No, of course I didn’t say you were weak,” Maisie said quickly, “I only said that you’d never done this kind of intensive physical activity before, you know, because you didn’t play sports at school. That’s what you told me the other day, that your school didn’t even have hockey or tennis or anything.”

“No, I didn’t have much tennis during my childhood,” replied Dot, and Maisie caught a very un-Dot-like bitterness in her voice. “But that doesn’t mean that I’m—”

“Dot! Honestly, I didn’t tell anyone that you’re weak. This is just Phyllis—”

“This is just Phyllis doing her job,” Phyllis interrupted, striding off around the room again, banging on any bed with an occupant still buried under the blankets. “I’m making sure you are all given the chance to develop your strength now, so that you won’t struggle with the heavier stuff later, once you are out in a real camp, taking down real trees. I’m a fully trained physical fitness instructor, remember—five years teaching at Morrison’s Academy in Crieff, then another six at the Edinburgh Ladies’ College—so don’t go thinking I’m only a pretty face.”

Phyllis gave one of her wide rumbling belly laughs, and most of the women in the hut joined in. Phyllis’s face would never be described as pretty—handsome, yes, even striking, but not pretty—but that was something she seemed quite proud of.

Phyllis’s enthusiasm was infectious, because despite the early hour, soon everyone from Hut C was standing in uneven ranks on the wide expanse of driveway outside Shandford Lodge, stretching and jumping, bending and running on the spot.

Women from some of the other huts must have been disturbed by the rumpus, because they appeared up the hill in ones and twos to see what was going on, and some even joined in.

Finally, after half an hour that felt to Maisie like a week, Phyllis took pity on them and released them to get breakfast.

To Phyllis’s credit, the atmosphere in the dining hall was far livelier and more engaged than it had been any morning so far. The women were chatting and laughing, and some were singing along to music from the wireless in the corner. Again, Maisie realized that the exercise, like the dancing, had warmed her muscles to the point where she wasn’t even feeling the aches and strains that had been her constant companion since training began. Now, if she could just work out where to find some pig fat for her hands …

Just then Old Crabby appeared at the door, interrupting the merriment, her very presence demanding silence. She held up a wide, flat basket, tipping it forward for everyone to see.

“Postcards!” she shouted in a voice more suited to an army drill square than a dining hall. “If any of you want to do your family duty, may I remind you that recruits’ mail will be picked up and taken to the post promptly every Saturday morning at nine o’clock. So if you want to write a postcard home, do it now, ladies. They’re already stamped, which will cost you tuppence.”

She slammed the box down onto the nearest table and picked up an old tobacco tin with a slot cut in the lid. “Honesty box is here for the tuppences. Of course, if you are literate enough to write a proper letter home, you can come now to my office. Letter stamps are tuppence ha’penny.”

As Miss Cradditch turned smartly and left the room, there was a scramble of hands trying to grab one of the postcards and a stubby little pencil from the basket, and a tinkle of coins dropping into the tin. Several women got up and followed Old Crabby out of the door, each holding at least two or three thick envelopes.

Maisie stared at the basket, wondering if today was the day she should write a postcard home to her parents. She’d sent no word back since she’d walked out of the front door of the home she’d lived in for all seventeen years of her life, her father’s hurtful words still ringing around the tiled hallway. She wasn’t even sure they would know which part of Scotland she was doing her training in. All the letters from the WTC had been addressed to her by name, and since her parents had been so furious with her for signing up, they’d refused even to look at the information she had been sent. It was only at the last minute, as Maisie was standing in the front hall with her suitcase, that her mother had softened, if only marginally. She’d come out of the kitchen holding a brown paper bag, which she held out to Maisie.

“Here’s a sandwich for the journey. It’s only fish paste, but that’s all there is. And I’ve given you an apple and your ration of cheese for this week. You can get a cup of tea at the station.”

Maisie had taken the bag with a tight-throated thank-you and had stepped forward in the hope that her mother might embrace her, but her mother stayed where she was.

“Will you at least walk me to the bus stop?” Maisie had asked.

“The fact that you’ve chosen to leave home before you’ve even finished your schooling”—her mother hit the well-worn track without hesitation—“suggests you have no desire to spend any more time with us than you must.”

“Mother, please let’s not do this again.” Maisie had tried not to sigh. “I’d like it very much if you’d all walk with me to the bus stop. Thank you.”

Maisie’s sister, Beth, had been the only one who had seemed in the slightest bit excited for Maisie. Perhaps she was already envisaging her own escape from their parents—she was almost sixteen, after all. As if to prove her support, Beth had already had her shoes on and had been grabbing her coat from the hall stand.

“Shall I get your coat too, Mother?” Beth had asked.

Father’s voice from the dining room had not been loud, but it had been crystal clear. “Your mother will not be needing her coat. And neither will you, Elizabeth.”

“But, Dad,” Beth had begun, “what if there’s rain?”

“Put. The coats. Away.” Maisie’s father’s tone had been unmistakable, a command that was to be followed without question. But as she always did, Beth had pushed back.

“But surely—”

“Elizabeth! Your sister has decided she is mature enough to ignore the wishes of her parents and sign herself up for some ridiculous venture with women who clearly have no more sense than she does. She must therefore be mature enough to get herself there alone, so put the coats away, and go help your mother in the kitchen.”

Suddenly he had been at the dining room door, and without even glancing in Maisie’s direction, he’d stalked past his daughters and his wife to his study door. There he’d stopped, his fingers on the brass knob.

“I will not repeat myself again, Elizabeth. Your sister can see herself out. You have breakfast dishes to wash.”

So Maisie had walked to the bus stop alone, and she had not written home since.

Maisie sighed as she looked at the basket of cards. She knew she ought to send something, at least to Beth. It hadn’t been Beth’s fault their parents had reacted so badly, but even so, that morning might have been the first time in years that quarrelsome and complaining Beth had ever supported Maisie in an argument. With two and a half years separating the girls, arguments had been routine, and it was usually Beth who started them.

No, Maisie did not even want to write to Beth.

Now feeling grumpy, Maisie picked up the plates and cups in front of her and Dot, and cleared them onto the pile of dirty dishes stacked on the serving counter. Dot’s nose was still buried in a book, as it was most mornings over breakfast, and all the other women around her were scribbling on their cards. Dot didn’t ever send mail home either, Maisie had noticed, though the one time she’d mentioned it, Dot had evaded her question and quickly changed the subject. Since Maisie had no desire to share details of the misery of her own home life either, she’d let the matter drop.

A sharp stab of pain and a spurt of warm pus across her palm made Maisie realize that she’d been distractedly digging her thumbnail into one of the large blisters on her left hand. Hoping no one else had noticed, she dabbed at her palm with the corner of her handkerchief. She ought to wash her hands, but she was sure that the harsh carbolic soap was partly to blame for her blisters since it dried out her skin, which was already in trouble from its first exposure to an outdoor life. So if she wanted to avoid washing her hands so much, what she needed was …

Maisie changed course and sidled a little nervously toward the kitchen. Old Crabby had made it clear on the first day that Mrs. McRobbie’s culinary domain was not to be entered without invitation. Mrs. McRobbie was the cook for Shandford Lodge, and was married to the old woodsman, Mr. McRobbie, who had been their primary instructor for all the ax and saw cuts, and also for tool care. He also had an encyclopedic mind when it came to all things flora and fauna in the woods around the lodge, something that Maisie had already found useful when faced with a patch of stinging nettles or if one needed to know, as Helen had the week before, whether the snake wrapping itself around one’s boot was a venomous adder or a benign grass snake. Although Mr. McRobbie tried to be gruff and miserable with them, no one was convinced by the act. His wife’s reputation, however, was truly fearsome, and so Maisie knocked gingerly on the doorframe before her toes had even crossed the kitchen threshold.

“Mrs. McRobbie?” she called tentatively.

There was a rustling and shuffling from beyond the pantry door, and the cook appeared, her tiny frame dwarfed by the enormous sack of flour she was carrying.

“Oh, here, let me help,” said Maisie as she dashed forward and wrestled the sack out of Mrs. McRobbie’s arms. “Where shall I put it for you?”

The cook pointed over to the far counter and Maisie laid the flour down. Hoping this favor might make Mrs. McRobbie more open to a request of help, Maisie quickly asked her question. “Do you have any spare pig fat I could have?”

The older woman gazed at her for a moment. “Pig fat?” she replied. “You mean lard?”

“Oh, well, if lard is pig fat, then yes, lard. Please, if you have some to spare. I have money.”

“Show me,” said Mrs. McRobbie, putting out her hand.

Maisie dug her sore hand gingerly into her pocket to find some coins, uncertain of how much pig fat might cost.

“Not your money, girl! Show me your hands.”

Maisie could see now that the cook wasn’t asking for payment but was holding out her hand, palm up, as John Lindsay had done. Self-consciously, Maisie laid her own hand on top as Mrs. McRobbie leaned forward, clicking her tongue and shaking her head.

“You’re in a wee bit of a mess there, aren’t you? But I’m sure I can find you some lard, if that’s what you think’ll work.”

“That’s what I was told would work,” Maisie said, following the cook into the pantry, “by one of the American chaps we met at the dance last night. He said I should mix it with some Vaseline and smear it on the blisters.”

“An American, was it?” said the cook, as she drew back a white muslin cloth and cut into the large oblong of white fat it covered. “I didn’t know that there were any Americans around here. Were they not the Canadians?”

“Canadians?”

Mrs. McRobbie had retrieved a crumpled sheet of brown paper and was folding it around the white block. “Aye, there’s a whole bunch of Canadian lumberjacks up the road a piece, working on the old laird’s estate, clearing it for another army camp, from what I heard.”

“Oh, I’m not sure,” Maisie said, “maybe.”

She remembered that Mary had said that they were Americans, but had John said that himself? Perhaps not. And then it occurred to Maisie that she hadn’t even bothered to press him further on what he’d been doing to get blisters that matched hers, or about where he was from. In fact, she hadn’t asked him anything about himself at all. Her mother would not be pleased if she knew that, because according to her, a lady should always use the eighty–twenty rule when talking to a gentleman.

“Men like to talk only about themselves,” Mother had said. “Therefore, a lady must ensure that eighty percent of the conversation should be by him or about him, and she should only ever talk about herself as an answer to his direct question, making sure to turn the conversation back the other way as quickly as possible.”

Maisie had snickered with Beth through this lecture, but now, remembering that all that she and John had talked about was her wish to dance and her hands, she was left to wonder if that was why John had abandoned her.

Damn! She hated to think her mother might be right.

Mrs. McRobbie was watching her, and Maisie realized she was waiting for an answer to some question that Maisie hadn’t even heard.

“Sorry?”

“I asked if the chap holding your hands at the dance was handsome.” The old woman’s eyes were sparkling with amusement. “You know, the Canadian.”

“He wasn’t Canadian, I don’t think. And he wasn’t at all handsome.” Maisie tried hard not to blush under the cook’s scrutiny. “Well, yes, he was quite handsome, but he wasn’t holding my hands, other than to dance, obviously, since you have to hold hands to dance, but he wasn’t holding them, not like that.”

“Like what, dear?”

“Like that, like you mean, I mean,” Maisie could feel herself getting flustered.

Mrs. McRobbie’s smile spread wider. “Oh well, there’s time yet.”

As if realizing that Maisie was becoming anxious, the cook suddenly shoved the block of lard into Maisie’s hand. “Off you go now—the others will be waiting for you, I’m sure.”

“Oh, right. Yes. Thank you.” Maisie waved the lard in the air, and as she turned back toward the dining room, Mrs. McRobbie chuckled again.

“And best not put that on your hands just before you pick up an ax, dear. I don’t want Mr. McRobbie being decapitated. He’s to fix the tiles on our roof before the end of the summer, and he’ll need a head for that.”

Maisie smiled as she went back to the dining room. So much for the fearsome Mrs. McRobbie.

Dot, Phyllis, Mary, and Anna had already left the dining room by the time Maisie caught up with them.

“We wondered where you’d gone,” said Dot. “Come on, back to the axes. According to Phyllis, Mr. McRobbie thinks we can move on to snedding tomorrow if we conquer chopping today.”

“Lucky us!” said Mary.

As they passed the office, several girls were still waiting to get stamps for their letters. Beside them, on the table by the office door, was the basket of postcards, enticingly blank, other than the scarlet stamp bearing King George’s head in the top right corner.

Maisie hesitated. Even if she put her money into the honesty box and took a postcard, it didn’t mean she had to send it. Not today, anyway. She could keep it to send for Beth’s birthday perhaps. Or even for Christmas. She didn’t have to send it right now.

But then, why waste tuppence on it now if she wasn’t going to send it till later? That made no sense.

Then it came to her. She would make a deal with herself. If she had exactly the coins to pay for the stamp, she’d get the postcard. If she didn’t, she’d walk away.

Digging her hand into her trouser pocket, Maisie pulled out the small collection of coins and counted them off with one finger. Two shillings, five ha’pennies, and three farthings.

“Damn!”

She did have the right change to make two pennies exactly. With a resigned sigh, she slid four ha’pennies into the honesty box and picked up one of the cards, waggling it in her fingers for a minute or two before stuffing it into her back pocket.

No, she would not send the postcard today, but at least she knew she had it, just in case.

(#ulink_194dde20-4daa-5cd6-9554-8b5b46264c9b)

Later that morning, Maisie and the others followed Mr. McRobbie for their final chopping lesson through the paths of the estate to where the old woods butted up to a wide stretch of pine plantation. Here the trees stood like soldiers on a parade ground, set at regular intervals, in rows and columns, each about five yards away from its neighbor. Maisie was pleased to see that here there was almost no underbrush or scrubby grass below the trees to get in the way of her ax, only a carpet of fragrant brown needles.

On Mr. McRobbie’s order, the lumberjills all lined up along the first row of sturdy trees, one girl to each trunk, and set to work to chop it down. Although she was gradually figuring it out, chopping hadn’t turned out to be as easy as Maisie had expected. But it was early days, she kept telling herself, because by the end of the course, she would know how to chop and saw, how to fell a tree, how to clear all the small branches off it—that was snedding—and also how to roll the logs using their cant hooks, and then haul the timber away with hooks and chains. They were also learning the uses for the different woods, and how to cut to a specific measurement. The trees the girls were chopping today were Scots pine, so they would probably end up sawn to short lengths as pit props for coal mines, or perhaps as fence posts, with the wastage going for charcoal. But for any of that to happen, the lumberjills had to get the trees down first.

“Don’t swing so wildly, lassie!” Maisie heard Mr. McRobbie shout at someone farther down the line. “You’ve to let it sing. Hear the music in your head, and let it flow through your arm and into your blade. I told you that yesterday. Have you still not found yourself a chopping song yet?”

Maisie was relieved Mr. McRobbie had started at the other end of the line, because she hadn’t found her chopping song yet either. Mr. McRobbie had been telling the girls for days now to find a song with good rhythm that helped them to time their ax swings. But Maisie was struggling to come up with a tune that worked. Nearby, Lillian had clearly found hers. She was humming a short musical phrase over and over as she lifted her ax away from the tree, one, raised it high on two, rounded it over above her shoulder on three, and brought it slicing down into the wood on four. Perfection, exactly like Mr. McRobbie had shown them last week. The motion was smooth and controlled, and Lillian’s tree trunk was growing narrower at the waist with every cut.

“That’s it, lass, you’re doing a grand job,” said Mr. McRobbie as he spotted Lillian’s easy action. “Now get those cuts down as close to the ground as you can, so we don’t waste that bottom foot of wood, not while there’s a war on.”

He stepped back a little and raised his voice to address the whole group.

“So, there’s a bunch of Canadians”—Maisie stopped to listen, ax above her head—“working up the road right now, and do you know how they’ve been cutting down the trees over there?” Mr. McRobbie glared around him. “At knee height! And even, some of them I saw, at waist height. I couldn’t believe how much they were wasting, so I went to have a wee word with them and I put a stop to it.”

Canadians. Up the road. Not Americans then.

Lillian began to hum and swing again, and Maisie groaned in frustration. When he’d demonstrated what he meant by a chopping song, Mr. McRobbie had sung an off-tune “Auld Lang Syne” as he’d swung again and again in rhythm to the music, but when Maisie had tried the same tune, it didn’t fit her action at all.

“Find some music that means something to you,” he’d exclaimed passionately to the assembled recruits, “a song that flows from your breath to your ax, to your blade, to the tree.” The old man had looked like he could have started to dance with his ax, right there, and a few of the girls had mocked him quietly from behind.

And yet, his strange method seemed to work. Each day more and more recruits were swinging and chopping like professionals, and now the clearing was a cacophony of harmony and counterpoint, half-hummed dance tunes from Anna and Mary, and a medley of fully sung operatic arias from Phyllis. Everyone seemed to be singing except for Dot and Maisie.

As Maisie wondered about borrowing a tune from Phyllis, a thought popped into her head.

What song would John Lindsay hum as he was swinging his ax? Suddenly a tune came into her mind. It was the one she and John had danced to, albeit briefly and disastrously, last night, and it had been playing on the wireless in the dining room this morning too. What was it called? She could hear the tune quite clearly now, though she couldn’t recall all the words.

Keep smiling through, just like you always do,

Something blue skies something something far away.

It was one of Vera Lynn’s songs, she was sure … “We’ll Meet Again,” that was it!

Before the music escaped her mind, Maisie lifted her ax and weighed it in her hands for a second or two. Then, as she began to sing the opening words of the song under her breath—“We’ll meet again, don’t know where, don’t know when”—she hefted the ax away, curved it up and around behind her head, and brought it down sharp into the bark of the log.

Amazingly, it did the trick, and the blade cut cleanly through the bark. She kept singing quietly to herself, and although her movements were not exactly effortless, they were certainly more synchronized, as if she and the ax were suddenly one effective machine, not two engines pulling against each other.

Maisie let out a cry of delight as the ax bit sliced cleanly again into the flesh of the tree.

“You’ve found it at last, have you?” Mr. McRobbie laughed as he approached, though he stayed a safe distance from Maisie’s swing arc. “I knew you’d get it soon enough. And what about you, Miss Thompson?”

A grunt of effort, a thick slap of metal hitting wood, and a groan of frustration came from behind Maisie, as Dot failed yet again to make even so much as a dent in her tree.

“Well, lass, you maybe haven’t found quite the right song yet,” said Mr. McRobbie as he walked away. “But keep on trying.”

“Grrrrrrr!”

Dot was holding her ax handle as if she wanted to throttle the life out of it.

“Did you just growl at your ax?” Maisie snorted.

“It’s so bloody frustrating!” Dot cried. “How am I the only one who can’t do this?”

“Oh, come on, you’re not that bad.”

Dot pointed at Maisie’s log, and then held out her hand to her own, the surface of which could best be described as a little scuffed.

Dot suddenly lifted her ax up high over her head—not the way they’d been taught at all—and brought it down hard on the tree in fury. The impact ripped the handle from Dot’s grasp, spinning it straight at Maisie, who hopped to the side just in time. The ax buried itself in the ground close to where Maisie had been standing.

“Be careful!” she cried, but seeing Dot’s torn face, she felt more sympathy than anger. “Remember to treat your ax ‘as if it were your first-born bairnie, with love and with care.’” Maisie was mimicking their instructor’s strong Angus accent so well that Dot eventually gave a wry smile.

“Sorry, Maisie. But I’m serious. I’m so rubbish at this, they’re going to send me home.”

“Oh, nonsense. They will not. We’ve got plenty of training yet before we get posted to a camp to do this for real, which is more than enough time to sort you out.” Maisie put an arm around Dot’s shoulders. “Anyway, you and I have our first lesson this afternoon, and I’m sure you’ll be much better at that than me.”

“Well, I’ll have to be,” replied Dot, “or you’ll be looking for another friend by the end of the month.”

Driving, however, proved just as elusive to Dot as swinging an ax. That afternoon, Maisie found herself pitched violently around in the back of an old Morris car as Dot did her best to coax it along. But just as Dot got it going, the engine’s roar spluttered and died into judgmental silence. Dot smacked her hand onto the steering wheel and muttered “damn it” under her breath over and over.

Mr. Taylor had come up from his garage in Brechin to teach the recruits, two by two. He sat next to Dot with his hands on his knees, arms braced, as if he expected the car to take off again. Then he slowly exhaled, making his bushy black mustache flutter.

“Perhaps your pal should do the drive back, eh?”

Dot slumped forward in despair. “Why can’t I get anything right?”

“It’s fine, Dot, really.” Maisie reached forward to lay her hand onto Dot’s back. “Driving’s a complicated thing to learn. I’m sure Mr. Taylor took ages to learn to drive too, didn’t you, Mr. Taylor?”

The instructor turned to stare at Maisie with indignation, but eventually said, “Aye, well, maybe not quite as many problems, but I suppose it took a wee while.”

Maisie flashed him a grateful smile. “See? So don’t be down. It’s really not easy, you know.”

“But you took to it like the proverbial duck!” exclaimed Dot. “You only stalled the engine twice, and you certainly didn’t almost put us in a ditch like I did.”

“You didn’t put us in a ditch, Dot—”

“Almost in a ditch, I said,”

“No, not even almost in a ditch.” Maisie was trying not to smile. “We were still a good three feet from the actual ditch. Well, perhaps two feet. All right, we were six inches away …”

There was a peculiar snuffling noise and Maisie realized that Mr. Taylor was chuckling, and though she didn’t want to hurt Dot’s feelings, it was hard not to join in. But then Dot began to giggle as she clambered out and opened the back door for Maisie.

“Get in the front then, Flash,” Dot said, as she and Maisie swapped places, “and show me how it’s done.”

Maisie settled herself into the driver’s seat and grasped the steering wheel again, careful not to bump her blisters. Thinking hard about everything Mr. Taylor had told her, about the steering and gear changes, she started the engine and moved the car forward. Thankfully it didn’t stall, but after twenty yards, the engine began to whine and Mr. Taylor tapped his knuckle against the gear stick. “Come on, lassie, you can’t stay in first gear all the way.”

“Oh, right, yes, sorry,” said Maisie, pushing down on the clutch and wrestling the gear stick into second as the car continued up the lane toward the lodge, and then into third.

“That’s it, lassie, you’ve got it now,” said Mr. Taylor, “which makes one of you anyway.”

“I’m not sure I’ve really ‘got it,’” said Maisie with a proud smile, “but with a little more practice, I might. Will we see you again tomorrow?”

“No, that’s your instruction finished,” said Mr. Taylor. “Miss Cradditch says you’ve got a lot to learn in a short time, so this is all you’ll get from me.”

Maisie braked a little too hard and the car slammed to a halt in front of the lodge. “But we’ve only had one afternoon’s instruction. And on a car, not a truck.”

“If you can drive a car, you can drive a truck,” he said. “It’s all just a matter of scale, after all.”

“Scale?” Maisie could not believe what she was hearing. “A three-ton Bedford truck is not the same size as this car.”

Mr. Taylor gave another mustache-ruffling sigh. “As I said, it’s just a matter of scale. Now, don’t you fret, lass. It’s clear that you’re smart and strong, and if you concentrate, you’ll do just fine.”

Smart and strong? Those were two words she’d seldom ever heard used about her. Quite the opposite. For years, her father had been telling her she was weak willed, lazy, and stupid. And her mother always said that while Maisie was handsome enough—“handsome” was Mother’s word for Maisie; “pretty” was reserved for Beth—she’d have to shed some weight before she got too much older, if she wanted to marry. That was Maisie in her parents’ eyes, lazy and fat, certainly not smart or strong.

Maisie turned and offered Mr. Taylor her hand.

“Thank you,” she said, “I mean, for today’s lesson. I enjoyed it, though I’m not sure if I could ever do it—”

“I told you, you’ll do fine,” he replied, taking her hand in his meaty fist. Then he leaned closer and whispered, “But perhaps your friend ought to take the train or the bus instead.”

He gave Maisie a conspiratorial nudge and pulled a watch from his pocket. “I’d best be off. Mrs. Taylor will have my tea on the table at five o’clock sharp, and if I’m late, she’ll feed it to the dog.”

“If we get no more driving lessons,” moaned Maisie as she and Dot walked back to the hut, “I won’t have a clue how to do that again in a week’s time, let alone four weeks, when we get sent out to our new postings.”

“Well, as long as you remember enough by this Friday, you’ll be able to drive me to the station when they send me home,” Dot replied, misery clouding her usually bright voice.

Maisie nudged Dot’s elbow. “Come on, mopey. We’ve got first aid training on Monday, which’ll be interesting, won’t it?”

Dot looked unconvinced. “I fainted when we dissected a frog in school,” she groaned. “First sight of the blood, and I—” She mimed toppling over in a dead faint.

Maisie laughed.

“I’m serious,” Dot said. “I might as well pack my bags right now.”

“But first aid’s not all about mopping up blood,” countered Maisie, “or even bandages and slings. It’s helping people, and that’s what you’re best at, after all.”

Which was true. On their first day at Shandford Lodge, Dot had offered to help Maisie make up her bed with the stiff white sheets and thin gray blankets issued to them. By the time they had folded the corners in tight and smooth, and had helped some of the others too, Maisie already liked Dot very much. Dot had a genuine desire to get along with other people, though Maisie couldn’t quite work out why such a shy and slight girl would have volunteered for this very physical lumberjill life.

“I suppose,” replied Dot. “Just don’t send me any injured frogs!”

The following week, even before the end of their first aid training, Maisie could see that Dot was a gifted first-aider. The visiting tutor, a retired nurse from Dundee, recommended that Dot do additional training so she’d be fully certified. Since every camp was required to have someone with a first aid certificate, Dot was thrilled. It meant that not only would she stay a lumberjill, she’d also earn an extra shilling a week in her pay packet once she was out in the field.

Maisie was delighted for her friend too, and had to smile when she overheard Dot reassuring one of the other more squeamish recruits over breakfast the next day.

“Oh, don’t worry. First aid is more about helping people than it is about mopping up blood. I’m sure you’ll be absolutely fine.”

And suddenly it was the sixth and final week of training. This time next week, Maisie wouldn’t be a recruit, and she wouldn’t be at Shandford Lodge. She’d be a real lumberjill, working in a real camp, at last. The one thing, however, that dulled her excitement was knowing that she might be there alone. There was no guarantee that anyone from this group would be sent to the same place as Maisie, let alone a close friend like Dot, and they wouldn’t find out where they were all going until the postings were announced on Friday, the day before they all departed.

Maisie tried not to think about it, and hoped that the coming week’s sawmill training would distract her from the uncertainty of what was coming next.

On Monday morning as they trekked to Mitchell’s Sawmill in Tannadice, there had been nice breeze, but once they’d arrived it was clear that the cool air was certainly not finding its way inside the mill shed, even when the huge shed doors were propped open. It was hot, and it was loud.

Maisie stood with the others around an enormous bench saw and strained to hear the barked instructions from Betty Harp, who said proudly that she had been one of the very first WTC recruits, and would now teach them all her six months’ worth of sawmill wisdom.

“There are four rules you must follow in any sawmill,” Betty shouted. “One. No smoking. Cigarettes and sawdust are a bad combination.”

Everyone nodded.

“Two. No hair. Your hair must be tied back at all times. You do not want this little beauty”—she slapped her hand down inches away from the vicious whirling vertical blade of the saw—“to be your next hairdresser.

“Three. Gloves. Please wear your leather gloves at all times. But be careful—gloves can give you a false sense of security around these blades, and even thick leather is no competition for spinning steel, so you still need to be careful. And remember, you’ll never get to enjoy a manicure again if you have no fingers.”

Maisie winced and immediately pulled her work gloves out of her pockets.

“And four. Communication. By that, I don’t mean chatter and gossiping. In this mill, you are responsible not only for your own safety, but for the safety of all your team. If you tell them exactly what you are about to do before you do it, you’ll all stay safe. Got it?”

The girls all nodded their agreement and followed Betty to the first machine.

Over the next two hours, Maisie watched Betty closely as she taught the group to adjust and feed big tree trunks into the big table and routing saws, and showed them how to use the edger, the jointer, and the plane. After a tea break, they were split into pairs, and Maisie worked alongside Helen at one station, then another, until they reached the routing saw. They both stood baffled for several minutes, until Betty came and gave them instructions again.

Just as Helen finally managed to get the engine turning over, though, a sharp scream rose above the din, and then another. Maisie shouted to Helen to shut off the saw again, waiting only until the blade started slowing before she ran to see what had happened. The others were already grouped around the big headsaw, and even from the back, Maisie could hear Dot’s voice above all the others.

“Catherine! Press down hard on this, would you? Harder! Someone give me a belt. I need a tourniquet on her arm. And a cloth, I need another cloth. No, something cleaner than that. Your shirt’ll do. Come on, give me your shirt, we need to get it wrapped quickly.”

Maisie peered over the crowd. Lillian was lying flat on her back on the sawdust-covered floor, groaning and panting, her face ashen, her eyes squeezed tight shut. Dot crouched at her side, wrapping a bundle of green cloth around Lillian’s hand—Catherine’s blouse by the look of it—and as Maisie watched, the fabric slowly darkened as blood seeped through.

Betty shoved through the crowd, carrying a metal box painted with a red cross. Throwing open the lid, she grabbed a large paper packet and thrust it at Dot.

“Thanks, Betty,” said Dot, her voice strong and decisive, “but I can’t let up the pressure yet. Can you tighten the tourniquet around her upper arm to limit the blood flow first? And then carefully open that packet, but try not to touch the gauze as you hand it to me. I need to get the cut wrapped so it’s kept clean. I’m sure they’ll be able to stitch it up, but if the gash gets infected, then … well, let’s just keep it clean, all right?”

Lillian whimpered at Dot’s words, and Maisie tried to push past the people in front so she could give her some comfort. But Anna had already dropped to her knees and was laying her hand gently onto Lillian’s forehead while she whispered soft words of reassurance.

Maisie glanced up at the saw table behind Dot, where the circular saw sat innocently still. Its guilt was clear, however, from its red-smeared teeth. A few inches away, a tan leather work glove lay abandoned, empty fingers curled as if in supplication. It was just like the ones Maisie had on, except that this glove’s palm had been torn wide open—no, not torn, sliced. The cut across the smooth brown leather ran very neatly in a straight line from the bottom of the index finger to the heel. Its gaping edges were sharp, and were marred by dark-red staining of the pale leather all along their length. Someone beside her gagged, and Maisie realized that Lillian’s glove had been no match for the cold steel of the headsaw, exactly as Betty had warned.

Within thirty seconds, the tourniquet belt was tight and Dot was wrapping the injured hand in its fourth layer of bandage. And then the truck was there by the open door of the mill shed, and Phyllis, Mairi, Helen, and Maisie were lifting Lillian onto the flatbed at the back while Dot kept applying pressure on both the well-wrapped hand and the pulse point on Lillian’s wrist. As they laid her down, Maisie tried to reassure Lillian that everything would be fine, but the words felt hollow. After all, what did Maisie know about these things?

Once Lillian was settled, with her head lying in Anna’s lap and with Dot still at her side, the truck pulled away. As she watched it go, Maisie heard someone say, “Well, still waters run deep, don’t they? Who’d have thought mousy little Dorothy would step up and take over like that?”

“Just as well she did,” another voice replied. “I was close to fainting at all that blood.”

Maisie felt a rush of pride knowing she wasn’t the only one who’d noticed the transformation in Dot. She’d looked so confident and in charge, and Maisie knew that Dot had finally found her place as a lumberjill. But what about poor sweet Lillian? If the cut was as bad as it looked to Maisie, perhaps Lillian’s days in the Timber Corps had just come to a sudden and sorry end.

(#ulink_aeaabd4b-62ac-5218-afbc-baa96dc85fd3)

The next morning, Betty Harp brought them news of Lillian, who was apparently doing well. She had been transferred from the cottage hospital in Brechin to the much larger Dundee Royal Infirmary, where surgeons had operated on her hand overnight. Betty praised Dot’s quick thinking and determination, and told the group that because Dot had kept pressure on Lillian’s hand all through the journey to the hospital, the doctors were hopeful that Lillian would not lose the use of her fingers, though only time would tell.

Once the lumberjills had applauded this good news, Betty repeated her lecture about safety in the mill, about wearing their gloves at all times—“Lillian might have cut her hand, but she’s kept her fingers because she was wearing her gloves”—and about doing exactly what they were damn well told.

Once the lecture was over, all the girls gathered around Dot, patting her on the back and congratulating her. Dot tried to say it was nothing, that anyone else would have done the same, but Maisie could see that under the pink flush, Dot was thrilled.

And all through the rest of the week Dot was like a new person; rescuing Lillian had provided her the confidence to take on any number of tasks. And there were so many new things still to learn in the sawmill that even Maisie felt rather overwhelmed.

By Friday afternoon—the end not only of their sawmill training but of their Timber Corps training too—everyone was sick and tired of the work, as well as the stifling heat in the shed.

The unusually high temperature rather spoiled what should have been an exciting day. They had come to the end of their training at last, even if they were now looking at unknown futures. In fact, the weather was so unbelievably hot for September that at knocking-off time there were no cheers at all. Everyone just drifted wearily toward the track up to Shandford Lodge, wiping the dust and sweat off their faces and necks with scarves and handkerchiefs, not even bothering to congratulate each other for finishing the grueling training.

“Ladies!” Phyllis shouted from behind them, bringing them all to a stop. She was standing by the same Bedford truck that had carried Lillian to the hospital days before. “To mark this auspicious day, the end of our lumberjill training, we will be taking a little detour to do something we should have done days ago. Come on, up you get, and we’ll be on our way.”

With that, Phyllis pulled herself up into the driver’s seat and beeped the horn twice as the ignition roared.

Maisie looked around for the truck’s usual driver, a man named Eddie, but there was no sign of him. She clambered aboard the flatbed anyway, sitting down just as the truck lurched off toward the main road.

For the first time in hours—days even—Maisie felt cool, fresh air ruffle her sweaty hair and blouse. Was this what Phyllis had planned? A refreshing breeze for the trip home? But then Phyllis drove past their usual turnoff, and they were almost to Forfar before she suddenly swung the truck off the road and down a rutted dirt track. Maisie grunted involuntarily as she was thrown around with the other girls, bouncing on the hard truck floor every time Phyllis hit a bump. Fortunately, Phyllis soon slammed on the brakes, cut the engine, and jumped down from the cab.

“Follow me!” she cried, and was over a gate and off down a footpath beside a recently harvested field before anyone could ask her where they were going. Soon, Maisie was picking her way with Dot and the other lumberjills along the side of the barley stubble toward a wooded area at the far side of the field.

Maisie had long since given up trying to guess where they were being led when she heard excited cries followed by a splash. As she and Dot came through the thick curtain of young larches, an expanse of dark-blue water extended away from them. The sun dappled silver onto the surface, and ripples extended out across the long and slender loch. Suddenly, a naked Phyllis rose up from the surface, spraying water around her, and Maisie found herself clapping and laughing with delight.

“Come on in, everyone!” Phyllis cried through the sheet of water pouring over her face. “It’s glorious!” Then she turned away and, bending double, gave a neat surface dive back into the water, a move that brought her bare buttocks up to the surface for a split second before they vanished again, followed by her legs, with a neat scissors kick of her feet.

Catherine, Mairi, and Mary clearly needed no second invitation, because they were already tearing off their sweat-soaked uniforms and charging over the soft grass into the water. The older women, Cynthia, Anna, and Helen, were a little more genteel, folding their uniforms neatly on top of their boots before tiptoeing down to the edge and easing themselves into the water with gasps and giggles.

“This is fantastic!” Maisie cried to Dot, as she tried to undo both bootlaces at the same time. “Why did no one think of doing this before?”