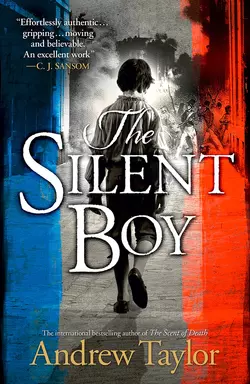

The Silent Boy

Andrew Taylor

From the No. 1 bestselling author of THE AMERICAN BOY comes a brilliant new historical thriller set during the French Revolution.Paris, 1792. Terror reigns as the city writhes in the grip of revolution. The streets run with blood as thousands lose their heads to the guillotine. Edward Savill, working in London as agent for a wealthy American, receives word that his estranged wife Augusta has been killed in France. She leaves behind ten-year-old Charles, who is brought to England to Charnwood Court, a house in the country leased by a group of émigré refugees.Savill is sent to retrieve the boy, though it proves easier to reach Charnwood than to leave. And only when Savill arrives there does he discover that Charles is mute. The boy has witnessed horrors beyond his years, but what terrible secret haunts him so deeply that he is unable to utter a word?

Copyright (#ulink_b52768bc-995d-5b4d-99f1-dfae8d6d021d)

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2014

Copyright © Andrew Taylor 2014

Cover design layout © HarperCollinsPublishers 2014

Cover photographs © Julian Elliott / Getty Images (street);

Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy (back); Henry Steadman (boy)

Andrew Taylor asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it, while at times based on historical fact, are the work of the author’s imagination.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007506576

Ebook Edition © AUGUST 2014 ISBN: 9780008132781

Version: 2017-05-10

Dedication (#ulink_681662f7-0d63-5494-b0e3-bf8a8ec69104)

For James

Table of Contents

Cover (#u1fcc982a-0da4-517e-9641-e7962a58c168)

Title Page (#u836ff8a3-6785-5a06-b3b1-79c17547d7c2)

Copyright (#u2c6b0206-81cc-5b6e-b486-a5e65f4ce523)

Dedication (#u3e1e8352-69a9-5b57-af01-7216bc1c5731)

Chapter One (#udfdb3f90-84f4-574d-9fae-ffcf99649d91)

Chapter Two (#u63867a6c-1475-5ae7-89f8-6b2003720f92)

Chapter Three (#ue495a896-013c-5b0b-b338-782ac6ffea63)

Chapter Four (#u6e2d3a83-d5ad-5135-b94b-5a979bf6e7c2)

Chapter Five (#u59e2f20a-4ac1-56aa-952e-41604bed9c87)

Chapter Six (#u12374db9-7b86-5814-b584-58c3942d1ed5)

Chapter Seven (#u61a7abc7-9f1f-54e1-8fb6-5fcbcac025c1)

Chapter Eight (#u1cf0150c-c603-5a12-8158-e9a90954b7fd)

Chapter Nine (#ua3e78a4c-11d7-522a-b381-a98060770dac)

Chapter Ten (#u06305dba-34c6-58ba-aba5-36c47cb0926c)

Chapter Eleven (#ubf6eb398-bdf0-544b-8490-0177c0daa1e1)

Chapter Twelve (#u1a9b0af6-2d6e-535f-b620-ee98768f6d38)

Chapter Thirteen (#u8652b5f2-c674-5824-96e7-8df43aa18356)

Chapter Fourteen (#u7d23219c-cf85-53be-b1ab-941b2d18d225)

Chapter Fifteen (#ub9cc83e6-ccba-5ab1-a5b0-28b26f5f583b)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Forty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

By the same author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#ulink_8a50e798-e779-5ed2-b356-a4a9807de39c)

Say nothing. Not a word to anyone. Whatever you see. Whatever you hear. Do you understand? Say nothing. Ever.

Tip-tap. Like cracking a walnut.

Now and always Charles sees the blood. It runs down his cheek and soaks into his shirt. He licks his dry lips and tastes it, salty and metallic and forbidden.

He has fallen as he ran down the steep stairs. He’s lying on his back. He looks up. It is raining blood from a black sky striped with yellow. Blood glistens in the light of the lantern on the table.

There’s shouting and banging outside.

Inside, the blood is crying out. It’s screaming and shouting and grunting. The sound twists through his skull. It cuts into bone and splinters into a thousand daggers that draw more blood.

He scrambles to his feet. His shoes are by the door. He slips his feet into them.

There are no words for this, all he has heard and seen. There are no words for anything. There must never be any words.

Awake and asleep, here and anywhere, now and always. Never any words.

Charles lifts the latch and drags open the heavy door. No more words.

Hush now. Say nothing.

Tip-tap.

Charles darts out of the cottage and pulls the door shut. The cobbled yard is in darkness. So are the workshops and the big house beyond. Above the rooftops, though, the air flickers orange and yellow with the light of torches. The noise is deafening. He wants to cover his ears.

The tocsin is ringing. There are other bells. Their jangling fills the night and mingles with the host of unnatural sounds. The street on the far side of the house is as noisy as by day – much noisier, with shouts and screams, with barks and explosions, with the clatter of hooves and the grating of iron-rimmed wheels.

Someone begins to knock at a door – not with a hand or a knocker. These blows are slow and purposeful. They make the air itself tremble. Glass shatters. Someone is shrieking.

Wood splinters. They are breaking down the door of the main house. In a matter of minutes they will be in the yard.

Charles stumbles towards the big gates beyond the cottage. Two heavy bars hold them shut, sealing the back of the yard. In one leaf is a little low wicket.

At night the wicket is secured by two bolts. He fumbles for them in the darkness, only to find that they are already open.

Of course they are.

He pushes the gate outward. Nothing happens. Locked, not bolted? In desperation he tugs it towards him. The gate slams into him with such force that he falls on the slippery cobbles.

The cottage door is opening.

Panic surges through him. He is on his feet again. The lane outside the gate is in darkness. He leaps through the wicket. The lane beyond runs parallel to the street. The warm air stinks of decay. The city is so hot it has gone mad.

In the confusion, he is dimly aware that the hammering from the house has stopped. There are lights on the other side of the yard. Shutters are flung open. The windows fill with the light of hell.

Chains rattle, bolts slide back. A dog is barking with deep, excited bellows.

Through the open wicket he sees the house door opening. He glimpses the black shape of a huge dog in the doorway.

Charles covers his mouth with his hand to keep the words inside from spilling out. He turns and runs.

There is so much confusion in the world that no one gives Charles a second glance. They push past him. They cuff him out of their way as if swatting a fly.

He is of no interest to them. He is nothing. He is glad to be nothing. He wants to be less than nothing.

He shrinks back into a doorway. He sees blood everywhere, in the gutters, on the faces and clothes of the men and women hurrying past him, daubed on the wall opposite.

At the corner of the street, the crowd has surrounded a coach. They are pulling out the man and the woman inside and throwing out their possessions. A hatbox falls open and the hat rolls out. A man stamps on it.

The woman is crying, great ragged sobs. The gentleman is quite silent. His eyes are closed.

The baker’s assistant, who is a burly fellow half a head taller than everyone else, tugs at the woman’s dress. He paws at the neck. The thin fabric rips.

Charles slips from the doorway. He does not know where he is going but his feet know the way. He has nothing with him except the shirt he was sleeping in, his breeches and the shoes on his feet.

The sign of the Golden Pheasant hangs above the shop that sells poultry. Someone has draped a petticoat over it.

Old Barbon, the porter of the house five doors down, is lying on the ground. He is pouring wine into his mouth and the liquid runs over his cheeks. Barbon once gave him a plum so sweet and juicy that Marie said it came from the angels.

Madame Pial, who keeps the wine shop in the next street, is dragging a sack along the road. She has lost her hat and her cap. Her grey hair flows in a greasy tide over her shoulders.

The Rue de Richelieu is seething with people. Their faces are twisted out of shape. They are no longer human. They are ghouls in a nightmare. Charles pushes through them in the direction of the river. The street ends at the Rue Saint-Honoré. He means to turn left and cross the river at the Pont Royal. But the crowd is even denser here, clustering around the Tuileries like wasps round a saucer of jam. He will not be able to force his way through.

Besides, lying on the road not three yards away from him is one of the King’s Swiss Guards. The man has no head and he has lost his boots and breeches. His entrails coil out of his belly, gleaming in the torchlight, still twitching.

Charles slows. He weaves eastwards towards the Île du Palais. He crosses the river at the Pont Neuf. National Guards are on both sides of the river and also on the Île du Palais itself. But they are taking no notice of the people who stream north over the river towards the Tuileries. He slips among them, against the flow of the tide. He smells sweat and excitement and anger.

There are fewer people on the Rive Gauche. But the noise is almost as bad. The sound of artillery and musket fire near the Tuileries. The screams and shouts. The clatter of wheels and hooves.

On the Quai d’Orsay and the Quai Theatines people are watching the battle on the other side of the river as if it is a firework display.

In the Rue Dauphine, his mind clears, not much but enough to realize where he is going. He has been here only once before, and then it was daylight and everything was normal. It takes him nearly an hour to find his way, casting to and fro in the near darkness, avoiding the crowds, avoiding the people who try to sweep him into their lives.

At last, not far from the Café Corazza, he stumbles on the narrow mouth of the alley. It leads to a paved court. The only light comes from an oil lamp on a second-floor windowsill. The lamp casts a faint dirty-yellow fragrance. The court has trapped the sun’s warmth during the day. It is even hotter than the street.

For a moment he listens. He hears nothing nearby except the scramble of rats, a sound grown so familiar he barely notices it.

He finds the door with the help of his fingertips not his eyes.

The wood is old and scarred and as dry as a desert. Charles hammers on it until his knuckles bleed. He hammers on it until it opens.

Marie is not much taller than he is. She is almost as wide as she is tall. She looks like a bull in a faded blue dress and carries with her a smell of sweat, garlic and woodsmoke, mingled with a sour, milky quality that is hers alone. Her smell is as familiar to Charles as anything in the world.

She draws him over the threshold and squeezes him in her arms so tightly that he finds it hard to breathe.

‘What happened?’ she says. ‘Where is Madame?’

She asks him questions over and over again and he cannot answer any of them. In the end she gives up. She brings water and a cloth and rinses the blood from his face and hands.

The only light in the room comes from the stump of a tallow candle and a rushlight on the unlit stove. That is why she does not see the clotted patches of blood in his hair. But her fingers find them. She makes the smacking noise with her lips that signifies her disapproval of something. With sudden violence, she strips off his breeches and his stained shirt. She drags him, white and naked, into the court.

There is a pump in one corner. She holds him under it with one hand and sluices water over him with the other. She runs her fingers through his wet hair, over every surface and into every crack and cranny of his slippery body. She rinses him again. With a hand on his neck, she pushes him in front of her into the room and bars the door behind them.

Despite the heat, Charles is shivering. She wraps him in a blanket, makes him sit on a stool and lean against the wall. She brings him water in a beaker made of wood.

He drinks greedily. She is humming quietly. She often does this, the same three notes, la-la-la, low and soft, over and over again.

He is glad that Luc is not there. Luc is Marie’s brother. He is a kitchen porter. He has only one eye, owing to a frightful accident in the slaughterhouse where he used to work. Though she did not witness it herself, Marie has described the accident to him many many times in graphic detail.

Charles’s one visit to this house, nearly a year ago, was so that he might see in person the angry red crater that was the site of Luc’s lost left eye. It was not as impressive in reality as in imagination. For the sake of his hosts, he acted out a polite pantomime of shock and horror. In truth, however, he was disappointed.

When Marie took him home again, he left a sou on the stove, because he knew that she and Luc were poor. Marie was Charles’s nurse when he was very young and later stayed as a maid. But then she was dismissed and the boy cried himself to sleep for nearly a week.

Now the brother and sister live in one room. Their bed is in a curtained alcove by the stove.

When Charles has had all the water he can drink, she brings in the chamber pot and watches him urinate. Afterwards she makes him kneel by the bed. She kneels beside him and says the prayer to the Virgin that she always says before he goes to sleep.

He knows that he is meant to join in. When he does not, she looks sharply at him and pokes him in the ribs. When she begins the prayer again, he moves his lips, mouthing shapes which have no words to them.

She watches him closely but does not seem to mind. Perhaps she does not know the difference between words that have shapes and words that do not.

Marie puts him into bed, blows out the candle and climbs in beside him. The mattress sinks beneath her weight. His body has no choice but to sink towards her and to mould its contours to hers.

It is very hot and it grows hotter. Now he is big he does not care for the way she smells or the way she looms over him like a mountain of flesh.

Soon she drifts into sleep. She snores and twitches.

The snoring stops. ‘Tell me,’ she whispers. ‘What happened? Where is Madame?’

He does not answer. He must never answer. Say nothing. Not a word.

Marie prods him again with her finger. ‘What happened?’

Tip-tap. Like cracking a walnut.

When he does not answer, she sighs noisily and turns her head away.

He listens to her breathing. He closes his eyes but then he sees what he does not wish to see. He opens them again and stares into the night.

Luc does not come back for three days. When he does, he is drunk with blood and brandy. The single eye is bloodshot.

He does not see the boy at first. He calls for wine. He calls for food. Marie tries to press her brother into the chair but he resists.

Charles is in the alcove, in the bed. He rolls a little to the left, hoping to conceal himself behind the half-drawn curtains. But Luc’s single eye catches the movement.

‘What the devil is that?’ he says in a voice so hoarse he can barely raise it above a whisper.

‘Madame von Streicher’s boy. He came the other night.’

‘Who brought him?’

‘No one.’

Luc advances towards the alcove and stares at Charles, who looks back at him because he doesn’t know what else to do.

‘Where’s your mother?’ Luc demands.

The boy says nothing.

‘I don’t know,’ Marie says. ‘He was covered with blood.’

‘Take him back. We don’t want him here.’

‘I tried,’ Marie says. ‘I sent a message to the Rue de Grenelle but Madame isn’t there any more. The concierge said she and the boy moved out a month ago.’

‘They are traitors,’ Luc says suddenly. ‘She’s been arrested. If we shelter him, they’ll arrest us too. You know where that ends.’ Luc makes a blade of his right hand and chops it down on the palm of his left.

He means the guillotine. Charles has heard his mother and Dr Gohlis talking about the machine, and Dr Gohlis said that it is a humane way to execute criminals. But, he said, the people do not like it because it is too swift and too clean a way to die. They prefer the old ways – hanging on wooden gallows, or death by sword or breaking on the wheel. They last longer, Dr Gohlis said, and they are more entertaining.

‘They’ve set up the machine at the Tuileries now. At the Place du Carrousel.’

Marie pours her brother wine. She stands, hands on hips, in front of the alcove, with the boy behind her.

Luc takes a long swallow of wine and wipes his mouth on the back of his hand. ‘Throw him out. In the gutter. Anywhere.’

‘I can’t. He’s only a child.’

‘If they find out he’s here, it’ll be enough to bring us before the Tribunal.’

‘But he couldn’t hurt a—’

Luc throws the beaker of wine at his sister, catching her on the face. She gives a cry and turns. Charles sees the blood on her cheek.

‘You will do as I say,’ Luc says. ‘Or I’ll break every bone in his body, and in yours.’

Chapter Two (#ulink_777f0683-10de-5dea-a2cf-64d76e886975)

Marie holds tightly to Charles’s arm. She pulls him from the shadowy, urine-scented safety of the alleyway leading to the court and into the crowded street.

She tugs him along, jerking his arm to hurry him up. He is a fish on a line, pulled through a river of people.

It is the first time he has been outside since the night he came to Marie’s. Everything is brighter, louder and noisier than it should be – the clothes, the cockades, the soldiers, the checkpoints, the swaying, seething parties of men and women. There is urgency in the air, an invisible miasma that touches everyone. He wants to be part of it.

Before they came out, Marie combed his hair. He is wearing his shirt and breeches, which she washed the day before, though her best efforts could not remove all the blood from them. They do not go north towards the river but west. They pass Saint-Sulpice and turn into the Rue du Bac.

Marie drags him across the street, threading their way through the coaches and wagons by force of personality and a steady stream of oaths. She stops outside a great house with black gates, studded with iron.

The black gates are shut. Marie mutters under her breath and tugs on the bell handle with her free hand. She does not let go of Charles with the other hand. She grips his wrist so tightly he fears it will snap.

The bell clangs on the other side of the gates but no one comes. Marie bounces up and down on her little feet. She rings the bell again. A passer-by jostles Charles, wrenching him from Marie’s grasp. He sprawls in the gutter and grazes his knees. Marie swears at the man and hauls him to his feet. She pulls the bell a third time, for longer and harder than before.

A shutter slides back in the wicket. A man’s eyes and nose are revealed in the small rectangle.

‘The house is shut up,’ he says. ‘Go away.’

‘Where’s Monsieur the Count?’ Marie demands.

‘Gone. All gone.’

The shutter slams home. Marie rings the bell again. She hammers on the door. Nothing happens.

She knocks again. By now a crowd has gathered, watchful and silent.

Marie turns from the gates and asks the bystanders what they think they’re staring at. Such is the force of her authority, of her anger, that they drift away, shamefaced.

Muttering under her breath, Marie leads Charles away from the gates in the direction of the Grand École. He starts to cry.

A slim gentleman is coming towards them on foot. His left leg drags behind him. He is dressed plainly in a dark green coat. Charles recognizes him and so does Marie.

She leaps forward into the man’s path and pushes the boy in front of her. ‘Monseigneur!’ she cries. ‘Monseigneur!’

He stops, frowning, his face suddenly wary. ‘Hush, hush – I am plain Monsieur Fournier now. You know that.’

‘Monsieur, you came to Madame von Streicher’s.’

He frowns at Marie. ‘I am sorry. There is nothing I can do for you. Whoever you are.’

‘Monsieur.’ She shoves the boy forward, so forcefully that he bumps against Monsieur Fournier’s arm. ‘This is Madame’s son. This is Charles. You must remember him.’

Monsieur Fournier has large brown eyes that open very wide as if life is a matter of endless astonishment to him.

‘This?’

‘Yes, monsieur, I swear it. On my life.’

Fournier motions them to move to one side with him. They stand by the outer wall of the great house. The passers-by ebb around them.

Fournier takes Charles’s chin in his hand and angles it upwards. ‘Yes, by God, you’re right.’ He bends closer, bringing his head almost on a level with the boy’s. ‘What happened? Are you hurt?’

Charles says nothing.

‘He won’t speak, monsieur,’ Marie says.

‘Of course he can speak.’ Monsieur Fournier touches Charles’s shoulder with a long white forefinger. ‘You know me, don’t you?’

‘He won’t say anything, monsieur. Not since that night.’

‘Are you saying he was actually there? When …?’ His voice tails away, rising into an unspoken question.

‘Have you seen Madame?’ Marie says. ‘Is she …?’ She runs out of words, too.

Fournier looks at her. ‘You weren’t there yourself?’

‘No, monsieur. I was at my – my brother’s house. Charles came to me in the night. He was …’

‘He was what?’ demands Fournier.

‘There was blood all over him.’ She paws at the faded stains on Charles’s shirt. ‘See? Everywhere. On his clothes, in his hair.’

‘Dear God.’

Her voice rises. ‘He won’t even tell me what happened. He won’t tell me anything. I can’t keep him at home. My brother will throw him out.’

‘You did well to bring him.’ Monsieur Fournier takes out a handkerchief and wipes his face. ‘We can’t talk here. Follow me.’

He sets off in the direction he came from, walking so rapidly despite his limp that Charles and Marie have to break into a trot to keep up. He takes the next turning, a lane running along the side of the house. There are no windows on the ground floor, only small ones high up in the wall, far above Charles’s head. These windows are protected by heavy grilles of iron bars, painted black like the gates.

They turn another corner into a narrow street parallel to the Rue du Bac. Here is another, much smaller gate set in the wall of the house.

Monsieur Fournier looks up and down the lane. There is no one else about. He knocks twice on the gate, pauses, knocks once, pauses again and then knocks twice again.

The shutter slides back. Nobody speaks. On the other side of the gate there is a rattling of bars. The key turns. The gate opens – not to its full extent, merely enough to allow a man to pass through.

Fournier is the first to enter. Marie pushes the boy after him. As she does so she ruffles his hair.

They are in a cobbled yard with a well in one corner. A fat old man in a dirty brown coat stares open-mouthed at them. Fournier limps towards the great grey cliff of the house. The old man jerks with his head towards the house, which means that Charles must follow.

Charles breaks into a run. Behind him, he hears the gate closing.

It is only when he is inside the house, when he is following Monsieur Fournier up a long flight of stone stairs that he realizes Marie is no longer there. She has stayed on the other side of the black gate.

The room is almost as large as a church. Despite the sunshine outside, it is gloomy, for the shutters are still across the windows. Light filters through the cracks. One of the shutters is slightly open and a bar of sunlight streams across the carpet to a huge desk.

The desk is made of a dark wood ornamented with gold which sparkles in the sunshine. Its top is as big as his mother’s bed and it has many drawers. It is covered in papers – some in piles, some lying loose as if blown by a gust of wind.

Behind the desk, facing into the room, is a stout gentleman whose face is in shadow. He looks up as Monsieur Fournier enters, and Charles recognizes him.

‘I thought you’d be halfway to—’ The gentleman sees Charles behind Monsieur Fournier. He breaks off what he is saying.

‘This is more important,’ Fournier says.

‘What the devil do you want with that boy?’

Fournier advances into the room with Charles trailing behind him. One of the piles of paper is weighted down with a pistol. Charles wishes that he were back with Marie, lying in her bed against her great flank and smelling her strange, unlovely smell.

‘You don’t understand. He’s Madame von Streicher’s son.’

Charles knows that this man is very important. He is Count de Quillon, the owner of this house, the Hotel de Quillon, and so much else. The Minister, Maman says, the godson of the King and once the King’s friend. He sometimes came to see Maman, though more often he would send a servant with a message and Maman would put on one of her best gowns and go away in his great coach.

Only now, when the Count rests his elbows on the desk, does the sunlight bring his face alive. He is a broad, heavy man, older than Fournier, with a small chin, a big nose and a high complexion.

‘This is Augusta’s son?’ the Count says. ‘This? Are you sure? Absolutely sure?’

‘Quite sure, despite the dirt and the rags.’

‘How does he come here?’

‘He ran away and went to an old servant’s. She brought him a moment ago.’

‘So was he with his mother when—’

Fournier interrupts: ‘I don’t know. He was covered in blood when he turned up at the old woman’s house.’

‘It is of the first importance that we discover what happened. Where is the servant? She must know something.’

‘She ran off as soon as we came through the gate.’

The men are talking as if Charles is not there. He might be invisible. Or he might not even exist at all. He cannot grasp this idea. Nevertheless, part of him quite likes it.

‘Come here, boy,’ says the Count.

Charles steps up to the desk. He makes himself stand very straight.

‘What happened at your house that night? The – the night you ran away?’

Charles does not speak.

‘Don’t be shy. I can’t abide a timid boy. Answer me. Who else was there? I must know.’

‘The woman said he simply won’t speak,’ says Fournier. ‘No reason why he shouldn’t, of course – he’s perfectly capable of it. I remember him chattering away ten to the dozen.’

‘Answer me!’ the Count roared, rearing up in his chair. ‘You will answer me.’

Tears run down Charles’s cheeks. He says nothing.

Fournier shifts his weight from his left leg. ‘Give the lad time to get his bearings,’ he suggests. ‘Gohlis can see him.’

‘We don’t have time for all that,’ the Count says. He adds rather petulantly, ‘Anyway, he’s not some lad or other – his name is Charles. I should know.’ He beckons Charles closer and studies the boy’s face. ‘Were you there? Did you see what happened to—’

‘My friend, I think this—’

The Count waves Fournier away. ‘Did you see what happened to your mother? Did you see who came?’

Charles stares at the pistol on the pile of papers. Is it loaded? If you cocked it and put it to your head and pulled the trigger, then would everything stop, just like that? Everything, including himself?

‘It is most important that you tell us,’ the Count says, raising his voice. ‘A matter of life and death. Answer me, Charles. Who was there?’

But Charles is still thinking about the pistol. If he shot himself, would St Peter take one look at him and send him down to the fires of hell? Or would there simply be nothing at all, a great emptiness with no people in it, living or dead?

‘Oh for God’s sake!’ the Count snaps.

The boy recoils as if he has been slapped.

‘Very well, then.’ The Count tugs the bell pull behind him. ‘We’ll talk to him when he’s past his absurd shyness. Someone will look after him and give him some food.’

Fournier rests a hand on Charles’s shoulder. ‘But what about later? If we leave?’

‘Then he comes with us.’ Monsieur de Quillon bends his great head over his papers. ‘Naturally.’

Chapter Three (#ulink_e103837d-f670-53f4-aee6-022592a39abf)

Charles is placed in the care of an elderly, half-blind woman. She lives in a room under the roof over the kitchen wing. Opening out of her chamber is a smaller one, which has a barred window. This is where Charles sleeps.

On the second night, he has bad dreams and he wets the bed.

On the third day, Monsieur Fournier summons him. He is in a salon overlooking the great courtyard at the heart of the Hotel de Quillon.

He is not alone. Dr Gohlis is there. He is another gentleman who used to call on Maman in the old days. He is young and stooping, a German from Hanover. He has cold hands.

In heavily accented French, the doctor asks Charles his name, and Charles does not answer. He asks Charles how old he is. Then he asks exactly the same questions in English and German, and all the while Charles stares out of the window at the weeds in the courtyard and imagines the words rising into the sky like startled birds.

Dr Gohlis examines him, looking at his teeth and poking at his belly with his forefinger. He walks behind Charles and claps his hands, making Charles twitch.

‘There is no physical cause for his silence that I can see. Everything is perfectly normal,’ he says. ‘You tell me he eats and moves his bowels. I could try purging or bleeding, but I doubt it would answer.’

‘He has sustained a great shock,’ Fournier says, throwing an unexpected smile at Charles. ‘Could that have disturbed his faculties and made him mute?’

‘Indeed, sir – that may very well be the case. If the hypothesis is correct, then it follows that the best course of treatment may be another shock. If one shock has removed his powers of speech, then a second may restore them.’

‘They say he wet the bed the other night.’

‘Really? Was he beaten for it?’

‘I do not know.’

‘If it happens again, I would advise it, for his own good. He will achieve nothing without discipline.’

‘Thank you, Doctor,’ Monsieur Fournier says after a moment. ‘I won’t detain you any longer.’

Dr Gohlis bows and leaves the room. He does not look at Charles, who is still standing by the window.

As the door closes, Fournier opens a bureau. He takes a sheet of paper from one of its drawers and a quill from another. He puts them on the flap and uncovers the inkstand. He places a gilt chair in front of the bureau.

‘Sit, dear boy. Take the quill.’

Charles obeys. He dips the pen in the ink without being asked.

‘Good,’ says Fournier. ‘Your mother told me that you are an apt student. Pray begin by writing your name.’

Charles bends his head. He writes. The quill scratches on the heavy paper.

‘Now write my name.’

Charles writes.

‘Excellent. And now – write the names of those who visited your mother in your cottage in the Rue de Richelieu.’

The pen moves again. The tip of the feather brushes Charles’s chin.

Monsieur Fournier comes to stand at his shoulder. ‘Let me see what you have written.’

Charles hands him the sheet of paper, the ink still glistening. He has answered each question with lines that go up and down, across and diagonally. They are black marks on white paper. They reveal nothing other than themselves.

The following morning, Charles wakes with the light.

Before he opens his eyes, he is aware of rustles and small movements which he thinks must be rats and mice, which come and go at will and treat the place as their own. He opens his eyes.

Without warning, his stomach gives a painful twitch as if someone has punched him there. He gasps and sits up in bed.

A boy is standing beside the window, his outline clearly visible in the light filtering through the cracks of the shutters. He is smaller than Charles and he is very still. He has his back to the room. He stands upright, his shoulders squared like a soldier on parade.

Just for an instant – for a hundredth of a second – Charles feels joy. He is not alone.

His feelings are no sooner there than they are gone. His lips move. They form the words: Who are you? But the words have no sound so the boy cannot hear them.

Charles is afraid as much as excited now. He swings his legs out of bed.

The boy does not move.

The boards are cold. Draughts swirl around Charles’s ankles and rise up his legs under his nightshirt. He shivers, partly from fear.

He takes a step nearer the window, nearer the boy. Then another, and another. Between each step he pauses. It is like the game he used to play with his mother when he was very, very young.

The strange boy does not even twitch. Step by step, Charles draws nearer to him. Still the boy does not move. He has been turned to stone, Charles thinks, he is a statue. He feels pity, though he knows the boy cannot really be like this; but, if he were, surely that would be even worse than losing your voice?

Charles takes a deep breath, stretches out a hand and touches the boy’s shoulder. It is cold, a little damp and hard – hard like wood, not stone. Charles walks around him and opens one of the shutters. The light from the window falls on the boy’s face.

Or rather – the light falls on the place where the face should have been.

The boy’s eye sockets are empty. There is nothing but a hole where the nose should be. The cheeks are sunken. The lips are almost gone. He still has some of his teeth. He is grinning. He will always grin because he can do nothing else.

Charles draws in a long, shuddering breath. His face contorted, he breathes out: a silent scream.

The door creaks. A current of cold air sweeps into the room.

Dr Gohlis is on the threshold.

‘I see you have found my little friend,’ he says in his strange, thick voice. ‘His name is Louis.’

As he speaks, he comes closer. Charles cannot move.

‘Who knows who this boy was?’ the doctor says. ‘Were you aware that before the Revolution, the poor were so desperate that they sent their children to prison – they sold them on the streets – they disposed of them like unwanted kittens?’

Charles stares at Dr Gohlis over the boy’s shoulder. He wishes with all his heart that the boy was still alive, that he was not alone with the doctor.

‘But even dead boys may be worth a few sous. In life they were quite useless to society. But in death, the lucky ones are granted the chance to serve a higher good.’

Dr Gohlis is standing by Louis’s shoulder now. He throws back the second shutter. More light floods over the boy. Charles covers his mouth with his hands when he sees what has been done.

‘So their parents take the money and drink themselves senseless in the nearest wine shop,’ the doctor continues. ‘And a man of science takes the boy.’ He stretches out a surprisingly long arm and grips the right wrist of the figure. ‘The dead boy. The man of science conveys the boy to another man, a man skilled in the art of flaying skin from a body. Believe me, it is not easy to do it properly, to do it well. It is one thing to remove the skin. It is quite another thing to do it without harming what lies beneath.’

The doctor releases the wrist. His fingertips play on the arm of the boy, patting it gently, rising from the wrist up to the elbow up to the shoulder and then to the neck. He points at a place on the neck.

‘See? This is the line of the great artery which carries blood to the heart. This is bone, here, and here the humerus, and here we have the scapula.’ The hand flutters higher. ‘Note the cheekbone. Do you see how some of the skin is still attached? The man who did this was truly an artist.’

The doctor’s hand sweeps down and grips Charles’s neck. Charles tries to pull away but Dr Gohlis tightens his hold. His hand is as cold as a dead thing, colder than the flayed boy.

‘After this boy was flayed, shall I tell you what happened then? He was covered in plaster, every inch of him. When the plaster was dry, they cut it open – and there is a mould of the dead boy. When you have a mould, you can make many copies. The copies are painted, in this case by another artist who is trained in the work of portraying what lies beneath, the inner mysteries under the skin. See how the muscle and tendon and bone stand out in their proper colours. Is it not a marvel?’

His grip is painfully tight. He forces Charles to move around the boy and to come closer. Now he is looking at the boy’s back.

‘These poor simulacra of humanity are called écorchés,’ Dr Gohlis says, ‘the flayed ones. Isn’t that droll? They assist in the instruction of students of medicine and drawing who are obliged to learn about the inward architecture of the human body. Observe.’

He picks up Charles’s right hand with his own left hand. Charles wills himself not to resist, not to pull away. The doctor forces him to extend his index finger. He runs the finger down the spine of the écorché.

‘Here are the cervical vertebrae,’ the doctor announces. ‘And below, in the middle of the spine, here are the thoracic ones. See the natural curve of the spine. Is it not elegant? And further below still, here are the lumbar vertebrae. They are much larger than the cervical ones, are they not? That is because they need to be, for they carry a greater burden.’

The doctor lowers his head to the same level as Charles’s.

‘You see?’ he says. ‘You will never forget this lesson, will you? Not while you live and breathe. You will always remember what lies beneath.’

He stares into Charles’s face. Charles stares back and thinks of nothing but the blank grey sky beyond the window.

‘Above all, you should draw this conclusion from it. You should remember that a boy who is useless in life may at least be useful in death.’ Dr Gohlis releases Charles’s neck and pushes him against the écorché boy. ‘You are no use at all to us if you will not talk.’

As he is speaking, Dr Gohlis moves towards the door. He pauses on the threshold.

‘I should examine him carefully if I were you. If you do not find your voice, you may be like that yourself one day.’

Chapter Four (#ulink_bc3e06b7-21b9-59bc-b481-830319677363)

On the very night before the letter arrived, Savill thought of Augusta. He had not thought of her for months, perhaps years. These were the dog days of the summer. Perhaps that had something to do with it, for the heat bred unhealthy desires. The long scar on his right cheek itched.

Before getting into bed, he had tied back the curtains and opened the window as wide as it would go. The smell from the cesspit wafted up from the yard beneath. These houses in Nightingale Lane were as old as Good Queen Bess, and so was their sanitation.

It was not the heat alone that kept him awake. He had the toothache, a savage sensation that drilled into the right-hand side of his jaw and sent tendrils of discomfort among the roots of the surrounding teeth. He had taken drops that had blunted the pain. But they did not send him to a comfortable oblivion: instead, they pinned his body to the bed while leaving his mind free and restless, skimming above the surface of sleep.

London was never quiet, even on the darkest night. He heard the watch calling the hours, the cries of drunken passers-by, the hammer-blows of hooves and the rumble of distant wagons bringing their loads through the night to Smithfield and Covent Garden.

The heat warmed the fancies of his brain to an unhealthy temperature and stirred into life the half-buried memory of another hot night. He had supped with fellow clerks at the American Department and returned late to the lodgings on the wrong side of Hill Street. It was their first married home. The apartments were too expensive for them but the address was genteel and Augusta had argued that a man did not rise in the world without seeming worthy to rise; and nor did his wife.

He found her sitting on the ottoman at the foot of the bed. There were two tall candles on the mantel. The edges of the room were dark, the corners populated with shifting shadows. But Augusta herself was coated with a soft golden glow.

She wore a simple white nightgown, so loose at the neck that it revealed most of her smooth shoulders. Her hair was down. She smiled up at him and held up her hand. The movement dislodged her gown and he glimpsed the swell of her breasts and the darkness between them.

This was how it had been in the beginning of their marriage: Savill had revelled in the contrast between Augusta by day and Augusta by night – the one icily elegant, ambitious to the point of ruthlessness, calculating yet so strangely foolish; and the other, everything a man could desire to find in his bed, and more. Even when he grew to dislike her, which did not take long, she retained her ability to excite him.

‘I have an appetite,’ she said that night as she sat astride him, her belly already swollen with Lizzie. ‘And you shall feed me.’

The excitement drained away from him, leaving a residue of bitterness, of regret, that mingled with the dreary ache of his tooth. The drops were making his head swim and they had given him a pain in his stomach. His eyes were full of sand. He felt nauseous but lacked the strength to roll out of bed and find the chamber pot.

At times like this, in these long, sleepless nights, Savill wondered whether he, too, had been to blame for what had happened. But that was folly. Memories are not real, he told himself, they are little more than waking dreams; and there is no guilt in dreams, neither hers nor mine, and no betrayals, either.

For are we not innocent when we dream?

The next morning, the servant brought up the letter when Savill was at breakfast with his sister and Lizzie. He noticed it had been franked by an obliging Member of Parliament in lieu of postage. He broke the heavy seal. As soon as he unfolded the letter he recognized the handwriting as that of a man who no doubt included many Members of Parliament among his intimate acquaintance.

The women were watching him. He read the letter twice. The questions crowded into his mind but he had long ago schooled his face not to betray his feelings.

Savill looked up. ‘I shall not dine with you today after all. I am obliged to go out of town on business.’ He registered the disappointment spreading over Lizzie’s face, then watched her instantly suppressing it. ‘Tomorrow,’ he said. ‘There’s always tomorrow.’

Why now? he wondered. Why a summons to Vardells, not Westminster? And again, and above all, why should Rampton want to see me now?

‘She is dead.’

Twelve feet above Savill’s head, plaster putti writhed, a pair of them in each corner of the salon. Each set of twins were shackled together with garlands. The infant boys had short, stubby limbs and plump, inflated bodies. Their eyes were sightless blanks, their lips slightly parted.

Give it time, Savill thought. He imagined the gilt and the whitewash fading and cracking, staining with candle grease, and the plaster crumbling and flaking from the ceiling: plaster snow.

‘Did you hear me, sir?’ Mr Rampton said.

The grandfather clock chimed. Savill counted the quarters and then the stroke of the hour: five.

‘Dead,’ Mr Rampton repeated, this time more loudly. ‘Augusta is dead.’

Savill’s eyes dropped slowly to the marble chimney piece. On one side of the fireplace was a bronze man with bulging muscles restraining a rearing horse with one arm while waving to something or someone with the other. What in heaven’s name was it all for?

Mr Rampton coughed. ‘Augusta. My niece, sir.’

Savill looked at him. ‘My wife, sir.’

Silence settled like dust in the air. Savill looked across the room at Rampton, who was sitting in the big wing armchair on the left of the fireplace. The chair was angled to catch the light from the two tall windows. Beside the chair was a lectern on wheels with candles on either side of the slope and a sturdy quarto, the pages held open with clips.

Rampton scratched the fingertips of his left hand on the arm of the chair. His face was wrinkled but still ruddy with the impression of good health. He looked smaller than he had been. Perhaps age was shrinking him as his fortune increased. The Lord giveth, as Savill’s father used to say with a certain grim satisfaction, and the Lord taketh away.

‘Of course,’ Rampton was saying, ‘your unhappy wife, Mr Savill, despite everything. And it is a cause for sorrow that the unfortunate woman is dead at last. We must not judge her. We may safely leave that to a higher power.’

Rampton was not a big man but he made good use of what he had. He wore a sober grey coat and very fine linen. His hair was his own but he still wore it powdered, a political statement in these changing times: a public demonstration of his attachment to old virtues and old loyalties. The heels of his shoes were higher than was usual for gentlemen’s shoes. He looked every inch a statesman, albeit a smallish one, which was a pretty fair description of what he was.

‘The poor woman,’ he went on. ‘Alas, she paid the price for flouting the laws of God and man.’

The rectangle of sky outside the nearer window was cloudless, a deep rich blue. Against this backdrop danced black specks, sweeping, diving and climbing with extraordinary rapidity. The swallows and the martins had begun their evening exercise. They would be vanishing soon as they did every year, though where they went, no man knew.

‘Those confounded swallows,’ Rampton said. ‘You cannot begin to comprehend the mess they make on the terrace.’ He too was staring out of the window; he too was glad of an excuse to think of something other than Augusta. ‘They nest under the eaves of the house or in the stables – I’ve tried for three years to get rid of them. But wherever they nest, they use my terrace as their privy.’

‘Where?’ Savill said.

‘What?’ Rampton turned from the window, away from the swallows, from one annoyance to another. ‘Paris. The foolish, foolish girl.’

‘How did you hear, sir?’

‘Through the Embassy. It happened just over a week ago.’

‘When the mob stormed the Tuileries?’

‘Yes. By all accounts the whole of Paris was delivered up to them. Riot, carnage, chaos. It beggars comprehension, sir, that such a civilized city should sink so low. The poor King and his family are prisoners. Tell me, when did you last hear from her?’

‘Five years ago,’ Savill said. ‘A little more. She wrote for money.’

‘And you sent it?’

‘Yes.’

Rampton grunted. ‘There was no necessity for you to do that.’

‘Perhaps not. But I did.’

‘On the other hand,’ Rampton said, ‘perhaps it was for the best. If you hadn’t, she might have been obliged to return to England.’

‘You mean she might still be alive?’

‘Would that really have been better? For her or for anyone else? For Elizabeth? After all, you could not have taken her in, even if you desired to, and she could not have been received anywhere.’

Rampton had lost all his teeth. As a result his voice had changed. Once it had been precise and hard edged, with every consonant squared off like a block of ashlar. Now the words emerged in a soft slurry of sound. No doubt he had a set of teeth, but he had not troubled to put them in for Savill.

Savill said, ‘She was in Geneva when she last wrote. She had parted from von Streicher, though she kept his name for appearance’s sake.’ The words still hurt when he said them aloud, but only his pride. ‘She said she had set up house with an Irish lady and they planned to take in pupils.’

‘Pupils? You did not believe her?’

‘I didn’t know what to believe. In any case, it didn’t signify. All that mattered was that she was in Geneva and she needed money.’

‘If she did not apply to you again, that suggests that she found it elsewhere.’

‘What were the circumstances of her death?’ Savill asked, his voice harsher than before. ‘Had she been in Paris for long? Who was she with?’

‘She had been there for several years. I believe she had granted her favours to a number of gentlemen since von Streicher’s departure. But I have not been able to ascertain whether she was under anyone’s protection at the time of her death. I’m afraid she was killed during the riots. I understand that a band of sans-culottes attacked her in the house where she had taken refuge.’

‘Was she alone?’

‘I believe so.’ Rampton took his spectacles from the lectern and turned them slowly in his hands. ‘Despite the German name she bore, you see, she was known to be British. It was said that she was a spy and she had been forced to leave her former lodgings for fear the mob would find her, or the police.’

‘Was she?’

‘A spy?’ Rampton shrugged. ‘Not as far as I know. Does it matter now?’

The frame of the glasses snapped between the lenses. Rampton stared at the wreckage in his hands. For a moment neither man spoke.

‘She was stabbed, I understand,’ Rampton went on in a rush. ‘It must have been a quick death, at least. And the place was ransacked.’

Savill turned his head so Rampton could not see his face. He thought of Augusta as she had been when he had first seen her: at Mr Rampton’s house in Westminster. Seventeen, coolly beautiful even then, with a way of looking at you that would heat the blood of any man. Ice and fire.

‘We must look ahead,’ Rampton said. ‘Sad though this occasion is, sir, I believe I should congratulate you.’

Savill stared at him. ‘What?’

‘You are free at last, sir. Should you wish to marry again, there is now no impediment to your doing so. Your unhappy condition, this limbo you have been in, cannot have been easy for you.’

That was true enough. Augusta had given Savill ample grounds for divorce when she eloped so publicly with her German lover to the Continent, while he himself had been three thousand miles away in America. But divorce was a rich man’s luxury, even when the husband was so clearly the injured party.

‘This will draw a line under the whole sad affair,’ Mr Rampton went on.

‘She was my wife, sir,’ Savill said. ‘Not an affair.’

Rampton spread his hands. ‘My dear sir, I intended no disrespect to the dead.’ He folded his hands on his lap. ‘I fear I have been clumsy. You have had a shock. Will you take a glass of wine? A cup of tea?’

‘Thank you, no. Tell me the rest.’

‘I do not yet know the whole of it. But I am told that someone informed a friend of hers, a Monsieur Fournier, and he communicated with the Embassy. Everything was done as it should be, which must be a great comfort. There was a doctor in attendance to certify the death. A notary took down a statement concerning the circumstances of her demise, and it was signed by witnesses.’

Savill gazed out of the window. The swallows were still there but they had moved further away. Like charred leaves above a bonfire, he thought. A pyre.

Rampton cleared his throat. ‘It would give me great pleasure if you would stay and dine.’

‘Thank you, but I believe I shall ride back to London.’

‘There’s plenty of time yet,’ Rampton said. ‘And there is something else that we need to discuss which may perhaps take a while.’

Rampton paused. Savill said nothing.

‘There are the documents I mentioned,’ Rampton said. ‘The notary’s statement and the death certificate.’

‘If you have them, sir, I shall take them now,’ Savill said. ‘If not, then perhaps you would send them to me. You know my direction. Nightingale Lane, near Bedford Square.’

‘I don’t have them. They are in the possession of Monsieur Fournier. And he has something else of hers that may interest you.’

‘I doubt it,’ Savill said, rising from his chair. ‘There is nothing of my late wife’s that interests me.’

‘The matter is more delicate than it first might appear,’ Mr Rampton said. ‘And that is why I asked you to wait on me here at Vardells and not in town.’ He smiled up at Savill with unexpected sweetness. ‘Augusta had a son.’

Chapter Five (#ulink_9c8689c6-82ca-59ce-b1e9-aabde01a9f6c)

‘That scar on your cheek from New York,’ Rampton said when they were at table. ‘I had expected the wound to have healed better over the years. Does it pain you?’

‘Not at all,’ Savill said. ‘Why should it, after all this time?’

‘I’m rejoiced to hear it, sir.’

Rampton had ordered the curtains drawn and the candles lit, shutting out the blue sky and the swallows. Even in the country, he lived in some state. There were two manservants to wait at table. The food was good and the wine was better. The presence of the servants kept the conversation on general topics.

‘And how is your little daughter?’ he asked as Savill was helping himself to a delicately flavoured fricassee of chicken.

‘Lizzie?’ Savill glanced down the table. ‘Your goddaughter is in good health, sir, but she is not so little now.’

‘Good, good.’ Rampton nodded and looked pleased: it was as if the excellence of Lizzie’s health was something he himself had worked towards, something for which he could take credit, had he not modestly waived his right to it. ‘Is she like her mother?’

‘Yes. In appearance. Her face is softer, perhaps, gentler.’

‘As long as her character does not resemble her mother’s. Let us pray it does not.’

Savill said nothing.

‘Her mother was very beautiful at her age. If Elizabeth takes after her, she will have plenty of suitors. I dare say she will soon be of an age to marry.’

‘Should she wish to, sir, yes. If she finds a man who pleases her.’

‘If you take my advice, sir, you will encourage her to do so as soon as possible.’ Rampton dabbed his lips with his napkin. ‘Though it’s an expensive business, of course. Marriage, I mean. However one looks at it.’ He applied himself to a dish of lamb cutlets.

Savill sensed something unsaid here; he caught the ghost of its absence. ‘Is this your main residence now, sir?’ he asked.

‘Alas, no – I am much at Westminster. I must own I wish it were otherwise. I find I have a taste for country life. Of course this is little more than a cottage, and there’s barely fifty acres with it. But it’s enough for my simple wants. I’m building a wing to accommodate my library with bedrooms above, with a fine prospect over the garden. In the spring, I shall improve the prospect still further by sweeping away those old hedgerows and farm buildings to the west of the drive. Then it will be perfection.’

If this is a cottage, Savill thought, then I am a unicorn. The house had been refurbished since he had last been here. It now sat in grounds that were in the process of being newly laid out; on the east side of the drive, a great expanse of grass swept towards a small lake that had not been there before. As for the house, the new wing would increase its volume almost by half as much again. The work was nearly finished. Earlier in the day, carpenters had been fitting the French windows that would open from the library to the terrace.

‘Will you retire here, sir?’

‘Retire?’ Rampton smiled. ‘I doubt my masters would permit me to do that, not while this crisis continues in France. And God knows how long that will last. I tell you frankly, sir, I see no sign of its ending.’

‘You do not think that the King and the National Convention will come to an accommodation?’

Rampton’s smile did not waver. ‘That is for wiser heads than yours or mine to decide.’ He turned the subject smoothly. ‘But when I do retire, it will be delightful to be here.’

‘Will you not find it sadly dull?’

‘Not in the slightest. I shall have my books, of course, and I have a mind to turn farmer.’ Rampton crooked his finger at the servant who sprang from the shadows to refill Savill’s glass. ‘I have bought two or three tenanted farms nearby. I may take them into my own hands. A toast, sir – to your Elizabeth. May she find herself a husband that suits you both.’

Savill drank. He had once been a civil servant, and in those days he had known Mr Rampton’s ways as a dog knows his master’s. Rampton had not been talking idly during the meal. He had been making sure that Savill understood him.

‘I am rich,’ he was saying, ‘and I have the ear of powerful men, so you would be wise to oblige me. For your daughter’s sake as well as your own.’

With unnatural reverence, the servants removed the cloth and set out the wine, the nuts and the fruit. Rampton signalled for them to withdraw. The two men were sitting side by side now.

Savill bit down on a walnut and a stab of pain drove into his jaw. He twitched on his chair but managed to avoid crying out. He must find time to have the offending tooth pulled out. The truth was, he told himself, he was a coward where his teeth were concerned.

‘A toast, sir,’ Rampton said.

Savill pushed aside his plate and took up his glass with relief. They drank His Majesty’s health. Avoiding each other’s eyes, they drank to Augusta’s memory. Then the conversation faltered.

‘His name is Charles,’ Rampton snapped, as if Savill had said it was something quite different. ‘He must be about ten or eleven years old. Thereabouts.’

‘Do you know who his father is?’

Rampton cracked his knuckles, in the old days a sign of calculation; his clerks had mocked him for it, but only when they were safely out of his way. ‘I have not been able to ascertain that. I believe Augusta had left the Bavarian gentleman by then and was living in Rome, but my information is not exact.’

‘Does Charles speak English?’ Savill said.

‘The question had not occurred to me. I suppose, if he was born in Italy and he has spent the last few years in France …’ Rampton turned away and stared up at a portrait of himself. ‘Still,’ he went on in a quieter voice, ‘at his age it hardly signifies. The mind of a child is as porous as a sponge. It soaks up whatever you pour into it with extraordinary rapidity.’

‘If his father cannot be found, no doubt his mother’s friends will care for him. Where is he staying?’

‘The Embassy will let me know as soon as they hear.’

‘He’s nothing to do with me,’ Savill said, more loudly than he had intended. ‘He’s Augusta’s bastard.’

‘Pray moderate your voice, sir. You do not want the world to know your business.’

‘But it is not my business, sir. That’s my point.’

Rampton refilled their glasses. ‘The law would say otherwise. Augusta was still your wife at the time of her death. You and she were not divorced. I understand that she did not even leave a will, which makes you her heir. The child’s paternity is not established, and probably never will be. In sum, this is one of those cases where the law and common sense point in the same direction as a man’s duty as a Christian. The boy is your responsibility.’

‘Nonsense.’

To Savill’s surprise, Rampton smiled. ‘I thought you would say that. And, that being the case, my dear sir, let me propose a solution.’

‘You may propose what you wish, sir. It is nothing to do with me.’

Rampton leaned closer. ‘What if I take the boy myself?’

Chapter Six (#ulink_117d969f-bf9f-513c-9d10-8509c49f216a)

Charles dreams of the boy called Louis.

He, Charles, is lying on his bed and Louis is standing by the window. This is similar to what actually happened when Dr Gohlis came at dawn that morning. But, in the dream, Charles already knows Louis’s name. He also knows that Louis is alone and naked in the world.

In the dream the light is much stronger than it was in real life. It floods over the doubly naked body of Louis. The colours glow like the stained glass in Notre Dame. Who would have thought there would be so many colours under a boy’s skin?

Charles glances down at his own body. He discovers that, though it is daytime, he is not wearing any clothes. Nor is he lying under the bedclothes. Like Louis, he has lost most of his skin. He sees rope-like arteries, the blue filigree of veins, the slabs of muscle, the shiny white knobs of bone. He too has become doubly naked.

He too has become beautiful.

Louis stares out of the window. But now he turns, his head leading his body. Charles sees his ruined face. Louis smiles, though of course it is not easy to tell that he is smiling because his lips and skin are gone and so has most of his facial tissue.

Louis holds out his right hand towards Charles. The gesture is unmistakably friendly. Charles tries to smile in return. That is, he thinks a smile, but he knows that he too lacks lips and skin so the smile may not be obvious.

He raises his right hand. It looks webbed, like a duck’s foot or the ribbed leaf of a cabbage.

‘Hello, Louis,’ he says.

Day by day, the house in the Rue du Bac empties itself of people and things. It also empties itself of its invisible contents, its rules, its habits, its regime. Charles does almost as he pleases now. He is under no restraint as long as he does not try to leave.

The servants are slipping away, despite the guards at the gates and doors leading to the outer world. They leave their tasks half-done – a mop standing in a pail of dirty water in a corner of the grand staircase; a drawing room with only a third of the furniture covered up and the pictures and ornaments ranged along one wall on the floor with the packing materials beside them.

The house is sliding into an unknown, unpredictable future, just as Charles is. He wanders from room to room, from salon to hall, from attic to cellar, frequently losing his way. The old woman who was meant to be looking after him is hardly ever there. He realizes after a while that he has not seen her for days. Perhaps she is dead.

Time itself loses its familiar markers, the hours of the day, the days of the week. There are many clocks in this house but no one troubles to wind them now or to set their hands. So time disintegrates into a variety of smaller times: and soon there will be no time at all.

Now that the old woman no longer brings him food, he is obliged to forage for it himself. He finds his way to the vaulted kitchens whose cellars run under the street.

In the city outside, people are starving. Here there is more food than anyone could ever eat. There are vegetables rotting down to brown mush; joints of meat turning grey and breeding maggots; and bins of flour that feed a shifting population of insects and small animals.

There are still people who cook and serve food, however, and their leftovers lie around the kitchens. There is water from the pump that serves the scullery tap. On one occasion he drinks a pot of cold coffee. On another he finds a bottle of wine nearly half full. The wine is golden and silky sweet. It cloys in his mouth. He drinks it all. It makes him sick and then sends him to sleep: he has a bad dream in which blood drips on him from a black sky streaked with flickering yellow; and he wakes with a headache.

He spends hours watching the Rue du Bac through the cracks in the shutters in what used to be the steward’s room. He stares down at the hats and heads bobbing to and fro and listens to the grinding roar of wheels and the shouting. Sometimes he hears a popping sound in the distance which he thinks is musketry.

Charles encounters the Abbé Viré. The old man wanders restlessly about the halls and stairs, his slippers shuffling like falling plaster on the marble and the stone. His cassock is stained with old food.

In the old days, Maman would take him to the Abbé for instruction in religion and tuition in mathematics and the classical authors. When Charles was very young, he believed Father Viré to be the earthly form of God.

All this makes the priest’s present conduct unsettling in the extreme. The Abbé does not appear to recognize Charles. He usually ignores him completely. He carries a breviary as he walks and reads from it, muttering to himself.

Once, Father Viré comes across Charles trying to read a ten-day-old newspaper in a disused powder-closet. The old priest raises his hand and sketches a blessing over Charles’s head, murmuring the familiar words into the dusty air.

As for the Count de Quillon, he stays in his suite of private apartments beyond the grand salon. Monsieur Fournier comes and goes. When he sees Charles, he often stops to ask how he does and whether he needs anything. Charles does not answer.

‘All will be well soon,’ he says one morning. ‘You’ll see.’

But Charles knows that nothing will ever be well and that the only thing he will see is more of what he sees now. Still, it is good of Monsieur Fournier to tell kind lies.

Sometimes they ask him the questions again – Fournier, the Count and Dr Gohlis. Always the same ones. What happened on the night your mother died? Did you see who was there? What was said?

Say nothing. Not a word to anyone.

One day, a wagon comes into the main courtyard, where the weeds are advancing in ragged green lines along the cracks between the flagstones. Men bring packing cases and begin to put things in them – pictures, statues, clocks and carpets. Some of the clocks are still ticking. They are nailed up alive in their coffins.

The remaining servants, working in relays, bring trunks and valises from the attics. They fill them with books, papers and clothes. Two more wagons come down the lane at the back of the house with a guard of armed men. They are loaded with the heavier items. They go away during the night. So do more of the servants, and then the house is emptier than ever.

As the people and the objects seep away from the Hotel de Quillon, Charles notices how shabby everything is – the damp patches on the plaster in the grand salon where the old tapestries used to hang; the cracks that snake across the ornate ceiling of the ladies’ withdrawing room; the leak in the roof of the room next to his which, one rainy night, brings down the whole ceiling.

Charles does not like the nighttimes because sometimes he wets the bed. This often happens on the nights after they have asked him the questions.

When he wets the bed, he is beaten the following morning. He understands this. He has done wrong. Since the old woman disappeared, no one notices if he wets the bed so it no longer matters.

One night, Dr Gohlis comes into Charles’s room and wakes him from a deep sleep. He squeezes the boy’s chin between finger and thumb. He holds the candle so Charles can see his face, orange and gold in the light of the flame.

‘Remember my écorché boy?’ he says. ‘Are you going to be like him one day?’

Charles knows that the écorché boy is called Louis. He is kept in the sitting room that has been set aside for the doctor’s use at the Hotel de Quillon. The door is locked when the doctor is not there.

One morning, Charles watches the doctor leave. He sees him hide the key on the ledge of the lintel above the door. Now Charles can visit Louis.

Often he chooses the very early morning when few people are stirring and the doctor is unlikely to be there. The écorché boy stands beside the doctor’s desk. Charles examines him carefully and presses his own body to see if he is the same underneath, under all that skin. He thinks of conversations they might have and games they might play. He likes to touch Louis and wishes that Louis could touch him. Once he kisses Louis’s cheek and he has the impression that Louis’s face is slightly wet, as if he has been crying.

One day the key is not on the lintel. The door is locked. Dr Gohlis is not there.

Who is left? Charles thinks there are perhaps half a dozen servants, the old abbé and himself. He cannot remember when he last saw the Count or Monsieur Fournier or Louis.

What will happen to me, Charles wonders. Will they leave me quite alone?

Then comes the night when everything changes. Just before dawn, Dr Gohlis wakes Charles, makes him dress and takes him downstairs. An old servant waits with two small valises in the hall.

Charles wants to say: ‘Where are we going?’ He also wants to ask Dr Gohlis what has happened to Louis.

But of course he cannot speak. He must not speak.

Not a word to anyone.

Chapter Seven (#ulink_39e10f17-d915-5d53-8dd8-422bf5f32c80)

‘Mr Savill – may I make known Mr Malbourne, my clerk?’ Rampton said, enunciating the words with precision because he was wearing a set of ivory teeth. ‘Mr Malbourne – Mr Savill.’

They bowed to each other. Malbourne was a slender man with delicate, well-formed features and the address of a gentleman. Savill had found him and Rampton at work in the study when he arrived. The clerk’s right arm was in a black-silk sling, though he removed it when it was necessary for him to write.

This was Savill’s second visit to Vardells, nearly a month after his first, prompted by a letter from Rampton. It was late September now, and the leaves were turning on the lime trees beside the drive.

‘Mr Malbourne has intelligence that relates to Mrs Savill’s son,’ Rampton said. ‘It appears that Charles has been brought to England.’ He gestured to his clerk that he should continue.

‘Charles is living in the country with a party of newly arrived émigrés,’ Malbourne said. ‘Fleeing the massacres. There has been quite a flood of them.’

‘Where are they?’

‘They have taken a house in Somersetshire a few miles beyond Bath. Charnwood Court in the village of Norbury. The émigrés are people of some position in the world. Have you heard of the Count de Quillon?’

‘The late minister?’

‘Precisely. Though he held the seals of office for no more than three or four weeks before he was forced to resign.’

‘He was the old king’s godson,’ Rampton said. ‘Some say it was a nearer connection still, through his mother, and that was why he was in such favour at Versailles when he was a young man. This king made him a Chevalier of St Louis. Not that it stopped him from dabbling with the Revolution when it suited his purpose.’

‘The point is, sir,’ Malbourne went on, ‘Monsieur de Quillon is altogether the grand gentleman. He is not an easy man to deal with. He is accustomed to having his own way, to moving in the great world.’

‘Then why has he buried himself in the country?’ Savill asked.

‘Because his resources are limited,’ Malbourne said. ‘Most of his fortune is in France, and it has been seized. His estates have been sequestered. Also he and his allies have not many friends in London. After all, they are dangerous revolutionaries themselves: they tried to manipulate their king to their own advantage.’

‘Their chickens have come home to roost,’ Rampton observed.

‘Indeed, sir,’ Malbourne continued. ‘Moreover, they are detested by those of their fellow countrymen already in London, who have never wavered from their old allegiance to King Louis and never compromised their principles.’

‘Very true,’ Rampton said. ‘And, to speak plainly, my dear Savill, the Count and his friends have such a history of fomenting sedition, of flirting with the mob, that we ourselves have little desire to play host to them.’

‘Yet you let them come here.’

‘Unfortunately we lack the legal instruments to prevent it,’ Malbourne said.

‘For the time being,’ Rampton said. ‘But that is neither here nor there. Tell him about Fournier.’

‘Fournier?’ Savill said. ‘The man who dealt with the funeral arrangements?’

Malbourne bowed. ‘Yes, sir. He is the Count’s principal ally. Fournier preceded Monsieur de Quillon to England. Indeed, I believe Charnwood is leased to him, not the Count. He is a younger son of the Marquis de St Étienne and was the Bishop of Lodève under the old regime. But he has resigned his orders and now prefers to be known simply as Fournier.’ He smiled. ‘Citizen Fournier, no doubt.’

‘An atheist, they say,’ Rampton said sourly. ‘The worst of men.’

‘Mind you keep your seat this time,’ Rampton said as Malbourne was leaving.

Malbourne saluted them with his whip. ‘I’ll do my best, sir.’

He rode down the drive, urging his horse to a trot and then to a canter.

‘Foolish young man,’ Rampton said fondly. ‘He sprained his arm last month when he had a tumble. Hence the sling. It cannot be denied that there’s a reckless streak to Horace.’ He smiled. ‘Just as there was to his grandfather. That’s where the money went, you know, and the estates. He gambled as if his life depended on it – Vingt-et-un.’

Horse and rider were out of sight now but Savill heard the drumming of the hooves accelerate to a gallop.

Rampton stared along the terrace, at the far end of which two workmen were building a low wall. ‘Look, sir. Those damned swallows. They are already smearing their filth on my new library.’

‘Is Mr Malbourne in a hurry or does he always ride like that?’ Savill said.

‘He is expected at the Woorgreens’ this evening and he will not wish to be late.’ Rampton glanced at Savill and decided to enlighten his ignorance. ‘Mr Woorgreen, the East India Nabob. He is betrothed to the younger Miss Woorgreen. He will have twelve hundred a year by it, I believe. There’s also the consideration that her mother’s brother is a friend of Mr Pitt’s.’

They went into the house. Savill was engaged to dine and spend the night.

‘Horace Malbourne is a man of parts,’ Rampton said, leading the way into the study. ‘Well connected too. But if he wishes to get on in the world, he knows he must set aside his wild oats and marry money. If all goes well, we shall see him in Parliament in a year or two.’

How very agreeable it must be, Savill thought, to have one’s life mapped out like that: a comfortable place in a government office, a rich wife, a seat in Parliament.

‘He was my ward, you know – his poor mama entrusted him to me when she died.’ Rampton rang the bell and sat down before the fire. ‘But he has amply repaid my care and now he is most valuable to me. When he marries, though, he will spread his wings and fly away.’

Like a swallow, Savill thought, when winter comes.

The manservant came and Rampton gave orders for dinner. Savill wondered whether the introduction of Mr Malbourne had been designed to serve a secondary purpose: to show Savill that Rampton was worthy to stand in the place of a father; that he might safely be entrusted with the care of Augusta’s son.

‘By the way,’ Rampton went on, ‘I have not confided in him that I may adopt Charles.’

‘Because that has not been settled, sir.’

‘Quite so. But in any case I think it better that Malbourne believes that I’m assisting you to win control of the boy solely in view of our family connection. Also, of course, it’s in the Government’s interest to know more about the household at Charnwood and what they are doing.’

Soon afterwards, they went into dinner. Savill had not accepted Rampton’s proposition, but the very fact of his being here was significant, and they both knew it. Rampton had the sense not to press home his advantage. Instead he talked with an appearance of frankness about the situation in France and the Government’s policy towards it.

It was almost enjoyable, Savill found, to talk with Rampton on a footing that, if not precisely equal, was at least one of independence. Once upon a time, Rampton had been his unwilling patron because Savill had married his niece. He, Savill, had served as one of his clerks in the American Department during the late war, though he had never been in such high favour as the elegant Mr Malbourne.

Despite himself, he was impressed by his host. Rampton’s career had collapsed near the end of the war, when the King had dismissed the American secretary and closed down the entire department. Yet, somehow, he had clawed his way back.