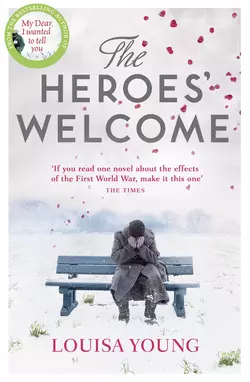

The Heroes’ Welcome

Louisa Young

The Heroes’ Welcome is the incandescent sequel to the bestselling R&J pick My Dear, I Wanted to Tell You. Its evocation of a time deeply wounded by the pain of WW1 will capture and beguile readers fresh to Louisa Young’s wonderful writing, and those previously enthralled by the stories of Nadine and Riley, Rose, Peter and Julia.LONDON, 1919Two couples, both in love, both in tatters, come home to a changed world.When childhood sweethearts Riley and Nadine marry, it is a blessing on the peace that now reigns. But the newlyweds and their old friends Peter and Julia Locke wear the ravages of the Great War in very different ways. Where Nadine and Riley do their best to forge ahead and muster hope, Peter retreats into drink and nightmares, unable to bear the domestic life for which Julia pines.

Copyright (#u4da12643-0db2-5a5f-ab42-af1f3a2b5c31)

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by The Borough Press 2014

Copyright © Louisa Young 2014

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover photographs © Stephen Mulcahey / Arcangel Images (main image); Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com) (petals, grass and snowdrops).

Excerpts from The Odyssey by Homer, translated by Robert Fagles, translation copyright © 1996 by Robert Fagles. Used by permission of Viking Penguin, a division of Penguin Group (USA) LLC.

Louisa Young asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. Some characters (or names) and incidents portrayed in it, while based on real historical figures, are the work of the author’s imagination.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books

Source ISBN: 9780007361472

Ebook Edition © 2015 ISBN: 9780007361489

Version: 2015-02-24

Praise for The Heroes’ Welcome: (#u4da12643-0db2-5a5f-ab42-af1f3a2b5c31)

‘Fierce and tender, The Heroes’ Welcome depicts heroism on the grand scale and the importance of the tiniest act of courage’

Observer

‘Young possesses in abundance emotional conviction, pace and imaginative energy, and these qualities will draw readers with her through time and space, as she unfolds the story of the Lockes and Purefoys on their journey through the 20th century’

HELEN DUNMORE, Guardian

‘If you read one novel about the effects of the First World War this year, make it this one. It has brain with its brawn and deserves a hero’s welcome’

The Times

‘Powerful, sometimes shocking, boldly conceived, it fixes on war’s lingering trauma to show how people adapt – or not – and is irradiated by anger and pity’

Sunday Times

‘Energy and charm’

Evening Standard

‘A moving exploration of the war’s toll on a generation … deeply affecting’

Metro

‘A brilliant, passionate, intense examination of what it is to survive a war and to negotiate a peace with a body and mind that have been irrevocably altered’

ELIZABETH BUCHAN

Dedication (#u4da12643-0db2-5a5f-ab42-af1f3a2b5c31)

RJL

RIP

‘Joy, warm as the joy that shipwrecked sailors feel when they catch sight of the land … only a few escape, swimming and struggling out of the frothing surf to reach the shore, their bodies crusted with salt but buoyed up with joy as they plant their feet on solid ground again, spared a deadly fate. So joyous now to her the sight of her husband, vivid in her gaze, that her white arms, embracing his neck, would never for a moment let him go …’

from TheOdyssey,

trs Fagles

‘I knew that I was more than the something which had been looking out all that day upon the visible earth and thinking and speaking and tasting friendship. Somewhere – close at hand in that rosy thicket or far off beyond the ribs of sunset – I was gathered up with an immortal company, where I and poet and lover and flower and cloud and star were equals, as all the little leaves were equal ruffling before the gusts, or sleeping and carved out of the silentness. And in that company I learned that I am something which no fortune can touch, whether I be soon to die or long years away. Things will happen which will trample and pierce, but I shall go on, something that is here and there like the wind, something unconquerable, something not to be separated from the dark earth and the light sky, a strong citizen of infinity and eternity. The confidence and ease had become a deep joy; I knew that I could not do without the Infinite, nor the Infinite without me.’

‘The Stile’

from Light and Twilight,

by Edward Thomas

‘It has taken some ten years for my blood to recover.’

from Goodbye to All That

by Robert Graves

Table of Contents

Cover (#uf4df9c06-1777-5b47-98b6-32a500089064)

Title Page (#u3286e141-391e-5d54-a5e5-39d52ab045ea)

Copyright (#u6f05a933-e736-5348-892f-577e13e783f9)

Praise for The Heroes’ Welcome (#u24ca9819-3765-531c-8481-a551a8160ee4)

Dedication (#u11e10c1a-8dcf-596c-98f5-9e515901a418)

Epigraph (#u7bd06175-4c64-51b2-955a-92d9af4e4cda)

Part One: 1919 (#ud61b3bc6-06c1-5fb1-9bb1-6d6553909be7)

Chapter One (#u4b667220-82a2-5bb5-9d8b-7b524444d76a)

Chapter Two (#ufd007067-2d78-514f-a597-88b0b72e11b3)

Chapter Three (#uffe9bc7c-8903-5dd0-b6b8-5887384dcc9c)

Chapter Four (#u890f086b-bc81-572f-8351-c4cd920239c6)

Chapter Five (#u6ac2f61f-6ef9-5f49-a4cc-78a87349b086)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Two: 1919 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-one (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three: 1927 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-four (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Louisa Young (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Part One (#u4da12643-0db2-5a5f-ab42-af1f3a2b5c31)

Chapter One (#ulink_3c1446fc-31ab-5a8e-9b1a-7a3b85d645c4)

London, March 1919

Riley Purefoy did not think very much about the war. He didn’t have to. It was part of him. If others mentioned it …

… but then they didn’t: neither the other old soldiers, who had, most of them, realised very quickly that nobody wanted to hear what they might have to say, nor the civilians, who drifted away at the same rate as the soldiers fell silent.

Phrases and scraps, from time to time, slithered back at him. There was a taste in his throat sometimes, unidentified. There was an insistent image of bits of coughed-up gassed lung on the floor of an ambulance, which brought with it the necessity of standing still for a moment. There were moments still, a year and a half after he had stumbled off the battlefield, when the silence confused him as dry land confuses a sailor’s legs. There was Peter Locke’s voice, saying: ‘Then you’re in charge, old boy.’ This last stuck with him, because he knew that however unlikely it seemed, this remained largely true. He was in charge.

Despite his physical damage, Riley was well equipped: a sturdy young man, clear-eyed. So as the months went by, when he did think of war, he thought more of future war, and how to prevent it; of the future children, and how to keep them safe from it, or of the future of his fellow wounded, and how to improve it. He saw people look at him with pity and doubt. He registered the small (or large) involuntary gasps that his scarred face provoked. When a taxi driver drove off because he couldn’t understand what Riley was saying, Riley did his best to conjure sympathy for the man’s embarrassment over natural fucking anger at this continued humiliation.

He was quite aware that not many people thought he’d add up to much, poor fellow. But if he learnt anything from being shot to bits and patched up again, it was this: now is a good time to do what you want.

Riley Purefoy and Nadine Waveney married under a daftly beautiful wave of London blossom cresting over a city that had been at war for so long that it didn’t know what to do with itself. On the wall of the register office a sign read: ‘No Confetti – Defence of the Realm Act’. The flying blossom storm took no notice of that, dizzying eddies of it on the spring breeze, and mad sugar-pink drifts accumulating against the damp Chelsea kerbstones. Nadine, still so skinny she wasn’t having her monthlies, wore Riley’s vest under Julia Locke’s utterly out-of-date wedding dress from before the war, taken in. Riley was in uniform. Peter Locke, Riley’s former CO, tall, courteous and almost sober, was best man. Peter’s cousin Rose was maid of honour, in white gloves, and his son Tom, flaxen-haired symbol of innocence and possibility, was the pageboy. No one else was there. Tom’s mother, Julia, had picked early white lilac and given it to Rose to bring up from Locke Hill, but she didn’t come herself. She was not well enough, or perhaps just embarrassed. It had only been a few months since her own crisis. It had only been a few months since everything.

Afterwards, they went to the pub across the road where, it turned out, Peter had earlier deposited two bottles of Krug ’04, acquired he didn’t care to say how. Rose was in the dark green tweed suit that she’d worn to Peter and Julia’s wedding (though she thought she wouldn’t mention that), and confessed to a small thrill of shame to be in a pub. It was a beautiful ceremony and a happy day. Any fear that anyone might have had for the future of the marriage, its precipitous start, the battered souls of the bride and groom, lay unmentioned. It was a great time for not mentioning. No one wanted to remind anyone of anything. As though anyone had forgotten.

The bride and groom were to spend the wedding night at Peter’s mother’s house in Chester Square, where the tall handsome rooms were still draped with dustsheets and the chandeliers swathed in pale holland, because the old lady still didn’t dare come down from Scotland.

They had not kissed. How could they? Through the long quiet winter of 1918–19 at Locke Hill, Nadine (so jumpy and tender, crop-headed) and he (damaged) had taken long walks with their arms around each other, spent long days curled up together on the chintz sofa, and failed over and over to go to bed at all, because they could not go to bed together, and did not want to part. They had paused, like bulbs underground in winter, immobilised, and reverted to a kind of reinvented virginity, as if their tumultuous romance had never been consummated during the unfettered years of war.

That the war was over, and things were to be different, was the largest truth in the house. The next was that nobody – apart from Rose – had much idea of what happened now. But for Riley and Nadine, one immediate shift was that the sexual liberties allowed by the possibility of imminent death had disappeared like a midsummer night’s dream. Their reborn chastity happened passively and without comment between them. This had seemed to each of them at the time a form of safety, but by their wedding night Riley had become hideously aware of it, and also of the fact that he did not know what his new wife was thinking on the subject. He recalled the letter she had sent him in 1915: ‘Riley, don’t you ever ever ever again not tell me what is going on with you …’ But saintly woman though she was – in fact because of her saintliness – he could not – and he was aware of the irony here – find the words.

Riley brought with him to Chester Square various accoutre-ments: his etched brass drinking straw made from a shell casing, a gift from Jarvis at the Queen’s Hospital Facial Injuries Unit; a rubber thing with a bulb, for squirting and rinsing; small sponges on sticks, for cleaning; mouthwashes of alcohol and peppermint. His pellets of morphine, carried with him in a little yellow tin which used to hold record-player needles, everywhere, always, just in case. In case of what? he thought. In case someone shoots my jaw off again?

Riley’s mouth had for so long been the territory first of bloody destruction, then of its complex rebuilding by surgery and medical men, that he had trouble seeing it as his at all. Eating was still difficult, and took a long time. Trying to chew was difficult, trying to swallow, trying not to choke, trying not to dribble, even though he couldn’t always tell that he was dribbling because his nerve endings could not be relied on to know where they were. Trying to cough, or stop coughing. Learning to live with somewhat undisciplined saliva and phlegm – though that had improved a lot, thank Christ – and to accept that even when he had learnt to live with it, other people would always find it disgusting. Learning to accept when Nadine passed him a handkerchief. Learning to accept endless generosity and inventiveness with soups and coddled eggs and milk puddings, fools and mousses and shape from Mrs Joyce, the cook: baby food,he’d thought, then get over it, and he was getting over it. He still did not care to eat with others. The embarrassment of some strangers, the inappropriate concern of others, Nadine’s careful developed calmness, all exhausted him, but worse in its way was his own requirement of himself that he calmly ignore the food that started bit by bit to reappear as the privations of rationing faded away – fragrant Sunday joints, the clean crunchy salads, the chokable pies, the sweet smells of potatoes frying in butter, chicken roasting, bread baking. At times he was afraid of his own breath, of stagnant saliva, of deadened unresponsive lips, of his medicalised mouth in the normal world. He would clean it fanatically; and he would lapse into silence, sometimes, for several days, knowing that speaking was exercising, and he should do it, as he should eat. At times, during the winter, after their reunion and before their wedding, he had not known what he had to offer her.

The rooms at Chester Square were graceful and quiet. Rose, tall kind Rose who had nursed him at the Queen’s, had set up a decanter of whisky and some cold supper in the drawing room.

‘Have a sandwich,’ he said to Nadine. Egg and cress,he thought. Rose made them specially because they’re soft. He knew it was courtesy and affection, but in his longing for normality he couldn’t help feeling it as controlling, as singling him out … Oh it’s not the kindness of Rose’s response that singles you out, Riley. It’s the damage itself. He was so grateful. He was getting tired of being grateful. But he was grateful.

Nadine, perched on the corner of a sofa half unfurled from its covering, took a little white triangle. He knew she didn’t like eating in front of him either, though he pretended he didn’t, hoping that she would get over it. It was another thing he had to be gracious about. They each drank a little whisky, and were silent. He was terribly happy. Look at her! With her yellow eyes and her sideways smile. But—

It is our wedding night. But—

He couldn’t – didn’t want to – put it into words. Oh the irony! If he could speak clearly, there would be no need to say anything! If my mouth was normal, I wouldn’t have to speak, I could just … act … He looked at her, and in his mind his look became a caress, a touch, an invitation, a demand … how could he follow up such a look? How could she respond to it? He looked away.

Nadine, as nervous as him, stood suddenly, and said, ‘Well!’ cheerfully, smiled at him, and started for the door. He stood too, wondering whether he would follow, or wait. He didn’t know. He went out into the hall and as she reached the landing she looked back at him, and said, briskly, ‘It doesn’t matter, you know.’

He, who knew her so well, did not know what she meant by it. It doesn’t matter? Of course it bloody matters.

She was off, almost scurrying, into the bedroom. So he went up, and stood in the doorway. She was further round, out of view, putting on a nightgown – a new one.

Then he was in the bathroom, trying to clean his mouth without disgusting illustrative noise, and his thoughts flooded in: We should have talked of it. I should have kissed her before this. I should have prepared – myself – her . . . But how could he kiss her? He had tried it out, on his own arm, like a youth. His lips had lain there, incompetent. He could not kiss her – not her mouth, her breast, nor any part of her. He could remember kissing her. It tormented him.

When he came back she was in bed, so he undressed. The previous times – before, during the war – they had blushed and fumbled and laughed and burned up and torn each other’s clothes off: the first time, in the field; the miraculous interlude in Victoria. He had never seen her in a nightgown before, in bed. His wife. Safe and sweet. Her hair had grown back a little over the winter, the wild dark curls starting to coil again. She’d brushed it.

She was smiling up at him – nervously? He didn’t want to make her nervous.

It was pretty clear to him that she couldn’t want him that way. Damaged as he was. How could she?

She was thinking: Why did I say that, on the landing? ‘It doesn’t matter?’ What doesn’t matter?

She’d felt foolish even before the words came out. She thought: I’m sure he would want me, if he was physically, um … She was thinking: I must not pressurise him … but he hasn’t – since – and he’s had so much morphine, over the past years … She didn’t know, actually, if he was still taking it. There were areas of his life where his independence and his privacy were so important to him, which was quite right. Quite right. She had been watching him, cautiously. He did not seem to see himself as a patient, or a cripple, and she was not going to tell him that he was. She didn’t know if he was or not. Even if she had an opinion, it was not her decision.

She had been thinking about this moment for weeks. Something would change, now they were married. The most important thing (which she had borne in mind all winter, and was, she felt, doing well at integrating) was that, specially as she had been a nurse, she absolutely must not become his nurse. But this vital consideration made it difficult for her to, for example, enquire about whether the morphine had affected his … Hm.

To be blunt …

She didn’t know if he would be physically capable. She didn’t know how to ask. Or if she wanted to ask. She hadn’t wanted to spoil anything by asking. They had always been so magically immediate with each other, understanding, catching eyes. Since they were children they’d had that! Apart from the one great stupid error, his attack of spurious honour, of over-gentlemanliness, when he’d told her he had a girl in France, when in fact there was no girl, it was that he hadn’t wanted to inflict his wounds on her – oh, Lord, the kindness he had meant by that, and the arrogance … Apart from that, that little thing,they’d never really had to ask, or explain, about anything. She didn’t want to ask now. She wanted the romantic. She wanted them to be magical, not to have to ask or explain. They had to be romantic. Because if they weren’t romantic, what were they? She was aware how their union could be seen. She was damned if she was going to be seen as his nurse, and him as some pathetic, incapacitated …

Stop it. Nobody thinks that. And who cares if they do?

And a woman is not meant to want it anyway …

Yes, but I’m not that kind of squashed, repressed Victorian woman – and I bet they did want it, they just didn’t dare say …

And …

He came back in his pyjama bottoms. His face, so extraordinary. His mouth. The beautiful upper lip, the battlefield below. The skin above smoothed ivory by morphine, the scars below carefully shaven, not hidden, not displayed, only the moustache worn a little long, like the hair of his head, so as not to frighten people too much. His beautiful grey eyes. Twenty-three years old, looking a hundred. She watched his arm reaching in the shadow to turn out the lamp: the long scar from the Somme streaked across the muscle, shining. The glow from the streetlight outside fell on his strong back, the shape of his shoulders, the curve of his spine. He reached for his pyjama top and she said, ‘Don’t.’ And saw him misunderstand it.

He pulled it up over his shoulders.

‘No,’ she said. ‘I didn’t mean …’ and as he came to lie by her she slid her arms inside the shirt, and he sighed.

And one thin layer of tension flew off him – but …

But what about my mouth? he thought. I don’t … She can’t …

They didn’t kiss. They lay entwined on the cool sheet. Awake. Unconsummated.

She doesn’t want it,he thought. I mustn’t.

He’s not … He can’t,she thought. And I can’t—

Well.

If that’s it …

I must respect that.

The proximity of flesh was irresistible. Riley bit his tongue, natural upper teeth to false lower, and rolled over, so his back was to her, so she would not notice.

Oh, she thought.

After quite a long time, they went to sleep.

The day after the wedding, they went to Nadine’s parents’ house on Bayswater Road. She had not been home since the end of the war. Not for Christmas. Not at all. She had written bland letters to her mother saying she was all right, and less bland ones to her father saying she would come soon, but the fog of shock and exhaustion in which they had been dwelling at that time had prevented her from properly recognising the cruelty of staying away. Neither she nor Riley had even told their parents where they were living. It had been part of the silent arrangement. Nothing, till spring. Just a suspension between past and present which allowed them to attend to neither.

They stood on the steps in the front garden, their backs to Kensington Gardens, the door shiny before them, and each gave the other a brave look as Riley rang the bell. Nadine took Riley’s hand, and he felt the flow of feeling shared and supported by the physical union: two bodies stronger than one, two hearts more capacious. Being – becoming – more than the sum of their parts.

A maid answered, and he wondered what had become of Barnes: perhaps he joined up after all. Perhaps he got killed. Or perhaps he got that guesthouse with Mrs Barnes. Let’s hope so. It’s been six months since the end.

Lady Waveney was home, and Sir Robert too, the maid said, Who could she say was calling?

‘I’m Nadine,’ said Nadine, and the girl blinked, and said: ‘Oh! She’s in there, Miss …’, and stared: the prodigal daughter returning, and with a wounded officer …

Riley knew the look, and what it meant: Oh my word, oh poor thing, such nice eyes, and it’s not right to stare, but how can she bear him? He didn’t stare back at the maid. And when he and his bride went into the beautiful, unchanged, unforgotten drawing room, all velvets and spring light and rather good paintings, he allowed his new mother-in-law a few moments, too, to look at his face, before he looked up at hers. His determination and habit was to wear his scars without apology but with kindness. The last time they had met (Jacqueline, Lady Waveney, what was he meant to call her?), he had had only his scar from Loos, the little dashing cut on his cheekbone, the clean, romantic, officer-in-a-duel-of-honour scar. So he would be a shock, with his reconstructed jaw, his twisted mouth, his slightly too-long hair lying only slightly effectively over the scars where the skin flaps had been taken from his scalp and brought down to cover his new chin. He was beginning to realise that he did not know what he looked like to anyone else. People said his surgeon, Major Gillies, had done a good job, and Major Gillies himself said it had healed well, and Riley chose to believe this was true. It would have been unhelpful to do otherwise. However. He had learnt that he had to be patient, and allow everyone who saw him their own response, and if necessary lead them through their shock and doubt to the fact that he had accepted his lot. This despite the fact that his speech was not entirely clear. Oh, and he had to let them understand that unclear speech did not equate to an unclear mind. This too was turning out to be part of his responsibility, every time he spoke to someone new. Or, indeed, someone from before. He hadn’t on the whole been meeting new people.

Jacqueline, wearing a luxurious old-fashioned kind of house-gown, her red hair piled up, was doing something with a plant by the long window at the back of the drawing room. She turned, and blinked three times. Once to see her daughter. Once to see her with Riley Purefoy. Once to see Riley Purefoy’s face. Then she lifted her hands – to open her arms? For an embrace? Riley couldn’t tell. It turned somehow into a shrug, which was visibly not what she had meant. She put down her secateurs.

‘Oh my dear,’ she said. ‘Oh my dear.’

‘Hello, Mother,’ said Nadine.

Neither of them advanced across the blocked-out distance between them. They seemed to him to be suspended. So he stepped forward, held out his hand to Jacqueline, and said, in his odd, quiet, bold voice, mangled a little through the straitened mouth: ‘Lady Waveney – I am pleased to see you. You look well.’

‘Captain Purefoy,’ she said, nothing more than another blink betraying any response. He was impressed.

‘Mr, I think, by now,’ he said.

‘Oh no,’ she said, with a little passion in her voice. ‘Always Captain. Always. Will you have tea?’

‘Thank you, Mother,’ said Nadine. ‘We will.’

The ‘we’ stopped Jacqueline in her movement towards the bell. She turned, looked, saw: gold ring.

‘Is Sir Robert at home?’ Riley said gently. ‘I need to speak to him. I have left it rather late already …’

‘So you have,’ said Jacqueline. She raised her eyes to stare at him, at her daughter, at him again. No one dropped from anyone else’s look.

‘Well, I …’ said Jacqueline.

Riley observed: Jacqueline covering shock with bred-in-the-bone manners, the calmly beautiful half-smile she wore whenever she didn’t know what to do. Nadine, still in her mother’s presence feeling thirteen years old, naughty, resentful and blank. He saw the careful breath with which Nadine prepared to start the speech she had for her mother.

‘I’ll just call your father,’ Jacqueline interrupted, undercutting her daughter at just the most effective moment. She crossed to ring the bell. The maid, standing agog in the hall, stepped into the room. ‘Call Sir Robert, Mary.’

And Nadine instead burst out: ‘I do hope, Mother, that you’re not going to make some stupid fuss about this, because it’s done, it’s right, and with or without your blessing Riley and I are—’

My brave fighting girl, he thought.

‘Oh no,’ said Jacqueline faintly. ‘My dear. No.’

Nadine fell silent. Her mother looked, in a way, as if she was thinking about something else entirely. Silence drifted round the lovely room; the pale panelling, the dark velvets, the sea colours, the windows full of leaves and light.

What does she mean by that? No, what?

‘So, have we your blessing?’ Riley asked, cautiously. He was fairly sure that was not what she had meant.

Jacqueline looked up. ‘I invited you in here, Riley, all those years ago. Me. I thought you were sweet. I thought you needed drying off and feeding, and you responded, and look at you now. Look what you have made of being knocked into the Round Pond.’

He said nothing. It was not clear whether this was sneering or admiration. Or both.

‘You are an astonishing boy.’

He hadn’t been called a boy in a long time. Ah – it makes her feel better about me. As if I’m not a man, and I haven’t – ah—

Well, madam, you’re closer than you know.

Sir Robert came down the stairs: a clattering, hurrying step, and a figure at the door.

‘What’s going on, my dear?’ he said, before he saw: and when he did the joy in his face was heart-melting, immediate, irresistible. There was no difficulty here. Riley wondered how much it hurt Jacqueline to see the bare-faced love Nadine gave her father, running to him, burying herself in him, visibly radiating the joy she took in the fatherly smell of him; his inky fingers, greyer hair, familiar voice. He held her away to look at her, held her back to his chest to embrace her, held her away again to admire her – and noticed Riley.

‘Purefoy!’ he exclaimed. ‘You cuckoo! Where’ve you been? Good Lord – excuse me, darling – my word.’ He stared, for a moment only, at the face, then gave a tiny sigh and a shake of the head. ‘Well, Purefoy—’ he said, and he strode over, attempted to shake hands, and couldn’t stop himself from embracing.

‘It seems—’ said Jacqueline, with a slightly twisted smile, but Riley broke in and said: ‘Might I have a word with you, sir? In private?’ So little had been correctly done. He would do it correctly. As far as possible.

Sir Robert couldn’t make out what Riley was saying. Riley repeated it.

‘Modern world, Purefoy,’ said Sir Robert, getting the words, but not the purpose of them. ‘No secrets here …’ But he sensed there was something, so he allowed himself to be manoeuvred out of the room, into the hall. The maid skittered from under their feet, and there they foundered for a moment. Riley did not know where to go. The library, he felt, from novels, was the correct location. There was no library.

‘What is it?’ Sir Robert said. ‘What’s on your mind that the ladies can’t hear?’

Riley grinned his sideways grin. No excuses. No avoidance. No modifying his vocabulary even. Get it done.

He wanted to say that he had a post facto request, but he knew he would not be able to get it out clearly.

‘The horse has bolted, sir,’ he said. ‘I. I. I. Wanted to ask.’

This was hard. All right. Pretend he’s a senior officer. All right. Robert was looking curious, and civil.

‘For Nadine’s hand. To marry her, sir. But. We’re married already.’ Pause. All right. Off we go.Long sentence coming up. ‘Yesterday, sir, without your permission, because if anything had prevented our marrying now, we might not have been able to bear it, sir.’

Sir Robert was concentrating to make out the words, and utterly taken aback – silent – and then: ‘You cheeky little …’ he said. ‘You – it’s not even wartime! Explain yourself, man. Does Jacqueline know about this?’

‘Only just,’ said Riley.

Sir Robert stared at him. ‘Oh, good God,’ he said. ‘What on earth? What am I meant to – have you any money?’ he said. ‘To marry on?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Prospects?’

‘Far from it, sir, as you know.’

‘Dependants?’

‘I hope to have, in due course.’

‘And, er, this?’ Robert gestured to Riley’s face. ‘What about this? I mean – oh, good God.’ The ramifications were filtering through. Wounded, disfigured, penniless, war hero, fait accompli, cheeky sod, bright though, common as muck, his family – good people though, decent working people – and that face, that voice. Oh, good God. What a bloody cocktail.

‘She doesn’t mind it, sir. So I can hardly complain.’

‘Passchendaele, wasn’t it?’ Robert said.

‘Yes, sir.’

Silence.

‘Hmm.’

What a bloody cocktail.

‘So what are you doing with yourself? What are you going to do?’

‘Thinking of Parliament, sir.’

‘What!’

‘The Labour Party, sir.’

‘Are you a Communist, Purefoy?’

An echo of someone else asking him that years ago passed through his mind … Peter. That dugout on the Salient, a conversation about music, the first human look you’d had in months – 1916?

‘No sir,’ Riley said. ‘But I’ve become attached to notions of peace and justice. I believe they’re worth working for.’

‘Good Lord – you didn’t stand, did you?’

‘The election came a bit quick.’

‘Good God.’

Riley stared at him, waiting. Calm, strong.

Sir Robert stared back, ran a hand over his face, and then said: ‘Let’s join the ladies, shall we?’

They could all see by Jacqueline’s still, polite expression, that she was too surprised to know what to think.

‘Riley,’ Sir Robert said. ‘Nadine. You leave us no choice. We are not the kind of people who turn their daughter away – as you should bloody well know – sorry, darling.’

Relief?

He continued: ‘Though you could’ve given us the chance to, well, discuss it, and demonstrate our … spontaneously, if you see what I mean … so we could give our blessing in a more organised fashion …’

‘We didn’t choose,’ Nadine said gently. ‘We had no choice. It was a fact …’

‘I dare say,’ her father said. ‘Of course. And so …’

Jacqueline was staring. ‘Don’t you dare,’ she interrupted. ‘Robert? This is outrageous.’

‘Well …’ he was saying, and Riley could almost see the cold drifting down through Nadine’s limbs.

‘Outrageous,’ said Jacqueline. ‘Unforgivable.’

Riley dipped his head, and took Nadine’s arm into his.

Robert glanced from him to Jacqueline and back. ‘Oh,’ he said. Nadine was frozen.

‘I’m sorry,’ said Robert.

‘They should be sorry,’ Jacqueline said. ‘Well – they will be, won’t they? A silly girl and a boy who doesn’t know his place. How ridiculous.’

Riley saw his new mother-in-law’s short breath, and the high triangles of pink on her cheeks. Somewhere, he felt pity and it warmed him through the horrible little silence that sat on the room. Silence can mean so many things. His arm was firm under Nadine’s hand as she let go of it.

‘Well, never mind. Goodbye, Daddy,’ she said, and leant in to give him a kiss. ‘Goodbye, Mother’ – from a safe distance. ‘Don’t worry. As the war’s over, we’ll probably all survive long enough for you to indulge your little fit of pique.’

‘Darling girl,’ Robert said.

‘We’ll see you soon,’ she said, and blew him a kiss on the end of her finger.

Riley watched her: My lovely, beautiful fighting girl.

As soon as they were out of the house she took Riley’s arm again, and held on to it.

‘You up for the next round?’ he asked, and she nodded tightly as they walked.

Walking up the street towards Paddington, his family, his childhood, a cloudy shame rose in Riley. Yes, he had every excuse under the sun, but he had neglected them. One afternoon in 1917 his mother had burst into the ward and not recognised him and shrieked and collapsed at the sight of his fellow patients; just before Christmas last year he had arrived out of the blue and stayed for fifteen minutes. Other than that, he had not seen any of them. You could have handled it better,said one little voice; you did yourbest, said another. Anyway. Now was the time for putting things right.

Up towards the canal, they turned into the little terrace of little houses.

As they came up to the door he could see his mother from the street, scrubbing the inside of the front windows with newspaper. She would have dipped it in vinegar. He remembered the smell. She did it every week; so near the station, things got dirty quickly. A figure moved behind her: Dad.

Riley squeezed Nadine’s hand, and knocked.

A moment or two passed before Bethan opened it. He knew she had been hiding the newspaper wads and taking off her apron.

‘Hello Mum,’ he said, apologetically, and she squeaked, and put her hand to her mouth, and called, ‘John! John!’ And his father came, and dragged him in, and he said: ‘Dad – Mum—’ and though his plan had been just to blurt it out, quick and straight, he found he couldn’t speak at all, so he sat at the kitchen table, and Bethan put the kettle on the hob, and John came through, and looked at him, and patted his shoulders, and said, ‘My boy.’

‘There’s a woman outside in the street, just standing,’ announced a girl, popping round the kitchen door – and, seeing the man at the table: ‘Oh my word, what’s this?’

Riley looked up. Looked down again. Looked up, and laughed. Wispy, pert, blonde, mouthy.

‘Elen?’ he said.

Her face went very wobbly.

‘You look exactly the same,’ he said.

‘Well you don’t,’ she said. ‘What the hell happened to you?’

‘Kaiser Bill stole my jawbone,’ he said, and stood, and smiled, but she pushed past him saying: ‘Excuse me. Four-and-a-half years, Riley. Four-and-a-half years and … three postcards … and a promise of a teddy bear. The war ended last November, or didn’t you notice?’

‘Elen,’ said John. ‘Mind your lip.’

‘I’m right though, ain’t I?’ she said. ‘It’s not fair on Mum. Well I suppose I’m glad you’re back. You are back? Merry! Merry?’

Merry was in the doorway, staring. The little room was already crowded now. How am I going to fit Nadine in here? Merry was darker, heavier built, more guarded. She stared at him.

‘Here’s Riley!’ said Bethan, encouragingly. They were all in a sudden parabola of cross-currents. So many emotions. Riley felt unsteady. He should have written. It wasn’t fair on them. Sunday afternoon.

‘How do you do,’ said Merry, and Riley flinched. She’d been eight when he left. Both girls were looking at his scars.

‘Yeah, Mum said your jaw was blown off,’ said Elen brutally. ‘That a new one, then?’

‘Yes,’ he said.

‘Fancy,’ said Elen.

‘Make the tea, Elen,’ said John. ‘You all right with tea, son?’

Riley took his brass straw from his pocket, and twirled it sadly at his father. Merry stared at it.

Elen poured the boiling water, and plonked the pot on the table. ‘Well, thanks for turning up, Riley. I’m back off now, Mum. See you next Sunday, same as usual.’

‘Elen,’ said Riley and Bethan.

Elen’s mouth was white as she swept past. Merry hopped out of her way.

‘Elen,’ Riley said again, and turned to follow her. Bethan put her hand on his arm. They both heard Elen say, at the front door, ‘You might as well go in. I don’t know why he’s bothering to be tactful.’

Merry was still staring when Nadine appeared in the kitchen doorway, and said, ‘Hello,’ quietly.

‘Miss Nadine!’ cried Bethan, and John shot Riley a look, and Riley took a big breath before stepping to her side, past the chair and the coal scuttle and Merry. Quick to the kill, quick to the kill.

‘Mum,’ he said. ‘Dad. Nadine and I are married.’

It was Merry’s face his eyes landed on. Big tears were on her young cheeks.

‘Oh, Merry,’ he said. ‘Oh, Merry.’

Silence drifted, pulled and swung between them all. Then Bethan said: ‘We would have liked to have been informed.’

John held his hand out to Nadine. ‘Married,’ he said. ‘You married our boy? Well. Well. Good for you, Miss.’

‘I know it’s all odd,’ Nadine said. ‘Please call me Nadine. I think that will make it less odd. Please.’

Bethan gave a kind of roll back on her heels, a surveying look with a chin lift, which said, ‘so that’s how it’s going to be’.

‘It’s all right, Ma,’ Riley said. ‘We were afraid of a fuss. That’s all. We didn’t even want a wedding. We just wanted to be married.’

‘All your worldly goods, eh, Miss?’ said Bethan. ‘There’s nice.’

‘I don’t have much,’ said Nadine, and got a withering look.

‘Who’s going to wear the trousers, if you’re to be a kept man, Riley?’

‘Mum!’

‘Wounded hero only lasts so long. What about when you’re just a sick, ugly man with no money? Where are you going to find a job to keep her? No offence, Miss Nadine, and I’ve always liked you well enough.’

‘None taken, Mrs Purefoy,’ said Nadine, mortified. ‘I like you well enough too. Riley, should we give them a little time to get used to it, perhaps?’

Bethan was grinning. Riley saw her waiting for him to agree to Nadine’s suggestion. She has cast it now that any time I agree with my wife, I am less than a man. And any time I disagree with my wife, she can say, ‘I told you so.’

‘Mum,’ he said. ‘Don’t be foolish over this. Had to happen one day, eh? Dad?’

‘Come round for Sunday lunch next week,’ John said. ‘They’ll calm down. Congratulations, son.’

Riley thanked him. It was all so quick.

Merry was still crying. Riley said to her: ‘I’m sorry for being such a bad brother. I’ll be a better one.’

Merry said: ‘Are you my brother?’

They crossed into Kensington Gardens, holding hands, walking into the green. Up the Broad Walk, beyond the Orangery, the pleated new leaves of the arcaded hornbeams gleamed in the sunlight like Venetian glass. Through the observation windows in the hedge they caught sight of the Sunken Garden, terracing down geometrically, with its long pond and lead planters.

‘Our mothers are afraid for us,’ he said. ‘That’s all.’ He could understand the fear without feeling any obligation either to adopt it himself, or to try to make the situation more acceptable to them.

Nadine said: ‘If they haven’t the sense and courage to look at us and give us every bit of loving support in the world, then they can go to the devil.’ She glanced up, as if to check. ‘I shall feel nothing but relief,’ she said, ‘that I don’t have to deal with them.’ She was wearing that green wool dress of Julia’s, too hot for the day, but she had been living in uniform for so long she had no clothes of her own, and during the long, quiet hibernation at Locke Hill, she had made none nor bought any. With Julia still hardly leaving her bedroom it made sense for Nadine to borrow her clothes. She was still wearing the high lace-up boots, and the cap. Riley had a surging feeling of freedom at the idea that she might now acquire some clothes. He wanted to kiss her. Will my desire for her fade? he wondered. How long am I to live with this?

They stayed in the gardens late, wandering, sitting on benches, talking mildly.

The irony was that what Jacqueline and Bethan were scared of was true. The surface of society had been blown around by the war, but had the architecture changed? Were things going to be different now? Where would a Riley, married to a Nadine, fit in? If Nadine were straightforwardly posh, and he straightforwardly a working man, might it be simpler – if only simply more impossible? But she is half-foreign and artistic,he thought, and I am a semi-educated semi-adopted cuckoo in the nest. And my face reminds everyone every moment of what I have given for them, and of what they want to forget about now. And don’t we all …

They had arranged for two rooms in Chelsea, and they would work. They had considered education: they both half felt they wanted more of it, and concluded that at twenty-three they were too old, and then doubted their conclusion. Certainly, no one was ‘going back’ to anything. They weren’t mourning some pre-war Utopia, the golden years before the Titanic sank and Captain Scott died on the ice and the Empire and Ireland started to bite back. For Riley and for Nadine, looking back would involve unbearable regret about what might have been. Unbearable. So there was nothing to go back to.

And the war was still over.

Nadine said, as they wandered over to the Round Pond: ‘We’ll have to take ourselves outside all that and create our own new world. Chelsea will be the start …’

She said, as well, ‘You seem to feel you need to justify your existence, but you don’t.’ And he replied: ‘Yes, I do. I don’t know why, but I do.’

And she said: ‘Take your time. We have time now …’

‘I don’t want to take time. I want – I want—!’ He’d been stuck for too long, resting, recovering, receiving, disengaged. ‘We’re not going to be living off your parents, at twenty-four. I’ll be doing something.’

‘It does seem ridiculous that just because your wound is in your head, you get no pension for it …’ she said. ‘When if it had been a toe, even—’ She stopped. They’d said this before. It annoyed him. And it was his territory.

‘It makes sense,’ he said. ‘They only needed our bodies to follow orders. They didn’t value our heads then; why should they value them now?’

She laughed.

By the time the keeper called for closing, the damp, growing, evening smell of the park was rising around them: moss, tubers, lilac, hyacinths. At Locke Hill, during the half-paralysed, shattered, Rip-Van-Winkled winter, Nadine had marked the days of emergence from hibernation by drawing each flower as it appeared from black earth and mossy branches, marking the way to spring: snowdrops, aconites, crocuses, scilla, stars of Bethlehem, grape hyacinths, daffodils; camellias, almond blossom, cherry blossom, pear and apple blossom. Harker, the silent, ancient gardener, would quietly nudge her towards each new arrival. It seemed like progress, of a sort.

They were restless. The marriage rooted them to each other, but everything else was still nebulous and reverberating.

‘Perhaps our brains are still shaking,’ she said. ‘I still feel jumpy. It’s too soon to settle.’

‘I’ve heard that it takes as long to get over something as you spent in the something you’re trying to get over,’ he said. ‘Makes a kind of sense.’

She smiled at his beautiful face. ‘That’s good,’ she said. ‘So we’ve got till, say, 1923. Barring future crises.’

‘1923! Where will we be then?’

‘One thing at a time,’ she said. ‘Honeymoon first.’

Honeymoon.

And that night, rattling in the separate couchettes, which gave an excuse for not thinking about that, for the moment, on the train to Paris, he couldn’t stop thinking about decisions, and the future, about how strange it was to be able to think about those things. There was going to be a future. He looked towards it, consciously, turning his mind away from the past the way a car’s lamps turn at a junction: illuminating possibilities, the road ahead, with beams of light that do not, cannot, show everything. As the car turns the lights are only ever shining straight on, out over – what? Another path, a path you won’t take and can’t know, that you glimpse in passing. It’s the future, it’s forward, but what forward entails, you can’t know. It’s shocking enough for now, after those years of orders and terror and imminent death, that forward even exists. He and Nadine had a forward to go into. They had choices. They had decisions to make. They had a degree of power. It was quite peculiar.

He was hideously aware of her, lying beneath him, separated by the padded wooden shelf he lay on, rattled and thrown around by the train.

Chapter Two (#ulink_b6ae7249-48f4-52af-a7fe-2ebe64c98ea9)

Locke Hill, Sidcup, March–April 1919

After the wedding Peter, Tom and Rose returned to Locke Hill. Max the red setter ran up, tail floating, and put his nose in Tom’s face. Tom stood on the drive while his father opened the front door; then he stood in the hall, by a jug of white jonquils, while Peter, tall, slender, still in his overcoat, hurried through to his study. He watched Julia, his mother, shimmy down the stairs and across the hall.

‘Darling!’ she cried, to Peter’s back. ‘It’s roast beef! What luxury! Will you eat with us? Or – I suppose you’re tired – Mrs Joyce has made Yorkshire pudding?’

She stopped at the dark, polished door of his study, which had fallen shut. All was silent.

‘I could bring your tray,’ she said. She was wearing lipstick. Tom watched her. He was nearly three years old and had been living with his grandmother and the nursemaid Margaret in another house; he didn’t know why. At Christmas he had been brought here; he didn’t know why. Now Eliza looked after him, and everything he wanted and needed was in the power of this Mummy and this Daddy, who he didn’t know, but who he understood were the important ones.

He went and stood by Julia, uncertainly.

‘Or if you prefer I could coddle you an egg …’ Julia called gaily, fresh and nervous. ‘Or …’ Her chalk-white face stretched immobile and expressionless, and her blue eyes shone, wide and terrified. Tom didn’t know why her face didn’t move the way other faces did.

The jonquils smelt beautiful. All winter Julia had been bringing up hyacinth bulbs in glass jars from the cellar – ‘heavenly smell, isn’t it?’ – or finding the first narcissi, or a sprig of early blossom from the orchard wall, and taking them in to Peter. Occasionally Tom, imitating her, would take a flower, and give it to Julia, or Nadine. They would say, ‘Thank you, darling.’

Nadine had not come back after the wedding. Tom had not known why she and Riley were living in his father’s house in the first place, any more than he knew why he had not been, or why Nadine and Riley had not come back. He did not know what the war was, nor how even if people had a home they did not always feel capable of going there. Of the webs that had bound these adults together over the past years he knew nothing. That his father had been Riley’s commanding officer; that Riley had carried his father back from No Man’s Land; that Rose had nursed Riley; that Riley had deserted Nadine; that Julia had comforted Nadine and offered her a home. He knew that they were tangled up with each other, but he knew only with a child’s aeonic instincts, not as information.

And he knew that though Julia was called Mummy and smelt right, she behaved wrong, and so it was best to go and sit with whoever was consistently kind. That was Nadine. He had liked to sit curled up against her, and when Riley came to sit there too, he didn’t make Tom go away.

Riley’s face had something in common with Julia’s, this much Tom saw, in that neither face moved with ease. But few faces were easy to read. His father’s eyes were pale and rich, grey-shadowed, with most to give and most to lose. They switched on and off like a lamp; you wanted their kind look, but you couldn’t trust it at all. Mrs Joyce, the cook-housekeeper, had an occasional expression of concentration it would be foolhardy to approach. Eliza, his nursemaid, had a sleepy, empty face. But his mother’s eyes lied like the tiny waves on the beach washing in four different directions, her skin made no sense, and her eyebrows were not made of hair but of tiny painted strokes which did not come off. He’d tried, once, with a hanky and lick, like his grandmother used to do to his cheeks when they were going somewhere. His mother had brushed him off. Nadine’s face was easiest: it had a warmth which Tom liked looking at. And so he was sad that she had not returned.

Julia’s sufferings during the war had been extreme, and exacerbated by the fact that from the outside they seemed the result of folly and vanity. Throughout those years she had tried to maintain her marriage by investing in the only thing about herself which had ever been valued by others: her blonde and luxuriant beauty. During that time Julia’s mother had taken Tom away, ‘for his own good’. By the end, lonely, neurotic, deserted, Julia had become unbalanced, and had inflicted on herself a misconceived chemical facial treatment, which she had deluded herself into believing would ensure her husband’s happiness. This had stripped and flayed her complexion into a scarlet fury, making it frightening and unreadable to a child – to her child, when he was brought back. He was scared of her, and she was scared of him. Now, by spring, her face had faded to a streaked waxy pallor. It was not unlike the make-up the girls in town were wearing, and the ghost of beauty appeared unreliably in her bones and in the smoothness. Meanwhile her painted mouth uttered the over-emphasised banalities with which she tried to make up for … everything. Her blue eyes shone wide and terrified. She had spent four years of war preparing for her husband’s return; four years of concentrated compacted nervous obsession with loveliness, comfort and order, for his benefit. She had utterly failed.

Even now she tried to give him treats all the time, like a cat dragging in dead bird after dead bird, laying them at the feet of an indifferent Caesar. The flowers. Dressing too smart for dinner at home. Snatching cushions out from behind his head to plump them up and make him ‘more comfortable’. He was not comfortable.

There was a fire in the sitting room. Tom went in there, and sat on the edge of the pale sofa where Riley and Nadine had usually sat. By habit he did not go on it, because he wanted it to be free for either of them. But they were gone now.

Until Christmas, when Riley and Peter had turned up unannounced in the middle of the night, Tom had not known any men. He was unaccustomed to affection, and at his grandmother’s house had sat quiet and dull with a wooden horse or a train, as instructed by whichever woman was in charge of him. When the grandmother had brought him to this house, and this father had appeared, at Christmas, Tom had felt a great and important slippage of relief inside himself: here it was, what had been missing. That the father periodically disappeared again, into the study, was not ideal, but Tom was a patient boy. The father was there. And Riley. Tom had lined up with these new people, the men, and Nadine, and Cousin Rose, as if they must be more reliable, kinder and stronger than the women he’d known so far. In this full house, he hoped he would find what had been missing.

Julia came in and held out her hand. Tom stood as he had been taught, and took it. She whispered down to him: ‘Come on, darling, let’s go and see if Daddy will come out and eat with us.’

Tom did not want to go. Daddy did not want anyone. That was why he had gone into his study. He didn’t know why Mummy didn’t understand something so simple. He wished Mummy would go behind her polished door, so that he, in the absence of Riley and Nadine, could go and sit in Max’s basket with him.

They approached the study. Julia smiled down at Tom as she knocked on the door. There was no response.

‘Well!’ she said and, almost shamed, she opened it.

Peter was sitting in his armchair, an old leathery thing, shiny with the polishing of ancestral buttocks in ancient tweed. He’d lit the lamp and was reading the paper, his long fingers holding the pages up and open. There was no fire, and the whisky glass beside him was already smeared.

‘Darling?’ she said.

‘Which darling?’ he said, not looking up.

‘You!’ she said. ‘Of course.’

‘Oh! I couldn’t tell. You call everybody darling.’ He moved the paper half an inch and glanced at her. ‘Well?’ he said, glittering.

She dropped Tom’s hand, and went away. The door swung shut behind her and so Tom stood there until Peter called him over, ruffled his white-blond hair and, finally, said, ‘Run along, old chap.’

Most days Julia worked herself up to try again.

‘Peter?’

A grunt.

‘There’s one thing I’ve been wondering about.’

A further, more defensive grunt.

‘It’s—’ from Julia, and at the same time from Peter: ‘Well, whatever it is, I’m sure it’s my fault.’

‘I wasn’t thinking about anything being … fault,’ she said.

Silence.

He had not looked up. It wasn’t the paper now, it was Homer. What might that mean? Why would he prefer to sit and read all day instead of being with us? Or going to the office like a proper man? It’s not as if he hasn’t read the Odyssey before …

His hair is looking thin.

He’s only thirty-three.

She let out a quick, exasperated sigh.

‘Peter darling, please listen to me.’

He turned, put down his book, looked up, and said, coldly and politely, with no tone of query in his voice, ‘What.’

Oh Peter!

‘I just want to know what happened!’ she burst out. ‘What happened to you?’

‘What happened?’ he said. He gave a little laugh of surprise. ‘Why, my dear, the Great War happened. Have you not heard about it? You might look it up. The Great War. The clue’s in the name. Now go away.’

She swallowed.

She still tuned his cello most days. He hadn’t looked at it since he’d been back. But he might.

He used to sing and make up little songs all the time. All the time! It was so sweet.

A few days later Julia knocked on Peter’s door again.

Go away,he thought. Go away.

‘What I was wondering,’ she said, loitering in his doorway, neither in nor out, ‘no, don’t say anything, please – I just … wanted to know what you thought.’

‘About?’ Peter said. He didn’t look up. Not out of unkindness, or lack of concern, but out of inability. Julia’s desperate goodwill tormented him – these constant interruptions – and then he was so foul to her – and her face – expressionless, taut, inhuman almost with those terribly human eyes glowing out – her face was a perpetual reproach. Look at her, he thought, though he couldn’t look at her.

‘I was wondering,’ she was saying, ‘about before the war …’

He raised his head and stared at her like a hyena about to howl.

‘Why on earth would you do that?’ he said.

‘I’m trying to remember whether we were ever happy.’

You want to remember happiness? Jesus Christ, woman, if one remembers happiness—

‘And whether my love for you is based on anything. I can’t remember. It’s been so long. I want to know. Because I think perhaps we were.’

Oh, God.

‘So what?’ he said, bewildered. ‘That’s the past. It’s dead.’ And – Ha! What a great big lie that is! he thought. If only it were dead. But it’s not even past. The past visited him most nights. Wandering about the wide gates and the hall of death, like Patroclus … She is no doubt thinking about some other past.

‘We were happy,’ she said, stubbornly. ‘We were happy in Venice, and we were happy that night at the Marsham-Townsends’, when we walked by the tennis court … my twenty-fifth birthday. And I was happy when you proposed to me …’

He lifted his mind. He had been thinking about the Trojan War; specifically about when mighty Achilles’ beloved friend Patroclus was killed in battle; about Achilles’ grief, how he locked himself away in his tent, went rather mad really, seeing ghosts and so on. He cut all his hair off, even though he’d promised it to a river god in exchange for a safe return home after the war. He’d refused to fight, though he was the greatest of the Greek heroes, and without him to lead them, the entire army lost faith, and every man in it was at risk. It was as if he no longer cared for his country, or for his leaders, or for his fellow soldiers – he only cared for his one friend. Peter had been thinking, is there an inherent contradiction in hating war and honouring soldiers? And then his mind had flung him back into thinking about soldiers. Dead ones. Loos and the Somme.

So with considerable effort, and for her sake, he lifted his mind from all that, and manoeuvred it round to Venice, and that night at the Marsham-Townsends’, and when he proposed to her. He remembered, for a moment, speaking to her appalling mother, and wondering what her father had been like. He tried to remember why he had proposed to her. Because we danced so well together – was that all? No. Because she was so beautiful? Yes – and … because she was so nice. She was soft, and gave kind advice. I was always pleased to see her when I turned up somewhere, and she was there. She was kind when my father died. All very straightforward, really. And I felt very tall with her on my arm.

All right, then. Yes, back in Arcadia, we were happy.

And at the thought of happiness, remembered happiness, his mind panicked and scattered: pure fear. He closed his eyes, clenched his mind, to hold on.

Hold on to your mind,he whispered to himself. Hold on. You’re tied to the mast. All right.

All right.

Now say something nice to the poor woman. Go on.

He couldn’t.

Julia tried to remember herself before she knew him. Desperate to please, obedient, bossed and squashed by her mother at every turn, her dear dad only a memory. She had realised the game early: the sweeter and prettier she was, the nicer people were to her.

And then there was Peter. How glad she had been to run to him, his amusement, his kindness.

To her, that night at the Marsham-Townsends’ sprang out, glistening with verisimilitude. She smelt the orange-flower water, saw the sheen of starch on the gentlemen’s shirt fronts, heard the waltz, felt the brush even of the palm-frond against her bare white shoulder and her skirts swirling at her ankles, as Peter wheeled her out on to the terrace, whispering – what had he whispered? Something mischievous.

Her mother had been delighted to give her to a man with a big house.

After they were married he’d said: ‘Let’s not have children immediately. Let’s run around and have some fun first.’ She had no idea there could be any choice – she’d known nothing about anything loving, about being on the same side with someone, and being happy together. Then suddenly there it was: she and Peter, together. Yes, happy!

He caught sight of her by the mirror in the hall. She was glancing at herself as he glanced at her. Her eyes fell away from her own taut reflection.

She did that,he thought, to her own face, to be more beautiful, because she thought I loved her for her beauty. She thought it would help. She thought that I, while fighting the bloody war, losing men, Atkins Lovall Bloom Jones oh stop it STOP IT – was most bothered by some idea that my beautiful wife was not beautiful enough. Somehow, apparently, evidently, I let her think that. Though, dear God, I do not understand why anybody would think that washing their face in carbolic acid was going to help anything. But – bad husband – I failed to protect her from this bizarre idiocy of her own. Just as I failed – bad soldier – to protect my men. Both at home and at the Front, I failed. And I wonder if anybody else on this earth can see that she is a casualty of that war just as much as Riley, or me …

The next time she came to lean against his door jamb, he got in first. He pulled his jacket around him, pursed his mouth against the shallow pattering of his heart, and said: ‘None of this is your fault.’

Think about her. Hold on to that. Poor Julia. Really. Poor tiresome bloody woman. ‘I don’t know why you put up with me,’ he said. And I don’t. You don’t have the first idea why I behave so bloody badly. ‘You’ve always done everything you should.’

He looked at her – eyes only, not turning his head – and he saw that she was, with a hopeless inevitability, taking these unexpected kind words at face value and investing them with huge meaning.

Oh, God.

She burst into tears.

Say something.

Not ‘fuck off’. Don’t say that.

‘Oh, Julia,’ he said, trying to buy time, to hold his mind, to make it all go away. ‘I think it’s probably too late for us. I’m an awful crock. But,’ – and here, desperate, he said the only thing which ever stopped her from looking so bloody tragic all the time – ‘I could perhaps not drink so much.’

‘I would like that,’ she said, and he saw the sudden whirling desperate hope erupting inside her. It filled him with despair.

Jesus Christ, Julia,he thought. I will never make you happy. You never will be happy! You’ve ruined your famous beauty, for me – poor fool! I’m a lush and no one else will want you. There is no chance for you now, shackled to me. And yet look at you, all hopeful – dear God, what a woman – let’s make you smile. Perhaps I can make you smile …

‘Well, I’ll give it a go,’ he said. ‘Perhaps I might – should I? Go to one of those places.’ I could do that. Could I? His heart was still going in that sick-making way – too quick and light, and all over the place.

‘Oh, please!’ she cried, too keenly. Clearly she had been about to say, ‘Oh no, of course not!’when she thought: Yes! Grab the chance!

She’s awfully keen to be rid of me,he thought. And who can blame her?

And I’ve overdone it. I can’t do that.

But she was smiling at him, limp and tearful. ‘Oh, darling,’ she said, and corrected herself, quickly: ‘Oh, Peter.’

She looks happy. Dear God, I’ve made her happy! It’s so easy. But I can only do it by lying.

So lie. You owe her that.

Anyway, you lie to yourself all the time.

She was saying she would find someone, she would ask Rose, she was certain things could be better, she was so glad. She jumped up and went off to get on with it all.

Oh, Jesus.

In the course of the rest of the day he drank almost half a bottle of whisky and two bottles of wine. ‘Final fling,’ he said cheerfully. Julia beamed at him, the tight smile of her skin lit from within by a genuine if bewildered hope.

Keep away from me,he thought. Just keep away from me.

Chapter Three (#ulink_2c30910e-cee1-5b4e-9979-5e5c78e1dbc8)

Locke Hill, March–April 1919

To Rose it looked nothing like a fling. It looked like desperate unhappiness, i.e. business as usual.

The newlyweds heading off into eternal nuptial joy meant that Rose was now on her own with the two ghouls, the two fluttering, ragged banners gloriously emblazoned, in Rose’s eyes, with her failure to save them. Peter and Julia lurched through her days and tagged across her mind, united in bitterness, loss and the seeming impossibility of redemption. Frankly, Rose preferred being at work with Major Gillies at the Queen’s Hospital, looking after the facial injury patients. There at least the men were getting better, and moving on, or they were dying – but at least they were not stuck on a ghastly merry-go-round of their own making, with so little idea how they got on, and no idea how to get off. Not that I know any better, Rose thought. It’s just that I can see their every mistake – the ones they’ve made and the ones they’re still making.

Peter did not go somewhere. The idea of ‘going somewhere’ dissolved with the daylight: he would not go somewhere because, it turned out, the places he might go required him not to drink at all. He seemed to think alcohol was a balanced diet – untouched trays went in and out of the study, where he sat with the blind half down, reading his Homer. Rose would stick her head in, calling him old bean, trying to tempt him out with walnut cake (they had to chase every scrap of food into him), and minding so much that he didn’t seem to mind when she treated him like a schoolboy. And equally untouched trays went up and down the stairs to Julia, who went up to bed and stayed there, ‘resting’, later and later in the mornings, longer and longer hours, the room over-warm and the curtains half open, promising that she would really try, about the getting up. Oh the curtains – Millie the housemaid trying to open them, in the interests of fresh air and health and doing as Rose had instructed her, and Julia telling her not to, and Millie, disgruntled, leaving them hanging as nobody wanted them: half open, limp, unconvincing, unconvinced. Slatternly. Millie had been a pest ever since having to come back into service, after being sacked from Elliman’s for flirting with the foreman. It wasn’t Rose’s job to hire and fire, any more than it was to look after Peter and Julia – but when a vacuum develops in a household, someone like Rose, with her strong hands and her clear eyes, cannot help but fill it.

And into this dim stuffy room Eliza would take Tom, where Julia would cry on him, and make him lie down beside her, and stroke his head, and say: ‘Oh Tom, Tom, what is to become of you?’

Was it just that socks needed pulling up? Was it some kind of shock, some nerve condition? Were they ill, or not? Dr Tayle said rest, exercise, exercise, rest, fresh air, good food, rest … Dr Tayle seemed to think if Peter could be made to walk Max every day, everything would be all right. But Peter didn’t care for Max any more, and anyway Max was always curled up on Julia’s bed, adding to the fetid smell up there of hormones and old Malmaison, and leaving silky red hairs all over the silky orange cushions. Of course Peter was unhappy, but he wasn’t wounded – the limp from his leg wound from the Somme was hardly perceptible – and he didn’t seem to be sick. There were no particular signs of shell shock – so what was it?

He needs to see a proper doctor! she thought. But he refused to see even Dr Tayle.

And anyway, Rose had her own work. Today had been particularly demanding: two skin flaps had failed, one fellow – borderline already – had had a full-on attack of hysteria, in front of the entire ward, and another had moved from what had been a small infection into life-threatening sepsis, and Major Gillies had actually shouted at Sister Black about hygiene – unimaginable! the idea that he would shout, or that Sister Black would let standards slip. While there were no new patients as such, thank God, there were still men coming through from other hospitals with badly healedfacial injuries, or badly done sew-ups or attempts at reconstruction – which were worse, because of having to tell them they need to go through it all again – or worse still, that they can’t – and the men’s disappointment … But they were getting there. If the end wasn’t in sight, at least there were no more new beginnings.

She was pushing her bicycle up the lane and into the shed, wishing that Nadine was there to talk to about it. Or Riley. She missed their good sense and their humour – it was all so bloody tragic round here! But she would hardly write to them while they were on honeymoon: ‘Sorry to tear you from your bliss; can I moan on a bit more about my cousin and his wife?’ If they think of us at all it would be to give thanks to the Lord above that they’re not still stuck here with us,she thought. They’ve escaped. They’re not really anything to us any more. Or perhaps they are. But they’re not family. They’re not responsible like I am. She realised she didn’t know what wartime friendship meant, now that war was gone. Would we even have met, without the war?

It all brought up again a question that had been bothering Rose for a while. Her big question. Should she leave Locke Hill? She’d stayed – had special permission, even, to move out from the nurses’ residence at the Queen’s Hospital – in order to help them all. Her former patient, Riley; exhausted Nadine, back from nursing in France; poor sick Julia; shattered Peter … But now that Riley and Nadine were married and gone, and order – well – order was meant to be being restored to the world, did Peter and Julia need their own house back just for themselves and Tom? Because ideas had been emerging even in reliable Rose, over the dark winter, and – not that she could think of mentioning it – she very much wanted to leave. Throughout the war she’d given her donkey work to the hospital, and her affection to Peter and Julia, Riley and Nadine, Tom. Now, her intellect was dragging its nails down the walls of her captivity, demanding its turn. Thirty-two years old, a virgin, an old maid, and likely to remain so.

In other words, free.

She pictured Riley and Nadine – or tried to – but as she had never been to the south of France she didn’t have much to go on. Their one postcard (Nadine’s writing: ‘Missing you! (well, not really!)’) showed slender palm trees along a curving road and a curving beach. It was apparently a corniche. She remembered eating cornichons once or twice in France: same shape! Someone had told her – Peter, it must have been – that the word came from ‘horn’ … She pictured Riley and Nadine on a curving beach, eating tiny gherkins, with tiny horns growing out from their foreheads through their curly black hair. They would be wet and happy from the sea, young and beautiful—

She found herself suddenly blushing. She knew perfectly well what Riley’s body looked like, from nursing him. But he was a married man, not a patient, and she was no longer his nurse.

Rose spoke to Julia about Peter. ‘I do think,’ said Rose, ‘that he might see a more … sophisticated doctor.’

‘Is he ill?’ said Julia. ‘Do you really think so?’ She perked up at the idea. Of course she would,thought Rose. Illness is something you could do something about. Illness is a reason.

‘Worth checking,’ said Rose, and, nourished by this new possibility, Julia agreed to get up after all. Rose’s constant concern was whether Peter was sticking to the new rule – Dubonnet instead of whisky, and not until six o’clock – and how one could civilly find out, without provoking a small English furore.

‘You don’t trust me, Rosie darling, do you?’ he’d say, politely, glittering, and she’d say, ‘Oh Peter, it’s not that …’

And then one morning he interrupted the regular cycle of this dull and dangerous conversation to shout at her, suddenly, ferociously: ‘Then what is it? I tell you what it is – it’s a pretty sorry state of affairs, CousinRose, if a man can’t have a glass of whisky in his own study, in his own house …’ – and Rose stood, pinioned, shocked – ‘without some bloody woman—’ And he stopped as suddenly as he had started, and cocked his head, and then turned and looked at her as if he had no idea where he was.

Rose had a secret.

She and Nadine had talked, during the winter, about how a nurse could be, when returned to her family. For Nadine, who had only been a nurse at all because of the war, who hadn’t been one for very long, who had hardly seen her wounded hero during her nursing days, and who would never be a nurse again if she could help it, the issue was how to avoid nurseyness in marriage to a physically damaged man. Nurse and patient was not a model of marriage to which she aspired, and she believed they could avoid it.

For Rose, it was quite different. Nursing was taking her in more and more. It had given her a function where she had had none, an outlet for the natural love she carried but for which she had had no object – no man, no child, no art or passion beyond her deep affection for her once-glamorous cousin Peter, with his clever brain and the sweetness he had always shown her, and his mild, elegant manners. And of course she was fond of Tom. It had turned out to be easy enough for her to be competent in caring for both of them, and Julia. Looking after people was going to be her life now. She accepted it and was looking forward to it. But not domestic. Healing, not tending. Science, not soup. She wanted more. She wanted, among other things, to know what was wrong with Peter. She had plans.

In February, Rose had received a letter from Lady Ampthill of the Voluntary Aid Detachment Committee.

Devonshire House, London W1

Dear Madam,

On behalf of the Joint Committee of the British Red Cross and the Order of St John of Jerusalem, I have the honour to ask you to fill up the enclosed ‘Scholarship Scheme Form’ if you wish to train for definite work after demobilisation. The Joint Societies have decided to give a sum of money for scholarships and training, as a tribute to the magnificent work so generously given by VAD Members during the War.

Training will be given for those professions for which the work done by members would make them particularly suitable, such as the Health Services or Domestic Science. A preliminary list is appended, with the approximate period of training and probable salary to be gained when fully trained.

A limited number of scholarships to cover the fee and cost of living will be given to those who pass the qualifying examinations with special proficiency, but in other cases it is hoped to assist materially those members who wish to be trained for their various professions in centres all over the country.

The work of VAD Members is beyond all praise, and we very much hope that they will again be leaders in important patriotic work, which equally demands the best of British womanhood.

Yours faithfully

MARGARET AMPTHILL

Chairman, Joint Women’s VAD Committee.

Rose read it carefully. A woman – Lady Ampthill – was writing to her, a woman, offering money, training and support. She read the final sentence three times: the words leader, important, best, work, and womanhood in the same sentence. This, Rose thought, was the most beautiful letter she had ever received. (Not the most beautiful she had ever read – those were Nadine’s letters to Riley while he was in hospital, which Rose had had to read to him – my gosh, they had been something.)But no – this was about a future in which she could see herself. This was like Madame Curie setting up x-ray labs in the Belgian field hospitals, and fixing the wiring while she was at it, and rigging up field telephones. This was potentially …

There would be a catch.

She didn’t want to study domestic science! But health services? What did that cover?

The list of requirements was enclosed. Breathing steadily, Rose unfolded it and sat down to read it.

1 1) Length of Service. – Members must have worked officially in a recognised British Unit prior to January 1917, and have continued working until their services were no longer required. Well, that’s all right.

2 2) Recommendations. – Applications for Scholarships must be forwarded with a recommendation from: (a) The Matron … … … For Nursing Members working in Military Hospitals. Well that should be all right too. They will probably be sad to see me go. I think.

3 3) A new Medical Certificate will be necessary. Again, all right.

4 4) Age Limit. – 20–40. Unfair on the older ladies. But all right.

5 5) Standard of Education. – Certain Scholarships will require a high and definite standard of education, which will be taken into consideration. Ah. High and definite. That could mean anything. Will my plain old girl’s education count? Or will they want a degree or something?

6 6) Applications. – Applications should be made before 31 March 1919.

7 7) Further Correspondence. – When a form has been filled up by a Candidate, forwarded by her Officers, and approved, further correspondence will be carried on confidentially with the Member with regard to the amount of financial assistance required and other matters.

And on the other side was the nub of it: ‘Scholarships may be awarded for the following types of work …’

First on the list: ‘Medicine’.