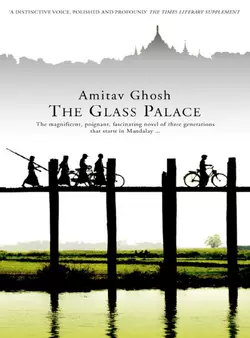

The Glass Palace

Amitav Ghosh

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 709.41 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A sweeping story of Burma and Malaya over a span of one hundred years that has rightly become a modern classic no for the first time in ebook. From the Man Booker Prize shortlisted author of Sea of Poppies.Rajkumar is only another boy, helping on a market stall in the dusty square outside the royal palace, when the British force the Burmese king, queen and all the court into exile. He is rescued by the far-seeing Chinese merchant, and with him builds up a logging business in upper Burma. But haunted by his vision of the royal family, he journeys to the obscure town in India where they have been exiled.The picture of the tension between the Burmese, the Indian and the British, is excellent. Among the great range of characters are one of the court ladies, Miss Dolly, whom he marries; and the redoubtable Jonakin, part of the British-educated Indian colony, who with her husband has been put in charge of the Burmese exiled court.The story follows the fortunes – rubber estates in Malaya, businesses in Singapore, estates in Burma – which Rajkumar, with his Chinese, British and Burmese relations, friends and associates, builds up – from 1870 through World War II to the scattering of the extended family to New York and Thailand, London and Hong Kong in the post-war years.